Preface

I have always had a love of caribou and was saddened to learn about the extinction of the Dawson caribou (Rangifer tarandus dawsoni) after seeing its physical remains in the (then) Provincial Museum collection. This seemed to have been a preventable extinction. I learned about the importance of caribou and their habitat when doing an archaeological survey of portions of Wells Grey Park in 1970. I met Ralph Ritcey who gave me a copy of his recent paper on the mountain caribou of Well’s Grey (Ritcey 1970). I also met Park supervisor, Charlie Shook (1924-2000). Charlie guided big game hunters to the park in the 1940s, he started as an assistant ranger in the park in 1954, and worked as supervisor until 1971.

Charlie Shook said “one caribou is worth 20 moose”, when it comes to saving their habitat. He thought fire suppression should focus on protecting caribou’s increasingly more limited habitat. In winter, caribou of the park are dependant on five species of lichen of the genus Alectoria (Edwards, et. al. 1960). Moose are capable of expanding into a greater diversity of habitats. They only moved south from the arctic watershed into the Pacific watershed near the Fraser River and Giscome Portage area around 1890 (Fannin 1892).

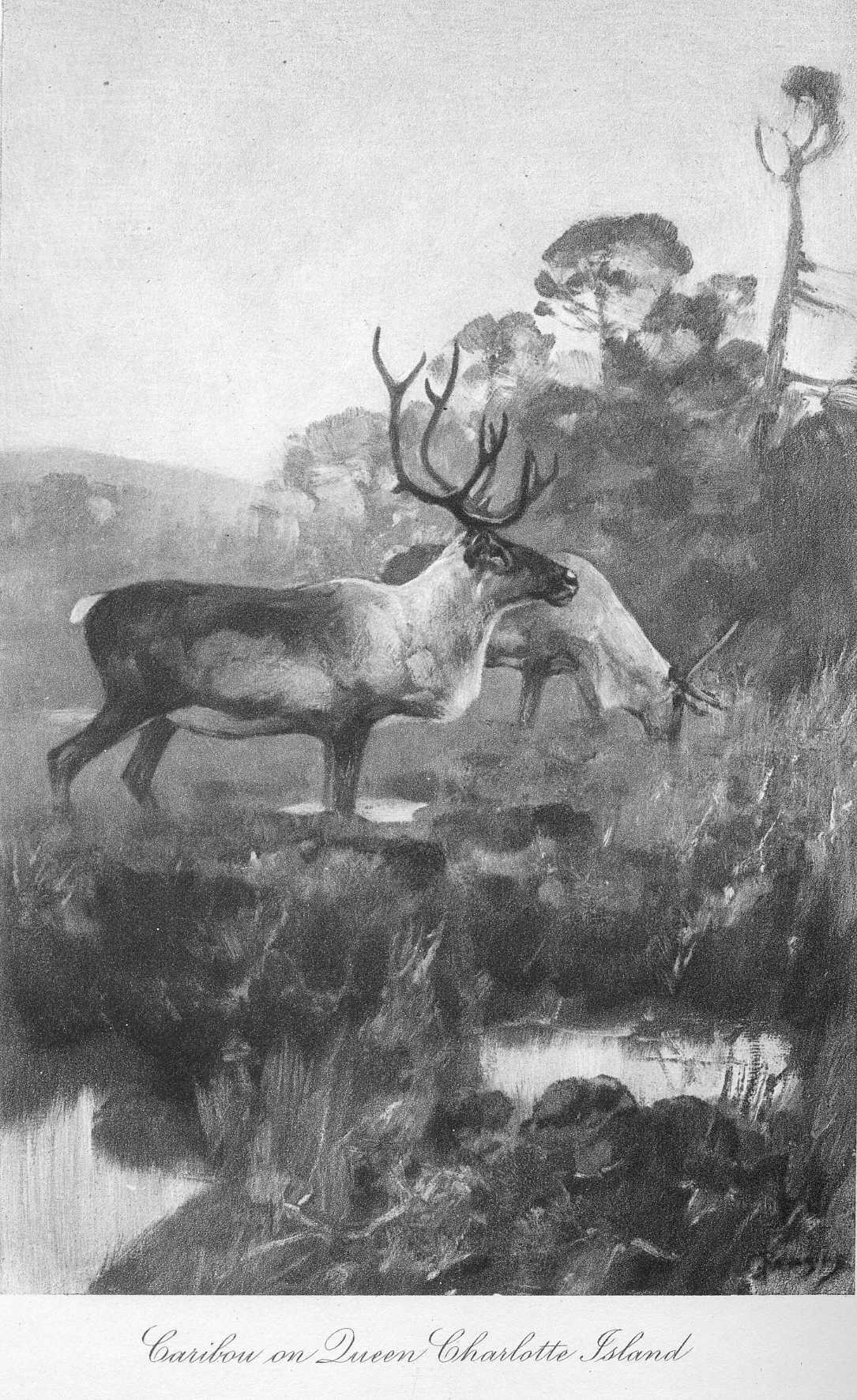

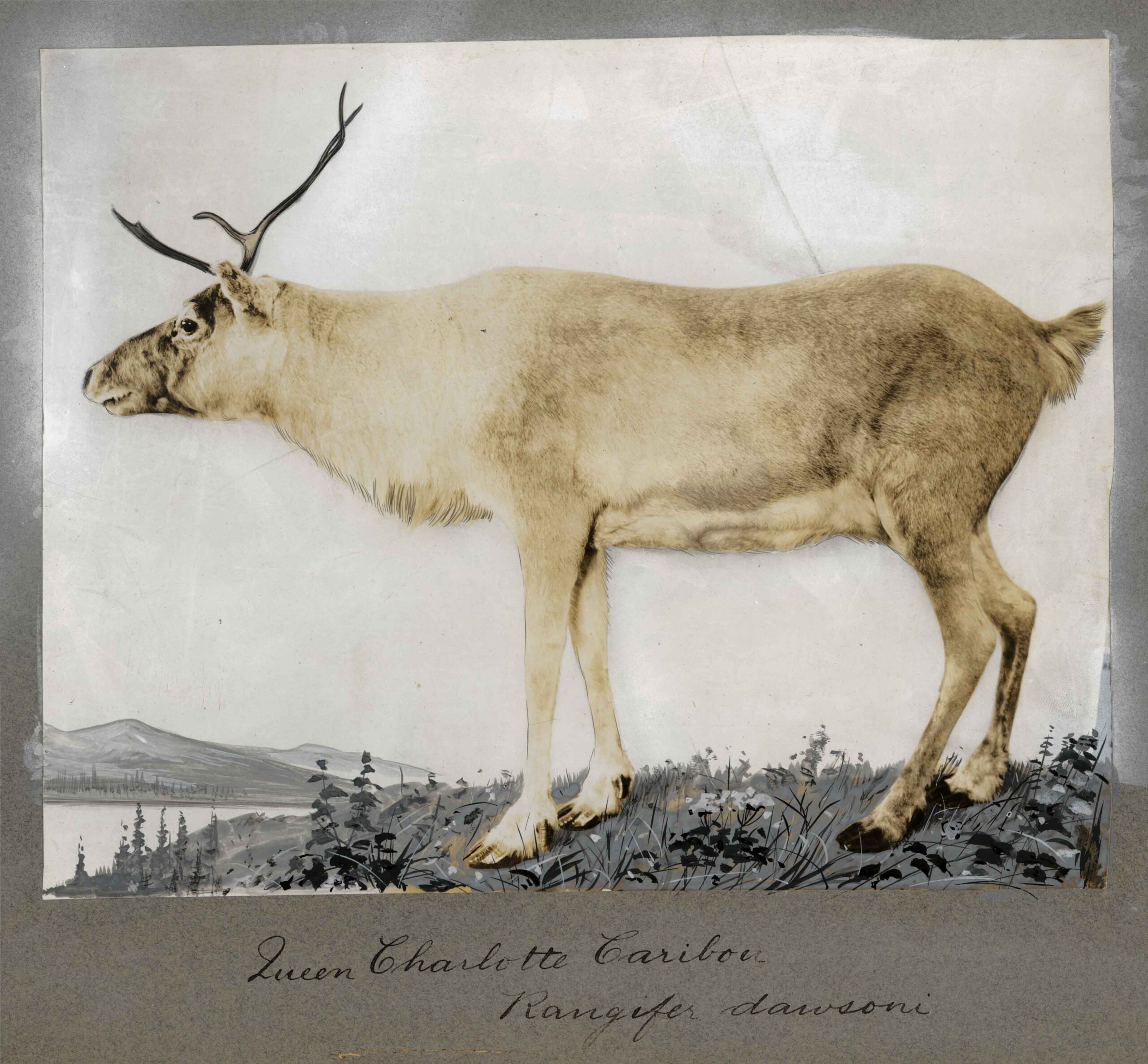

Figure 1, is a Photogravure made from a reconstruction drawing of Dawson caribou by the wildlife artist Carl Rungius (Aug. 18, 1869 – Oct.21, 1959). From Sheldon 1912.

I later learned that biologist, Robert Yorke Edwards. who was my director at the Royal B.C. Museum (1974-1984), when I was a curator of archaeology (1972-2022), had, in 1950, encouraged the undertaking of a ten-year wildlife study in Wells Grey and later oversaw the expansion of the park to include Battle and Green Mountains. In 1954, he published an article on “Fire and the decline of a mountain Caribou herd”, ungulates and snow depth (1956) and others on the caribou with Ritcey (1959; 1960). (See Cannings and Kool 2021).

In reading the ethnographic literature of the southern central Interior, there seemed to be a lack of information on Indigenous use of caribou, as opposed to moose. This is likely because mountain caribou had already been drastically reduced with the gold rush and the introduction of the gun. Indigenous people in the region had mostly become moose hunters by the time they were interviewed by anthropologists or written about by historians. Charlie Shook told me about Ed Fortier of the Chu Chua reserve, who was the last Indigenous person to hunt caribou in the region. I had recorded an archaeological site at a caribou crossing and heard there were old caribou traps in Wells Grey, where caribou were herded into lakes to be speared. I made a special effort to visit Edgar Fortier. He last hunted caribou on Battle Mountain in the 1940s and had seen caribou traps in “Indian valley” when younger, but, at the age of 101, his memory had gone and I missed an important opportunity to learn so much. Edgar was born in Kamloops on February 19, 1869 and died at Chu Chua, December 9, 1971. His mother was an Indigenous woman named Josephine Alexis and his father Charles Fortier was born in France.

In recent years the caribou populations have continued to decline and some herds are on the verge of extinction. This issue has become a significant topic that needs serious action. The main success story today is the caribou recovery efforts in the Peace River region by the Saulteau First Nation and West Moberly First Nations working with the Provincial and Federal Governments. The agreement signed February 21, 2020 includes the commitment to protect over 700,000 hectares of important caribou habitat in northeastern B.C.

Introduction

I wanted to know more about what led up to the extinction of the Dawson caribou. Here I present a historical overview with commentary on the Dawson caribou remains in the Royal B.C. Museum and what we have leaned about them in more recent years.

The Dawson Caribou that lived for thousands of years on Haida Gwaii only became extinct in the early 1900s. In the non-Indigenous world, there was a long period of discussion as to whether they actually existed. This story reflects the ideas about human relationships with the “natural world” as seen in the late 19th and early 20th century, both in terms of native species and the lack of knowledge about the effect of introducing new species. One of the significant questions in the scientific world to this day is whether the Dawson Caribou were a relict population that survived through the last glacial period, or moved later to Haida Gwaii from the mainland.

I will present an overview of the commentary in the beliefs and attitudes of people in various occupations from religious leaders, government and Museum officials, scientists, and explorer-hunters. I will also summarize what has been learned to date from modern archaeology and DNA studies.

Figure 2 is RBCM 1484, the taxidermy mount of portions of three caribou specimens. The main skin of one with bottom leg portions of another and the skull and antler of a third.

Historical time sequence of written observations of Dawson Caribou

1787

James Colnett (c. 1753 – Sept. 1, 1806), observed from Haida Gwaii in August of 1787: “The Quadrupedes must be numerous from the different Skins the natives wear, the only ones I saw were Dogs, a small land Otter, & Deer” (Galois 2004:113). Since there were no deer on Haida Gwaii at this time, the reference to deer may actually pertain to the fur of the Dawson caribou. Although deer skins may have been traded from the mainland – as was known for mountain goat.

