Originally published in The Midden, 24(3).

2011.

By Grant Keddie

David Scott’s Discovery and the Never Ending Story

The topic of trans-Pacific contact is a controversial one. It is often said of academics that they ignore evidence that does not fit the accepted status quo. The story of this case is an interesting scenario of how the discovery of an artifact is dealt with when it does not fit our understanding of local history. This story transcends a period of four Museum Curators and now 62 years later is still unresolved. Are we dealing with evidence of ancient long distance trans-Pacific voyaging, long distant trade between the continents of the New World, or an example of unusual refuse from the early 20th century?

Emma Scott and Arthur Pickford

On October 4, 1949, Emma Scott of Penticton, sent a letter to the Director of the Provincial Museum, Clifford Carl. Her letter was prompted by a newspaper story about Museum personnel visiting a shell midden site at Lyall harbour:

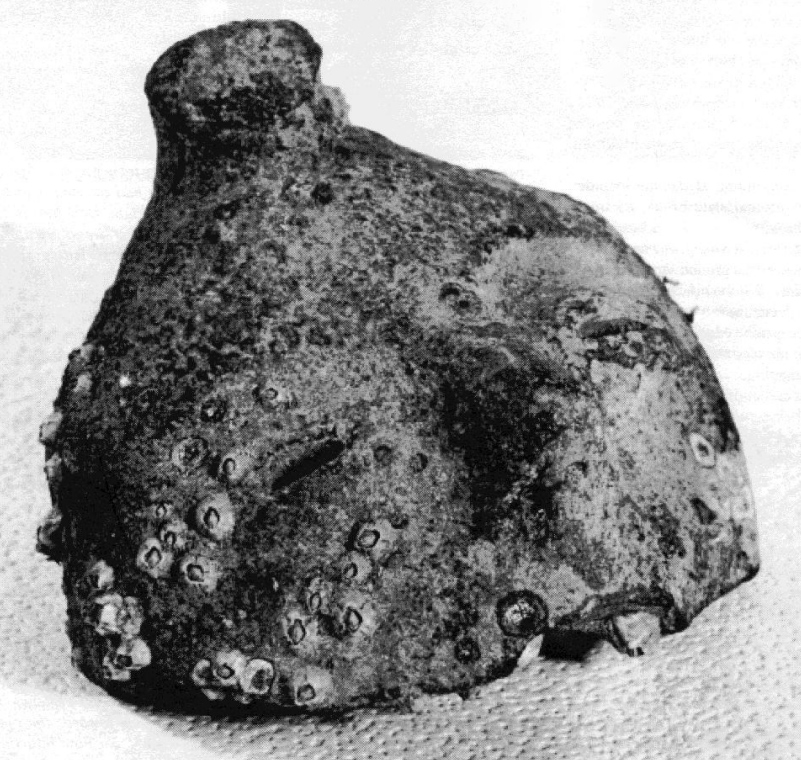

“When we were at Lyall Harbour on Saturna Island this summer our young son [David] picked up a small mask near the large midden. The tide was out and he picked it up a short distance below the water line.”

The Lyall Harbour site, DeRt-9, has never been excavated by archaeologists. In my visits to the site I have observed cultural debris up to 2.5 meters in depth. At least a meter of shoreline midden has eroded away in the last 30 years.

Artifacts surface collected from site over the last 80 years allow us to only guess that it may have been occupied intermittently between about 2000 and 800 years ago. There is no record of the site being occupied by First Nations in Historic times. A small blue, wire-wound Chinese made trade bead dating to the 19th century was found at the site, but is not necessarily indicative of aboriginal occupation. I undertook a systematic collection of artifacts from the beach on August 2. 1982, and April 11,1995, and the only pottery fragments 1 found were of recent European or Asian manufacture.

