By Grant Keddie

Introduction

The Lekwungen needed to be keen observers of the natural world of which they are part. Knowledge of bird behaviour was important not only to secure them as a source of food, but also to inform them about where the fish resources were.

Birds were an import feature of ceremonial and religious life which included everything from their display on clothing and masks, to the mimicking of bird behavior in dances, and their role as mythic ancestors. Bird names were given to months as both indicators of time or as important food sources in that month. Birds were imbedded in Lekwungen culture.

There are around 390 species of birds sighted in the Greater Victoria Region, many of these are rare visitors and most are too small to be considered as a food resources.

I will focus here on what is known about what birds were acquired for food in the past and how their body parts, such as feathers, skin and bones were used. In addition to current knowledge about local bird populations, I have used earlier recorded indigenous knowledge, early observations from non-indigenous visitors and from the bird bones found in archaeological sites. All photographs are the authors unless otherwise noted.

In the Lekwungen dialect of the North Straits Salish langage there are names for many individual birds that today are referred to as a species, as well as group names for similar looking birds or birds with similar behavior. Some are similar classifcations that may be used today, such as diving ducks and dabbling ducks (see Montler 1991). The Indigenous names of many small birds have been lost in time.

There are five different timing categories of birds in current use by ornithologists that Lekwungen people would have been generally aware of and illustrate the complexity of knowledge that was needed for survival over each year in the past.

There are: (1) resident species that nest in the area and were seen year-round. (2) Breeding non-residents that nest locally and winter elsewhere. (3) Non-breeding residence available three seasons of the year but winter elsewhere. (4) Birds that winter locally only. (5) Migrants in spring and fall often seen in large flocks.

The Archaeological Collections

Today, there are not enough large samples of bird remains collected from Archaeological sites in this region to tell a more complete story. In order to show how the quantity and proportions of bird species have changed over time we need to collect bird remains from seasonal sites, sites from different time periods and sites that cover a wide range of locations.

There were likely changes is the quantity and variety of bird species used over time. Birds that are identified as being rare or uncommon today may have been more common in the past. The fact that we are finding even small numbers of now rare birds in old sites suggests the latter is true.

This is clearly the case with the short-tailed albatross. Between about 2800 and 2000 years ago the large short-tailed albatross was a commonly eaten bird found at the Maplebank ancient village site, DcRu-12, located on the current Songhees Reserve. There is evidence at his site that albatross humerus and larger leg bones are being selected for the purpose of making bone artifacts. After about 500 A.D., the albatross was much less common and by the mid 19th century it was rarely observed (Crockford 2003; Crockford et.al. 1997). Although, it was reported to be “common” in Puget Sound Washington during the latter period (Prosch 1904). The more detailed historic decline has been documented by Cater and Spenser (2014). The earlier decline was likely related to environmental circumstance (see Stewart et. al. 2020).

Archaeological studies in other areas to the south in Washington, Oregon and California have suggested that Indigenous hunting in the past has played a role in reducing the population of larger birds and reducing the number of bird colonies (see Bovy et. al. 2019; Bovy 2007; Broughton 2004).

Many of the collected bird remains have not been identified to specific species. In the largest study, of almost 100,000 faunal remain, from the Maplebank site, 5.3% were bird remains. These included 63 bird species. The most common birds in this sample showed that all sizes of Gulls were important along with ducks and all the larger diving sea birds. (Stewart et. al. 2020).

Figure 2. Bird Concentrations

The Bird Resources

All varieties of larger birds were hunted and the eggs of larger nesting birds collected. Especially in the winter and during the spring migrations, tens of thousands of birds could be found in the Victoria Region. In 1857, Walter Grant notes the “vast variety” of aquatic birds: “They completely cover the lakes and inland saltwater lochs in winter, but altogether leave the country in summer” (Grant 1857). The next year James Bell notes an “abundance” of “ducks, geese, swans, and on the land, Grouse plentiful” (Ireland 1948). On October 9, 1858, Charles Wilson describes how duck, geese, cranes, and other birds all arrive “in myriads, so numerous indeed that when they are disturbed on the harbour, the flapping of wings can be heard a couple of miles off.” (Wilson 1866).

Frederick Whymper observed that the slaughter of “game” was happening at such an alarming rate that a Bill was presented on April 28, 1859, for the passage of an “Act for the Preservation of Game” making it unlawful to buy or sell game during certain periods of the year. This included “Duck, Teal, Goose, … Snipe or eggs ” from Feb. 1 to Aug. 1.

The effect of the introduction of the gun on bird populations and Indigenous hunting practices cannot be understated. In 1852, when James Swan went with 30 Quinault people past Point Grenville, Washington they stopped to have a “bird feast”. With the loaning of Swan’s gun to a Quinault man, he came back in an hour with “thirty half-fledged loons – which was the size of ducks, very fat – and five pelicans”. The women prepared them on ferns placed over hot rocks and ashes and covered them with mats to cook them in ½ hour (Swan 1870).

