By Grant Keddie. June 3, 2023.

Introduction

It has occasionally been assumed that photographs of small white dogs with Indigenous people or on Indigenous reserves in late 19th and early 20th century are “wool dogs”. This is not likely the case as these dogs had become extinct as a physical type before this time period. The dog images referred to above do not fit specific characteristics of the wool dogs and are most likely one of several varieties of small white dogs introduced from Europe as far back as the 1850s. See Appendix 1 for the images and commentary on dogs suggested as wool dogs.

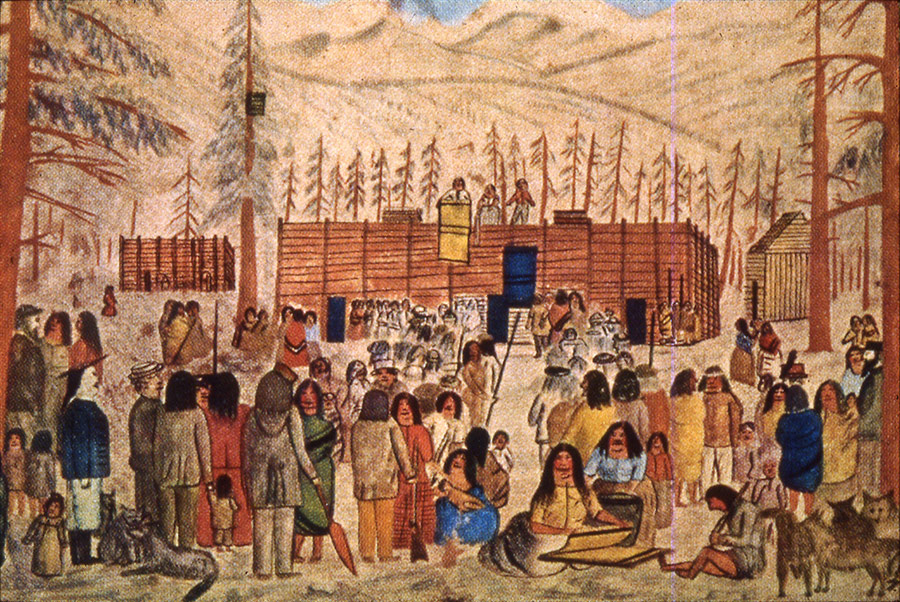

In 19th century British Columbia non-Indigenous dogs were brought here by explorers, gold miners, surveyors, ranchers and hunters. These generally were medium size to larger dogs that rapidly interbred with and replaced Indigenous dogs. There were, however, also small dogs introduced as family pets brought here and locally advertised for sale as early as the 1860s – “Miniature” dogs being popular. Small white dogs were popular in the late 19th to early 20th century. Circus shows with small white dogs were popular in the mid 19th century. Figure 1 shows a wagon load of small white dogs c. 1915, with a travelling dog circus at Trail, British Columbia. The first circus came to Victoria on September 16, 1860 (British Colonist 1860; Hammond 2000).

The American Eskimo dog, which is not an American dog, was developed from a small German and other European spitz breeds. They became known as the American spitz by 1910 and registered in 1913 as the American Eskimo spitz. They became very popular as the performing breed in travelling circuses and carnivals (Hajeski 2020) and in demand by the public as a family pet.

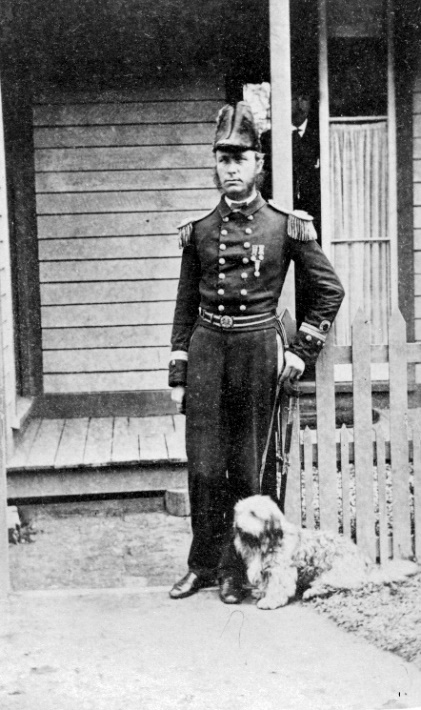

One “purebred spitz” named Muggins became famous as a mascot for the Canadian Red Cross during World War I (Hayter-Menzies 2021). Small dogs were common on Naval ships that visited Esquimalt in the 19th century. Figure 2, shows Lieutenant Daniel Pender and his dog in 1860.

Small white European breeds of dogs were common in early dog shows, as can be seen during a Duncan dog show on Vancouver Island on June 18, 1910 (Figure 3). Wool dogs were never registered for dog shows.

Characteristics of the wool dog

As I mentioned in an earlier article, not all wool dogs were white and not all of them were what we would consider small by todays standards (Keddie 1993), Cowlitz elders of Washington State, born in the 1830s, described to James Teit, the two types of dogs they remembered in their youth. The “Kaha” as a “sort of grey wooly or thick haired dog, straight ears, tail curled slightly used for hunting,” and the “Kimia” which is “about same size various colors browns and spotted whites they had finer longer hair and were sheared” (Teit 1910).

