Originally published in Discovery, 1993:3.

Summer 1993.

By Grant Keddie

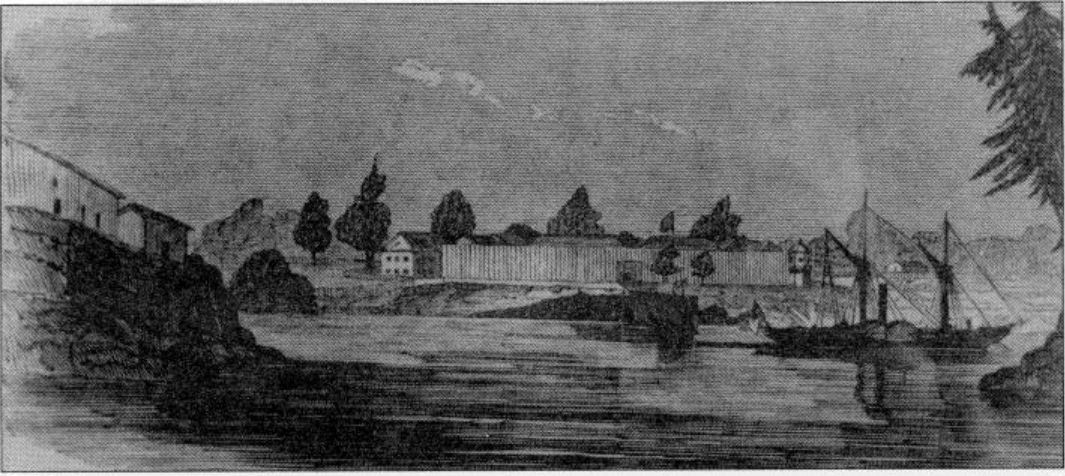

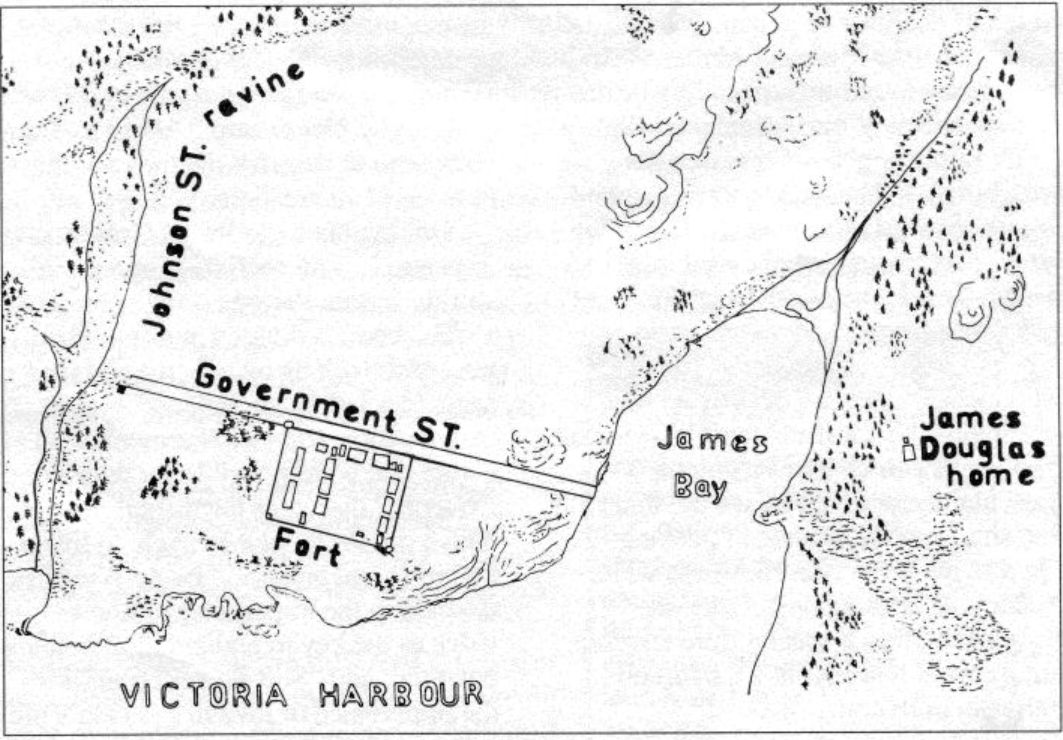

In April 1843, native people were hired to cut posts for the walls of the first nonnative buildings on the southern tip of Vancouver Island: Fort Camosun. They were given a 2’/2-point Hudson’s Bay blanket for every 40 posts, each measuring 3 feet in diameter by 22 feet long (1×7 m). On I June, about 40 men and 3 officers from the Hudson’s Bay Company began building the fort.

The fort was initially referred to as Fort Camosun, and then between 6 August and 4 December as Fort Albert, in spite of an official letter dated 14 April from the Hudson’s Bay Company, which refers to the general location as: “named Camooson, by the natives, and which we have named Fort Victoria”. On 18 December the logbook of the Hudson’s Bay ship, the Cadboro, makes the first written reference to Fort Victoria. Camosun Harbour.

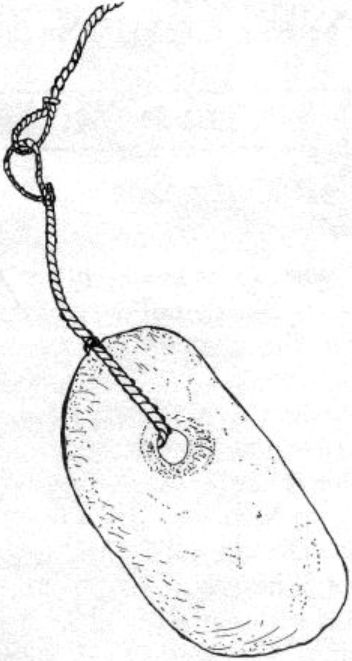

The native name for this area was documented by Joseph MacKay, who was fluent in the local language and knowledgeable about native traditions. In a letter to Government House in 1894, he said, “…the Indian name for the original site of the city of Victoria is Kuo-sing-el- as, the root of the word being the name of a species of Willow which grew in abundance on the ground, the inner bark of which was inset to fasten the stone sinkers to their fishing nets and hooks.” Today, we call this tree Pacific Willow, or by its scientific name, Salix lasiandra.

Before the city grew over it, the area of downtown Victoria east of the harbour was an open glade of oak trees and swampy areas above a rocky shoreline. A creek ran from a swamp near the present junction of View and Quadra streets to a ravine just south of Johnson Street. A forest of Douglas-fir grew along the ravine. Another creek, draining the Fairfield area, emptied into James Bay, near the present comer of Blanchard and Belleville streets.

This wilderness provided native fishermen with the raw materials for many tools, the bark of the Pacific Willow among them. McKay explained this in another manuscript: “They made twine for fishing lines and nets from the fibre of a species of native nettle, a plant commonly known as the fireweed, and from the fibre of the inner bark of the red and yellow cedars. The long flexible stem of the common kelp

was also used for fishing lines; the inner bark of the willow was used for strapping stones for sinkers in deep-sea fishing. Some willows yielded a stronger and much more pliable fibre than others; the present site of Victoria, particularly that portion between Wharf and Douglas streets and [near] the junction of Cook Street and Belcher Street [now Rockland], yielded a willow with very strong fibre, hence the Indian name for the city of Victoria is Ku-sing-ay-las. meaning the place of the strong fibre.”

Over time the local trees were cut down and the swamps and ravines filled. Today all that remains of the original landscape is a few rock outcrops along the harbour.