1878

George Dawson (Aug. 1, 1849 – Mar. 2, 1901), first pointed out the existence of the caribou on Haida Gwaii when he visited May 27 to October 17, 1878. He noted that the Haida name for caribou is xis-koo (Dawson 1878). Dawson indicated that: “There is pretty good evidence to show that the wapiti occurs on the northern part of Graham Island, but is seldom killed. The small Deer (G. columbianus) is not found on the islands, nor is the Wolf, Grizzly Bear, Mountain Sheep or Mountain Goat”. Dawson later corrected his previous use of the word wapiti in a letter to the naturalist Ernest Seton Thompson:

“At a later date I ascertained that the animal in question was not of the Wapiti but the Caribou, from Mr. Charles, formerly connected with the Hudson’s Bay Co. in Victoria. He had a skin of the animal, imperfect, but with horns and hoofs sufficient to show its general character. “The only published reference 1 have made to the occurrence, that I can remember, is in a paper on the Later Physiographical Geology of the Rocky Mountain Region in Canada. Trans. Royal Society of Canada, Vol. VIII, Section IV, 1890, pp. 313. This is as follows:

“One further circumstance may, in conclusion, be referred to here as being readily and intelligibly explicable on the hypothesis of a considerable elevation of the land at about this time, (close of the glacial period.) This is the existence at the present day of Caribou in the northern part of Queen Charlotte Islands. In a former report on these islands, I have spoken of the occurrence of the Elk or Wapiti on them. This statement was, however, based merely on Indian report, as none of the animals in question were seen. Since that time 1 have learned from Mr. W. Charles, that the animal in question is really the Caribou, and I have been shown by him the skin and antlers of one of these animals. The Caribou is not found anywhere else in the region of the coast, either on the islands or on the- Coast Ranges, though it roams over high plateaux to the east of these ranges. The shortest distance between any point of the Queen Charlotte Islands and the nearest islands of the Coast Archipelago is thirty miles, and the intervening strait is subject to rapid tidal currents. The isolation of the Queen Charlotte Islands is in fact so complete that the Deer, which inhabits all the other islands of the coast, is not found in this group.

The Indians of the Queen Charlotte Islands have evidently long employed the antlers of the native Caribou for the manufacture of various implements, clubs, etc., as some of the oldest of these in our collections are of that material, which was evidently prized. These Indians are not great bunters and in fact dislike going into the interior of this island and on the higher ground where the small bands of Caribou occur’.

You will notice from my remarks above quoted that these animals must in ail probability have been a long time entirely separated from any others, and I should think it highly probable with an animal so variable as the Caribou that they may have developed considerable peculiarities.” (Thompson 1900).

Figure 3, is a Haida Gwaii caribou antler club used in warfare, from the Canadian Museum of History.

1880-82. The Type Specimen. RBCM 1483.

Alexander Mackenzie, was a trader for the Hudson’s Bay Company at Massett starting in 1869. In 1880 he:

“sent a fragment of the skull of a caribou with part of the horn attached, averring that the animal had been killed in Virago Sound by an Indian. …This imperfect specimen, having passed through several hands, was finally lodged in the Provincial Museum at Victoria. … In 1900, Ernest Seton Thompson [Aug.14, 1860 – Oct. 23, 1946] described it as that of a new species which he named Rangifer dawsoni. In view of the uncertainty attached to the origin of the specimen and also its fragmentary character, other naturalists were unwilling to accept it as the basis for a new species.” (Sheldon 1912).

The above specimen is the same as one of those referred to by ethnologist Johan Jacobsen (1853-1947), after his visit to Massett in the fall of 1881. Jacobsen was purchasing a pole from a “lesser chief by the name of Stilta, who also went by the name of Captain Jim”. He later wrote: “Captain Jim is a very intelligent young man who in the summer of 1881, was the guide of the old miners mentioned above [Mr. Stirling and Mr. McGregor at Gold River oil establishment] and during their roaming in the Interior of the Island he found that caribou were there. He shot several of them and I later saw their skins and antlers in Victoria” (Jacobsen 1977). Captain Jim’s name is given as Joshua Stilta on his son Harold Edward Stilta’s birth certificate of Sept. 6, 1899.

In 1882, The Daily Colonist editor, after conversations with J. D. Robertson and James Deans (June 17, 1827 – July 17, 1902), who came down from Haida Gwaii the day before, reported: “Two or three years ago several deer and rabbits were turned out on the Queen Charlotte Islands near Masset harbour by the missionaries. They have done well and are multiplying rapidly. Formerly there were neither deer, rabbis, snakes, panthers nor wolves on the Queen Charlotte group.” No mention is made about the caribou remains sent by Mackenzie.

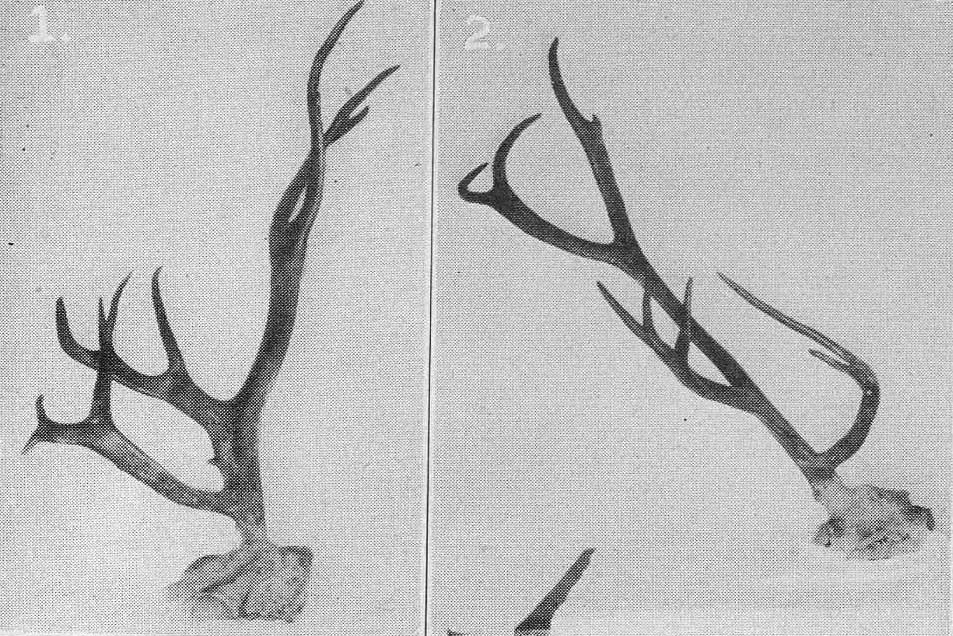

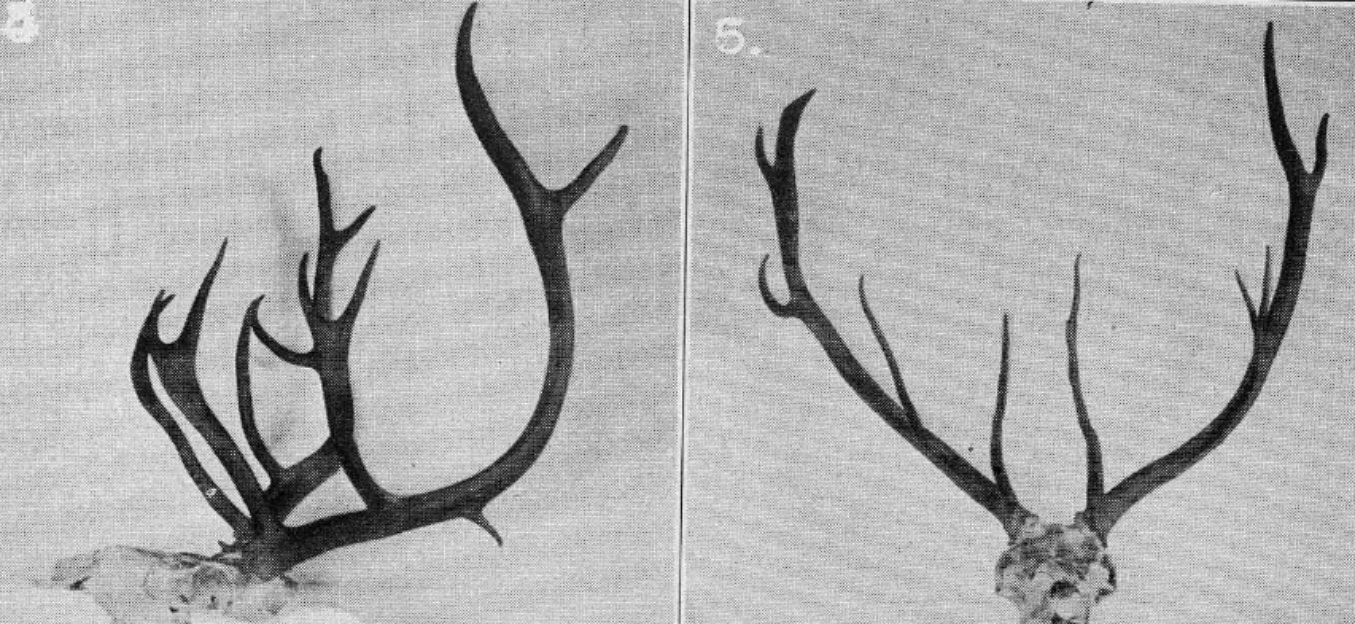

Figure 4, shows the side and front views of the RBCM 1483, type specimen of the Dawson caribou as presented in Sheldon’s 1912 publication. The photographed were taken by biologist C. Hart Merriam during his research.

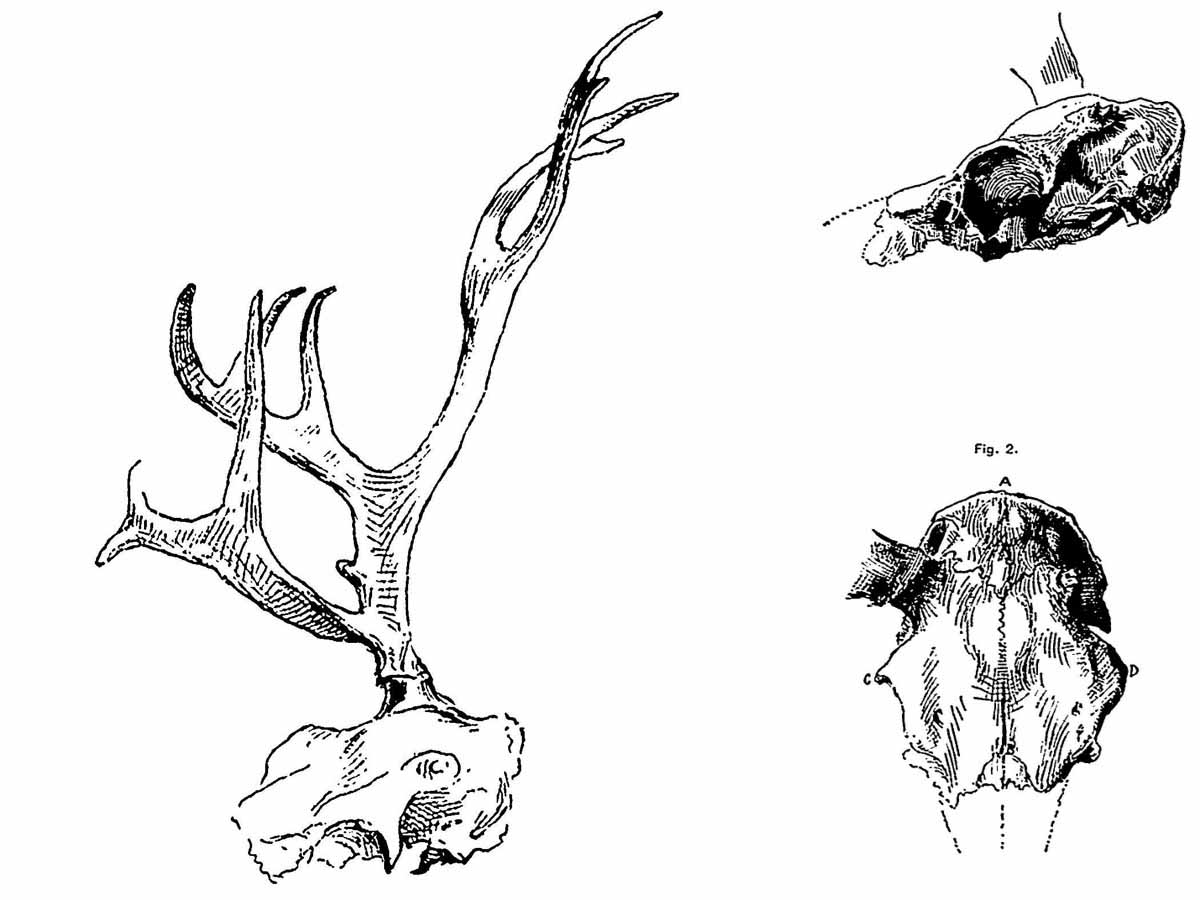

Figure 5, shows the type specimen as drawn by Alexander W. F. Banfield March 12, 1918 – March 8, 1996), much later in 1936.