James Teit, who was married into the Nlaka’pamux First Nations and had extensive knowledge of the larger region in the Interior of British Columbia, interviewed an elderly Indigenous weaver at Spuzzum in the Fraser River Canyon, before 1908. She told him:

“the pure breed of Wool Dogs was totally extinct around Spuzzum from before she could remember, but that she had heard from the old people they were medium-sized dogs with long, very fine, thick hair. They were mostly white but some it is claimed were black. They were a distinct species according to tradition introduced from the Lower Fraser, and were to be found as far east as Lytton. The Indians tried to keep them from interbreeding with the real Interior dog, and around Spuzzum favoured the keeping of them. Their hair was used in blanket weaving in Spuzzum generally mixed with the wool of the goat. The using of dog hair it is said made the blankets a softer texture and further more they supplied a source of wool right at hand whereas the goats had to be hunted and their wool thus cost a considerable labor.

These dogs were much altogether a different species from the common dog of the Thompson further east and were called by the special name of x lît sel Ken. The other dog called SKaxaõé (viz real dog) somewhat resembles the ‘Husky’ and also bore some resemblance to the coyote and to the wolf with both of which they occasionally interbred. They were used mostly for hunting purposes” (Teit 1908).

When discussing blanket dyes, Teit notes: “The hair of black dogs was also used when obtainable viz black specimens of x lît sel Ken” (Teit 1908).

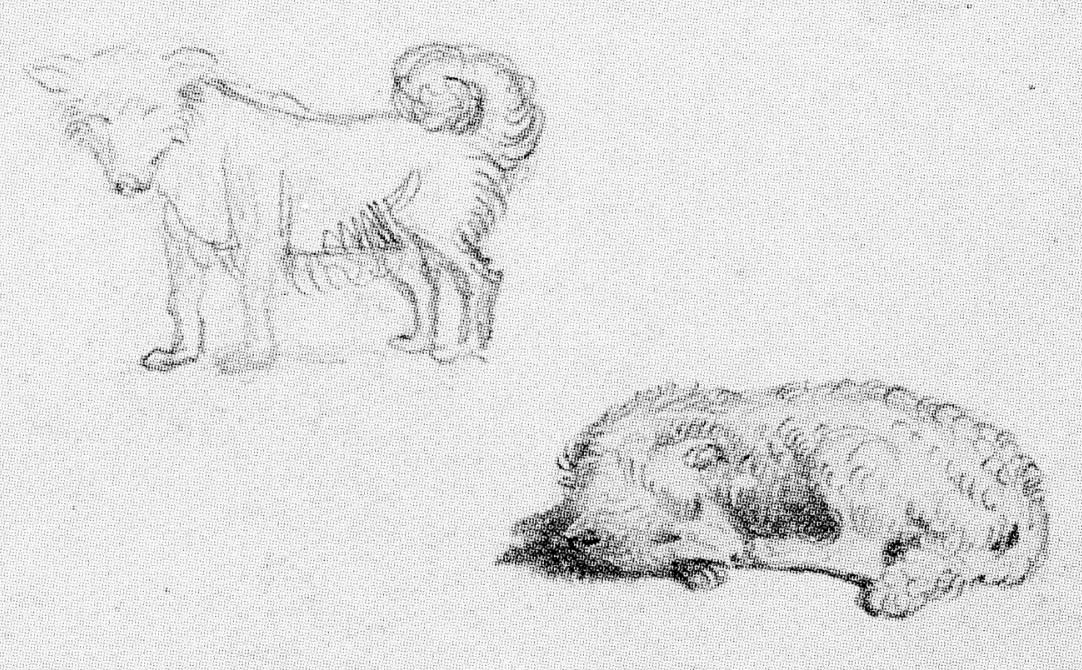

Paul Kane, who saw and drew the Wool Dogs in 1847, also described them as a: “small dog with long hair of a brownish-black and a pure white hair” (Kane 1859). Kane’s original drawings, as opposed to his paintings, show the more pointed mussels of the wool dogs (Figure 4).

John Keast Lord, the naturalist, suggested that these Wool Dogs: “pretty good size, and generally white, with much longer and softer hair…but having the same sharp muzzle and curling tail…”.

Galiano also notes the “moderate size” of the wool dogs while near Nanaimo in June of 1792: “These animals are of moderate size, resembling those of English breed, very woolly and usually white. Among other differences from those of Europe is their manner of barking, which is a mournful howl” (Jane 1930).

