By Grant Keddie (June 11, 2020)

The properties on which our legislative buildings are now located in Victoria Harbour are within the traditional territory of the Lekwungen First Nations, today represented by the Esquimalt and Songhees Nations. There is clear evidence in the form of written documents and maps that James Douglas intended this property to become an Indigenous Reserve as part of the treaty settlements of 1850. (See Appendix 1: The Paper Reserve.)

The legislative property is shown on this 1862 map to the left of lot VI belonging to James Douglas. It is located at the southern foot of the James Bay Bridge. (BC Archives 11520A. Part of Beckley Farm No.4.)

The Lekwungen people were rightfully compensated, in November of 2006, with an out of court settlement for the failure of this property to become a modern First Nations reserve. There is no evidence of any agreement being made in the nineteenth century to dispose of this proposed reserve with any Lekwungen peoples.

This is a case where, in my opinion, compensation would not need to be predicated on the Lekwungen ever having a village on the property. There is, in fact, no archaeological evidence that there was a pre-contact village on this property. (See Appendix 2: Archaeological Observations in the Legislative Building Precinct and Along the Adjacent Waterfront 1972–2019. )

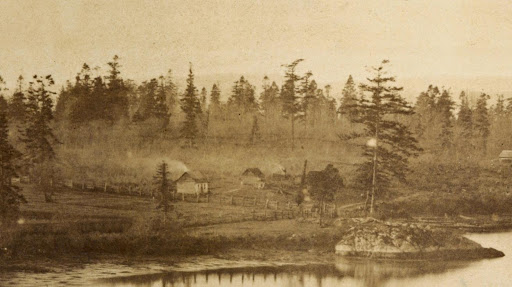

Homestead of Montreuil on what became the legislative Grounds, 1858. Buildings owned by non-Indigenous peoples seen to the right of this image on the larger panorama are west of the legislative property. Courtesy of the American Library of Congress. #2005680426, No.2.

A Historic Overview of the Legislative Property

Here I will examine the nature of some of the early historic documentation regarding the legislative property.

There are no Hudson Bay company records or accounts of military, religious or other visitors to Victoria Harbour in the 1840s to early 1850s that pertain to Lekwungen people living in a village at the location intended to be a future “Indian Reserve” shown on the 1854 map The historic Inner Harbour village was located a few blocks further west, near Laurel Point. This village was one that was co-occupied by local Xwsepsum treaty people and their Clallam relatives from the American side of the Straits of Juan de Fuca for a short period of time about 1847–1855.

I would propose that the historic village sometimes being referred to as being “near”, “in front of” or “on” the legislative property was in fact at the latter location, near Laurel Point. (See Appendix 3: The Location of the Historic Village of the Xwsepsum and Klallum.)

Here I will present some observations in regard to the earlier use of the property around the legislative buildings. There is no archaeological evidence of a shellmidden that would represent the remains of a village site at this location. Direct accounts that observe local First Nations occupying this site area are lacking.

Dorothy Kennedy has provided a detailed analysis of the ethnographic literature pertaining to the locations in Victoria Harbour and the Gorge Waterway of the Kosampson and other Lekwungen peoples (Kennedy 2006:57-64 & 70-86). I refer to this and add my own opinions in Appendix 4: Lekwungen Winter Villages and Seasonal Movements.

Historic Observations: Who Occupied Buildings on the Legislative Property?

An 1851 map (HBCA G.1/131 [N8362]) of surveyor Joseph Pemberton includes the area that was to become the legislative precinct. On this map are five small buildings marked in red. One small square dwelling in red is located near the northwest corner of James Douglas’s property, and four more small square dwellings marked in red are in a line continuing on the property to the west along the waterfront—which later became the location of the Parliament buildings.

Portion of Pemberton Map showing the legislative precinct area (G.1/131 [N8362]). All houses are coloured in red.

These buildings only appear together on this one map. The map was most likely created from information collected by surveys undertaken in the late spring to early summer of 1851. The one building on Douglas’s property is also located on a map dating 1852 from information collected in the late fall of 1851. These small buildings were most likely occupied by Indigenous and/or non-Indigenous persons working for James Douglas during a period of intense building on his property between late 1850 and the summer of 1851.