1884 – 1886

Newton H. Chittenden (1840-1925) turned in an Official Report of the Exploration of the Queen Charlotte Islands for the Government of British Columbia in 1885. He had written four interim reports in 1884. In it he noted: “The Indians report having seen a species of caribou on the northwest part of Graham Island”. He also reported that “Deer and rabbit have been placed upon Graham Island by Alexander McKenzie Esq. of Massett, and the latter by Rev. Mr. Robinson upon Bare Island in Skidegate Inlet” (Chittenden 1886).

In 1886, William A. Robertson sent a short version of the report titled Report of Exploration of Queen Charlotte Islands, to William Smithe, Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works, dated December 7, 1885. He reported: “Caribou Deer. There is said to be a large species of deer, supposed to be the caribou, lately found in the mountains south and west of Virago Inlet. There are also a few deer that have been placed there by Mr. A. McKenzie, of the H.B. Co.’s post at Masset, and if a few more were added, as well as a few goats, they would rapidly increase, especially in that section of country. A colony of rabbits was also liberated by the same gentleman, and are now very numerous. His next project, I believe, is the raising of beavers.” (Robertson 1886). There is still no mention made about the caribou remains sent by Mackenzie.

Later, Henry Alexander Collison (June 14, 1876 – Jan. 30, 1948), wrote about the introduced animals and mentions the caribou:

“My father [William Henry Collison], who lived at Massett for three years, 1876 to 1879, …It was he who first conceived the idea of importing deer from the mainland, chiefly as an economic measure. On one of his visits to the mainland, he offered to purchase a few of these animals from the Tshimshean hunters. Seven were obtained in this way, and another, which was captured by a steamer on the voyage up the coast, was afterwards added. The Hudson’s Bay Company carried them over to the Islands, free of charge. They were liberated, and for several years increased steadily under the protection of an officer of the company, who succeeded the first trader. But, after his death the Haidas shot them off until they were exterminated. Another attempt, but on a much larger scale, was made about the year 1924. As these were strictly protected, they have increased to such an extent that in some areas they have become almost a pest. But what was so strange was the existence on Graham Island, in a vary limited area, of a distinct species of caribou” (Collison 1945).

1900

In 1900, “artist-naturalist” Ernest Seton Thompson (Aug. 14,1860-Oct. 23, 1946), who gave the name to the Mountain Caribou (Rangifer tarandus montanus), visited the Provincial Museum. He wrote about and gave the species name Rangifer Tarandus dawsoni to the Dawson caribou. He was in Ottawa in August 1899, after his “attention was called by Dr. G. M. Dawson, of the Geological Survey, to the fact that Caribou exist on the northernmost and largest island of the Queen Charlotte group”. Thompson corresponded with Dawson who had received information on the caribou from William Charles of Massett. Two weeks after his visit to Ottawa Thompson was back in Victoria where he interviewed William Charles at his home on Fort Street:

“Mr. Charles was Hudson Bay Co.’s factor at Victoria for years. and the Queen Charlotte Islands came within his official district. He informed me that while visiting at Masset in the north end of Graham Island, he several times heard reports that Caribou were found on the island. But the Indians never brought any in, for they have a superstitious dread of the interior and of the west coast, where the Caribou are found.

They believe that if they go there, they will be devoured by some fabulous monster that comes up from the sea. At best they are poor hunters, and rarely think about the chase when they can get a meal of fish. One day in 1882 (?) when Mr. Charles went as far as the west slope of the mountains on the Pacific side he noticed a great extent of beautiful level upland pastures, and remarked that if there are any Caribou on this island this is the place to look for them. Accordingly, Mr. Alexander Mackenzie, an ex-employee at the Hudson’s Bay Ca., set out with some Siwash Indians and found near the place a large herd of Caribou, and opened fire an them. The first to fall had only one horn. They brought its skin and skull to Mr. Charles, who states that the skin was of’ a mouse colour and the animal too small for the Woodland Caribou, and too dark to be the arctic species. He is of the opinion that it is closely related to the Barren Ground Caribou. The skin was destroyed, but the fragmentary skull with its one antler as deposited in the Provincial Museum of Victoria, B.C.

Dr. Dawson has called my attention to the following passage in Mackenzie’s Notes on Certain Implements and Weapons of’ Graham Island. (Trans. Roy. Soc. Canada. Sec. 11, 1891, P. 50). [Shown here in figure 3].

‘Reindeer antler Tomahawk (Haida, Scoots-hlth-at-low) [No. 1302] -This very ancient and interesting relic is made from antler of a species of Reindeer which inhabits the mountainous interior of Graham Island. In ancient times these Reindeer were hunted by the Haida and killed by bow and arrow, being highly prized both for meat and skin. This weapon was the property of the Masset doctor, or medicine man, who is still alive but aged. To him it was bequeathed by his predecessor who died many years ago…It is undoubtedly a relic of the times before these natives had intercourse with white men’ (McKenzie 1892).

Through the courtesy of Mr. John Fannin, I have had the opportunity of making a thorough examination of the skull in question and am convinced that the animal is entitled to formal recognition. I propose therefore to name it in honour of Dr. G. M. Dawson of the Canadian Geological Survey, the eminent explorer of the Queen Charlotte Islands, who first called the attention of the scientific world to the existence of the animal. [John Fannin was a curator at the Provincial Museum from 1882 to 1904, with a specialty in taxidermy].

“RANGIFER DAWSONI, Sp. nov.

Sp. Character, – Its small size, about that of Rangifer arcticus, and its color, which is darker than that of arcticus, but much lighter than that of montanus from the interior of British Columbia.

Habitat – Queen Charlotte Islands. The type being from the interior of Graham, which is the northmost large island of the group.

The nearest point on the mainland where Caribou are found is 150 miles away in the interior of British Columbia.

This individual was peculiar in having but one horn, but this is merely an accident and is probably the reason that the specimen was brought in by the hunters.

The following measurements will be of use in conjunction with the figures :

In figure I, the length of the antler from below the burr following the outer curve to the top of the highest point, 28 3/4 inches (730 mm) ; girth of antler at base above the burr, 4 3/4 inches (120 mm). In figures 2, length from the point of’ the occiput A to the posterior point of’ the nasal bones B, 6 9/16 inches (166 mm); greatest width across the orbits C. D. 6 inches, (153 mm.)

My thanks are due to Dr. J. A. Allen, of the American Museum, for the opportunity to compare its skull with that of its giant relative Rangifer montanus”.

1901. The Evidence and the Doubt.

Daily Colonist January 21, 1901.

“Who Knows? – Officials of the United States department of agriculture have addressed inquiries to the deputy minister of agriculture, Mr. J. R. Anderson, asking him if he can furnish information as to whether caribou exist on the islands in the Queen Charlotte group. Mr. Anderson has no special knowledge on the subject and would be glad if some one would answer the inquiry. It is alleged that some years ago a caribou was killed by the Indians on Queen Charlotte Island and the head sent down by a Mr. McKenzie to Mr. Charles, of the Hudson’s Bay Company.”

On April 8, 1901, anthropologist Franz Boas, of the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, sent a telegram to Charles Newcombe to offer $150 for an adult male and $50 for a young male or female caribou (Boas 1901).

Daily Colonist July 16, 1901.

Under the titles: “Caribou on Northern Islands. Resident on the Queen Charlotte Offers to Prove That Animals Are There”, the editor of the Daily Colonist comments and publishes a letter written April 30th by Charles H. Harrison of the Anglican church (1883-1916) of Massett, to James Robert Anderson, Deputy Minister of Agriculture:

“Some months ago, the provincial department of agriculture received an inquiry from the United States department of agriculture regarding the truth of a statement that caribou were to be found on the Queen Charlotte Islands; weather a caribou head had been sent from the Islands to a Mr. Wm Charles, [William Charles 1831-May 21, 1903] of Victoria, and weather the department could verify the existence of such head. Mr. Anderson, deputy minister of Agriculture, was unable at the time to secure the required information and he referred the matter to the Colonist, hoping that some reader of the paper would be able to throw some light on the subject. The Colonist query ‘Who Knows?’ elicited a letter from ‘one who knows’, who said there were no caribou on the Queen Charlotte Islands; that a few had been taken there by Indians from the mainland and turned loose, but that the animals had been killed by dogs. This was regarded as an unlikely story, as the Indians as a rule do not encourage the breeding or propagation of wild animals, and the difficulty of transporting the brutes across the straits would be attended with more difficulty and danger than they would care to endure.

Subsequently, however, the head alluded to was identified and it is now in the possession of the Natural History Society and may be seen in the societies room in the parliament building. As a sequel, Mr. Anderson, yesterday handed the Colonist the following letter, which positively verifies the existence of caribou on the islands”.

The letter to James Anderson reads as follows:

“Sir: I noticed a paragraph in the Colonist under the heading ‘Who Knows?’ re: the evidence of caribou on the Queen Charlotte Islands. I have lived here 20 years and know the account given is quite correct. I have made diligent enquiries the Indians, and have gained the following information:

1. Three years ago an Indian named Shakwan saw a female caribou feeding near a lake up Virago Sound, but failed to kill it, although he fired twice. Yethgwanus, another Indian. was with him at the time.

2. This March, a man named Stlinga, with his two sons saw the tracks of a big herd near the headwaters of Malon River, near Virago sound.

3. Men that were with the man who killed the two referred to in the Colonist are ready to show me the place where he killed them. This is near Lthuai on Virago Sound.

4. The Haidas refused to eat the flesh of the caribou and left their carcasses. Mr. Mackenzie then paid them to go and bring the meat in and kept it for his own use.

5. As the Indians are not interested in killing the caribou, they refusing to eat the meat, and there being no market for the antlers, etc. , they consequently do not hunt them. They say they are afraid to go up the mountains and into much danger without recompense, there being, according to their traditions, one eyed monsters, hobgoblins, spirits, etc., to be met with on the mountains they frequent.

In order to be sure caribou do exist, the United States department of Agriculture ought to unite with that of British Columbia and make me a grant of $250 to cover expenses. The Natural History Society of British Columbia ought also to assist. I would then get three good hunters, and visit every locality where they are reported to exist and make a thorough search. This would take about six months. Should we get any the heads would be kept and shipped to your department. I would not go until the middle of September, when my official duties as custom officer and fisheries overseer would be over until December.”.

After the above was printed in 1901, Biologist, Wilford Osgood (Dec. 8, 1875 – June 20, 1947), who had a caribou named after him, choose not to believe that evidence as it stood:

“The description of a caribou from the Queen Charlotte Islands to say the least, somewhat unexpected, so in visiting the islands I was particularly interested in obtaining information in regard to it. I could find no evidence, however, that native caribou ever existed on any of the islands. Rev. Mr. Keen, who lived at Massett for eight years, and who was specially interested in matters pertaining to natural history, says that from his own experience and that of the oldest Indian hunters, whom he questioned closely, he is decidedly of the opinion that no caribou are to be found in any part of the islands. Rev. Mr. Collinson, who was one of the earliest missionaries at Mas- sett, has the same belief as Mr. Keen, though he did not express such definite conclusions. Besides the missionaries I also interviewed a Mr. Stevens, who has kept the general store at Massett for the past nine years, and obtained from him the same opinion. All these per- sons are familiar with the story of ‘Mackenzie’s caribou,’ which is doubtless the cause of the mistaken idea that a peculiar species is native to Graham Island. According to this story, which was told me independently and without essential variation by Messrs. Keen, Collinson, and Stevens, some fifteen or twenty years ago Mr. Alexander Mackenzie, a trader for the Hudson Bay Company at Massett, conceived the idea that in such a favorable place as Graham Island there must be deer and caribou, though the Indians had never killed them or even seen their tracks. Accordingly, he offered a reward to anyone who should kill one or bring him evidence of having done so. The offer remained open for a long time, but finally a claimant appeared with fragments of a caribou, including the head. This imperfect specimen passed through several hands and finally found its way to the Provincial Museum in Victoria, where it was unearthed to receive the name Rangifer dawsoni. If the reward was incident to such a statement the Indian who brought this specimen to Mackenzie no doubt solemnly averred that he killed it on Graham Island. An Indian’s testimony in a case of this kind, however, would not hang very heavy in the balance, even against a small amount of circumstantial evidence. Mr. Mackenzie is not now living, but the testimony of Mr. W. Charles, who received the caribou head from him, indicates that for its absolute origin we have the word of the Indians only. In response to a letter to Mr. Charles I received an answer from Mr. J. R. Anderson, deputy minister of agriculture at Victoria, from which the following is extracted:

Some time ago Mr. W. Charles, who is an invalid, handed me your letter of the 10th January last regarding the occurrence of caribou on Queen Charlotte Islands. Mr. Charles asked me to communicate with you and say that the head referred to, and which had deformed antlers, undoubtedly came from Queen Charlotte Islands, having been sent to him by the Hudson Bay Company agent there, and was equally that of a caribou. The animal, Mr. Charles has no reason to doubt, was actually killed by the Indians, and they being unacquainted with it, brought the skull to Mackenzie, and reported more of the same kind in the interior of the island.

