1974.

By Grant Keddie

When undertaking the analysis of the organizational and symbolic content of rock art one would assume that the first step would be to base such studies on a locally derived ethnographic model.

Such is often not the case as one still reads statements to the effect that rock art cannot be interpreted as it is the product of some individual psychic experience. If one takes the time to read the existing literature it is clear that most rock art representation is a product of specific kinds of social conditioning.

The imagery of the art is not a random factor but a culturally controlled and cultivated phenomena. Among the Interior Salish spirit identity and the power, which a spirit gave, were associated with visible fabricated objects. Some of these in a three-dimensional object form and others in a two dimensional “art” on object

form. The main social purpose of these objects is to provide a visual social confirmation that the maker or possessor has been empowered through a vision experience and is therefore deserving of a particular social role.

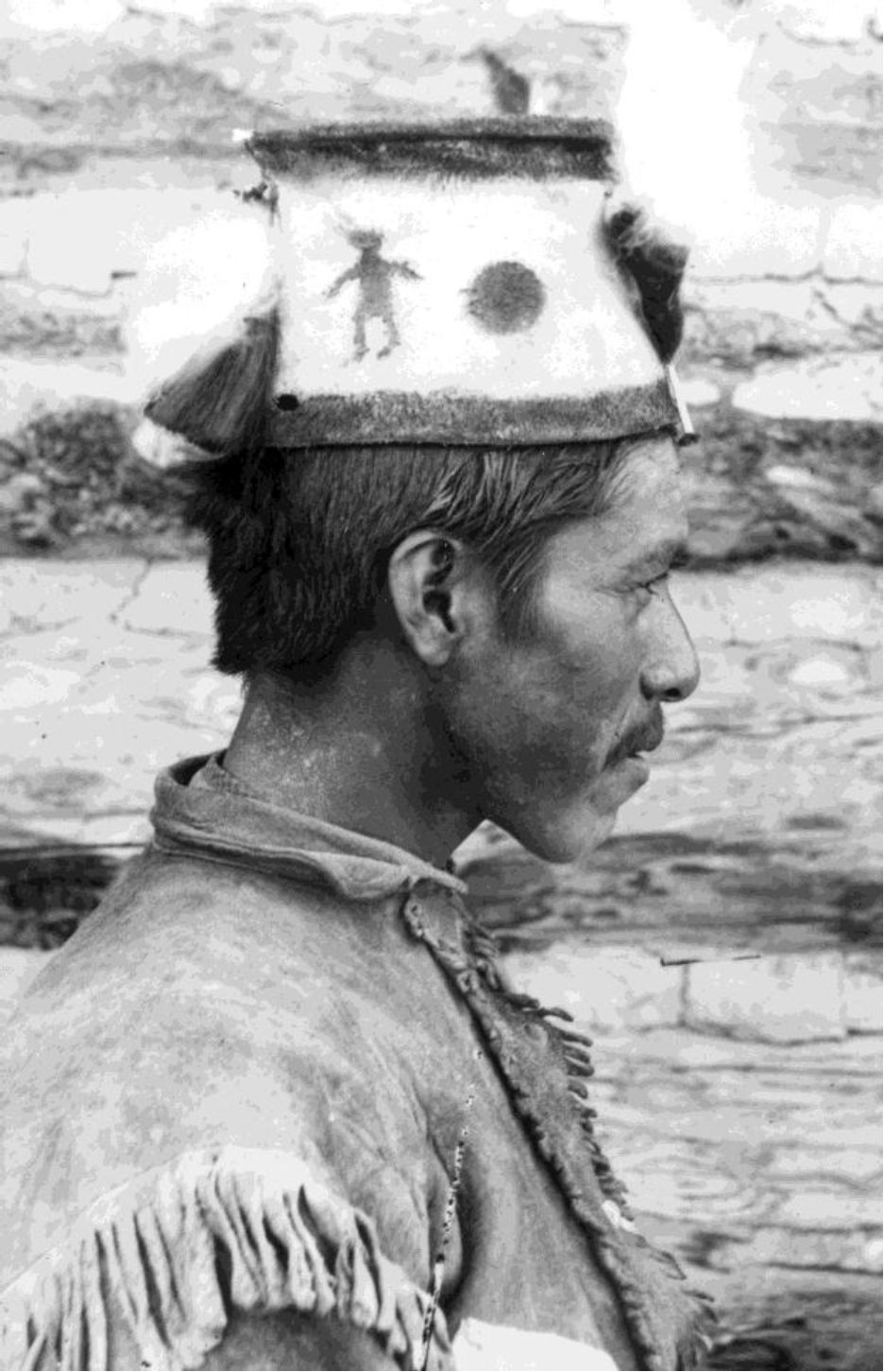

James Teit (1900:381; Fig. 304) shows and explains the meaning of figures represented on a “shaman’s head-band” or hat: “On one side the wolf and a star are shown, and on the other a star and the shaman himself wearing a feather headdress”. There is a drawing of the hat in Teit (1900:215; fig. 183) but not showing the figures discussed. This photograph, taken by Harlin I. Smith, shows the same hat being modeled with the star and shaman on one side. RBCM PN6794.