Artifacts found at the site include: 127 small ground slate beads; 14 small shell beads with one larger flat bead and a section of a toredo worm caste bead; three small stone celts; a ground serpentine projectile point; 32 stone bifaces or projectile points of dacite, basalt and chert; a chert tool with a ground edge, 13 stone flakes; a sandstone abrader and a green stone with heavy scrapping.

The ceramic head was sent to Clifford Carl along with Emma Scott’s letter of October 6*. Carl, a biologist by training, wrote Emma Scott:

“I do not believe the specimen you have sent for examination is of Indian origin. It appears to be a form of pottery and so far as known our natives had no knowledge of pottery or clay work. However, as a check we will hold the specimen for a few days until we can have someone else look it over. ”

Carl passed the letter to Arthur Pickford, whom he referred to as a “consulting anthropologist.” Pickford had left the Museum on June 30, 1948, after being employed as an “assistant in Anthropology” since 1944. As a horticulturalist, he worked for the Provincial Forestry Branch as a land surveyor and as creator of B.C. ’s reforestation program. He had his own artifact collection and considered himself an amateur archaeologist. He had worked with First Nations and developed a keen interest in ethnobotany and archaeology, later publishing material on both subjects. He came to the Museum after he retired from the Forestry Branch.

On October 8, 1949, Pickford wrote to Emma Scott: “We are very intrigued by this specimen … we would like to have more details as to the condition under which it was found. ” He then asked specific provenience questions. Mrs. Scott replied:

“1. The exact location of the find was at the south East end of Lyall Harbour. This is a very sheltered spot where canoes could be drawn up. 2. There are indications of Indian life in that locality in the form of a very large deposit of shells in which a number of Indian relics have been found. 3. Yes the mask was found on the beach about twenty feet beyond the shoreline and about thirty or forty feet to the right of the shell deposit referred to. 4. We do not know if any other pieces ofpottery have been found— but Mr. And Mrs. Jim Money of Saturna Island told us they had found several interesting relics in the same midden. ”

Mrs. Scott gave the Museum permission to “keep it for a month or two” and mentioned that it was their ten year old son David who found it.

On October 13, Betty C. Newton (assistant preparatory) sent a letter to Emma Scott explaining that the head was being photographed and would be returned “in about ten day’s time.” On November 16, Newton again wrote to Scott explaining that the artifact would be delayed in its return because Pickford had just returned the ceramic head the day before and was “anxious to photograph it again with a special camera he hopes to have loaned to him.”

On November 18, Emma Scott wrote Newton: “Please tell Mr. Pickford he is welcome to keep the head longer. If he should like to take the barnacles off he is at liberty to do so. It might improve the photograph.”

April 30, 1950, Pickford wrote to Emma Scott. After giving an excuse for not returning the head, he states:

“We have not yet been able to solve the enigma of a work of art in pottery of a primitive nature being found associated with the kitchen midden of non-pottery making aborigines of this country.”

He asks her permission to take it to the May 1950, Northwest Anthropological Conference in Seattle “and there submit it to the opinions and experience of the Anthropological experts.”

On June 23, 1950, Pickford wrote Emma Scott saying he wanted to hold ( it “just a little longer” to show it to Dr. Douglas Leitchman of the National Museum who had arrived from Ottawa. Pickford stated:

“At the Anthropological conference …I brought it to the attention of Drs. Ralph Roys, Gordon F. Elkholm of the American Museum of Natural History, and others. All of these were tremendously interested, but none had an idea to suggest as to its origin. Dr. Erna Gunther, of the University of Washington (As I thought, wishing she had found it herself) looked at it with a semblance of disinterest and suggested that it could be none other than the discard of some recent visitor to Central America who had been temporarily interested in the original Rain-God figurine of which (she suggests) that was a part. I made a tentative promise to the more responsible among the anthropologists that I would pay a visit to Saturna and view the site with a view to reporting as to conditions and further evidence. However, being on a very poor pension, funds do not permit of my carrying this project into effect for the present.”

