August 05, 2024.

Preface

The study of the history of bark shredders and bark beaters is important as they were used in the production of one of the most significant raw materials used by Indigenous peoples on the coast of British Columbia – cedar. As Richard Hebda has shown: “Beginning about 5,000 years ago, closed forests dominated by Douglas-fir and including western red cedar (Thuja plicata) and western hemlock developed in the region as climate cooled and moistened” (Hebda 2024). Richard Hebda and Rolf Mathews (1983) showed the correlation between the “maximums of the cedar pollen curves 2000 to 5000 years ago and the development of massive timber working”. They suggested that “it was only during the latter part of the rise in cedar curves that mature large trees suitable for plank house, canoes and totem poles became available”.

I am interested in examining two types of cedar bark working artifacts, not mentioned in the above, and how they may correlate with the more recent distribution of cedar. Are there unique regional styles of shredders that change through time or correlate with linguistic or specific cultural populations? I have earlier dealt with bark beaters (Keddie 2024).

Introduction

In British Columbia archaeology, artifacts have been mostly viewed as traits seen as part of assemblages that are time separators of regional cultures. Limited attention has been paid to the precise dating of specific artifacts, in different regions, that would allow us to observe their movements. The latter is important to examine local and longer distant interaction speres. When we observe the movement of artifact traits from one region to another, we are witnessing social connections that are part of larger networks, that link people and locations together.

In the future, we need to get more precise radio-carbon dates on organic artifacts (see Brown 2016) and need to be more precise in documenting where the non-organic artifacts are in the sequence. Identifying the relationship of specific artifacts to larger assemblages of artifacts is important if we are to identify the manufacturing and specific social or ritual contexts of which these artifacts may a part. The historic approach, where the ethnographic collection record is examined in relation their counterpart in Archaeological collections, is import where possible. However, the ethnographic record can be complex and many archaeological artifacts have no ethnographic counterpart. Ethnographic collections in Museums also need to be critically reviewed as their recorded context may not be correct. Here I present an overview of both ethnological and archaeological collections of bark shredders from the Royal British Columbia Museum with more added from other museum collections to show the greater diversity and boundaries of shredder types.

The Importance of Cedar

Much has been written about cedar, but before I discuss the use of bark shredders, it is important to re-iterate just how important it is. Anthropologist Philip Drucker best summarized the use of cedar, much from his own observations:

“Another important material, particularly from the Columbia River northward, was the inner bark of the red cedar and, to a slightly lesser degree, that of yellow cedar. Even the northerly Tlingit, in whose territory neither red nor yellow cedar grew, found it necessary to import quantities of the bark, as well as of the lumber, of the two trees. One could very nearly describe the life of the individual Indian in terms of cedar bark: as an infant, he was swaddled in the bark, shredded and haggled to a cottony consistency; his pillow and head-presser were pads of the same material; woven robes and rain capes of shredded bark protected him from rain and cold throughout his life; checker-work mats of red cedar bark were his principal household furnishings, serving as tablecloths a mealtimes, as upholstery for seats, and as mattresses for his bed. With the beginning of European contact, he learned to use sails on his canoe; when he was unable to acquire im- ported canvas, he made sails of heavily woven bark mats; old worn- out mats served to protect his canoe from the checking effects of the sun on bright days. On ceremonial and festive occasions, he wore turbans and arm and leg bands twisted and woven of shredded bark. He stowed his carpentering tools in a basket woven of the same bark. The Nootka whale hunter kept his precious harpoon heads in neatly made pouches of the same material. In historic times, our typical Northwest Coast native found shredded cedar bark to be an ideal gun wadding for the muzzle-loader he acquired from the white trader. And when he died, the chances were that unless he were a chief and entitled to special treatment, his body would be wrapped in a cedar bark mat for burial”. (Drucker 1951).

Bark Shredder Use

Bark shredders are used to make “soft cedar bark” by shredding or chaffing cedar bark for making a variety of items such as string, ropes and all those items mentioned by Drucker. The shredder was not used to cut or chop the bark. Shredders are often mistakenly referred to in ethnographic sources and museum catalogues as choppers, cutters or beaters. Franz Boas gives a description of what he calls “bark breakers”, as provided by Kwagu’l, Johnathon Hunt in the 1890s. Hunt describes how a man takes a small axe and:

“He chops around the bottom of a small cedar tree with black bark. He used the small axe for lifting the bark from the tree at the bottom, and he does the same when he peels cedar-bark . After peeling off the rough outer bark, he also makes a bundle of it and carries it on his back into the house. He puts it down by the side of the fire in his house. Then his wife unties the strings at the ends, and she takes up one of the pieces of bark for making soft bark and unfolds it. She hangs it up back of the fire of the house, and does the same with all the others. Now they are hanging there in order to get dry to get dry quickly, for they are very thick. It takes six days before they get dry” (Boas 1921:126-7).

