Preface

“Carcass butchery is a culturally mediated behavior that reflects the technological, social, economic and ecological factors that influence human diet and foodways. Butchery behavior can thus reveal a great deal about the lives of past peoples” (Egeland et. al. 2024).

Egeland. et.al., examined 236 studies on butchery, published between 1860 and 2021, to observe trends. This involved both studies that involved the reconstruction of ethological knowledge and archaeological evidence. The majority of these were undertaken on large bovids. The authors were interested in making recommendations for future studies. They note that one should look for evidence such as: “cut mark frequences on carcasses of different body sizes and taxon”. Part of this study looked at factors such as what kind of tools were used and what kind of experience the person(s) doing the butchering had.

When it comes to studying archaeological remains, I would emphasize the importance of the nature of the material and its context being studied. In my study of marmot butchering, I was able to come to both specific and broader conclusions about human behavior because of the unique preservation of large bone samples, in cool rock shelter environments, that served limited hunting activities. I was able to determine that, at least, among some Nuu-chah-nulth families, marmots were only partially processed in mountain alpine environments where they were captured.

Marmots were skinned, their heads and legs discarded in the rock shelter. Subsequently, the upper body with ribs and vertebrae, holding most of the fat, were carried back to their coastal villages (Keddie 2023; Nagorsen, Keddie & Luszcz 1996). I would speculate that the latter were carried back inside the skins and the skins were treated back at the village. This kind of study would be difficult to do with only the very scattered occurrence of bones in coastal shell middens. The original context of the bones in the midden may have changed due to a range of factors such as soil acidity, activity of dogs, cleaning and construction projects.

My Exploratory Study

I was curious as to how Sea lions, with their very thick skin, may have been processed by Indigenous people on the coast of British Columbia. Indigenous knowledge about what kind of stone tools had been used in the past had long disappeared. Iron tools were rapidly replacing stone tools in the late 18th century and it would appear that this had begun even earlier (Keddie 2006).

In some cases, even with the use of steel knives, cultural obligations of the specific ways in which a carcass would be cut up and distributed may have been passed on by those populations, who continued to hunt sea lions into the mid 19th century. However, I would suggest that the specific parts of the carcass eaten likely changed over time with changes in social obligations and the adoption of new food resources.

I had two opportunities in 1979, to experiment on dead sea lions. In both cases these were ones that had been shot in the head and washed up on beaches in greater Victoria, on southern Vancouver Island.

In a perfect study, what I would prefer was having the time to butcher a sea lion carcass with stone tools into the portions known to be removed, as recorded by Indigenous peoples in earlier times. I would then study the cut marks I made with these tools and compare them with cut marks on ancient sea lion bones. I did not have time in the two cases mentioned here, as the dead sealions were seen as a health hazard in urban areas and the prime purpose of recovering them was to obtain the skeletons for the Royal B.C. Museum comparative collection. However, my exploratory efforts shown here might contribute in a small way to future studies. For future studies I have included as Appendix 2, the excellent notes of Charles Newcombe on how sea lions were killed and at what age and sex.

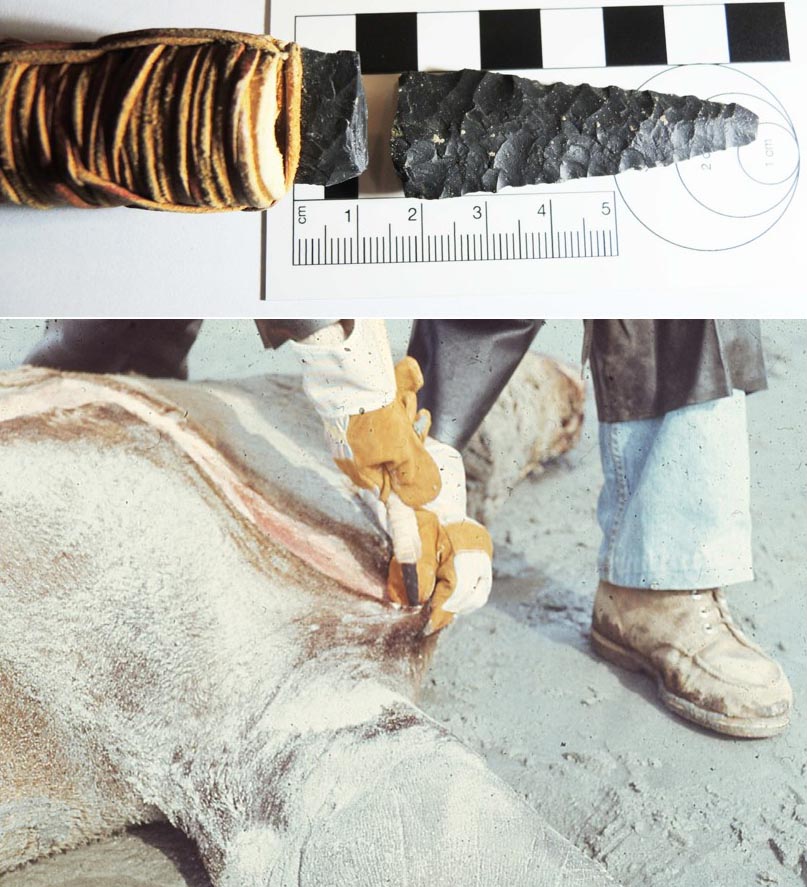

Figure 2, shows the bifacial dacite knife blade the author made, being used to skin a sea lion. It later broke when too much lateral torgue was used.