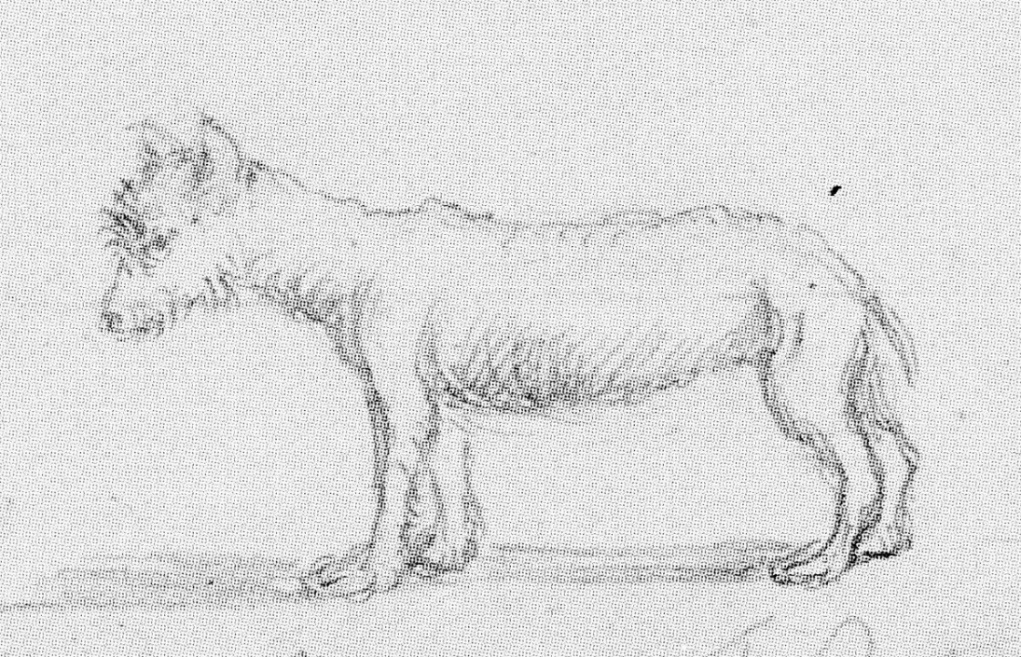

Figure 4a. shows Paul Kane’s 1847 drawings of two unsheared wool dogs from Vancouver Island and figure 4b, shows what appears to be Kane’s version of a sheared wool dog – not having the large up-curved tail. The latter can be compared with Figure 5, a faint pencil drawing by Montague Tyrwhitt-Drake, done in Victoria in 1859. In talking about the burial structures at Laurel Point in Victoria Harbour (Keddie 2019) Tyrwhitt-Drake mistakes the land otter-like creatures on one of the human figures: “The other is holding 2 dogs of a breed which I am afraid is lost to the present generation”. At the base of his letter, he does the sketch shown in figure 5. He does not specify what kind of dog it is in the drawing but in regard to the drawing says: “This is an unfinished sketch but you must take it as it is”. The sketch may represent a sheared wool dog or another type of dog,

It appears from the early descriptions that the wool dog was not much smaller than the common village dog. Although there may have been regional size differences. When Captain George Vancouver, was anchored near Restoration Point in Puget Sound, in 1792, he observed numerous dogs that: “much resembled those of Pomerania, though in general somewhat larger were all shorn as close to the skin as sheep…and so compact were their fleeces, that large portions could be lifted up by a corner without causing any separation composed of a mixture of a coarse kind of wool, with very fine long hair, capable of being spun into yarn”.

Pomeranian dogs, Figure 6, were much bigger in George Vancouver’s time in Britain. Vancouver would be aware of Pomeranian dogs as they became popular in his time. Two members of the British Royal family influenced the evolution of the breed just as Queen Elizabeth II has influenced the spread of Corgis today.

In 1767, Queen Charlotte, consort of King George III, brought two Pomeranians to England named Phoebe and Mercury. The paintings of the time depicted a dog that was larger than the modern breed. At the time the breed weighed as much as 30-50 pounds (14-23kg) but having the modern traits of a heavy coat, pointed ears and tail curled over its back (Vanderlip 2007).

The Pomeranian descended from a larger Spitz type dog. The earliest examples of the breed were white or occasionally brown or black. Queen Victoria owned a particularly small Pomeranian which popularized the smaller versions of today. During her reign the breed decreased by half its size.

In the 1840s, Alexander Anderson, while passing the many palisaded villages on the lower Fraser River with wool dogs, he observed their “bushy tail” and how “they differ materially in aspect from the common Indian cur, possessing however the same vulpine cast of countenance”. By this he was suggesting that they had more pointed mussels than many later breeds (1857).

Anderson from his early experience described the wool dogs as : “about the size of an Irish Water Spaniel …The general appearance of the animal, with its curled-up tail pointed nose and erect ears was that of a Pomeranian” (Anderson 1857).

When did the wool dogs become extinct?

It is difficult to be specific about the time when wool dogs became extinct. It appears that this happened faster in areas of European occupation and trading. But by 1860 they appear to no longer be visible and likely were bred out shortly after.

Dog Eating

Dogs were a favoured food of fur traders, which contributed to the reduction of dogs in general. As early as 1815, Franchere reports from the lower Columbia River: “They sold us four horses and thirty dogs, which were immediately slaughtered for food” (Franchere 1854).

In 1817, Ross Cox records from the Columbia River that his expedition group: “purchased twenty dogs for the kettle”. On the same trip he mentions: “There dogs are of diminutive size, and strongly resemble those of the Esquimaux, with the curved-up tail, small ears and pointed nose. We purchased numbers of them for the kettle, their flesh constituting the chief article of food in our holiday feasts for Christmas and New Year.” (Cox 1832).

In 1833, William Tolmie of the Hudson’s Bay Company, while in Hood Canal, “purchased a large woolly dog for 5 loads of powder and balls” for eating (Tolmie 1841).

Devalue of Blankets

The value of Indigenous wool blankets was greatly reduced by July of 1846. Berthold Seemann indicates that while at Port Discovery in Washington State: “They keep dogs, the hair of which is manufactured into a kind of coverlet or blanket, which in addition to the skins of bears, wolves and deer, afford them abundance of clothing. Since the Hudson’s Bay Company have established themselves in this neighbourhood, English blankets have been so much in request that the dog’s hair manufacture has been rather at discount, eight or ten blankets being given for one sea-otter skin” (Seeman 1853).