On June 27, 1950. Pickford wrote Emma Scott reporting that Dr. Leitchman: “lacking further evidence is rather inclined to lean towards the opinion of Dr. Gunther. I am now returning your treasured specimen to you by registered mail as you request.”

Emma Scott and Wilson Duff

Wilson Duff became the Curator of Anthropology at the Museum in June of 1950, but it was not until two years later that he saw photographs of the ceramic figure. At this lime the museum did not have most of the previous correspondence—these likely remained in the private papers of Pickford. On January 21. 1953, Duff wrote to Emma Scott asking to borrow the “image of a human head, made of pottery or dried clay ” for his “exhaustive study of the ancient stone and other sculpture of this area … Your specimen, if our information is correct, is of great importance as it introduces a new type of sculpture—moulding. ” Duff’s study was published in 1956 with no mention of the Saturna Island ceramic head.

On January 23, Emma Scott wrote back to say she is sending the figure to the Museum. She reiterated information previously given to Pickford. She suggested that Duff write Jim Money of Saturna Island regarding artifacts found at the site. On January 28, Duff writes back:

“Many thanks for the loan of the pottery head. It is a strange thing, and definitely does not belong to this area. The closest things I know of similar to it are the pottery figurines of pre-Aztec Mexico. With your permission I will keep it a while longer to be photographed and studied further.”

On February 11,1953, Wilson Duff writes to Jim E. Money:

“…The object seems to me to be of Mexican origin possible part of a mould-made pottery figurine of pre-Aztec times (before about HOOA.D.). The question is, of course, how did it get to Saturna Island. It is the sort of thing that a traveler in Mexico might easily acquire as a souvenir. Do you know if any of the residents of your area or visitors have ever been to Mexico or have collections of Mexican souvenirs? In the same connection I would he interested in anything you can tell me about Indian middens or other remains on the island, and the types of relics that have been discovered there.”

On February 15, Money writes Duff:

“David, Mrs. Scotts’ son told me he found the head some 400ft out at Lyall beach when the tide was extremely low. Most of Lyall beach is very muddy at low tide but there is a reef of hard shale which runs out a long way and would hold up anything from sinking into the mud. …We have enquired around Saturna and can find no one who has any collection of Mexican pottery or anyone that has ever been south of the American border.”

On March 10, 1953. Duff sent a letter to Emma Scott:

“I am returning to you the broken pottery head… I think it is part of a Mexican (pre-Aztec) mould made pottery figurine. 1 have sent photographs for positive identification to Washington, D.C., …As soon as I find out more, I’ll let you know.”

On March 24, 1953, Gordon Eckholm of the American Museum of Natural History wrote to Duff:

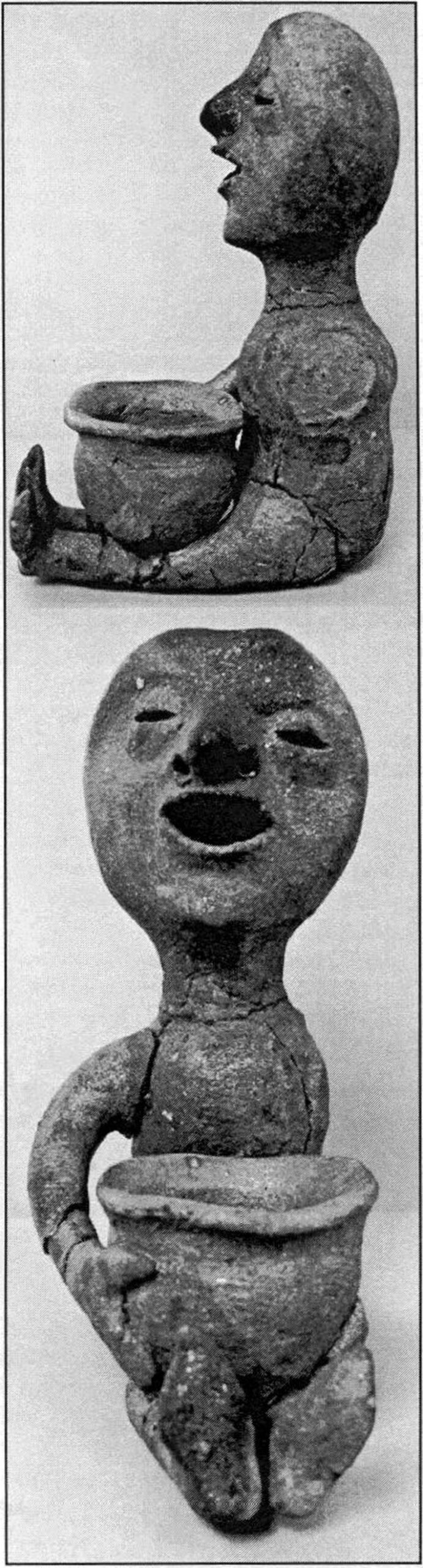

“Dr. Roberts of the Bureau of American Ethnology has forwarded to me your correspondence and the pictures of the figure head …with the idea that I might comment on the figure’s possible Mexican affiliation. … The figure does not suggest any Mexican style of which I know. It certainly does not resemble anything in the well known figurine complexes of Central Mexico, either pre-Aztec or Aztec. There are many less well known local styles in other portions of Middle America and occasional variants which do not form recognizable styles, but on the whole I am fairly well convinced that it could not be Mexican. Hollow figures are not so common and 1 particularly haven’t seen anything with the peculiarity of a central topknot of the kind possessed by your figurine.

But I think 1 have another solution for you. The figurine bears considerable resemblance to the so- called Haniwa figurines of Japan, suggested to me in thefirst place by Mr. Fairservis of our department. 1 haven’t gone very far in searching out illustrations of these.”

Eckholm points out figures in N.G. Munro’s Prehistoric Japan (1911) and William Gowland’s The Dolmens and Burial Mounds of Japan (1897), as well as H. Motoyama’s Relics of Japanese Stone Age. He notes that:

“Not all of the Haniwa figurines are closely similar to your piece, but all of them are hollow with slit eyes and mouth, some have the top knot and some have a very similar outline. And note particularly Fig.

395 in Munro which shows red face painting on the mouths of a number o f them which may be the red color on yours. I gather that the Haniwa figurines date to about 400 A.D. … This looks to me like a very interesting find, and I think you should follow it up in detail. Found near a midden site …it probably comes from the refuse of that site. It might be that some digging would be worth while and you should, with this possible lead, get some experts in the Japanese field to look at it. You will be well aware of the potential importance of tying up one of your sites with a definite period of the Japanese sequence.”

On March 31, 1953, Duff explained to Emma Scott the contents of Eckholm’s letter:

“He identifies it as a Japanese Haniwa figurine which may date back to about 400 A.D. This of course raises a lot of questions, which I intend to follow up. I’ll let you know of any further developments.”

The same day Duff wrote to Dr. Wayne Suttles, then at the Museum of Anthropology, University of British Columbia and later a professor of Anthropology at Portland State University. Suttles was an expert on Salish languages but worked during the war years breaking Japanese codes and spent some time in Japan after the war:

“I have just received a letter from Gordon Ekholm in which he identifies the object pictured in the enclosed photographs as a Japanese Haniwa figure. Isn’t that just what you said? I would be obliged if you would look at your books and see if you can pin it down exactly.”

My discussions with Wayne Suttles in the 1990s indicated that he did not take this conversation any further, in terms of identification of the figure.