My Butchering Experience

As a child my older brother George and I snared and skinned snowshoe hairs around Edmonton Alberta. These were sold to a furrier. We received one dollar and 25 cents for the skin and 20 cents for the cut off feet. The feet were encircled with a copper band around the top attached to a small clip together chain These were sold in stores as “Lucky rabbit feet”.

We were given instructions as to how they needed to be cut and scrapped. At this time, we used sharp steel knives and razor blades for finer cuts. With snowshoe hairs, much of the skinning involved simply pulling the skin off.

I also butchered many fish I had caught in my youth at Skeleton Lake, Alberta, were I spent many summer weekends up to the age of 13. My later interest in ancient human cultures sparked me into experimenting to see how butchering might be done with stone tools. I used what we called cobble coppers, to chop off legs of road kill deer and stone flakes to partially skin them. I learned that the effort one had to put into skinning, changed with the thickness of the animal skin.

What was used from the carcass?

The ethnographic information on the details of sea lion butchering on the southern coast of British Columbia is very sparse. In the regions, where it did exist over the millennium, it likely changed in both extent and details of processing. The extensiveness of the butchering process in the more distant past may be reflected in the known historic process. This is best documented for the Aleut peoples of Alaska, where almost every body part was used and their use was known. I have provided some detail of the latter in Appendix 1, “Butchering Everything”, as food for thought for future British Columbia studies. It includes an interesting first hand, up close, observation of an Aleut woman, as she completely dismantles a sea lion carcass with specific parts for a number of uses beyond just eating them. The biologist, Henry Elliott, in 1873, observed her do this and pack it all away, with only the assistance of a young boy, in just one hour.

In coastal British Columbia, traditional bow strings were made from long sea lion tendons. Although, often referred to in the literature as sinew or gut, the best material would be the backbone tendons of sea lions. Tendons have the joining function between your muscles and bones. They are made up of fibres that run parallel to each other, providing support and elasticity to body movements. Tendons bind muscle to bone. Ligaments that bind bone to bone are usually shorter and lack the important longer parallel feature. The term sinew refers to tough fibrous tissue. This includes both tendons and ligaments. Either type of sinew would have been used to tie arrow and spear shafts and to sew together items such as clothing and bags. A “gut” is the gastrointestinal system and includes your stomach, intestines and colon. It is often difficult to tell in the literature which kind of tissue is being referred to.

Anthropologist, Homer Barnett noted: “Plant fibers were seldom made into bow strings. More common were two-ply cords of sinew and gut” (Barnett 1955). This was mentioned by Anthropologist Dave Rozen who referred to “sea-lion gut or sinew” as “I tl’imen” in the Hul’qumi’num language. The name was interpreted as ‘muscle, cord’ (Rozen 1978:237). There is often confusion in interpreting words such as gut, sinew, ligament, tendon and muscle. I would suggest that the term ‘muscle, cord’ here would refer to the longer tendons.

The name information was provided by two Cowichan brothers, Abraham Joe (February 15, 1905 – September 28. 1986); [His father was Joseph Joe, his mother Cecelai Martin, his wife Loraine Reuben and son Harold Joe. His grandparents were Joe Smaquaset and Julia Schulseemum of the Somanos reserve], and Abel Dominic Joe (August 17, 1914 – June 30, 1989 ). [His wife Lana James]. A third person that confirmed the name was Christopher Paul of the Tsartlip Reserve.

Anthropologist Franz Boas describes, in detail, the making of wedge carrying bags from sea lion hides among the Kwakiutl (Boas 1921). There is no information on details of sea lion processing, but it is likely a similar process happened as with seals. The bladders of sea lions were likely carefully taken out, blown up and dried, as containers for storing their rendered oil. Swan noted, in 1857, the processing of seals among the people of Shoal Bay Washington:

“The blubber is next cut off in strips, which are boiled in water, and the oil skimmed off with shells. After it has settled and cooled, it is poured into a bottle (as they call it), made of the paunch of the animal blown up like a bladder and dried. In every lodge may be seen these bladder-like bottles, and the more an Indian has the greater his wealth” (Swan 1992).

.As with seals, we can surmise that sea lion upper body parts containing fat and meat was steamed in a pit and preserved by drying. Given their size it is likely that sea lions would be processed on the beach and a lot of material left behind.