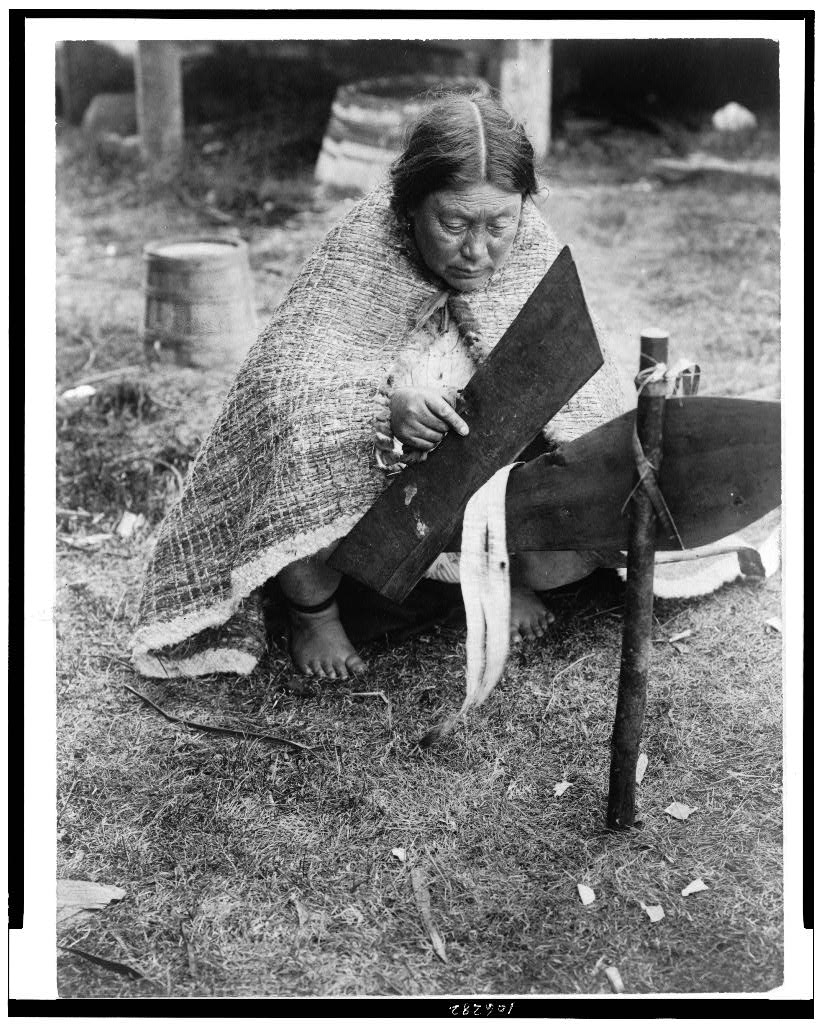

In a different text George Hunt to describes how a woman drives her largest wedge into the floor and attaches, with bark strips, a canoe paddle to it at a sloping angle. The shredder chaffs the cedar bark on the edge of this paddle (Figure 2). A description is also given by George Hunt for how the bark shredder is made:

“The man takes a (bone from the) nasal bone of a whale, and he takes a thin-edged rough sandstone and a small dish, and he pours water into it so that it is half full. Then he puts it down where he is going to work at a cedar-bark breaker. He takes the bone and measures it so that it is two spans and four fingers-widths in length. Then he puts the rough sandstone into the water in the dish, and he saws the bone off so that the end is square He does the same with the other end. When both ends are square, he rubs the edges so that they are straight; and when the edges are straight, he measures the width of one hand for its width, and he measures with a cedar tick to find the center, in this manner. As soon as he finds the center, he marks a line across, and he rubs on each side of the line to make a hole through it, which serves as a grip, he rubs along the lower edge so as to sharpen it. Now he has finished the bark-breaker” (Boas 1921:109).

Bark Shredders in the RBCM Indigenous Collections

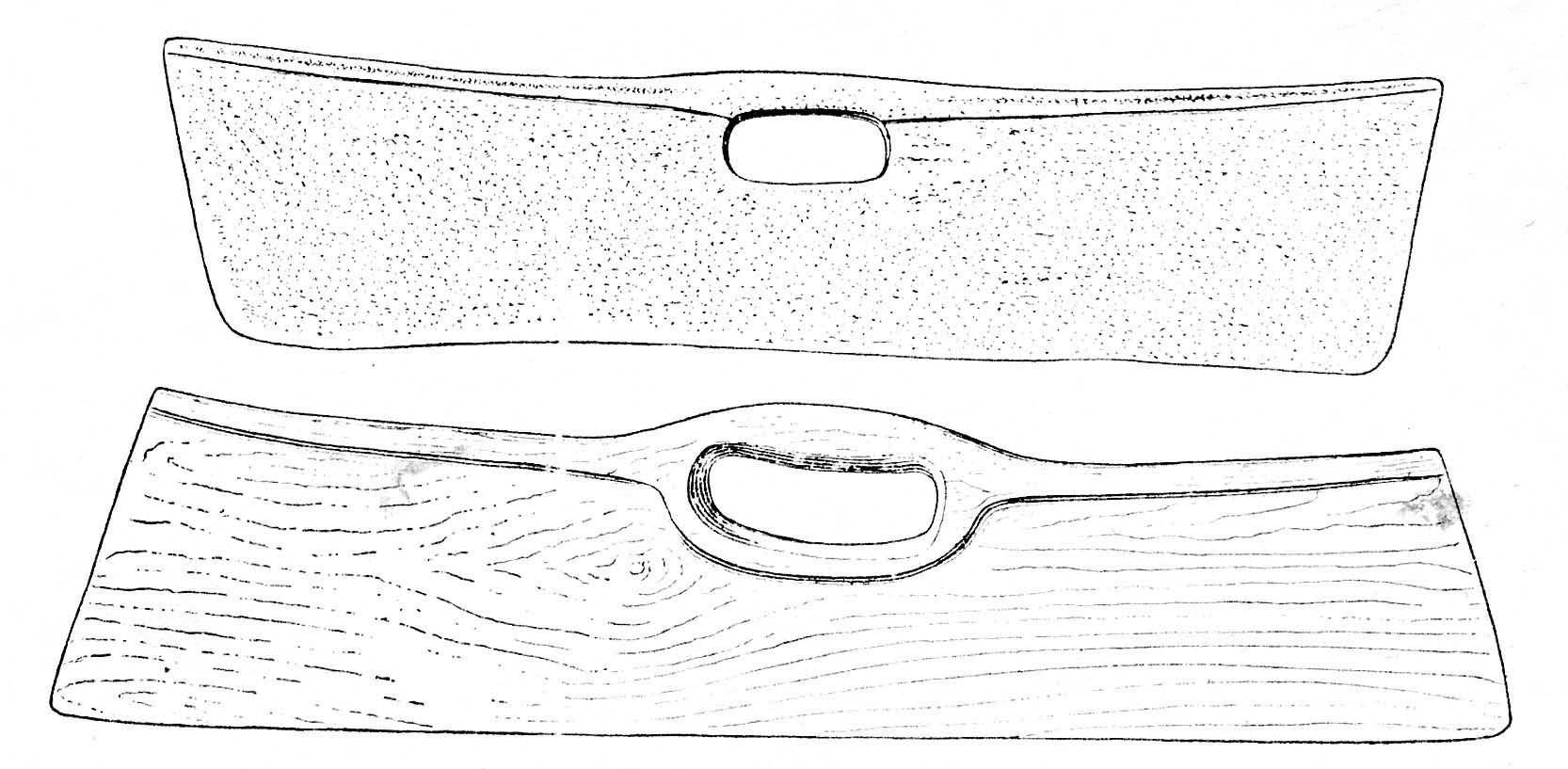

Franz Boas shows a diagram of what he considers as “characteristic Kwakuitl” shredders (figure 4). I will call these long shredders when they are more than twice as long as they are wide. Boas illustrates four other Nuu-chah-nulth shredders and notes: “Those used by the Nootka vary considerable in type”. As can be seen in the following, there are a variety of smaller examples among both populations and longer examples among others. The Boas examples are the majority type based on the collections of several museums.