On April 1, 1953, Frank H. H. Roberts, Jr., of the Bureau of American Ethnology, writes to Duff:

“After receiving a copy of Dr. Gordon F. Ekholm s report …we referred the previous correspondence and photographs to Dr. A. G. Wen- ley, Director of the Freer Gallery of Art. His comment is as follows:

‘I cannot identify this piece definitely, and of course it is of very small size. However, it is not unlike pieces found in some quantity in the northern part of the main island of Japan, in the general area of Qu. It certainly seems to be a curious piece to find near Vancouver ’

Dr. Wenley is an expert on Japanese art, but according to him, ‘not on archaeological artifacts.’

It will be interesting to hear what Dr.[Phillip] Drucker has to say about the specimen.”

David Scott and Don Abbott

On August 8,1960, Don Abbott joined the Museum as an assistant in Anthropology. When Duff left in 1965, Abbott became the Curator of Anthropology and, in 1967, the first Curator of Archaeology. That year, on December 12, David Scott wrote to the Museum requesting the return of the pottery head and “any positive identification that has been made on this head.”

Don Abbott wrote a reply letter of inquiry to David Scott on December 19. At this time Abbott did not have copies of earlier letters. Although 1 later located a Temporary Specimen Receipt dated Nov. 27, 1962, and made out to Mrs. J. Scott, it appears that the artifact had been mistakenly accessioned into the Museum collection on Oct. 18, 1963 (old# 11841). Abbott asked David if he would consider donating it: “since the possible cultural significance of such a specimen makes it much more appropriate in the Museum Collection than in private hands.” David wrote back on December 23, asking for its return.

On January 10, 1968, Abbott again wrote David Scott:

“Please excuse my delay in answering your letter of December 23rd. Prior to returning your pottery head from Saturna Island 1 decided to try one last time to get an identification and I showed it to a new member of our staff, Mr. Philip Ward, who is an expert on oriental material culture. Somewhat to my surprise he was quite excited about it and identified it tentatively as early Japanese, probably from the Yayoi Period which dates approximately from 200 B.C. to 200A.D. Because of this apparent importance, of which I had previously been unaware, Mr. Ward wished to keep it for a few days to make a full photographic record and also to make a cast. He has almost finished doing this and you can be sure I shall send it to you as soon as possible within a few days.

Of course the real significance of this find is still obscure as we can only guess how it got on the beach where your mother found it. It may just have been dropped there in recent years by a collector or somebody else who happened to have it in his possession. The most exciting possibility, of course, would be if it had been eroded out of an old midden at that spot and was therefore associated with an ancient archaeological site. I would certainly not be very inclined to raise very high hopes for that possibility but I do think it is important now to find out precisely where this was found since we do not seem to have that record. If you could let us know this we would like to check the location to see if there is, in fact, a site there and. if so, whether it would possibly repay professional excavation.”

From my own discussions with chief conservator Philip Ward he did not consider himself an expert on the subject, although he had trained under experts and had an interest in Asian ceramics.

On January 10, 1968, Ward wrote to two individuals. The first was to R. Soame Jenyns (Department of Oriental Antiquities, British Museum):

“I was most interested by your remarks on the possibility of transpacific contacts and it is a coincidence that your letter should arrive just as I was about to write to you on this very subject. I enclose some photographs of an object which has come to me for identification. … With the Valdivia site in Ecuador in mind, I wonder if it could possibly be pre-Buddhist Japanese—perhaps Yayoi? I realize that you will probably think me crazy, but I am always looking out for something of the kind. The ocean currents are entirely favourable to voyages from Japan to this coast. Japanese glass fishing net floats are constantly washed up on the west coast of the island and there are numerous records of disabled junks being wrecked on the bar of the Columbia River in Oregon during the last century. 1 really would be most interested to have your opinion of this fragment.”

Ward was overstating the known extent of Japanese shipwrecks here. In my own studies I have shown that Japanese glass floats were only made starting in 1911 and there is only one verified 19′h century Japanese shipwreck off the coast of Washington Stale and none off the coast of British Columbia (Keddie 1994).

