Originally Published in Archaeology of Coastal British Columbia: Essays in Honour of Professor Philip M. Hobler. SFU Archaeology Press.

2003.

By Grant Keddie

Introduction

One morning in the spring of 1969, I went with my field-school professor, Phil Hobler, to rediscover the Bella Coola village of Anutcix (FaSu 10) near the mouth of the Kwatna River. When we located the site and its distinct shell mound features, Phil commented on how each site is different and can tell us different things. His teaching style was to have us ask questions rather than just listen to answers. When I found the first donut stone, Phil asked me to look at the evidence and tell him what it was. Today when I look at an archaeological site I ask why is this site at this particular location? When I look at an artifact I consider the evidence it presents first, and then at the classification in the text book.

Over the years I have observed the evidence on stone figures, bowls, and combinations of these. Although many individuals such as Wingert (1952), Duff (1956; 1975), Carlson (1983c, 1993, 1999) and Hanna (1996) have presented information on this subject, there are numerous specimens in private and museum collections that have yet to be included in any study. I intend here to add a few observations and a few new pieces to this varied and complex subject.

Seated Figure and Similar Bowls

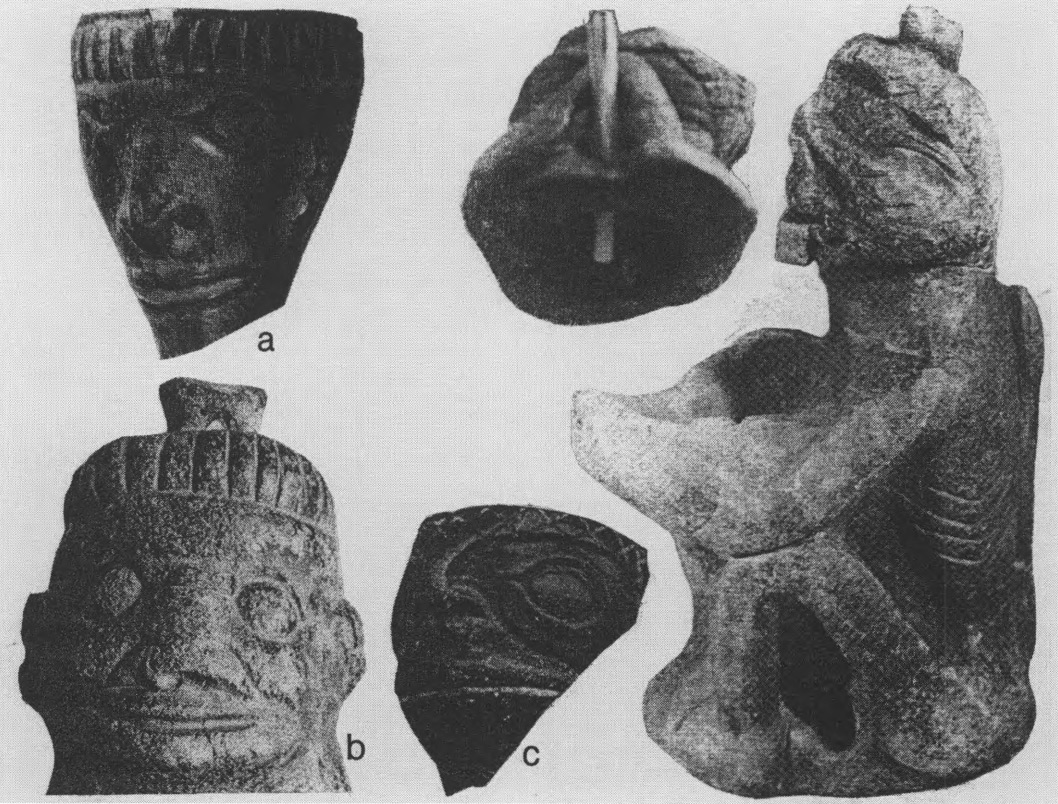

I would agree with previous authors that the seated human figure bowls are primarily associated with shamanistic rituals. They are containers of power related to the interaction between humans and the spirit world. For example, Figure 12:1 from the lower Columbia River has a protruding tongue, wears a crown, and holds a rattle, all attributes associated with shamanism.

