By Grant Keddie

Indigenous hunting dogs have gone through enormous changes in northern British Columbia and surrounding regions in the 19th and early 20tth centuries. They were subject to large-scale interbreeding and replacement with European dogs.

A focus of attention has often separated out the discussion of northern hunting dogs under varieties called “Tahltan bear dogs” or “Hare bear dogs”. The breeding of Tahltan bear dogs by non-Indigenous owners, and their brief recognition by the Canadian Kennel Club, has given dogs identified by this name prominence in the literature. It is important to know when and from whom information about bear dogs was collected. Here I will present the earliest observations by non-indigenous people, the ethnographic writings acquired from Indigenous people and, where provided, the names of Indigenous consultants who provided information and their perspective on the subject. Are there dogs that specialized in bear hunting or is there a more complex picture that needs to be presented? Were there hunting dogs that hunted everything eatable?

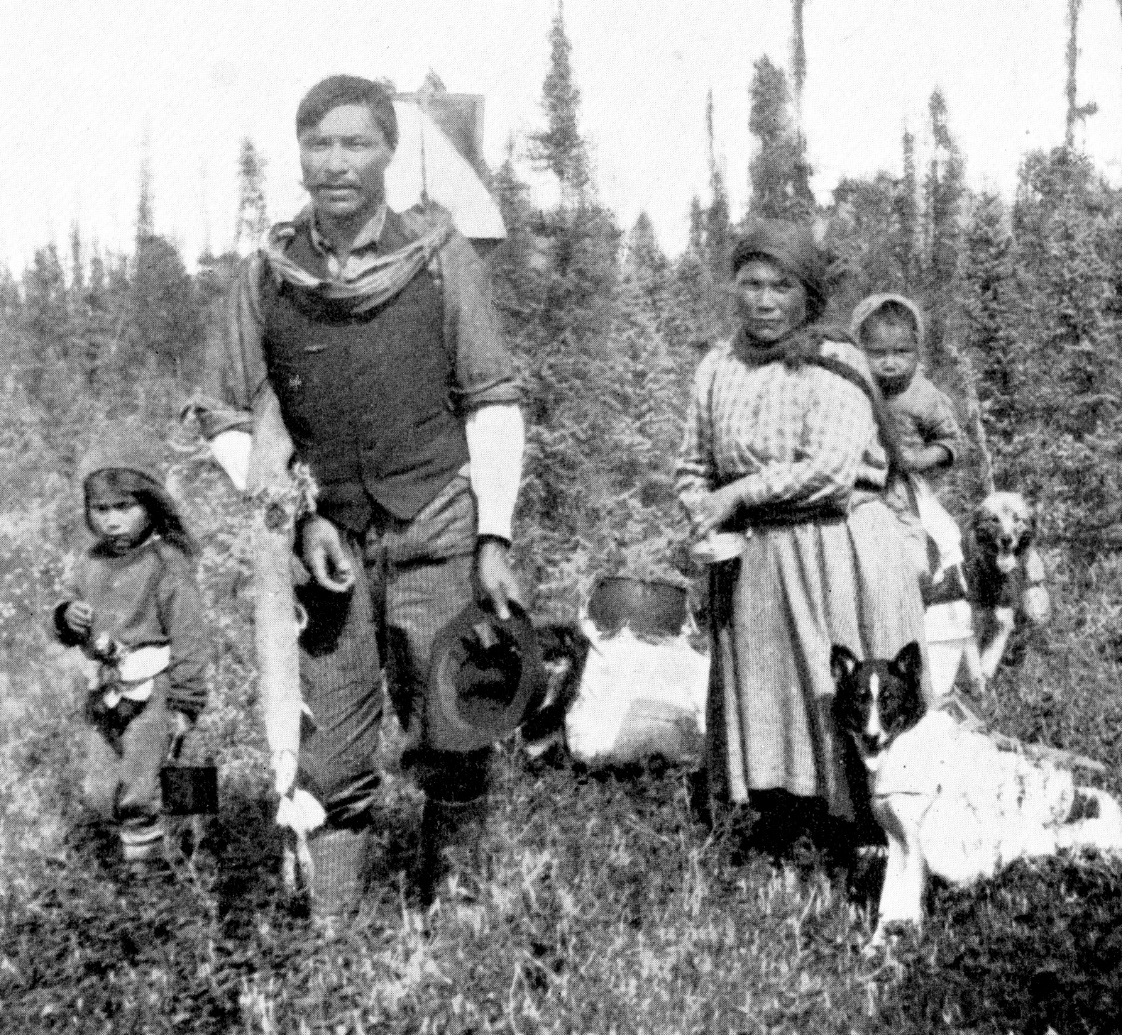

Figure 1, shows an unidentified family of Sahltu Dene on their way to Tullit’a, the old Hudson’s Bay Company, Fort Norman, on the McKenzie River. Their territory extended west from the McKenzie River to the headwaters of the Yukon River.

On the lower right of the photograph is one of the very small, but speedy dogs used in hunting. Here, the dog is strapped into a light dog carrying bag. Most dogs used as pack animals at this time were much bigger dogs, with heavier loads, from highly mixed populations of European dogs, such as labrador retrievers, pointers, collies and Newfoundlands, with huskies and malemutes. Figure 2, shows an example of mixed breed pack dogs used by the Hudson’s Bay Company at Fort Norman, Yukon in the 1920s.

One of the earliest and most comprehensive descriptions of northern hunting dogs, before big changes took place, has been provided by Fur traders, such as Daniel Harmond in 1811-1815, who traded out of Fort St. James, and especially biologist John Richardson, in 1828, who found bear dogs so common among the Indigenous Sahtu (Hare) people in the vicinity of Great Bear Lake. Richardson was a surgeon and naturalist on two Arctic land explorations in 1819 to 1822 and 1825 to 1827, where he made an inventory of plants and animals. Here I will report observations of northern Interior dogs from the earliest to the latest times to show the changes that took place and to help judge the facts of the later commentary regarding the nature of various Interior Indigenous dog breeds.

Figure 3, shows a Sahltu man carrying a pup in a back pack. This was a common practice in the north, In this case, the pups floppy ears indicate this was not fully an older type of the Indigenous hunting dog that has erect ears higher on the head as the small dog in figure 1.

Southeast Alaska. Tlingit Dogs 1790s

Although my focus here is on Interior dogs, I will digress a brief bit to point out some commentary that compares northern coast dogs with others. In 1786, La Perouse observed three to four dogs in every house in Lituya Bay, Alaska:

“They are small; resembling the shepherd’s dog of Buffon (see Keddie 2022; 2023); scarcely ever bark, but make a whistling noise much like that of the jackal” (La Perouse 1799).

In 1791, Etienne Marchand saw the Indigenous dog at Sitka, Alaska as: “of the race of the shepherd’s dog; but his hair is longer and softer. His feet are extremely large; the tail is bushy, the muzzle long and pointed, the ear erect, the eye sharp, the body thick; and his height may be about eighteen inches. He barks little and appears timid with strangers” (Fleurieu 1801).

Over a hundred years later in 1879, the naturalist John Muir was told by Tyeen, a Tlingit man, that in goat hunting: “before the introduction of guns they used to hunt them with spears, chasing them with their wolf-dogs, and thus bring them to bay among the rock, where they were approached and killed”. While heading to Chilcat, on the coast, Muir comments on deer hunting with dogs:

“Deer abounded on all the Islands of considerable size, and alone the shores of the mainland. But few were to be found in the interior on account of wolves that ran them down where they could not readily take refuse in the water. The Indians they said, hunted them on the island with trained dogs which went into the woods, and drove them out, while the hunters lay in wait in canoes at the points where they were likely to take to the water” (Muir 2002).

In 1881, Aurel Krause observed that the Tlingit have: “half-wild dogs that are found in every Indian village, …belong to the race of Eskimo dogs; they have no relationship to the Indian dogs of British Columbia and Puget Sound who could be confused in their appearance with coyotes. They are never used as draft animals, but occasionally taken hunting.” (Krause 1956).

In 1888, Franz Boas, in talking about the Northwest Coast in general says: “The Indians keep a great number of dogs in their villages, which look exactly like the coyote. In the northern villages they are much like the Eskimo dog.” (Boas 1889)

Daniel Harmond’s Observations 1800-1815

In this early period, Daniel Harmon observed dogs in the central Interior of British Columbia and notes the broader changes that were already occurring:

“The Indians have several kinds of dogs. Those which they make use of in hunting, are small, their ears stand erect; and they are remarkable for their fidelity to their masters. They now have a large breed among them. Which were brought into their country from Newfoundland, by the English, when they established themselves on Hudson’s Bay; and from that place they have spread into every part of the country, east of the Rocky Mountain. They are used only as beasts of burthen. In the summer season, they carry loads upon their back; and in the winter when there is snow, they draw them upon sledges.” (Harmon 1957).

Samuel Black 1824

Samuel Black of the Hudson’s Bay Company, traveled with the Sekani of northern British Columbia, on a route from Fort Ware on the Finlay River, west to Lake Thutade, and along the mountains north to the region around the headwaters of the Stikine River.

On June 4, 1824, Black notes the existence of “little” dogs: “The Thecannies … have the art of teaching their small Indian Dogs with erect Ears to hunt alone & the little hairy Beagles will sometimes go a great distance by themselves & tease the animal they fall in with by their constant barking until their master come up”. Black’s later comments indicate that these little dogs were used for hunting different animals. On June 14, 1824 he observed: “saw an animal of white color between two patches of Snow on the Mountains on the left, two of the Indians crossed with their dogs and killed it & proves to be a Mountain Goat”. On July 8, 1824: “where we take our departure a foot for Lake Thucatade, in the Traverse saw two Rendeer driven to the water by the Flys, one of our Thecanies with his little Dogs went after them but returned without success”. On August 14, 1824, Black commented: “the solitude of this Noctural scene is only interrupted by the lonely howl of the Indian Dogs prowling about the mountain sides in anxiety for their masters” (Black 1924).