From this it seems that all the information in regard to the Mackenzie specimen came from the Indians, and that no white man has given direct first-hand testimony as to its absolute origin”.

Osgood mentions and quotes the Colonist article above forwarded to him:

“This, though much more definite than any other report received, contains little which did not emanate from the Indians, and it is there- fore difficult to be certain that it contains any element of reliability. Surely men who believe in “one-eyed monsters, hobgoblins,” etc., could easily indulge themselves with an imaginary caribou. However, Mr. Harrison’s statement that meat was brought to Mackenzie and used by him is much more worthy of consideration and might lead one to entertain a belief in the possibility that caribou were killed on Graham Island, but the probability that such was the case is still doubtful.

If the type specimen of Rangifer dawsoni originally came from the mainland, as seems probable, instead of from Graham Island, it may either have been deliberately bartered for with the intention of obtaining a reward, or it may have been innocently brought to the islands to be used in the native arts. More or less communication has always existed” (Osgood 1901).

Reverend J. H. Keen (1851-1950), in 1906, changed his mind about the existence of the Dawson caribou in a letter to Charles Newcombe where he wrote: “How extraordinary was the discovery of Dawson’s Rangifer on the Q.C. Islands! I had for years so stoutly denied the existence of deer there that the discovery brought me great personal humiliation”(Keen 1906). It is interesting that Keen, who had an interest in natural history, published on the subject and who has a mouse species, Sitomys keeni, named after him (Sealy 2015), did not look further into the existence of the Dawson caribou.

1905

Henry A. Collison sent a letter to the Victoria Daily Colonist on March 11, 1905, titled “Caribou on Graham Island”.

“During a wild fowl hunting expedition to Naden Harbor, Virago Sound, recently, I took it into my head to pay a Visit to the reputed haunts of that – as I then supposed – shadowy and mysterious animal, the caribou; with the object of proving to my own satisfaction whether there was any truth in the rumor that caribou were to be found on this island. Ever since my arrival at Massett, two months ago, I had heard a great deal for and against the existence of caribou on these islands The old Indian hunters, without exception, were positive on the point, as several of them had seen and fed on them; and one old fellow had actually helped to pack out the flesh of a big animal that his companion had killed, eighteen years ago. The young men, on the other hand, like most young people, were sceptical, and I must confess I sided with them; not that I was guilty of forsaking the counsel of the old men, but because I attached considerable importance to the view held by white men who had spent many years on the island, one of whom was especially interested in the study of natural history. Nearly all denied that there was any truth in the report. I was also influenced by the difficulty: Why, if there were any caribou on Graham Island, had they not been seen in greater numbers, seeing that they had the whole island to themselves, and there are no wolves to prey upon them? I am totally unacquainted with the habits and natural characteristics of the caribou, but I should say they have had ample time to multiply.

The existence of the caribou on this island was known and referred to by old hunters thirty years ago, and they must have been here ages before that, since it is most unlikely that they were imported by human hands.

In the face of conflicting and unsatisfactory evidence, I was determined to seek answers for myself. Consequently, on March 3, 1905, I left the little nine-ton schooner, anchored off the old Hydah village of the Kung, at the entrance of Naden harbor, and in company with two Indians proceeded along the shore of Virago Sound in a northeasterly direction for nearly three to 10 miles. At this point, marked by a huge moss-covered boulder, we determined to strike inland. According to my compass the direction we took lay due west. The appearance of the bush was not inviting: great fallen trees lay about in all directions, in some places piled one on top of the other. Fortunately, this state of things did not last long, as after a steady tramp of about an hour, during which we crossed a range of hills, we emerged upon a rolling swamp, a mile long by a quarter of a mile broad. we found, was literally covered with large tracks, not unlike those of cattle, making due allowance of course for the swampy nature of the ground, which does not register a correct impression.

Many of the tracks were quite fresh, and I don’t think I am mistaken when I say the animals must have been there that morning, or at any rate the evening before. We came upon many such open swamps. In the course of the day, separated from each other by narrow belts of timber, with a thick underbrush of salal bushes.

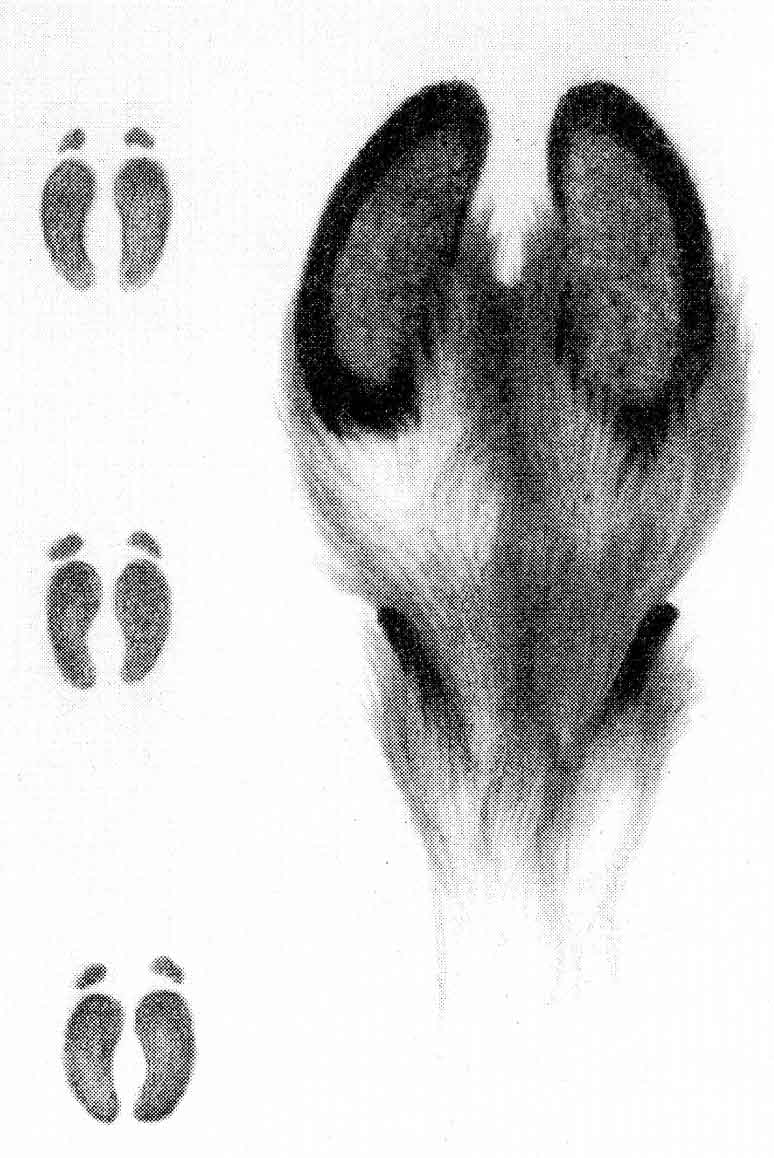

Experienced hunters identified caribou tracks (Figure 6) and dung on Graham Island on many occasions without seeing any caribou,

We had come prepared to spend a night in the woods, as if the caribou at all resemble the common red deer in their habits, they would abroad at sundown, atter their long among the trees or on the hillsides–the very early morning is perhaps the best time. But my Indian companions did not ap of pear to relish the prospect of a night in he the swamps, especially as they had read the sky and declared it was going to be a fearful night. We just had time to reach the beach before dark. Personally. I never did enjoy a night’s rest in the woods with only one blanket and no tent; so i rather readily fell with the proposal. At the same time I was loath to leave the caribou country before completely establishing my proof.

But I am satisfied. There are caribou on Graham Island, whether few or many I am not prepared to say as yet. The fall of the year would be the best time to find out, as then the animals are in good condition, and should there be any show, it would be comparatively easy to track them to their haunts.

The tracks 1 saw were not those of deer. as I know something about deer, having hunted them frequently on the Mainland. These and other unmistakable signs have shown me conclusively that the old Hydah hunters were right after all” (Collison 1905).

1906. Finding an Antler

In December of 1905, prospector J.H. Coates, while prospecting west of Virago Sound found tracts and scats which he thought were elk, but got Kermode thinking caribou (Kermode 1906). In early 1906, the Museum curator, Kermode (June 28, 1874-Dec. 29, 1946) asked the officers of the Naval ship HMS Shearwater to make some investigations when in the vicinity of Massett. “They found no caribou, but they did find some tracks, and they brought back to the curator a shed antler [found February 22] which they picked up, and some droppings. These presented clear proof that the animals did in point of fact, exist” (Daily Colonist 1909).

A talk was presented to the Natural History Society of British Columbia by the officers of the Shearwater, Commander Hunt & Lt. Bills R.N. on: “Finding of Carriboo on Graham Island”. The Secretaries Report, of March 5, 1906, noted: “The paper on the finding of carriboo on Graham Island may be pointed out as of exceptional interest as it conclusively proves their existence on that island, whereas it has always been stated that neither carriboo or any of the deer family inhabited any of the Queen Charlotte Island group” (RBCM MS-0284 NHS Minutes. Vol. 2, 1906).

Figure 7, shows, RBCM 1488, the Dawson caribou antler collected by Commander Hunt and Lt. Bills, officers of the HMS Shearwater.

After hearing of the caribou antler find, the big game hunter, explorer and conservationist, Charles Sheldon (17 Oct. 1867 – 21 Sept. 1928), headed off on a trip to Graham Island in Haida Gwaii: “for the purpose of investigating the occurrence of caribou which were supposed to exist there.” He spent October 26-November 23, 1906 in the region around Haden Harbour. In 1911, Sheldon wrote a chapter in his book: The Wilderness of the North Pacific Coast Islands. A Hunter’s Experience while Searching for Wapiti, Bears, and Caribou on the Larger Coast Islands of British Columbia and Alaska (Sheldon 1912).

Sheldon reported: “In March, 1905, Mr. Harrison himself and the Rev. H.A. Collinson, the missionary stationed at Massett, who was the son of the Mr. Collinson interviewed by Osgood, took five Indians and spent ten days in the woods near Virago Sound. They reported that they saw abundant caribou tracks and dung and picked up some caribou hair. The following April, Henry Edenshaw, son of a former chief of the Haidas, went into the same country and likewise said that he saw tracks and dung”.

Sheldon arranged with Charles Harrison to undertake a search. He pointed out that Harrison “formerly missionary for twenty years among the Haidas as Massett, speaks the native language fluently, and knows more about Graham Island than any other man”. On October 27, 1906, Sheldon reached the Haida village of Massett. For the trip Sheldon “employed a half-breed, Robert Brown, and Mr. Harrison’s son Percy”. On the 29th he “lunched with Henry Edenshaw, and spent part of the afternoon visiting many Indians discussing the caribou question. I found that all were familiar with the fact that tracks were abundant near Virago Sound but none of whom I talked had seen a track, nor did the Haidas have any traditions about the animal. Elthkeega, an old Indian, then dead, had owned a few dogs that would chase the bear, and I learned that those dogs once drove a caribou bull and cow into Virago Sound, both of which Elthkeega had Killed. That bull was the ‘Mackenzie caribou’. Those who read this narrative will wonder how it could be possible that these Indians had never seen a caribou on the island. I still wonder at it. The Indians have always gone into the Interior along the rivers, to set traps for bears or martins, also to get trees for their canoes, and occasionally they have crossed the Island to the west coast.”

As Sheldon travelled through the glades and meadows on October 31, he saw: “passing along the edge of the woods, the distinct tacks of a caribou. Soon I found dung which did not appear to be old, and it was an intense satisfaction to realize at last that the caribou on Graham Island were not imaginary”. Sheldon continued the search until November 22, after which he commented: “I had not even seen a living mammal, though I had completely circled the area within which the caribou tracks were visible. The only tangible result of my trip was to bring back a small bottle of dung as proof that caribou were really there”.

1908-1909. The Last Seen Alive

The Victoria Daily Colonist reports on October 22, 1908, that the steamer Vadso was making a trip to Masset with the passengers “Hon. Dr. Young, minister of education; Frank Kermode, curator of the Provincial Museum, and S. Whittaker, who go in search of the Caribou reported to have been found in that vicinity. They will leave by the steamer Princess Victoria on Monday and will embark at Port Simpson or Prince Rupert on the Vadso (Colonist 1908). The next year it was reported “Unfortunately he was unable to get a boat to take him across to Prince Rupert during the time at his disposal, and while he was waiting there the three specimens were shot”. (Colonist 1909).

