By Grant Keddie. 26-11-15.

Introduction

Chinese brass one cash coins were imported to British Columbia in the late 19th and early 20 century to be used as counter pieces in the gambling games of Fan Tan. The coin packages are now extremely rare and have never been described in print. In 1981, I purchased an unopened package of 280 Chinese brass one cash coins and a partially filled bag of coins from an opened package from Len Jenner of Courtenay.

Mr Jenner purchased the coins along with a large collection of Chinese cultural items from an elder Chinese man, known only as “Mr Lowe”. Mr Lowe had once lived on northern Vancouver Island, but the collection was purchased when he was living in Vancouver in the mid-1970s. Jenner documented information about the collection of Mr Lowe, who remembered distinctly that he purchased the coins in Victoria in 1911, when he was required by law to come to the city to get his photograph taken.

The Coin Package

The package is 11.5 by 6 cm. and has an outer covering of thin off-white paper. The front shows a red ink stamp mark of a man waving a flag (possibly representing the revolution of 1911). There are three Chinese characters on the Flag which name the store selling the coins. The literal translation in Cantonese is Cheung Sung Mai or Lucky, Live, Beautiful. There are four characters under the man waving the flag which could be interpreted as meaning: “This is a package of good coins”. Along the side of the package is a row of 5 characters which translates approximately as: “There are 280 pieces in one package or one whole set” (Translations by Siu Leong and Bitje Chan of Victoria).