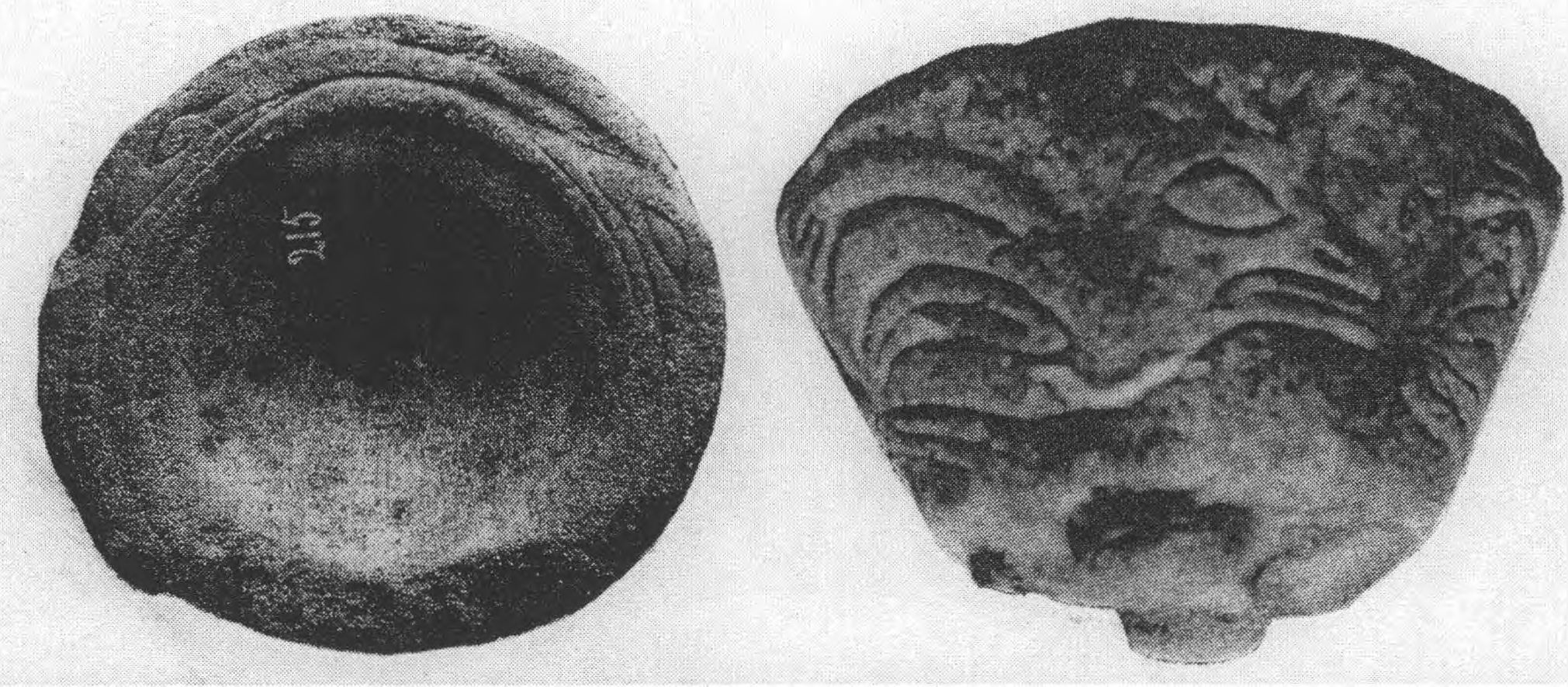

Owls, known for their strong association with shamans, are by far the most common identified birds on bowls (Figure 12:2). For example, this bowl (Figure 12:3a) from the lower Fraser River may represent an owl-human. The Lummi believe that owls have close communication with the dead and often posses the souls of the dead (Stem, 1934:81). A Saanich man, Tom Paul, said that the “saila” inside a person is the soul of an animal that has visited them in a dream. The soul becomes the “Big Owl”. The shadow of a person becomes the small owl, “spalkwithe”. When this owl flies through the roof of a big house it is there to talk to a medicine man or “thetha” (Jenness c. 1934-36).

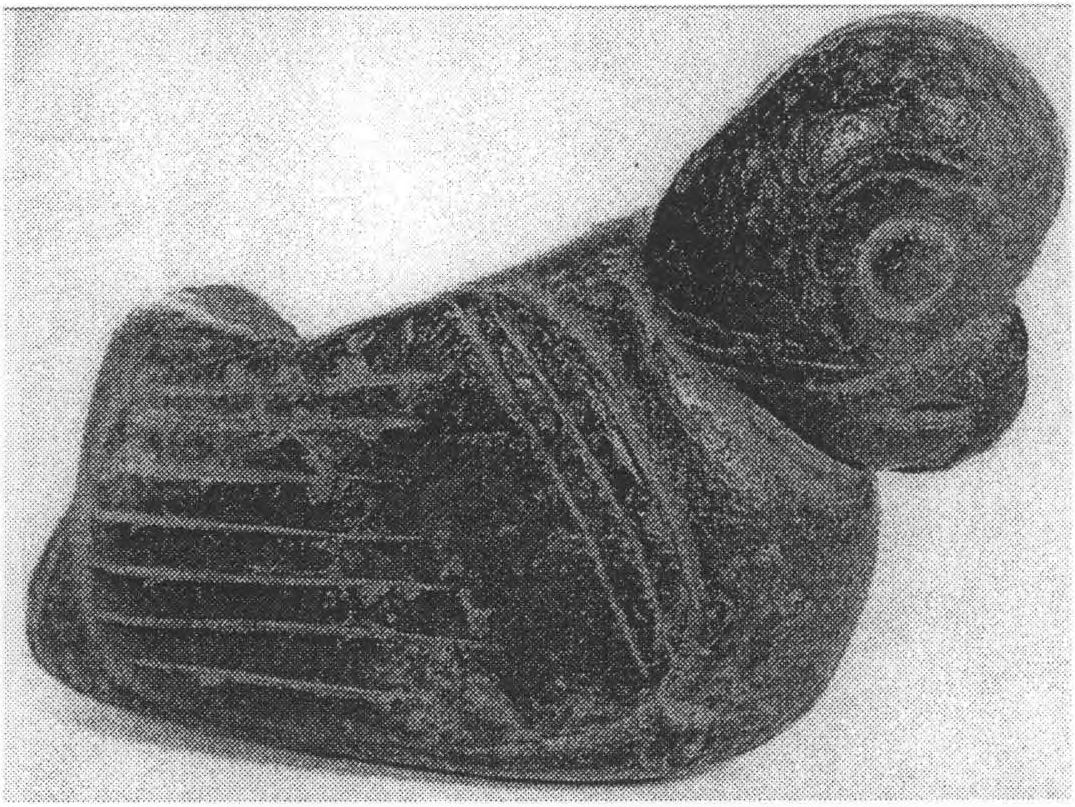

Many stone figures not reported in the literature to date show similarities to those already described, but others are quite different. A unique human figure bowl (Figure 12:3b) stands in contrast to many others. It is a detailed human figure holding a bowl made of vesicular basalt, but other than the ribs, lacks the iconography usually found on either the bowl or the human. This realistic image clearly represents a fully kneeling human with a distinct round bowl on its lap. This extreme undernourished look, does, however, occur on some smaller figures with larger heads and can be seen here carved into this antler harpoon base (Figure 12:5). These extreme forms are more like later representations seen on wooden carvings on the northern Northwest Coast.