On November 1, 1908, Haida from Massett, Mathew Yeoman and Henry White were hunting “in a large swamp-barren three or four miles inland, midway between the mouth of the Naden River and Kung …they saw four Caribou – two bulls with horns, a cow, and a calf” (Sheldon 1912). The three adults were killed and the skins and skulls were sent to the Provincial Museum.

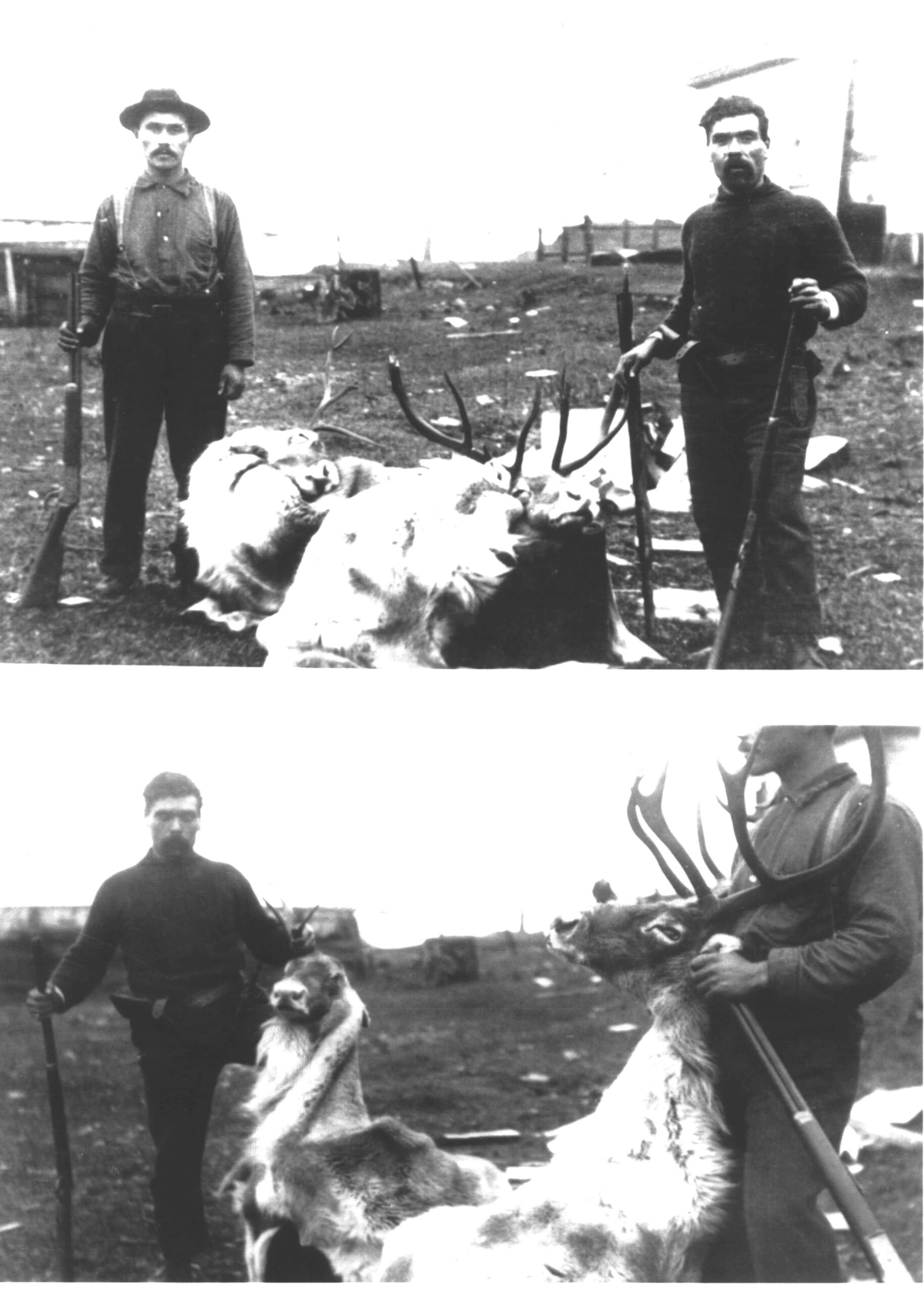

Figure 8, shows Mathew Yeoman and Henry White with two of their three kills. Caribou head being held up on lower right and on upper right became RBCM 1486. The specimen on lower left and upper left became part of mount RBCM 1484.

In his “accession notes” Charles Newcombe noted: “Our congratulations are extended to Captain Henry White on his notable contribution to the Natural History of British Columbia; he having being one of the party that collected our unique Specimen of the Queen Charlotte Caribou (Rangifer Dawsoni Seton-Thompson)”.

Henry White was the son-in-law of Charles Edenshaw (1850-Sept. 10, 1920) according to Charles Newcombe (1902). He was marred to Emily Edenshaw and his son was Rufus White, married to Rita Price.

On December 31, 1908, the Victoria Daily Colonist headlines: “Caribou Heads Come From Graham Island. Curator Kermode Pronounces Them to Be a New Species”. They note that the Museum has received the hides, skulls and skins which Kermode pronounces: “to be beyond all question a new species of caribou. …although it is probable that the differences are largely the result of excessive interbreeding. The trophies received by Mr. Kermode consist of the hides of two bulls, and their skulls, and the hide of a cow. The hooves and head of the latter animal, however, are lacking so it is of no practical value. Judging from the specimens received the Queen Charlotte caribou is a small specimen of the genus, the full-grown animal probably not being larger than a mule deer and weighing about 250 pounds. The antlers present marked divergence from the ordinary type. The ploughs so familiar with caribou heads are absent, the there are very many fewer tines. In fact, the whole antler is smaller and less massive than on the mainland caribou. The hides are nearly white with only a little brown showing, which is also a result of excessive inbreeding.

One of the animals is an old animal as his teeth show. The incisors are gone and the molars worn down. The other is younger and smaller and boasts one antler. The missing antler has not been broken off, as examination of the skull revealing the fact that it never had one. This again is a result of inbreeding, and the only hope of preventing the extinction of the band, which is now a small one, is the introduction of fresh blood from the mainland. Half a dozen young bull caribou from the mainland would, according to curator Kermode, by introducing new strains of blood prevent the further degeneration and ultimate extinction of the newly discovered species”.

The Colonist goes on to note: “Owing to a misunderstanding the trophies were delayed in route, and as the hides were badly skinned and treated it will be a difficult matter to stuff and mount them properly. Mr. Kermode, however, intends to see if this cannot be done” (Daily Colonist 1908).

Kathleen Dalzell, of Prince Rupert, added to the story of the killed caribou. She acquired information from Norman Broadhurst (Oct. 13, 1877-Feb. 7, 1966), a retired Sea Captain. Frank Kermode, the curator of the Museum, appointed him to obtain a Dawson caribou. Broadhurst went to Massett where he met “Mathew Yeomans, who told me that he and Henry White had two caribou at his house. I was invited to have some of the meat. The animals had been skinned and slightly smoked to preserve them. The skin looked pretty good to me, but they had been cut off at the knees. However, I got hold of them and wrote to Kermode, as these two Haida hunters were doubtful I would get anymore they were so scarce”. But Kermode told Broadhurst that he didn’t want them as they had been cut up and sent him to try to hunt some on his own. “It was hopeless” says Mr. Broadhurst, we looked all over the Naden Harbour area where they were supposed to be – and walked down the west coast as far as the old drill at Tian Point – walking along the top of the cliffs and beaches from Kiusta. “In the end the Museum took the two scorned hides and using the small specimen secured in 1906, were able to compose the caribou now on exhibit at the Provincial Museum – three animals to make one”. (Dalzell 1968).

Figure 9, shows two views of RBCM 1486 seen in lower right part of image 8. The photographs were taken by C. Hart Meriam and printed in Sheldon in 1912.

Figure 10, shows the damaged antler mention by Banfield on RBCM 1486. I took this photograph on April 29, 2016.

Figure 11, shows the Dawson caribou RBCM 1486 from the bottom with the cut off posterior and damaged front end.

Figure 13, shows a comparison between the small RBCM 1486 mandible and an average male mountain caribou RBCM F77-38-10441.

1911 – 1912

In the fall of 1911, Clinton Hart Merriam (Dec. 5, 1855 – Mar. 19, 1942), Chief of the Division of Biological Survey of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, visited Francis Kermode at the Provincial Museum to examine the 1908, caribou specimens before they were mounted. Merriam was a zoologist, ornithologist and entomologist who helped organized the famous Edward Harriman Expedition, that explored the Pacific coast from Seattle to Siberia in 1899.

Merriam’s report “The Queen Charlotte Islands Caribou, Rangifer dawsoni”, was published as an Appendix in Sheldon’s publication (Sheldon 1912). It is repeated here without the detailed cranial measurements:

“The most striking characters of the species are small size, imperfect development of antlers, and absence or indistinctness of the usual color markings. Throat mane feebly developed, reaching from throat nearly to forelegs, longest in middle, longest hairs 6 in. (150mm.).

Color and Markings in Fall Pelage (November). – Coloration remarkably uniform and pale throughout, the usual dark areas indistinct or absent. General body color drab; top of head form edge of nose pad to horns, pale drab chocolate; top and sides of neck pale drab gray varying to buffy whitish, followed on shoulders by darker drab, but without trace of ‘cloak’; shoulders, upper half of back to tail, and outer side of thighs drab; flanks grayish, with indication of dark horizontal band below (just outside of white of belly); fronts and outer sides of legs and thighs paler drab, slightly paler than back; under side of tail whitish; rump patch absent, but sides of rump posteriorly, below plane of tail, faintly paler than above; nose pad, lips, ring around eye, ears, chin, throat, and ankles whitish; no markings on feet or ankles, the whitish of these parts passing insensibly into the pale drab of the legs.

Young. – The young cow is a little more strongly marked than the adults: dark color of head reaching farther back (to occiput); back and rump darker; flank band slightly more distinct.

Antlers. – Small, short, and poorly developed, with little if any flattening of the brow or bez tines (or elsewhere), and few “points.” Brow and bez times with normally 2 prongs each, one of which is sometimes forked, making 3 points; trez tine rudimentary or absent; tip usually forked, sometimes 3 pointed.

The antler may be straight (as in this type) or curved strongly forward (as in the old bull with largest horns). In the type specimen it (right antler) measures 695 mm. in greatest length in straight line. In the old bull the left measures on the curve 36 ½ in. (928 mm.); the right 32 ½ in. (825mm.). The single antler (left) found by Commander Hunt measures on the curve 35 in. (890 mm.).

Skull. – Small and light compared with neighboring species; orbital rim prominent, its upper part deeply emarginated (cut away anteriorly); orbital border of lachrymal markedly and rather acutely convex; frontals strongly depressed between centres of orbits, behind which they rise abruptly to form a conspicuous thickened median ridge; under jay light and slender; angle feeble; coronoid light.

Cranial Measurements of Old Bull* (* Skull imperfect, the hinder part sawed off so that total and basal lengths cannot be obtained).

Description based on the type and four other specimens in the Provincial Museum, Victoria, B.C., which I was allowed to examine by the courtesy of the curator, Mr. Francis Kermode. – C.H.M.” (Sheldon 1912).

Figure 14, shows a painting of the Dawson Caribou set on an open landscape.

1919 – 1961. The Last Attempts to Find the Caribou

The belief that the Dawson caribou still existed in 1919, can be seen in the caribou hunting regulations. It was allowed to hunt caribou bulls “only over one year old throughout the Province – except on Queen Charlotte Islands” (Daily Colonist July 31, 1919).

On December 19, 1919, the Provincial Museum director Frank Kermode wrote to Haida, Henry White at Naden Harbour, Haida Gwaii:

“In reply to your letter of December 12th, re Queen Charlotte Caribou, I am afraid that it is too late this year to do anything in regard to getting specimens, as it will be a very short time before these animals will have shed their antlers, and they would practically be no use for mounting purposes. However I will keep this matter in mind, and you may hear from me again some time next Fall. I would be very pleased to hear from you if you have seen many, of these animals, since the three you killed several years ago, on the west side of Virago Sound”. (Provincial Museum 1897-1970). BCARS GR111 Box 44 file 1-6.

Biologist, Ian McTaggart Cowan of the Provincial Museum visited Haida Gwaii in 1935, and was told by Henry White, who collected the 1908 specimens, that fresh tracts were seen in the last two years (Cowan 1936).