What I am concerned with here is providing an overview of the social experience that leads to predictability in the patterning of archaeological representations of past events. This will help contribute to providing a framework for interpreting the meaning of at least some of the archaeologically visible symbols and a general understanding of most of them.

Acquiring Power: Why and How?

By undertaking a number of ceremonial activities, which included various combinations of prayer, physical labour and fasting, a person (often at the time of puberty) acquires spiritual powers that were believed to help them through life. The spirit became a medium imparting the seeker with power, magic and knowledge concerning the world of the living and the world of the dead (Teit 1900:320). It was necessary to acquire these in order to insure success, health and protection in one’s life.

After receiving one or more guardian spirits a person painted their face and other objects with designs symbolic of these spirits or symbolic of the ceremonial activities undertaken to acquire the powers. It was these representations which provided the evidence that a person went through the prescribed procedures to acquire spiritual assistance. Some designs were carved or painted on artifacts and clothing. Others were painted on small stones, large boulders, or cave and cliff faces (see Figure 1).

It was objects connected with ceremonies such as the sweathouse, the stones of the sweathouse and fir branches that were often represented in paintings or tattoos.

Symbols were commonly of large animals, birds, arrows, lakes, the sun and thunder or represent objects believed to be of a mysterious nature seen during the training ceremonies, such as mountains or stars. Other spirit representations were symbols of ones desires prayed for during ceremonies. In tattooing, girls would mark “figures of men on their arms to help them to secure a good husband” (Teit 1930:406-407). In a man’s painting a woman symbolized their future wife (Teit 1900:321).

Red paint was considered “as an offering to the spirits” (Teit 1900:344). It was believed that the making of rock paintings itself insured long life (Teit 1900:321).

A youth that wanted the power to “make the arm tireless and the hand dexterous in making stone implements of any kind” would make round pecked holes in rocks or in boulders. “Every night he worked at these until the holes were two or three inches deep. When making them he prayed ‘May I have strength of arm; may my arm never get tired from thee, O stone!” (Teit 1900:320).

Expectations in Acquiring Power:

Acquiring a spirit power was usually not an accidental happening. It was a planned social event with a history of related experience behind it. A young Shuswap or Lillooet person is often sent to seek a definite power, which is some cases, is hereditary (Ray 1942:235-236). Among the Okanagan even children’s names were “generally taken from, or had reference to”, their fathers spirit power (Hill-Tout in Maude 1978:133).

A parent or an old man would give a young person, during a puberty quest, a symbol in the form of animal parts representing the spirit sought. These would be kept throughout life wrapped in a bag with other objects or worn as part of one’s clothing, a neckband, or tied to their hair. Often a boy would dream about this object after having received it. The object would then become one of his guardian spirits. Fathers would sometimes interpret their sons dream and would give advice in regard to them (Teit 1900:219,320; 381; Ray 1942:127, 234, 236, 239).

Spirits Acquired and the Role of “Old One”.

Crucial to the understanding of the spirit powers represented in drawings is the understanding of the personage known as “Old One”. It was “old One” (known by the names Spelkamu’lax and Semo ‘mp’) and also known as the “Chief of the dead” who travelled over the earth “making everything right” by advising the Indians to perform spirit power acquiring ceremonies (Teit 1909:604; 612). Important here were specifically the dances performed at the midsummer and midwinter solstices.

In Shuswap tradition it was “Old One” who instructed the powerful spirits such as Swalu’s (Spirit of the sweat house), Water and Fir Tree to be the guardians of those persons who constantly sought them. It was these spirits that gave individual’s health, wealth, wisdom or success in hunting (Teit 1909:642-3).

In the story of Old One and the Sweat House, Old One visited the Fir-tree and said to him “When may children take your branches and wash with them, may your mysterious power help them…For this reason the Indians use fir-branches,” (Teit 1909:643).

It was Old One who taught people “to fell trees, make twine, sew clothes, make needles and awls, hunt game, trap, dig roots and gather berries: and thus the condition of the people was much improved (Teit 1909:747).

Tradition relates how Old One travelled to six different lands looking for his son who had died, “at last he went to the only remaining one, the land of the dead, where he found his son…Some say that he remained there and became the chief of the dead. Others assert that he returned to the Upper World.” (Teit 1909:748).