Nuu-chah-nulth Bark Shredders

There are eleven Nuu-chah-nulth whale bone bark beaters in the RBCM collection. Records identify three as being Moachaht, one as Mowachaht/Muchalaht, one as Ohiaht and three as “possibly” Ahousaht.

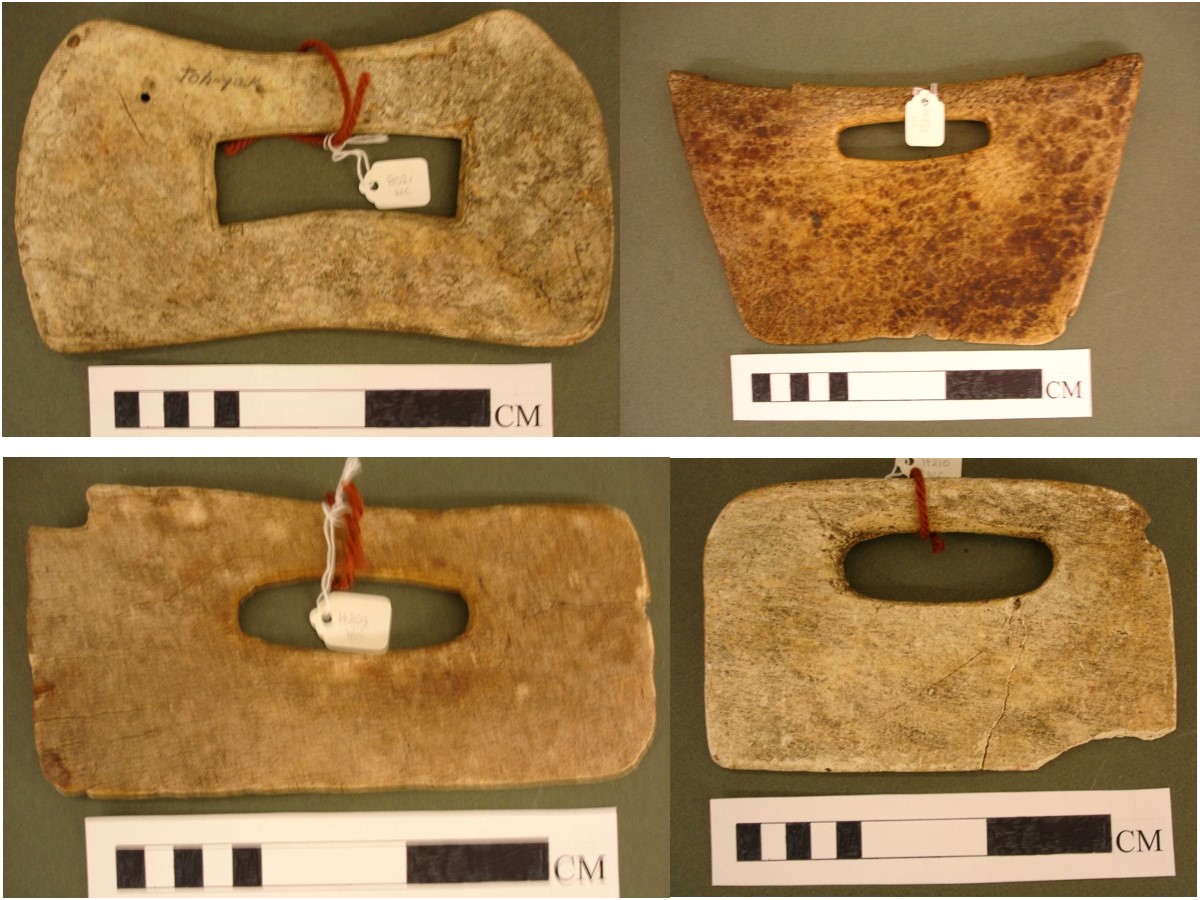

Figure 4, shows an Ohiaht shredder, RBCM 2253 (Dodger’s Cove), in the upper right, with a rectangular central hole. The other three Moachaht shredders, are RBCM 9610, upper left, with carved animal heads on the top of each end, RBCM 9611, lower left with five round cut out holes below the oval handle hole, and RBCM 2254, lower right, with a crudely cut out low central hole and rounded on one side and straight cut on the other.

Figure 5, shows RBCM 8021,in the upper left, with rounded ends and both top and bottom indented. This is recorded as Mowachaht/Muchalaht from Tahsis Inlet. When Charles Newcombe purchased this at Nootka in June. 1912, he records the shredder as being from “Tsã whûn village. On E. side of Tahis Canal”. This would be a Village on Tahsis Reserve #11. Newcombe gives the name of the “bark chopper” as “Toh-yak” (RBCM Archives Add ms. 1077, vol 36, p. 17. R 761, #12).

RBCM 16366, Nuu-chah-nulth, on the upper right, has a longer top than the bottom. It has an elongate oval grip hole that is smaller than most. Once owned by William Locke Paddon (1876-1972) of Watsonville California (as indicated on paper tag), and donated by his wife in 1979. This was one of a group of artifacts he collected when he worked on the Victoria-Alaska Steamship route from 1896-1901.

RBCM 14209, is a rectangular shredder on the lower left and RBCM 14210, on the lower right, is rectangular with rounded top corners. Both are Nuu-chah-nulth, with an uncertain provenience of “Central; Ahousaht?”.

