By Grant Keddie

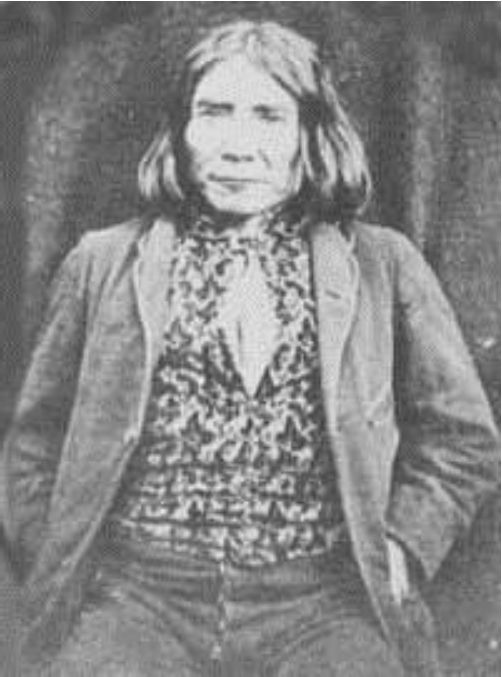

James Squameyuqs–Songhees Chief 1864-1892

James Squameyuqs (Grand fir tree), also spelt as Scomiak, Comey-uks, Kumayaks, Skomiax, Skomiak, Scomiax and Somiax, was born about 1797. On 12 November 1864 he became the second chief of the Songhees since the founding of Fort Victoria.

“Comey-uks” is the second person listed on one of the aboriginal treaties made by Governor James Douglas in 1852. This treaty was called the South Saanich Treaty, but included the area south of the territory of the Saanich people, from Cowichan head to Mount Douglas. Songhees band member James Fraser related how his grandfather, the first Songhees chief, named Freezy, or Chee-al-thluc, “invited James Kumeyaks of Sidney Island to move to Victoria”. In 1867 Squameyuqs’s home was “at the top of Johnson Street”, on the reserve on the west side of Victoria harbour. Others from Sydney Island moved to the East Saanich reserve on Saanichton Bay. After Scomiak became the chief of the Songhees, there was an attempt to move the band to Squameyuqs’s fomer home on Sidney Island.

Squameyuqs died on 12 September 1892 after a “prolonged battle with consumption”. The day after his death, the Victoria Colonist published:

“Scomiak Is No More – The Veteran Chief of the Songhees Tribe He Proved Himself a Capable Leader” “Over on the reserve flags are flying half-mast, the canoes are drawn up on the muddy beach, and the tribesmen . . ., with their sympathizing friends of the Cowichan, Saanichs and Beechy Bays, are telling the history of men, women and children remaining to claim the name of Songhees. The death of the Chief again directs attention to the little kingdom over which he reigned . . . and from which he declared, less than a year ago, he would never be carried alive. That was when the Council, taking up a subject that has long been . . . a source of continual annoyance to Victorians, declared that the reserve . . . could no longer remain as almost the centre of a busy city The legislature of the province did what it could toward facilitating the occupation of the reserve by the city, after making sure that a new and suitable home would be found for the Songhees . . . where the smell of the salmon and the camp fire would not offend sensitive city nostrils, and the clang of the railway train and electric car would not disturb the Indians But the old chief refused to see the question in the light the city people wanted him to, and the tribesmen stood by their ruler. His tribe numbers not more than 30 families, . . . he has listened to the voice of his council; he has encouraged industry, morality and temperance, and discouraged too much intercourse with the whites, . . . Scomiak succeeded Frazier in the chieftainship, not by right of descent, but by appointment of Sir James Douglas . . . who recognized in the young Indian the qualities of honesty, sobriety and self-reliance”.

On the morning of his death, 300 blankets were distributed at a potlatch and three thousand more blankets and a considerable sum of money were reserved for the traditional one-year memorial potlatch.

The funeral procession of Squameyuqs began at his home, near the west side of the Johnson Street bridge to St Andrew’s Roman Catholic cathedral, and then to Ross Bay cemetery where he was buried. Squameyuqs’s wife Mary (1836-1904) was later buried next to him, as well as his nephew Alex Peter who was the chief of the Songhees from 1935 to 1942.