The Weir’s Beach Sea Lion

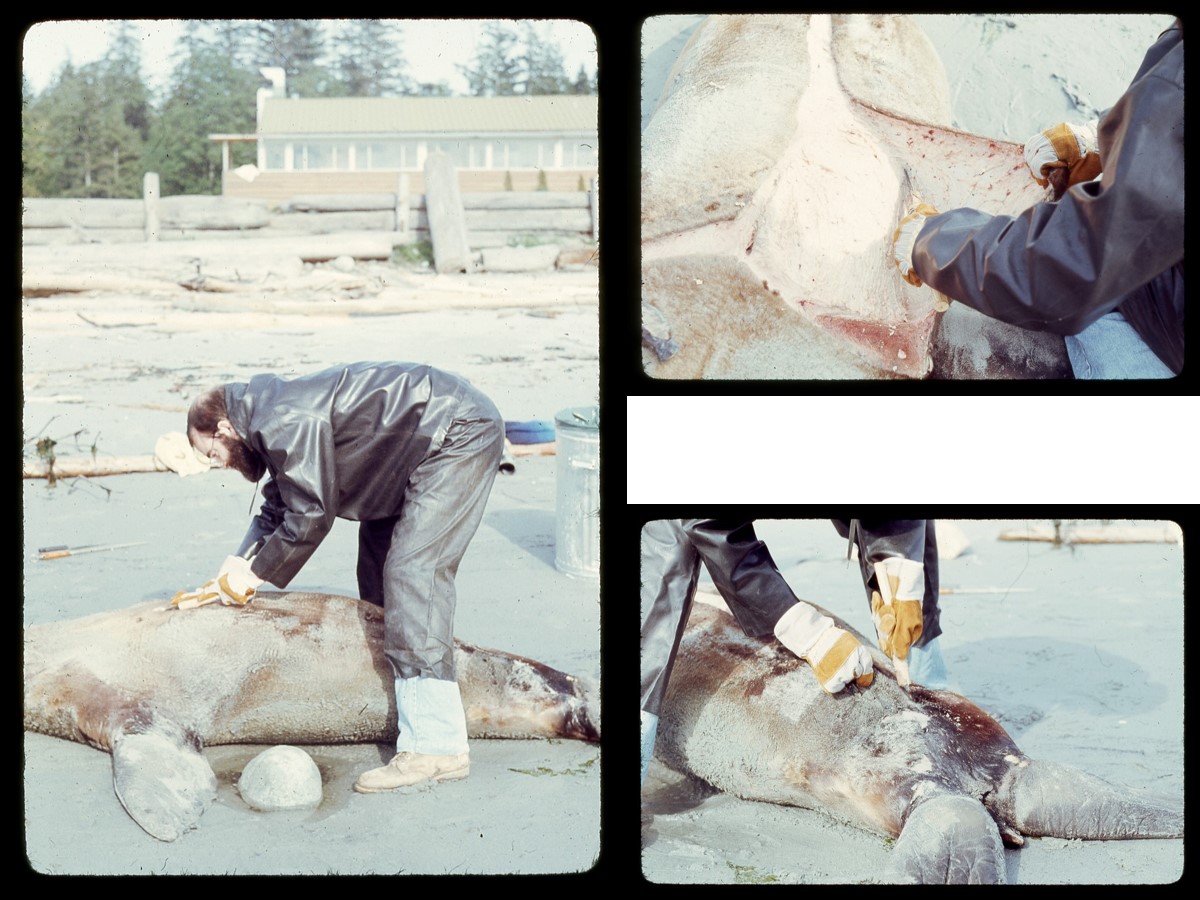

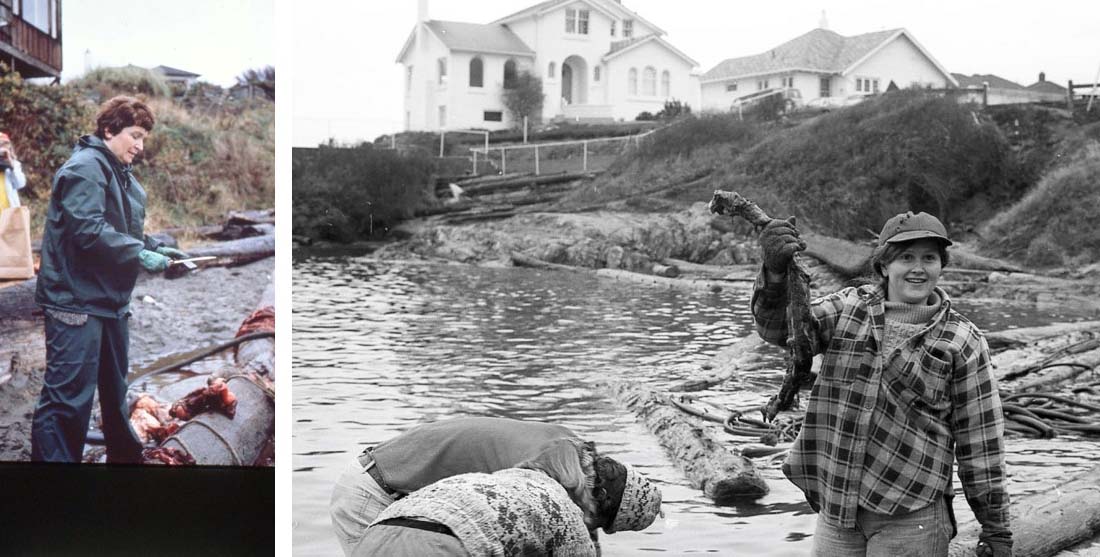

On May 11, 1979, I went with Susan Crockford, then my college at the Royal B.C. Museum, and Rebeca Wigen of the University of Victoria, with the objective of butchering a dead sea lion washed up on Weir’s Beach in Metchosin. This was for getting the skeleton for the Royal B.C. Museum comparative collection, which Susan had played an important part in developing. Figure 3, shows two of the tools I took with me. I flaked a thin knife point of dacite which was similar to ones that had worked for me when skinning deer (Figure 2). In figure 4, the author is shown skinning the Weir’s Beach sea lion with this knife.

I was also curious to see if a sharp-edged slate knife would work. I had used ulu shaped slate knives successfully for butchering fish, so I thought this longer, more elongate knife shaped example might work. It turned out that this tool did not work as well except on soft flesh, and it would have been necessary to frequently sharpen it. Flaked stone tools were more efficient at cutting. Similar ground slate artifacts I had observed in collections were more likely used as spear points for killing and not used in butchering.