John Richardson’s Description of 1828

“This variety of Dog is cultivated at present, so far as I know, only by the Hare [Sahltu] Indians, and other tribes that frequent the borders of Great Bear Lake and the banks of the Mackenzie. It is used as a beast of burthen or draught. …The Hare Indian Dog has a mild countenance, with, at times, an expression of demureness. It has a small head, slender muzzle; erect, thickish ears; somewhat oblique eyes; rather slender legs, and a broad hairy foot, with a bushy tail, which it usually carries curled over its right hip.

It is covered with long hair, both on the body and tail, there is thick wool. The hair on the top of the head is long, and on the posterior part of the cheek it is not only long, but being also directed backwards, it gives the animal, when the fur is in prime order, the appearance of having a ruff round the neck. Its face, muzzle, belly and legs, are of a pure white colour, and there is a white central line passing over the crown of the head and the occipital. The anterior surface of the ear is white, the posterior yellowish-gray or fawn-colour. The end of the nose, the eye-lashes, the roof of the mouth, and part of the gums, are black. There is a dark patch over the eye. On the back and sides there are larger patches of dark blackish-gray or lead-colour mixed with fawn-colour and white, not definite in form, but running into each other. …the tail is bushy, white beneath and at the tip. The feet are covered with hair which almost conceals the claws. Some long hairs between the toes project over the soles, but there are naked callous protuberances at the root of the toes and on the soles, even in the winter time, as in all the wolves …Its ears are proportionally nearer each other than those of the Esquimaux dog.

The size of the Hare Indian dog is inferior to that of the prairie wolf, but rather exceeds that of the red American fox. Its resemblance, however, to the former is so great, that, on comparing live specimens, I could detect no marked difference in form, (except the smallness of its cranium,) nor in the fineness of the fur, and arrangement of its spots of colour. The length of the fur on the neck, back part of the cheeks, and top of the head, was the same in both species. It, in fact, bears the same relation to the prairie wolf that the Esquimaux Dog does to the grey wolf.

It is not however, a breed that is cultivated in the districts frequented by the prairie wolf, being now confined to the northern tribes, who have been taught the use of fire-arms within a very few years. Before that weapon was introduced by the fur-traders, a dog, so well calculated by the lightness of its body and the breadth of its paws, for passing over the snow, must have been invaluable for running down game, and it is reasonable to conclude that it was then generally spread amongst the Indian tribes north of the Great lakes.

The Hare [Sahltu] Indian Dog is very playful, has an affectionate disposition, and is soon gained by kindness. It is not, however, very docile, and dislikes confinement of every kind. It is very fond of being caressed, rubs its back against the hand like a cat, and soon makes an acquaintance with a stranger. Like a wild animal, it is very mindful of an injury, nor does it, like a spaniel, crouch under the lash; but if it is conscious of having deserved punishment, it will hover round the tent of its master the whole day, without coming within his reach, even when he calls it. Its howl, when hurt or afraid, is that of the wolf; but when it sees any unusual object, it makes a singular attempt at barking, commencing by a kind of grow, which is not, however, unpleasant, and ending in a prolonged howl. Its voice is very much like that of a prairie wolf. The larger dogs, which we had for draught at Fort Franklin, and which were of the mongrel breed in common use at the fur-posts, used to pursue the Hare Indian Dogs for the purpose of devouring them; but the latter far outstripped them in speed, and easily made their escape” (Richardson 1829).

Tahltan Bear Dog

Bear hunting dogs were once common across northern British Columbia. In historic times the attention of anthropologists and dog lovers was more specifically focused on the Tahltan version of this general dog type.

Descriptions were often made between the northern Interior “bear dogs” and others, often referred to as looking wolf or coyote-like.

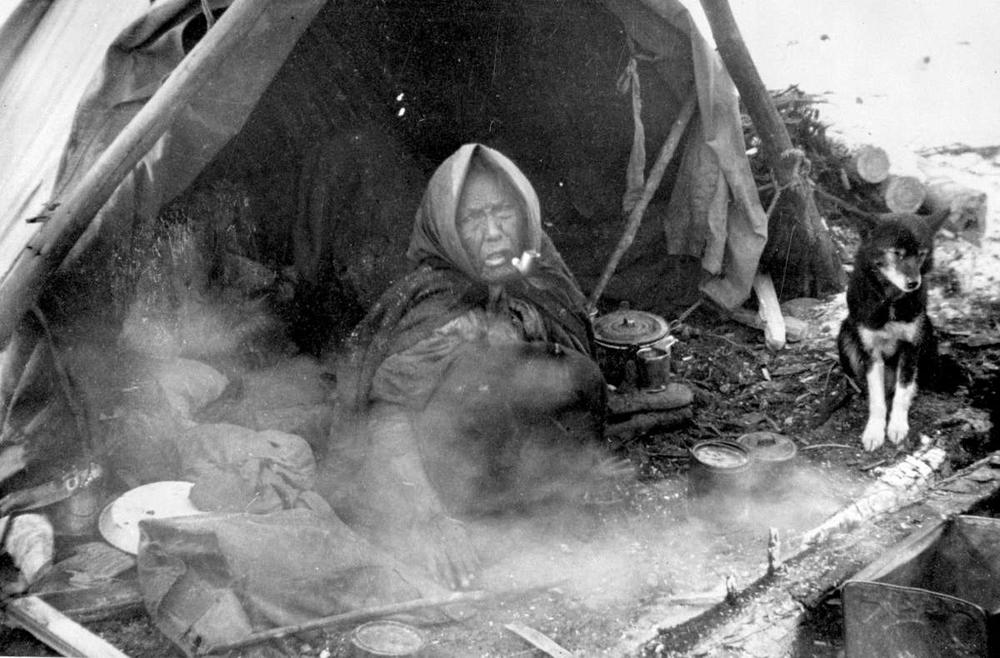

Figure 5, Shows a Tahltan bear dog in 1931. The photograph was labelled: “Tahltan matriarch smoking her pipe, Salmon Creek, Reserve: her little Tahltan bear dog is sitting beside her”.

George Dawson 1876

George Dawson, worked for the Geological survey of Canada, but was also an observer and writer about indigenous cultures. On June 20, 1876, in travelling in Northern British Columbia from Blackwater Crossing to a camp near Indian House, Elikut Lake, north of Anahim Lake, Dawson commented: “the dogs in possession of the Indians rather peculiar, nearly pure white, with rather long but coarse hair, & prick ears, foxlike expression, but rather larger than coyotes. Tails bushy & flattened horizontally. Said to be beaver dogs, used in hunting beaver & following them into water”.” (Cole 1989).

John Muir 1879-1880

The famous naturalist John Muir, in August 1879, travelled up the Stikine River to its first northern fork. Here he met some Tahltan using willow traps to catch their winter salmon supply. He does not mention seeing dogs at the camp, but further up river near Caribou Camp he observed non-Indigenous dogs used in the area and discussed the traditional use of indigenous dogs:

“I saw two fine dogs, a Newfoundland and a spaniel. …The Newfoundland he said caught salmon in the ripples, and could be sent back for miles to fetch horses. The fine jet-black curly spaniel helped to carry the dishes from the table to the kitchen, went for water when ordered, took the pail and set it down at the stream-side, but could not be taught to dip it full. But their principal work was hauling camp-supplies on sleds up the river in winter. These two were said to be able to haul a thousand pounds when the ice was in fairly good condition. They are fed on dried fish and oatmeal boiled together” (Muir 2002).

On the long ridge near the head of Defot Creek, where large numbers of caribou were found, a man named LeClare told Muir: “the Indians, hereabouts, he said, hunted them with dogs, mostly in the fall and winter. On my return trip I met several of these Indians on the march, going north to hunt. Some of the men and women were carrying puppies on top of their heavy loads of dried salmon, while the grown dogs had saddle-bags filled with odds and ends strapped to their backs. Small puppies, unable to carry more than five or six pounds, were thus made useful” (Muir 2002).

Muir, travelled in 1880, with an Indigenous canoe crew from Fort Wrangell, to the glaciers of what is now Glacier Bay National Park, in southeastern Alaska. A small dog came aboard with Rev. Samuel Hall Young of Wrangell. Muir became attached to what he called a “toy dog” that he initially did not want to take on the trip, thinking it would not survive. He soon became aware of the dog’s qualities of endurance and abilities which he describes in detail (Muir 1909). This dog, named “Stickeen”, appears to be an example of one of the smallest of hunting dogs. Although there were images of dogs in various published versions of the Stickeen story, there does not appear to be an original photograph of Stickeen.

Samuel Hall Young, who was on the trip with Muir, later wrote about Stickeen:

“I have told Muir that in his book he did not do justice to my puppy’s beauty. …His markings were very much like those of an American Shepherd dog — black, white and tan; although he was not half the size of one; but his hair was so silky and so long, his tail so heavily fringed and beautifully curved, his eyes so deep and expressive and his shape so perfect in its graceful contours, that I have never seen another dog quite like him; otherwise, Muir’s description of him is perfect.