In regard to the James Bay “Indian Reserve”, William Tolmie’s letter to Thomas Fraser of June 24, 1865 states: “That the piece of Land in question was ever in any sense an Indian reserve has from the first – been disputed by the company’s Officers, resident here, since the foundation of the Colony. – Indians of various Tribes sometimes employed by the Governor, and on other occasions by the Company, were allowed to reside on it at times under the surveillance of a half-breed (Montreuil) who lived on the spot in a small cottage said by Tiedmann to have been claimed by the Governor and to have been, with another small house on this Reserve, by him transferred to the Colony in 1859 for the sum of $200.” (Tolmie, William J. Letter of June 24th, 1865; HBCA A.11/80 f.148-169d)

The James Douglas Property

On January 13, 1849, a Charter of Grant awarded Vancouver Island to the Hudson’s Bay Company for “the advancement of colonization and encouragement of trade and commerce”. The main condition was to establish “a settlement or settlements of resident colonists” by 1854. Revenues from land sales were to go mostly for the construction of public schools, buildings, roads and bridges.

Douglas and other Hudson’s Bay company employees now had the opportunity to acquire land that had previously been denied to them, as the purchase was seen as being in conflict with company business.

On December 10, 1849, James Douglas applied to Archibald Barclay to acquire land for himself. He showed the letter of application that month to Eden Colvile. He wrote to Hargrave on January 17, 1850: “I am thinking of making a purchase of land on Vancouver’s Island…more as a speculation than with any serious intentions of settling. Yet there is no saying what in the chapter of accidents may come to pass.” (Letter to Archibald Barclay, Secretary to the H.B. Co. Governor and Committee. Eden Colville’s Letters. 1849-52. The Publications of the Hudson’s Bay Record Society XIX. Edited by E.E. Rich, 1956). Douglas was unhappy with the small dividend from the HBC and seemed to consider quitting his job. He said to A.C. Anderson on October 28, 1850: “I hope the next [dividend] will be more respectable – or the sooner we cut and run the better.” (Fort Victoria, Correspondence Outward, 1850-1858, PABC)

According to Roderick Finlayson, it was Douglas who convinced the governor and committee of the HBC to open the fur trade reserve for public sale, with the exception of 1212 acres containing part of downtown Victoria and Beckley Farm. (Finlayson, Autobiography of Roderick Finlayson, ms, PABC; Rich, The Hudson’s Bay Company, vol. 3:763)

Douglas acquired his property indenture on Dec. 15, 1851. (Map – Victoria District, Lot No. 1, Section VI, James Bay by Joseph Despard Pemberton, 1851, HBC Archives H.1/1 fo.4) In late 1850 Douglas also applied to acquire what became the 300 acre estate called Fairfield. (Victoria District. Section 1, Lot no.2, HBCA H.1/1 folio 6)

Building Activity

On September 1 of 1850, James Douglas was—on his own property—in the process of “putting up a dwelling House with the aid of three of the Company’s servants, whose board and wages will be charged to my private account, for the time I employ them, and a party of native labourers, who promise to become useful as rough carpenters.” Douglas also acquired his 10 acres at Rosebank in Esquimalt harbour at this time. (Douglas to Barclay, Fort Victoria Letters, p. 115)

Douglas had the foundation of his house finished in January of 1851. On January 23, he wrote Hargrave: “I have lately purchased a bit of land in this neighbourhood…and have laid the foundation of the first private house in the town of Victoria. This will of course cost me a good deal of money, but then it will be a refuge in time of need, and eventually repay the original outlay with interest.” (Hargrave papers, NAC). On July 1, 1851 Rear Admiral and Commander-in-Chief Fairfax Moresby reported to the Secretary of the Admiralty that “Douglas has a commodious dwelling, nearly completed, on his farm, near the Fort, and a farm house on the inland limit.” (BC Archives GR332, Vol. 1:335-41)

By April of the same year, while his own 10 acres were “under improvement” (Douglas to Barkley, Victoria Letters, p. 176), Douglas started a vigorous building program on the HBC company property. He employed “100 Indians” in clearing brush and trees and began “putting up buildings about the Fort, having a dwelling House, and a Flour Mill in progress,” erecting a hospital and having plans to erect buildings “for religious and educational purposes.” (Letter of April 16, Douglas to Barkley, Fort Victoria Letters, pp. 170-172).

