By Grant Keddie

The shuttle-cock lure and spear, was a unique form of technology used to catch mostly the larger lingcod and rockfish. The fisherman used this device at low tide from anchored canoes or rock points that overlooked kelp beds.

The lure would be pushed down deep with a separate pole that was quickly pulled away from it. The lure then spun toward the surface, the fish darted after it and was speared when it came near the surface. The spear was 4.5 to 6 meters long. It consisted of two or three, unbarbed, fir shafts on the end. The shafts were about 4cm thick, 46cm long and about 10 cm apart at their tips (Swan 1870; Jennes 1934-35; Drucker 1951; Suttles, 1951; Barnett 1955).

The cedar wood lures from the Salish languages family speaking areas all have a round head part carved on a main body. Below the head was the thinnest part that tapered to a thicker bottom. At the bottom was a hollowed-out depression. This portion of the lure was scorched with fire and smoothed. Attached to this main body were two or three paddle shaped vanes, made of maple or other light-coloured wood. These vanes were bound to the body with wild cherry bark which is tough and water resistant.

Figure 1, from Songhees, RBCM 727, is complete with three wooden attached vanes. Figure 2, RBCM 4543, from Sooke, is complete with two attached wooden vanes. Figure 3, (left side) is Songhees, RBCM 9559, and the another (right side), is recorded only as “Coast Salish”, RBCM 13135a. Both are only the main body of the lure with missing the vanes.

Something was Missing?

When I observed these shuttle-cock lures years ago, I was puzzled as to why this device, being made of light to medium weight wood, would not have just floated up sideways. I also wondered how the end of a pole, if pushed into a hole in the bottom of a lure, would be easily pulled out to quickly release the lure.

What was missing was a specific part that was not mentioned in any of the 19th century accounts of it being used and missing from examples in museum collections. That part was a small round stone that fit into the middle of the central bottom of the lure. This stone would have given the lure more centralized weight and balance to spin to the waters surface.

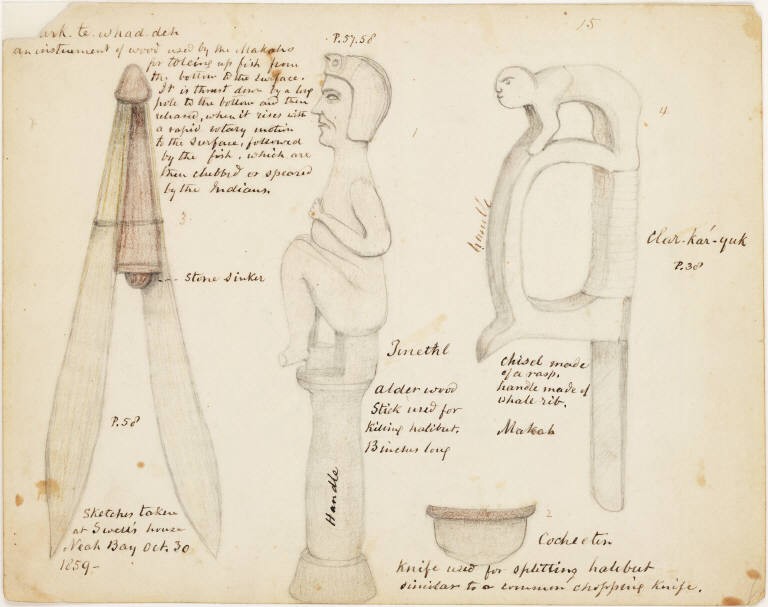

I became aware of this when I observed a round stone in the hole at the bottom of the lure in a drawing made on October 30, 1859 in Neah Bay on the Oympic Peninsula. The drawing shows a stone stuck in the bottom of the lure (Figure 4). Figure 5, shows the cupped hole in the base on the main body of RBCM 4543, where a small stone would have been placed.

Discussion

At least one claim, which in my opinion, is a mis-interpretation, is the suggestion that the lure was pushed down in the water by the same spear that was used to spear the fish. This would not be likely. When two people went fishing, what would work best was when one pushed the lure down while the other was prepared to spear the fish. Yanking a spear with toggles on two prongs would likely detach the toggles and there would also be movement that would alarm the fish. Even a spear with two unbarbed wooden or bone prongs yanked through the water would be distracting to the fish. When I spent many hours as a child with my “red devil” hook and wooden pole fishing from a raft on Skeleton Lake, Alberta, I learned being very quite and not moving was an important factor in catching fish.

Myron Elles wrote briefly about the shuttle-cock lure and spear in the late 1870s to 1880s. His description is confusing as he includes it in sequence with a description of a fish gaff hook and the more common fish spear with toggling points attached to two prongs or fore shafts fitted into a long pole (Elles 1985).

Elles describes the lure: “Another part is made of cedar, as it is light, with two wings of white wood, as dogwood. This, like the last is attached to the pole by thongs, the lower end of the pole also fitting into it. This is first thrust down into the water with the pole. Which is then drawn out, leaving it to rise gradually. The shape is such that when rising it whorls around, and the white wood, shining in the water, attracts the fish, on the same principal as the spoon hook of the whites. When the fish comes within research the Indian spears it with the hook first described” (Elles 1985).

It would appear that those lures with an open, cup shaped bottom in the central body holding a stone, must have been pushed down with a special pole with a cupped shaped bottom that fit over the exposed part of the round stone. This design would also make it easier to pull the pole off of the bottom of the lure.

Elles does not mention the stone, but his suggestion that the lure was: “attached to the pole by thongs”, is in need of further comment. If the latter is true, I might speculate that there is another part of the shuttle-cock lure. There may have been a “thong” attached to the bottom of the pole that lopped around the vanes of the lure pulling them together. We know that U-shaped bend wood hooks were tied when not in use to keep them in a springy state, making them less vulnerable to being broken by the pull of a fish. If this was the case, when the pole was pulled out of the constrained vanes, it would have slipped off the lure vanes, causing them to spring out, initiating an upward movement of the lure.

Shuttle-cock Lures in the Royal B. C. Museum Collection

There appears to be an interesting difference in the four lures shown in figures above that are from cultures within the Salish language family: RBCM 727 is a complete artifact with three vanes, identified as Songhees. RBCM 9559, is also Songhees but is only the main body with missing the vanes. RBCM 4543 is a complete artifact with two vanes, identified as being from Sooke. RBCM 13135a,b,c includes a body with two separated vanes, only identified as “Coast Salish”.

The Museum collection also has four shuttle-cock lures from the Nuu-chan-nulth cultural area on the west coast of Vancouver Island.

These, are what I am calling baton shaped. 10709a and 10709b, from, Uclulet, can be seen in figure 6. These have much smaller vanes than those shown above. Two artifacts, identified from Ohiat, are both complete with two vanes, and are baton shaped. RBCM 2225 (figure 8), has a fish shaped head and has very small vanes compared to RBCM 2224 (figure 7) .

RBCM 4702, from Kyuquot, is baton shaped, but is only the body portion with missing vanes (figure 9).

References

Barnett, Homer Garner. 1955. The Coast Salish of British Columbia. University of Oregon.

Drucker, Philip. 1951. The Northern and Central Nootka tribes. Smithsonian Institution. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 144. Washington.

Elles, Myron. 1986. The Indians of Puget Sound: The Notebooks of Myron Eells. Edited by George Pierre Castle. Whitman College.

Suttles, Wayne. 1951. The economic life of the Coast Salish of Haro and Rosario Straits. Garland Pub. Inc., New York, 1974.e