One of the important aspects of team work was the pulling of the skin tight to facilitate easier cutting as shown in figures 4, 5 and 6. Figure 6, shows the use of a bifacial obsidian knife that worked well for the hard to get at areas near the flippers.

Figure 7, on the left, shows the author using the experimental slate knife, seen in figure 3, to cut flesh away from the skin. On the right is the author using the dacite stone bladed knife to cut muscles attached to the flipper.

Figure 8, shows the broken dacite knife blade. It snapped off when using too much lateral torque cutting tough ligaments.

What worked best for skinning was the stone point I made and fitted into a 24cm long hard wood handle with a circumference of 2cm (Figure 2 and 8). I was interested in seeing how small of a point could be used for skinning without breaking. The flaked point was a 9.2cm long, dacite biface, with 6.7cm exposed above the haft. It was 2cm wide and 0.5cm thick (Figure 8 ).

Figure 2, shows me cutting the hide with my flaked stone knife. The tool worked very well to skin the hide but later snapped off due to too much lateral torque. Other obsidian bifaces and blades were then used, and further butchering was completed with steel knives. What worked most effectively was a team effort when Susan pulled the skin tight while I cut it (Figure 6 and 7 ).

The Ross Bay Beach Sea Lion

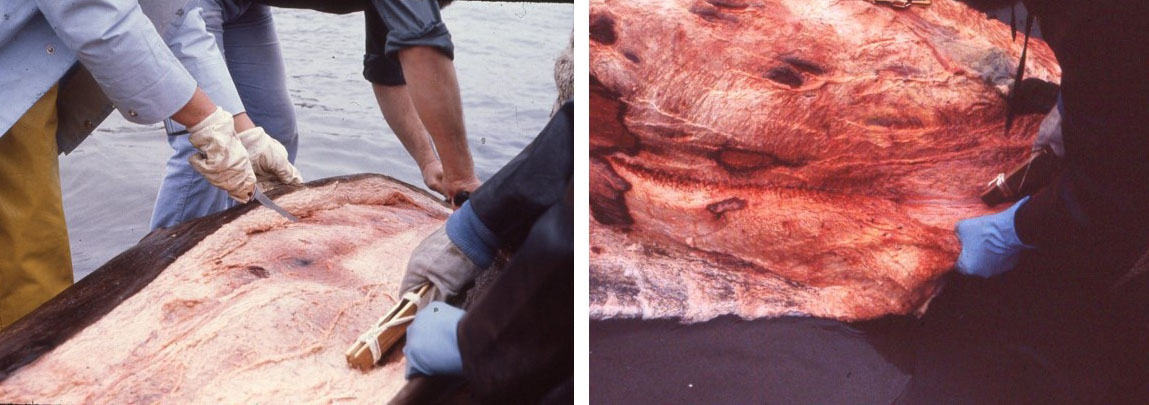

A second opportunity to butcher a sea lion happened on Dec. 3, 1979, when one washed up at the east end of Ross Bay, Victoria. A team of people from the Archaeology Division of the Royal B.C. Museum, included Susan Crockford, Gay Frederick, Jim Haggarty, Cathy Carlson, Ross Brand and Nancy Romaine. We are shown pulling the dead sea lion to shore (Figure 9).

For this event, I made an assemblage of tools from large side hafted obsidian blades, dacite flakes and a few small hafted microblade tools (figure10). The larger hafted blade tool seen here was harder to wield than the medium sized one, which allowed a more powerful grip.

Figure 11, shows Gay Frederick, Jim Haggarty and Cathy Carlson starting the skinning of the carcass with steel knives.

Figure 11. Removing the sea lion skin with steel knives.

In figure 12, I am shown cutting tendons, ligaments and muscle with different tools, which included an obsidian blade in a medium sized wooden haft and a small hafted microblade

Figure 14, on the left, shows both a steel knife and obsidian hafted blade being used to cut similar flesh. The obsidian blades worked well but the steel blades worked better and longer. I practiced using the microblade tools to cut through small but hard tendons and ligaments. This worked surprisingly well.

Figure 15 shows Gay Frederick, Jim Haggarty, Susan Crockford and Cathy Carlson swiftly cutting with steel knives, as I try to keep ahead of them with my experimental cutting.

Figure 16, shows Nancy Romain sharpening the steel knives on the left and Susan Crockford on the right, getting the first rib clear.

The Indigenous Background

In many coastal hunter-fisher-gatherer populations, where fishing was a predominant activity, there were individual families that were known to be focused on inland mammal resources. There were also some populations where some families were more focused on hunting sea mammals. The latter people would have specialized knowledge of how sea lions were butchered.

The hunting of sea lions was wide spread from Siberia to South America. Large scale seasonal hunts were organized with Indigenous peoples in the Santa Barbara region of California (Lyman 1989; 1995), but only the co-operative hunt of the Penelakut on the east coast of southern Vancouver Island, was known for southern British Columbia. This co-operative hunt was not the usual method for hunting sea lions along the coast of British Columbia.

Anthropologist. Wayne Suttles. was told that anyone could hunt seals or porpoise without having any special rituals. He noted: “All the informants whom I questioned on the mater said that the only sea-mammal hunters who engaged in any ritualism were Penelekuts sea-lion hunters. The Penelekuts and only they regularly hunted sea-lion; Penelekuts sea-lion hunters fasted and remained celibate before going out, used spells and songs to calm the animals, and divided the carcass among members of a hunting party according to fixed rules. The Straits people did not share these practices.” (Suttles 1974).