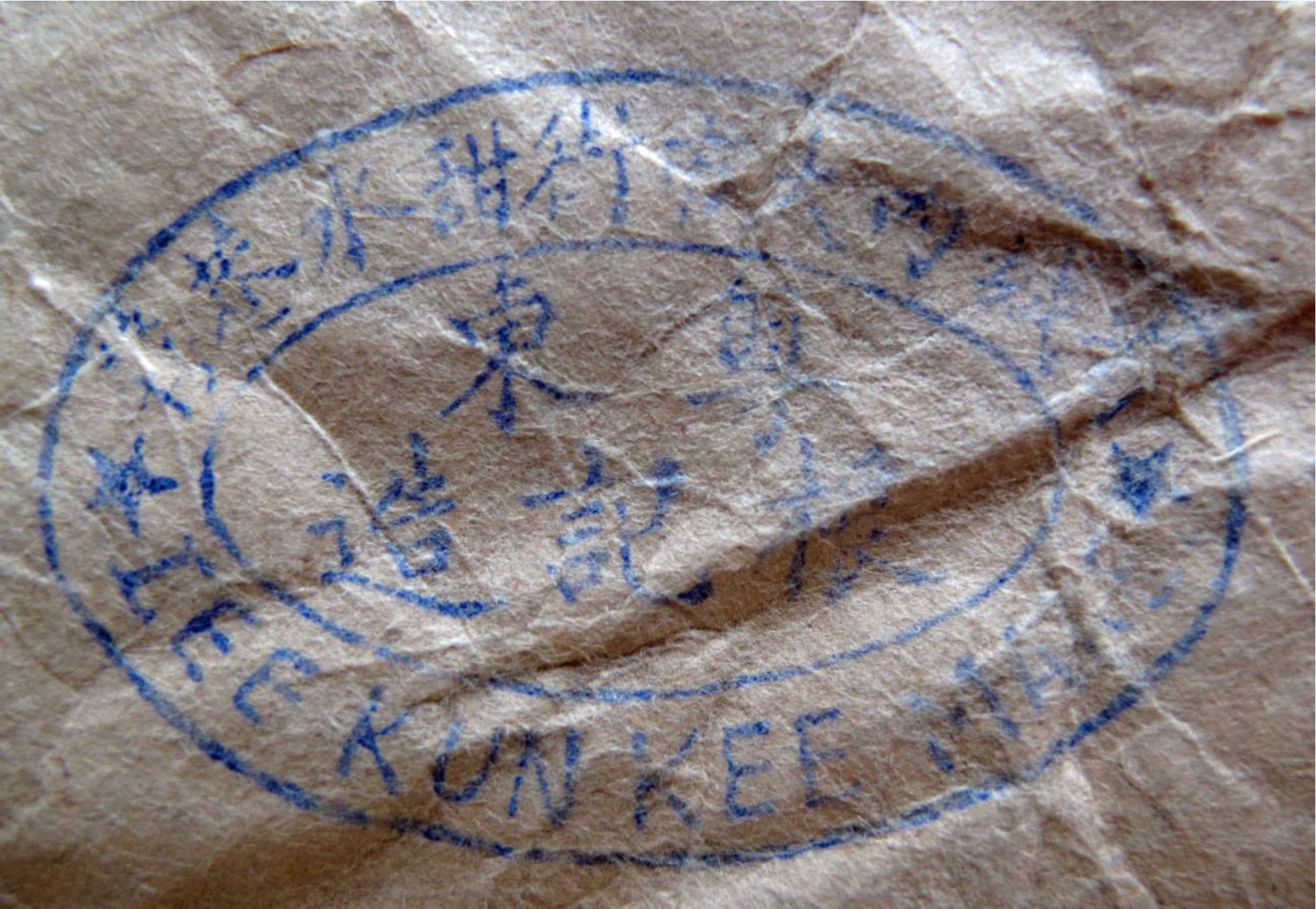

Opening of the package revealed a second paper wrapping tied with a small piece of red string. Inside this was a third paper wrapping with a blue oval ink stamp. Inside the edge of the top of the oval are ten characters giving the address of the store: “49 Sweet Water Street”. At the inside bottom of the oval are the English words “LEE KUN KEE MAKE”. An inner oval has five large characters: “Canton” and below this the person who owns the store “LEE” – followed by the name of the store “KUN KEE”.

Inside this third wrapper is a Black cloth bag with a white pull string containing four bundles of coins. Each bundle consists of two rows of 35 coins tied together with string. All but three of the 280 coins are from the Ch’ien Lung period (1736-1796). Four different mint marks are present – Yuan mint (195 coins); Ch’uan mint (77 coins); Chih mint (4 coins) and the Chin mint (one coin). Three coins are from the Chia Ching period (1796-1820) and all from the Yuan mint.

The coins are uncirculated and do not appear to be reproductions. Culin, in his observation of Fan Tan games in the United States in 1891, notes that some of the stings of cash appear to be uncirculated “and are probably reproductions made expressly for gambling purposes (Culin 1891:5-6)”. Reproductions were made for coins to be attached as decoration to commercial items but these are either different in some way from the official minted coins or are specimens that have lost much of their detailing. It is likely that many of the uncirculated coins where brought out of storage and repackaged for the American market. Culin observed in 1891 that only perfect pieces were used with a preference for those of the same mintage. He noted that they are cleaned with vinegar and afterward polished by being shaken with damp sawdust in a cotton bag.

Culin observed that coins used in Fan Tan were the same as those current in China and coins from the Kang Hsi period (1661 to 1722) and Chien Lung period (1736 to 1796) formed a large part of the coins in circulation. He noted that “all the emperors of the Manchu dynasty, except the present ruler [Kwong-shui 1875-1908], may be found upon these strings of cash, and a collection embracing the issues of many of the provincial mints can be formed from them (Culin 1891:5)”.

Ed Lee and the Cash Coins from the Nanaimo Museum

In the Nanaimo Museum I observed strings of coins that included both Annamese zinc coins [catalogue 978.215] and Chinese copper coins [catalogue 978.214]. The latter, numbering about 126 were mostly from Yuan or Ch’uan mints. They were donated Dec. 12, 1978 by Ed Lee of Chase River.

I contacted Mr Lee, who told me he found them in an abandoned building in Nanaimo’s China town after it burnt down in 1960. He remembered the coins used in Fan Tan being contained in a cotton sack and wrapped in rice paper. He remembers the Annamese coins were valued at 1/10 of a cent. In Annam (southern Vietnam), 10 zinc Dong were equal to one copper Dong. Ed Lee said that the Chien Lung coins were valued at 1/4 of a cent because it was believed that they had some gold in them. This idea fits with the fact that the Japanese took many Chien Lung coins out of circulation to melt them down for gold. The coins were used mostly before 1911, but were common in the 1920’s and 1930’s. They were increasingly less common to the 1940’s and replaced by buttons after 1940. Mr Lee said Fan Tan players would wash the coins every half hour because they get covered in sweat.

