By Grant Keddie

Preface

One of the great tragedies in the History of British Columbia was the smallpox epidemic of 1862-63, which killed thousands of Indigenous peoples. A previous pandemic spreading across northern North America from the western Atlantic coast hit British Columbia around 1780, before non-Indigenous settlement in the region. Estimates from other documented areas would suggest that at least 80% of the population may have died from this first introduction of smallpox into the region. This massive interruption would have resulted in the re-alignment of Indigenous societies.

In early 1853, a smallpox epidemic spread from the Columbia River to Neah Bay on the Olympic Peninsula of Washington State, causing a heavy death toll in that area. George Gibbs reports in 1854, that the Makah of the Cape Flattery region were reduced from 550 to only 150 people (Gibbs 1855).

On May 16, 1853, James Douglas wrote to Archibald Barclay, the secretary of the Hudson’s Bay Company: “the small-pox is said to be raging among the Indian tribes on the American side, about Cape Flattery, but it has not made its appearance in this part of the country: and as a precaution against the ravages of that fatal disease, the Indians residing with the Colony, have been generally vaccinated”. This statement is reinforced by W. E. Cormack who stated on October 21, 1862: “the practice of vaccination was widely introduced among the natives by the Officers of the Hudson’s Bay Company many years ago” (Anderson 1878).

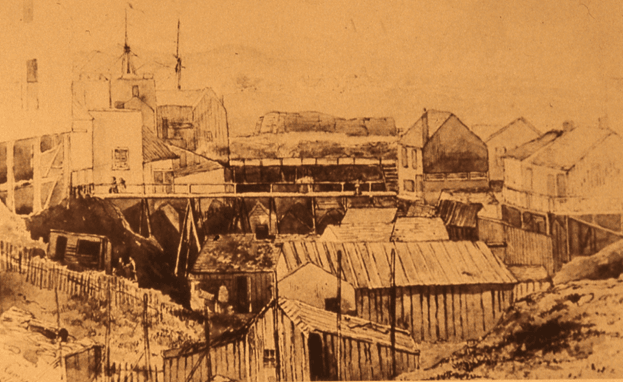

Figure 1. The Songhees Village in Victoria Harbour in 1857. James Alden drawing. RBCM6811.

The Victoria Smallpox Epidemic of 1862.

The events of the Victoria smallpox epidemic of 1862 are complex, but the conspiracy theories that have promoted the idea that the smallpox spread was a highly organized plot to commit genocide against Indigenous people finds no support in the events of the disease in Victoria. This, of course, should not detract from the fact that colonialism was a process of eliminating Indigenous culture.

There are thousands of Indigenous people alive today because of getting inoculated by Dr. John Helmcken and others. The Songhees that were inoculated in Victoria did not get the disease. To understand how one needs to judge and interpret what is documented about the Victoria smallpox at the time of the epidemic, it is necessary to understand the local politics, the movements of people and the characteristics of the disease itself.

The Political Context

When we examine history we need to judge people in the context of the prejudges of their time. We need to observe not just what they said but the actions they undertook. As historian Cole Harris has pointed out: “Colonialism is made up of many different people and stories that are not unrelated, but are also not one amorphous ‘colonising force’ either “ (Harris 2004:179).

We can look at just macro-histories which tend to lose important detail or just micro-histories which can fail to see the larger context. The time of the smallpox was a transition between the fur trade period and the very early colonial period. The mainland Colony of British Columbia at the time of the epidemic was less than four years old and sparsely occupied by non-indigenous people.

Historian Robin Fisher has shown the clear distinction between the short period that Douglas and his supporters were part of government and the substantial changes in non-humanitarian government practices toward indigenous peoples instigated by individuals in 1864: “a year of change in the administration of the colony of British Colombia; James Douglas retired from the Governorship and Joseph Trutch was appointed Chief Commissioner of Lands and works” (see Fisher 1981). For a detailed discussion of the beliefs of James Douglas, see Spitz (2018).

The livelihood of the Hudson’s Bay Company personnel depended on Indigenous people bringing in furs and food, and providing a source of inexpensive labour for their activities. Many of the company personnel were married to Indigenous women. Men like James Douglas, John Helmcken and Joseph McKay, during their short period in government, were strong defenders of Indigenous rights, struggling against an opposition that did not believe in providing any rights. John Helmcken was responsible for saving hundreds of lives by vaccinating Indigenous people. He is reported at the time to have vaccinated 500 Indigenous people within the first six weeks of the smallpox out-break, starting with the Songhees chief and his family.

Figure 2. Cecila Helmcken the Indigenous wife of Dr. John Helmcken. Cecila’s daughter “Dolly” was born during the smallpox epidemic on June 24, 1862. PDP02635_141.

The situation in Victoria leading up to the epidemic was the continual coming and going of many hundreds of indigenous peoples from Washington State, central Vancouver Island to Haida Gwaii and the northern coast into Alaska. Some of these were traditional enemies who were killing each other on a regular basis in Victoria. Many Indigenous peoples lived in the city while working for non-Indigenous employers.

A significant factor in the number of smallpox deaths was the refusal to vaccinate. As Alexander Garrett observed at the time he worked with northern indigenous smallpox victims at the hospital: “They refused with very few exceptions to be vaccinated nor was there vaccine within seven hundred miles to go around”.

As the visiting mostly un-vaccinated northern peoples were dying, the Songhees remained free of the disease. Thousands of the descendants of those vaccinated are here today.

The Opposition to Government

In 1859, a small group of colonial landowners were elected to the House of Assembly in Victoria. They became the vocal opposition to the Government of James Douglas. When opposition member James Yates put forth a motion to forcefully remove the Songhees from the Reserve in the Inner Harbour, John Helmken pronounced that it would be “a gross insult and if agreed to would be a lasting disgrace to the House”. Joseph McKay supported Douglas’s more human approach and declared that he did not think “committing robbery upon Indians the most praiseworthy method of making improvements” (Keddie 2003:59-63).

The opposition was strongly supported by Amor de Cosmos (William Smith), the editor of the British Colonist, who showed a general distain for Indigenous people and a hatred for the Government. He made this clear when he states in the Colonist on February 5, 1862: “God help us, if this semi-Indian regime exists much longer”.

This statement clearly makes reference to the fact that Douglas, Helmcken and his other main supporters in the House of Assembly were married to Indigenous women and Douglas himself was part Indigenous.

Figure 3. The original home of the Helmckens’ on the left and Douglas’s on the right in 1859. Cecelia and John’s daughter “Dolly” self identified as an Indigenous person and lived in the family home in later life until her death in 1939. The house was then acquired by the B.C. government and designated as a Heritage House. American National Library of Congress 08500-08559u

It should be pointed out, that even members of the “semi-Indian regime” held the paternalistic and now antiquated discriminatory ideas about the biology of Indigenous people common in this time period. But the important consideration is that the “semi-Indian regime” strongly believed that Indigenous peoples had rights that needed to be protected and the opposition did not.

Much of the information about the smallpox of 1862 was in the British Colonist newspaper. When reading it, one needs to be aware of the bias of its editor as a serious political opponent of the government. The Press newspaper tended to produce more in-depth stories of the smallpox situation than The British Colonist but also demonstrates negative views of Indigenous peoples.

James Douglas. Out of Town

Governor Douglas has been blamed for some actions taken by police during the smallpox epidemic in Victoria when he was not even there at the time. Douglas was compelled to leave town and deal with another crisis, the thousands of gold seeking miners rushing into the Interior from the United States and trespassing on the territory of Indigenous peoples. When the word got out that Douglas wanted to implement laws to control the miners, a committee representing miners forced Douglas to deal directly with miners in the Interior.

On February 14, 1862 the British Colonist prints the report of a committee representing miners:

“We, the miners of Cariboo residing in Victoria, do in the most emphatic manner denounce any or every attempt that may be made to legislate in relation to mining claims, and our objections may be summed up as follows: It can be supposed that mining interests will receive such considerations as they are entitled to anywhere so fully as in the mining regions where it is the duty and interest of all persons to give it the greatest protection. It is well know that a great many persons, in fact, nearly two-thirds of the Cariboo miners that are proprietors of mining claims by location, are now residing in different parts of the Colonies and other locations entirely remote form Victoria, consequently, great injustice would be done to such absentees if any action was had having a tendency to make laws where their interests are at stake. It is also well known that many persons not miners but residents of Victoria and other places have already invested capital in the mining claims of Cariboo, believing that no attempt would be made to make laws on the subject unless such action would emanate from the miners themselves when assembled at the mining locations. Your committee therefore consider that Cariboo, and not Victoria, is the proper place for action on this subject; and we believe that it is highly necessary for the welfare of the Colony of British Columbia that His Excellency the Governor refuse to listen to the appeals of individuals who are more anxious to acquire a transient notoriety than to advance the real interest of the Colony.”