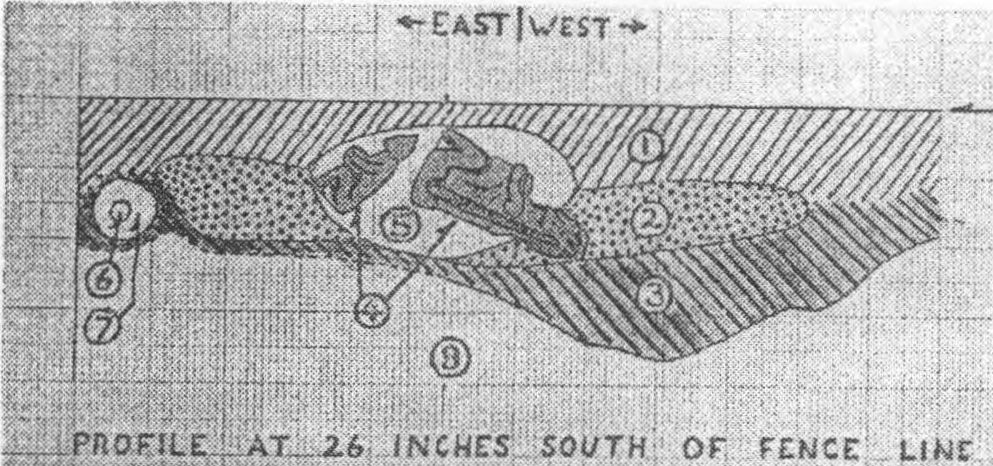

There are three examples of seated human figurine bowls from southern Vancouver Island that were ritually buried without human remains. One bowl (DcRw2:l) was found associated with a rock pile when a large tree was uprooted 30 meters beyond a shell midden on a high bluff above Whiffin Spit in Sooke. Two human seated figure bowls were found together in a cremation pit above the Gorge waterway in south Saanich. These bowls were likely viewed as powerful objects belonging to a deceased shaman that needed to be ritually burned and disposed of away from any village. After they were dug up in a rose garden Don Abbott and John Sendy were shown exactly where they were found, and they then excavated a larger area, which included an intact cremation pit with ash lenses (Figure 12:5).

Some stone figures have attachment holes on their head or back that were probably for tying to a fixed post or wooden structure. One of the cremation pit bowls has a hollow base and two holes extending from the outside base into the hollow (Figures 12:6). This specimen, like a number of the smaller specimens, was clearly designed to fit onto, or to be pinned into a wooden post or scepter.

Analogs are known from northern China where a picture of Kuvera, known in Hindu mythology as the god of wealth is shown with a stone figure attached to his staff. Kuvera was also worshipped by Buddhists as one of the guardians of the center of the universe and the regent of the north. He is represented with snakes coming from both sides of his head and wrapped around other parts of his body. Fastened to the end of his scepter is Nakula, the Mongoose (Getty 1928:148c).

Pipes and Bowls

Borden (1983:157, Figure 8:29a) pointed out the stylistic similarity between human effigy pipes dating after 200 A.D. in the Fraser River Canyon and the more finely worked stone human sculptures. Carlson (1983c:201), linking a Saanich pipe bowl with a snake motif and the seated figure bowls, concluded that the more finely developed human stone bowl figures were actually tobacco mortars used in conjunction with pipes in the same style, and that both were employed in shamanic curing rituals involving smoking.

In further examining this question I observed all of the stone pipes in the Royal B.C. Museum collections and those represented in photographs from private collections. It became clear that there are distinct and detailed similarities between Interior pipes and Coastal bowls such as in the features of a pipe bowl face from Lytton (Figure 12:7a) and the face of a human figure bowl from near Courtenay on Vancouver Island (Figure 12:7b).

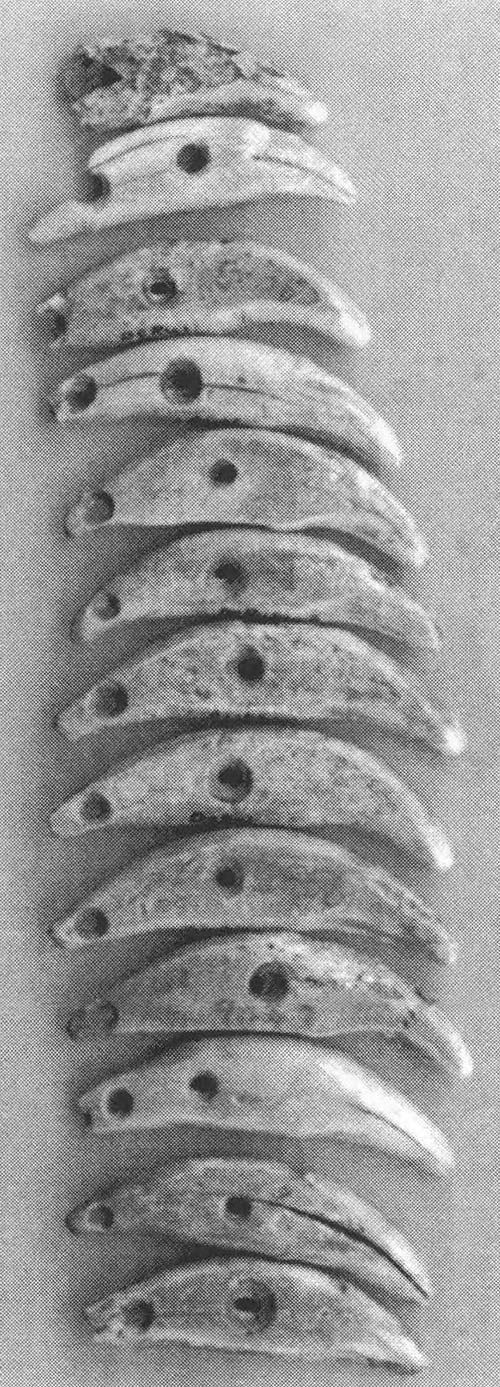

The common headpiece on these figures is probably the shaman’s crown of bear claws, mountain goat horns, or teeth. Examples of teeth with double drill holes that were joined in rows (with spacers) have been found in archaeological sites on the southern coast. This set of dog teeth (Figure 12:8) was found by Robert Kidd and Michael Kew in 1959, associated with a burial at the Blue Heron Lagoon site on the Saanich Peninsula. A cluster of 6 small leaf-shaped stemmed points (DeRu 1:24,23-2428) was also included.

