Originally published in Discovery 27(2).

1999.

The Loss and Return of Wild Bison.

by Grant Keddie

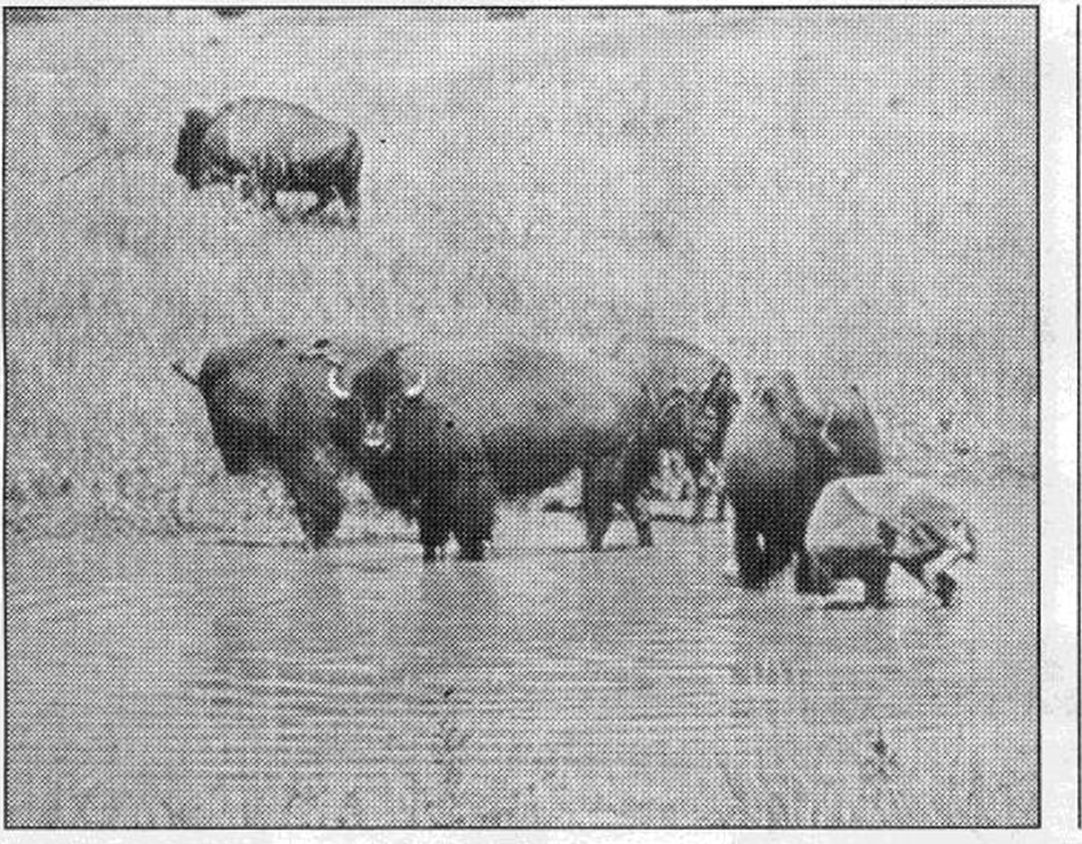

There I sat in the middle of the Bison herd. I was only three years old, but I remember it vividly. Along the Hay River near Great Slave Lake, my father had driven into the herd; we rolled down the windows and stared at these gentle beasts – they looked like a cross between teddy bears and cattle.

I maintained my interest by collecting “buffalo head” nickels and dragging home cattle skulls. But the chance to actually work with Bison bones did not come about until I began investigating finds and examining remains brought to the Royal BC Museum (RBCM).

Around 1500 AD, there were 30- to 40- million Bison in North America. They once extended from the Arctic to Mexico, although their range was already shrinking before the coming of Europeans. With the introduction of horses, guns and European trade, many aboriginal peoples focused more intensively on hunting Bison. By the 1840s, southern First Nations were killing two million a year and delivering 100,000 hides a year to traders. By 1850, non-aboriginal hunting doubled the hide trade and resulted in the final Bison slaughter of the 1870s. By 1889, there were only about 85 wild Bison in the US.