The mixing of Christian tradition with a traditional sun deity may have resulted in some of the stories regarding “Old One” or “Ancient One”. In a later publication Teit describes “Old One” or “Ancient One”: “When he travelled on earth he assumed the form of a venerable-looking old man. Some people say he was light skinned and had a long white beard. This deity was also called ‘Chief’, ‘Chief Above’, ‘Great Chief’ and ‘Mystery Above’. According to some, the power of the ‘Great Mystery’ was everywhere and pervaded everything … it was believed that he lived in the upper world or in the sun.” (Teit 1928:289).

“The beings who inhabited the world during the mythological age, until the time of the transformers, were called Speta’ kl. They were men with animal characteristics. They were gifted in magic; …they were finally transformed into real animals. The greatest of these transformers was the Old Coyote, who it is said, was sent by the ‘Old One’ to put the world in order” (Teit 1900:337).

Teit believed that “Old One seems to have been somewhat superseded by Coyote in later mythological tradition (Teit 1909). An important distinction may lie in the belief that Old One did not teach the people how to catch salmon “for there were none of these in the Shuswap country: the Coyote introduced them at a later date, and taught the people how to fish for them” (Teit 1909:747).

Patterning of Guardian Spirits Activities and Spirits Represented in Paintings

Since guardian spirits could be represented by almost any animal, insect, plant, inanimate objects such as rocks or lakes, heavenly bodies or natural phenomena such as thunder or fire, there may seem to be almost limitless possibilities for pictographic representation. However cultural selection plays a role in giving preference to specific sets of spirit representations and it can be expected that these are visible on a regional basis.

Since like spirits do not always convey like power the visual patterns in the archaeological pictographic record will not necessarily reflect the same kind of power but could be a reflection of the same kind of spirit. And it is these spirit patterns that one may look for on the landscape.

In the case of animal representations the power is reflective of the character of the animal (Ray 1942:235). Certain images may be reflective of specific powers such as “fleet footedness” and others of general powers such as hunting and fishing powers or specific sets of spirits, which may reflect shamanistic powers.

Certain spirits could be considered akin to tribal deities. The most obvious was the Dawn of the Day spirit. Every morning one of the oldest members of each household went out of the house at the break of day and prayed to the Dawn (Teit 1900:344).

Specific groups such as hunters prayed to other general classes of spirits in addition to guardian spirits. Adolescents prayed mainly to the Day Dawn, and many warriors prayed principally to the sun. Everyone made prayers or offerings to named deities or powers inhabiting specific localities. (Teit 1030:291).

Girls Puberty Ceremony and Fir Bough

When a young girl was isolated in the woods at puberty she prayed to the Dawn of the Day each morning (Teit 1900:313). During her training period, however, prayers were “generally addressed to the fir-branch” (Teit 1900:315). The girls “rubbed their bodies with fir boughs when bathing to make themselves strong”. This use of the fir branch ceremony was the same among the Similkameen, Okanagon and Thompson (Teit 1930:282).

