Originally published in Discovery, 19(1).

Winter 1991.

By Grant Keddie

One of the most fascinating places to visit on southern Vancouver Island is Harling Point in the Victoria municipality of Oak Bay between Gonzales Bay and McNeill Bay.

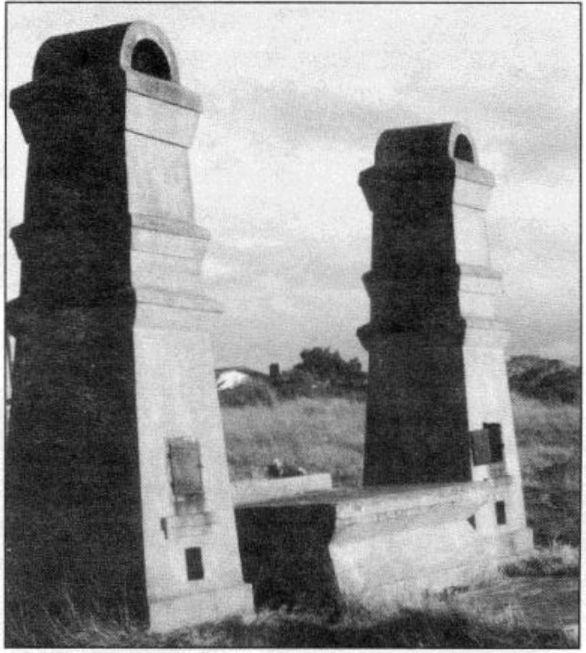

Many people go to Harling Point to see the Chinese cemetery. You can walk up to the large concrete cremation pillars and altar and see where, in the early 1900s, relatives placed food and burned colourful rice-paper offerings for the dead.

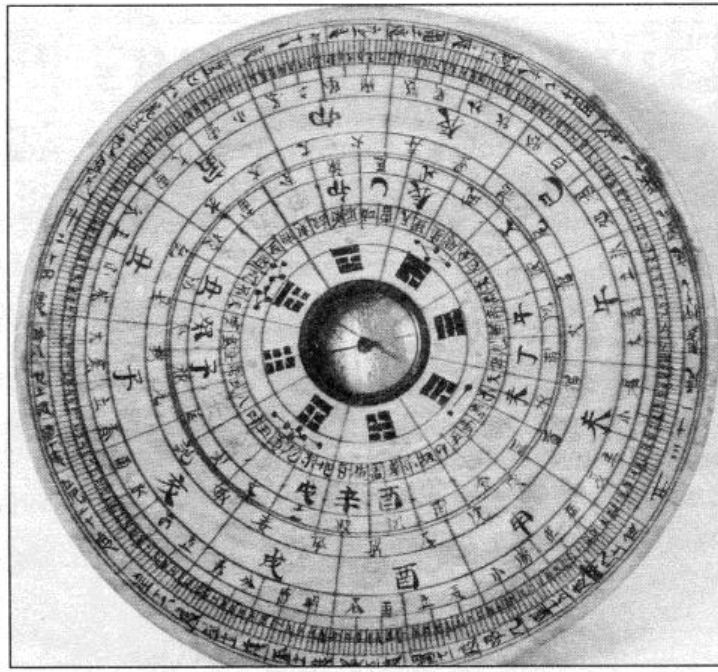

The Chinese traditionally choose locations for important cultural activities, such as burials, that are in harmony with nature by following the practice of feng-shui. In Western terms, this is geomancy, the selection of particular sites of land whose inherent qualities are such that they will be favourable for a defined purpose; a burial site is one of those purposes. A Chinese master of feng-shui intuitively comprehends and assesses the properties of a site with the use of a highly sophisticated type of magnetic compass.

Other people go to Harling Point to see the tidepools or to sit quietly and watch the Harlequin Ducks, American Black Oystercatchers and Black Turnstones that linger close by.

However, among the other fascinating things to see at Harling Point are the very rocks on which you walk – they form one of the most unique geological sites on Vancouver Island. There you can see where two ancient continents met, and the fault contact zone caused by their meeting.

Three hundred million years ago the ancient continent of Wrangeilia formed as one of Earth’s crustal plates near where the equator is today. Over millennia, this large plate slowly shifted to eventually become part of the coastal mountains of North America, including the Wrangell mountains of Alaska, the Queen Charlotte Islands, part of the southwestern coast of British Columbia, and Vancouver Island.

The southern tip of this ancient continent now lies at Harling Point where it collided, 40 million years ago, with part of another ancient continent now referred to as the Leech River terrane.

Because of this, you can do something truly unique at Harling Point: you can put one foot (on the seaward side) on some beautiful beds of pale green ribbon chert, and the other foot (inland) on the much darker basalt rocks. And when you do, you will literally be standing on two ancient continents!

Among the native Songhees people, whose territory encompassed much of the Greater Victoria region, there is a tradition that everything was created by a spirit-being named “Hayls”. There are only two recorded locations where Hayls performed his acts of creation – and one was at Harling Point.

In 1952, anthropologist Wilson Duff recorded the story of Harling Point from an elderly Songhees named Jimmy Fraser. He was the grandson of Chee-al-thluc, or “King Freezy”, who was recognized as the highest-ranking chief when Fort Victoria was established in 1843.

According to Fraser, the name for Harling Point is Sahsima, which means “Harpoon”. Fraser also told how Hayls “came around with his companions, Raven and Mink, to teach people how to lead proper lives. Two men harpooning seals off the point were disturbed by the visitors. The harpooner rebuked them for frightening a seal he had been stalking. Hayls turned him to stone, standing poised to throw the harpoon, and made him the boss over the seals”.

Fraser went on to say: “When the white men came they cut up the rock for gravestones, and that is why there are so few seals left.” This last part of the story was likely a message for the non-Indian. In fact, there is no evidence of rocks being cut in this area.

The story may refer to large boulders that can still be seen on the beach. We know from other localities that native people had traditional stories referring to such large isolated boulders, which we call “Glacial erratics”. Glacial erratics are boulders, usually of a different kind of rock than the surrounding bedrock, that have been dragged along by glaciers and eventually dumped, when the ice melted, far from their points of origin.

The message of Sahsima is to respect the balance of nature. Perhaps we still have much to learn from this very special place called Harling Point.