Douglas was compelled to leave Victoria. The actions taken by the police forces in Victoria during the epidemic may have been quite different if Douglas had been around, as he believed more strongly in communicating directly with Indigenous people.

The Disease of Smallpox

At the time of the epidemic peoples ignorance of disease and even basic biology was sadly lacking. This continues to be the case in many parts of the world today. It was commonly believed in the mid 19th century that diseases spread from vapours coming out of the ground, which is why well meaning religious leaders in one Victoria incident removed the temporary building structures and blankets after a person died, burnt the ground around the area to “purify” it, and then returned the structure and blankets for the next person who had smallpox.

Even doctors that provided inoculation for smallpox in the early 1860s did not necessarily know the characteristic phases of the Variola caused disease. Smallpox was caused by two disease variants, Variola major and Variola minor. Variola major is a more serious disease and has an overall mortality rate of 30-35%. Variola minor causes a milder form of the disease which kills about 1% of those who get it. When the disease takes what are called the malignant and hemorrhagic forms, they are usually fatal.

Smallpox is highly contagious, but generally spreads more slowly and less widely than some other viral diseases, probably because transmission requires close contact and occurs after the onset of the rash phase. It’s transmission from one person to another is primarily through prolonged face to face contact with an infected person, within a short distant under two meters. It is also spread by people being in direct contact with infested bodily fluids or contaminating objects such as bedding or clothing.

Smallpox is not notably infectious in the period between the appearance of initial symptoms and the full development of a rash or fever. The incubation period between contraction and the first obvious symptoms of the disease is around 12 days.

The virus can be transmitted throughout the course of the illness, but is most frequent during the first week of the rash. Infection slows down over a period of one week to ten days when the scabs form over the lesions, but the infected person is contagious until the last smallpox scab falls off.

The overall rate of the infection is also affected by the short duration of the infection stage. In temperate areas, the highest number of smallpox infections are during the winter and spring. Age distribution of smallpox infections depends on acquired immunity. For those vaccinated, a high level of immunity remained for ten years but still persisted after that in lesser degrees. According to James Douglas smallpox vaccination was provided to indigenous people up to, at least 1853. This likely was responsible for providing immunity to some Indigenous people during the 1862- 1863 epidemic.

Virolation and Vaccination

Virolation

Virolation involves the use of a live smallpox virus and vaccination the use of a cowpox virus. Variolation gets its name from Variola – the scientific name for the smallpox virus. Variolation was an earlier method of inoculation first used to immunize individuals against smallpox (Variola) with material taken from a patient or a recently variolated individual. This was done for the purpose of creating a mild infection that people could survive. Infection with variola minor essentially induces immunity against the more deadly variola major form.

The procedure was most commonly carried out by rubbing powdered smallpox scabs or fluid from pustules into superficial scratches made in the skin. The patient would develop pustules identical to those caused by naturally occurring smallpox and after about two to four weeks, these symptoms would subside, indicating a successful recovery.

For thousands of years in the Old World this method was successful in most cases if done properly by knowledgeable people. Trained people who did this were, in various cultures, referred to by names that were the English equivalent of “inoculators”. However, because the person was infected with a variola virus, a severe infection could result, and the person could transmit the smallpox to others who had not been variolated (Edsell 196; McNeill 1976).

Vaccinations

The first vaccination against smallpox was performed by Edward Jenner in 1796. Jenner’s vaccination, used inoculation matter from the milder cowpox virus rather than matter from the live smallpox virus. As a milder disease carrying the same immunities, cowpox matter was much safer than the older variolation method. By the mid 18th century the old method of variolation, using a live smallpox virus, was still widely used in Europe and Asia. It was used in North America until the 1850s until supplanted by immunization through vaccination with cowpox liquid. But a major problem was having a sufficient fresh vaccine supply. This was especially a problem in remote places such as Victoria. Where vaccine was not available in large amounts arm to arm vaccination was widely adopted – as soon as a cowpox pustule appeared on a vaccinated persons arm, material from the lesion was extracted and used on another person’s arm.

It was the vaccination process that was used on many of the non-indigenous citizens of Victoria as well as Indigenous people that worked in the city and an unknown number of Songhees and other northern visitors. As stated in the Colonist for April 1, 1862: “one-half of the resident Victorians have had the cuticle of their left arm slightly abraded and vaccine mater insinuated”. Given the survival rate of the Songhees, we might assume that the early 500 inoculations undertaken by Dr. Helmcken also involved the use of the cowpox vaccination but the details of this are unknown.

Even the newer method of vaccination in recent history was only effective in preventing smallpox in 95% of those vaccinated. In Europe smallpox was the leading cause of death in the 18th century, killing 40,000 Europeans each year. There was often resistance to getting vaccinated on religious grounds. Refusal to vaccinate was also the case among some Indigenous peoples.

How Did Smallpox Come to Victoria?

The usual explanation for who brought the first smallpox to Victoria was a man on board the steamship Brother Jonathon that arrived March 12, 1862 from San Francisco with 350 passengers, about 125 of whom stayed in Victoria.

This person, however, had the more virulent form of smallpox, from the Variola major virus, and he was isolated in town. The disease events in show a slow speed and low death rate at first. This suggests that it was the milder form of smallpox, Variola minor, that was gradually spreading in town and then to the crowded camps of Indigenous peoples visiting from the north. We cannot rule out that the virus among the crowded Tsimshian camp did not spread from their camp in Puget Sound as they moved back and forth. The death rate for the Variola major virus at the time was around 30-35%, while the death rate for Variola minor was only around 1%. It is the latter pattern that fit the early outbreak of smallpox in Victoria.

I would suggest that the source of this less virulent form of smallpox remains speculative. There are other possible sources for the introduction of smallpox to southern Vancouver Island. Smallpox was already know in several American cities to the south and appears to have been brought by one of the American gold rush participants flocking through our Interior borders.

The Colonist newspaper reported smallpox a month earlier in the Boston Bar area of the Fraser River canyon than the first cases in Victoria. On February 14, 1862: “At Hope it was reported that the smallpox had broken out among the Indians at Boston Bar and that many had died”.

Around this time large numbers of people had been moving back and forth between the Interior of British Columbia and Victoria. The Colonist reported on March 18 that the smallpox was prevalent in San Francisco but had not been made public knowledge. It may be that other people on board the Brother Jonathon could have had the less virulent form and initially showed no symptoms?

A Chronological Summary of the Events of 1862 in Victoria

The sources of information of this epidemic reveal that there were different levels of understanding regarding the smallpox viruses and the safety measures that needed to be taken to deal with the crisis. It is important to note what activities and pronouncements were those of the government, the local police or the editors of the newspapers. I present a chronological summary of the events here as seen from Victoria to show how the disease changed and the reaction to it changed over time.

March 10, 1862. The British Colonist reported a influenza “Epidemic” of sore throats had hit Victoria having been prevalent in San Francisco over the winter where its effects killed many children.

On March 12th the steamship Brother Jonathon arrived from San Francisco with 350 passengers, about 125 of whom stayed in Victoria. It was later learned that a man on board this vessel had the viriola major virus but that he was isolated in town.

March 13: Colonist: “about twenty canoes, filled with northern Indians, arrived here yesterday”.

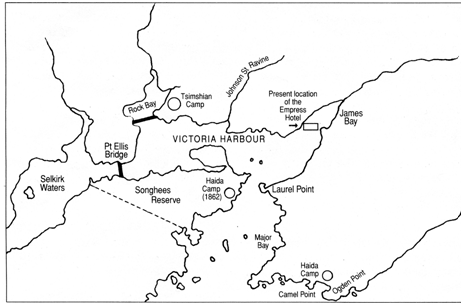

Figure 4. Victoria Harbour showing some of the Northern encampments in 1862.