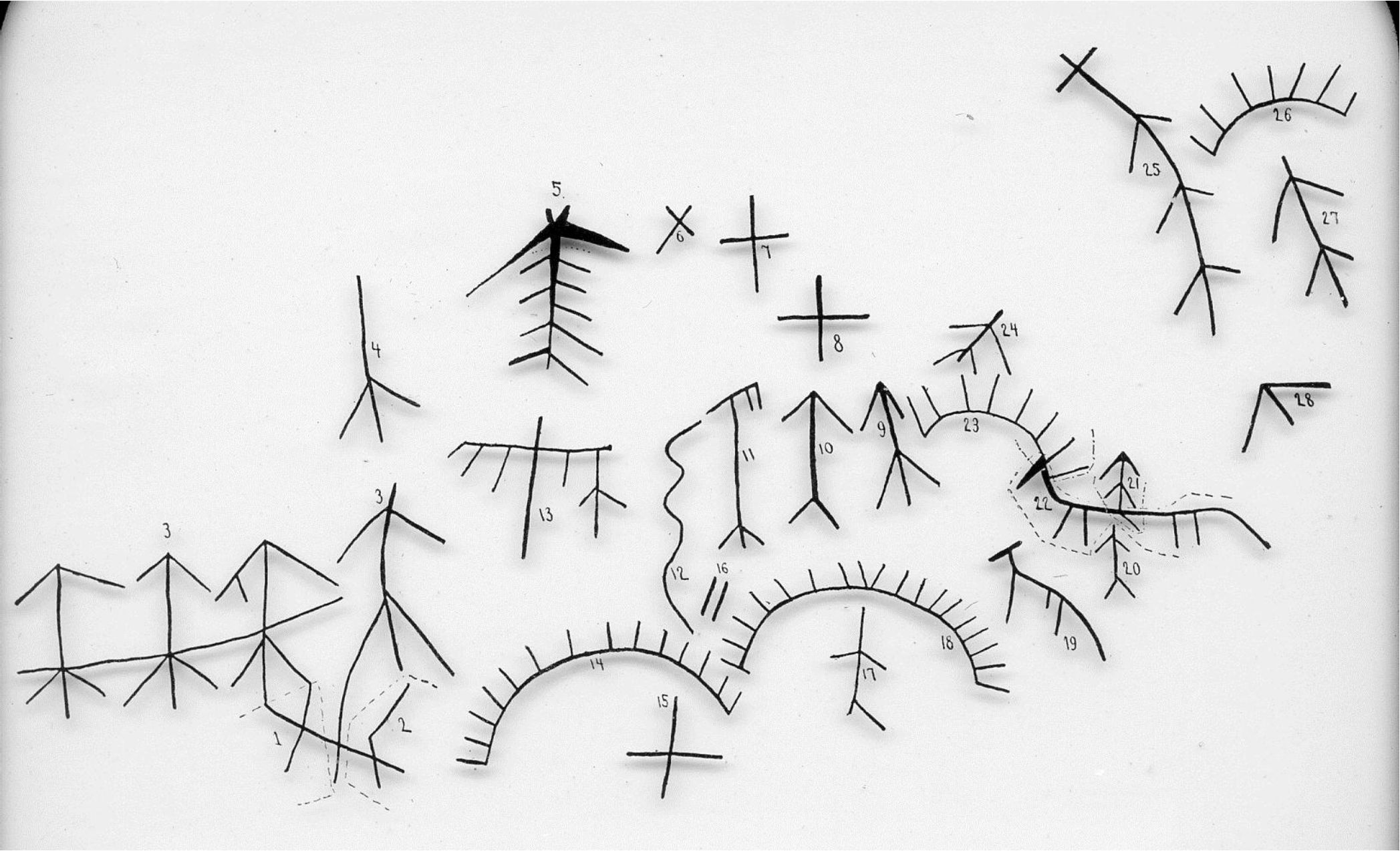

“A girl made a record of her offerings, and the ceremonies she had passed through, by painting pictures of them with red paint on boulders and on small stones placed at the ends of a trench she was expected to dig near a trail. This was intended to make her capable of doing hard work and insure her long life, but being near a trail they were meant to be seen as a confirmation of her experience.

The pictures were generally all of the same character, and consisted of such things as fir branches, cross-trails, lodges, mats and men. These paintings were undertaken toward the end of her period of training” (see examples in Figure 2). The pictures of men, she painted were symbolic of her future husband. (Teit 1900:317). The girl also planted at the end of the trench a single fir-branch and wiped her eyes and her face with small fir-branches, to make herself good looking, … After the ceremony the fir branches were hung on the branches of a tree.”(Teit 1900:313).

Painting On A Boulder Near Spence’s Bridge.

1,2,6,7,8,15 Crossings of trails; 3,4,9,10,17,21,24,27,28 Fir-branches; 5,Girl’s lodge, and fir-branches hanging down from roof; 11, Roof of girl’s lodge with fir-branches handing down; 12, snake; 13, Sacrifices put up at crossing of trails; 14,18,23,26, Unfinished basketry; 16, Two trenches; 19,22 Dog (After Teit, 1900, Plate XIX, Figure 1).

References

Maud, Ralph (Editor). 1978. The Salish People. The Local Contribution of Charles Hill-Tout. Vol. I: The Thompson and the Okanagan, Talon Books, Vancouver, B.C.

Ray, Verne F. 1942. Culture Element Distributions: XXII. Plateau. Anthropological Records, Vol. 8, No.2, University of California.

Teit, James. 1900. The Thompson Indians of British Columbia, Vol. 1, Part IV, The Jesup North Pacific Expedition. Edited by Franz Boas. Memoir of the American Museum of Natural History, New York.

Teit, James. 1909. The Shuswap, Vol. I, Part VII. The Jesup North Pacific Expedition. Edited by Franz Boas. Memoir of the American Museum of Natural History, New York.

Teit, James. 1906. The Lillooet Indians, Vol. II, Part V, The Jesup North Pacific Expedition. Edited by Franz Boas. Memoir of the American Museum of Natural History, New York.

Teit, James. 1930. The Salishan Tribes of the Western Plateaus. Edited by Franz Boas. FortyFifth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology. To the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1927-1928, United States, Government Printing Office, Washington.