Two writers who commented on wool dogs in the 19th century, based on personal experience, were Alexander Caulfield Anderson (1814-1884) of the Hudson’s Bay Company and his son Robert James Anderson.

Alexander Anderson observed dogs throughout British Columbia, Washington and Oregon and published articles and wrote manuscripts on Indigenous cultures (1834; 1855; 1857; 1878). He observed: “These dogs were regularly bred for the hair they furnished and were quite numerous as late as 1849. With the increasing facilities for obtaining blankets & material of European manufacture so the necessity for keeping up the breed disappeared resulting in the course of time in its total extinction” (Anderson 1857).

By 1909, Robert James Anderson was compiling chapters for a book on Indigenous peoples of British Columbia (Victoria Daily Colonist1909). He compiled the manuscript with material from his father’s written material on “The Indians of British Columbia”. Robert Anderson wrote more of his own memoirs by 1920 when he was 79 years old. In commenting on the Old Songhees Reserve of his youth while attending the Fort Victoria school in the late 1840s, he noted:

“In this village were a great many of the small white woolly Indian dogs which have become extinct. …The Indian dogs would swim over the Indian village opposite the Fort and get after Mrs. [Roderick] Finlayson’s fowls, so of course, we naturally hailed the chance of exercising our cruelty by chasing and stoning the dogs, sometimes being lucky enough to corner one and kill him. To this day I look with regret on the horrid cruelty we were guilty of regarding these poor dumb animals. The dogs I refer to were handsome white animals resembling a Pomeranian but larger with long woolly hair which was regularly shorn and woven into blankets and articles of clothing, so that the dogs were of economic value to the natives and we were therefore doubly blameable (Anderson 1920; Colman 1951)

Robert James Anderson lived in north Saanich most of his life and worked on Reserve settlement claims. It would seem likely that he would have been aware of and have commented on any wool dogs that existed in the late 19th century.

Alexander Anderson wrote in 1855:

“These dogs no longer exist. They disappeared immediately after Forts Yale and Hope were built because the Natives of this part of the lower Fraser no longer had any need to weave their own blankets. But in some places the traditions lasted longer. The Cowichans, for example, had no access to the fur trader’s blankets and kept their Native craft going. Eventually they substituted wool for dogs’ hair, and knitted sweaters rather than weaving blankets” (Anderson 1855).

When George Gibbs visited the Neah Bay village in January 1855, he did not notice the making of dog hair blankets but noted that when Goldsborough visited the village in 1850, he observed in Flattery Jack’s longhouse that “about twenty women were busily engaged in making bark mats and dogs-hair blankets” (Gibbs, 1877) .

The historic observations suggest that raising dogs for making blankets was drastically reduced by 1855. The effects of the thousands of outsiders and their dogs during the gold rush period starting in 1858 would have reduced the wool dog populations. An important change occurred in the Cowichan region of Vancouver Island by 1860, when sheep were introduced and Scottish settlers taught local Indigenous people to switch some of their weaving skills to the knitting industry (Lane 1951; Stopp 2012).

The variation of Dog Characteristics

Elmendorf wrote in regard to the “wool dog” of the people living along Hood Canal: “The wool dog was a distinct breed and was not used for hunting. Wool dogs lived in the house with their owners and were given special care and a different diet from the hunting breed. Owners tried to prevent their interbreeding with hunting dogs” …Informants knew no specific details on the above points. The breed has probably been long extinct” (Elmendorf and Kroeber 1992).

The wool dog of George Gibbs that was killed and sent to the Smithsonian (see Barsh 2002; Solazzo 2011) was likely from a more peripheral area. Although Gibbs was working in the Chilliwack area, one possibility is that he obtained the wool dog when he was visiting the mouth of the Lillooet River on March 16, 1856. At this time he was developing a Indigenous vocabulary with chief K’Shaãn-ta of S’koots-mah village. The interpreter who accompanied him was the Sumas chief Skeh-uhl from the Chilliwack region (Gibbs 1863).

Given that Gibbs had a “wool dog” named Mutton, one would assume that he had a good perspective on the physical differences of Indigenous dogs. Yet he states: “Dr. Suckley considers the dogs to be of two breeds, One resembling the coyote, or prairied-wolf, and very probably crossed with that animal which is the kind used for hunting; the other, a long-bodied, short-legged, turnspit-looking cur, which is the property and pet of the women. To these are probably to be added a third, the dog used by the Skagit, Klallam, and others of the lower part of the Sound and Gulf of Georgia, which is shorn for its fleece.” (Gibbs 1877). In his word dictionary Gibbs only gives the various names for two dog types considered different: “Dog (the common kind), ko”bai, ko’mai, sko’bai (plur. Sko-ko-bai); the kind sheared for its fleece, ske’-ha (Nisk. (Niskwali), ska’ha (Skagit) (Gibbs 1877).

Other Small Dogs

Other smaller varieties of Indigenous dogs that were not wool dogs likely existed in the past on the southern coast of British Columbia. As Crockford et. al. say:

“Prince of Wales Archipelago dogs ranged in size as much as dogs from similar-aged coastal sites in southern British Columbia and western Washington. Small, wool-type dogs have an antiquity on the south coast of at least 4,000 years although they do not appear to be widespread and common until the most recent period, ca. 1000 bp to the late 1700s (Crockford et. al. 2011; Crockford and Cameron1997).