When Stickeen was only a round, ball of silky fur as big as one’s fist, he was given as a wedding present to my bride, two years before this voyage. I carried him in my overcoat pocket to and from the steamer as we sailed from Sitka to Wrangell. Soon after we arrived a solemn delegation of Stickeen Indians came to call on the bride; but as soon as they saw the puppy, they were solemn no longer. His gravely humorous antics were irresistible. It was Moses who named him Stickeen after their tribe — an exceptional honor. Thereafter the whole tribe adopted and protected him, and woe to the Indian dog which molested him. Once when I was passing the house of this same Lot Tyeen, one of his large hunting dogs dashed out at Stickeen and began to worry him. Lot rescued the little fellow, delivered him to me and walked into his house. Soon he came out with his gun, and before I knew what he was about he had shot the offending Indian dog — a valuable hunting animal” (Hall 1915).

Adrian Morice 1883-84

The Reverand, Adrian Morice worked among and wrote extensively about the Indigenous people of the Interior of British Columbia. In 1883-84 he observed among the Chilcotin:

“There was then in the whole tribe but one dog which was not an aboriginal half-wild animal. The others were uniformly small, grey, wolf-like dogs, with pointed ears and all of the same colour. The exception was highly prized, in fact, known far and wide under the name of Nitâ-lli, ‘white dog’ (Morice 1930:27).

George Emmons 1888

George Emmons was a U.S. Navy Lieutenant with an interest in photography and collecting Indigenous artifacts. He produced many field notes on the Tlingit that were edited and published by Frederica Annis Lopez de Leo de Laguna, an ethnologist and Archaeologist, who also worked in Southwest Alaska and the Yukon in the 1930s and again in the 1950s. She added in some of her own knowledge gained among the Northern Tlingit, which I am including here with Emmon’s information.

About 1888, Emmons observed:

“a tradition with the Tlingit that their dog came directly from the wolf. The Wolf was the crest of one of the phratries, but that did not prevent its being killed, although its flesh was not eaten and its pelt not greatly valued” (Emmons 1991).

De Laguna noted that the Tlingit called the dog “Katle” and recognized the coyote as a “dog of the interior”. Much of the time the animals “had to scavenge for themselves, and the Tlingit did not hesitate to abandon them when they deserted a village for the summer fish camp, or to throw them overboard if they were preparing their canoes for swift attack. …The origin of the dog is attributed to the wolf. Native tradition goes back to the taking of a wolf’s nest in the interior and the training of the young to hunt. From this beginning was developed the dog. …The wolfish strain in the dog is seen in its form and actions, but in time the breed has become smaller and is every color from white to black, through browns and grays.

In character, the dog is rather cowardly, but obedient and long-suffering. It is keen of scent and is used in hunting bear, deer, goat, and land otter. Puppies and even older dogs may be seen with a bear claw or tooth, a land otter foot, or a deer dew hoof secured about the neck to make them good hunters. To give the dog a keen scent, the nostrils of a young dog may be slit with a bear bone, and the blood from the nose caught on a bear’s paw or mixed with bear hair. A bear’s tooth may be rubbed off on a stone and the powder put in water, and this poured down the nose of the dog. …Besides hunting, the dog was used for packing, particularly by the Chilkat who made long trips inland. Dogs lived out-of-doors, often burrowing under the house, and were fed principally on fish, but also hunted on their own account” (Emmons 1991).

De Laguna refers to the Tahltan bear dogs as “small, quick, terrier-like animals, quite different from the larger wolflike dogs used for ordinary hunting and carrying packs. These small dogs, with quick, fearless nips and yapping, could immobilize a bear, dodging his ferocious bites and cuffs, and holding him at bay until the hunter could arrive and kill him. These animals were highly prized, and perhaps limited to the Tlingit who were in close contact with the Athabaskans” (Emmons 1991).

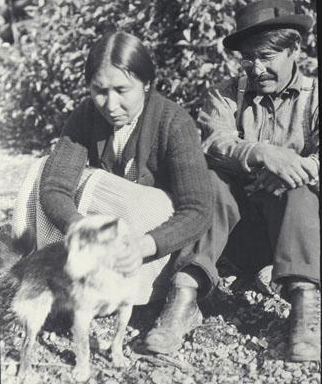

Figure 6A, shows two Tahltan “Bear dogs” with unnamed people.

Figure 6B, shows Mary Jackson (c.1873-Nov.2, 1942), Tahltan, of Telegraph Creek holding a bear dog. On the right is Tahltan Charlie Quash (c. 1880 – Nov. 28, 1942).

The Reed Dog. 1904

In 1904, the Victoria Daily Colonist newspaper records what may be the first Tahltan bear dog taken out of Tahltan territory: “Remarkable Dog. C.P. Reed, of Telegraph Creek, who was a passenger from the north on the steamer Amur, which arrived early yesterday morning, brought down with him a dog which enjoys the unique distinction of being perhaps the first specimen of this breed which has come out of the northern district. In appearance the dog is jet black and much resembles a collie in build. Mr. Reed obtained the animal from a tribe of Indians, who were very reluctant to part with it. It is known in the north as the ‘Bear dog,’ and is noted for its marvelously keen scent. It is said that the bear dreads this particular specimen of a canine than any of its foes.” (Colonist 1904).

James Teit’s Observations. 1912-1915

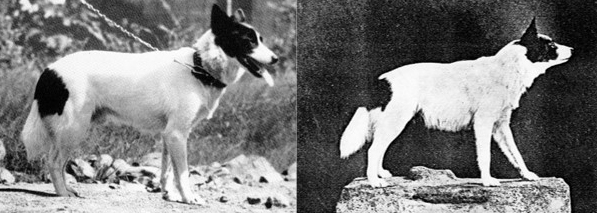

James Teit married into the Spences Bridge Nation in the southern Interior of British Columbia. He was a strong defender of Indigenous rights and wrote extensively about Interior cultures in co-operation with anthropologist Franz Boas (see Wickwire 2019). He travelled as a hunting guide to the territories of several Nations to the north. Teit, provides the best detail on Tahltan dogs, and specifically including the Tahltan bear dogs, in his “Field Notes of the Tahltan and Kaska Indians: 1912-1915” (Teit 1915). Figure 7, is a photograph of a Tahltan bear dog provided by Teit that has been claimed to be that of a “pure breed”. But Teit gives a different impression from his own commentary.

Teit provides a good summary of the context and the Indigenous people from whom he collected his information:

“Most of the information from the Kaska I obtained at the foot of Dease Lake, my chief informants being Albert Dease and his wife. The Tahltan information was collected for the most part at Telegraph Creek from Dandy Jim, who was specifically selected by the tribe to give me the desired information, partly because of his superior knowledge of English and partly because he was considered to be of superior intelligence and one of the best posted persons in the tribe. However, I obtained some information from several other individuals of both sexes of the Tahltan and neighboring tribes, particularly from Big Jackson, Slim Jim, Denis Hyland, Bear Lake Billy, Ned Teit, etc,” (Teit 1915). The last person mentioned was a young Tahltan, who took on the name Teit after James Teit trained him to be a hunting guide. Albert Dease was the Kaska Chief and his wife’s name was Nettie.

Teit’s text on Tahltan and other northern dogs is as follows:

“The tribes claim to have had dogs from the earliest of times and their origin is lost in antiquity. It is thought that they originated from wolves (vis., the timber wolf of the North) and have been tamed by Indians. Probably from the first litter of pups captured by the Indians and raised in captivity. The most, gentle of these were preserved for breeding and in process of time through selection and constant contact with man the Indian dog evolved. The Kaskas especially often bred dogs with male wolfs and do so yet to improve the strain. Attempts to breed them with the fox have always failed.

The Tahltans considered all their dogs to be of one breed or descent, although they varied considerably in size and colour. All had the same shape of face, nose, ears, and tail and the same quality of hair, in these respects resembling wolves. In size they are the large kind, the largest of them somewhat smaller that the timber wolf, and a small variety, the smallest of them no larger than terriers. A number of the dogs were of medium sizes resulting in, at least in some cases from crossing between the large and small kinds, or the small variety may itself have been evolved through selection and breeding of the smaller of the middle-sized dogs who themselves were probably simply individual variants of the common larger dog.

Some Indians paid attention to the breeding of dogs for certain hunting qualities, for instance two dogs known to be specially, good for beaver, would be mated; thus, certain families or strains of dogs possessed more pronounced qualities than others for the hunting of certain kinds of game. This was hereditary in them and no doubt developed through breeding. Certain dogs, say, that did not belong to a strain peculiarity efficient for beaver hunting through training and frequent use became as good or almost as good as those possessing the strain. On the other hand those that did not belong to this particular strain never became any good at beaver hunting. Dogs were also sometimes bred for size and colour but this was more to fit individual tastes or fancies of men, women and children. Some women and children liked small dogs and dogs of peculiar or pronounced colours. Most dogs, especially the larger ones, resembled wolves in their general colours and markings. Like them they were all more or less white underneath and of different shades of grey, brown and black above. Some were very light grey or almost pure white and others were almost pure black. Some were reddish and some spotted. Most of them, however, were intermediate grey and brown colours.

Although the largest of the Tahltan dogs resembled the wolf in its main characteristics, still there was sufficient difference between them to distinguish them. At the present day the dogs of the tribe are all more or less mongrelized, some of them have the old Indian dog in them but most of them are of breeds introduced by the whites (since 1874) and crosses between these. A very few remain, perhaps now not more than two or three, of a very small variety of native dog generally known as the ‘Tahltan bear dog” because it is said that they were particularly used in hunting of bear.

According to one informant they had a good ‘nose’ for bear, taking the hunter to where it was or, in the event of ‘jumping’ followed it up ‘giving tongue’ and worrying it by snapping at it, thus retarding its progress until the hunter caught up. Being small and very nimble, the dog always managed to evade the bear when he

struck at him or rushed him. This specially, small dog of the Tahltan will probably become extinct. All I have seen of them are black or dark grey, some of them are quite black in color with the exception of white patches on the breast, muzzle and sometimes on the feet and underneath the belly and flanks and a very few grey hairs in the body coat. With extreme age they took on a markedly grey phase all over the body.