The five houses on Pemberton’s 1851 (G.1/131; N8362) map (one on and four west of the Douglas property) would have been placed on the map by Pemberton during the spring to early summer of 1851 by which time he had finished most of the Victoria harbour area work. On August 5, 1851, Douglas reported to Archibald Barclay that “Mr. Pemberton is actively employed, in the survey of the Fur trade Reserve, and the Victoria District generally. The day after tomorrow he will proceed toward Esquimalt.…He expects to complete the Victoria District in about 3 weeks hence, when he will forward a pretty complete sketch.” (Fort Victoria Letters 1846-1851. Publications of Hudson’s Bay Record Society XXXII, Editor Hartwell Bowsfield, Hudson’s Bay record Society, 1979, p.206) Pemberton’s report, dated September 11, was sent by Douglas with an accompanying map on October 6, 1851 (Bowsfield 1979:218).

The original map could not be located in the HBC archives (see Bowsfield 1979, footnote 2, p. 218). Ruggles, in his detailed study of all the Hudson’s bay Company maps, concludes that a map in the Land Title & Survey Authority of British Columbia “is likely the original manuscript topographic map.” This map, titled “Victoria District & Part of Esquimalt,” is located in Maps and Plans Vault L, Locker 5, given numbers 108577 and 108578. The map does not show houses on the property west of the Douglas Property.

Ruggles considers the Pemberton 1851 map—“Victoria & Puget Sound Districts Sheet No.1, HBC map G.1/131, N8362 (that shows the above mentioned buildings marked in red)—and two others (G.1/132 & G.1/133) to be “tracings or copies” of this original. (Ruggles, Richard I. A Country so Interesting: The Hudson’s Bay Company and Two Centuries of Mapping, 1670-1870. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1991, pp. 100; footnote 12, p. 284)

If G.1/131 is a tracing of the original, it would appear that the one square building structure on the Douglas property and the four structures on the adjacent property were added from information collected in the spring or early summer of 1851. Four of the houses are gone by the end of 1851. Pemberton’s 1852 map (HBCA G1/258a) shows only one red square on Douglas’s property and none on the adjacent property to the west.

By the end of 1851 when Douglas’s house was nearly complete these five houses appear to have been gone – and therefore not marked by Pemberton’s detailed 1852 map of the local area. (A Plan of the town of Victoria Shewing Proposed Improvements, HBCA Map Collection, G.2/38 [T13107] Hudson’s Bay Company Archives Provincial Archives of Manitoba)

The ground survey for the 1852 town of Victoria map would have been started in the late fall of 1851. Douglas reports to Barclay on December 9 of 1851 that Pemberton is “now completing the survey and preparing a plan of the town site of Victoria.” (Bowsfield p. 239)

The row of five buildings marked in red are not shown on any maps predating 1851. They are not marked on the 1850 “Map of the Victoria District, Vancouver’s Island” by Walter Colquhoun Grant (HBC Archives Map Collection, G.1/256) or on any of the earlier Admiralty Surveys of the Victoria Harbour area.

It was noted on September 11,1855, that “Mr. Douglas has built a house and taken 20 acres of land in the most desirable spot and has reserved for purchase 200 acres more adjoining it.” (H.W. Bruce [at sea on HMS Monarch] to Ralph Osborne, GR332, Vol. 2: 248.)

Much later, Edgar Fawcett, in his reminiscences (1912:86-87), observed:

“Before the road opposite the Government grounds, which is now Belleville Street, was reclaimed from the sea, [*this was only the area of the slight bay near the N.E. corner of the legislature grounds] there was an Indian trail which ran through the woods, From Laing’s Ways, [*today known as Fisherman’s Wharf area] in the direction of town along the water-front, around the head of the bay to Humboldt Street. I might say that the plat [*plot] of ground on which the Government buildings were built in 1859 was bought from a French-Canadian who came overland form Montreal, and although in the service of the Hudson’s Bay company for years either could not or would not speak a word of English other than ‘yes’ and ‘no’. He built his house here and lived here until he sold out to the Government, the house being afterwards used as a Government tool house.