Figure 6, shows Nuu-chah-nulth shredders. RBCM 16365, on the upper left, was collected by the same person who collected RBCM 16366. The former has an incorrect label that reads: “B.C. Indian, Whale blubber chopper. W. L. Paddon, Palm Beach” It has a small elongate hole with a top that is longer than the bottom and has two small raised nubs on an elongate area above the grip hole. The base is slightly indented. Once owned by William Locke Paddon (1876-1972) of Watsonville California and donated by his wife in 1979. This was one of a group of artifacts he collected when he worked on the Victoria-Alaska Steamship route from 1896-1901. On the upper right is a unique artifact, RBCM 14208. Its function is uncertain, but I am including it here as a possible bark shredder. I have not examined the wear patterns on what would be the working edge. It is a Nuu-chah-nulth artifact recorded as “Ahousaht?”, and collected with shredders RBCM 1409 and 14010, that have the same uncertain provenience. RBCM 10778, on the lower left, has a straight bottom and shorter rounded top and RBCM 459 on the lower right, which is longer with raised rounded corners on top with a handle loop that extends above the top.

Nuu-chah-nulth shredders from the National Museum of the American Indian are added in figure 7 to show the greater variety of shapes.

Figure 8, shows a unique example from the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Ethnologisches Museum, with an engraved lightning snake.

Collected in Nootka Sound by Johon Adrian Jacobsen in 1883.(21 x 12 x 1 cm).

Kwakwaka’wakw Bark Shredders

There are 13 bark shredders in the RBCM Indigenous ethnology collection. Three of these are modern creations. Only two are made of wood.

RBCM 16530. (Accession # 1979-3A). Kwakwaka’wakw, Quatsino. Quatsino Sound. Whale bone. Rectangular. Becoming progressively thin towards the lower edge. The elongated grip perforation and a raised portion above the top form the handle. This is one of two shredders purchased from Hazel Wamis. In the ethnology catalogue, Peter Mcnair, the Curator of ethnology, who received the donation and knew the family of the donner, wrote: “Note. Mrs. Wamis (Daughter of the late Charlie Clair of Quatsino) had these in her possession for several years. She says they belonged to her maternal great grandmother (i.e. The late Dick Willie’s mother ?). Claims both used by her great gr, mo.”. Peter McNair observed of this specimen, 16531A: “One specimen looks like an archaeological to me and I suggest should be considered as such” – PLM 30 July, 1979.” This author would agree that the latter is an archaeological example, based on its extensive wear patterns.

RBCM 16531. (Accession # 1979-3B). Kwakwaka’wakw. Quatsino. Quatsino Sound. Whale bone. Rectangular. Becoming progressively thin towards the lower edge. The elongated grip perforation and a raised portion above the top form the handle. The reverse side is more porous and less worn which would be expected based on the way it is used. (see information on 16530. (Accession # 1979-3A).

RBCM 13069. Kwakwaka’wakw. Quatsino. Whale bone

RBCM 18511, “Kwakwaka’wakw?”. Whale bone. This appears to have been a large shredder from which a piece was cut off one end and reground. It has the mistaken information written on it in white ink: “Wooden fish slicer”. This would not cut fish, Oval elongate grip hole at top, that slightly raises above the top. Donated from Sisters of St. Ann. The origin of this seems to be a guess, as it was later noted as being a “Kwakwaka’wakw type”. There is no such known type.

Figure 10, shows both the longer shredders and shorter more rounded examples. Several are mistakenly referred to as a “chopper”. RBCM 2073. (Figure 10, top). Kwakwaka’wakw. Nimpkish. “Alder Wood”. Long rectangular shredder (24” x 5”). Collected at Alert Bay by Charles Newcombe in April, 1913. Referred to then as a “Bark chopper”. On exhibit labelled as “Namgis”. RBCM 10091. (Figure 10, Middle left). Kwakwaka’wakw. ”Yew wood”. RBCM 10092. (Figure 10, Middle right). Kwakwaka’wakw. Whale bone. RBCM 10308. (Figure 10, Lower, left). Kwakwaka’wakw. Whale bone. RBCM 6528. (Figure 10, Lower, middle). Kwakwaka’wakw. Hard Wood ? Evidence of adze marks. RBCM 6529. (Figure 10, Lower, right). Kwakwaka’wakw. Whale bone.

Modern Non-traditional Shredders

Figure 11, shows two examples of long shredders that have painted designs. RBCM 4414. Kwakwaka’wakw. Modern shredder with painted design of a sisutl with human face at centre. RBCM 14937. (acc. # 1975.54). Kwakwaka’wakw. Whale bone. Raised handle with elongate hole. Painted with sea serpent design on one side only. “Painted in glossy black and red and flat pastel green. Gift of Major General G.R. Pearkes and Mrs. Pearkes. Presented to Major General G.R. Pearkes during his tern as Lt. Governor”. L.467mm, W. 12mm, Height 128mm.

Figure 12, include a unique example. RBCM 15622. Kwakwaka’wakw. Nimkish. Model. Wooden. Recorded as “Chopper”. Purchased at Alert Bay from : “Peter Smith Cedar bark chopper made from the blade of a broken paddle”. Peter Smith was from the Klowitsis Band. Born on Turnover Island Sept. 29, 1898.

Added here are the Kwakwaka’wakw shredders from the National Museum of the American Indian to show the greater variety of shapes (Figure 13).

Heiltsuk and Haisla Bark Shredders

There are only three Heiltsuk shredders in the RBCM collections (Figure 15). Some from other museums are added here to that show the same longer type (Figure 14).

Heiltsuk shredders from the Nation Museum of the American Indian are shown in Figure 15. On the left collected by Geroge T. Emmons in 1936. On the right collected by Reverend Thomas Crosby c. 1900 and purchased by George Heye from Crosby in 1908.

Haisla shredders are few, figure 16, shows one from the Nation Museum of the American Indian purchased by in 1905 by George Heyes. It came from a store in Victoria, that sold Indigenous artifacts, called the Lansburg Free Museum. It was not a museum, but a store that one could freely walk around in.

Nuxhalk Bark Shredder

The Canadian Museum of History has one Nuxalk shredder, VII-D-52, dating to 1886 or earlier (Figure 17).

Haida Bark Shredders

A rare example of a Haida shredder (Figure 18) is in the University of British Columbia Museum of Anthropology. Artifact A7067, with abalone eye inlays, came from the collection of William Henry Colinson . The NMAI has two shredders, 1/625, recorded as being Haida (Figure 19). These were formerly in the collection of Frank M. Covert (1858-1929), a New York dealer. They were purchased by George Heye of the Smithsonian from Covert circa 1906.