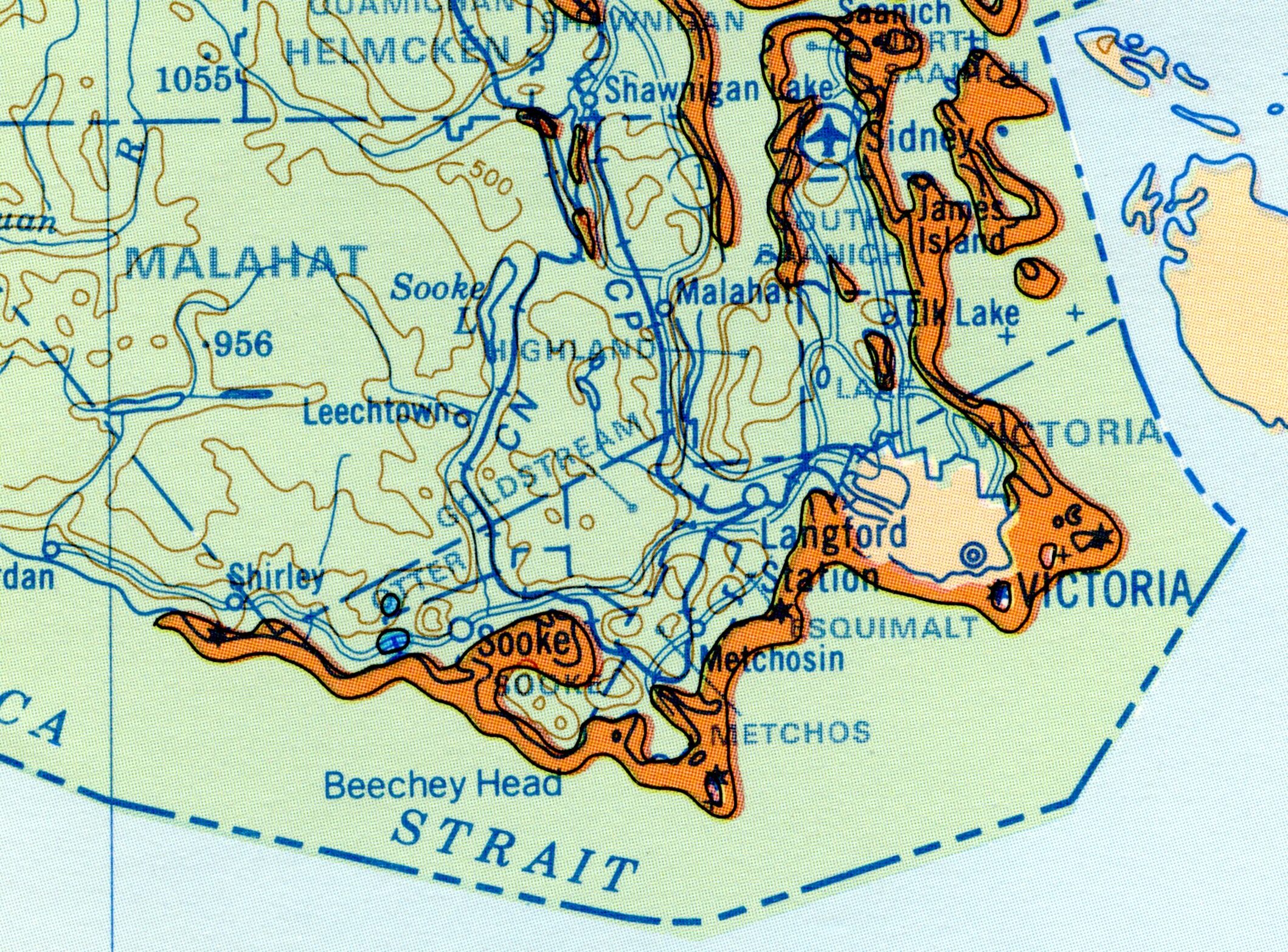

The south east corner of Vancouver Island is an exceptional region for bird habitat. Figure 2, shows the orange colour that represents: “Lands that have great importance for migration or for wintering waterfowl”, while the green areas are “Lands that have severe limitations to production of waterfowl” (Canada 1975).

Size Matters

The favourite bird prey of the Lekwungen would be the larger species. If a trumpeter Swan (Cygnus buccinator), weighing 10.94 kg., could be caught in the same amount of time, or even five times as long, as it takes to catch a Bufflehead duck (Bucephale albeola), weighing 0.42kg, the Swan would be a focus of attention.

Other large birds over 2kg in weight include the Tundra Swan (Cygnus columbianus), at 6.78kg; Canada goose (Branta canadensis) at 4.13kg; other medium size geese at around 2.65kg; the great blue heron (Ardea herodius) at 2.95kg; the Brandts cormorant (Phalacrocorax pencilitus) at 2.43kg; the Pelagic cormorant (Phalacrocorax palagicus) at 2.04kg; the Common loon (Gavia imera) at 3.40kg; Arctic loon (Gavia arctica) at 2.62 kg; some of the larger gulls and the Bald eagle (Haliacetus leucocochephus) at 4.65kg (all weights after Mitchell 1988).

Smaller birds, such as snipes, that can be captured in large numbers would be utilized when larger species were not available, during times of food shortage, or for the purpose of collecting their feathers in addition to eating. Because of their size the remains of smaller birds may not have preserved as well as the bones of larger birds in the old village sites.

The archaeological evidence shows that scoters, grebes, geese, sandhill cranes, loons and cormorants, grouse, pigeons and predator birds such as eagles and hawks were all consumed. Because of where and when birds were hunted the number of archaeological remains may skew the results in favour of specific species, especially those where hunting focused on nesting areas. The quantity of bones of a specific migratory species may vary withing a local region depending on which village was occupied during the spring or fall migrations.

The bird bones found in archaeological sites often cannot be identified as to species based on physical characteristics. This problem will be eliminated to a large extent with the development of inexpensive DNA and isotopic analysis.

Overview of the Birds Used by the Lekwungen

Cranes, Swans and Geese

The Lesser Sandhill Crane (Grus canadensis), flies over the Greater Victoria area today, only landing on rare occasions (fig. 3). However, their remains are found in ancient village sites and were more common in the past.

The bones of largest bird in the Greater Victoria region, the Trumpeter Swan (Cygnus buccinator), are rare (Fig. 4). The bird in resent times is fairly common in the area from November to the end of March. The Tundra Swan (Cygnus buccinator), is a rare visitor whose bones have not been found in ancient sites.

Of the six species of geese found in the region, bones of three have been found: Brant (Branta bernicla) (F.g.6), Canada Goose (Branta canadensis) (Fig. 5), and the rarely sighted Snow Goose (Chen caerulescens). Bones have not been found of the other three rarely seen: Emperor Goose (Anser canagic), Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons) and Cackling Goose (Branta hutchinsii).

Paul Kane, in 1847, observed the Indigenous use of goose skin for clothing: “The Men wear no clothing in summer and nothing but a blanket in winter, either of dog’s hair alone, or dog’s hair and goose down mixed, frayed cedar bark, or wild goose skin like the Chinooks” (Kane 2016).

Diving Birds

Birds referred to as Divers include loons, grebes and cormorants. In recent times they can often be found in modest numbers of 6-50 from Cordova Bay around the water front to the Victoria Breakwater. Cormorants have larger numbers in colonies from 20 to 185 on the Chain Islets, Harris Islet and Lewis reef.

Cormorants

The Lekwungen hunted three species of cormorants: Brandt’s Cormorant (Urile penicillatus), Double-crested Cormorant (Nannopterum auritum) and Pelagic Cormorant (Urile pelagicus) (Fig.7). The Double-crested is the most common one found in ancient sites.

Figure 7. Pelagic Cormorants (Urile pelagicus,) roosting on rocks in Esquimalt Lagoon, November 7, 2020.

Grebes

There are five species of grebes in the larger region. All are found in lagoon habitats and the Gorge Waterway. The pied-billed (Podilymbus Podiceps) (Fig. 9) has a widespread freshwater distribution and winters here from other areas. The Red neck grebe (Podiceps grisegena), and Horned Grebe (Podiceps auratus) (Fig. 8), are regular winter visitors with the Eared grebe (Podiceps nigricollis) rarely seen in Victoria. The western grebe is abundant in freshwater marshes in winter. Four are present to common in archaeological sites, except the eared grebe. Figure 8, shows a Horned Grebe eating fish off Tower Point in Metchosin and Figure 9, a Pied billed grebe on the Gorge.

Loons

The Red-throated Loon (Gavia stellata) and Yellow-billed Loon (Gavia adamsii) are common migratory wintering birds. The remains of the first, but not the second, have been identified in archaeological sites. The other two loons, Pacific Loon (Gavia pacific), and the larger Common Loon (Gavia immer) (Fig. 10) are present in Archaeological sites.