Dogs were plentiful among the Tahltan. People who had sluts gave all the pups away they did not wish to keep. Dogs had no price, even the most valuable hunting ones, and they were not bought and sold as some dogs are at present day. Anyone who wanted a dog could always get a pup and sometimes also a large dog for nothing.

Formerly no particular care was taken of dogs. They slept just like wolves and lay inside and outside the camp at any place. No kennels or dog houses were made for them, nor even brush spread for them to lie on. At the present day some people make shelters for dogs they value and spread brush for them to lie on. Generally, dogs ran loose, but when considered necessary they were tied up, as for the instance when people were afraid of their stealing or afraid of their being killed and eaten by wolves. As a rule, people kept food and skins and other valuables dogs might eat of tear out of their reach in trees, and on scaffolds etc. When it was inconvenient to do this they tied up all dogs known to steal.

No special halters or ropes were used for tying dogs such as were among the interior Salish. Any kind of stout line of leather or rawhide was used. To give greater strength some of these were plaited. No bone toggles were used on the lines, which were simply tied. Dogs were fed on meat and fish and ate all kinds of scraps and refuse around the camp. When their owners had an abundance of food they got plenty to eat and when food was scarce they necessarily received very little.

The Tahltan aver that their old breed of dogs could not live at the coast, many times the trading parties took dogs home with them, but in all cases these dogs lived but a short time or became very unhealthy. They developed pulmonary troubles and soon died or became mangy. Whites who have taken away to the different parts of the coast specimens of the small Tahltan ‘bear dog’ say that in all cases these dogs soon became sick and died.

Tahltan claim that formerly dogs were used by them for hunting only, and it is only about fifty years ago since they first commenced to pack and haul with dogs. In fact it seems packing and driving came in about the time of the Cassiar gold rush in 1874, and for this reason, the introduction of these processes is generally credited to the Whites. Some Indians aver that a little packing had been done a few years previous to this time. However, this may be, packing and driving generally came in about this date. Wooden sleds and dog harnesses of the common kinds used by whites in the are those in use, and the methods of driving appear to differ in no ways from those generally prevailing in the north.

In packing dogs, pack-bags are used. Some of those formerly in use were made of leather but at the present day all are made of different kinds of canvas or tent material. In shape they are like saddle-bags used on horses. Most of them are of a single strip of canvas of the proper length and width, the middle of which is intended to rest on the dogs back. The ends are doubled up outwards and sewed to the body so as to form a bag on each side, a sufficient loose end being on each side to stretch over and cover the mouth of the bags. Sometimes one loose end is longer than the other, the shorter one simply covering the mouth of the bad od which it is an extension whilst the other reaches over thee back of the dog and covers both. Sometimes both are of equal length, one loose end being tucked under the other across the back of the dog, either end being available as top cover.

Material to be packed is placed in the bags, it being necessary to have the contents of each about equal in weight. The covers of the bags are fastened down with a lacing of thongs passed through a series of loops of the same material in the upper sides of the bags, the lacing passing from one bag to the other across the lids and the back of the dog. The bags are kept in place by a single slash rope of leather or canvas about ten or twelve feet long which is first passed around the ends of the bags below the sides of the dog and then around the bags underneath the dog and then back over the top to the point of commencement. There are several slightly different methods of fastening the bags.

Dogs pack weights of twenty to fifty pounds according to their size or strength. Families have two or three to six family dogs. The difficulty of feeding them at certain seasons almost alone limits their number. Large active dogs good for both packing and driving and well enough haired to withstand severe cold are in demand and some dogs exchange for as high as $40.00 or even more” (Teit 1912-15).

Researchers and Dog Owners after 1930

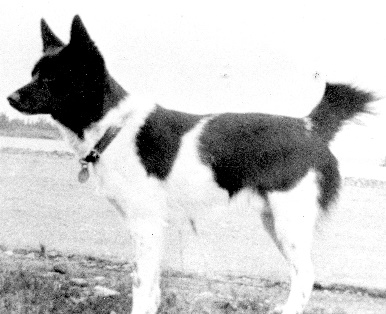

Figure 8, is a photograph, c. 1935, of a Tahltan dog named Chips owned by T. W. S. Parsons.

Diamond Jenness 1933

Diamond Jenness was an ethnologist with the National Museum who worked in many regions across Canada. In 1933, Jenness indicates that Mr. Fenley Hunter of the Cassiar district, reported in 1928, that only “two or three ‘bear dogs’ still survived”. He secured a description of them by J. Frank Callbreath of Telegraph Creek, whose Tahltan dog is seen in figure 9:

“It is a small slender dog about the size of a fox, but perhaps heavier. The head is small with a sharp muzzle, the ears erect and thickish, the eyes very sharp and bright. The tail is bushy and always carried curled over the back, in most cases squarely over the centre of the back, but sometimes curled to one side. While some animals are pure black, the majority have a pure white ring around the neck, and a few white hairs on the feet and sometimes a white patch on the belly; there is no brown or off-coloured hair at all. The animal barks a great deal; its note does not at all resemble a wolf’s but rather the sharp yap-yapping of a fox.

It was found in numbers among the Tahltan Indians about 30 years ago, when the coming of the .44 cal. rifle put it out of business. Previously it was almost unknown for an Indian to get a bear without many shots. There were a few bear dogs among the Bear Lake branch of the Tahltan tribe, a few among the Stick Tarkos in the early days, and a number among the Teslin and Tagish Lake Indians, whence they came originally. There is, of course, no complete history of the bear dog, but I have been told by old Indians years ago that it came from the north, originally from Russia…” (Jenness 1933).

National Museum Specimen

A bear dog was sent to the National Museum of Canada in 1931, by Dr. Leo P. Bott, Jr. and Dr. Glover M. Allen, of Harvard University, obtained a “nearly complete skeleton …with a photograph of it in life”. Bott was a dentist in Little Rock, Arkansas. Allen “procured a live ‘Bear Dog’ from Telegraph Creek on the upper Stikine River. When some one poisoned the animal a few months later, he engaged a local taxidermist to mount the skin and presented it to the National Museum of Canada, where it has now been remounted and placed on exhibition in one of the halls” (Jenness 1933; Canadian Museum 1938).

Figure 10, shows a Mackenzie River region “bear dog” once owned by Dr. Leo P. Bott of Little Rock, Arkansas. The dog was mounted and donated to the National Museum in Ottawa where he was in a glass display case. The case was labelled: “Hunting dog of the Mackenzie River Indians, now almost extinct” (Canadian Museum 1938). A live photograph of the dog was from W. G. Crisp, which was shown in the Beaver Magazine in 1956 (Crisp 1956). The photo of the mounted dog is Canadian Museum of History 77532 and labelled as “Sahtu Dene”.

Jenness goes on to say: “It seems safe to conclude then, that on the Stikine River we still have a few surviving representatives of an aboriginal American dog, probably descended, as Sir John Richardson believed, from the Prairie wolf, Professor Glover M. Allen, of Harvard University, concurs in this opinion. After reading most of the above notes, and examining two photographs of the specimen in the National Museum of Canada, he kindly made the following comments:

‘I think that there can be little doubt that this Bear Dogs represents the same breed as the Hare Indian Dog described by Sir John Richardson so long ago. So far as I know there has been no formal record of the breed in recent years, so that it would be worth-while to put your facts on record. Since writing my paper on the dogs in 1920 (G. M. Allan, Dogs of the American Aborigines, Bull. Mus. Comp. Zool., Vol. 58, No. 9), I have succeeded in obtaining a nearly complete skeleton of one of these dogs, together with a photograph of it in life. I came into possession of the skeleton the spring after the little animal died, and the bones were dug up after the winter was over. My photograph shows a much blacker dog than yours, with the white chest and collar and the rest mostly black. The erect, sharp ears are rather characteristic of native breeds, as well as the fine muzzle and other traits. I have no doubt that these are aboriginal dogs. The skull of our specimen I have compared with that of the small Indian dog of which we have material from ‘pre-basket-maker’ culture [of the American Southwest] and it is very different, less heavy of bone, somewhat smaller in dimensions, but the teeth are the same size. In the Bear Dog, further, the muzzle is much shorter in its bones, resulting in a crowding of the upper pre-molars, throwing them out of line” (Jenness 1933).

William George Crisp

In 1931, Mr. W. G. Crisp (Oct, 3, 1904 -April 4, 1985), the Hudson’s Bay Company’s factor at Dease Lake Post, “obtained a female Tahltan Bear Dog that was pure white with black markings and a short bushy tail that is generally carried erect”. In 1956, Crisp describes that:

“These quick-moving, alert little dogs were common in the Cassiar, when I was at Telegraph Creek in 1931. Generally black and white in colour, sometimes bluish-grey, they ranged in weight from ten to fifteen pounds, the smaller ones with predominantly black coloring being regarded as most typical of the breed. Their glossy coat was clean to touch, long guard hairs thick woolly underfur, and there was a pronounced neck-ruff and long hairs on the flanks. They had the sharp muzzle and prick ears common to other small breeds of native dogs; but a distinctive feature was a straight, short bushy tail, five to ten inches long. Long hairs on the tail gave it the appearance of a giant shaving brush and it was entirely different from the long curled tail shown in an illustration of the Hare dog published in 1829…In fact breeds such as the Pomeranian, Keeshond and Schipperke, to name only a few, with their thick undercoat, prick ears and slender muzzles, all have as many points in common with the Tahltan dog as has the prairie wolf. It seems probable the British Columbia’s Bear Dog is more closely related to commonly known European breeds than to any existing member of the wolf family” (Crisp 1956).