In 1936 Ernest Seton Thompson produced: Type Specimens of Mammals in The British Columbia Provincial Museum. Queen Charlotte Island Caribou (Seton-Thompson 1936):

“Type: -Adult male, B. C. Prov. Mus. No. 1483, fragmentary skull consisting of cranium to front of orbits and lacking the occipital condyles, basioccipital, maxillae, and entire rostrum; right antler only, left pedicle diseased. Taken (?) 1882 by Alex. Mackenzie and presented by Wm. Charles.

Type Locality: Upland meadow on the west slope of Graham Island, west of Massett. Queen Charlotte Islands, British Columbia.

No. 1486, adult male, skull only; west side of Virago Sound, Graham Island, Q.C.I. November 13, 1908. Since Merriam (loc. cit.) described and figured this skull it has been badly broken. The rostrum and entire maxillary region with the teeth are now missing along with the occiput and both zygomata. Taken by H. White.

No. 1487, skin of young female in good condition; taken by H. White on west side of Virago Sound, Q.C.I., November 13, 1908.

No. 1488, shed left antler, picked up by Commander Hunt and Lieutenant Bills, Feb. 22, 1906, on the uplands on the west side of Virago Sound inland from Hussan Point (see Ottawa Naturalist, 19, July 1906:73-76).

As external measurements of this caribou were not given in the previous descriptions the following, as taken from the mounted adult male No. 1484, may be of interest: Total length 1910 mm.; length of tail 110 mm.; hind foot from point of heel to tip of dew claw 385 mm.; height at shoulder 1050 mm” (Seton-Thompson 1936).

On March 29, 1939, Kermode sent another letter to Henry White of Massett: “I have often wondered since seeing you here in my office last year whether you have had any information since then regarding the Queen Charlotte caribou. If you have reports at any time on these animals I should much appreciate hearing from you.” (Provincial Museum 1897-1970).

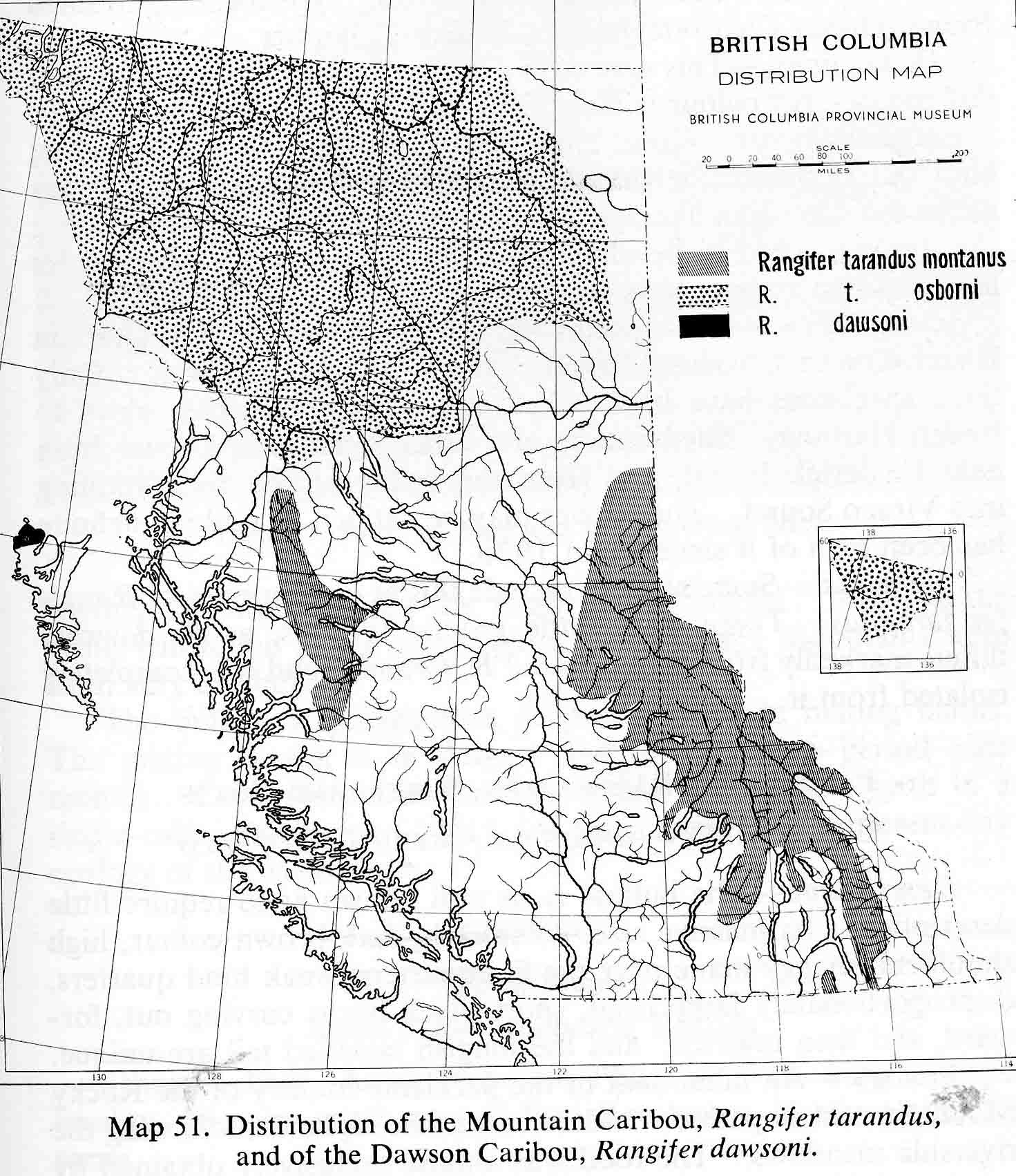

In May of 1948, a new professional biology, Charles J. Guiguet (1915-1999), joined the Provincial Museum staff. He had previously spent a few days each summer in 1946 and 1947, searching for signs of the caribou in the peatlands between Naden Harbour and Jalun River. Ian McTaggart Cowan and Charles Guiguet noted in their publication The Mammals of British Columbia in 1956: “This species may be extinct, as nothing definite has been seen of it since about 1920. …Some authors include this as a subspecies of Ranifer tarandus. There seems little ground for this, as R. dawsoni differs markedly from the mainland R. tarandus and was completely isolated from it” (Cowan and Guiguet 1956). However, again in 1957, Guiguet, with Donald Robinson of the Department of Recreations and Conservation searched the area on foot and by aircraft. In spite of saying the species may be extinct they include it in their map showing the distribution of both Mountain and Dawson caribou ( Figure 15).

Guiguet, after I had joined the Museum, wrote a letter on October 22, 1972, to overview the Museum Dawson caribou collections and provide his opinion as to how the caribou came to Graham Island. My discussions with him correspond with what he said in the letter:

“We have on index five specimens of Rangifer tarandus dawsoni numbered B.C.P.M.1483, 1484, 1486, 1487 and 1488. No. 1483. A skull fragment picked up near Masset, in 1882, Willian Charles of that city was described by Seton in the Ottawa Field Naturalist Volume 13, Page 260, 1900. This is the type specimen. Seton named the species after Dawson the early geologist. N0. 1484 is the skin and skull that was mounted (the skin and skull not necessarily from the same animal). No. 1487 is a skin only specimen. The No’s 1484, 1486 and 1487 are specimens taken by White in November 1908, we don’t have the exact day – apparently the hide (probable the one in best condition) from one animal was mounted with the skull from another. N0. 1488 is a shed antler picked up by a commander Hunt near Hussan Point, Virago Sound”.

Guiguet gave his view on how the caribou came to the Island:

“Caribou probably got stranded on the Charlottes toward the end of the Vason glaciation which covered the entire coast. The animals probably re-invaded British Columbia along the coast where the ice (probably again) went first due to the marine influence (higher temperatures). The Q.C.I, part of the coastal complex, was joined to the mainland by land and ice bridges over which the caribou crossed, and got stranded when those bridges disappeared. Coastal climate is inhospitable caribou habitat. The mainland animals moved out of it into the Interior as the ice went but the Q.C.I. animals could not do this. The individuals deteriorated due to the marginal range conditions, hence dwarfed bodies, dwarfed malformed and singular antlers. These attributes are common to caribou on marginal range, e.g. southern B..C. and Idaho – we have several specimens that resemble those from the Q.C.I. And so the turn of the century saw then on their last legs – the introduction of deer is probably the last shaft, for isolated populations are most susceptible to the diseases and competition”. (Guiguet 1972).

In spite of the declaration that the Dawson caribou was extinct, Biologist, Alfred Frank Banfield (Mar. 12, 1918-Mar. 8, 1996), proceeded with a foot and areal reconnaissance on Graham Island, from July 18 to August 12, 1961. Banfield, who started work in 1948 with the new Canadian Wildlife Service, had an interest in caribou habitat. His search did not locate any traces of caribou, but he observed their previous habitat, The same year, he published “A Revision of the Reindeer and Caribou, Genus Rangifer” to add to his other articles on caribou and the mammals of Canada (Banfield 1961).

One of the students that assisted him was J. Bristal Foster, who wrote a U.B.C. doctoral dissertation on: The evolution of the mammals of the Queen Charlotte Islands (Foster 1965). In 1968, Bristal filled the new position of assistant Director and in 1971, the Director of the Provincial Museum.

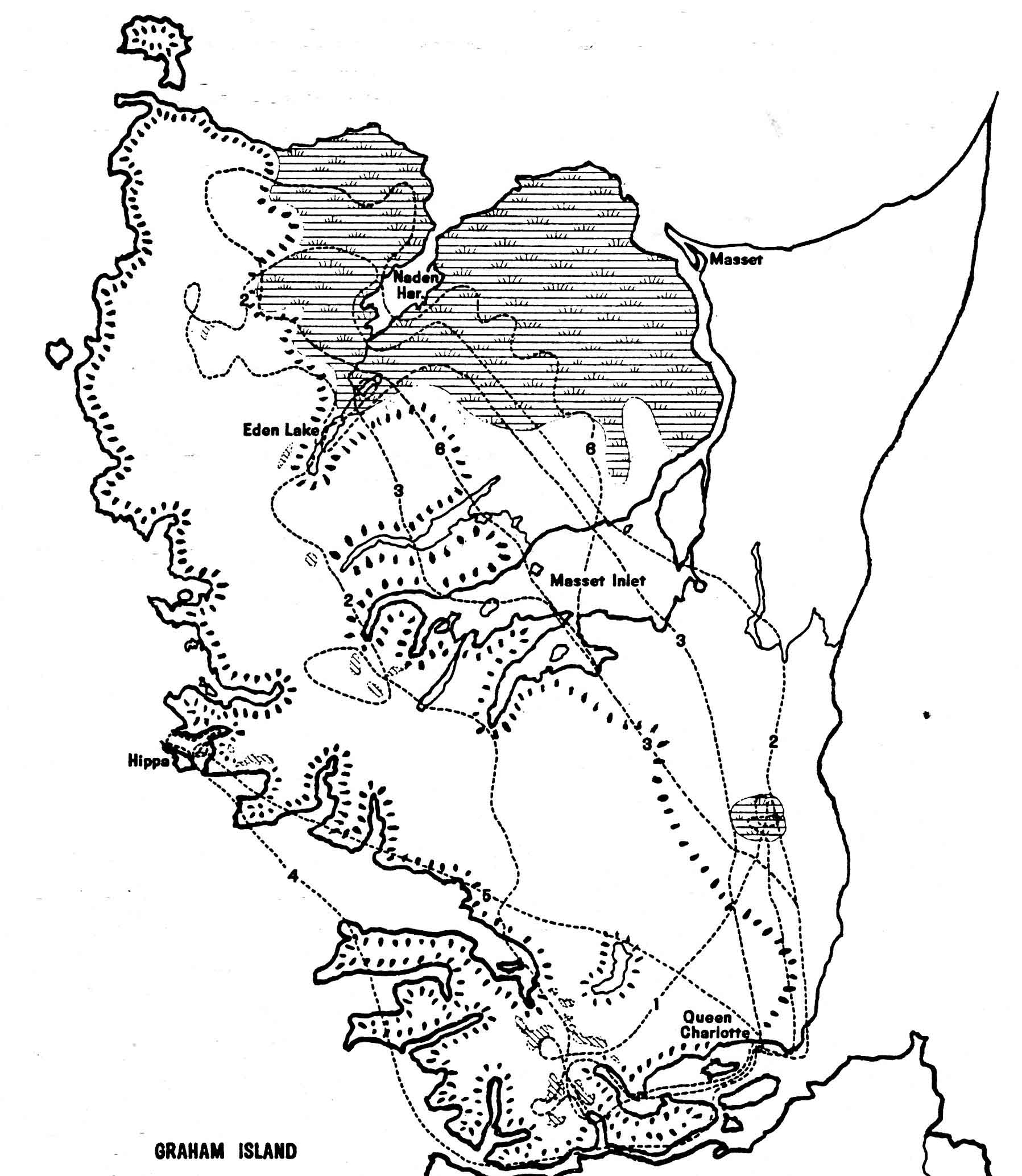

Figure 16, is Banfield’s map of Graham Island that shows the caribou habitat on both sides of Naden Harbour,

Archaeology

The basal portion of a fossil caribou antler (Haida Gwaii Museum acc. No. NM 17001) from White Creek on Graham Island dates to 43 200 ± 650 years BP (48 200 – 45 200 cal. BP). This is older than the Fraser (late-Wisconsin) glaciation on Haida Gwaii. It dates within the mid-Wisconsin Olympia Interglaciation period known as Marine Isotope Stage 3, MIS 3. Paleo-ecological analysis from Graham Island has reconstructed a vegetation cover during this time period. It consisted of mixed coniferous forest with non-forested openings, similar to cool subalpine forests of today. “These conditions are consistent with environments that support woodland caribou and the related extinct Dawson caribou. Morphometric comparison of antlers from woodland and Dawson caribou suggest that they are more similar than previously interpreted and raise questions about the inferred differences between the mainland and island subspecies” (Mathews et. al. 2019).