Ducks

The largest local Scoters average around 1.13kg (Fig.11), and the largest duck, the mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) (Fig. 1), weighs 1.18kg, but most ducks are under 1k g, ranging down to around 0.42kg.

In winter both diving and puddle ducks are found in numbers of 100 to 500 in the Cordova Bay to Cadboro Point area and both in larger numbers of 1000 to 5000 extending around to the Victoria Breakwater. Spring migrants of diving ducks from 100 to 500 are found in Esquimalt Lagoon but dabblers in much small numbers.

Winter migrants of dabbling ducks are more common at 100 to 500 birds than diving ducks at 50-100. Both varies of ducks at 6-50 in number can be found in the summer at Albert Head Lagoon (Stanley-Jones and Benson 1973).

In Portage Inlet both puddle and diving ducks include around 50-100 as Spring migrants. Of fifteen species of diving ducks known in the area today, only three have not yet been found in archaeological sites.

The common winter ducks include the Greater Scaup (Aythya marila)( Fig. 12); Lesser Scaup (Aythya affinis); Surf Scoter (Melanitta perspicillata) (Fig. 11); White-winged Scoter (Melanitta deglandi; Bufflehead (Bucephala albeola) (Fig. 13); Ruddy Duck (Oxyura jamaicensis) and the most abundant Common Goldeneye (Bucephala clangula)(Fig.14). The Ruddy duck and surf Scoter have not been found in old sites.

The ducks that are common throughout the year include the Long-tailed Duck (Clangula hyemalis); Hooded Merganser (Lophodytes cucullatus) (Fig.17); Common Merganser (Mergus merganser)(Fig. 16) and Red-breasted Merganser (Mergus serrator) – all found in old sites. The Black Scoter (Melanitta nigra), is uncommon and the Barrow’s Goldeneye (Bucephala islandica), an uncommon winter visitor but both have been found in old village sites

Dabbling Ducks

Dabbling ducks in Lekwungen territory seem to be less common in archaeological sites than diving ducks. This may be to some extent because most of the duck bones examined in the past have not been identified to the species level. Bird bones may have been deposited in different ways, such as small numbers of ducks being processed in the household over winter, as opposed to large numbers acquired at other times and mainly processed outside.

Bones of the uncommon migrant, Blue-winged Teal (Spatula discors), have been found as well as the very common mallard (Anas platyrhynchos (Fig.1)); the common American Wigeon (Mareca americana(Fig 24)); Northern Shoveler (Spatula clypeata)(Fig.23) and Canvasback (Aythya valisineria). Other birds whose bones are rarely found or not found include other wintering birds and summer residents: Wood Duck (Aix sponsa)(Fig.19); Cinnamon Teal (Spatula cyanoptera); Gadwall (Mareca strepera); Eurasian Wigeon (Mareca Penelope); Northern Pintail (Anas acuta) (Fig.18); Green-winged Teal (Anas crecca) (Fig. 21); Redhead (Aythya americana); Ring-necked (Aythya collaris )(Fig.22) and Tufted Duck (Aythya fuligula).

Local Migrations and Herring spawn eaters

In interpreting archaeological remains it is important to understand that there are shorter inter-local bird migrations and not just the larger Spring and Fall migrations of birds coming from long distances. Sea birds that depend on herring roe move for short periods of time within larger winter regions. These include vast flocks or rafts of sea-ducks like, Surf and White-winged Scoters, Black Scoters (rare in Victoria area), Greater Scaup, Long-tailed Ducks, Mergansers, and Goldeneyes. These rafts can contain as many as 13,000 birds. They all time their migration to coincide with the herring spawn (Lok et. al. 2008).

One study (1995-2002) examined the scale of aggregation of Harlequin Ducks (Histrionicus histrionicus), to seasonally and locally abundant prey at Pacific herring (Clupea pallasi) spawning sites in the northern Strait of Georgia. Aggregations of 3400–5500 birds gathered at a small number of sites along the same 8-km stretch of shoreline each year where spawn was available. Aggregations of the birds occurred in only a small fraction of the habitat area. Their stay at spawning sites averaged 2–3 weeks and many birds returned to their local wintering grounds afterwards. Birds moving to spawning sites represented 55–87% of the total wintering population. Few birds travelled farther than 80 km (Rodway et. al. 2003).

Seagulls Terns & Kittiwakes

Gulls range in size from small ones around 0.35kg to a medium size around 1.03kg and the larger ones to 2.27kg. The glaucous-winged gull once had colonies in Esquimalt Harbour and Trail Island. In historic times they shared the Chain Islets in the Oak Bay region with the Cormorants and Pigeon Guillemots. Gulls in the winter can be found in numbers of 100 to 500 in the Cordova Bay to Cadboro point area and in larger numbers of 1000 to 5000 extending around to the Victoria Breakwater. Gulls are found in Esquimalt Lagoon in numbers of 50 to a hundred.

Figure 29. shows large number of Gulls that collect around the mouth of Cecelia Creek at low tide.

The Black-legged Kittiwake (Rissa tridactyla), is rarely seen in recent years but has been found in two ancient sites in Oak Bay and Esquimalt harbour. This may suggest that they were more common in the past.

Ancient bones of “indeterminate” gull (Laurus species), where we can only say that the bone is from an unknown Gull, are very common in ancient villages around Victoria.

Ancient bones have been found of the more common gulls such as the Bonaparte’s Gull (Chroicocephalus Philadelphia)(Fig.27), Glaucous-winged Gull (Larus glaucescens)(Fig.26), Ring-billed Gull (Larus delawarensis), Short-billed Gull (Larus brachyrhynchus) and the less common Herring Gull (Larus argentatus), but no archaeological remains have been found yet of other common gulls: Iceland Gull (Larus glaucoides), Heermann’s Gull (Larus heermanni), California Gull (Larus californicus) and Mew gull (Larus canus) (Fig.25).

No ancient bones have been found of the rare migrants: Western Gull (Larus occidentalis); Glaucous Gull (Larus hyperboreus ); Sabine’s Gull (Xema sabini ); Franklin’s Gull (Leucophaeus pipixcan) and Black-headed Gull (Chroicocephalus ridibundus.)

No archaeological remains have been found of terns in the Victoria region. Only the Caspian Tern (Hydroprogne caspia) is common. Others, such as the Common Tern (Sterna hirundo), Arctic Tern (Sterna paradisaea) and Elegant Tern (Thalasseus elegans) are rare.

Auks, Murres, Puffins & Guillemots

The Common Murre (Uria aalge), which weights around 1 kg, has been found in several old village sites. The small Marbled Murrelet (Brachyramphus marmoratus), weights 0.23kg, and has also been found at old village sites, as has the Pigeon Guillemot (Cepphus columba). The Tufted Puffin (Fratercula cirrhata) (Fig.31), weighting 0.76kg, is rare but found in old sites. The rare Cassin’s Auklet (Ptychoramphus aleuticus), weighting 0.17kg, the Ancient Murrelet (Synthliboramphus antiquus) and Rhinoceros Auklet (Cerorhinca monocerata)(Fig.30), weighting 0.54kg, are common but not been found in old sites.