Crisp acquired a female pup in Dease Lake: “Wendy was a pure white with a black face, she was mated with a small black type Bear Dog at Dease Lake and gave birth to four pups. Two of them resembled the mother, one was black and white paws and chest like the father and the fourth was bluish-grey. Two of these pups remained in the country and lived out their normal life span, but two which were sent outside died, apparently from distemper.

…Wendy died of old age in 1939. About that time Commissioner T.W. S. Parsons and Constable J. B. Gray of the B.C. Police were instrumental in having a number of the Tahltan dogs sent outside, where they were recognized by the Canadian Kennel club. A standard of characteristics was drawn up, but as far as I know they have never distinguished themselves in the show ring”. … The only dogs I have been able to trace belonged to a dog fancier in Southern Ontario, who was enthusiastic about the Bear Dogs as pets. But whose activities had been curtailed by ill health. Some pups had been shipped to California …In its native habitat the Bear Dog has by now become mongrelized to the extent that it is unrecognized as a distinct type.

It is curious that they should have survived at all into this century. The area in which they were known to exist – the headwaters of the Stikine and Taku Rivers and the Atlin Lake country – was not exceptionally isolated and had been swept over by two successive gold rushes; in the ‘70s and in 1898.” (Crisp 1956).

The Lower Yukon 1935

In 1935, anthropologists Frederica de Laguna led a party of three other scientists up the Yukon River. Among the Kutchin she observed: “They had many dogs, all of the black, short haired, long-legged English breed”. De Laguna, while later, writing up her field notes added the word “Para”, which referred to the parashoot dogs that were used during World War II. These were often German shepherd-like dogs (de Laguna 2000).

Tahltan, John Carlick

Leslie Clifford Kopas interviewed Tahltan elder John Carlick (Oct, 25, 1897-May 6, 1978) about Tahltan bear dogs. Leslie Kopas (July 9, 1938 – April 19, 2022) was raised in Bella Coola and received a master degree in Anthropology at U.B.C. in 1972. He was the Curator of Archaeology at the Prince Rupert Museum and later a freelance researcher and writer. Kopas quoted Carlick as saying: “They were very smart dogs. They could find a bear’s den through deep snow, chase up grouse and ptarmigan. They could find rabbits, anything. In the old days they kept the Indian alive. If you had a bear dog you could find game. If you didn’t have a bear dog, you starved.” Unlike other working dogs, owners revered the Tahltan dogs, making shelters for them and allowing them to sleep in their tents (Kopas 1982). John Carlick along with Kaska Chief Albert Dease (1877-May 21, 1941) can be seen in a photograph taken on the Dease Lake trail in 1924 (Canadian Museum of History No, 82-10574).

Thomas William Stanner Parsons Dogs

Thomas William Stanner Parsons (Aug 15, 1903- Aug 20, 1986), was a B.C. Police Commissioner who travelled around the northern Interior, interacting with Indigenous peoples. He owned several Tahltan bear dogs.

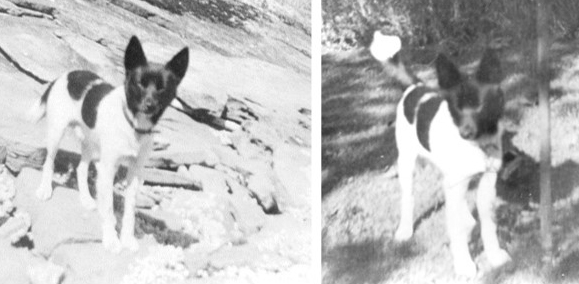

Figures 12 to figure 14 show a series of three photographs of Tipi, one of the Tahltan Bear dogs owned by Parsons. Figure 14, may be an older version of the same dog. Figure 15 is another one of the Parson dogs. Figure 16 is a drawing of a bear dog from the Parsons collection by an unknown artist.

The Kaska Bear Dog

Figure 18, is part of a series of photographs taken by Commissioner Parsons at a Kaska camp at Lower Post on the Liard River south of the British Columbia-Yukon border. No names of the people were provided.

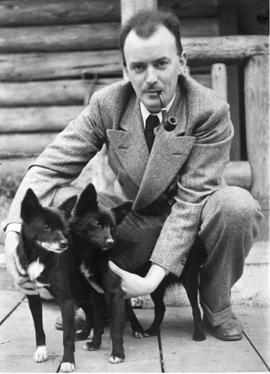

John Blakiston-Gray Dogs

John Blakiston-Gray (Mar 4, 1908 – July 11, 1965), a sergeant with the Provincial Police at Telegraph Creek, purchased 10 dogs from Tahltan people in the period around 1934-1940. In 1944, he was a Constable living in Lytton. In 1949 he worked as a Stationary Engineer at the Coqualeetza Indian Hospital in Sardis. He tried to get the Canadian Kennel Club to recognize the importance of the Tahltan bear dog:

“In the last four years I have combed every Tahltan encampment in the Cassier … I would say that in all this vast territory there were but a mere handful of the true Tahltan dogs in existence. These were procured from the respective natives with the view of establishing the breed …I anticipate and look forward to the day, when I, in turn, can return the dog to its nomadic master, for such is its rightful heritage …” (Bennett 2002).

The Canadian Kennel club recognized the Tahltan bear dog as an Indigenous breed on Feb. 5, 1941. In October 1941, five Tahltan bear dogs were registered by Constable Cray as foundation stock. Only 9 dogs were registered with the Kennel Club.

Figure 19, shows John Blakiston-Gray with two young Tahltan bear dogs about 1940.

“Through his efforts, the Tahltan Bear Dog became a recognized breed, the first dog of native origin to be so in Canada. Harriet Morgon took over the case when Gray retired and turned his dogs over to her. She attempted to breed the dogs in Winsor Ontario … and registered three with the GKC in 1944, and one more in 1948. … Harriet Morgon’s kennel failed and she moved to California. … in 1975, only six Tahltan Bear Dogs were known to exist. Of these, all were male or spayed females, except one. The last remaining bitch, named Nancy Dill, passed away in 1979, without producing any pups. (Bennett 2002). The Canadian Kennel Club removed the breed as a recognized breed in 1979, as it was assumed to be extinct,

Blakiston-Gray wrote a summary of his efforts in “Tahltan Bear Dogs Are Raised Again in the Cassiar”.

“Yes, there still remains a few true specimens of that small, spicy aboriginal commonly known as the Tahltan Bear Dog. Nor, will he go the way of the great auk and the passenger pigeon if it is within my power to prevent it. During the last four years, I have been stationed at the Northern Frontier Post of Telegraph Creek, in British Columbia, Canada. This small post is the hub of that vast territory known to all big game lovers throughout the world as the Cassiar. It has been one of my many duties to patrol this area; not altogether a difficult allotment when properly equipped with adequate bush transport, namely the saddle horse and the dog team. During my many sojourns at the various Tahltan Indian settlements and encampments, I noted that a number of the natives were in possession of a small, alert fox-like dog which, unfailingly, created a great deal of noise when a stranger approached the tent or shack of his nomadic master. The outstanding traits of these little rascals so intrigued me, that I consulted the Rev. W. Pelham Thorman of the Tahltan Anglican Mission. This gentleman possesses a lifetime knowledge upon all ancestral matters relative to the Tahltan Indian. To my amazement. I gleaned from him that this small dog possessed a background parallel to the Tahltan Indian. In other words, he was a native dog, having passed through generations in company with the native. This was all very interesting and I, therefore, resolved to make further inquiries from the natives themselves. I selected the oldest natives in the territory for my informants, namely: Stone-Juice, Hunter Frank and his aged wife, Lame Dick, Broken Jaw Dick, Beale Carlick [Cassiar 1880-Aug. 14, 1960], Charlie Quock, George Etzerza [Tahltan. c. 1866-May 1, 1949] and many others. In some instances, it was necessary to use the medium of an interpreter in my interrogations. Fortunately, I was previously acquainted with the respective Indians, which is a great asset when in conversation with the average native. I must say we had some very interesting chats. The ultimate result of my investigation is such—and there is no doubt whatever in my mind—that this small native dog is the direct progeny of an aboriginal dog, existing in the Tahltan Indian hunting territory of the Cassiar in Northern British Columbia. All the natives that I have repeatedly interviewed over a period of four years agree that their ancestors were in possession of this dog before the encroachment of the white man upon their territory; that the dog was utilized for the purpose of hunting game, particularly bear. According to the older natives the bear dog is a relentless hunter by nose and eye. In days gone by it was the custom of the Tahltan band of Indians to make a semi-annual hunting excursion to the Uplands, Caribou Mountain, Level Mountain, Iskut Country, Nass Country, and many unmentioned locations. Meandering over their vast undulating terrain in the never-ending search for food,