A close-up of dogs at a Gwa’sala Village on Cape Caution in Queen Charlotte Strait in 1873, can be seen in figure 8. This photograph has often been mistakenly described as being on the lower Fraser River. This village is part of the Kwakwaka’wakw Nations on the mainland opposite the North end of Vancouver Island and far north of the historic area where wool dogs were found among speakers of Salish languages. They are not wool dogs but have some of their general characteristics – being small with pointed ears and a curved tail over their backs. However, neither these or the more modern spitz bred dogs such as the Papillon in figure 9, have the wolf-like pointed mussels as described in the early accounts

There was, at least one dog in historic times that may have been related to the wool dog that was found among the Kwakwala speakers and possibly traded from the south in historic times. Franz Boas recorded the story from George Hunt:

“You asked me about the dog wool of the early Kwakiutl people. I saw one dog of a chief whose name was “ Great Mountain. Chief of Numaym — “and the name of the great short legged dog was Qalakwa. The hair of the dog was long like wool, and it hung down to the ground as he was walking about, and the hair was not very curly. The hair was very fine. His eyes did not show on account of the hair that covered them. It looked as though he had no feet, as he walked about.” … “at the end of the winter , the hair of the dog was cut and when this was done the women, the wife of Neg’adze, took the dog hair and washed it in running water. After she had done so, she hung it up for the water to drip off, and after all the water had dripped off, when it was not dry yet, she pulled it apart and pulled out the hairs singly and put them down lengthwise at the place where she was sitting. When all the hair had been pulled apart, the women took her spindle and her spinning box, and she put together three hairs of different lengths. The ends were even and she wound them around the spindle and she spun them. Now the hairs were twisted in the same way as is done with the nettle bark. When they were all twisted, they were woven into the yellow cedar bark blanket. If a man wears on his body a blanket with a hair braid, it is a sign that he is a chief, and when the braid is of mountain goat wool, then he is a common man. Now, all braidings of the cedar bark blankets are entirely of cedar bark, for I saw only one dog of this kind, when I was a little boy.” (Boas 1921).

Discussion and Conclusion

When reading historic documents on dog descriptions, it is important to know about the history of the specific dogs mentioned, as so many of the breeds have changed in size and other characteristic over the last 200 years.

It is also important to know about the people providing the information. Writers in the mid 1800s were often well read with sources of information from early explorers and scientists, from George Vancouver to biologist Dr. John Scouler in 1825. It was sometimes the practice to acknowledge the general assistance of other individuals or note whose books were read, but authors did not always credit earlier writers as sources for specific information that was not from their own observations. This resulted in the reader seeing multiple sources for some facts that were few in number or only one.

As an example, Scouler’s information which he credited to an earlier 1824 account (Young 1905) about putting wool dogs on small Islands, was used in statements of biologist John Lord in 1866, John Gibbs and others such as Jenness in later publications. This has evolved in recent times to mentions that it was a common practice to put wool dogs on small Islands.

Scouler’s 1825 statement only referred to Tatoosh Island: “the natives of Tatooch show much ingenuity in manufacturing blankets from the hair of their dogs. On a

little island a few miles from the coast they have a great number of white dogs which they feed regularly every day” (Scouler 1905).

E.C. Fitzhugh refers to dressing in “skins and blankets made of dogs hair and feathers” in Bellingham Bay in 1857, and Aylmer, about the same time, noted at the south end of Vancouver Island that: “Dogs are numberless, both in private and wild life, one peculiarly long-haired kind being bred for the sake of their fur, which is interwoven with frayed bark for blankets” (Alymer 1860). At a village inland from Nanaimo on Vancouver Island, Aylmer writes that there are garments made: “from various things, one, the most costly, of a native flax: another of bark and dogs hair; a third of goose down; and the last, and most common, of the fir-tree (cedar bark)” (Alymer 1860}.

In these latter cases it may be that the individuals are just repeating what they had read or had been told by others rather than being informed by local Indigenous people or having the knowledge to identify the material themselves.

The collection of one specimen of wool dog for a Museum collections in 1859 suggests that these were becoming rare at the time. Although an increasing number of Museum blankets are shown to contain dog hair their date of manufacture cannot be placed after 1860 (see Barsh et. al. 2002; Solazzo et. al. 2011 ).

The claiming of wool dog statis to small dogs via photographs dating from the 1890s to the 1930s is what I consider wishful thinking or nostalgia for the past when they lack any evidence of the context and specific information regarding the dogs shown.

Dogs clamed to be wool dogs are often too small, they lack the genetic spitz tail curving over their backs or have an absence of perky pointed ears on the top of their head. These are the typical wool dog characteristics noted by various observers from the 1790s to the mid 19th century. Claiming wool dog statis to floppy-eared dogs living dogs in Washington state and British Columbia should be taken with a critical eye.

In addition to the scattered genetic analysis that has been undertaken, there is a need for more full genome analysis on living dogs claimed to be wool dogs or taxidermy specimens that have information as to when they were created. More extensive DNA analysis of pre-contact bones will be necessary to show any regional variations and degrees of mixing with coyotes and wolfs.

Appendix 1

The photographs referred to as being images of “wool dogs”

There are ten photographs of three dogs that I will be referring to here. One image dates to between1895-1897, five on November 11, 1935, two in 1936, and another possibly of the 1940-50s period.