March 18 – The British Colonist reports that: “For three or four days past rumors have prevailed in town… that the smallpox had broken out, and that several of the worst types were already under treatment. …one case of varioloid really exists here. The patient came from San Francisco on the last steamer.” The paper recommends that people going to the mines “proceed at once to a physician and undergo vaccination”. They reported that the smallpox was prevalent in San Francisco but had not been made public knowledge.

March 22 – As a few cases of smallpox developed in Victoria, a precautionary measure was undertaken to move some of the temporary camps of the northerners on the Songhees reserve to “camps up the Gorge & in the Esquimalt area”. The remains of the camps were burned. These camps were originally on vacant parts of the Reserve away from the Songhees houses.

March 26. Dr. Helmcken vaccinated about thirty Indigenous people, which included the Songhees chief and his family. The Colonist urged that stringent regulations be enforced to prevent the spread of the disease:

“Quarantine – We call the attention of the authorities to the fact that small pox has been introduced into this country from San Francisco. The cases may be few. But few as they are, they are dangerous; and as the harboring of such a disease is to injure this place, stop people from coming here, and endanger the lives of our citizens, we hope prompt measures will be taken to prevent it from spreading. The most stringent regulations ought to be enforced, and enforced without a moment’s delay. If a case occurs the parties ought to be placed beyond the reach of communicating the infection to others. Imagine for a moment what a fearful calamity it would be, were the horde of Indians on the outskirts of the town to take the disease. Their filthy habits would only perpetuate the evil; keep it alive in the community, sacrificing the lives of all classes. We have no wish to be an alarmist; but we believe there is danger, and great danger if the small-pox be allowed to spread through the neglect of the authorities. So much for the few cases noted already. But in reference to preventing its introduction from abroad, all vessels–steamers included–from San Francisco ought to be forced to render a clean bill of health before landing their passengers. If such be neglected, we fear that a serious evil will be entailed on the country”.

Figure 5. The Songhees chief Chee-al-thuc (King Freezy) and his unnamed wife were among the first Indigenous people to be vaccinated. RBCM PN06198.

March 27. Before he was to leave town, James Douglas took action to see Indigenous peoples inoculated. The Press: “Yesterday afternoon, all the principal Indians of the tribes now living here, were summoned to the Police office to have a “wawa” with his Excellency [Douglas] with regard to the small-pox. The result of the talk was that the Indians agreed to be vaccinated, thinking it was better to suffer a little pain rather than a great deal of agony. This morning, accordingly, about 30 Indians, amongst whom were King Freezy [Songhees chief], his queen and the young princess, and all the Indian doctors, were brought to Dr Helmken’s office and there underwent the ceremony of being vaccinated for the small-pox. It was pretty hard at first to convince them of the benefits arising from this very simple, operation, but after a while they were made to believe that the threatened sickness, the small-pox was far worse than their enemy, the measles”.

The same day the Colonist expressed: “The disease, we fear, will make sad havoc among the Indians unless stringent sanitary measures are adopted”. Many citizens of Victoria had been vaccinated.

March 28. There were only three cases in the non-indigenous community at this time. As isolated cases had appeared in previous years in Victoria there was no general state of panic. Colonist: Governor Douglas stated at the House of Assembly: “It is desirable that instant measures should be adopted to prevent the spread of the infection, and I would therefore strongly recommend to the House the immediate appropriation of a sum of four hundred pounds to enable me to prosecute such measures by causing a separate building, in an isolated position, to be devoted to the reception of the present cases, and of others that may occur; and making arrangements for their proper care and treatment”.

The Colonist reported that: “The physicians are daily besieged by applicants for vaccination” and that it was: “By order of the government, some thirty Indians were vaccinated on Wednesday by Dr. Helmcken”.

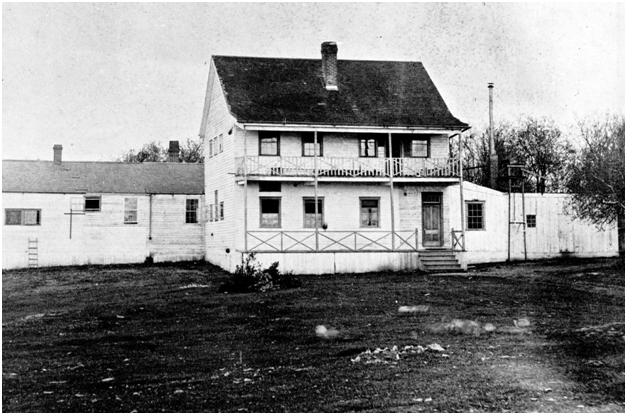

March 29. The Colonist reports that an order was given by the Police Superintendent for all First Nations to leave the downtown area and vicinity. They were not forced out of town, but asked to remove further up the Gorge Waterway. The paper indicated how this would create massive problems due to the many Indigenous people living with or working for Europeans. That day Dr. Trimble took action and proposed a bill to make the Royal Hospital on the Songhees Reserve a Government Institution rather than continually relying on charity. James Douglas, with the approval of the Songhees, had this hospital built on the reserve in 1859 for the use of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. John Helmcken was the doctor there for a number of years working with Indigenous peoples.

Figure 6. The Royal Hospital built on the Songhees Reserve in 1859 with later smallpox hospitals behind it. RBCM c_08843.

April 1. Colonist: “Vaccination – Nearly everyone goes in for vaccination now-a-days, and it is safe to say that at least one-half of the resident Victorians have had the cuticle of their left arm slightly abraded and vaccine mater insinuated. …To prevent the spread of the loathsome disease which so far has singled out three Victorians of this town, each good citizen ought to use every precaution, and his first duty to himself and the public, is to visit with his wife and little ones (if he has any) the nearest physician and undergo inoculation for the kin-pox [earlier name for smallpox vaccine]- no matter if he or they have been vaccinated before or not. An ounce of prevention, in the small pox time, is worth a great many pounds of cure, any day; and by timely attention to this no one can calculate the amount that may be saved in money and good looks – especially in the latter quality.”

Movement from the Interior to the Coast at this time involved both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people: “Cariboo Indians – Two Indians from Beaver Lake, 58 miles from the forks of the Quesnelle, are in town. They came as guides over the coast route with Mr. George Weaver, the well known prospector, who lately arrived overland from the Cariboo”.

The First Smallpox case among the Tsimshian Camp

April 3. Colonist: A person died in the Tsimshian camp. It was reported that the Tsimshian and Songhees will leave this day to isolate themselves on one of the Islands in the Straits. Two Chinese have the disease. Reverend Garrett built a smallpox hospital on the Reserve in which patients were placed immediately. The Colonist reports that all Indigenous peoples within the limits of the town, who do not live with non-Indigenous people, have been ordered to leave for the Reserve. In case there was any resistance, the gunboat Grappler arrived in the Harbour to enforce the Police orders.

April 5. The British Colonist: “Timely Warning – We learn from a perfectly reliable source that there are several children sick with the smallpox or varioid at the French Laundry on Government Street beyond Johnson. We give the public timely notice of these cases simply because there is unusual danger attending them. Very many of our citizens get their clothes washed there, which gives an unusual opportunity to communicate the disease throughout the town. We regret we have to be particular; but our only excuse is our regard for the public health”.

The Colonist goes on to associate smallpox with unclean conditions. In commenting on a manure pile dumped on a lot off Fort Street for growing onions, they suggest that: “From the smell in the neighbourhood, we should judge that he will raise a heavier crop of small-pox or cholera than esculents”.

Over 500 Now Vaccinated

April 26. Colonist: “Dr. Helmcken has vaccinated over 500 natives since the disease first made its appearance here”. “On Thursday several Nettinett Indians (who live near Cape Flattery) called on the Governor and said that they had been deputized by their tribe to ascertain whether there was any truth in a story told them by some white scamps that Gov. Douglas was about to send the smallpox among them for the purpose of killing off the tribe and getting their land. They were assured that they had been hoaxed, and left the next day for home”. The home of the “Nettinett” is incorrect here. They are the Ditidaht who live on the S.E. coast of Vancouver Island. At this time, it is most likely the Dididaht were on a trade mission to acquire whale oil across the Strait at Webster Point in Neah Bay, Washington State, as was reported in the Colonist two years earlier on August 2, 1860 where they are referred to as the “Nittenats”.