during this period the Indians’ larder consisted of caribou, mountain sheep, mountain goat, bear, groundhog, porcupine, and birds (there were no moose in the country in earlier days) and, upon such occasions, the bear dog predominated in the chase. I am told and, it is interesting to note, the dog was customarily carried in a hide sack on the back of the native hunter and was only released when the quarry or spoor of the quarry was sighted. Possibly the purpose was to preserve the dog’s vitality. The intended game was tormented by circling, nipping and yapping, thus giving the hunter the opportunity of approach to dispatch the animal with arrow or spear. As a rule, two dogs were used in hunting bear. Two or more days before the proposed hunt, the dog was bled. This act, the native considered, gave the dog greater agility and endurance. The dog was stabbed in the hind quarters. The instrument used was the fibula bone of the fox or wolf (there were no coyotes in this territory in the early days). I have no explanation why this particular bone was used for this purpose. No doubt it was an old superstition. A lynx dog—Tahltan Bear Dog—in training during puppyhood, was periodically scratched on the lower nose with the pad of the lynx and was permitted to hunt game in general until it had first treed a lynx. This was graduation, so to speak. I quote for you an extract from a preamble of talk of Charlie Quock, aged chief of the Tahltan Indians, as follows: “Maybe Indian he catch bear dog in snare and keep e’m. That’s what my grandfather he think. We always call him bear dog because he hunt bear. My Uncle Tommy Kooski, he have five bear dogs. I go hunt bear with him Iskut Country when I boy. “Springtime on crust, he best time to hunt. Bear he can’t do nothing, he just got to sit when bear dog get after him. Dog bite him and run back. Bear he get awful mad, he can’t slap dog. Dog he too quick. Easy to hunt bear with dog, you can sneak right up to bear. “To bad bear dog, he nearly all gone now. Dog he no good to us anymore. No one want bear skin any more. Store he won’t buy ’em. We have white man dog for sleigh, and rifle to hunt with. Don’t have to sneak up on game any more. Bear dog he only gets in way. Kids they like for pet. Sleigh dogs they kill ’em first chance they get. “My uncle, he show me way his father train bear dog. When dog puppy, he take him to fresh kill of bear or lynx. He cut pup’s nose and mix blood of bear with pup. He make pup excited by pushing pup against bear. He never forget after that. He think bear cut his nose and it make him mad.” This extract is self-explanatory. You will now understand the reason for the near-extermination of the breed. The dog having no further utility calling, is thrown off by the present native generation as superfluous. I will not go into the general description of the bear dog in this article, as I feel that the photographs should suffice in giving those interested the necessary information on stature. The existing coloring is black, white, grey and slate, whole or in part. I would say that the temperament of the dog is bold, very affectionate to master, independent, and of good temper. The movement is quick and light of foot, fox-like in approach when stalking in play. In fact, the breed has many desirable characteristics and traits that are absent in the ordinary dog. The bark is a fox-like yap, occasionally an apology for a bark. Particularly on moonlight nights, he has a tendency to yapping and yodeling, almost identical to that of a coyote. It is a general belief, which I contradict, that the bear dog will not live in civilization, that is, outside the northern environment. In the past, when the bear dog was more plentiful a number of these dogs were shipped out from the North. Today, I only know of one good specimen over and above those owned by T. W. S. Parsons, Commissioner B.C. Police, Victoria, B.C., and myself. All of these dogs died either from heat prostration or indiscriminate feeding, no doubt the latter. After all, the bear dog’s habitat is the open wilds; he does not respond happily to the pampering and coddling that most of our small canines receive. He is a fastidious eater, preferring small parcels of meat and fish, and is particularly fond of birds. As a rule the bear dog mates but once a year, having one to four in a litter. I have found from experience that it is inadvisable to molest the mother in any way when the offspring are still quite small. Like the fox, they are subject to kill their young. In the last four years, I have combed every Tahltan Indian encampment in the Cassiar from the Stikine to Liard, from Nahlin to Cariboo- Hide. I would say, that, in all this vast territory, there were but a mere handful of true Tahltan Bear Dogs in existence. These were procured from the respective natives with the view of re-establishing the breed, an enterprise of no mean dimension. I anticipate and look forward to the day when I, in turn, can return the dog to his nomadic master, for such is his rightful heritage.

Figure 21, shows a photograph that was copied from the collection of Mason Ball of Telegraph Creek. The back of the original print had written: “Trixie, Tahltan bear dog belonging to Jeff Reese, a customs officer at Stikine boundary”.

Shirley and Tom Connolly Bear Dogs

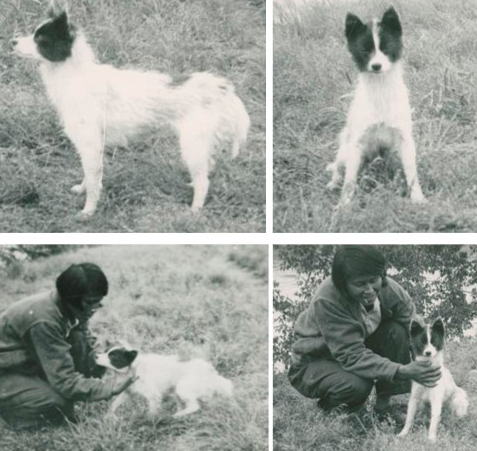

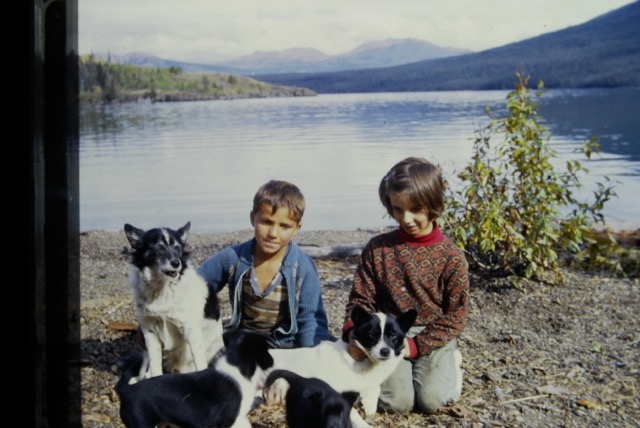

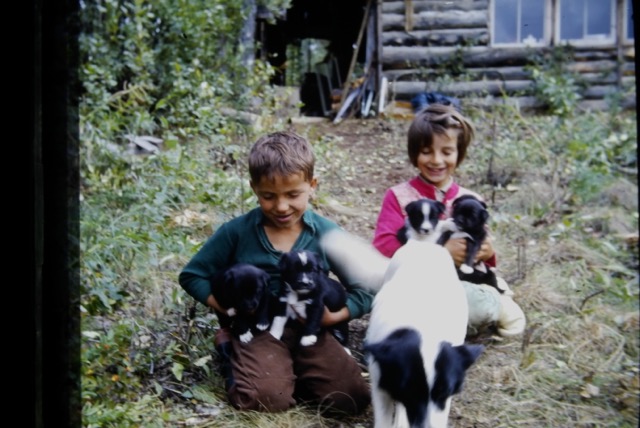

In October 1972, I had the pleasure of observing the alert and keenly observant dogs of Shirley and Tom Connolly (July 4, 1918-July 2, 1975) in Atlin. Tom used bear dogs during hunts for over 30 years around Atlin and Ross River (Figure 25). It has been suggested that Shirley Connolly was the last one to have “pure bred” bear dogs. Figure 22, shows Daniel and Linda Connolly with their bear dogs. Images courtesy of Daniel Connolly.

Figure 22. Daniel and Linda Connolly with their bear dogs. Daniel’s dog was named Sam. Courtesy of Daniel Connolly. c. 1968-69.

Figure 23. Daniel and Linda Connolly with a new bear dog litter.

Figure 24. The Connolly Family camp at Torres Channel on north side of Atlin Lake. Bear Dog “Pork Chop”. 1960s.

Figure 25. Tom Connolly and Joe Ladue of Ross River, caribou hunting in the Yukon with bear dog “Pork Chop”.

Royal B.C. Museum Specimens of Bear Dogs

The RBCM collection includes five crania and mandibles (three female and two male) and three post cranial skeletons (2 female and one male) of Tahltan bear dogs. Some of these were pets whose remains were donated after they died.

RBCM #5027. Cranium and mandible of an adult, Canis familiarsis (bear dog) collected in May, 1944 by T.W.S. Parson. A prepared skin that came with it was (assumed to be moth eaten?) and discarded in 1980. [In the Annual Report for 1944. Page C16. Zoological Accessions: “Constable J. Blakiston Gray, Lytton. Per Commissioner T. W. S. Parson, Victoria. One Tahltan Indian bear dog.”. The older data base had “from an unknown location”. A later addition, now on the database, has the location as “Lake Cowichan”. “Canis familiaris”. The latter addition of the location as Cowichan Lake is likely a mistake. The dog may have been one of Gray’s bear dogs acquired in the north that died and was obtained by Parsons to donate to the Museum.

RBCM # 4669. Cranium and mandibles of an adult male collected in March 1, 1940 by J.W. Shillaker from Chezacut, B.C. Chezacut is near the junction of Chilcotin and Clusko Rivers, N. W. of Alexis Creek, on the Fraser Plateau, S.W. of Quesnel. Annual Report for 1940, page D15. “F. M. Shillaker, Redstone P.O. Chezacut. Fifty mammal specimens”. [A skin from Liard River collected in 1938, cat. no. 004669 ?].

RBCM #5527. Skull, post cranial skeleton and skin of an adult male collected in March 25, 1949, in Victoria. No collector was identified. The skull was partially damaged during preparation. “DNA sample “contaminated”. [“skin, skull & limbs” “C. J. Guiguet [871 collector #]”. Charlie Guiguet was the curator of mammalogy at the (then) Provincial Museum. He had a license to collect animal species for the Museum. This may have been one of Thomas Parson’s bear dogs that he brought back to Victoria from the north.

RBCM #4758. Skull. Post cranial skeleton of an adult female collected in Oct. 31, 1940 by Thomas William Stannard Parsons from Liard River. B.C. (tibia and fibula damaged). Annual report for 1940, page D15. “J. McNaught, Per T. W. S. Parsons. One bear dog”. A mtDNA sample from these remains was analyzed.