Mass Bird Mortality

Some species of birds such as Murres, Cassin’s auklet and Tuffed puffins occasionally faced mass mortality in the past. Figure 32, shows a dead Common Murre I photographed on Cannon beach Oregon, on September 16, 2013. It is estimated that nearly one million common Murres washed ashore dead from California to Alaska in 2015-2016. The die off was due to a long-lasting marine heat wave which caused a reduction in their food supply.

Warmer surface water temperatures off the Pacific coast—a phenomenon known as “the blob”—first occurred in the fall and winter of 2013, and persisted through 2014 and 2015. Warming increased with the arrival of a powerful El Niño in 2015-2016. With massive shifts in food availability, murre breeding colonies across the entire region failed to produce chicks for the years during and after the marine heat wave event (Piatt et. al. 2020; Bovy et. al. 2019).

How frequent these mass die-offs were in the past is not know. Although the reduction in the number of birds hunted would not have a great effect, the reduction of small fish, that other larger fish and sea mammals depended on, may have had a serious negative effect on the food supply, at least, on a short term basis. This situation, however, would provide an opportunity to collect large amounts of bird feathers and down without killing birds. The collecting of dead beach birds may also have affected biases in the Archaeological record (see Bovy et. al. 2019; Bovy 2002).

Albatrosses, Shearwaters, Storm-Petrels & Pelicans

The Short-tailed Albatross (Phoebastria albatrus)(Fig.33) was rare in recent times but is common in archaeological sites. The Black-footed Albatross (Phoebastria nigripes) is uncommon today, but may be included in some of the Phoebastria family bones that could not be identified as to species.

The uncommon Short-tailed Shearwater (Ardenna tenuirostris) and the rare migrant Sooty Shearwater (Ardenna grisea), have been found in archaeological sites. The three rarer Pink-footed Shearwater (Ardenna creatopus); Fork-tailed Storm Petrel (Oceanodroma furcate) and Leach’s Storm Petrel (Hydrobates leucorhous) have not yet been found in old villages, but might be included in the moderate number of shearwater bones that can not be identified to a species level.

The two pelicans, American White Pelican (Pelecanus erythrorhynchos) and Brown Pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis) are not common and have not been found in old villages.

Herons, Bitterns & Egrets

The Great Blue Heron (Ardea Herodias)(Fig.34), common in historic times, is found in a number of sites that also include artifacts made of their bones. Figure . shows one roosting in my back yard. The Green Heron (Butorides virescens) is a rare nesting resident, it and the rare Black-crowned Night-Heron (Nycticorax nycticorax) and American Bittern ( Botaurus lentiginosus), have not been found in old village sites, as is the case with the three species of Egret: Great Egret (Ardea alba); Snowy Egret (Egretta thula) and Cattle Egret (Bubulcus ibis).

Eagles, Hawks, Falcons, Ospreys & Vultures and Kites

There is not much information available from the early literature regarding the eating of predator birds such as hawks and eagles by Indigenous people, but the use of their feathers was likely of importance (see section on Feathers). In the Victoria area the bones of Bald Eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus)(Fig.35) are present in archaeological sites. No remains have been found of Turkey Vultures (Cathartes aura)(Fig.37), but the rare remains of Osprey (Pandion haliaetus)(Fig.36)and five species of hawks have been found at ancient village sites. These include: the more common Red-tailed Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis), Cooper’s Hawk (Accipiter cooperii) and Sharp-shinned Hawk (Accipiter striatus), but also the rarer Northern Goshawk (Accipiter gentilis) and Rough-legged Hawk (Buteo lagopus).

No Archaeological remains have been found for three rarer hawks, the Northern Harrier (Circus hudsonius), Broad-winged Hawk (Buteo platypterus),and Swainson’s Hawk (Buteo swainsoni), as well as the Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos).

The bones of unidentified Falcon species have been found but they could be from any of the four falcons that occur in small numbers: the Merlin (Falco columbarius), Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus) or, less likely, the rarer American Kestrel (Falco sparverius) or Gyrfalcon (Falco rusticolus).

Owls

The Great horned owl (Bubo virginianus) is the largest owl weighing on average around 1.59kg and is common in the area along with Barred Owl (Strix varia). The Barred owl, however, is a recent migrant to Vancouver Island and would not have been hunted by Lekwungen people. Figure 38,shows a Barred owl in my backyard in View Royal.

The bones of the very rare occurring Great Grey Owl (Strix nebulosa) have been found along with the rare Western Screech Owl (Megascops kennicottii) and Northern Pygmy-Owl (Glaucidium gnoma).

Bones were not found of any of the rarer Snowy Owl (Bubo scandiacus); Burrowing Owl (Athene cunicularia); Long-eared Owl (Asio otus; Short-eared Owl (Asio flammeus) and Northern Saw-whet Owl (Aegolius acadicus).

Small Shorebirds. Sandpipers & Phalaropes

There is sparce archaeological or ethnological evidence recorded at present for the use of these smaller birds, but it is likely in times of food shortages or for a diversity in food or feather preferences that they may have been captured. Larger shorebirds could be caught in beach snares. Small shorebirds that swarmed close together in large numbers could be caught in net trap. Suttles was told : “The little snipes that fly in clouds (leaser sandpiper?) could be killed just by throwing a four- foot stick into a flock” (1974).

Only the more common shorebirds that may have been hunted are included here. These include the Black Turnstone (Arenaria melanocephala)(Fig.39); Surfbird (Calidris virgata); Sanderling (Calidris alba); Dunlin (Calidris alpina)(40), Short-billed Dowitcher; Long-billed Dowitcher (Limnodromus scolopaceus); Least Sandpiper (Calidris minutilla); Western Sandpiper (Calidris mauri); Spotted Sandpiper (Actitis macularius), Wilson’s Snipe (Gallinago delicata); Common snipe (Capella gallinago) and Greater Yellowlegs (Tringa melanoleuca).

Pigeons, Doves, Coots and Rails

The Band-tailed Pigeon (Patagioenas fasciata) has been found in Archaeological sites. The less common Mourning Dove (Zenaida macroura) may have been used if its numbers were greater before the introduction of the gun.

The American Coot (Fulica americana)(Fig.41) is also found in old sites, but so far not the common seasonal Virginia Rail (Rallus limicola) and Sora (Porzana Carolina).

Oystercatchers & Plovers

The Black Oystercatcher (Haematopus bachmani)(Fig.42), is a common resident in this region and their bones have been found in old village sites. The Killdeer (Charadrius vociferus)(Fig.44) is also a common resident whose ancient bones have not found yet. The latter is also true of the seasonally common Black-bellied Plover (Pluvialis squatarola)(Fig.43) and Semipalmated Plover (Charadrius semipalmatus).