There is “a report going the rounds, to the effect that vaccine ‘scabs’ have become merchantable articles with the natives. They preserve them carefully and sell them for two ‘bits’ apiece” for the benefit of their brethren who remained above last winter, and are now looked for down. One of the old chiefs has gone into the vaccination business at the Indian village and expects to make a good thing by practicing as soon as the northerners get down”.

Smallpox Spreading Inside and Outside Victoria

April 26. Colonist: “The smallpox is reported to have reached Fort Rupert, but from which direction is not stated”. Rev. A.C. Garrett indicated that twenty people had died at the Tsimshian camp near Rock Bay.

April 27. The Press newspaper reported: “The Small-Pox Among the Indians – has broken out in the Simpsean Lodges, in the neighbourhood of Victoria, and that several deaths have already resulted. …Mr. Garrett intends to commence building a Hospital, on Monday, [28th] …A large number of Indians, probably over 500, have been vaccinated during the past six weeks. No danger need be apprehended to the inhabitants of the town – isolated cases of the disease having appeared among us for some time back, and no symptoms of its spreading become apparent. …it was thought to have entirely died away until the present sudden outbreak among the Indians took place.”

In a separate article they report: “Departure of the Songhish Indians – these old inhabitants of Victoria have determined to break up their camps during the prevalence of the small pox, and leave for other parts of the Island.”

April 28. The British Colonist, possibly because Governor Douglas is away on the mainland, calls for citizens to take more drastic action. After a long and very negative editorial criticising the presence of northern indigenous peoples in Victoria and fearing that the smallpox will spread among Indigenous people and then into the non-indigenous community, the editor spreads fear: “The Indians have free access to the town day and night. They line our street, fill the pit of our theatre, are found at nearly every open door during the day and evening in the town; and are even employed as servants in our dwellings, and in the culinary departments of our restraints and hotels. Even such as are employed as servants are in frequent communication with their friends, visiting or living on the Reserve. …It requires no further comment to show what a terrible scourge we are nursing at our doors – tolerating in our very midst – a scourge that may strike down our best citizens at any moment as a sacrifice. …No halfway measures can be tolerated with safety; nor no winning about the Indian trade can be allowed to interfere with the purification of the Reserve. We are assured that the Indians cannot be removed because the Governor is absent in British Columbia. The Police Commissioner can do nothing in his absence, nor no one else in authority!”

The editor suggests taking other citizen action to fill his suggestion that:

“The entire Indian population should be removed from the reservation to a place remote from communication with the whites; whilst the infected houses with all their trumpery should be burned to ashes”.

April 28. Colonist: The sick in the Tsimshian camp “are confined singly in small tents near the collection of Chimsean huts, and are cared for by their relatives and friends and supplied with medicines and necessaries from the Church Mission fund, by Rev. A.C. Garrett. …As soon as death occurs in a hut and the body has been removed, the house is torn down by its owner and the lumber removed to a new site, a few yards distant, and re-erected. The blankets and clothing used by the deceased are not destroyed. A few Chimseans have fled from the encampments and removed their families and household goods to small houses within the limits of the town. …The Chimsean at their village number, men women and children, some 300 souls – about ten per cent of which number have died or are hopelessly ill with the disease”.

The same day, The Press newspaper reports: “Removal of the Indians – Commissioner of Police, Mr. Pemberton, has taken immediate steps for the removal of all the Indians at present in town, with the exception of those who are in the employment of the whites. The Tsimpsean tribe have one day given them to leave this portion of the Island, and one of the gun-boats will take up a position opposite the camp to expedite their departure. … Songhish Indians express their intention of leaving for San Juan in a day or two.”

The Songhees Leave for Discovery Island

April 29. Colonist: Twenty three days after the disease appeared among the Tsimshian: “The Songhees Indians, greatly alarmed at the near approach of the disease, have loaded their canoes with iktas, and will leave for their Fishing grounds on San Juan Island early this morning. The Songhees chief “King Freezy says his tribe is ‘hiyou quash’, because of the infliction, which has fallen upon the Chimseans, but he firmly believes that they are visited by the smallpox as a punishment for their sins. Two or three loaded canoes from the northern encampment crossed the harbour yesterday, and from the appearance of things we judge that the occupants were bound for the [Johnson Street] ravine to take up their summer residence. Their presents in that quarter may prove highly detrimental to the health of the town. Three white people in the town are afflicted with the disease. Late evening orders were issued by the commissioner of Police to his officers to prevent the entrance of Indians into the town, and the Chimseans were given one day in which to leave the limits of the town, with their sick. One of the gun boats will assist in the enforcement of these orders.”

In another article The Colonist warns: “Get Vaccinated – We repeat our often expressed warning, to our town’s people to get vaccinated. The smallpox, in its most virulent form is creating fearful ravages, among the Indians, and it is the duty which every good citizen owes to society as well as to himself to get vaccinated. No person is secure without undergoing the operation at least one in seven years”.

The Victoria Press newspaper indicates: “Small-pox Vaccination and re-Vaccination – While small-pox in the unprotected is fatal in at least one forth the cases, it is so modified after vaccination as to cause death in only one case out of 50, or perhaps a hundred.” – “The Tsimpseans are still in camp, and the disease does not appear to be increasing”.

April 30. The Colonist: The Songhees left for their fishing camps on the Discovery and San Juan Islands to avoid the disease. Several patients are now in the small pox hospital and “All Indians within the limits of the town, who do not live with whites, have been notified to leave for the Reserve or their huts will be pulled down about their ears”. This refers to a move across the harbour to the vacated parts of the Songhees Reserve. More of the remains of the Tsimshian encampment are set on fire.

April 30. The Press: “The Tsimpsean tribe of Indians are to leave here this afternoon, and will probably locate on San Juan Island”. Six patients moved to the hospital.

May 1. The Press: “The Hospital erected by Mr. Garrett on the reserve, is at present occupied by 6 patients. They are attended to by a few of the Tsimshian tribe who have remained, and are in a fair recovered. The Tsimpsean burnt their houses and blankets and other ‘iktas’, without any compulsion from the police, and left this morning in their canoes. Only 3 huts remain standing, which are occupied by those of the tribe who have remained as nurses. Numbers of the Stickeen and Hydah Inds. have also left in canoes, and those that remain have moved their huts to a greater distance from the camp of the Tsimpsean. No case of small-pox has hitherto broken out among the other tribes, the disease having confined itself to the Tsimpseans”.

May 4. The Press indicates that one person died at the hospital and there were two new cases.

Smallpox Spreads Beyond the Tsimshian Camp

May 5. A full month after the appearance of the smallpox among the Tsimshian we see its spread to a Fort Rupert camp. But what is significant is that it was brought to Victoria rather that occurring in existing camps. The Colonist reported: “Two cases of the violent type have made their appearance among the Fort Rupert Indians who arrived here the other day.” This may be a significant event if in fact the “violent type” refers to the more deadly form of the virus. Because the Fort Rupert visitors only arrived the day before, the disease was acquired somewhere else. It may have been brought to Victoria to add to the less virulent form? In Nanaimo the smallpox had not broken out but “the Indians are being removed from their old camps to a point near the mouth of the Nanaimo River”. One Tsimshian died and a non-Indigenous person was admitted to the hospital.

May 7. There were ten cases in the hospital and 14 outside the hospital.

May 8 – Thirty five days have now passed since the smallpox first appeared in the Tsimshian camp in Victoria Harbour. The editor of the Colonist makes a major statement on his position on the smallpox and the removal of all indigenous people from the area. He shows his discrimination against both Indigenous people and the government very clear:

“Smallpox Among the Indians. We call the particular attention of the authorities, and all parties interested, to the spread of the smallpox of the most virulent type amongst the Indians. We would impress upon them the necessity of the prompt removal of every Indian, whether male or female, from the town and vicinity. They should be sent to some place remote from the whites, and that without a moments delay. Else we shall in all probability have to record among our white population many serious losses from the infection. Among the Indians the disease is making frightful inroads. The Chimseans were the first afflicted. There are now ten cases among them at the smallpox hospital erected by Rev. Mr. Garrett. Two Chismeans died yesterday morning. Three Fort Ruperts also died yesterday. The Rev. Mr. Garrett, after much difficulty, found seven cases among the Hydahs. They did their best to hide it from his knowledge. That shows what danger the community is in from the Indians. They prefer hiding the disease to making it known. One squaw has arrived each morning for the last three mornings at the Indian smallpox hospital, from the town where they had been living with white men. Thus we are nursing death in our very midst. At Ross’s farm there are twelve cases among the Stickeens. We ask, in the name of all that is hallowed how long this state of things shall last! It has passed into the proverb in this country, that “It is better to have the smallpox than have anything to do with the government ”, but are we apparently to be cursed with both? Gov. Douglas donated $100 dollars yesterday to relieve of the Indians. But what trifling it is with the lives of our own citizens to think private benevolence can afford the security for the public health that is demanded! Or that it can prevent the Indians from rolling with disease at our very doors. We hope that before this paper is dry in the hands of our readers this morning, steps will be taken by the clergy and fathers of families to protect the town by banishing Indians, and provide something like Christian assistance to the poor wretches who may be removed. There is no time to be lost”.