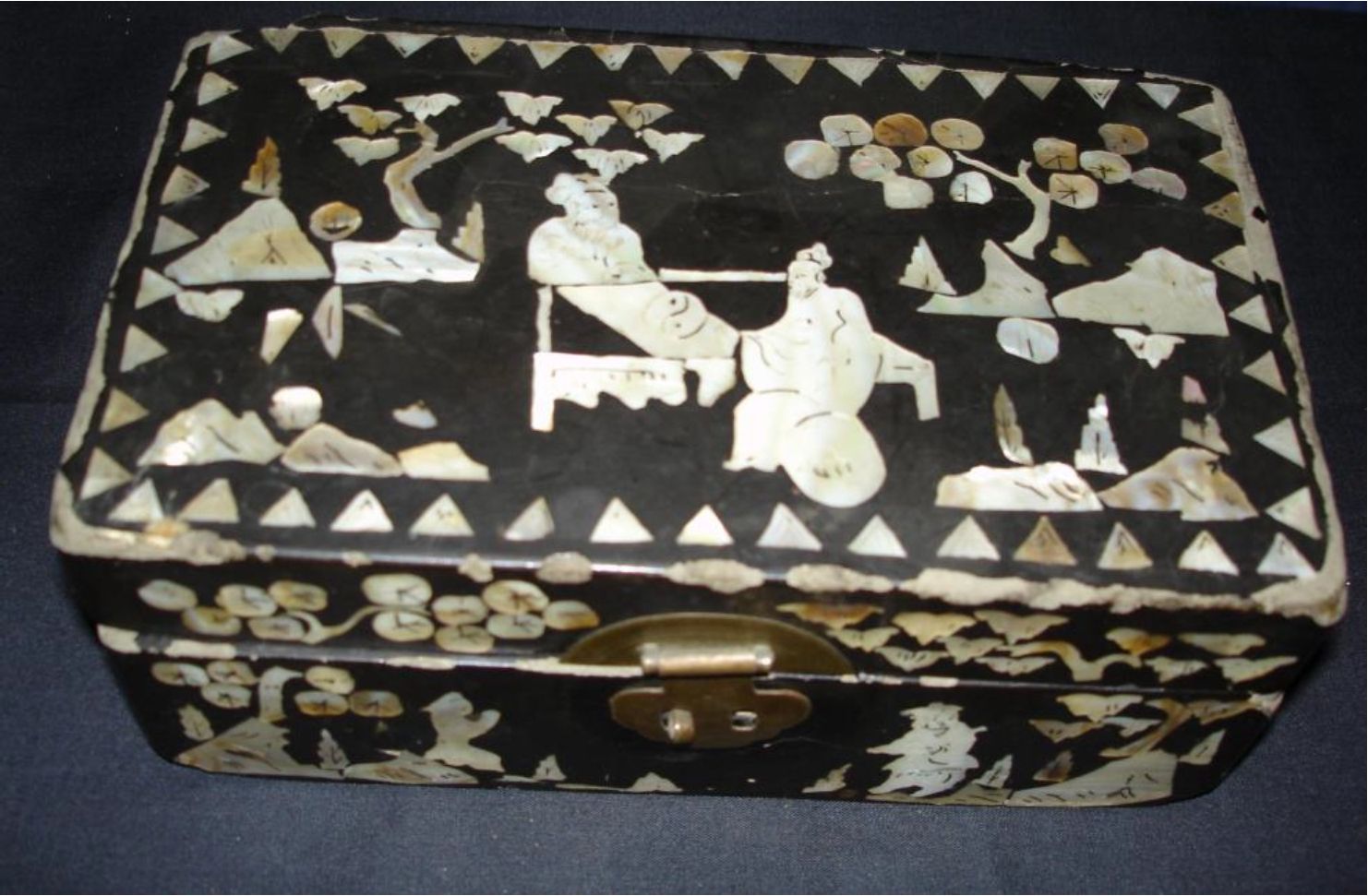

In the early 1970s, I obtained several tin boxes that were previously used in gambling activities in Fan Tan Alley from an elderly Chinese Canadian who had played there himself. Figure 4, shows one these with an associated brass lid. The lid was used to capture a group of buttons while players bet on whether the hidden number of buttons was odd or even. The Chinese characters on the box indicate the fan tan table number where this tin box was used. While in the building on the west side of Fan Tan Alley just north of a side alley, I observed six distinct, evenly spaced, black smoke rings on the ceiling above where the gambling tables once stood.

Trade and Value

In 1807, a Chinese tale was worth 1 dollar and 48 cents American. Since there were 1000 cash in a tale, an American cent was equivalent to 6.75 Chinese cash pieces (Walsh 1807). Later in the 19th century cash pieces often passed at eighty to the dollar because they were at a premium, but after 1905 a flooded coin market reduced their value to as much as 600 to the dollar in some provinces (Coole 1965:3). Due to the low value of these Chinese cash pieces in the 1790 to 1830 period, and First Nations interest in copper ornament these coins were brought from China in large numbers to trade on the Northwest Coast of America (Keddie 1990).

References

Coole, Arthur Bradden. 1965. Coins in China’s History (4th Ed.). Inter-Collegiate Press, Mission, Kansas.

Culin, Stewart. 1893. Chinese Games with Dice and Dominos. Annual Report of the U.S. National Museum, Smithsonian Institution, for the year ending June 30, 1893. Pages 491-537.

Keddie, Grant. 1990. The Question of Asiatic Objects on the North Pacific Coast of America: Historic or Prehistoric? Contributions to Human History. Royal British Columbia Museum, Victoria.

Walsh, Michael. 1807. A New System of Mercantile Arithmetic; Adapted to the Commerce of the United States, in its Domestic and Foreign Relations; with Forms of Accounts, and Other Writings Usually Occurring in Trade, The Press of Zadok Cramer, Pittsburgh.