Grouse

Both Spruce grouse (Dendrogapus cnadensous) and Ruffed grouse (Bonasa umbellus)(Fig.45) are present in archaeological sites around Victoria. Robert Anderson who grew up in Fort Victoria in the 1840 and 1850s, noted how he: “hunted grouse and pigeon at Beacon Hill” (Colman 1951). Ernest McGaffey, who hunted grouse on Vancouver Island in the early 1900s, observed that Blue grouse were found in clusters of 5-8 or up to 25 (McGaffey 1910).

s

Woodpeckers & Kingfisher

The remains of unidentified small woodpeckers have been found in old villages. The most common bones identified to species are those of the Northern Flicker (Colaptes auratus)(Fig.47), and Belted Kingfisher (Megaceryle alcyon).

No remains have been found of the most common woodpeckers: Downy Woodpecker (Dryobates pubescens), Hairy Woodpecker Dryobates villosus) and Pileated Woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus)(Fig.46)or the less common Lewis’s Woodpecker (Melanerpes lewis), Red-naped Sapsucker (Sphyrapicus nuchalis), and Red-breasted Sapsucker (Sphyrapicus ruber).

Some woodpeckers are large enough to eat but they are likely to have been collected for their bright colored feathers, especially the red feathers of the large piliated woodpecker and the red—shafted flicker and the blue feathers of the Kingfisher (Fig.48)and Steller Jay (Fig.49) (see section on feathers.)

Jays, Crows & Ravens

Remains of the Steller’s Jay (Cyanocitta stelleri), which alive only weighs 0.1- 0.14kg, have been found in old villages but not the less common Blue Jay (Cyanocitta cristata). The bones of both the Northwestern Crow (Corvus caurinus) and the Common Raven (Corvus corax), are present in sites in the region. These birds, that are often part of local mythology, may have been hunted for just their feathers, but the Northwest crow weighs as much as a small duck and would be of a substantial enough size to eat at 0.34-0.44kg and more so with the Raven at 1.47kg. A future study of the cut marks on ancient bones will help determine if these birds were eaten.

Feathers, Skin and Bones

Bird parts such as skulls, beaks, wings, feathers and bird down were carried as charms associated with special spirit powers and formed a part of ceremonial use. Feathers were used on masks, headdresses, clothing and many small ritual objects.

Feathers were used for fletching arrows, the Indigenous explanation of the use of specific feathers was because they were water proof. Eagle, goose, and cormorant feathers were used. Saanich consultants said eagle feathers were best and Samish said cormorant feathers were best (Suttles 1974). Elles was informed that the feathers of the eagle, hawk and redheaded woodpecker were used for fletching arrows and in the headbands used in the tamahnous ceremony. Also: “A piece of the Kingfisher skin where the tail or wing feathers entered it was formerly used in fishing, attached to the line near the hook, as it was superstitiously supposed that it would attract the fish” (Elles 1985).

Women plucked waterfowl and mixed the down with twisted pieces of goose skin and stinging nettle fibre twine to make a textiles used for shirts and robes.

On the southern coast the down was stored in a bag made of a swan skin. The down of swans and eagles was worked into dog wool while it is being spun for making a fleece. (Stern 1934).

In 1906, John Humphreys of the Chemainus Band and Charles Newcombe were discussing making plaster models of an Indigenous man and woman for an exhibit at the Provincial Museum. Newcombe wanted to know about the traditional clothing that would have been worn before they acquired European clothing. Humphreys spoke the Halkomelem language fluently and: “After having visited a great many old Indians and having talked to them about the clothing worn by the Indians in early days I think that I am now in a position to suggest the kind of principal garment worn by the Indians while at home was a Clok [cloak] made of mountain goats wool of a very fine weave, next came a Clok made of birds feather, mostly seagull feathers, but sometimes the feathers of birds of more brilliant plumage was used. These were made into ornamental Cloks and were extremely valuable”. Humfreys explained that these were worn “in those day, about 1835 A.D.” (Humphreys 1906).

Even though Humphreys was talking about clothing of the Cowichan, Chemainus and Nanaimo that he was familiar with, it is likely these same clothing would have been worn by the Lekwungen. Feather cloaks were known among the Indigenous cultures of Puget Sound where in winter, women wore a blanket of goose skin, in strips netted together with the feathers on the outside.

Edward Curtis describes: “Another downy blanket was manufactured with much labor from the skins of waterfowl. The course feathers having been plucked, each down-covered skin was removed and carefully cut into a single long, half-inch strip by working around and around down the edge of the centre. Wound spirally on a pole, the skins as they dried could shrink only laterally, and shrivelled to mere cords covered with down, which were then turned into a plain-woven robe. The white skins of gulls were used for the body of the garment and black skins for a decorative border.” (Curtis 1913).

Among the Chinook on the Columbia River in 1792, Broughton noted: “The natives differed in nothing very material from those we had visited during the summer [on Puget Sound], but in the decoration of their persons. In this respect they surpassed all the other tribes, with paints of different colors, feathers and other ornaments. In the mythology there are examples of feather headdresses and the use of the heads of the red-headed woodpeckers heads on bows. Robes were made from the “strips of skin of wild fowl. These strips were either twisted or simply allowed to dry; … The strips of skin were sometimes wrapped round a string to give them additional strength (Lewis 1906).

Orange coloured, Red shafted flicker feathers and woodpecker scallops were of special importance to many peoples from Alaska to California. The Nisga’a wore flicker feathers attached to some headdresses: “The noble men and women might wear the headdress with frontlet mask. Carved and inlaid with haliotis to represent the crest, surmounted by flicker feathers and sea lion whiskers, and training ermine down the back” (de Laguna 1995). The importance of flicker feathers is described in a Haida story called: The Canoe People with Headdresses. It involved people with supernatural powers traveling in a canoe: “As they floated along, when they found any feathers floating about, they put them into a small box. If they found flicker feathers floating about, they were particularly pleased and kept them”(Swanton 1905). As the story shows the bird does not need to be killed to obtain feathers. On several occasions, I collected flicker feathers from the woods for indigenous artists, where a predator bird had killed a flicker and scattered its feathers (Figure 50).

Humming birds were caught by putting sticky tree sap or slug slim on branches near their nests. The humming bird skins were attached to clothing. Especially the clothing of children.

There are numerous feathers that can be seen in historic photographs, but identifying what is traditional can be a problem. Historic changes need to be taken into consideration, such as the common modern use of painted chicken feathers. De Laguna’s comments from Tlingit people are of interest here: “The bunch of feathers, stuck into a turban made of a black silk handkerchief would around the head, was admittedly copied from hackles on the Scottish bonnets worn by many of the Hudson’s Bay Company men. This headdress was worn by Tlingit men and women in ceremonies in the 19th century, and the bunch of dyed chicken feathers was called (in English), ‘Canadian feathers’ (de Laguna 1993).