May 9. The Colonist: “The Chimseans passed Cadboro Bay over a week since on their way North. The Island on which they have settled is not known. The Indians encamped beyond Laurel Point were Stickeens”.

May 11. The Press: “Migrations of the Indians – The Tchimpseans, and remaining Stickeen Indians, were on the move yesterday, some of them destroying their homes by fire. The Queen Charolette’s [Haida] have been slightly visited by the prevailing epidemic, and were burning their lodges in the afternoon. The Hydahs intend to depart on Monday, [12th] en masse, after committing their dwellings to the flames. This is owing to the directions of the Police Commission. ..They will take up their temporary abode upon some of the many beautiful Islands that lie between this and the Plumper Pass.”

May 12. The Songhees on Discovery Island have not encountered the sickness. The Police are attempting to remove the Haida and Fort Rupert from the places allocated to them on the Songhees Reserve. The Tsimshian and Stickeen, with their sick, are encamped “on small islands in the Canal de Haro”.

May 13. The Press: “Conflagration on the Indian Reserve” – The Police proceeded to the Reserve this morning and destroyed all the lodges not comprised in the Songish village, by fire. “About 200 Hydahs were this afternoon sitting upon their ‘iktas’, having no canoes where with to transport them from Victoria.” The Colonist reports that “the northern Indians will be sent from the reserve today for one of the Islands in the straits – there to rot and die with the loathsome disease which is now destroying the poor wretches at the rate of six a day”.

Figure 7. The Haida encampment on the Old Songhees Reserve. The camp was cleared away during the epidemic but re-establishment as shown here in 1864 just before it accidently burnt down.

May 14. The Colonist reports on the movements of some Haida: “Dangerous – About 100 Indians are encamped on the pic-nic grounds at Cadboro Bay, and the settlers in that neighbourhood are alarmed lest the small pox should spread among them”. “The Small Pox. Yesterday the northern Indian huts on the reserve were fired by order of the police commissioner and burnt to the ground. Probably 100 huts were thus destroyed. The Indians were notified to leave Saturday last, and three days having lapsed and no notice being taken of the warning, fire was resorted to for the purpose of compelling them to evacuate, which they prepared to do yesterday afternoon after their houses had been levelled to the ground. About 22 cases were reported yesterday by Rev. A.C.Garrett , … the deaths average five per diem. In the Indian smallpox hospital ten patients were to be seen yesterday. …The numbers of deaths among all the tribes at present on the reserve will research, if not exceed 100, the deaths among the tribes encamped on the Islands in the Canal de Haro will probably reach a like figure – the work of death seems only to have commenced. We should not be in the least surprised if the disease were to visit and nearly destroy every tribe of Indians between here and Sitka. … the new building at the rear of the Royal Hospital, for the reception of patients of this kind, is approaching completion, and will be ready in a day or two.”

May 15. The Press: “The Indians – As many of the Indians ejected from the encampment, went no further than Cadborough Bay, a detachment of police visited the spot yesterday afternoon and compelled them to continue their journey. A large number who had squatted just beyond Mr. Laing’s ship yard, were this morning dislodged, and directed to leave the neighborhood.” The latter were Tlingit “Stickeens” camped at Fishermans wharf, then called Major bay.

The British Colonist reports that: “The Indian huts at Esquimalt have been destroyed with fire by the police, and the occupants directed to Clattawa”. These were the people mentioned earlier in Esquimalt Harbour.

May 18. The Press: “Tis an Ill Wind Etc. – We have to record a new demand in the labor market. Owing to the visiting of small-pox, and consequent departure of the Indians the lumber yards are obliged to substitute white men for native employees. Some newly arrived immigrants were on Friday discharging a cargo of lumber at $2.50 per day”.

New Smallpox Hospitals

May 19. The government has now built two smallpox hospitals on the Reserve. One is for the seven sick Indigenous patients and the other for the four convalescents. The small pox is spreading among the encampment of Tsimshian visitors at Port Ludlow in Puget Sound, Washington – “many of whom have died and nearly all down with the disease”.

May 22. Not all of the Haida have left the inner harbour as one was arrested on suspicion of stealing from the miner’s encampment on Rock Bay and another was murdered nearby.

May 24. Colonist: “Dr. Helmken on Thursday sent a half breed child, afflicted with the smallpox, to the hospital. The bodies of three Indians, who died from the same disease, were yesterday reported festering in the sun on the beach at the rear of the government buildings”. At this time the Haida were still “encamped in great force beyond Hope Point; above the site of the old Bridge”. This refers to the Johnson Street Bridge that was torn down earlier that year.

May 26. Colonist: “Encampment of Hydahs at Ogden Point” – 20 of 70 dead. Next day the Haida left. “Cadboro Bay Indians” [Haida camp] threw their dead into sea.

The editor quotes from the British Register Generals Report for 1859 making the point about how many children died in Britain because of not getting the smallpox vaccine: “3848 persons, chiefly children, who had not been vaccinated, an instance, as Dr. Farr remarks, of the rigor with which the infringement of sanitary laws is visited, for the children perish and the people lose their offspring by the neglect of a precaution of the simplest kind”.

May 27. Colonist: “The Small-pox” – Rev. Garret & Police went to “Ogden point” near the “mouth of the harbour”. [This is likely the unnamed bay to the south of Camel Point]. Thirty out of seventy of the Haida had the disease. The number of dead is not definitely known but if numbers could be obtained “it would be ascertained that at least one third of all the northern Indians who were until lately encamped on the reserve or resided with townspeople as servants have already died. Hydah Indians found dead at the brick kiln murdered by other Indians”.

The Press: “Indians at Cadboro Bay – We learn from a farmer …that a number of Hydah Indians are still encamped on this spot. The smallpox is raging amongst them, and several deaths occur daily …They have a tent erected apart from the rest of their dwellings, which they use for the purpose of a hospital. …Two of the Edensah’s brothers, and another Indian, called at the house of our informant on Sunday, and were very disorderly. They told him ‘that the police paid no attention to them, and they could get as much drink as they pleased.’ …half of the number come into town daily”. It is this group of Haida who are referred to as the “Cadboro Bay Indians” who are “throwing their dead into the sea”.

Compulsory Move for all Indigenous People not employed in Town

May 28. The Press: “Compulsory Departure of the Indians – …those persons in whose employ are Indian servants, can obtain a certificate granting them permission to stay, by applying at Mr. Pemberton’s office. All vagrant members of the tribes will however be required to leave forthwith”. Several cases of smallpox occur among a family of Kanakas on Humbolt Street.

The Colonist reported: “Turning them Out – The Police seem determined to rid the town of every Indian man and woman adjoining within its limits, and to accomplish that end have warned them that they must leave with bag and baggage within the next twenty-four hours. Three small-pox patients, among the natives resident in the town, were discovered on Monday, and sent outside of harbour”.

May 31. Colonist: Eighteen cases occur at the small pox hospital and seventeen at Ogden point where three bodies lie unburied.

June 2. Colonist: Seven deaths occurred at the northern encampment. The Colonist notes: “not a single Flathead [Songhees] has, as yet, fallen a victim – a fact which seems all the more strange when it is borne in mind that many of them have not been inoculated with the kin pox”. The editor seems to be unaware of vaccinations that had occurred earlier in the 1850s as mentioned by Douglas. The editor complains that Indigenous women living with white men can get a permit to stay in town, while: “Honest and well-disposed Indians, who had been vaccinated and were employed in town as servants, have been driven north by the Police for no other reason than that they are Indian”. “The little half-breed boy taken to the hospital last week, from Kanaka Road, afflicted with the smallpox, expired yesterday afternoon”.