Tsimshian Bark Shredders

There are no Tsimshian bark shredders in the RBCM Indigenous ethnology collection. One is included here from the NMAI, 4642, collected from Kitkatla in 1905 (Figure 20). This type of shredder was also used for shredding alder bark, which was put in a bath with the cedar to dye it a reddish-brown colour.

Nisga’a Bark Shredders

The NMAI has a one Nisga’a bone shredder, # 6-6278, from the Lower Nass River (Figure 21).

Kuskwogmult Yup’ik Willow Bark Shredder

A rare example of a Yup’ik bark shredder (Figure 22) from Alaska is found in the NMAI, 9-35-12. There are no cedar trees in the region. This artifact would be used for the known practice of shredding willow bark.

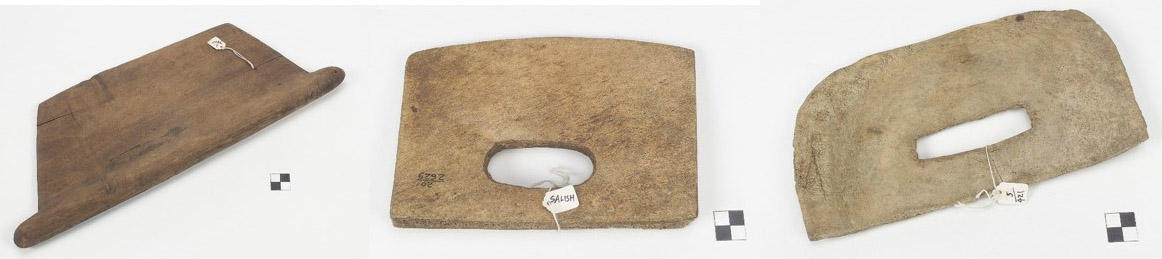

Salish Bark Shredders

There are no bark shredders from any of the Salish Language Family populations in the RBCM Indigenous ethnology collections. They are found, discussed later, in the Indigenous archaeology collection. The Burke Museum # 1-10635, from Saanich is a long rectangular shredder and a Skokomish example, # 34 is just long enough to be a long type with rounded bottom corners and small protrusions on both sides of the top (not shown).

Figure 23, is a shredder from the Smithsonian Anthropology Collection, # 73290. It was collected by the artist George Catlin in 1854, in “Washington territory”. The original label has: “Made of whale’s skull. Handle, a bar between two upright end-pieces, terminating in animal heads. Ornamented by the conventional dot and circle.” Length of blade 9”. The circle- an-dot motif forms the eyes on the top animal figures and there is a row of 7 circle-an-dot motifs with three more extending down from each end of the upper row on the side of the main body. In addition to the larger animal figures on each side of the top of the shredder, there are two small animal heads protruding from the sides below, that have a circle-an -dot motif as eyes, like the upper animals,

Three shredders are from the NMAI (Figure 24). Catalogue # 6/9400, on the left was: “Collected between 1894 and 1907 by Captain Dorr F. Tozier (1843-1926, associated with the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service); Tozier’s collection was purchased in 1909 by the Washington State Art Association (Seattle, Washington); when the Association defaulted on its payments for the collection in 1916, it became the property of the Seattle Land Improvement Company, owned by Fred E. Sander (1854-1921); in 1917, George Louis Berg (1868-1941, director of the Washington State Art Association) negotiated on Fred Sander’s behalf to sell the collection, which was purchased that year by MAI using funds donated by MAI’s Board of Trustees”. This may have been just “attributed to “Salish”. The same collection had material from the west coast of Vancouver Island.

Catalogue NMAI 5/421 (Figure 24, right) is only “attributed” to being “Salish”. The later may have been because the previous owner was a judge, Archer Evans Stringer Martin (1865-1941), who lived in Victoria. Martin did have material collected from a number of locations. Purchased by George Heye from Archer Martin in 1916. Catalogue NMAI 20/2629, (Figure 24, middle) is from an unknown source collected in 1940. It was likely attributed as “coast Salish”.

Quileute Bark Shredders

The U.S. National Museum of the American has three whale bone shredders listed as Quileute. One, (figure 25, upper), was formerly in the collection of Frederick W. Skiff (1868-1947), a Portland, Oregon, accountant and antiquarian. Purchased by MAI from Skiff in 1925. Its former history was unknown. It has been ”attributed” to Quileute. (22.3 x 14.7 x 1.9 cm). Two examples, 5/7584 (figure 25, bottom left), and 6/7586 (figure 25, bottom right), were collected in 1916 by Leo J. Frachtenberg (1883-1930), an anthropologist, who specialized in Native American languages.

Archaeology of Bark Shredders

The longer history of bark shredders is not well documented. Archaeological finds are few, usually fragmentary, and not well dated. Here is an overview of some of the regions where they have been found.

South Eastern Vancouver Island

DcRt-10:1560. Willows Beach. Whale bone. Handle fragment (Figure 26, bottom left). Smoothed natural outer surface on one side and ground porous inner surface. L. (85mm); Height about mid handle 36mm; Thickness about mid handle 8mm. Weight:19.9 gm. Upper zone, 300 to 1200 A.D.

DcRt-15. Cadboro Bay. Recorded as DcRt-Y:14. (old #657) . Whalebone; Rectangular, thickest at top and gradually thinning to working edge (Figure 26, upper left). Max Length 243mm; height 106mm (90mm at concave centre); max. thickness 13mm. No hole. Weight 199 grams. Donated by James Deans. (Newcombe family papers. Charles Newcombe Notes. Feb. 1913. Reel 1760, p. 652.

DcRt-15. NMAI. This was recovered from a private excavation of Godfrey on his property to the east of Gyro Park along the waterfront. His collection was sold to the Smithsonian, Heye Foundation. Associated with late period assemblage (Figure 26, upper right).

DcRu-12:3098. Songhees Reserve, Esquimalt. Whalebone. Fragment of handle. Excavated as part of the joint projects of the Songhees Band and the Provincial Museum from 1974-1977. From layer A with lower time range of around 1300 A.D.