In Canada, Metis and aboriginal traders went out annually in huge hunting parties to supply food and hides. By 1874, Bison were only plentiful west of Saskatchewan and were gone from most of Western Canada by 1884. The last wild one on the Prairies was shot in 1889.

In British Columbia, records often refer to two subspecies of Bison: the Plains Bison or American Buffalo (Bison bison bison) and the Wood Bison (Bison bison athabascae). Some believe their difference in appearance resulted from adapting to different parts of their range – grasslands and boreal forest. Other researchers suggest that inadequate sampling has led to the unfounded conclusion of there being two subspecies. Bison have been adaptable, expanding and contracting their range as environments rapidly changed during and since the last Ice Age. They have not likely had a stable enough environment to develop as two, distinct subspecies.

In tracing the history of Bison in BC, evidence shows they were living in southern coastal British Columbia and Washington about 12,000 years ago. They were hunted in Washington for 4,000 years, disappeared and reappeared in parts of central and eastern Washington – mostly around 2,500 years ago when grasslands expanded. They again disappeared before 1500 – likely due to a combination of over-hunting and the Little Ice Age.

Historical reports from the early 1800s indicate Bison were common in the Peace River region, where archaeological remains show they were being hunted 10,000 years ago. In 1810, trader Daniel Harmon noted that Bison were found east of the Rocky Mountains “except for a few straggling ones” west of the Rockies. A Bison skull in the RBCM found in a bog near Atlin suggests they once extended even further west.

Alexander Anderson, who travelled as a fur trader through the province’s interior as early as 1830, wrote in 1867: “The Wood-Buffalo is found about the heads of Peace River, and between that vicinity and the Tete Jaune’s Cache. The neighbourhood of Cow-dung Lake [Yellow Head Pass] … exhibits vestiges of their former existence there until driven further off by the hunter.” In another context he notes: “The Wood-Buffalo is found along the Rocky Mountain ridge, near the head of Smoky River and elsewhere.”

Around Fort Dunvegan on the Peace River, the inhabitants feasted on Bison and supplied meat to other trading posts. But by 1849, when Eden Colvile, Governor of Rupert’s Land for the Hudson’s Bay Company visited, the situation had changed drastically. He wrote: “At Dunvegan they complain of a scarcity of provisions, owing to the large animals in the neighbourhood of the establishment having been too zoos became popular. Even cities sought closely hunted … during last winter, 40 Indians, men, women and children perished by starvation.”

In 1872, Charles Horetzky noted that the last bull was shot near Dunvegan two years earlier but “… There are still some stray bands away north of us, and they are even yet seen occasionally at Riviere Salee, quite close to Lake Athabasca.” By 1875, “Wood” Bison were nearly extinct south of the Peace River. About 550 were surviving near Great Slave Lake in the 1890s.

“Plains” Bison once extended up the eastern Rocky Mountain foothills to the south of the Yellowhead Pass area; Anderson noted that “Bison of the Plains” were not found west of the Rocky Mountains in “the Northern parts.” Along the southern border of BC they transplanted would have moved into the mountain passes and to Nahanni Butte on the lower Liard River of the NWT. Others have naturally crossed into BC from Alberta preserves by moving along the Hay River and other rivers crossed over alpine meadows. The Ktunaxa (Kootenay) First Nations went over the mountains twice a year on Bison hunts.

As Bison neared extinction, a number of enterprising individuals began to develop private herds. For example, Michel Pablo and Charles Allard of Montana acquired 10 Plains Bison in 1883 from a Pend d’Oreille First Nations named Samuel Walking Coyote. In 1893, they bought the remaining Bison of the “Buffalo” Jones herd of Omaha. When outdoor zoological displays in parks became the trend, the Canadian Government purchased the Pablo/Allard herd – and by 1911, 703 Plains Bison were settled in Alberta’s Buffalo National Park near Wainwright.