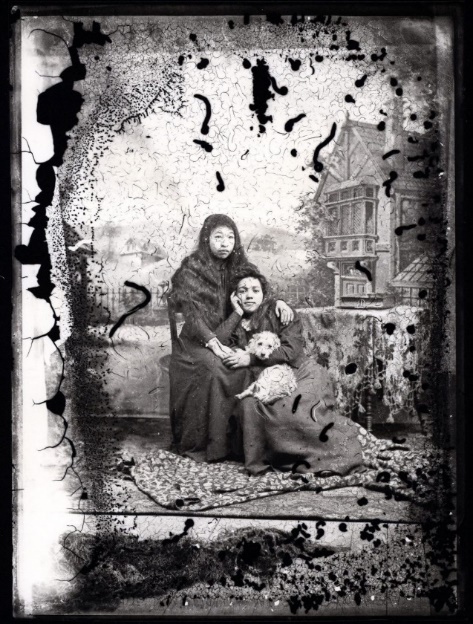

The Chilliwack Studio Dog

A photograph in figure 10 showing two indigenous women with a small white dog has been assumed to be a wool dog by several authors. This image was taken by photographer James O. Booen in his studio in Chilliwack, British Columbia, where he operated from 1895 to 1897.

Given the many anthropologists, surveyors and historians who visited this region since the mid 19 century and worked closely with Indigenous peoples, there would have been a record of the observation of wool dogs occurring after 1858. This would be especially true of Oliver Wells who helped revive the weaving industry and often consulted with elders in the Chilliwack region.

The dog in the photo of Booen may not belong to the two young Indigenous women show in the photo studio. The dog does not have the pointed ears of a wool dog and one can not tell if it has the genetic characteristic of the curved-up tail of the various spits dog breeds.

The Tsawout Reserve Dog

Seven photographs of a small white dog were taken in on the Saanich Tsawout Reserve, one of the W̱SÁNEĆ Communities on southern Vancouver Island, in 1935 and 1936. Five were taken by William Newcombe of the Provincial Museum in 1935 and two by anthropologist Diamond Jenness of the Canadian National Museum in 1936. Jenness worked with the Saanich with the object of writing a book on their history. It survives today as a few slightly different manuscripts and has now been published (Richling (ed) 2017). I have used the manuscript: The Saanich Indians of Vancouver Island (Jenness 1934-36).

In this manuscript, Jenness added a note after a brief mention of dog hair clothing: “The dogs that supplied this hair belonged to a small breed now extinct, though very numerous before the introduction of trade blankets destroyed their utility. During the sockeye and humpback salmon season the Indians commonly abandoned them on islands with whatever dried fish remained over from the winter; then they recovered them in the autumn and sheared them with mussel shell knives. In 1936 I noticed an old, creamy-white dog on the west Saanich reserve which seemed to carry some of the old strain; its owner had sheared it every autumn and sold the hair to a relative on the mainland, who knitted it into mittens)”.

Jenness did not state that the Saanich had claimed that it was a wool dog, only that, based on his own observation, he though this dog “seemed to carry some of the old strain”. I have talked to a number of non-Indgenous weavers in the general region who have to this day made blankets or capes from their own pets that are not wool dogs.

The dog in the figure 12 photo, was suggested as being a wool dog by the biologist McTaggart-Cowan because it was being sheared every year. The Jenness photographs, that McTaggart-Cowan obtained copies of, are part of the Ian McTaggart Cowan fonds AR514 Box 3, PN579, at the University of Victoria. They were recorded as taken at “Saanichton–East Saanich Indian Reserve”.

McTaggart-Cowan may have been influenced by his Provincial Museum colleague William Newcombe, who took five other photographs of the same dog the year before Jenness on November 30, 1935 (figure 13). These are located in the RBCM ethnology photograph collection as the old Newcombe catalogue series E1018a-XXII/34 to E1018e-XXII/34 and later series PN 5809a – PN5809b.

There is no recorded information from Indigenous people at the time saying this (figure 11) was a “wool dog”. It may have been an assumption on the part of McTaggart-Cowan or suggested to him as a possibility by Newcombe or Jenness.

This dog, clearly does not have the pointed ears or the spitz type tail curved up over his back as described in eye-witness accounts of wool dogs. The second photograph, figure 12, appears to be a sheared version of the same dog.

William Newcombe took five photographs on November 30, 1935 of a small white dog on the Tsawout Reserve in Saanich which he referred to as “Johnnie Claxton’s woolly dog”. Figure 13 shows different close-ups of the dog from the five photographs in the RBCM Newcombe collection.