Mr. Harry Glide, from whom I got these particulars, is a pioneer of 1856, and lived near the outer wharf. He married a daughter of Mr. Laing. He says all James Bay from the bridge to the mouth of the harbour was covered with pine trees, [this would be true of the southern half of what is now the community of James Bay, where the dominant species was Douglas fir. Garry Oak communities and open parklands and swampy areas existed to the north] and all this land, together with that facing Dallas Road up to Beacon Hill, was called Beckly Farm. The greater part of all these trees were cut down for Kavaunah [*died in Victoria on November 21, 1891 at age 60. Registration number 1891-09-007565], a man whom many will remember as having a woodyard about where the James Bay Athletic Association now stands.” (*See B.C. Archives G-02827 and C-09028)

Appendix 1

On August 26, 1854, James Douglas sent a letter to Archibald Barclay of the Hudson’s Bay Company:

“I herewith transmit a letter from Mr. Pemberton, with a tracing of an Indian Reserve, which has been accidentally omitted in Lot No. 24, Section XVIII, though reserved to them, on the general sale of their lands; they have since offered it to me for sale, but as the cost may be considerable, and I do not want the land for my own use, I declined their offer though I should have no objections to purchase it in part, if the company will take the remainder of the lot. I will probably make some arrangement with the Indians if they dispose of it, on reasonable terms, particularly if any other party should be tampering for the purchase of their rights.”

Although the treaty of 1850 for this area was made with the Swengwhung family of the Lekwungen people, there is no mention by Douglas of which Indigenous peoples he talked to regarding the land. But we can conclude that it was obviously “reserved” for some or all Lekwungen people “on the general sale of their lands.” (Douglas to Barclay A/C/20/Vi2A, P. 222)

Appendix 2

Archaeological Observations in the Legislative Building Precinct and Along the Adjacent Waterfront 1972–2019

For 48 years, my office windows at the Royal BC Museum overlooked the legislative precinct. In examining the question of whether there was once a village or season camp site on the location of the present legislative buildings, I have, over this period of 48 years, observed and examined numerous trenches and holes being dug on and all around the Legislative property.

This has included such activities as water, sewer and gas pipe installation and repair along Belleville, Government and Menzies Streets; the excavations in the repair and rebuilding of the sidewalk and walls along the waterfront on the north side of Belleville in front of the legislative grounds; the installing of the underground sprinkler system in the legislative lawns; and underground repairs related to the driveway, sidewalks, fountain and War Memorial on the legislative property. I also observed many smaller hole excavations involving tree removal and planting and the installation of the totem pole.

I have looked carefully for any evidence that the location was once the site of a village or seasonal camp site, as I have done in many other parts of the city. Archaeological shellmiddens are common on bays and inlets in greater Victoria. These locations always have some evidence of discarded shellfish remains, fire-altered rocks, bones, charcoal rich soil and other materials. Even where serious damage has occurred to many shellmiddens around Victoria there is always evidence of fragmentary scattered remains. None of this material evidence has ever been observed around the Legislative precinct. I can only conclude that this location was never occupied as a village or seasonal camp site.

The fact that the area near the old shoreline along Belleville Street was built up with soil rather than having soil removed would make it more likely than shellmidden material from any old village site should be easier to find in modern excavations in the area. When the original legislative buildings were constructed and Belleville Street was being constructed, a wooden wall (see photograph) was built at the edge of the bank and large amounts of fill brought for the road construction.

The location of the legislative buildings would not be a favourable location for a village site, as it lies on what was once (and still is in some locations) a very rocky shoreline, not conducive to the easy in-and-out movement of canoes. Exceptions are locations that could serve as defensive locations, these being best placed on a high peninsula that can be fortified from enemy attack and from which one can see enemies approaching.

The three known ancient sites in Victoria’s Inner Harbour, which starts at Shoal Point, are all on steeper rock bluffs. One of these, DcRu-123, located at Lime Point on the north side of the harbour, is a known defensive site that once had a trench embankment across its back end. The others, DcRu-33 and DcRu-116 are located on Raymurs Point near Fisherman’s Wharf and on the bedrock bluffs around the Capital Iron building near the intersection of Store and Chatham Streets.