Information on sea lion hunting by Hul’qumi’num speakers on the east coast of Vancouver Island comes largely from a single Penelakut person, Leo Mitchell (c. 1874 – July 14, 1955). Mitchell’s knowledge was collected by Suttles, during his field work from 1949 – 1950. Leo Mitchell, from Kuper Island, was listed on his death certificate, at age 81, as a “Sheep farmer and fisherman”.

Suttles recorded: ”Hunting sea lions was a dangerous pursuit which required special knowledge and probably special spirit power. John Peter one of the last Penelekut harpooners, had a ‘black fish’ (killer whale) guardian spirit” … “The sea lion carcass was divided according to a formula following the order of striking. The first man to strike the animal received the rear portion and the head. The second got one flipper, the third the other flipper, the fourth the back, the fifth the neck, and the rest got pieces of the belly. Each harpoon then divided his share with his paddler. Everyone got a piece of the gut, which was, stretched, twisted, and dried for cord. The Penelekuts provided their neighbours to the south with sea-lion gut cord for bow strings” (Suttles 1987). John Peter (c.1846 – September 6, 1946), lived on the North Galiano Reserve No. 9,

Fixed rules about carcass division can be found farther south in California. Anthropologist Alfred Kroeber notes that among the Yurok of California “prestige rights like that to sea lion flippers or shoulder strips were particular claims of particular families (houses), not characterising any village or district headman”. In regard to the Twana, Elmendorf notes that there was no individually received spirit power for sea-lion hunting and the hunting had no special relation to wealth: “Although the privilege of claiming the flippers, or a side-of-neck strip of all sea lions killed in certain stretches of coast carried high prestige. It was an inheritance of honour rather than of wealth” (Elmendorf 1960).

Discussion

Changes in the Past

There have been engaged discussions in the past regarding the importance of the role of sea mammal hunting among cultures along the north Pacific coast (Lyman 1995; Jones and Hildebrandt 1995; Colten and Arnold 1998; Porcasi and Jones 2000; Kennett and Kennett 2000).

As Colten and Arnold point out, they see “evidence of local and regional difference rooted in variable, cultural settings, physiographic and oceanographic conditions, and available technologies”. They consider weather the observed patterns in some regions of California can be applicable generally to more distant regions of the Pacific coast (Colten and Arnold 1998).

We do not have sufficient data on sea lion remains from archaeological sites in British Columbia to examine the story of Indigenous hunting and processing on either a regional or wider coastal perspective. The best effort in this direction is the publication by Iain McKechnie and Rebecca Widen (2011). Much further work is needed to examine regional patterns. This will involve large scale DNA and isotopic studies to compare bone samples up and down the coast and through time.