My examination of the provenance of stone pipe fragments at coastal sites also supports Carlson’s contention of a time association of pipes with later period stone bowls. Steatite pipe fragments are infrequently found on southern Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands. Where they do occur they are found only in sites with components predating 1600 years ago.

The precise dating of trumpet-shaped tubular stone pipes in the Fraser Canyon can only be placed with certainty after about 500 A.D. in the Canyon cultural type (Mitchell 1990). This time corresponds with the introduction of clay and stone pipes among the Late Marine cultures of coastal Oregon (Pettigrew 1990). The evidence suggests that pipes, made with interior raw materials, occurred first on the Coast and were not used in the southern Interior until around 1200 A.D. The fact that they occur much earlier on the lower Columbia River suggests this is a topic much in need of further cross-border research.

Snake Representations

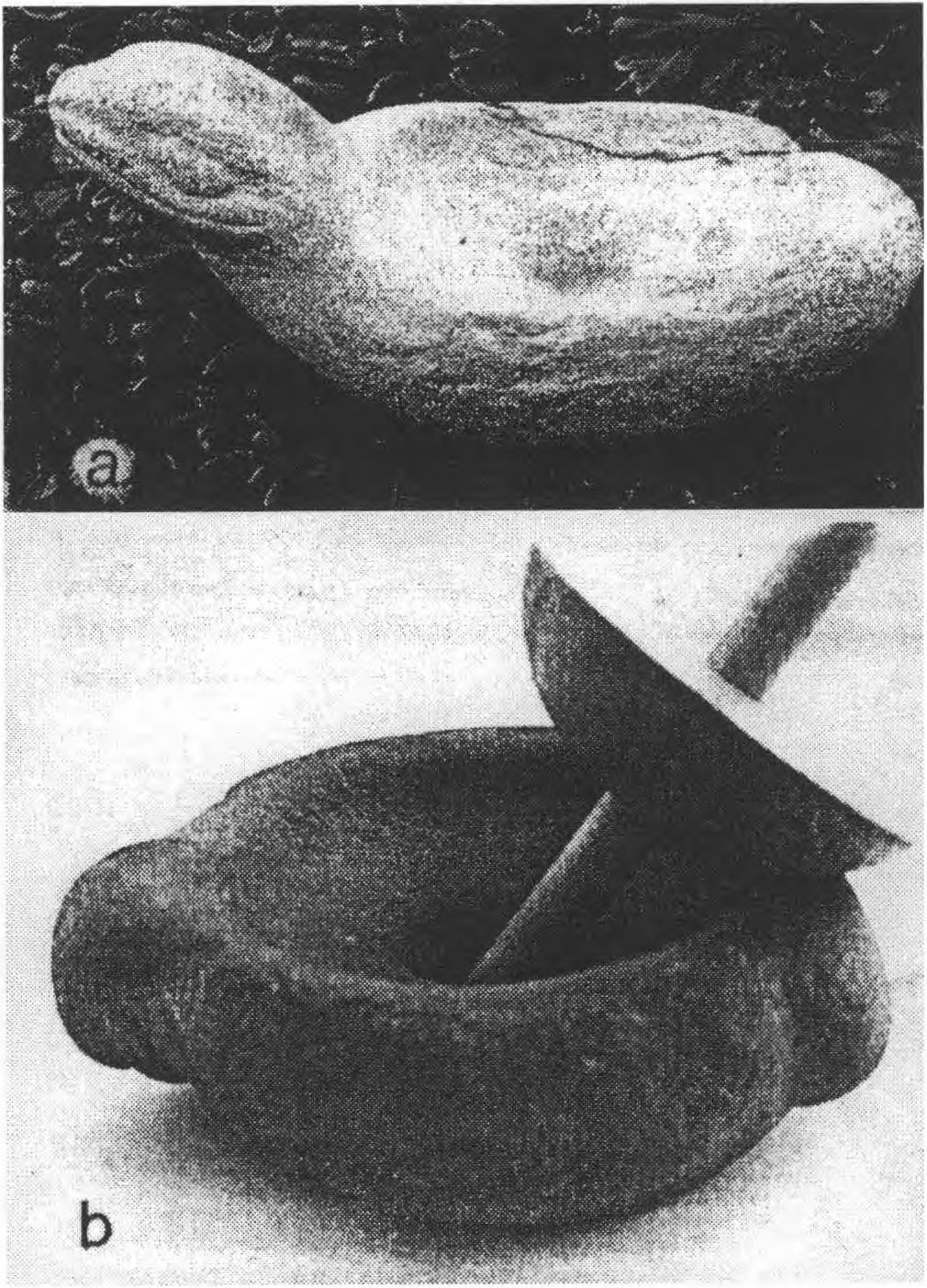

Snakes are the most common animals incorporated into the seated human figure bowls, and often occur on both sides of the human head (Figure 12:9a). Most of these motifs do not seem to represent supernatural snakes but realistic rattlesnakes1. Some bowls are snakes in themselves. A very small bowl from the Hope area represents a coiled rattlesnake (Figure 12:9b), as does a larger specimen (Figure 12:9c) from the Bazan Bay site in Saanich, where several human figure bowls have also been found. Snakes are also found on tubular pipes (Figure 12:7c).

Boas (1891:577) was told that on the lower Fraser River: “Rattlesnake poison is obtained by trade from the tribes on the Fraser and Thompson rivers. A powder of human bones is drunk as an antidote”. Consuming dry snake venom is just as poisonous as being bitten by a rattlesnake. Although this traded poison may have been used for war arrows, it is also possible the dried snake venom was placed in these bowls and used in very small doses as a hallucinogen or in larger doses to poison enemies. Or possibly very small amounts of dried venom were mixed and smoked with tobacco.

There is a belief in the curative value of snake parts. Harmon noted that Carrier women, at the time of delivery “drink water in which the rattle of a rattlesnake has been boiled” (Lamb 1957:218). Duff (1956:27) noted the label on the Yale Bowl at the Vancouver Museum said: “The Indians say the bowl was filled with poison and was placed on or near a body laid out for burial, so that wild animals might drink the poison.”