Kubiak et. al. undertook isotopic analysis of the White Creek caribou antler to determine the composition of the resources in its diet. The study employed compound-specific carbon and nitrogen stable isotope analysis to the individual amino acids of antler collagen. The stable isotope composition of bulk collagen from this antler, showed carbon and nitrogen values that are much higher than expected for a terrestrial herbivore. A significant contribution of marine resources to dietary protein was estimated to be approximately 23–41%. “Results suggest a significant marine plant contribution to the caribou’s spring–summer diet, potentially reflecting an intensive foraging behavior observed in some modern-day Rangifer tarandus populations under conditions of terrestrial resource restriction” (Kubiak et. al. 2021). .

The Last 14,000 Years

Human Presence

Domestic dog remains with a direct radiocarbon age of 13,100 years ago are the earliest indicator of human presence from cave assemblages. A small number of artifacts date back to 12,600 years ago. The stone tools that were found are predominately spearpoints and fragments thereof, which were used to hunt denning bears (Fedje et al., 2005).

There are no caribou recorded on Haida Gwaii for the long time period between 43,000 and 14,000 years ago. Although a brown bear has been found dating to 17,000 years ago in a non-cultural portion of the K1 site. 15,000 to 12,000 years ago the landscape of Haida Gwaii and surrounding continental shelf was biologically productive, with cool climatic conditions and diverse herb and dwarf shrub vegetation (Fedje and Mathews 2005). Significant warming occurred 12,500 B.P., when temperate climate plant communities began to replace the late glacial flora. The later became restricted to alpine sites and edge environments.

Karst cave investigations at three cave locations (K1, Gaadu Din 1 and Gaadu Din 2) recovered a paleontological record extending from ca. 13,400 to 11,000 years ago, which included both caribou and deer, black and brown bear (Wigen 2005). In the K1 site portion, used by bears for winter denning, there were three caribou bones, one dated to ca. 13,320 years ago. The cave was used by brown bear ca. 13,400 to 13,200 years ago and by black bear from ca. 12,850 to 12,300 years ago. Human made spears indicate that hunting likely occurred at the cave mouth and, occasionally, injured bears retreated to this inner chamber. Some of the caribou and deer remains were chewed by carnivores. These caribou bones fall within the size of modern woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus), rather than the small historic Dawson’s caribou. (Fedje et al., 2005).

What Happened to the Deer?

As Wigen points out, Haida Gwaii had a wide variety of fauna between 11,000 and 10,000 years ago, but brown bear and deer had disappeared after this. What happened to them? (Widen 2005).

In a portion of the K1 site used by bears, six bones have been identified as deer, one dating to 12,800 years ago. At Gaadu Din 1, seven dates on deer and deer-size ungulates, range between ca. 13,150 and 12,810 years ago. Deer may have arrived on Haida Gwaii during a time of climate amelioration around 13,500 years ago when low sea levels resulted in a very narrow separation (and possibly a land bridge) between the archipelago and the B.C. mainland (Fedje et al., 2005).

Although paleontological sample sizes are not large, the absence of deer younger than ca. 12,800 years ago raises the possibility of extirpation around this time. This timing is coincident with the beginning of the Younger Dryas cold interval, when from ca. 12,900 to 11,700 years ago the regional climate was wetter and much colder than present. Wet sage tundra at 13,200 B.P. gave way to coniferous forests about 12,500 B.P. This resulted in significant environmental changes that could have been disastrous for a cold-sensitive species such as deer (Mathews et al., 1993; Patterson et al., 1995; Hetherington and Reid, 2003; Wilson and Hills, 1984; Hanley, 1984).

Caribou 6000 to 2000 Years Ago.

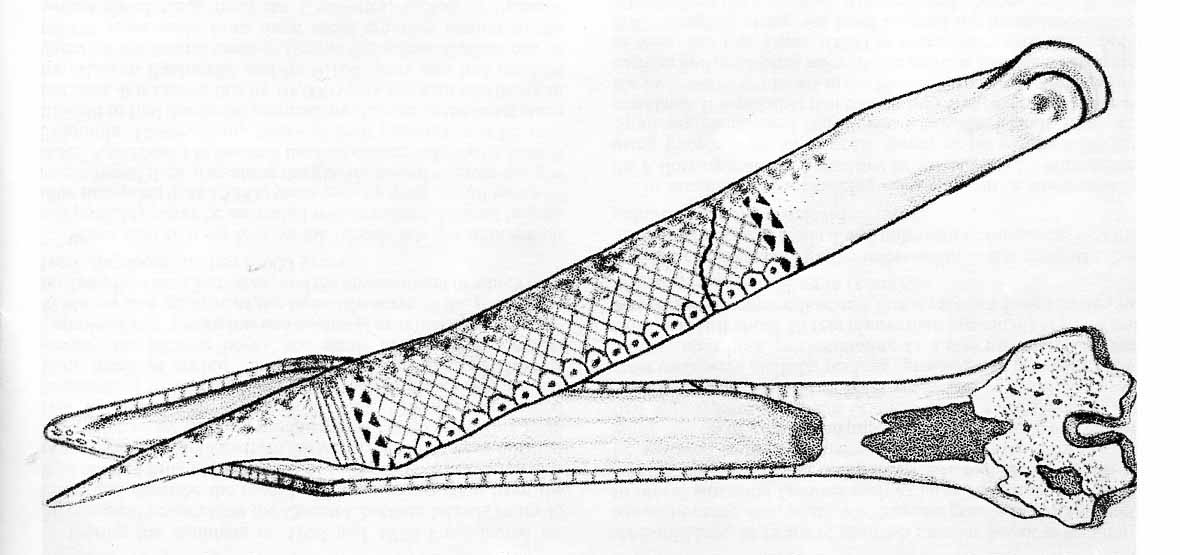

Caribou bones dated from 6000 to 2000 years in age have been found at several sites on Haida Gwaii (Severs 1973;1974;1975; Ham 1990; Christensen and Stafford 2005; Wigen 2005). Sites on Graham Island dating to about 4000-3000 years ago have significant numbers of caribou remains. So far, on south Moresby there are no post 2000 B.P. caribou remains (Christensen and Stafford 2005). What is significant is that the archaeological remains are much larger than their equivalent in comparison to the few recent Dawson caribou. These bones are similar to those of the large barren-ground caribou (Severs 1974; 1975). Two caribou metatarsal bones (Figure 16), from the Blue Jackets site FlUa-004, date to around 4200 years ago (Severs 1974).

DNA Study

A selection of 215 base pairs of mitochondrial DNA of the Dawson caribou was compared with those of Rangifer tarandus (woodland caribou) and Rangifer tarandus granti (barron-ground caribou). This analyses, suggested that the Dawson caribou was not genetically distinct. Three RBCM specimens, RBCM 1487, 1486 and 1483 were examined. Three long bone samples were also tested, two from the Blue Jackets site FlUa-004 and one from the Honna River site DfUa-15. None of the later produced any viable results. In examining the average interspecific differences measured, it was concluded that the Dawson caribou was not identified as a distinct lineage.

The authors note that: “Although we were able to sequence only a short section of the ancient DNA in the museum skins, which limits the robustness of the results, our confidence is increased by the lack of genetic differentiation between caribou subspecies found in other studies”. They, however, also suggested: “This lack of genetic differentiation may be due to high gene flow, retention of ancestral polymorphisms or a combination thereof. Resolving phylogenetic relationships within caribou will likely require broad analysis of longer sequences with many loci.” (Byun et. al. 2002).

This study was undertaken 22 years ago with a very small sample of mtDNA. Many advances in DNA research have show the greater need for whole, or more comprehensive genomes, when trying to understand variation in diversification rates. We know that diversity can be brought about by isolation with fast changing linages, but as in the case of the mammoths of Wrangle Island, genetic diversity may not be lost over a long period of time. If caribou continued to exist on Haida Gwaii from 42,000 years ago until historic times it might be difficult to predict what the temporal mode of genetic diversity might occur.

Since 2002, better methods of selecting specific bones and methods of processing DNA have been developed. The museum specimens that failed to produce viable results should be re-examined along with other archaeological caribou bones.

Discussion

The Dawson caribou are today defined as a sub-population or ecotype of the Mountain caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou) that range throughout the wet belt of the Interior of B.C. Unlike their northern neighbours their migratory movements are vertical moving from low elevation valleys and slopes in fall and early winter to subalpine areas in late winter and early spring. Mountain caribou are extremely well adapted to survive cold, snowy mountain winters.

We now know that the ice coverage was not as extensive as it was presented in the 1970s. We also know that the caribou found in archaeological sites over thousands of years were larger in size than those killed in 1908. This opens up a new window on how we might interpret the reasons the Dawson caribou became extinct. They were not a “dwarf species”. They were hunted regularly by, at least, some of the Haida before the19th century. There was an Indigenous presence on Haida Gwaii 13,000 years ago and probably a few thousand years earlier. More archaeological specimens are needed to examine the long term effect of humans on caribou diversity.

The reduction in caribou is likely a result of several factors that include environmental changes and the introduction of deer as expressed by Guiguet. Historic introduced deer had the option of moving into areas where there was no competition with caribou. However, they were observed in areas where evidence of caribou use was found and may have competed with the caribou for a variety of plants. If this included eating arboreal moss, it would have a larger effect on the caribou in the winter months.

David Lathem and Stan Boutis looked at the recent geographical range extension of White-tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus) as they expanded into northern Alberta, and discuss the potential ecological ramifications of their observation for Woodland Caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou). They observed that the White Tail deer were most abundant in the boreal forest in the well-drained upland habitat. The unusually large numbers of deer seen in a large fen complex were observed to be using arboreal lichen (old man’s beard; Bryoria spp. and Usnea spp.) as a winter food. This was not their practice further south and represented a new adaptation (Lathem and Boutis 2008).

The possibility that the deer introduced to Haida Gwaii in historic times adapted to eating the tree and ground mosses important to the diet of the Dawson caribou needs to be examined. Possibly in earlier post glacial times the Dawson caribou out competed the deer by eating more moss?

I would propose that an important factor in the demise of caribou in more recent centuries was cultural change. From what we know about Haida land and resource control, caribou hunting would be managed by individual extended families that would restrict the number of animals harvested. There may have been periods of warfare and disease where traditional patterns were disrupted. In later times the traditional practice was likely altered by depopulation of hunting families and more uncontrolled hunting with guns. As the Haida adopted European style clothes and weapons, caribou skins and antlers would no longer be a trade commodity. Caribou would become mainly a local food source by the mid 19th century.

Another factor is the unknown effect of land mass changes from sea level increase and decrease on caribou population capacity. A period of low sea levels during late Pleistocene time between 13,400 and 11,000 years ago, was followed by a transgression that culminated about 7500–8000 years ago when the sea was about 15 m higher relative to the land than at present (Clague et. al. 2007).

Is the Dawson Caribou Endemic?

The glacial environment extended from 21,000 to 17,000 B.P., but how far it extended along the coast is still an ongoing subject of investigation. In Southeast Alaska ice free conditions existed from 24,000 – 17,000 years ago at On Your Knees Cave (49 PET-408, Prince of Wales Island (Heaton and Grady 2003). The peak of the glacial period is currently seen as being in a range from 17,000 to 14,500 B.P. (Carrara P.E., Ager T.A., and Baichtal J.F. 2007).

Banfield (1961) and Foster (1965) surmised that woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou) arrived on Haida Gwaii during early postglacial times, when lowered sea levels allowed access from the adjacent mainland. It was believed that Dawson caribou could not have survived the period during the height of glaciation.