Further, there are no water sources on the legislative property. Villages are usually adjacent to a freshwater stream.

Excavations around the Steamship building From March 14, 2017, to February 18, 2018.

Keddie photographs.

Excavations along the south side of the Blackball Ferry terminal, February 2016.

Keddie photographs.

Excavations along shoreline, February 2016 to June 2018.

Keddie photographs.

Excavations along Government Street and near Belleville Street.

Keddie photographs.

Excavation of legislative grounds driveway.

Keddie photographs.

Appendix 3

The Location of the Historic Village of the Xwsepsum and Klallam

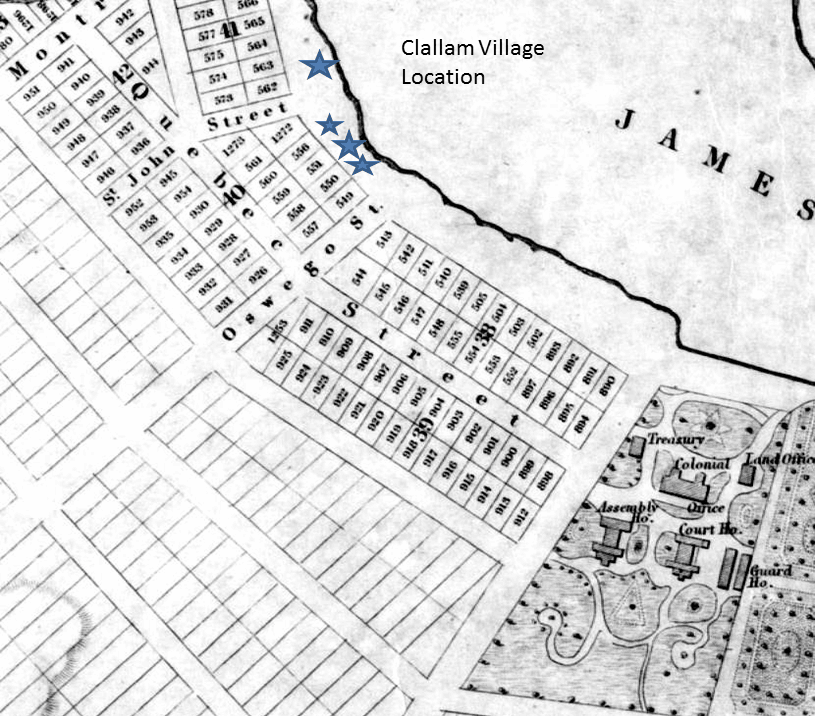

James Teit, working with Klallam Nation consultants of Washington State in 1907-10, was told there was “a village of them formerly in Victoria” and that “they were closely related to the Songhish” (Teit 1910). Henry Charles, the Beecher Bay Klallam consultant of anthropologist Wayne Suttles, told him in the 1950s that “Scaqe’nam, a chief from Port Angeles, moved over to Victoria when the whites came, in order to make shingles and plant potatoes for them.” (Suttles 1974:11) This community would be the “Clallam Village” referred to by the editor of the Weekly Victoria Gazette on August 28, 1858. It was located in the community of James Bay, west of the legislative buildings and just to the east of Laurel Point. It was occupied about 1847 to 1855.

Laurel Point was half its current width in the nineteenth century. The location of the historic Xwsepsum/Klallam village is on the far upper left to the east of Laurel Point. Songhees Point is at the centre in the foreground and was once part of the Old Songhees Reserve. Grant Keddie photograph.

This village included Klallam people from the Olympic Peninsula, and some of the Sapsom or Kosampson (Xwesepsum) people of the 1850 Douglas Treaties. The Klallam may have lived here by right of intermarriage with the Xwesepsum, or, after the Klallam moved here from the Port Angeles area, the Xwesepsum may have joined them at the locality from a village in Esquimalt harbour. This was a short-term historic village. There is no evidence of a village site being here before the late 1840s. There were no occupied village sites observed in Victoria’s Inner Harbour until after the building of Fort Victoria in 1843. For further information on the context of this article see Keddie (2003).