DcRt-8:169. Recovered from Provincial Museum excavations. In data base as “Tool”. Site undated. Most levels are from the late pre-contact period.

DcRt16:1159. (Acc. #2004.22). McNeil Bay. Archaeological Permit Project 2003-232. Thickness 1.44cm; W. 3.74. Two radio-carbon dates of place the bottom of the site around 1450 A.D.

DdRu-5:86. A whale vertebrae epiphysis with a beveled edge was recovered from DdRu-5 (Figure 26, bottom right), North Saanich. Sie dat3e roughly 300-1200 B.P. (Kanipe, et al 2007:116).

DhRx-6:723 &732 & 736. Newcastle Island, Nanaimo region. Handle fragment found in several pieces (Figure ). L. [94mm]; Height at centre of handle 28mm; Thickness at centre of handle 8.5mm. Length of upper hole remnant 59mm.

DeRt-Y:138. [Old # 9176; accession 1959.32). Pender Island. Bedwell Harbour. Max. length 179mm; height 90mm; max. thickness 19mm. Hole length 19mm; height 18mm (round); thickness of handle area above hole 19mm; thickness of handle 17mm. Weight 578 grams. Donated by “Jim Bradley” in 1959.

DefRuv-Y:11 [old # 4391]. North end of Saltspring Island. Length 132mm; height 96mm; max thickness 15mm; Hole length 42mm; height 15mm. Width of handle area about hole 15mm; height from hole to top 21mm. Weight 333 grams.

DgRs-7:15 (a-f). Whalebone (Figure 27). Max. L. 272mm; Max. W. 85mm; width across centre of handgrip hole 78mm; most areas of tool are 7mm thick. I fit together seven pieces that are currently recorded as DgRs-715A-C, DgRs7:16 and DgRs-7:17.

Salish Stone Shredders

DfRw-Y:11. [old 1930-13]. Stone. Max length 151mm; height 112mm; max thickness 14mm. Hole length 36mm; height 19mm; thickness of handle area above hole 11mm. Height from hole to top 18mm. Weight 221 grams. [14D031].

Y-1017 [old #1146 & 10146. Stone bark shredder (Figure 28, upper right). Shist. Max. Length 140mm; height 78mm; max thickness 10mm. Hole l. 16mm; w. 14mm. Height of handle above hole 16mm. Weight 151 grams. The provenience of this is unknow, but is known to have come from the collection of John Humphrey’s of the Chemainus Reserve. Most of Humphrey’s collection came from the south end of Vancouver Island. Humphrey gathered many artifacts from his Indigenous relatives, which he sold to museums.

DeRw-Y:5, [old number 3154]. Slate-like stone (Figure 28, lower right). Rectangular with piece broken from working edge. Max. length 243mm; height 101mm, max. thickness 18mm. Hole l. 33mm; H. 20mm. Height of handle from hole to top 24mm. Thickness at handle 16mm.

Nuu-chah-nulth Archaeological Shredders

DfSi-16. Seshaht village. Ts’ishaa. Whale bone. From the back terrace of the site. The most recent occupation period of the site is dated to ca. 750 to 250 cal. BP) The next oldest is in the 1350–1260 BP range (McMillan and St. Clair 2005).

DfSh-7. Huu7ii village. Huu7ii house 1, had two “bark shredders”. House 1, produced an age range of 1060 to 920 cal BP. This is also thought to just predate the construction of House 1. Twelve results date the house occupation. The earliest, with an age range of 970 to 780 cal BP, comes from the charred wood of a hearth in a shallow pit (F42) at the base of the floor. Two other dates provide similar age ranges (Table 3-1). However, three additional dates from the base of the house floor are more recent and non-overlapping, at around 730 to 550 cal BP. Periodic cleaning of the house floor could result in more recent materials being deposited at the same lower level as those reflecting initial use of the house. The final occupation of House 1 is indicated by three dates taken from at or near the surface of cultural deposits, in one case from a hearth feature (F1) and in another from a concentration of FCR (F19). The three dates are very similar (Table 3-1), with age ranges within 550 to 290 cal BP. These three radiocarbon dates intercept the calibration curve at 460, 490, and 520 BP, indicating that house use may have been during the earlier portion of that age span. Final occupation, therefore, was perhaps sometime just over 400 B.P. “ (McMillan and St Clair 2012).

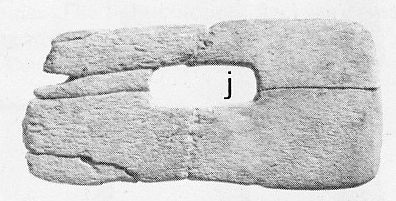

The Yuquot Site. Mowachaht-Muchalaht (Figure 29). Dewhirst found two whale bone shredders that were within a broad time period (Dewhirst 1978, fig. 13j & 1980, fig. 99a&b). CMH IT2F21-2371 and IT2J17A-2765. They were “from the lower levels of Zone IIa, but attributed to the “late middle period”. The Yuquot, Late period, Zone III, is dated to AD 800 – 1790. The Yuquot Zone II, Middle Period is 1000 B.C – A.D. 800 (Dewhirst 1980). Dewhirst describes: “The intact artifacts is nearly is nearly intact in outline with slight concave ends. Both faces are ground smooth. The upper mid-portion of the body contains a rectangular opening 52mm long by 20mm wide. The long side near the opening is ground flat with rounded edges. The opposite side, bevelled on one face to form a sharp edge, is worn down considerably in the middle. The in-tack end of the artifact is beveled on each face to form a narrow edge 2.5mm wide. The artifacts, when intact, measured approximately 1800mm long, 87mm wide and 10mm thick.

The other artifacts misses the upper side and one end. Both faces are ground flat. The nearly intact end has been ground straight and flat, without bevels of any kind of blade. The remaining intact side, not noticeably bevelled, is blade-like and worn. The artifact is 19mm thick. When complete, it was presumably similar to the above described artifact” (Dewhirst 1980).