Conclusion

The factors that led to the final demise of the Dawson caribou on Graham Island would have likely included competition from historically introduced deer, the disruption of traditional Haida land resource management, the introduction of guns, the sport and hunting mentality of the non-Indigenous world and the ignorance of animal ecology and numbers.

Caribou are members of a circumpolar species that has adapted to live in many different kinds of habitat, from mountains to boreal forest to the open tundra to the high Arctic. Weather they survived through the last glacial period on Haida Gwaii is a question that, in my opinion, has not been completely answered. More samples, with more dating, DNA and isotopic analysis is needed.

References

Anderson, Alexander Caulfield. 1875. Remarks on the Similarity of some Implements found in the caves of Dordogne to some used by the North American Indians, on the Germani of the Roman Period, and on the Range of the Reindeer, pp. 37-51 (letter pp. 38 -50), ref. pp.47-8. In: Reliquiae Aquitanicae; Being Contributions to The Archaeology and Palaeontology of Perigord and The Adjoining Provinces of Southern France. 1865-75, by Edouard and Henry Christy. (Ed) Thomas Rupert Jones. Williams & Norgate, London, 1875.

Banfield, Alexander William Francis. 1936. The Canadian Field-Naturalist. Vol. L No. 9. December. Ottawa.

Banfield, A.W.F. 1961. A revision of the reindeer and caribou, genus Rangifer. National Museum of Canada. Bulletin. No. 177. Biological Series No. 66.

Banfield, A.W.F. 1963 . The Disappearance of the Queen Charotte Islands’ caribou. Canada Department of Northern Affairs and National Resources. Paper No.3 and National Museum of Canda, Bulletin No. 185, Contributions to Zoology. 1962.

Barrie, J.V., Conway, K.W., Josenhans, H.J., Clague, J.J., Mathewes, R.W., and Fedje, D.W. 2005. Late Quaternary geology of Haida Gwaii and surrounding marine areas. In Haida Gwaii, human history and environment from the time of loon to the time of the Iron People. Edited by D.W. Fedje and R.W. Mathewes. University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver, B.C. pp. 7–20.

Boas, Franz. 1901. Telegram to Charles Newcombe, April 8, 1901. RBCM archives MSS 1077, Vol. 1, file 19. Victoria.

Bronk Ramsey, C. 2009. Bayesian analysis of radiocarbon dates. Radiocarbon, 51(1): 337–360.

Byun S.A., Koop B.F., and Reimchen T.E. 2002. Evolution of the Dawson caribou (Rangifer tarandus dawsoni). Canadian Journal of Zoology, 80(5): 956–960.

Byun, S. Ashley. 1998. Quaternary Biogeography of Western North America: Insights from mtDNA Phylogeography of Endemic Vertebrates

from Haida Gwaii. Ph.D. thesis, University of Victoria, Victoria.

Byun, S.A., B.F. Koop and T.E. Reimchen. 2002. Evolution of the Dawson caribou (Rangifer tarandus dawsoni). National Research Council of Canada. EBSCO Publishing.

Cannings, Robert A. and Richard Kool. (Editors) 2021. The Object’s the Thing. The Writings of York Edwards. A Pioneer of Heritage Interpretation in Canada. With foreword by Bob Peart. Royal B.C. Museum, Victoria.

Carrara P.E., Ager T.A., and Baichtal J.F. 2007. Possible refugia in the Alexander Archipelago of southeastern Alaska during the late Wisconsin glaciation. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 44(2): 229–244.

Chittenden, Newton H. 1886. Report of Exploration of Queen Charolotte Islands. December 7, 1885. British Columbia Sessional Papers.Immigration Reports. Pages 619-623. Victoria, (More comprehensive version titled: Official Report of the Exploration of the Queen Charlotte Islands for the Government of British Columbia

Clague J.J., Mathewes R.W., and Warner B.G. 1982. Late Quaternary geology of eastern Graham Island, Queen Charlotte Islands, British Columbia. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 19(9): 1786–1795.

Clague, J.J., Mathewes, R.W., and Ager, T.A. 2004. Environments of northwestern North America before the Last Glacial Maximum. In Entering America, northeast Asia and Beringia before the Last Glacial Maximum. Edited by D.B. Madsen. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, Utah. pp. 63–94.

Collison, H.A. 1905. Caribou on Graham Island. Letter to the editor. Victoria Daily Colonist. April 11:4.

Collison, H.A. 1945. The Last of the Graham Island Caribou. The Victoria Naturalist, Vol. 2, No. 4, pp. 53-57.

Cowan, Ian McTaggart.1936. Notes on Some Mammals in British Columbia Provincial Museum with a list of the Type Specimens of North American Recent Mammals in the Museum. Canadian Field Naturalist. 50:9:145-148.

Cowan, Ian McTaggart and Charles J. Guiget. 1956. The mammals of British Columbia. B.C. Provincial Museum Handbook. No. 11.

Christensen, Tina and Jim Stafford. 2005. Raised Beach Archaeology in Northern Haida Gwaii: Preliminary Results for the Coho Creek Site. In: Haida Gwaii, human history and environment from the time of loon to the time of the Iron People. Pages 245-302. University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver, B.C.

Daily Colonist. 1886. “Personal” column. November 17th, 1886.

Daily Colonist. 1908. “Vadso will Make Call at Masset”, October 22, 1908:10.

Daily Colonist. 1882. From Queen Charlotte Islands. November 10, 1882:3.

Daily Colonist. 1908. Caribou Heads Come From Graham Island. Dec. 31, 1908:2.

Daily Colonist. 1909. The Queen Charlotte Caribou. A Legend that Proved True. January 10, 1909:2.

Daily Colonist. 1919. Dates Announced for Open Hunting Seasons. July 31, 1919:10.

Dalzell, Kathleen. 1968. The Queen Charlotte Islands. Volume 1. 1774-1966. Bill Ellis Publisher, Queen Charotte City, British Columbia.

David, A., M. Latham and Stan Boutin. 2008. Evidence of Arboreal Lichen Use in Peatlands by White-tailed Deer, Odocoileus virginianus, in Northeastern Alberta. The Canadian Field Naturalist. Vol. 122, No. 3:

Dawson, George. 1878. Reports of Explorations and Surveys. 1878-9. Geological Survey of Canada. – Appendix A. On The Haida Indians of the Queen Charlotte Islands. Pages 103B.

Dawson, George. 1890. Later Physiographical Geology of the Rocky Mountain Region of Canada. Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada, Volume VIII, Section IV:51-52.

Douglas, James. 1861. Letter of September 16. British Parliamentary Papers – Canadian Affairs, B.C. vol. 39. Imperial Blue Books on Affairs Relating to Canada. Reports, Returns and other Papers. (See British Columbia Archives, NW971 G786)

EDWARDS, R. Y. 1954. Fire and the decline of a mountain caribou herd. Journal of Wildlife Management. 18(4):521-526.

Edwards, R.Y. 1956. Snow depths and ungulate abundance in the mountains of Western Canada. J. Wildlife Manage. 20(2):159“168

Edwards, R. Y. AND R. W. RITCEY. 1959. Migrations of caribou in a mountainous area in Wells Gray Park, British Columbia. Can. Field Nat. 73(0:21-25.

Edwards, R. Y. AND R. W. RITCEY. 1960. Foods of caribou in Wells Gray Park, British Columbia. Canadian Field Naturalist 74(1):3~7.

Edwards, R.V. and J. S00S, AND R. V/. RITCEY. I960. Quantitative observations of epidendric lichens used as food by caribou. Ecol. 41(3):425-431.

Fannin, John 1892. The Deer of British Columbia. Victoria Daily Colonist. January 1, 1892:5.

Fedje D.W. and Josenhans H. 2000. Drowned forests and archaeology on the continental shelf of British Columbia. Geology, 28: 99–102.

Fedje, Daryl, Quentin Mackie, Duncan McLaren, Becky Wigen, John Southon. 2021. Karst caves in Haida Gwaii: Archaeology and paleontology at the Pleistocene-Holocene transition. Quaternary Science Reviews. 272. 107221.

Fedje, D.W., and Mathewes, R.W. 2005. Conclusion: Synthesis of Environmental and Archaeological Data. In: Haida Gwaii, human history and environment from the time of loon to the time of the Iron People. Pages 372-375. University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver, B.C.

Fedje, D., and Smith, N. 2010. Gwaii Haanas archaeology and paleoecology. Report on file (2009-10 unpublished), Parks Canada, Ottawa, Ont.

Florent Rivals, Matthew C. Mihlbacher; Nikos Solounias; Dick Mol; Gina M. Semprebon; John de vos; Daniela C. Kalthoff. 2010. Palaeoecology of the Mammoth Steppe fauna from the late Pleistocene of the North Sea and Alaska: Separating species preferences from geographic influence in paleoecological dental wear analysis. Palaeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 286:42-54.

Foster, J.B. 1965. The evolution of the mammals of the Queen Charlotte Islands, British Columbia Provincial Museum Occasional Paper No. 14:1-130, Victoria, B.C.

Fox C.H., Paquet P.C., and Reimchen T.E. 2018. Pacific herring spawn events influence nearshore subtidal and intertidal species. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 595: 157–169.

Galois, Robert. 2004. A Voyage to the North West Side of America: The Journals of James Colnett, 1786-89. UBC Press. Vancouver, B.C.

Guiguet, Charles. 1972. Letter to the Queen Charlotte Island Museum Society. October 22, 1972. In: The Charlottes. A Journal of the Queen Charlotte Islands. The Land and the People – Yesterday and Today. Published by The Queen Charlote Islands Museum Society. Volume 3:44.

Gibbs, George. 1854. Report of Mr. George Gibbs to Captain McClellan, on the Indian Tribes of the Territory of Washington. Olympia, Washington Territory, March 4, 1854. In: Reports of Explorations and Surveys, to Ascertain the Most Practical and Economical Route for a Railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean, Made Under the Direction of the Secretary of War, in 1853-4, According to Acts of Congress of March 3, 1853, and August 5, 1854. 33rd Congress, 2nd Session, Senate Executive Document No. 91, (Serial No. 758) Washington, Beverly Tucker, Printer. (Reprinted by Ye Galleon Press, Fairfield, Washington, 1967).

Ham, Lenard C. 1990. The Cohoe Creek site: a late Moresby Tradition shell midden. Canadian Journal of Archaeology. 14: 199–221.

Heaton T.H., Talbot S.L., and Shields G.F. 1996. An ice age refugium for large mammals in the Alexander Archipelago, southeastern Alaska. Quaternary Research, 46: 186–192.

Hebda R.J, Lian O.B., and Hicock S.R. 2016. Olympia Interstadial: vegetation, landscape history, and paleoclimatic implications of a mid-Wisconsinan (MIS3) nonglacial sequence from southwest British Columbia, Canada. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 53 (3): 304–320.

Heusser, C.J. 1989. North Pacific coastal refugia — The Queen Charlotte Islands in perspective. In The outer shores. Edited by G.G.E. Scudder and N. Gessler. University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver, B.C. pp. 91–106.

Hunt Commander and Lieutenant Bills. 1906, The Caribou of Queen Charolette Islands. Ottawa Naturalist20;73-76..

Josenhans, H.W., Barrie, J.V., Conway, K.W., Patterson, T., Mathewes, R., and Woodsworth, G.J. 1993. Surficial geology of

the Queen Charlotte Basin: evidence of submerged proglacial lakes at 170 m on the continental shelf of western Geol. Survey

Canada Curr. Res. Papers. No. 93–1A. pp. 119–127.

Jacobsen, Adrian. 1977. Alaskan Voyage, 1881-1883. An Expedition to the Northwest Coast of America. Translated by Erna Gunther from the German Text of Adrian Woldt (1884). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Keen, Reverend J. H. 1906. Letter to Charles Newcombe. April 20, 1906.RBCM Archives MSS 1077, Vol. 4, file 89. Victoria.

Kermode, Frank. 1906. Letter of March 6, 1906 to Charles Newcombe. RBCM archives Ad. MSS 1077 Vol. 4, file 89. Victoria.

Kubiak, Cara; Rolf Mathews; Vaughan Grimes, Geert Biesen and Micheal Richards. 2021. Evidence of a significant marine plant diet in a Pleistocene caribou from Haida Gwaii, British Columbia, through compound-specific stable isotope analysis. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. Vol. 564. 15 Feb.,110180.

Lathem, David A. and Stan Boutis. 2008. Evidence of Arboreal Lichen Use in Peatlands by White-tailed Deer, Odocoileus virginianus, in Northeastern Alberta. Canadian Field-Naturalist 122(3): 230-233.

Lacourse T., Mathewes R.W., and Fedje D.W. 2003. Paleoecology of late-glacial terrestrial deposits with in situ conifers from the submerged continental shelf of western Canada. Quaternary Research, 60: 180–188.