The rattlesnake is also represented in small ornaments (Figure 12:10), although my examination of some previously described as ornaments clearly shows by the nature of the slightly rounded and ground bases, that they were used as pestles possibly to grind tobacco in the bowls. An examination of larger wood-working hand mauls in the Royal B.C. Museum collection that have rattlesnake-tail motifs, places these – like stone pipes – in the first few centuries A.D.

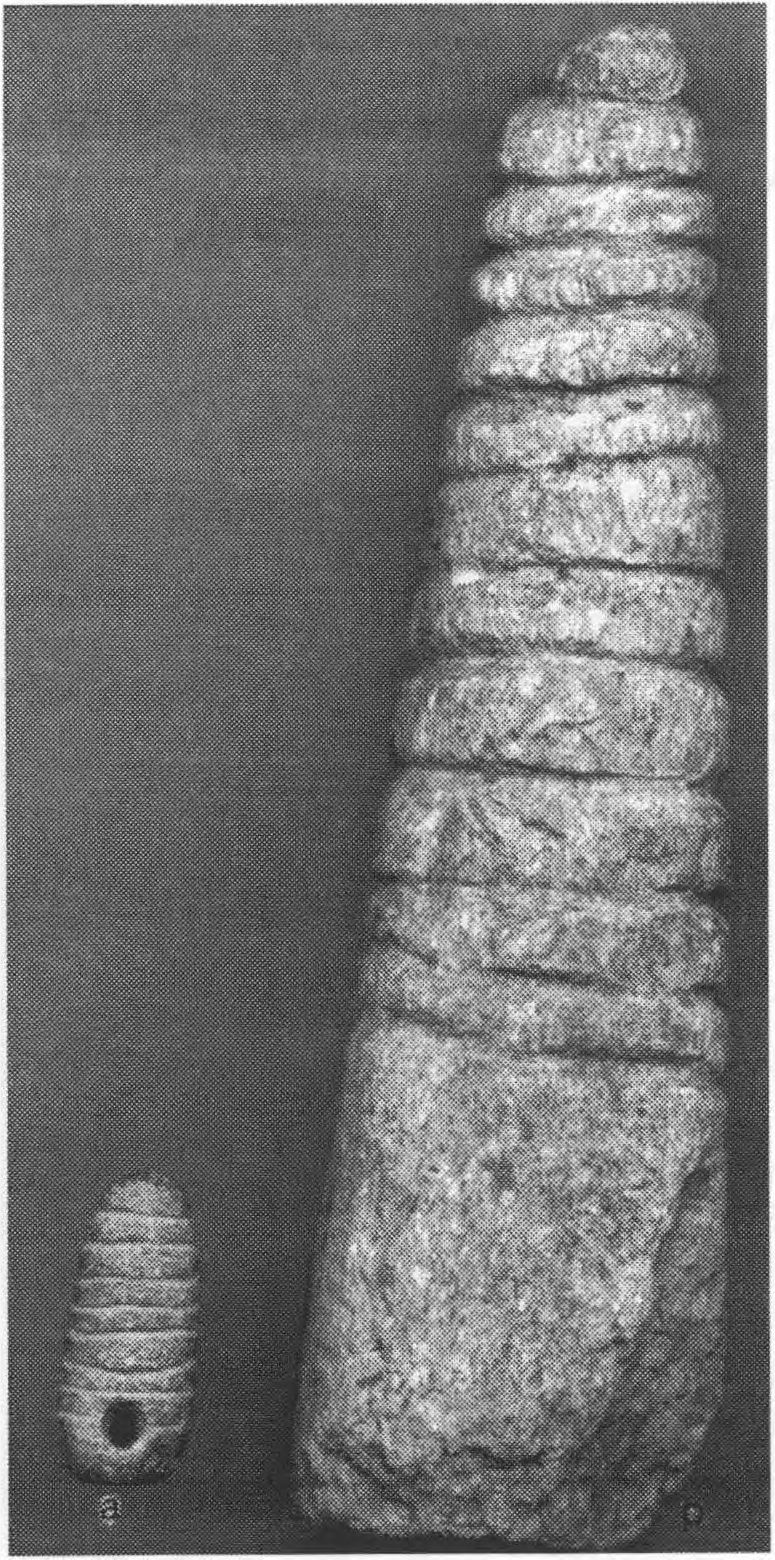

Spindle Bowls

One later type of bowl may have come into use with the introduction of spinning. I would suggest that some small bowls, especially those with depressions in the bowl part (Figure 12:11a), were spinning bowls used with a sustained spindle. A sustained spindle is a type that revolves on a surface. This way of spinning is the more common type practicedin the Americas, parts of Asia, and the Pacific Islands. The control provided by the end of the spindle being in a bowl (Figure 12:11b) allows the spinner to obtain the more even tension critical in spinning, particularly when spinning short fibers.

The type of spinning seen on the Northwest coast in historic times is a rare practice. Depictions of spinning all refer to the spinning of longer wool thread that has already been prespliced by thigh rolling. However, small stone spindles that are more common in archaeological sites may have been used mainly for spinning thin strands of stinging nettle and other plant materials used in making nets and foundation material for wool capes. These may have been used in a different manner than the larger historic spindles.

One bowl (Figure 12:11b) with a depression within its bowl comes from site DcRu 19 in Es- quimalt Harbour. I dated the base of this shell midden site to about A.D. 1310.2 The highly polished and sloping inner hole suggests this bowl may have been used for supporting the bottom of a spindle. The bowl is a bird (possibly an owl) facing down with the bowl in its back.

Another possible weaving bowl (Figure 12:12) is from an unknown site on Mayne or Pender Island 3. It has four protruding legs,, three thunderbird-like motifs around its body, and two snakes encircling its rim similar to those found on some small stone spindle whorls.