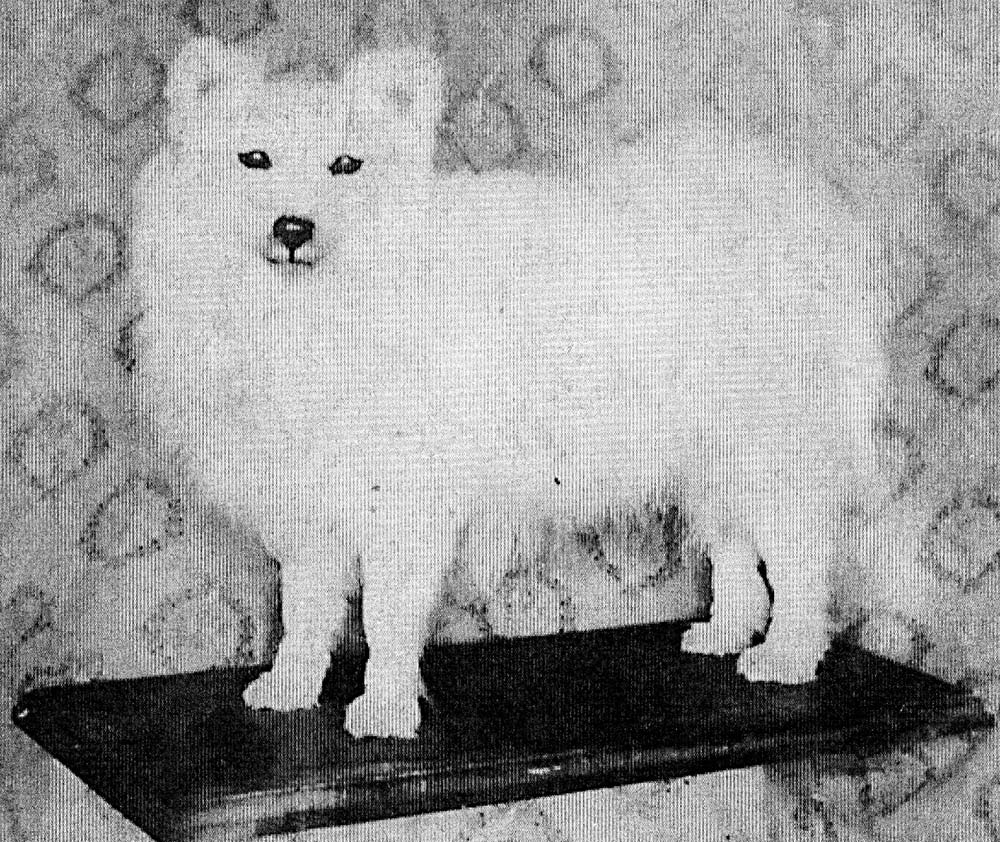

A Taxidermy White Dog

A taxidermy specimen of a small white dog of an unknown breed is shown below in figure 14. This photograph was first brought to my attention by Terrence Loychuk who has had a long interest in researching dog hair blankets and wool dogs.

The Taxidermist who did it appears to have been Nathaniel T. Wherry who died in Saanich on Oct 25, 1949 at age 72. (Married April 13, 1911 to Bertha Dell Williams who died Feb 26, 1948 at age 62).

Nathaniel’s son Ralph Wherry took over the business after his father died. A newspaper article of June 14, 1952 in the Victoria Sunday Times Magazine, indicated that Ralph Wherry was at the time, “the only taxidermist on Vancouver Island”.

References

Anderson, Alexander Caulfield. 1834. Memoranda Respecting Milbank Sound, Jan. 3, 1834. RBCM Archives Add. Mss. 559.Vol. 1, file 6.

Anderson, Alexander Caulfield. 1855. Notes on the Indian Tribes of British North America, and the Northwest Coast. The Historical Magazine 7(3):73-81.

Anderson, Alexander Caulfield. (1857). Some Notes for Captain Prevost Hill of Satellite. August 25, 1857. Cathlamet Columbia River. A.C. Anderson Correspondence Outward. RBCM Archive Add. Mss. 559. AC40/An3/M296.

Anderson, Alexander Caulfield. 1878. History of the Northwest Coast. RBCM Archives Mss.559, Vol. 2, file 3.

Anderson, Robert James. 1920. Notes and Comments on Early Days and Events in British Columbia, Washington and Oregon. RBCM Archives Mss.1912.V. 15, f 4.

Anderson, Robert James. 1909-1920. Indian Tribes of British Columbia. RBCM Archives Mss.1912. Vol. 16, file 1.

Aylmer, Captain Fenton. 1860. A Cruise in the Pacific. From the Log of a Naval Officer. Edited by Capt. Fenton Aylmer. In Two Volumes. Vol. II, Hurst and Blackett Publishers, London.

Barsh, Russel L., Megan Joan Jones, and Wayne Suttles 2002 History, Ethnography, and Archaeology of the Coast Salish Woolly-Dog. In Dogs and People in Social, Working, Economic or Symbolic Interaction, edited by Lynn M. Snyder and Elizabeth A. Moore, pp. 1–11. Proceedings of the 9th Conference of the International Council of Archaeozoology, Durham, August 2002. Oxbow Books, Oxford.

Boas, Franz. 1921. Ethnology of the Kwakiutl. In Thirty-fifth annual report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, 1913-1914, 43–794. Bureau of American Ethnology

British Colonist 1860. Dan Rice’s Great Show. September 18, Vol. 4, No. 57.

Colman, Mary Elizabeth. 1951. School Boy at Fort Victoria. The Beaver Dec. 1851:18-22. Outfit 282.

Cox, Ross. 1832. Adventures on the Columbia River. Including the Narrative of the Residence of Six Years on the Western side of the Rocky Mountains among various Tribes of Indians hitherto unknown together with a Journey across the American Continent. J. & J. Harper, New York.

Crockford, Susan J. 1997. Osteometry of Makah and Coast Salish dogs. Archaeology Press, Deptof Archaeology, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC

Crockford, Susan J.; . Madonna L. Moss, James F. Baichtal. 2011. PRECONTACT DOGS FROM THE PRINCE OF WALES ARCHIPELAGO. ALASKA Alaska Journal of Anthropology 9(1):49-64.