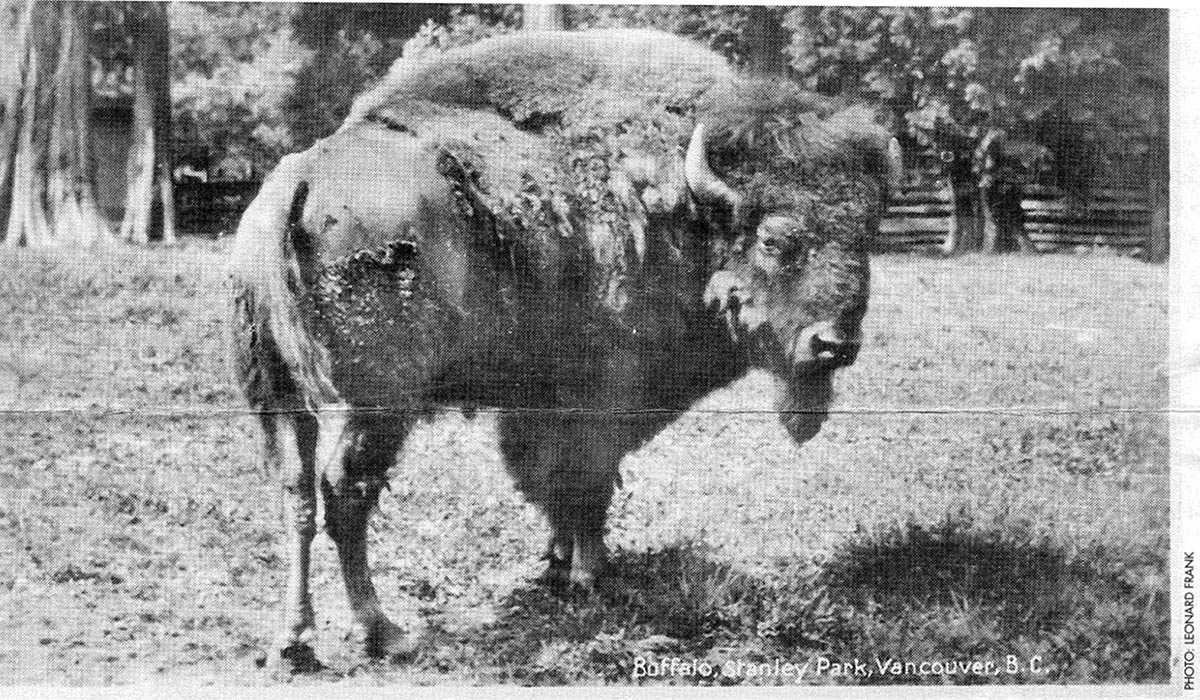

Transplanting Bison into parks and out animals – Victoria introduced Bison to Beacon Hill Park on May 20, 1928.

Wood Buffalo National Park was created in 1922 in northern Alberta and the NWT to protect the range of the last surviving 1,500 to 2,000 Wood Bison. In the late 1920s, 6,673 Plains Bison from Wainwright were added; the interbreeding was thought to result in the Wood Bison’s disappearance as a distinct subspecies. However, an isolated herd of “near pure Wood Bison” was found and 18 transferred to the Mackenzie Bison Sanctuary near Great Slave Lake.

In recent times, Wood Bison have moved naturally back into BC. Many originated from a herd that had been in the NE corner of the province. Also, Plains Bison were introduced in 1972 near Pink Mountain, northwest of Fort St. John, and now number over 1,000.

There are many chapters in the history of Bison, from their near extinction to their unusual rescue through private herds, city parks and government preserves to their natural return to wilderness. Today, somewhere between 1,000 and 2,000 Bison again reside in the wilds of BC.

As a follow up to this article I was one of the many authors of the following Science article. See for update on bison genetics:

2004. Rise and Fall of the Beringian Steppe Bison. Science, 306(26):1561-1565. Beth Shapiro, Alexei J. Drummond, Andrew Rambaut, et. al.