Large Human Figures without Bowls

There are many very large stone figures (Figure 12:13a) that were likely used in rituals to control the weather for the purpose of improving fishing conditions, to ensure safety in venturing out in pursuit of food, or to create unsafe conditions for enemies. This top portion of a pillar-like rock was found on the south shore of Pilot Bay (DhRxl7) on Gabriola Island. With its broken off bottom piece, it is over 80 cm high, 30 cm wide, and weighs about 220 lbs. The carved top has a human head with arms held out in front. Its much larger bottom portion is un-carved and was likely planted in the ground.

On the southern coast appeals were often made to beings whose souls were reflected in the winds. Boas was told that at Finlayson Point in Victoria a rock was moved one way to create pleasant weather and in the other direction to create bad weather. Wind rocks were also used by the Klamath Lake people of eastern Oregon (Carlson 1959).

A Songhees named “Joseph” told about a special place where two stone pillars were located near Loon Bay. One rock was a rough block of layered sandstone with one layer forming a rim around the top that looked like a hat. The block was sitting on a glacial boulder and “seen from a distance, may easily be taken for the image of a small boy with a large hat on his head, sitting on a block of stone.” The rock was called Yicsack which means “hat”. Dances were performed around the rock and it was treated with a coating of fish oil. In 1876, the sandstone slab was knocked off by cattle and broken. It was taken to Joseph’s home for protection, but was returned in 1878, when bad weather prevented the Songhees from fishing.

Joseph said that about 1840, when he was a boy there had stood for many years “two square pillars about six feet high, set on end as to form a doorway”. He remembered as a child going with his father on a stormy day to rub Yicsack and the pillars.” The stone was last rubbed in 1880.

Lummi and Semiahmoo people told Suttles that: “At Point Roberts there were two stones in the playground behind the camp. These were painted at the beginning of each fishing season. During the first-salmon rite the boys marched around them, singing” (Suttles, 1974:178-9).

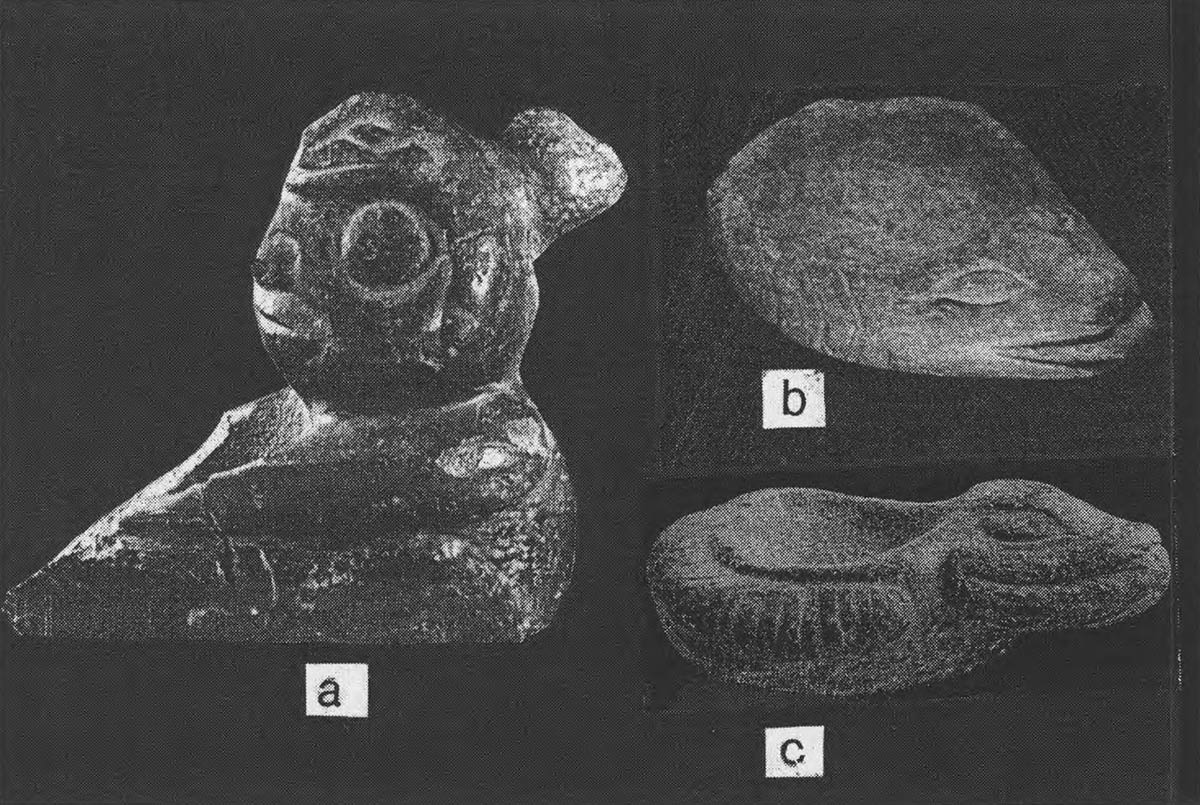

A large, meter high, carved stone (Figure 12:13b,c) was found on the prominent Grief point, south of Powell River opposite the northern tip of Texada Island. The site is a large shell midden associated with fish traps. The stone has a human figure with arms out in front carved above a massive base. The lap area has been extensively rubbed as a result of ritual activity and not as part of its construction. The figure is unique in having an owl-like bird (Figure 12:13c) carved on its chest area similar to the spiritual icons found on the bowl part of Seated human figure bowls.

Fakes

I have observed many fake stone bowls in private collections that are of recent manufacture. Many of these have been brought to the RBCM for the purpose of attempting to sell them. However, one of the larger collections of fakes is the older collection of Ross A. Brooks.

Ross Brooks4 had a great interest in archaeology and ran a shop on Robson Street in Vancouver called “The Old Curiosity Shop”. Brooks had a collection of at least 90 stone figures, mostly stone heads, that he claimed to have collected between 1944 and 1946 from a place on the lower Fraser he named “Brooks Mound”. He would not reveal the site location, but produced detailed excavation notes on the discovery and description of the material. His paper Brooks’s Mound, Frazer River, B.C. Exploration Notes by R.A. Brooks shows his preoccupation with romantic ideas about ancient civilizations, sunken continents and Velikovsky’s comet.