June 4. The Press: “Police ejecting Indians from Ravine near Johnson Street”. People are now dying of small pox at Nanaimo.

Figure 8. Shanties in the Johnson Street ravine where some indigenous visitors lived during the summer. Looking west across to houses at Limit Point on the Songhees Reserve. Frederick Whymper 1864.

June 5. The Daily Evening Press: “Small-pox – The mortality among the Hydahs, lately encamped at Ogden Point, has been frightful, over 20 bodies being left dead upon spot, some unburied. The remnant stampeded a day or two ago, leaving houses standing, provisions, blankets, and every other description of property promiscuously in the camp. The Police were engaged to-day burning the huts and covering the bodies with lime.”

The same day the Colonist reports: “The Small Pox – Mr. Sopfall, in charge of the Indians smallpox patients at the Reserve, reported 27 cases yesterday and 3 deaths…Out of 100 Indians who encamped at Ogden’s Point four weeks since, about 15 remain alive, and but few of the Chimseans who were sent to the Island near Cadboros Bay are left.” The smallpox is “affecting Kanakas and Whiteman on Quadra Street”.

June 6. Colonist: “Yesterday it was found that Hydahs in the neighbourhood of Ogden Point had left taking their sick but leaving all possessions behind. Out of 100 Indians who were encamped there two weeks ago not one could be found”. Only 10 or 12 left from disease fled. Houses burned & quick lime “was thrown thickly over site of the encampment”.

Another article notes: “Smallpox in the Ravine – has broken out among the Indians living in the ravine, back of Johnson Street”. The article suggests they should be sent back to the Reserve. The Press reports six more people in the hospital and that Mr. Lopdell is “kept continually at work making coffins”.

June 7. The Colonist reports six new cases in the smallpox Hospital, four of which are “from the camp in the neighbourhood, one was employed by Mr. Cox, ..other employed by another resident”. Two died. “They were Stickeens. We are informed that no remedies of any description were given them”. The Press reported the next day that there were 29 patients in the smallpox hospital on this day.

June 9. The Press: “Removal of the Indians – Complaints of vagrant Indians not being removed …about 30 new dwellings have been erected on the reserve, whose inmates laugh with contempt at the continued asservations of the authorities that they will be compelled to leave”. “Small-pox – a young Indian child in house on Store Street died”. It is reported that there were six new patients every day in the smallpox hospital.

June 10. Only a few of the Tsimshian “sent to the Island near Cadboro Bay are left”. “Smallpox in the Ravine – Yesterday morning a half breed baby, said to be a child of Policeman Weihe, died in the ravine of smallpox”.

June 12. Colonist: “Good Bye to the Northerners – Yesterday morning Mr. Police magistrate Pemberton, with Superintendent Smith and an effective force of police, repaired to Cadboro Bay and supervised the embarkment for their homes of about three hundred northern Indians. Twenty six canoes in all, containing about three hundred native men, women and children, departed about 10 o’clock. One of the gun boats remained within hailing distance of the camp, in order to render assistance to the police, should any obstreperous conduct on the part of the Indians occur. The poor creatures protested feelingly against the injustice of the proceeding, but maintained no desire to resist the stern mandate of the law. Edensah, chief of the Hydahs, reported only one sick man in the tribe. Twenty of the canoes were neatly filled with Hydahs, five with Queen Charlotte Islanders, and one with Stickeens. The gunboat, at the urgent request of the chief, will accompany and protect the Indians until they are passed Nanaimo – the Indians of which place have many old score to wipe out in consequence of outrages received at the hands of the northern brave in years gone by, when the latter were the terror of the coast”.

Military Ships Assist in Inoculation

June 13. The Press: “Small-pox Among the Indians – The Sloop Hamley returned from the coast of B.C., reports that the Indians are everywhere dying, under the most malignant form of the fell disease.” – “Hundreds presented themselves aboard and eagerly demanded to be vaccinated. Our doctors did all who applied. Many had been only done a few days before by M. Moffat of the H.B.C. Co,” Richards reports at Fort Rupert. Beaver Harbour. Smallpox raging – 16 cases, 5 died.

The Colonist reports: “From the N.W. Coast and Stickeen” …The Indians at Fort Simpson and Rupert are dying from the smallpox like rotten sheep. Hundreds were swept away within a few days.”

June 14. The Press: One person was found dead at Cadboro Bay and only now are some of the decaying bodies being removed at Ogden Point. Hundreds of Indigenous people at Fort Simpson and Fort Rupert are dying from the smallpox. The Colonist: “Lo! The Poor Indian! Capt. Shaff , of the Schooner Nonparell, informs us the Indians recently sent north from here, are dying very fast. So soon as pustules appear upon one of the occupants of the canoes, he is put ashore; a small piece of muslin to serve as his tent, is raised over him, a small allowance of bread, fish and water doled out and he is left alone to die. Capt S. Reports seeing many such cases on his trip down, and is of opinion that all of the Indians not vaccinated will die this summer. What were are philanthropists about that they were not up the coast ahead of the disease two months ago, engaged in vaccinating the poor wretches who have since fallen victims. Who among our missionaries will volunteer to save our aborigines from utter extermination.”

The Songhees Enforce Isolated

June 15. Colonist: “Indian Murders – On Sunday last a number of northern Indians in a canoe attempted to land at Discovery Island, near the spot where the Songhees Indians are encamped, but were warned off by King Freezy, who alleged as a reason for his inhospitality that was afraid of the small-pox. The northerners persisted in attempting to land, when they were fired into by the Songhees, and one of their number killed. The canoe then put off, when several more shots were fired and another Indian and a squaw were killed and several wounded. The survivors, by dint of hard paddling, escaped to this Island, landed near Cadboro Bay and made their way back to the reserve”.

June 16. The Press: Fear and discrimination in attitudes are seen in the reporting of this day: “More Small-pox in Town – Indian found in shanty between junction of Johnson, Douglas and Bunster’s brewery. Immediately round the same dwelling are about a dozen small tenants, several occupied by white families, some by degraded whitemen co-habiting with squaws and the remainder dens of Indian prostitution”.

June 17. The Press shows further discrimination: “For four years Victoria has suffered to an extent unknown in any civilized town in the universe from the residence of an Indian population …’cheap’ labor at the expense of a white immigrant population”. The Colonist: “In the Heart of Town – An Indigenous occupant of one on the small shanties near the corner of Douglas & Johnson streets died yesterday morning of smallpox”.

The same day Captain Richards reports that in Nanaimo he: “Found all the Natives had been removed from the town for fear of small pox”. John Booth Good, Anglican missionary at Nanaimo: “[We] kept vaccinating young and old for days and with the aid of the new coal company we succeeded in removing the Nanaimo Indian proper to a new site within their own reserve, white washing their dwellings, and instructing them in sanitary precautions to prevent any further spread of the disease”.

June 18. The British Colonist: “Another body was found in the bush and a native on Meares Street and a white man on View Street are sick”.

June 19. The Press: “Nothing can really be more alarming that the present condition of Victoria. We are but little past the middle of June, and the disease which has been decimating, the Indian population has begun to take hold on the white”. “The Small-pox” – fresh cases “A Canadian who has been sick for some time, was today removed to the building rear of the Royal Hospital.”

June 19. Colonist: “Small Pox. “The ravages of this most frightful disease continue unabated. It is said that there are at least ten white patients undergoing medical treatment within the limits of the town at the present moment, and the number of Siwashes afflicted with the disease it is really impossible to estimate. Yesterday morning the body of an Indian, who had died of the small pox, was found in the bushes near the residence of Wm.Rhodes, Esq., by some coloured children who were gathering flowers. An American died of the same complaint at New Westminster on Saturday last. The disease seems to be on the increase, and we are daily in the receipt of suggestions from many citizens who favour the calling of a public meeting, and the formation of a Board of Health – a very necessary measure, and one which would no doubt receive the hearty co-operation of the authorities, who have thus far shown themselves nearly powerless to deal with the question. Fresh cases and deaths are occurring daily, and the woods contain the decaying bodies of many human beings. The streets are in a deplorable unhealthy state, and the town generally seems in a splendid condition for the further spread of the pestilence among the white population. Something should be done, and done quickly.”

June 22. The Press: “More Victims of Small-pox” – a family in Waddington Alley and an American.