RBCM #2892. Skull, post cranial skeleton and skin of an adult male collected Sept. 18, 1938 by RCMP Sgt. McNaught from Liard River, B.C. A mtDNA sample from these remains was analyzed

Modern Studies

Susan Crockford

Susan Crockford began doing studies of precontact Northwest Coast dogs in 1991, making a major contribution to the subject (Crockford 1997; 2000; 2005; Crockford, Susan J. and C.J. Pye 1997; Crockford, Susan. Bernadette Lousier and Colin Moye 2003; Crockford, Susan J. Madonna L. Moss and James F. Baichtal. 2011; McKechnie et. al 2020). On the southern coast of British Columbia and N. W. Washington State she introduced the names: “Village dog” and “Wool dog” based on forensic morphological differences.

In an osteometric and mitochondrial DNA genetic Characterization of the Tahltan Bear dog, Susan et. al. (2003), showed that the RBCM dog remains labelled as Tahltan bear dogs were “the last surviving remnant of a unique aboriginal breed, although it cannot remove doubts about possible crosses with European dogs.”

Part of the objective of the genetic study was to examine the relationship of extinct aboriginal dogs to modern dogs, as well as examining the relationship to wolves. It was shown the “Indigenous Dog” group consisted of “sequences from four of the five extinct indigenous dog samples, including the two Tahltan samples. No modern dogs are found in this group”.

It was concluded that: “The genetic analysis …resolves to some degree the question of aboriginal authenticity of Tahltan Bear dogs. It provides evidence that some of the last surviving members of this breed were indeed, at least in part, true aboriginal dogs. Due to the nature of mtDNA inheritance (passed unchanged from mothers to offspring), 19th or 20th century crosses with male dogs of European ancestry would be undetected by this analysis method. However, even if the Tahltan represents a breed developed during the early historic period, it must have derived its females from aboriginal stock” (Susan et. al. 2003).

Surviving ancient DNA

More recent ancient DNA studies have revealed the existence of unique native American mitochondrial sequences. In Central and South America, researchers found unexpected genetic signatures for herding in the native dogs of the region, like the Xoloitzcuintlels, and the Peruvian hairless dog.

“Many previously undescribed mitochondrial control region sequences in 400 dogs from rural and isolated areas as well as street dogs from across the Americas. However, sequences of native American origin proved to be exceedingly rare, and we estimate that the native population contributed only a minor fraction of the gene pool that constitutes the modern population”. (Castroviejo-Fisher et. al. 2011).

Although all Indigenous dogs in the “New World” came from the “Old World”, there is a need for far more whole genome studies on archaeological dog remains and a larger sample of living dogs to piece together the movement and changes in dogs in North and South America.

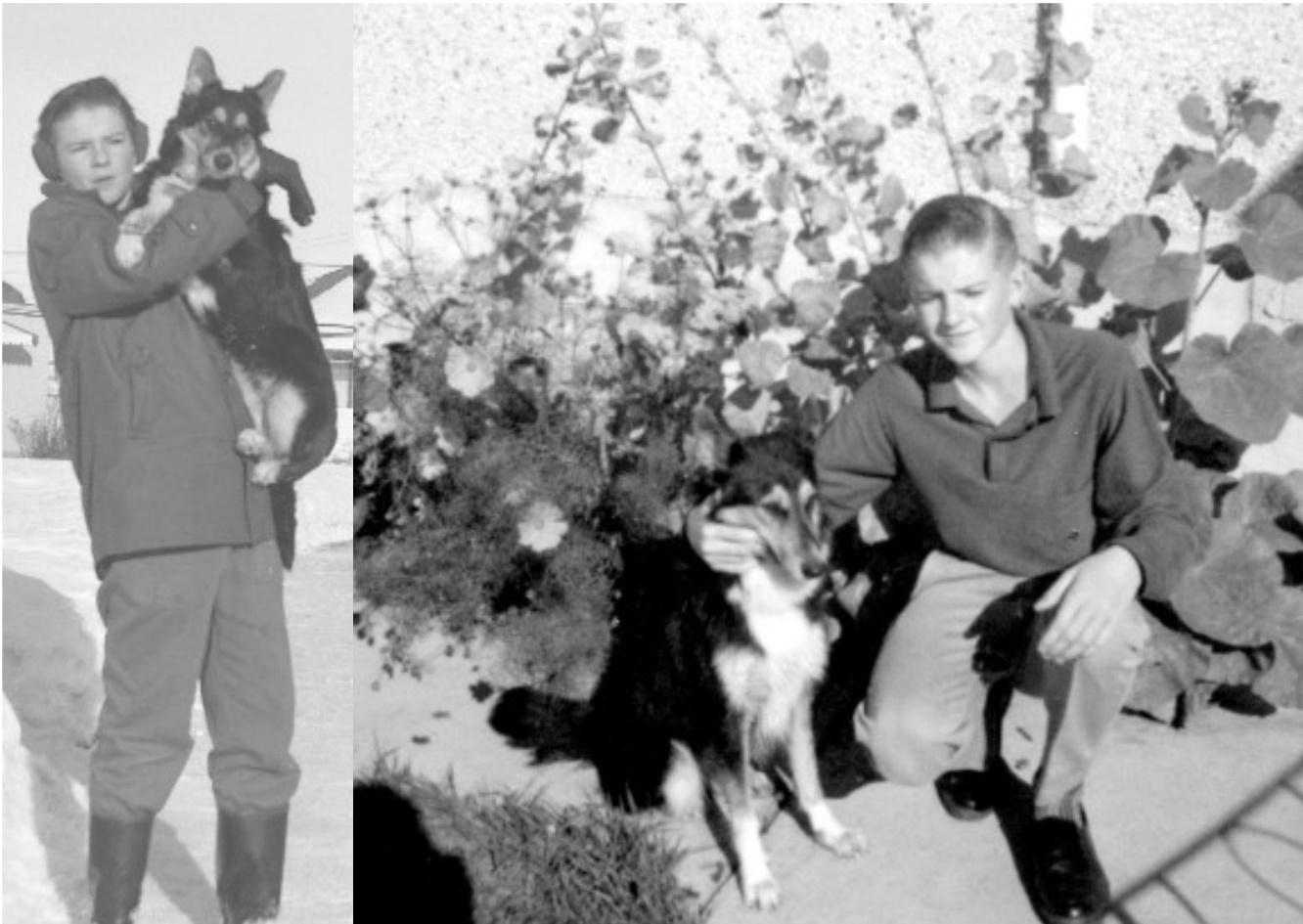

Discussion

When I was a child, I gathered together the free running dogs of my neighborhood, playing with them and observing their behavior. I have had seven dogs of different “breeds” in my life, including a dog from a remote Lake in Alberta, that I know for certain had a Scottish rough-coat Collie mother and a wolf father (Figure 27). As some Indigenous Kaska elders said there was some deliberate inbreeding of larger dogs with wolfs. Figure 27, shows what one crossbreeding example looks like.

The “bear dogs” were general hunters with individuals that specialized at times. The oral history of Indigenous people indicates that they hunted caribou, moose, elk, deer, mountain sheep, mountain goats, rabbits, beaver, porcupine and birds as well as bear. Small hunting dogs could once be found among the Inland Tlingit, Kaska, Sekani, Tagish, Sahltu and others, not just among the Tahltan. The sizes varied but the smaller ones were only 30-40cm high and weighing 4.5 to 8kg.

Figure 28. shows a small Tahltan bear dog with the Nanook Edzerza (1906 – Nov. 12, 1942) martin trapping party, along the Stikine River in 1926. The small bear dog is on the right peeking around a sled, beyond the large sled dogs.

The breeding scenario is best summarized, by Cummings:

“Amongst some Tahltan, breeding of dogs was systemic and methodical with considerable attention paid to selecting certain dogs for their hunting abilities. For example. a dog and bitch particularly adept at hunting lynx might be bred to increase changes of producing pups with these abilities. As a result of this selective breeding, certain strains of dogs were renowned for their abilities in pursuit of certain game. While hereditary seemed to work in terms of producing good dogs, it is also interesting to note that certain dogs not from one of these strains, given sufficient training and exposure, sometimes became as proficient or almost so at their game as those specifically bred for the purpose. However, it must be emphasized that this is not a predicable occurrence. What this suggests is that selective breeding for specific traits resulted in desired qualities at a significant rate, while nurture, i.e., exposure to game and training (and the proper rituals) may, but not with regularity, bring about the same results. The Tahltan knew this. Some people, typically women and children, bred dogs for size (usually smaller than the norm) and colour or shades, but this was to suit individual tastes. In these cases, these traits might be specifically bred for. Women in particular preferred smaller dogs” (Cummins 2013).

Recreating the Bear Dog

Well intentioned individuals who tried to bring back a distinct Tahltan bear dog may have perpetuated its decline by selectively removing dogs that appeared to them as having the right physical characteristics of a specific Indigenous dog.

Murray Lundberg, a Whitehorse based retired motorcoach driver, cruise consultant, writer and amateur historian, reflects on the modern shifting attitudes about the continued attempts to recreate the Tahltan Bear Dog. He wrote the material below in 1998 with a few subsequent additions:

“In 1997, it is not uncommon in the southern Yukon to hear of, or see, dogs which resemble Tahltan Bear Dogs, and several people in Whitehorse and Carcross are attempting to revive the breed. While these dogs may not be recognized as purebreds, more important to the local breed fanciers is the fact that they have both the most important physical attributes of their ancestors, and the intelligence and attitude that has made them so famous” (Lundburg 1998-2020).

Lundberg updated his comments on the Tahltan bear dog in 2007:

“after seeing many of the dogs now being advertised as Tahltan Bear Dogs, I consider it to be a scam. A breed such as the Tahltan Bear Dog cannot be re-created except in the identical conditions in which it was originally developed, and those conditions no longer exist. So a warning to those of you who think that owning a Tahltan Bear Dog would be cool – I share that romantic notion, but the reality is you’ll be paying a great deal of money for a little black mutt”.