Charles Borden wrote a report titled Brook’s Mounds and Stone Heads in June of 1947. Borden could not make up his mind about the origin of the material, but was swayed by a report from the U.B.C. Geology Department claiming that the weathering and carving were old and not of recent origin. After the death of Ross Brooks, Borden’s recommendations resulted in Dr. H. R. McMillan purchasing the collection for U.B.C. from Brook’s widow,Mabel Orr Brooks, in 1950.

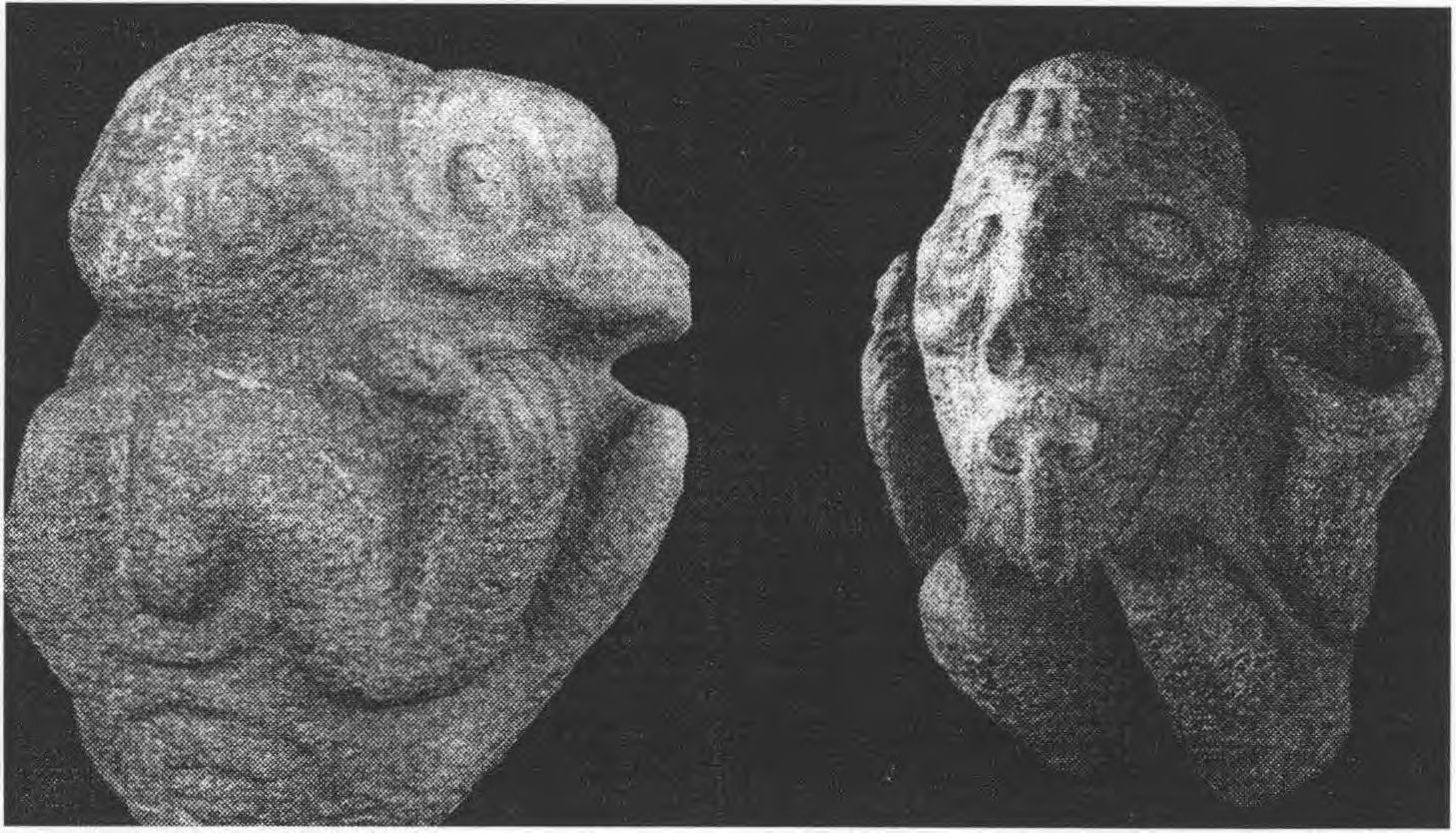

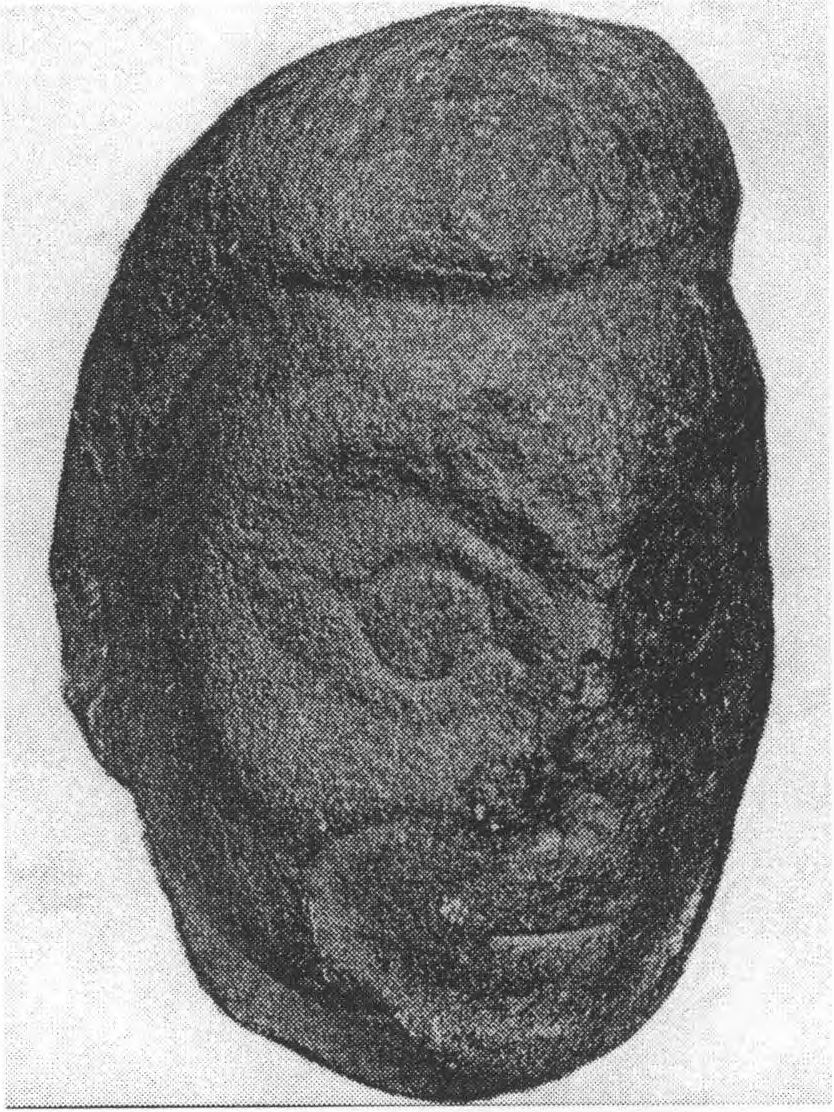

In a 1961 letter, Wilson Duff notes “I am still interested in solving the problem of the location of the Brooks Mound”. He states5, “Only one of the stone heads [Figure 12:14] seems to fit into the archaeology of this area.” I understand that geologists examined the carvings and rejected any idea that they were freshly-made fakes. So the Brooks Heads remain a puzzle. Some day we shall get a clue that will lead us to their place of origin or definitely establish them as fakes.”

I examined the Brooks artifacts and archival collections at U.B.C. in 1987 and undertook further research on the subject including discussions with surviving family members.6 Other than the stone head used by Duff in his publications and a few real, but displaced, non-stone head artifacts in the collection, I am convinced that all the rest are fakes made by Ross Brooks, or in some cases possibly recently made objects purchased in South America. Brooks was strongly influenced by early writing about stone sculptures of Easter Island. The proto-types for some of his sculptures can be seen in Easter Island carvings (see Heyerdahl, 1974, Plates 148154). Brooks used mostly course grained igneous rocks that are easier to treat to produce a fake patina and obscure signs of recent steel tool marks. Some of the stones were coated in tar and buried in the ground or heated in a fire and then cleaned off. Some with tar still on them were likely unfinished fakes that Brooks did not clean before he died. Some items do show steel tool marks and are lacking a patina. A careful reading of the supposed field notes reveals many contradictions. It is clear to me that Brooks faked all of these notes to give credence to his fake stone heads.

Summary

Wayne Suttles noted, that within the continuum of Salish speaking peoples “there were some pretty clear cultural differences, seen especially n the distribution of ceremonial activities”. It is probably safe to assume that this was the case 2000 years ago, whether we are dealing with the ancestors of recent Salish speaking populations either in whole or in a small part.

Whether the two-headed serpent was an important source of vision power in the iconography of 2000 years ago, as it was in the ideology of more recent times among some Salish speaking peoples, cannot be determined. As we can see when we view the powerful iconography of Buddhist traditions as they move from Indian to China and other areas of Asia, there is mixing with and sometimes domination of local elements, but some continuities, even in light of major cultural changes.