June 23. The Press: “Death by Small-pox – a young Canadian named Hall”. “Vaccination at Fort Rupert – by surgeon of H. M. S. Hecate, …smallpox ravaging amongst them”. The Colonist reports that: “A Canadian and a half-breed child are now the only inmates of the Smallpox hospital.”

No Nanaimo Smallpox

June 24. Colonist: The HMS Hecate arrived in Victoria with news that “no Nanaimo Indians are suffering from the smallpox. …At Fort Rupert Drs Wood and Kendall, of the Hecate, humanly vaccinated a large number of natives”.

Governor Douglas to establish a Board of Health comprising the Directors of the Royal Hospital, and create a law giving them power to investigate unhealthy conditions on private property.

June 25. Colonist: “Small-pox at the Police Barracks – Yesterday it was ascertained that Policeman Weihe, who was ailing for several days, had been attacked by the smallpox in its most virulent form, and his removal to the small-pox hospital was at once made. This officer it will be remembered was detailed to attend the burial of Indian bodies at Ogden Point and Cadboro Bay, and the destruction of their clothing and tenements. Never, having been vaccinated, he has fallen a victim to the loathsome disease, the ravages of which he was using his utmost exertions to arrest. … several of the policemen have been freshly vaccinated, an considerable alarm is felt least the disease may attach other members of the force”.

June 28. Colonist: In the northerners’ camps at Cadboro Bay, bodies of smallpox victims were weighted down and thrown in the water by their relatives. “Latterly, the Songish Indians refuse to eat of fish caught in that vicinity, saying they are sick. The same course was pursued towards the bodies of the defunct smallpox patients at Ogden Point”.

June 30. Colonist: “Can’t Get Rid of Them – 30 Indians have encamped at Hospital Point, Esquimalt, & the naval officers accordingly scramble for the safety of their men”.

The Smallpox Among the Kwakwaka’wakw

July 1. Colonist: “The Euculets – This late powerful and warlike tribe, residing for centuries near Cape Mudge, on the west [east] coast of this Island are dying from smallpox in scores. The way the disease first spread among them is this: For many years they have been at war with the Hydaas, and espying one day recently a canoe containing four or five ancient enemies passing the encampment, they put out and murdered the occupants. And took possession of all their traps. The plunder thus obtained was divided among the thieves, and in a few days the dreadful disease broke out in the tribe”.

“Bishop Hills, now on his way to Cariboo, personally visited the Lillooet villages and vaccinated all the natives who came forward for that purpose. The Bishop, our informant says, is well provided with vaccine matter, and will similarly treat all Indians through whose country he may pass. Great pity a movement of the kind was not inaugurated by Bishop Hills on the Island and coast of British Columbia months ago”.

Rev. J. Sheepshanks, who was with Bishop Hills during the visit with the Fountain Band, indicates where the vaccine came from: “I took advantage of this time to vaccinate the tribe. Just then the small-pox, for the first time introduced, was making terrible ravages among the native tribes, and before starting on our mission I though it well to get some instructions in the art of vaccinating from Doctor Seddall, the good doctor of the Royal Engineers, who gave me a quantity of dry vaccine matter, and also a lancet” (Duthie 1909:67-71).

July 2. Colonist: “Arrived on the Gunboat Forward – Her Majesty’s gun boat Forward, Capt. Lascelles, arrived yesterday afternoon from Ft Rupert, via Nanaimo. While passing up the Ganges Harbour, Salt Spring Island, the Indians being towed by the gunboat were fired at by the Cowichan Indians. ,,,A few cases of small-pox occurred among the tribe that were conveyed North by the Forward”.

July 7. Colonist: Rev. Mr. Fouquet, a Catholic Missionary, returned to New Westminster on Wednesday last [July 2] from Lillooet Flat, wither he had gone to vaccinate the Indians”.

July 11. Colonist: A hundred bodies are reported along the coast north of Nanaimo.

Smallpox hits Duncan and Sooke

July 14. In reference to the Duncan area a letter to William A. G. Young: “The smallpox has made its appearance here …nearly all have now left for the different islands through fright.”

August 7. Colonist: The small pox is attacking the Sooke and has killed “Charlicum, the big chief”.

August 8. Colonist: “Small Pox Hospital – Two white men afflicted with the small pox, are at this institution”.

August 17. Colonist: “Captain Mountford of the schooner Northern Light “Bute Inlet Meeting” Left Bella Coola 18 days ago. Came overland from Alexandria. “The Indians in the Interior are healthy and friendly; At Bella Coola nearly the whole tribe has been swept away by the smallpox, and at Deane’s channel but one Indian was seen”. This would indicate the disease was in Bella Coola at the end of July.

August 18. Colonist: Smallpox broke out again “among the Indians in the ravine back of Johnson Street”.

August 26. Colonist: “Small Pox – Half-a-dozen cases of smallpox are still on the Indian Reserve [northerners camps]. It is reported that a young white man, living on Yates Street, is suffering from an attack.”

September 4. Colonist: “Great Mortality – The Stikeen Indians, a tribe that four years ago numbered, 1500 warriors is now is now able to muster only about 150”.

September 8. Colonist: “Two white men, afflicted with the small-pox” are at the Small-pox hospital. “Royal Hospital – At this institution there are at present writing 27 patients – 9 more than the capacity of the building will accommodate with any degree of comfort. “Epidemic – Sore throats, coughs and colds in the head are epidemic in Victoria this season. Nearly every person one meets has a cold in his upper story, and not a few are laid up with one or both complaints. To the cool nights, we are enjoying, the epidemic is attributable”.

The “young and the strong” affected in Fort Rupert.

September 11. Gowlland at Fort Rupert noted: “the smallpox which went through the Indian tribes about 3 months ago did not ease off these poor fellows”. He indicated that there were previously 400 men and now only 50. The disease appears to have “principally attached the young and strong” (Dorricot 2012:210).

Among the Haida off Anthony Island Gowlland notes: “the traces of the small pox visible amongst them yet; but the height of the Malady has passed, hundreds of them have died” (Dorricot 2012:212)

September 16. Colonist: “Death from Small Pox – Moses Fisher, age 33, ..at the small pox hospital .. Deceased was lately from Cariboo”. There is also a report of a smallpox victim found in the woods near Mr. Finlayson’s farm.

September 18. Captain Richards while off Fort Simpson noted that “the tribe originally number 2000 men, but the late smallpox and disease incidents in intercourse with white man have brought them down to Half that Number”. Gowlland notes that “600 of them out of 2000 have already died; even now it is raging in the camp; numbers of their houses we see shut up and Marked” (Doricott, 2012:217-218).

October 9. Colonist: “Seven Indians have died [in hospital] on the Reserve of small-pox within the past ten days. Two patients only are now there”.

Fear from the small pox in Victoria has now resided.

October 20 – Colonist: The fear from the small pox in Victoria has now resided. The Colonist reports that the Songhees have returned to their village on the Reserve to spend the winter. “The site of the encampment has for the last few days presented a most animated appearance; canoes coming and going continually, and the work of rebuilding the lodges destroyed by the late fire progressing rapidly. The proximity of this tribe is not necessarily the cause of so much demoralization to the white population, and injury to the labor market, as resulted from the presence of the large number of Northern Indians”.

Oct. 21. Colonist: “Addition from Stickeen”. “The small-pox was raging among the Indians at the mouth of the river – six or seven dying daily.”

Nov. 14. Colonist: “The Smallpox is still continuing its ravages among the Indians in the vicinity of Sooke, several deaths having occurred of late.”

Nov. 24. Colonist: “Smallpox again” – native convicted of Burglary in Alberni has small-pox – “He was transported to the Indian Hospital”. Another died “in a small shanty in the ravine”.

Nov. 29. Colonist: “Small-Pox” – Two cases of smallpox among a family of young children are reported to exist on Humbolt Street.”

Dec. 1. Colonist: “Police Court – Jim, a Hydah Indian, whose face exhibited sores that looked very much like smallpox, was charged …living with women of different tribe” – she died of smallpox and he threw her body in the harbour.

Dec. 3. Colonist: “Death from Smallpox” – non-indigenous women “near gov. farm”. “Small Pox at Cowichan – This disease is committing great ravages among the Indians at Cowichan”.

Vaccination Checks the Smallpox Among the Cowichan

Dec. 4. “The Cowichan Indians” – smallpox victims “vaccinated and the progress of this destructive epidemic effectually checked.”