Four more shredder fragments (no images) include from DfSi-4, a “possible fragment” recovered from DfSi-4 near Ucluelet, B.C. (Dady and Mathews 2003; McMillan and St. Claire 1994); DhSe-2. Shoemaker Bay. Port Alberni. A fragment of a sea mammal bark shredder was recovered from Zone A, component II at DhSe-2. This represents a recent occupation, no older than AD 1000 ((McMillan and St. Claire 1974:108). DfSi-23:808 and DgSl-61:159 from Chesterman beach near Tofino.

Ozette

At the Ozette village site over 90 whalebone bark shredders were found. These are mostly identified as being made from the maxillary bone. None were made from vertebral epiphyses (Fisken 1983; Huelsbeck 1994). Most of the Ozette examples are rectangles, lacking handles or a perforated grip area (McKenzie 1974). These date with the last 400 years.

Northern coast Archaeology Shredders

Prince Rupert Harbour Whalebone Shredder

Bark Shredders are noted for late period sites in the Prince Rupert Harbour region. Most are stone shredders.

GbTo-54 N-01. Ya asqalu’i/Kaien Siding. One highly fragmented whale vertebral disc bark shredder was recovered from GbTo-54. Its stratigraphic position indicates it likely dates to about AD 800. “The 13 fragments were refitted and form an almost complete object; only the top of the handle and a small missing section out of the top right corner are missing. It is a large, elongated D-shaped (self-handled) object with ground rounded edges; the bottom or distal long edge showing considerable use-wear polish. The ventral side has open cancellous bone with some evidence of billowing, suggesting that this may be an infused vertebral epiphysis from a juvenile whale” (Eldridge 2014). .

Prince Rupert Region Stone Shredders

GbTo-Y:65. (old number 1800; accession 1912-1; in red chalk “556”). “Tsimshian”. Quartzite-like material. Flat, metamorphic rock. With semi-circular bottom working area of tool. Animal shaped upper portion with oval hole for hand grip. Weathering on the bottom crushing edge indicates the tool was used even though it appears to be unfinished. There is an animal head at one end and a tail at the other end. A pecked-out area at the bottom of the head may be intended to be a mouth and the raised area above an eye – as a frog-like animal. Max. length 220mm; height 147mm; max. thickness 30mm. Hole L. 60mm; height 20mm. Height above hole to top 34mm. Thickness of handle 31mm. Weight 1315mm. Collected by Charles Newcombe in 1912 ( Figure 30, upper right).

GbTo-Y:66. (accession 1914-1). Nass River. “Tsimshian” . Collected by Charles Newcombe in 1912. (Figure 30, upper right).

GbTo-Y:5. (old number 753; acc. 1889-9, “Fort Simpson”). Stone bark shredder (Figure 30, lower right). Flat, metamorphic rock. With semi-circular bottom working area of tool. Animal shaped upper potion with oval hole for hand grip. Weathering on the bottom crushing edge indicates the tool was used even though it appears to be unfinished. Design includes pecked indentations on both sides at side of handle part and grooved lines curving around from near eye area to eye area on both sides. Andesite. L. 16cm; Height 128mm. Max. thickness 41cm. [old acc. #s 753 and 1889.9; “Ft. Simpson” on tape]. Hole L. 55mm; width 18mm. Height of handle from hole to top 42mm. Thickness of handle 41cm. Weight 1216 grams.

GbTo-31.Ames reported two beaters from GbTo-31,the Boardwalk site, one from Area D AU 2 (general layers dated c. 2000 BC to AD 1000) and AU 3 (AD 1000- AD 1650).

GbTo33. Ames reported two stone shredders from the Lachane site, Area B (2000 BC to AD 1650) and E (3000 BC to AD 1650). (Ames 2005:285-291, 350-351). The wide date range makes it difficult to place these is a specific time sequence (Ames 2005).

GbTo-18. The Dodge Island site. Shist. Head and tail design on side of top of unknown animal. Shown in McDonald 1983, as Fig. 6:29. McDonald dates this shredder (CMH GbTo-18:297) to c. A.D. 1. He discusses stone bark shredders under his 500 B.C. – A.D. 1 section, but in his time sequence diagram, shows zoomorphic bark shredders only going back to 500 A.D.

South East Alaska

Whalebone bark shredders have been found in some late components dating to after 1000 A.D. There is no evidence of them being linked to any specific Alaskan phases of artifact assemblages. None are specifically dated and occur in site deposits that have long time sequences.

Discussion

When documenting the ethnographic record of artifacts in Museum collections, it is important to know the history of how these came to be in the collection. It is important to know the background of the people who collected the artifacts and the knowledge of those people in providing accurate information. How were they first documented and was information added by others, less or more knowledgeable, later. When an artifact has gone through several different private collectors and/or museums, over the years, information on the original provenience may be lost or incorrect information added. Sometimes the provenance of an artifact is “inferred” by a person that may not have a good knowledge of the subject mater.

Many artifacts that were purchased from Indigenous people in the 1870s, and after were acquired by store owners for purposes of profit and not necessarily concern with the facts of their history. Anthropologist Franz Boas wrote about trade when he visited Victoria in 1891:

“Another part of the business which is strange in Victoria are the grocery stores that do very direct trade with the Indians which come to Victoria. …These stores do a particular business by buying Indian artifacts, and you find many Indian wood carvings, weaved items … which they have traded for small goods but sell for high prices to strangers” (Boas 1891).

It is obvious there are archaeological examples of artifacts in ethnological collections based on patterns of weathering. Some of these, even some purchased from Indigenous individuals, were noted as being found eroding out of shellmiddens. It is likely, due to the completeness of some bone artifacts, that they were put in the ethnology collection, rather than the archaeology collections.

Information of the time depth for the indigenous use of the bark shredder in the Northwest Coast cultural area is minimal is a few regions and non-existent in most. Some of the shredders with detailed carving may be a product of early historic influences to produce for the market. Most shredders do not have a specific location provided.

The large D-shaped stone shredders from the northern coast of B.C. are assumed to be bark shredders. There are no early Indigenous ethnographic sources that describe there use for this purpose. When Philip Drucker observed these in the late 1930s, he noted: “These objects, whose use is quite speculative”. Further detailed analysis of these needs to be undertaken to determine what uses they may have had.

Conclusions

Stone bark shredders in the Prince Rupert area may go back to the time period between 500 A.D. and 1 A.D. Their use as bark shredders is still speculative. For those found in excavations, a more thorough analysis needs to be undertaken of their specific placement in the stratigraphy and its dating. Small rectangular stone shredders are found in the southern coast but in small numbers with minimal information on their provenance.