The Cultural Use of Bird Bones

There are many human modified bird bones found in archaeological sites on the southeastern coast of British Columbia. These often do not have any known historical equivalent in their use. The ones with pointed ends shown in figure 51, were likely used as fine awls in the making of clothing. Some of those with holes were likely used as various kinds of whistles, flutes or the smaller ones used as toggles for bag flaps or needle cases. The one near the middle with the engraved design may have been used as a needle case. Only one example of a bone tube containing needles has been found on Vancouver Island. The latter was reburied and not available for comparison. Similar items were known among the Innit and cultures on the west side of the North Pacific.

Some bird bone tubes were worn as hair ornaments, in historic times, further south along the Columba River. Others were used as sliding protectors on small mammal traps (see Keddie 2019).

The Procuring of Birds

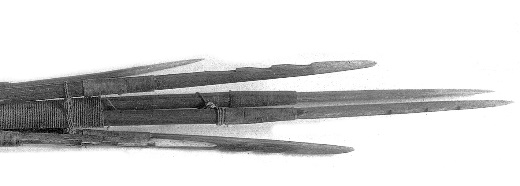

Bird hunting by the Lekwungen would have involved the use of several types of underwater and above ground nets, bird spears, bird arrows, slings, bone snares and bone trolling hooks.

Underwater Bird Nets

As herring spawn represents an important food source for many marine birds during late winter and spring, they can be easily caught by using underwater nets. The mid Gorge Waterway was an important location for this activity where the diving birds went after the herring spawn on the eel grass.

A net was stretched horizontally and set at an angle about a meter above the bottom of the sea in areas where herring spawned on the eel grass. When birds dove down to eat the herring ova they became emmeshed in the net and drowned. The bottom was held down by stone net weights (Suttles 1974).

The birds that focused on herring ova or eggs included the diving birds – Surf Scoters, White winged Scoters, American Scoters, Scaup, and Old Squaw, American Golden-eye and Bufflehead ducks (Munro and Clements 1951).

Above Ground Non-Drop Nets

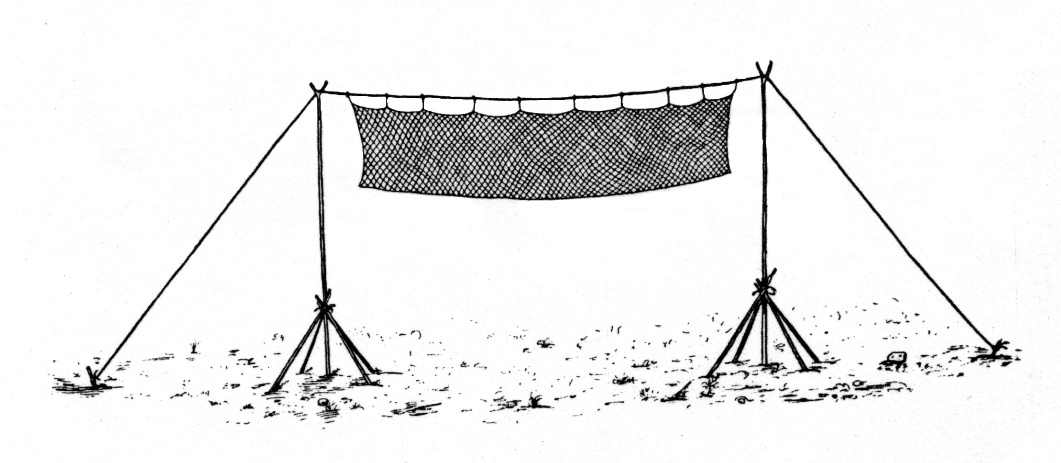

The poles of large above ground non-drop nets were observed in use outside of Lekwungen territory in the 1790s, such as on Sookie spit. These poles supported large nets which were stretched across a stream or channel, placed on a sand spit, or near a lake or swamp. Some nets could be drawn from one side to the other. During dawn or dusk when visibility was limited, ducks would be scarred up and get entangled in the nets which were dropped down to hold them long enough to be clubbed (Barnett 1955).

When John Humphries described these poles they were still standing at the mouth of the Chemainus River and one was still standing unused in 1928. Figure 52, shows the one last pole photographed by G.D. Sprott in 1928.

In 1866, Captain Wilson describes nets that were not dropped (Fig.53): “Across the entrance of small streams, or ‘slues’, to which wildfowl resort, long poles are erected at certain intervals, between which nets are spread; at night, fires are lighted at the foot of the poles, which frightens the water fowl, who flying toward the light, come in contact with the nets and fall down to the ground, where they fall an easy prey to the expectant Indians” (Wilson 1866).

Lekwungen consultants had a tradition that there was one of these nets at Swan Lake but did not know the specific location. I would suggest that this location was likely at the east end of the lake on a ridge that extends toward the lake. This is a place where birds fly in and out today. A large number of stone projectile points have been found behind this ridge which indicates, at least a seasonal use of this specific location over a long period of time.

Above Ground Drop Nets

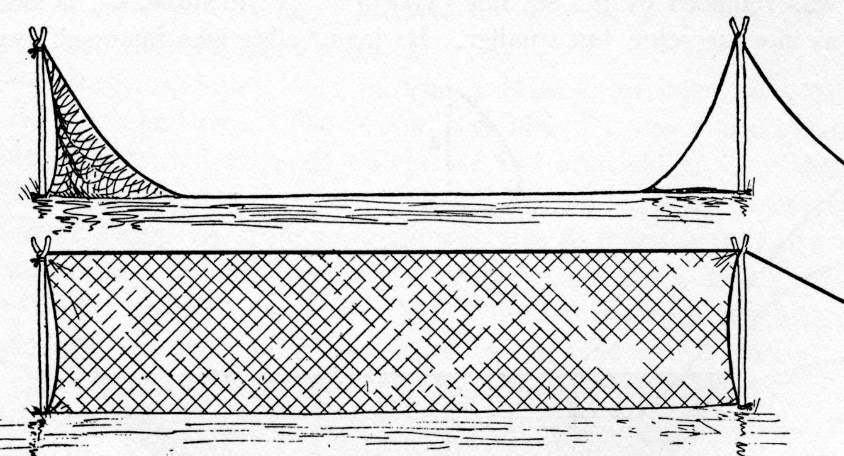

In 1905, John Humphries of Chemainus describes the drop net set up as follows:

“Standing part passes through all rims on the net & is also fastened to bottom of one upright like a mast with rings for a sail, which keep it in close contact. The hoist is separate & is made fast to the top ring & the bottom & passes through a withe of young cedar. The post used to be 80 to 100 ft high & were placed at the mouths of streams & places where ducks used to fly” ((Humphries 1905).

Suttle’s consultants also mentioned a ring that a rope was passed through at the top of bird net pole (1951). One of these may be like the RBCM artifact DcRv-Y:8 which was found hanging in a tree (see Keddie 2011).