December 8: Colonist: Death of Lopdall, “who was formerly in charge of the Indian small-pox hospitals”.

Dec. 9. Colonist. “From Cowichan – A few deaths from smallpox were still occurring among the Indians – the victims, rather singularly, being chiefly old women. The old people of the tribe relate that some thirty or forty years ago there was a similar state of affairs to the present – that the weather was very foggy – hiyou smoke – and that there was an unusually plentiful catch of salmon, but that the Indians did not live to benefit by the abundance, the small-pox having cut them off in great numbers; they are consequently in great fear that a like calamity may now befall them”. This smallpox outbreak occurred about 1832.

Dec. 18. Colonist: Smallpox – “a Coloured man died on Johnson St. near Broad”.

1863

January 3. Colonist: The report of an Indigenous woman with smallpox living with a white man on Humbolt Street was not reported by her partner and taken to the hospital. It is recommended that a city regulation provide for a city inspector rather than the police take on the job of removing infected people from the city.

January 5, 1863. A four year old child of a Haida woman died on Humbolt Street. In the Interior, at Beaver lake: “Small-pox has committed fearful ravages, sparing neither white man nor Indian; five of the former and above forty of the latter were cut off by this fearful epidemic.”

Amour de Cosmos Pushes to Remove the Songhees Reserve Again

January 9, 1863. Even though the smallpox is still occurring in the city, Amour de Cosmos, the editor of the Colonist, uses the experiences of the smallpox to yet again bring up the question of removing the Songhees Reserve: “A few years ago the sight of a Hudson Bay Company’s Fort, with a handful of whites, would be enough to account for the very prominent part filled by the Indians in its neighbourhood. The fort has disappeared; a city of the white race occupies its place. The refinements of civilization have been introduced, yet King Freezy [the Songhees chief] and his fishy, clam eating subjects are still located upon what ought to be part of the site of the city. In no other county would such a state of things be tolerated. It is neither just to the whites nor to the Indians. The latter would be much better off if removed to some distance from the city and its corrupt influence, while they would reap the benefit of the value of the land belonging to them on the reserve. This land is naturally a part of the city and ought to be surveyed into lots and streets”.

January 15, 1863. Colonist: In the Interior coming from Quesnel, Mr. Weaver travelling on a new trial on Black River came across the village of Klonsears where only one child of a population of about 80 survived the smallpox. At Lillooet there were four cases of smallpox among white men, one died. “Measles had broken out amongst the natives, but not to any serious extent”.

January 23, 1863. Colonist: Lillooet and Douglas Lake area – “There have been no deaths from small-pox at the former place since our last advices, but in Douglas two Indians died and many more were ill. Several cases had occurred among white people, and one was not expected to recover. The Indians were leaving for the mouth of Harrison River and the Sumass”. Many Indigenous people from the lower Fraser River worked in the Interior during the gold rush as packers and panning for gold themselves.

January 30: Colonist: At Lillooet – “At the rancheries near this place sixteen Indians are ill with the smallpox and several have died”. Three white men died of the smallpox, two at Beaver Lake and one at Canoe Creek. Regarding the $2500 allotted to the Royal Hospital “Dr. Helmcken said he hoped it was understood that the sum was to be applied only to the support of the main establishment, and not to that of the small-pox ward. He stated that the latter had been erected by the Government under an understanding with the hospital committee that all those admitted who had the means were to pay their own expenses, though the destitute were to be accommodated free. He objected to the way in which the city council were hunting up and sending over patients. If they turned people out of their dwellings who had the small-pox, the Corporation should provide a place to send them to.” The Royal hospital was overcrowded, as it was only built to accommodate 20 people.

January 31. Colonist: “We are surprised to find that Dr. Helmcken in his place in the house of assembly raised objections to the city council sending persons inflected with smallpox to the Hospital.” The editor promotes having the city inspector continuing his “zeal” for finding out and bringing people to the hospital.

February 10. 1863. Colonist: There are 10 patients in the smallpox hospital.

February 21, 1863.. Colonist: The editor responds to a story in the Oregonian newspaper of Oregon full of misinformation about the smallpox. It is seen as “a means to prevent immigrants from coming to this country. …We ask our Portland contemporaries to deny the statement that smallpox prevails with any such virulence in this country. Dr. Helmcken, a few days ago, stated in the assembly when an appropriation was voted for Hospital purposes, that no cases of small-pox were now reported among the whites. We consider him first class authority to refute any such false and injurious statements as that spread abroad by our cotemporary. There is no danger here from small-pox than in San Francisco or Portland.”

The Interior Scene

February 26, 1863. Colonist: Beaver Lake – Indigenous people with smallpox in area.

February 27, 1863. Colonist: “The Indians from the forks of Quesnel, down to and including Lillooet, have nearly all been carried off by the epidemic, which has been raging among them all the season. The survivors have sad tales to tell of the dreadful scourge which has wrought such fearful havoc among their friends. At Lillooet report sets down the number of natives who have succumbed to the violence of the disease at 170, and what was once a powerful tribe of warriors is now reduced to a few miserable beings”.

March 3, 1863. Colonist: “Royal Hospital – There are fifteen male and two female patients at present receiving treatment in the Hospital. In the Small-pox ward there are only four patients, all of whom are convalescent, and will be discharged in a few days. We are happy to state that smallpox is on the decline in the city, there having been no new cases reported for some time past”.

The Disease Nearly Gone

March 12, 1863, Colonist: Report from people returning from Haida Gwaii: “Smallpox we understand has disappeared from among the northern tribes of Indians, after having in some instances, swept off whole villages”.

March 21. 1863. Colonist: Report of February 24th from the Cariboo: “there had not been a case of smallpox in the upper country for some time”.

Discussion

In 1862 smallpox spread mostly among Indigenous peoples visiting from the northern coast. As the northerners returned home the disease spread along parts of the coast and through parts of the Interior causing major destruction. How far the smallpox spread from that early Interior report in Boston Bar and in what direction it spread from that location is unknown. It appeared in Boston Bar a month before it was observed in Victoria. Isolated cases had appeared in previous years in the non-indigenous community of Victoria without affecting Indigenous peoples. It also occurred sporadically in the town of Victoria in 1862 before it took hold on the visiting Indigenous communities.

In Victoria, the spread of the smallpox was influenced by northern Indigenous visitors living in crowded conditions at temporary camp sites, as well as a result of the northern unvaccinated visitors moving about and in some cases bringing the disease with them from other locations. Locally people moved between the crowded camps and small shacks in the city around the Johnson Street ravine. Many Indigenous people lived in the city while working for non-indigenous employers and Indigenous women lived in the city with non-indigenous men.

Before Douglas left town for the Interior and before there was evidence of an epidemic, precautionary measures were undertaken to move some of the temporary camps of the northerners and to build a smallpox hospital. Dr. John Sebastion Helmcken began providing vaccines to local Songhees and others when signs of the virus first appeared. He had vaccinated 500 people in the first six weeks. We do not know how many indigenous people were vaccinated by Helmcken after that but it was likely at least several hundred more.

Helmcken played an important role in saving the lives of Indigenous people, not just during the epidemic but during his caring for patients in the Royal Hospital on the Reserve before and after the epidemic (Keddie 1991). In 1862, Helmcken was the chairman of the Royal Hospital when an additional detached ward for smallpox patients was built by the government and maintained at their expense.

This concern for Indigenous people in the Helmcken family was continued into the next generation when his lawyer son Henry worked for the Songhees in getting an exceptional settlement in negotiations for the movement of the Old Songhees Reserve to its present location. At that time, his sister in law Martha Harris publically defended a woman who lived on the reserve but was initially prevented from getting the $10,000 compensation given to each family head because she was married to a Cowichan man (Keddie 2003).

Cecelia Helmcken was an indigenous woman who, with John raised seven children in what is now known as the Helmcken House. Their daughter Edith Louise, known as “Dolly” self identified as an Indigenous person. She took care of her father until he died and continued to live in her family home until she died on April 13, 1939. Their home was then purchased by the Provincial Government as a heritage building. The Douglas family home was taken down and the location now buried under the Royal B.C. Museum.

Factors in the Number of Deaths

There are a number of unknowns regarding this epidemic. The role of the flu in some of the deaths is unknown. The Colonists reports on Sept 8, 1862 that it was a particularly bad flu season.