The second letter was to Professor W. Watson (School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London). This letter is similar to that written to Dr. Jenyns. Pictures were included and Ward commented:

“It is certainly not of local origin and our anthropologists feel that it cannot be American at all. …I wonder if it could be Japanese—say Yayoi? Of course, my judgment may be unreliable for reasons other than my ignorance. With the Valdivia site in mind, 1 have been looking for something of this sort ever since I got here.

Many here feel, as I do, that there have been numerous trans-Pacific contacts, presumably from Japan, in prehistoric times. …like everyone else I know here who is familiar with oriental material, I feel sure that there is some elusive cultural connection.”

On February 7, 1968, Watson replies:

“The less agreeable part of your letter is that it requires me to identify a clay object which I agree so resembles some of the haniwa heads that it may be of Japanese origin. The head with the tuft on top is one of the fairly standard types and in this piece the slit eyes look right.

Neverless as you probably anticipate I hesitate to say that this is haniwa and if it proves to he one please don’t conclude that the Chou-Mao-shu [Yayoi] people invaded British Columbia. I suggest you send the photographs or even the piece to the National Museum Tokyo …I have a feeling that the clay, if one can judge by the photographs, is thicker and coarser than the clay of haniwa that I have seen.”

On January 24, 1968, David Scott writes to Abbott: “I gather that you do not have copies of the correspondence regarding the pottery head. I am therefore enclosing copies of the letters. I have as well as the answer to Mr. Pickford’s of Oct 8, 1949.” David requested the return of the ceramic head “within the near future”—it was returned on January 31.

On February 2, 1968, a newspaper article appeared in the Victoria Colonist by Humphrey Davy with the Title: “Orientals First to Reach Coast? Tiny Piece of Pottery’ Raises Questions. ” It summarized second hand information obtained at the Museum and added a few other specula- live statements:

“The specimen is expected to spur a widespread search this summer for similar artifacts and could lead to one of the most important archaeological finds in the history of the province.”

On February 6, 1968, Abbott writes to Scott and comments on the newspaper article and states that the copies of correspondence:

“Are of interest to us and obviously of considerable embarrassment as well. There are clearly some deficiencies in our filing system because in a previous search we had not found any of this correspondence. It is certainly a shame that three successive curators have had to go through the same cycle of interest and investigation.”

Abbott enclosed a copy of Jenyns replay to Ward. Abbott states:

“Mr. Ward, who knows Jenyns quite well, interprets his apparently highly tentative identification of it as Japanese to be, in fact, quite strong confirmation since Jenys is, apparently, particularly cautious in these matters. …We do hope to consult with contacts on Saturna Island regarding this site and, if it sounds as if it might be profitable, to have a look at it ourselves.

You might have seen or heard of a recent write up on this subject in the Victoria Times. I can only tell you about this not only is it totally garbled and inaccurate but it was written and printed without my authorization or even knowledge since I was out of town at the time.”

On February 20. 1968, Abbott writes to the National Museum in Tokyo, Japan with attached photographs:

“As a result of enquiries we have made up to now, the consensus seems to he that it is most likely a Haniwa figurine of the Yayoi Period in Japan. Of course, while the possibility that it actually came out of the adjacent prehistoric site must be considered very remote, it is not beyond al! reason that this specimen could be evidence of an ancient culture link between Japan and British Columbia. I have not inspected the site in person though I mean to do so as soon as possible … Whether or not we do decide to follow this up with greater vigour will depend to a large degree upon your reaction to the specimen. I understand that artifacts of this type are rather rare and unlikely to be found in private collections outside of Japan so that the obvious alternative that the piece was lost in very recent years by some collector sounds unlikely. Would you agree with this? Is it conceivable that such an artifact could have been transported here by ocean currents?”