Figure 54, shows two positions of a drop net. One shown up in front and one shown down in background.

Hunting with Firelight

Birds were also caught using fire as an aid. Two men paddled out at night to a place where two currents met and where waterfowl usually rested or on still lakes or inlets. A small fire in the canoe was kindled in a clay filled box. The light from the fire caused the ducks to swim into the shadow in front of the bow of the canoe where they were easily caught. Some people used a hand net which they threw over the birds. Others used a club and a special bird spear 2m to 3m long with two to five long barbs (Barnett 1955).

The most detailed account of this was provided to Franz Boas for hunting geese:

“A fire is built on a clay-covered board in the stern of the canoe. The steersman sits in front of the fire, and holds in his mouth a stick to which a mat is attached. This serves as a screen, by means of which the geese are kept in the light and the canoe in the dark. When the hunters approach a flock of geese from a distance, they first screen and uncover the fire a few times. At first the geese are scared away by the flare of the light, but gradually they get accustomed to it. Then the canoe approaches quickly and cautiously. As long as the geese are kept in the light, they cannot see the dark canoe, and it is possible to come quite near to them. They always swim in a direction at right angles to the rays of the light. One of the hunters stands quietly in the bow of the canoe and holds a net which is about two metres square, with meshes about 10cm wide, and is stretched tightly over a frame. It has a handle, with which it is thrown over the birds. When the net falls over the flock of birds, the hunters paddle quickly so as to bring the canoe over the net. They then take hold of the geese and twist off their heads. Wet dark nights are best for this kind of hunting.” (Boas 1909).

This practice of hunting birds with a screen in the boat was still being practiced in 1884-1885, but with the use of guns. Midshipman Bertran Mordaunt Chambers (later Admiral) while stationed in Esquimalt Harbour on the H.M.S. Satellite observed:

“As the rivers and lakes froze up the ducks began to frequent the harbour and the Indians prowled about in their canoes with old muzzle-loading guns and big piles of green stuff in the bows as shelter stalking the water-fowl.” (Chambers 1927)

Bird Spears

Special bird spears with multiple barbed points were used (Fig.55). For more detail, see Keddie, Bird Spears and Bird Arrows (2023).

Bone bi-points or Gorges

It was a common practice for many populations along the coast from Alaska to California to catch birds by trolling behind a boat using a bone or hardwood gorge. These are often called bi-points, as they are small, straight pieces of bone, wider in the middle that taper to a sharp point on both ends (Figure 56). Sea gulls, shearwaters and other off shore birds were a common prey with this technology.

Bird Nooses

Many small birds were caught with noose snares. Suttle’s Indigenous collaborators specifically singled out “marsh ducks”. Grouse were caught in snares while feeding on crab apples near swamps in the fall (Suttles 1951). I have observed crab apples growing in profusion along upper portions of Colquitz Creek.

The bird noose snare shown in figure 56, was purchased from Indian Agent Cox by Lt. George Emmons and donated by Emmons to the Provincial Museum of British Columbia July 16, 1923. The original tag has: Snare for small birds. Barkley Sd [Sound] V.I. [Vancouver Island].

References

Barnett, Homer. 1955. The Coast Salish of British Columbia. University of Oregon. The University Press, Oregon.

Boas, Franz. 1909. The Kwakiutl of Vancouver Island. Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History. Publications of the Jessup North Pacific Expedition Vol II, Pt II. E.J. Brill New York.

Bovy, Kristine M., Madonna Moss, Jessica E. Watson, Trances J. White, Timothy T. Jones. 2019. Evaluating Native American Bird Assemblage Variability along the Oregon Coast. The University of Rhode Island. Sociology & Anthropology Faculty Publications.

Bovy, K. M. 2002. Differential avian skeletal part distribution: Explaining the abundance of wings. Journal of Archaeological Science 29:965-978.

Bovy, K. M. 2007. Prehistoric human impacts on waterbirds at Watmough Bay, Washington, USA. Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology 2:210-230.

Broughton, Jack M. 2004. Prehistoric Human Impacts on California Birds: Evidence from the Emeryville Shellmound Avifauna. Ornithological Monographs, No. 56. University of California Press.

Canada 1975. Canada Land inventory. British Columbia. Land Capacity for Wildlife-Waterfowl. Environment Canada Lands Directorate.

Carter, Harry R. and Spenser G. Scaly. 2014. Historical Occurrence of the Short-tailed Albatross in British Columbia and Washington. Wildlife Afield 11(1):24-38.

Chambers, Admiral Bertran Mordaunt. 1927. Salt Junk Naval Reminiscences, 1881-1906. Admiral B.M Chambers C.B. London Constable & Co Ltd.

Colman, Mary Elizabeth. 1951. School boy at Fort Victoria. The Beaver. December 1951. Outfit 282:18-22. Crockford, Susan, Gay Frederick and Rebecca Wigan. 1997. A humerus story: Albatross element distribution from two northwest coast sites, North America. Journal of Osteoarchaeology. 7:378.1-378.1.

Crockford, Susan, Gay Frederick and Rebecca Wigan. 1997. A humerus story: Albatross element distribution from two northwest coast sites, North America. Journal of Osteoarchaeology. 7:378.1-378.1.

Crockford, S. 2003. The archaeological history of Short-tailed Albatross in British Columbia: a review and summary of STAL skeletal remains, as compared to other avian species, identified from historic and prehistoric midden deposits. Unpublished report submitted to CWS, Environment Canada, March 2003. 104 pp.

Curtis, Edward. 1913. The North American Indian. Volume 9: The Coast Salish Tribes, Chimakum, Quilliute, and Willapa, New York.

de Laguna, Fredrica 1995. The Tlingit Indians. George Thorton Emmons. Edited with additions by Fredrica de Laguna and a biography by Jean Low.

DePuydt, R. T. 1994. Cultural implications of avifaunal remains recovered from the Ozette Site. In Ozette Archaeological Project Research Reports, Volume II, Fauna (S. Samuels, ed.):197– 264. Department of Anthropology Reports of Investigation 66. Pullman: Washington State University.

Eells, Myron. 1985. The Indians of Puget Sound. The Notebooks of Myron Elles. Edited with an Introduction by George Pierre Castile University of Washington Press, Seattle.

Ernest, Bill. 1977. British Columbia Fish and Wildlife Branch. Southern Vancouver Island Wildlife Resources map. Assembled by Bill Ernest.

Grant, Walter C. “Reporting on Vancouver’s Island. Oct. 25, 1849. To James Douglas Acting Governor Ft. Victoria”. (BCARS A/B/20/G76).

Humphreys, John. 1904. In: Newcomb Family. Salish Notes. Additional Manuscript 1077. Vol. 57, folder 2. Series B: Ethnological. Correspondence with John Humphreys. Letter to Charles Newcombe June 21, 1904.

Humphreys, John. 1906. A History of the Cowichan Indians. As told by the Indians Themselves. Letter of March 8, 1906 to Charles Newcombe. RBCN Archives F/3/H88.