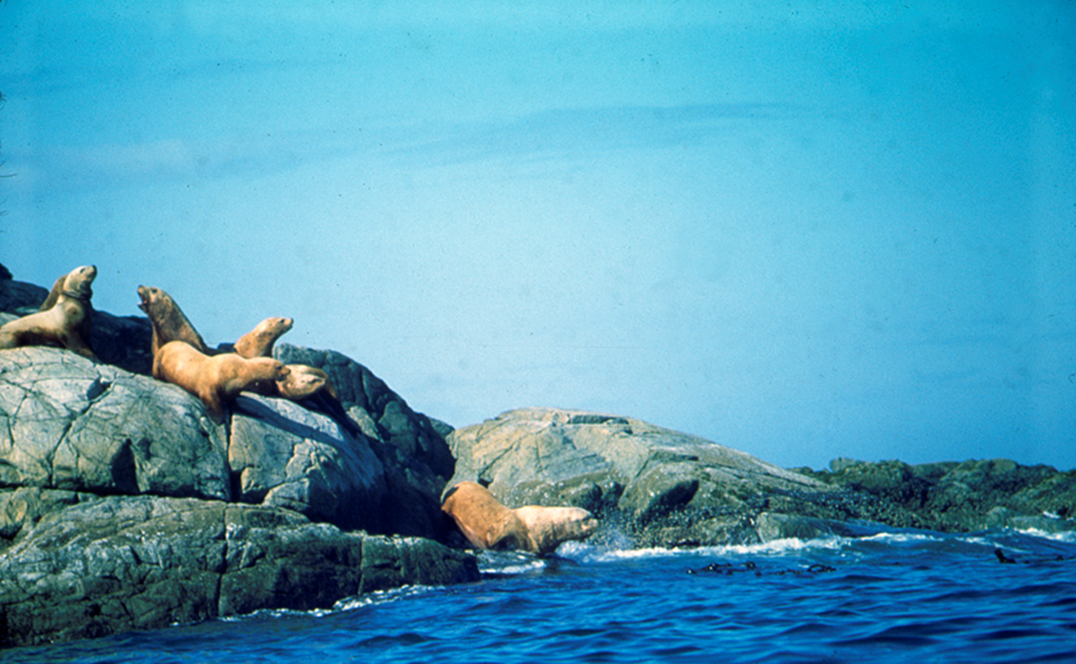

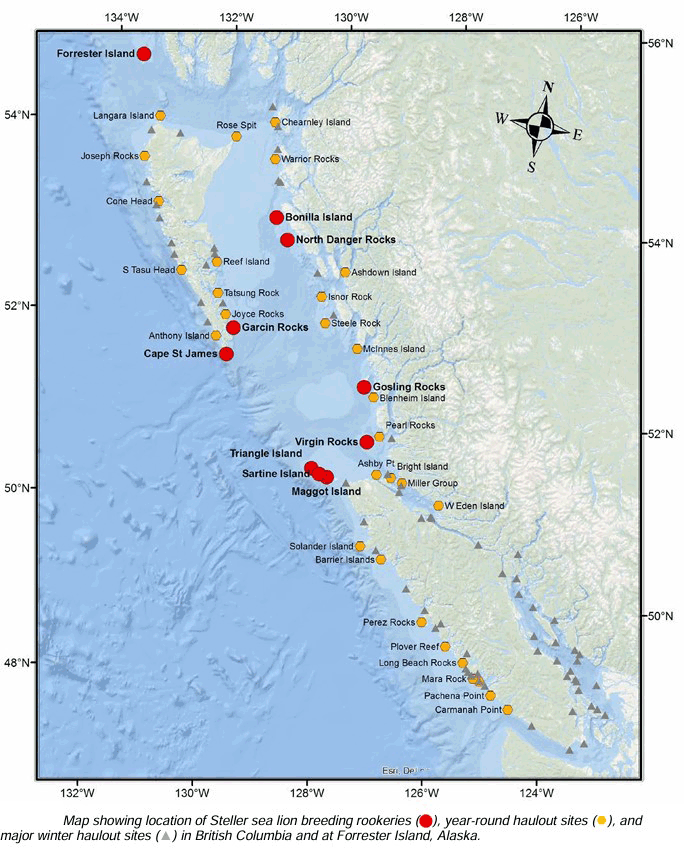

Steller sea lions (Eumetopias jubatus), were the most common species on the southern coast of British Columbia, some are around all year, but most are only seasonally present in the winter and spring. At least in historic times they did not have rookeries on the southern coast, but this may have been different in the past. The closest rookeries today are on the Scott Islands off the northwestern tip of Vancouver Island. California sea lions (Zalophus californianus) are present in fewer but increasing numbers. Small numbers of elephant seals (Mirounga angustirostris) migrate to the southern B. C. coast seasonally.

The map shown here as Figure 17, is from Peter Olesiuk’s 2018, publication: Recent Trends in Abundance of Steller Sea Lions. It shows the breeding rookeries in red circles, the year round haul out sites in orange circles and the major winter haul out sites as black triangles. When I look at this, I wonder why there are no rookeries on the southern portions of the map. Future zooarchaeology studies will determine if there were many more rookeries in the past.

The Changing Settings

In the past, sea level changes would be expected to eliminate or reduce small island rookeries and haul outs, but also create locations for new rookeries and haul outs. This may not result in drastic changes for sea lion populations on a larger regional basis. What would make a difference are periotic changes in sea temperature brought on by the effects of El Niño and La Niño events. It has been established from modern studies, that warmer sea temperatures have a negative effect on sea mammal populations. How much this has to do with decreases in fish populations, shifts in human settlement patterns and resource intensification needs to be demonstrated in the future.

Were there far more rookeries in the past? Anthropologist Roberta Hall, analysed 1420 sea mammal specimens from the Nah-so-mah village (35-CS-48) on the estuary of the Colquille River, in Oregon. Sea lion bones made up 35% of the assemblage. It included both Steller and California sea lions, but more of the former. The age range was 23% adult, 14% juvenile and infant 13%. The fact that there are infants in the assemblage, and there are no sea lion rookeries near the Colquille River region, suggests that there must have been one in the past. Most bone types were represented in the sample and “Cut marks or striations apparently made by sharp stone tools”, were noted of 54 sea lion bones (Hall 2001).

The types of sea mammals that were focused on in the past may have varied considerably. One example of sea mammal specialization is found at the Ozette site on the Olympic Peninsula of Washington State. Here, sea mammals, excluding whales, represented 95% of all mammals, with 90% being fur seals. Sea lions and porpoise made up small numbers (Huelsbeck 1994; 1998).

What bones end up in archaeological sites, in part depends on where the carcass is processed. The latter depends on how far the carcass, or parts, need to be transported and how big the sea lion is. Steller’s sea lion males can be 1200 – 1500 lbs or more. As sea lions can be dangerous, it is likely that a focus of attention was killing the younger ones (see Newcombe and Newcombe 1914; Newcombe, Greenwood, and Fraser. 1918.). The latter would also be easier to load into canoes. The size of the canoes used in transport would be important. In the Santa Barbara region of California, it was the practice to tip a canoe partly on its side and pushing the sea lion with water inside, righting it, and then bailing out the water.

As Suttles noted, the Penelekut from the Ladysmith region, hunted sea-lions cooperatively (Suttles 1987), but there is no recorded documentation on who butchered them. As the Porlier Pass area was the main hunting region, the sites in this location may be the best to reveal what tools were used in the butchering process. Can we identify sites whose primary deposition was a result of hunting sea lions?

Steller sea lions, as expected, were the most prevalent species found in archaeological sites on the southern coast of B.C. It is of interest, however, to see the very low levels of ancient hunting of California sea lions (McKechnie and Wigen 2011). This may be explained by a more expanded recent movement of larger numbers of California sea lions northward to Vancouver Island. Biologist, Charlie Guiguet, noted the recent increase in the establishment of California sea lions on southern Vancouver Island was due to the protective laws in California which greatly increased the population (Guiguet 1971) .

What tools were being used to butcher sea lions.