Crockford, Susan J., and Cameron J. Pye 1997. Forensic Reconstruction of Prehistoric Dogs from the Northwest Coast. Canadian Journal of Archaeology 21(2):149–153.

Elmendorf. William and A.L. Kroeber. 1992. The Structure of Twana Culture, With Comparative Notes on the Structure of Yurok Culture. Washington State University Press.

Franchere, Gabriel. 1854. Narrative of a Voyage to the Northwest Coast of America. In the Years 1811, 1812, 1813 and 1814 on the First American Settlement on the Pacific. Translated and edited by J.V. Huntington. Redfield Publishers, New York.

Gibbs, George. 1855. Pacific Railway Reports. Vol. 434. Report of Mr. George Gibbs to Captain McClellan, on the Indian Tribes of the Territory of Washington. Olympia, Washington Territory, March 4, 1854. Washington.

Gibbs, George. 1877. Tribes of Western Washington and Northwestern Oregon. Part II. In: Department of the Interior. U.S. Geographical and Geological Survey of the Rocky Mountain Region. J.W. Powell. Contributions to North American Ethnology, Vol. I. Washington: Government Printing Office.

Hajeski, Nancy. 2016. Every dog. A Book of over 450 breeds. Fireside Books. New York.

Hayter-Menzies. Grant. 2021. Muggins: The Life and Afterlife of a Canadian Canine War Hero. Heritage House Publishing Ltd, Sidney, British Columbia..

Jane, Cecil. 1930. A Spanish Voyage to Vancouver and the Northwest Coast of America: Being the Narrative of the Voyage Made in the Year 1792 by the Schooners Sutil and Mexicana to Explore the Strait of Fuca. London.

Jenness, Diamond. 1934-36. The Saanich Indians of Vancouver Island. Ethnology Division Archives, Canadian Museum of Civilization, Hull, Quebec Manuscript number 1103.6.

Hammond, Lorne. 2000. Circus History Part 1:The Circus Discovers BC. Discovery. Royal British Columbia Museum. News and Events, 28:4:1-2.

Kane, Paul. 1859. Wanderings of an Artist Among the Indians of North America From Canada to Vancouver’s Island and Oregon Through The Hudson’s Bay Territory and Back Again. Longman, Brown, Green, Longman, and Roberts, London.

Keddie, Grant. 1993. Prehistoric Dogs of B.C. Wolves in Sheeps’ Clothing? The Midden. Publication of the Archaeological Society of British Columbia, 25 (1):3-5, February 1993. ‘

Keddie, Grant. 2019. The Laurel Point Indigenous Burial Ground. Royal B.C. Museum Web Site, July 12, 2019.

Lane, Barbara S. 1951. The Cowichan Knitting Industry. Anthropology in British Columbia 2:14-27.

Leclerc, George Louis.1807. Buffon’s Natural History. Containing A Theory of the Earth. A General History of Man, of the Brute Creation, and of Vegetables, Minerals, and &c. &c. etc. etc. From the French Edition. With Notes by the Translator. In ten volumes. T. Gillet, Printer, London.

Lord, John Keast, 1866. The Naturalist in Vancouver Island and British Columbia. In Two Volumes. Richard Bentley, London.

Scouler, John. 1905. Dr. John Scouler’s Journey to N, W. America, Columbia, Vacouver & Nootka Sound. The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society. 6(1):54-75.

Richling, Barnett (ed). 2017. The W̱SÁNEĆ and Their Neighbours: Diamond Jenness on the Coast Salish of Vancouver Island, 1935. Edited and introduction by Barnett Richling. Oakville, Ontario: Rock’s Mills Press.

Seeman, Berthold. 1853. Narrative of the Voyage of H.M.S. Herald During the Years 1845-51. Under the Command of Captain Henry Kellett, R.N. C.B.; Being A Circumnavigation of the Globe, and three Cruises’ to the Arctic Regions in Search of Sir John Franklin. Reeves and Co., London.

Solazzo, Caroline, , Susan Heald, Mary W. Ballard, David A. Ashford, Paula T. DePriest, Robert J. Koestler & Matthew J. Collins. 2011. Proteomics and Coast Salish blankets: a tale of shaggy dogs? Antiquity 85 (2011): 1418–143.

Stopp, Marianne P. (2012). The Coast Salish Knitters and the Cowichan Sweater: An Event of National Historic Significance. Material Culture Review, 76, 9–29.

Teit, James. 1908. Letter to Charles Newcombe, January 8, 1908. Newcombe Family Papers. RBCM Archives Ms1077, vol. 5, folder 143.

Teit, James A. 1910. Salish Tribal Names and Distribution. June 10, 1910. Unpublished Manuscript in the Files of Franz Boas. American Philosophical Library. (Film 372, Roll 15) [RBCM Archives Additional Manuscript 1425, Reel A 246].

Tolmie, William Fraser. 1841. Vancouver Island Tribes. Journal of the London Geological Society 13. (B.C. Archives NW 910.6 R888) (And in California Farmer and Journal of Useful Sciences. (ed) Alexander Taylor, San Francisco 1962).

Young, F.G. 1905. (ed) DR. John Scouler’s Journal of a Voyage to N.W. America. Oregon Historical Quarterly 6:2:159-205.

Vanderlip, Sharon. 2007. The Pomeranian Handbook. Barron’s Educational Series. Hauppauge, New York.

Victoria Daily Colonist. 1909. Strang Customs of Indian Tribes of B.C. Victoria Daily Colonist, April 21.