In 1905, anthropologist Charles Hill-Tout collected information from Lekwungen people (the Songhees and Esquimalt of the Victoria region) who lived on or had close family ties to the Esquimalt Reserve located in Esquimalt Harbour. Hill-Tout’s interpretation of the information indicated that James Douglas had “also transplanted the village of the Qsapsem [Kosampson], who dwelt near the spot where the Parliament Buildings now stand.”

One of the people that Hill-Tout received his information from was “the wife of Tom James.” She was called Sitlamitza, or Mary Anne James. She was a part of at least one family of Xwesepsum people that lived in the “Clallam” village on the shore to the west of the legislative buildings. Sitlamitza was born in this village around 1847 to 1850. But as she left when only one or two years old, she would not have any personal memory of this location. She would have had the place of her birth explained to her by others, years later.

In 1912, William Roberts, a Songhees Band councillor, stated that Mary Anne James “belongs to Saanich Arm [Upper Gorge] and is of the Sapsam [Xwesepsum] tribe, which is not Songhees” [i.e., not among the people that made up the Songhees Reserve]. A response came from Reverend C. M. Tate, who had worked among the Lekwungen since 1873, and was an advocate for the James family who went to his church:

“The home of the Sapsams was Victoria harbor, and their village stood in front of where the parliament buildings now stand. The home of the Songhees was at Albert Head, from which place they moved to Victoria harbor when the Hudson’s Bay Company built their fort.” This is a very oversimplified version of Lekwungen history (see Duff 1969).

A notarized statement by Mary Anne James was dated January 10, 1912. It is not know who assisted her in writing this, but it was likely Reverend Tate. It stated in part:

“That my Indian name is Sitlamitza. That I was born in my father’s house in front of where the present parliament buildings now stand. That my mother died in giving birth to me, and my father was killed when I was a baby. That my uncle, Chief Seesinak [“Say-sinaka” was the 5th person on the Kosampson treaty list of 1850; his grandson Joe Sinopen, born 1863, and his son Edward Joe, born 1885, were both former chiefs of the Esquimalt band], adopted me. That when Sir James Douglas moved the Indians to the reserve across the bay, my uncle asked for a place at Esquimalt. That my younger days were spent between Victoria, with my aunt, Seesinak’s sister, and Esquimalt.”

It is uncertain if this comment about the movement “to the reserve across the bay” refers to the 1844 movement of peoples camped in the Johnson Street Ravine area or that some of the people living in the historic village near Laurel Point moved across to the Old Songhees Reserve. If it does refer to the former, James Douglas did not move the Songhees to the Old Songhees Reserve, as he did not take charge of the Fort until he moved here in 1849. Roderick Finlayson was the person who arranged for some of the Songhees to move to the west side of Victoria Harbour from their temporary camps.

Mary Anne James indicates that she later lived on both the Old Songhees Reserve in Victoria harbour and the Esquimalt Reserve in Esquimalt Harbour. It is likely that Mary Anne’s mother’s family, father’s family, or both, originally came from Esquimalt harbour to join the Klallam village after the founding of Fort Victoria. This may have been a result of previous marriage relations with the Klallam: Mary Anne’s nephew Chief Edward Joe of the Esquimalt Reserve had a grandfather named Skekanim who was from Port Angeles. Later, when treaty negotiations began in 1850, Mary Anne’s uncle “Say-sinaka” may have asked at that time for a reserve in one of their old Xwesepsum village sites back in Esquimalt harbour. It is likely that the family had maintained a seasonal occupation of the upper Esquimalt Harbour area during their stay at the “Klallam” village or stayed with relatives who continued to live there.

Hill-Tout himself says that before the fort was built, the Xwesepsum lived “on the Gorge.” James Deans, who came to the Craigflower area in 1852, was told that their village was on the Gorge at what is now Kosampson Park.

Outlines of the location of four houses at the site of the Klallam/Xwesepsum village can be seen in Figure 3. The map shows new surveyed lots several blocks west of the 10 acre “Indian Reserve” land that was to become the site of the Legislative buildings. The map shows four elongated houses with lot boundaries cutting through two of them, suggesting they were abandoned by this time. Three houses span Lots 513-15, and one house spans lots 516-17. This location today is along the waterfront in the area of Oswego and Pendray Streets at the S.E. corner of Laurel Point.