Throughout most of the Indigenous history of British Columbia, stone tools were used to butcher mammals. What I found in the use of cutting tools was the importance of knowing the level of toughness of internal ligaments, tendons and muscles. Could these different structures require different kinds of tools to be more effective in cutting? Cutting of internal body parts does not necessarily result in producing cut marks on bones that would contribute to our understanding of butchering techniques. See Appendix I for the many internal organs this may have involve at various times in the past. Different tools were likely used on softer material from the same animal. Cutting tough ligaments and tendons or stripping gut can best be done with a very small sharp stone tool.

Factors I see that are important, include experience of the butcher; skin thickness; and the use of hafted or un-hafted tools. Much more strength is needed for a hand-held cutting tool. Most tools for cutting sea lions were likely hafted. The shorter of the two hafted large bladed tools I used worked best. It was harder to manipulate the largest hafted tool that I used.

One interesting and important fact, is that we do not find evidence of the large sharp edged cutting blades, that I have found work well for butchering. These are rarely found in archaeological sites on the southern British Columbia coast. Larger bifaces with a serrated edges work well, but these are uncommon in sites dating to the last 1500 years. Thinner bifaces cut more efficiently. The thin flakes we find in archaeological sites with fine retouched edges seem to be the best candidates for artifacts used for much of the butchering. These were likely hafted for larger animals, such as sea lion.

Fine grained sharp stone blades used as knife blades work well. They do dull after use, but can be used again several times by creating and re-creating finely flaked edges.

I have used microblades extensively on many plant and animal materials where they have worked efficiently. They are particularly useful for cutting specific tendons and ligaments and sectioning out delicate internal organs. These have been found hafted in the Hoko River site on the Olympic Peninsula of Washington State (Flenniken 1980). My own examination of microblade edges show they were hafted both on the side and from their proximal ends. However, microblades have not been used in, at least, the last 1500 years on the southern coast. Iron tool blades were common in some cultures in S.E. Alaska 1200 years ago. Maybe that was also the case in British Columbia where preservation of iron was not as good as in Alaska.

Appendix I

Butchering Everything

Biologist Henry Elliot was measuring and drawing a sketch of a freshly killed adult bull sea lion, when an elderly Aleut woman:

“came up abruptly; not seeming to see me, she deliberately threw down a large, greasy, skin meat-bag, and whipping out a knife, went to work on my specimen. Curiosity prompted me to keep still, in spite of the first sensations of annoyance, so that I might watch her choice and use of the animal’s carcass.

She first removed the skin, being actively aided in this operation by an uncouth boy; she then cut off the palms to both fore flippers; the boy at the same time pulled out its mustache-bristles; she then cut out its gullet, from the glottis to its junction with the stomach, carefully divested it of all fleshy attachments and fat; she then cut out the stomach itself, and turned it inside out, carelessly scraping its gastric walls free of copious biliary secretions, the inevitable bunch of ascaris; she then told the boy to take hold of the duodenum end of the small intestine, and, as he walked away with it, she rapidly cleared it of its attachments, so that it was thus uncoiled to its full length of at least sixty feet; then she severed it and then it was re-coiled by the “melchiska,” and laid up with the other members just removed, except the skin, which she had nothing more to do with.

She then cut out the liver and ate several large pieces of that workhouse of the blood before dropping it into her meat-pouch. She then raked up several handfuls of the “leaf-lard,” or hard, white fat that is found in moderate quantity around the viscera of all these pinnipeds, which she also dumped into the flesh-bag; she then drew her knife through the large heart, but did not touch it otherwise, looking at it intently, however, as it still quivered in unison with the warm flesh of the whole carcass.

She and the boy then poked their fingers into the tumid lobes of the immense lungs, cutting out portions of them only, which were also put into the grimy pouch aforesaid; then she secured the gall-bladder and slipped it into a small yeast-powder tin, which was produced by the urchin; then she finished her economical dissection by cutting the sinews out of its back in unbroken bulk from the cervical vertebra to the sacrum ; all these were stuffed into that skin bag, which she threw on her back and supported it by a band over her head; she then trudged back to the barrabkie from whence she sallied a short hour ago, like an old vulture to the slaughter.

She made the following disposition of its contents: The palms were used to sole a pair of tarbosars, or native boots, of which the uppers and knee-tops were made of the gullets-one sea-lion gullet to each boot-top; the stomach was carefully blown up and left to dry on the barrabkie roof, eventually to be filled with oil rendered from sea-lion or fur-seal blubber.

The small intestine was carefully injected with water and cleansed, then distended with air, and pegged out between two stakes, sixty feet apart, with little cross-slats here and there between to keep it clear of the ground. When it is thoroughly dry it is ripped up in a straight line with its length and pressed out into a broad band of parchment gut, which she cuts up and uses in making a water-proof “kamlayka,” sewing it with those sinews taken from the back.

The liver, leaf lard, and lobes of the lungs were eaten without further cooking, and the little gall-bag was for some use in poulticing a scrofulous sore. The mustache- bristles were a venture of the boy, who gathers all that he can, then sends them to San Francisco, where they find a ready sale to the Chinese, who pay about one cent apiece for them. When the natives cut up a sea-lion carcass, or one of a fur-seal, on the killing-grounds for meat, they take only the hams and the loins. Later in the season they eat the entire carcass, which they hang up by its hind flippers on a “laabas” by their houses”.