On February 21, 1968, Abbott sent a letter to David Scott enclosing Ward’s letter and his reply from Watson. On April 23, Abbott received a letter from Takeshi Ogiwara (International Relations) of Tokyo National Museum: “I showed their (sic) photographs to a specialist in our Archaeological Department, and I was told that they are neither haniwa figures nor dogu (clay figures). I think they have nothing to do with Haniwa figures. ”

Grant Keddie

When I came to the Museum in 1972, as a curator in Archaeology, I was intrigued at seeing the cast (DeRt-9:C233) of this artifact. Over the years I looked for similar artifacts to the Saturna Island head. I visited and searched the site location several times. In the literature I found a few resemblances in upper facial features such as those in El Molle culture of Chile (Charlin 1969:fig. 1), but the larger mouth and top knot did not fit.

A ceramic figure from the final Jomon period, dated to 1000 to 300 B.C. from the Ohnakayama site at Nanae on Hokkaido Island resembles the Saturna head in the eyes and nose, but like the El Molle figures has a mouth that is too small. Small ceramic figurines served as house deities or charms to protect women from disease and the dangers of childbirth and were used for thousands of years in northeast Asia (see Kikuchi 1999:50. fig. 4.6; Zak 1969:12; slide 23).

I have ruled out any connection to Yayoi culture (400 bc – 250 ad). On at least five occasions I had the opportunity to ask individuals or groups of Japanese visiting scholars their opinion on the Saturna Island head. All stated that they did not think it was Japanese—especially the nose. Two individuals did suggest that it was generally similar to some of the smaller figures in the northern regions of Japan.

Tesuque Rain God?