The Klallam village was located “near” the parliament buildings, according to Charles Hill-Tout. It appears that Reverend Tate changed the story to “in front of” the legislative buildings.

The subject of which Lekwungen families occupied the area around Victoria Harbour and whether there was a village at the site of the legislative buildings is a subject of debate (see Kennedy and Bouchard 2006:57-64).

Appendix 4

Lekwungen Winter Villages and Seasonal Movements

Songhees band members Jimmy Fraser, Sophie Misheal and Ned Williams identified Swengwhung as the people who formerly lived along the Gorge above the Tillicum Road Bridge (Duff 1969:35). This group had houses at the bay inside Gorge-Kinsmen Park. This is the known location of a shellmidden, archaeological site DcRu-5. Jimmy Fraser noted that one woman remained alive whose mother had lived in this village. If the living women was about 80 years old in 1950, we can speculate that there was at least one house that her mother lived in at this location before about 1870. Fraser indicated that most houses were located just west of the bridge at locations recorded as archaeological shellmidden sites DcRu-112 and DcRu-7. The former contains only a light scatter or shellmidden and was likely only occupied for a short time. The latter is a large shellmidden dating back at least 1,500 years based on the artifacts found there and radiocarbon dating (around 1,000 years).

Edward Joe of Esquimalt, and his father Chief Joe Sinopen before him, considered the Swengwhung peoples to be part of the general migration of Songhees into the Inner Harbour after the founding of Fort Victoria (Duff 1996:35; Hill-Tout 1907:307). Edward Joe said that the Xwesepsum owned the entire Gorge and Inner Harbour (Duff 1969:35).

Hill-Tout recorded that the Xwesepsum village before the time of the fort was on the Gorge. This was located at Kosampson Park at the location of the old Criagflower school house. This is a large shellmidden recorded as archaeological site DcRu-4. James Deans also noted that the Esquimalt came from this location in the not-too-distant past (Macfie, 1865).

Anthropologist Dorothy Kennedy pointed out that Suttles discussions with Cecelia Joe at the Esquimalt Indian Reserve in 1952 had raised the idea that some of Hill-Tout’s villages might not be winter villages, but rather sites that were occupied at other seasons, a practice common among the Coast Salish. (Kennedy 2006:31). Kennedy indicates that

“The ethnographic literature presents several scenarios of how Lekwungen local groups may have occupied southern Vancouver Island. According to Cecelia Joe, …the Lekwungen winter villages were all situated around Victoria Harbour. This included the sc̉áηcs people, otherwise found near Albert Head, and certainly the village of Mrs. Joe’s husband’s people, the Kosapsum (the “Kosampsom” of the 1850 treaty), who reportedly spent the winter where the Parliament Buildings now stands, and according to Mrs. Joe, owned the Gorge and Esquimalt Harbour. Mrs. Joe also reported that the Lekwungen people of Cadboro Bay had a winter location at Parson’s Bridge, in Esquimalt Harbour, and that the Discovery Island people had a winter site at Rose Bank (inside Dunns Nook on Esquimalt Harbour’s west shore). …Still, in the winter, according to Cecelia Joe, the Lekwungen could be found in Victoria Harbour where, out of the wind, they built dance houses for their winter ceremonials and, in nice weather, fished the winter runs of spring salmon found offshore.” (Kennedy 2006:32)

Not all Lekwungen consultants agreed with Cecelia Joe’s designation of Victoria Harbour as the Lekwungen’s winter quarters. David Latess (also spelled Latesse, who was of Lekwungen ancestry) told anthropologist Diamond Jenness that the old summer home of the main body of the Songhees was at Xthapsin [xwsέpscm, anglicised as “Kosapsum” or “Kosampsom”], just above the Gorge, and that their winter home was at Cadboro Bay. While it is unclear what is meant by the main body of the tribe, Latesse’s account clearly recognizes that the same people (the Songhees) used both a site on the Gorge and in Cadboro Bay, areas sometimes named in association with specific Lekwungen local groups, …Moreover, Sophie Misheal and Ned Williams divided the Gorge, not Victoria’s inner harbour, into sites occupied by distinct local groups, noting with respect to the “lck’wcŋcn” they come in here during winter, with reference to the area from Gorge Bridge to Songhees Point, while the Swengwhung and Kosapsum people, according to them, wintered at sites farther up the Gorge. Though the notes are cryptic, they do indicate more movement within the Lekwungen territory than reflected by the rigid divisions of land ownership set out in the treaties. These above-noted aboriginal elders offered different perspectives on the season of occupation and the precise local group’s association with sites located on the protected waters – Victoria and Esquimalt harbours and the Gorge—yet there was a recognition that named groups of people used a variety of sites associated with the general Lekwungen territory”. (Kennedy 2006:33)