Powerful icons can take on different historical attributes and still play an important role within a new cultural setting. Religious beliefs, such as the association of owls as messengers to the spirit world, may continue as a stream of thought that manifests itself in different iconography through time in cultures or populations that are vastly different. Owls as physical icons can move through time from spoons, to bowls, to weaving equipment, house posts and Sxwayxwey masks and change their role from powers of ritual to powers of vision or powers of wealth.

Stone bowls need to be viewed as changing phenomena on both a local and regional basis. Some stone figures may have been restricted to certain families who passed them on through their daughters as was done in historic times with the Swaywey performance privileges. This phenomenon is suggested in two reported cases (Keddie 1983). If this were the case, it might be that stylistic similarities are related to actual genetic connections between villages. Some stone bowls are strongly associated with the tobacco complex for a short period before the 4th century A.D. on the coast and possibly later in the interior of the province. The evidence suggests that some stone bowls dating to the period after about A.D. 800 may have been used as spinning bowls, even though this was not a known historic practice.

In the future we need to examine and undertake more thorough documentation of the large number and many types of stone figures within local areas. Only then will we have enough data to look at the broad picture of relations between centers within larger regions. Many of the stone figures in private and museum collections do have a site provenance and site-specific information that can be rooted out with a little detective work. More dating of these sites and the development of new fingerprinting techniques for source material should help cluster stone figure types in time and space and assist us to gain new knowledge on this subject.

Notes

1. Duff (1956, p.27) suggests that the Yale Creek bowl shows a bull snake, but the facial features are more like a Northwest rattlesnake.

2. Sample SFU 790, 1070±70, shell date with calibrated marine correction of 646 BP or A.D. 1310.

3. According to a letter sent by William Doe of the Government Telegraph Service in Victoria to Harlan Smith on March 11, 1922 the bowl was from Mayne Island and “It was turned up out of a sandy bank which the road men were cutting through for a new road, about two feet below the surface”. It is described as 4 inches in diameter and 3 inches high. On the Newcombe collection prints it is referred to as “ex Pender Island”.

4. Reginald C. Brooke assisted Harlan I. Smith, in 189798, at the Ebume and other sites around Port Hammond. Smith named one of the sites “Brooke’s Mound”. This is a different person than Brooks and the site should not be confused with the Brooks Mound discussed here.

5. see Duff ABC #5, p.90 and Plate 14D; Duff, Stone Images, p. 175, #48.

6. Photographs of artifacts taken by Ross Brooks about 1945 were passed to Angus McDonald (son of Mabel Orr) through the Brooks Estate and donated to the RBCM, July 5, 1980.