Whalebone bark shredders are found from Quileute territory on the outer coast to the inner Puget Sound in Washington State, and north to the central coast of British Columbia, where cedar trees are most prevalent. On the west coast of Vancouver Island, where whalebone shredders are most prevalent in collections, and in the ethnographic sources, they appear to go back to the time period from around 800A.D. to 1000 A.D.

References

Ames, Kenneth. 2005. The North Coast Prehistory Project Excavations in Prince Rupert Harbour, British Columbia: The Artifacts. British Archaeological Reports: International Series 1342. John and Erica Hedges Ltd, Oxford.

Boas, Franz. 1891. A Visit in Victoria on Vancouver Island. Globus. 59:5:75-77. Worcester, Massachusetts. (From a preliminary draft translation from the German by Klaus Schmidt, for the B.C. Indians Language Project, 2000).

Boas, Franz. 1909. The KwaKiutl of Vancouver Island. Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History. Vol. 8, No. 2.

Boas, Franz. 1921. The Ethnology of the Kwakuitl. 35th Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Smithsonian Institute. 1913-1914. Part 1. Washington Government Printing Office. Pp. 43-794.

Brown, Kelly. 2016. Developing Minimally Impactful Protocols for DNA Analysis of Museum Collection Bone Artifacts. Master of Arts Thesis. Department of Archaeology, Simon Fraser University.

Drucker, Philip. 1943, Archaeological Survey on the Northern Northwest Coast. Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology. Anthropological Papers No. 20. Bulletin 133:17-142.Govenment Printing Office, Washinton D.C.

Drucker, Philip. 1951. The Northern and Central Nootka Tribes, Bulletin 144, Bureau of American Ethnology, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

Dewhirst, John. 1980. The Indigenous Archaeology of Yuquot, a Nootkan Village. In: Yuquot Project Volume 1. The Indigenous Archaeology of Yuquot, a Nootkan Outside Village. Parks Canada, History and Archaeology 39. National Historic Parks and Sites Branch. Environment Canada, Ottawa.

Dewhirst, John. 1978. Nootka Sound: A 4000 Year Perspective. In: Nu-tka. The History and Survival of Nootkan Culture. Sound Heritage 7(2):1-29. Edited by W.J. Langlois. Ministry of the Provincial Secretary and Travel Industry. Victoria, British Columbia.

Elderidge, Morley, Alyssa Parker, Christine Mueller and Susan Crockford. 2014. Archaeological Investigations at Ya asqalu’i/Kaien Siding, Prince Rupert Harbour. Report prepared by Millennia Research Limited. Submitted to: CN Environmental Assessment Lax Kw’alaams First Nation Metlakatla First Nation December 5, 2014

Elles, Myron1 985. The Indians of Puget Sound. The Notebooks of Myron Eells. Edited with an Introduction by George Pierre Castile. Afterword by William W. Elmendorf. University of Washington Press. Seattle.

Fisken, Marian 1994. Modifications of Whale Bones. Appendix D in Ozette Archaeological Project Research Reports, Volume II, Fauna, edited by Stephan R. Samuels, pp. 359–377. Reports of Investigations 66. Department of Anthropology, Washington State University, Pullman, and National Park Service, Seattle

Haeberlin Hermann and Erna Gunther. 1930. The Indians of Puget Sound. The University of Washington Publications in Anthropology. 4(1)1-84. University of Washington Press.

Hebda, Richard J. 2024. Weather and Climate and the Islands of the Salish Sea: Everything in Moderation, with a Few Extremes for Interest. In book: Salish Archipelago: Environment and Society in the Islands Within and Adjacent to the Salish Sea. Pp 17-38.

Hebda, Richard J. and Rolf W. Mathewes. 1984. Holocene History of Cedar and Native Indian Cultures of the North American Pacific Coast. Science. 225:711-723.

Huelsbeck, David R. 1994 The Utilization of Whales at Ozette. In Ozette Archaeological Project Research Reports, Volume II, Fauna, edited by Stephan R. Samuels, pp. 265–303. Reports of Investigations 66. Department of Anthropology, Washington State University, Pullman, and National Park Service, Seattle.

Kaeppler, Adrienne L. 1978. ‘Artificial Curiosities’ Being An Exposition of Native Manufactures Collected on the Three Pacific Voyages of Captain James Cook RN [Exhibition catalogue], Bishop Museum Press, Honolulu.

Keddie, Grant. 2024. Indigenous Bark Beaters in Coastal British Columbia. Grant Keddie Word Press Web Site.

McMillan and St. Clair. 1994. The Toquaht Archaeological Project: Report on the 1994 Field Season. Unpublished Report Submitted to the Toquaht Nation, Ucluelet, and Archaeology Branch, Victoria.

McMillan, Alan D. and Denis C. St. Clair. 2012. Huu7ii: Household Archaeology at a Nuu-chah-nulth Village Site in Barkley Sound. With appendices by: Gay Frederick, Iain McKechnie, Ursula Arndt, Dongya, Ian D. Sumpter Beth Weathers, and Marlow G. Pellatt. Archaeology Press, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby.

McMillan, Alan D. and Deni E. St. Clair. 2005. Ts’ishaa: Archaeology and Ethnology of a Nuu-chah-nulth Origin Site in Barkley Sound. With appendices by Susan Crockford, Gay Frederick, Martin Magne, Iain McKechnie, Ian Sumpter and Michael Wilson. Archaeology Press, Simon Fraser University. Burnaby B.C.

McMillan, Alan and Deni St. Clair. 1994. The Toquaht Archaeological Project: Report on the 1994 Field Season. Unpublished Report Submitted to the Toquaht Nation, Ucluelet, and Archaeology Branch, Victoria.

McDonald, George. 1983. Prehistoric Art of the Northern Northwest Coast. In: Indian Art Traditions of the Northwest Coast, Edited by Roy L. Carlson. Pp. 19-120.Archaeology Press. Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, B.C.

McKenzie, Kathleen H. 1974. Ozette Prehistory: Prelude. Unpublished M.A. thesis, Department of Archaeology, University of Calgary.