Wilson Duff, based on his interviews with these Songhees Band members, along with accounts he received from Edward and Cecelia Joe of Esquimalt, suggested that both the Xwesepsum and Swengwhung groups formerly wintered up the Gorge, and that both groups were living in the Inner Harbour area at the time of the treaties in 1850, the Xwesepsum likely on the James Bay Reserve site and the Swengwhung at the new Songhees Point village across from the fort. (Kennedy 2006:35)

My opinion would be that Cecelia Joe, who had no personal experience on the Old Songhees, could have been making reference to the early historic activities on the Old Songhees first occupied in 1844 and these activities did not pertain to pre-contact practices. An alternate explanation could be confusion regarding the perception of the term “Victoria Harbour,” which may have included what today we call the Gorge Waterway. The winter villages referred to by Cecelia Joe were likely further up the Gorge waterway, which was included in the term “Victoria Harbour”.

References

Bowsfield, Hartwell (ed). 1979. Fort Victoria Letters 1846-1851. Publications of Hudson’s Bay Record Society XXXII, Hudson’s Bay record Society, 1979, p.206).

Douglas to Barclay. Royal B.C. Museum Archives A/C/20/Vi2A, P. 222

Fawcett, Edgar. 1912. Some Reminiscences of Old Victoria. Toronto. William Brigs.

Finlayson, Roderick. (c.1891). Autobiography of Roderick Finlayson, ms, PABC.

Hill-Tout, Charles. 1907. Report on the ethnology of the southeastern tribes of Vancouver Island, British Columbia. Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. vol. 37: 306-374.

Keddie, Grant. 2003. Songhees Pictorial. A History of the Songhees People as seen by Outsiders, 1790-1912. Royal B.C. Museum, Victoria.

Kennedy, Dorothy. 2006. ABORIGINAL AFFILIATION OF THE JAMES BAY RESERVE. Final Report. Prepared for: Greg McDade, Q.C., Ratcliff & Co. North Vancouver, BC. Counsel for the Esquimalt and Songhees First Nations. Prepared by: Dorothy Kennedy, M.A., D.Phil. Bouchard & Kennedy Research Consultants. Victoria, BC, April 17th, 2006.

Kennedy, Dorothy and Randy Bouchard. 1995. An Examination of Esquimalt History and Territory: A Discussion Paper. Prepared for: the Esquimalt Nation. B.C. Indian Language Project, Victoria, B.C., July 29th, 1995.

Rich, E.E. (ed) 1956. Letter to Archibald Barclay, Secretary to the H.B. Co. Governor and Committee. Eden Colville’s Letters. 1849-52. The Publications of the Hudson’s Bay Record Society XIX.

Rich, E.E. 1960. The Hudson’s Bay Company 1670-1870. McCllelland and Stewart, Toronto, Vol. 3:763.

Ruggles, Richard I. 1991. A Country So Interesting: The Hudson’s Bay Company and Two Centuries of Mapping, 1670-1870. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Suttles, Wayne. 1974. Coast Salish and Western Washington Indians 1. The Economic Life of the Coast Salish of Haro and Rosario Straits. Garland Publishing Inc. New York.

Teit, James A. 1910. Salish Tribal Names and Distribution. June 10, 1910. Unpublished Manuscript in the Files of Franz Boas. American Philisophical Library. (Film 372, Roll 15) [RBCM Archives Additional Manuscript 1425, Reel A 246].

Tolmie, William J. Letter of June 24, 1865; HBCA A.11/80 f.148-169d.