Another update was written in April 2020. After his wife saw a photo of a rescued: puppy at Watson Lake, they drove to get the dog and its brother that had been adopted by a Whitehorse family. No one knew what breed it was. Lungberg described it as:

“simply 18 pounds of solid muscle. He had 100 pounds of attitude, though. One of his really distinctive traits was a high-pitched voice when he got excited. I called it his “baby voice,” and expected that he would lose it as he matured. Luckily, he didn’t, and about a year ago, it occurred to me that his ancestors may have been Tahltan Bear Dogs.

Tucker fits the breed description well except for the shaving-brush tail, which I’ve never seen on any of the dogs claiming to be Tahltan Bear Dogs. So, it does seem possible – even likely – that Tahltan Bear Dogs had some very strong genes. That doesn’t change the fact that the breed cannot be re-created, but it has resulted in some wonderfully unique dogs”. (Lundburg 1998-2020).

Conclusion

Indigenous hunting dogs, some with special abilities to hunt specific game, were once common across northwestern Canada. Many varieties of European dogs were in the far north of British Columbia by the mid 1800s, brought by fur traders and after 1857 by the large influx of people during the gold rushes. Dogs were no longer needed for bear hunting as much as before with the introduction of the gun, outbreaks of distemper and the deaths of older dog owners in late 1940s due to epidemics of measles and flu.

As James Teit wrote in 1915, the Tahltan dogs “are all more or less mongrelized, some of them have the old Indian dog in them but most of them are of breeds introduced by the whites (since 1874) and crosses between these. A very few remain, perhaps now not more than two or three, of a very small variety of native dog generally known as the ‘Tahltan bear dog” because it is said that they were particularly used in hunting of bear.” (Teit 1915).

References

Boas, Franz 1889. First General Report on the Indians of British Columbia. British Association for the Advancement of Science. Report on the North-Western Tribes of Canada.

Bennet, Nancy. The Tahltan Bear Dog. The vanished and vanquished fighter of the Cassiars. Dogs in Canada, February 2002.

Black, Samuel. 1824. Black’s Rocky Mountain Journal. 1824. The Publications of the Hudson’s Bay Record Society. London. 1955.

Blakiston-Gray, J. 1943. Tahltan Bear Dogs. Are Raised Again in the Cassiar. Dogs in Canada. 1943:6-7.

Canadian Museum 1938. Mackenzie River Tribes, National Museum of Canada, Guide to the Anthropological Exhibits, Leaflet 3, 1938.

Cole. Douglas. 1989. The Journals of George M. Dawson: British Columbia, 1875-1876. Edited by Douglas Cole and Bradley Lockner. Volume !, 1875-1876. University of British Columbia Press. Vancouver.

Castroviejo-Fisher. Pontus Skoglund; Raul Valadez; Carles Vila & Jennifer A. Leonard. 2011. Vanishing native American dog lineages. RMC Evolutionary Biology. 73(2011).

Colonist, 1904. Remarkable Dog. October 22, page 5.

Crisp, W. G. 1956. Tahltan Bear Dog. The Beaver 287:38-41.

Crockford, Susan. 1997. Osteometry of Makah and Coast Salish Dogs. Publication No. 22, Archaeology Press. Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, B.C.

Crockford, Susan J. and C.J. Pye 1997. Forensic reconstruction of prehistoric dogs from the Northwest Coast of North America. Canadian Journal of Archaeology 21:149-153.

Crockford S.J. 2000a Dog evolution: a role for thyroid hormone physiology in domestication changes. In S. J. Crockford, Ed. Dogs Through Time: An Archaeological Perspective. Oxford: Archaeopress, B.A.R. Intern. S889, pp.11-20.

Crockford, Susan. 2000b. A Commentary on Dog Evolution: Regional Variation, Breed Development and Hydridization with Wolves. In Dogs Through Time: An Archaeological Perspective, edited by Susan J. Crockford, pp. 295-312.

Crockford, Susan J. 2000c. A commentary on Dog Evolution Through Time: An Archaeological Perspective. Oxford: Archaeopress, B.A. R. Inter. S889:295-312.

Crockford, Susan. 2001. Osteometric vs. Genetic Characterization of the Tahltan Bear Dog. Canadian Archaeological Association Conference Paper.

Crockford, S.J. 2002 Animal domestication and heterochronic speciation: the role of thyroid hormone. In N. Minugh-Purvis and K. McNamara, Eds. Human Evolution Through Developmental Change, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 122-153.

Crockford, Susan. 2006. Rhythms of Life: Thyroid Hormone and the Origin of Species. Trafford, Victoria, B.C.

Crockford, Susan. 2010. Thyroid Hormone and Breed Development. Bulletin. Samoyed Club of America, Inc. Vol. 36, No.2. Spring.

Crockford, Susan. Bernadette Lousier and Colin Moyer. 2003. Ostometric vs genetic characterization of the Tahltan Bear Dog. In: K.M. Stewart (eds). Transitions in Zooarchaeology: New Methods and New Results. Canadian Zooarchaeolgy Suppiment #1. Ottawa Museum of Nature. Pages 18-39.

Crockford, S. J. 2004. Animal domestication and vertebrate speciation: a paradigm for the origin of species. Doctoral dissertation, University of Victoria, British Columbia, 2004

Crockford, Susan. 2005a. Breeds of Native Dogs in North America Before the Arrival of European Dogs. Proceedings of the World Small Animal Veterinary Congress, Mexico City. Online at: www.vin.com/proceedings/ Proceedings.plx?CID=WSAVA2005&PID=11071&)=Generic.

Crockford, Susan J. 2005b. Native Dog Types in North America before Arrival of European Dogs. World Small Animal Veterinary Association World Congress Proceedings.

Crockford, Susan J. Madonna L. Moss and James F. Baichtal. 2011. Precontact Dogs from The Prince of Wales Archipelago, Alaska. Alaska Journal of Anthropology. 9(1):49-64

Cummins, Bryan D. 2013. Our Debt to the Dog. How the Domestic Dog Helped Shape Human Societies. Canadian Academic Press. Durham North Carolina.

De Laguna, Frederica. 2000. Travels Among the Dena. Exploring Alaska’s Yukon Valley. A McLellan Book. University of Washington Press. Seattle.

Emmons, George Thorton. 1991. The Tlingit Indians. Edited with additions by Frederica de Laguna, Douglas and McIntyre, Vancouver and American Museum of Natural History, New York.

Fleurieu, Charles Pierre Claret. 1801. A voyage round the world: performed during the years 1790, 1791, and 1792 by Etienne Marchand. T.N. Longman and O. Reese, London. Reprinted by Da Capo Press, 1970.

Harmon, Daniel.1957. Sixteen Years in the Indian County. The Journal of Daniel Williams Harmon 1800-1816. Edited with an Introduction by W. Kaye Lamb. Dominion Archivist. The Macmillan Company of Canada Limited.

Jennes, Diamond. 1933. A Hare Indian Dog. Manuscript on file. Royal B.C. Museum. Ethnology Division.

Lundberg, Murray. 1998. The Tahltan Bear Dog. Everything Husky. The World of Northern Breed Dogs. February 22. (Additional comments on Facebook).

Jennes, Diamond. 1937. A Hare Indian Dog. The Canadian Field-Naturalist. Vol. LI, no. 4:47-50.

Keddie, Grant. 2023. Mistaken Indigenous Wool Dogs. WordPress. https://grantkeddie.com/2023/06/03/indigenous-wool-dogs/

Keddie, Grant. 2022. Dogs of Siberia. Food for Thought on Indigenous dogs of British Columbia. WordPress https://grantkeddie.com/?s=Siberia

Kopas, Leslie Clifford. 1982. Alaska Magazine. June, 1982. Last Days of the Tahltan Bear Dog,

Krause, Aurel. 1956. The Tlingit Indians. Results of Trip to the Northwest Coast of America and the Bering Sea. Translated by Erna Gunther. University of Washington Press, Seattle.

La Perouse, Jean-Francois de Galaup, comte de. 1799. The Voyage of La Perouse round the world in the years 1785, 1786, 1787 and 1788, by the Boussole and Astrolabe, under the command of J. F. G. de la Pérouse.

McKechnie, Iain; Madonna Moss; Susan Crockford. 2020. Domestic dogs and wild canids on the Northwest Coast of North America: Animal husbandry in a region without agriculture. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 60(2020_ 101209:1–14.

Morice, Adrian. 1930. Fifty Years in Western Canada. Being the Abridged Memoirs of Rev. A.G. Morice, O.M.L., Ryerson Press, Toronto.

Muir, John. 1909. Stickeen. Houghton Mifflin, New York.

Muir, John. 2002. Travels in Alaska. Introduction by Edward Hoagland. The Modern Library, New York.

Richardson, John. 1829. Fauna Boreali-Americana, London, 1829:78-80.

Stanwell-Fletcher, John F. 1940. Do Tahltan Bear Dogs Still Live in North America? American Kennel Gazette, April.

Teit, James A. 1912-1915. Field Notes on the Tahltan and Kaska Indians: 1912-15. Anthropologica, No, 3, 1954.

Van Asch, Barbara, Ai-bing Zhang, Mattias C.R. Oskarsson, Comelya F.C. Klutsch, Antonio Amorin and Peter Savolainen. 2013. Pre-Columbian origins of Native American dog breeds, with only limited replacement by European dogs, confirmed by mtDNA analysis The Royal Society. Volume 280, issue 1766.

Wickwire, Wendy. 2019. At the Bridge. James Teit and an Anthropology of Belonging. UBC Press, Vancouver.