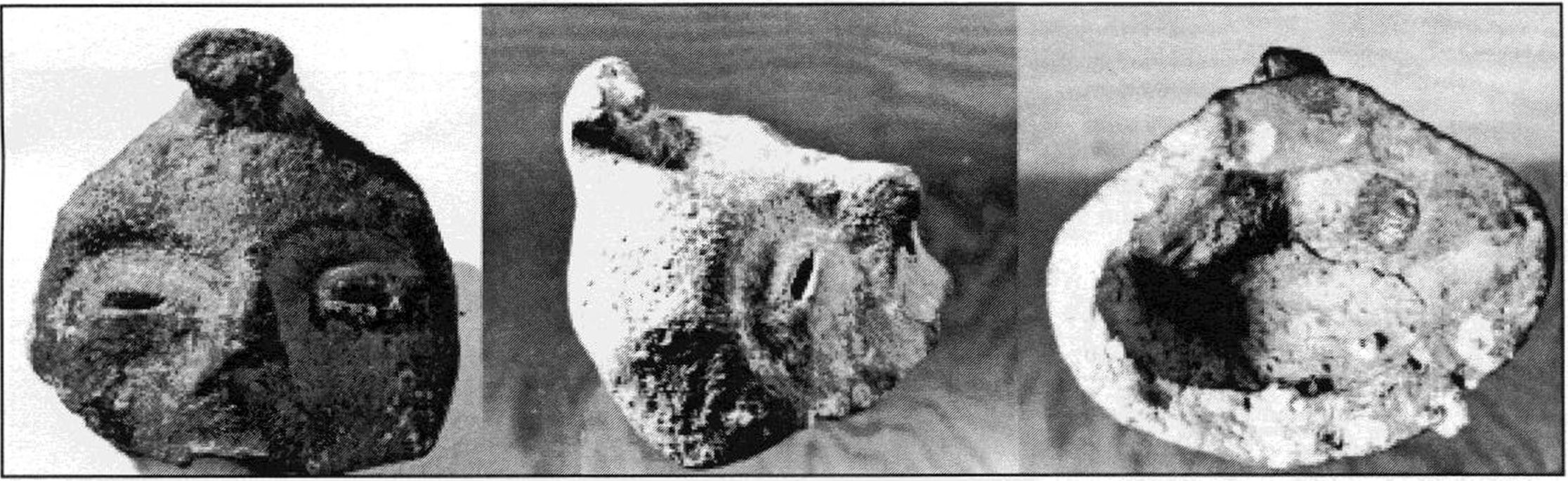

One image I found resembling the Saturna head was a figure from Tesuque, New Mexico. Knowing that Dr. Roy Carlson of Simon Fraser University had lots of experience in the Southwest, I took photographs of the head, and without any prompting, asked for his opinion on the origin of the figure. He said: “Well, it looks like a Tesuque Rain God from the American Southwest to me. ” This prompted me to focus on Tesuque Rain Gods. The more I researched, the more this seemed to be the answer. The ceramic figures that most closely resembled the head were those made around the 1890s for the tourist industry. Some had top knots, but not identical to the Saturna Island artifact. Many of these figures were made for sale at Tesuque, especially beginning in the late 1890s when they were sold by the Gunther Candy Company of Chicago. They were put as prizes in special boxes of Candy (Cole 1955; Edelman and Ortiz 1979).

In the RBCM collection we have, what 1 would consider, a 20th century Tesuque figurine that was part of a Gulf Islands collection once owned by Herb Spalding. A note in the collection indicated that Spalding had acquired the figure from Larry Moore of Shaw Island in Washington State. It is not known where Moore acquired it. The mostly complete Shaw Island figure is very similar to other Tesuque Rain Gods. A comparison with the Saturna Island specimen shows some differences such as the sharper profile of the nose and the nostril holes being slats closer to the middle compared to those more spread out in the wider nose of the Tesuque figures.

Dating of the artifact

I phoned David Scott in the 1980s, when he was living in Vancouver. He still had the original ceramic head at that time. I discussed the possibility of dating the object. I tried to find someone to do thermoluminescence dating of the artifact but it was too expensive al the time. In order to confirm or rule out the connection with Tesuque Rain Gods, there needs to be an analysis undertaken on the original ceramic head using XRF (X-ray florescence). This would also require an analysis of a number of Tesuque Rain God figures in American Museums for comparative purposes. My inquiries revealed that XRF studies had not been undertaken on historic Tesuque figures.

David Scott has moved from his previous address; I am now trying to relocate him and see if I can undertake the necessary analysis on the figurine. But, just in case this story drags on and someone else needs to follow-up, I thought I should publish my results on the still mysterious pottery mask of Saturna Island.

References

Charlin. Jorge Iribarren. 1969. Vasos – figures, en la Cultura El Molle. Publicationes del Museo Arquaologica de Lu Serena — Boletin No. 13:58-62. Chile.

Cole. Fat-Cooper. 1955. Tesuque Rain Gods. The Living Museum 16(9):550-551.

Duff. Wilson. 1956. Prehistoric Stone Sculpture of the Fraser River and Gulf of George. In: Anthropology in British Columbia. No. 5. British Columbia Provincial Museum. Department of Education, Victoria, pp. 15-151.

Edelman. Sandra A. and Alfonso Ortiz. 1979. Tesuque Pueblo. Pp. 330-335. Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 9, Southwest, edited by Alfonso Ortiz. Smithsonian Institution. Washington.

Keddie. Grant. 1994. Human History: Japanese Shipwrecks in British Columbia—Myths and facts. The Question of Cultural Exchanges with the Northwest Coast of America. Electronic document, accessed 13 September 2011. http:// www.royalbcmuseum.bc.ca/Contcnt_ Files/Files/JapaneseShipwrecks.pdf.

Kikuchi, Toshiniko. 1999. Ainu Ties with Ancient Cultures of Northeast Asia, pp. 47-51. In Ainu. Spirit of a Northern People by William W. Fitzhugh and Chi- sato O. DubreuiL Arctic Studies Center. National Museum of Natural History. Smithsonian Institution in association with University of Washington Press.

Zak. Ellen. 1979. Image and Life. 50.000 years of Japanese Prehistory (Teaching Kit) Center for Japanese Studies. The University of Michigan. Ann Arbor.