Ireland, Willard. 1948. Gold-rush Days in Victoria, 1858-1859. A letter fromJames Bell, edited with an Introduction by Willard E. Ireland. British Columbia Historical Quarterly. Vol. XII, No.3”231-246.

Ireland, Willard. 1953. Captain Walter Colquhoun Grant: Vancouver Island’s First Independent Settler. British Columbia Historical Quarterly, Vol. XVII, Nos. 1 and 2. January-April, 1953, pp. 87-126.

Jenness, Diamond. c. 1934-35. The Saanich Indians of Vancouver Island. Field Notes. Canadian Museum of Civilisation, Ms #1103.6.

Kane, Paul. 2016. Wanderings of an Artist Among the Indians of North America by Paul Kane, edited and with an introduction by Kenneth Lister. Royal Ontario Museum Press, Toronto.

Keddie, Grant. 2019. Bird Bone Tube Snare Guards in the Archaeology Collection of the Royal B.C. Museum. Royal B.C. Museum Web site and grantkeddie.com.

Keddie, Grant. 2011. Disc-Shaped Stones. The Midden. Journal of the Archaeological Society of British Columbia. 43:4:8-9.

Lewis, Albert B. 1906. Tribes of the Columbia Valley and the coast of Washington and Oregon. Vol. 1, Issue 1-6.

Lok, Erika K., Molly Kirk, Daniel Esler and W. Sean Boyd. 2008. Movements of Pre-Migratory Surf and White-Winged Scoters in Response to Pacific Herring Spawn. Waterbirds: The International Journal of Waterbird Biology. Vol. 31:3:385-393).

Mason, Otis T. 1895. The Origins of Invention. A study of industry among primitive peoples. Walter Scott, London.

McGaffey, Ernest 1910. Blue grouse shooting on Vancouver Island. Man-to-Man magazine, 6:9:799-801.

Mitchell, Donald 1988. Changing Patterns of Resource Use in the Prehistory of Queen Charlotte Strait, British Columbia. In: Research in Economic Anthropology, Supplement 3:245-290. JAI Press Inc., Grenwich, Connecticut.

Montler, Timothy. 1991. Saanich, North Straits Salish. Classified Word List. Canadian Ethnology Service Paper No. 119 Mercury Series. Canadian Museum of Civilization.

Munro, John A. and W.A. Clements. Water Fowl in relation to the Spawning of Herring in British Columbia. The Biological Board of Canada Under the control of The Minister of Fisheries. Bulletin No. XVII.

Moss, Madonna L. 2007. Haida and Tlingit use of seabirds from the Forrester Islands, southeast Alaska. Journal of Ethnobiology 27(1):28-45.

Prosch, Charles. 1904. Reminiscences of Washington Territory. Scenes, Incidents and Reflections of the Pioneer Period of Puget Sound. Seattle. In: Readings in Pacific Northwest History. Washington 1790-1895. Edited by Charles Marvin Gates, Published by the University Bookstore, Seattle, Washington. 1941.

Piatt John F, Parrish JK, Renner HM, Schoen SK, Jones TT, Arimitsu ML, Kathy J. Kuletz, Barbara Bodenstein, Marisol Gracia Reyes, Rebecca S. Duerr, Robin M. Corcoran, Robb S.A. Kaler, Gerald J. McChesney et.al.et al. (2020) Extreme mortality and reproductive failure of common murres resulting from the northeast Pacific marine heatwave of 2014-2016. PLoS ONE 15(1): e0226087.

Rodway, Michael S., Heidi M. Regehr, John Ashley, Peter V. Clarkson, R. Ian Goudie, Douglas E. Hay, Cyndi M. Smith, and Kenneth G. Wright, 2003. Aggregative response of Harlequin Ducks to herring spawning in the Strait of Georgia, British Columbia. Canadian journal of Zoology, vol.81:3.

Sanger, G.A. 1972. The recent pelagic status of the Short-tailed Albatross (Diomedea albatrus). Biological Conservation 4(3):189-193.

Sherburne, J. 1993. Status report on the Short-tailed Albatross Diomedea albatrus. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Anchorage, Alaska. 32 pp.

Stanley-Jones, Christopher V. and W. Arthur Benson. 1973. (Editors). An Inventory of Land Resources and Potentials in the Capital Regional District. A report to the Capital Regional District. A Co-operative Report Comprising Narratives and maps by British Columbia Land Inventory (C.L.I.), Pacific Forestry Research Centre, Canadian Forestry Service Soil Survey Section, Canadian Department of Agriculture.

Stern, Bernhard J. 1934. The Lummi Indians of Northwest Washington. Columbia University Press.

Stewart, Kathlyn M., Grant Keddie, Scot Rufolo, Rebeca Wigen, Susan Crockford and Andree Blais-Stevens. 2020. The Maplebank Site: New Findings and Reinterpretation on the Late Holocene Pacific Northwest Coast. The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology. 15-264-283.

Suttles, Wayne. 1974, The Economic Life of the Coast Salish of Haro and Rosario Straits. In: Coast Salish and Western Washington Indians 1, pp. 116 & 132. Garland Publishing Inc., New York.

Swan, James A. 1870. The Indians of Cape Flattery, at the Entrance to the Strait of Fuca, Washington Territory. Smithsonian Institute. Contributions to Knowledge, No.220, 16 (8):1-105.

Swan, James G. 1966. The Northwest Coast. With an introduction by W.A. Katz Ph. D. Ye Galleon Press, Fairfield, Washington.

Swanton, John R. 1905. Haida Texts and Myths. Skidegate Dialect. Smithsonian Institute. Bureau of American Ethnology. Bulletin 29.

Victoria Gazette. 1859. Bill for Preservation of Game, April 28, p. 4.

Waterman, Thomas. 1973. Indian Notes and monographs. No 59. Notes on the Ethnography of the Indians of Puget Soud. Museum of the American Indian. Heye Foundation.

Victoria Gazette. 1859. Bill for Preservation of Game, April 28, p. 4.

Wilson, Captain. 1866. Report on the Indian Tribes Inhabiting the Country in the Vicinity of the Forty-Nineth Parallel of North Latitude. Transactions of the Ethnological Society of London, Vol. IV, New Series, pp. 275-332. London, 1866.

Wood, James. 1849. Notes on Vancouver Island. The Nautical Magazine and Naval Chronicle for 1849. A Journal of Papers on Subjects Connected with Maritime Affairs, pp. 299-300, London.

Waterman, Thomas. 1973. Indian Notes and monographs. No 59. Notes on the Ethnography of the Indians of Puget Soud. Museum of the American Indian. Heye Foundation.

Whymper, Frederick. 1876. The Countries of the World: Being a Popular Description of the Various Continents, Islands, Rivers, Seas, and Peoples of the Globe, vol. 1, London:Cassel, Petter, & Galpin, 1876.