Additional information on the above is noted in other contexts by Elliott:

“Although the sea-lion has little or no commercial value for us, yet to the service of the natives themselves, who live all along the Bering Sea coast of Alaska, Kamchatka, and the Kuriles, it is in-valuable; they set great store by it. It supplies them with its hide, mustaches, flesh, fat, sinews, and intestines, which they make up into as many necessary garments, food-dishes, etc. They have abundant reason to treasure its skin highly, since it is the covering to their neat bidarkas and bidarrahs, the former being the small kayak of Bering Sea, while the latter is a boat of all work, exploration and transportation. These skins are unhaired by sweating in a pile, then they are deftly sewed and carefully stretched over a light keel and frame of wood, making a perfectly water-tight boat that will stand, uninjured, the softening influence of water for a day or two at a time, if properly air-dried and oiled. After being used during the day these skin boats are always drawn out on the beach, turned bottom-side up and air-dried during the night-in this way made. ready for employment again on the morrow.

A peculiar value is attached to the intestines of the sea-lion, which, after skinning, are distended with air and allowed to dry in that shape; then they are cut into ribbons and sewed strongly together into that most characteristic rain-proof garment of the world, known as the “kamlayka,” which, while being fully as water-repellant as India-rubber, has far greater strength, and is never affected by grease and oil. It is also transparent in its fitting over dark clothes. The sea-lions’ throats are treated in a similar manner, and when cured, are made into boot tops, which are in turn soled by very tough skin that composes the palms of this animal’s fore flippers.

Around the natives’ houses, on St. Paul and St. George, constantly appear curious objects which, to an unaccustomed eye, resemble overgrown gourds or enormous calabashes with attenuated necks; examination proves them to be the dried, distended stomach-walls of a sea-lion, filled with its oil-which (unlike the offensive blubber of the fur-seal) boils out clear and inodorous from its fat. The flesh of an old sea-lion, while not very palatable, is tasteless and dry; but the meat of a yearling is very much like veal, and when properly cooked I think it is just as good; but the superiority of sea-lion meat over that of the fur-seal is decidedly marked.”

The tough, elastic mustache-bristles of a sea-lion are objects of great commercial activity by the Chinese, who prize them highly as pickers for their opium pipes, and several ceremonies peculiar to their joss-houses. Such lip-bristles of the fur-seal are usually too small and too elastic for this service. The natives, however, always carefully pluck them out of the Eumetopias, and get their full value in exchange”.

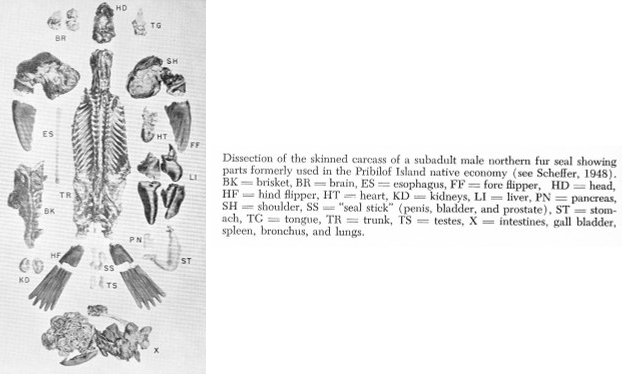

The Visual Parts of a Carcass

A visualization of the parts removed by the Aleut woman with a few differences was produced by Biologist Victor Scheffer in regard to the Fur seal (not the sea lion) in his 1958 publication. He had extracted this (my figure 18) from his 1948 publication on the: Use of fur seal carcasses by Natives of the Pribilov Island.

Grant Keddie Additional Note to Appendix I.

The Aleut intestine parkas mentioned in the Appendix 1, were being used on the lower Columbia River at Fort George in 1817. These parkas were likely acquired from the Russians at Fort Ross which was established by the Russian-American Fur Company in 1812.

The reference to these was made by fur trader, Ross Cox while working for the John Jacob Aster Company. Cox noted:

“the only protection for those whose duty compels them to be in the open air, is a shirt made from the intestines of sea lion, the parts of which are ingeniously sewed together with fine threads of nerf. A kind of capuchin, or hood, is attached to the collar: and when this garde-pluie is on, the wearer may bid defiance to the heaviest rain. These shirts are made by the natives in the vicinity of the Russian settlements to the northward of the Columbia and some of them are neatly ornamented.”

Appendix 2.

Notes on Sea-lions on coast of British Columbia

FROM THE JOURNAL OF C. F. NEWCOMBE.

In: REPORT OF THE COMMISSIONER OF FISHERIES. R127-139.

[These are notes produced by Charles Newcombe in preparing for his two publications: (1) Newcombe, C. F., and W. A. Newcombe. 1914. Sea-lions on the coast of British Columbia, Report of the Commission of Fisheries for 1913. 131-139 pp. (2) Newcombe, C. F., W. H. Greenwood, and C. McLean. 1918. Preliminary report of the Commission on the sea-lion question, 1915. B.C. sea lion investigation, special commissioner’s preliminary and main reports. Contributions to Canadian Biology (Studies from the Biological Stations of Canada 1917-1918), Supplement to the 7th Annual Report of the Dept. of the Naval Service, Fisheries Branch (8 George V, Sessional Paper No. 38a). 5-52 pp.]

“Quatsino V.I. – 1913. Chief Pasen, of Kwatsenoq (Charlie), working at the Wallace cannery stated: –

Food.-All kinds of fish; halibut, salmon, black cod, herring, etc.

Breeding-time.-Salmon-berry month, i.e., early June.

Chief Charlie has now no particular use for the sea-lions, and has no objection, therefore, to their being killed. Would gladly help if he could be sure of a bounty. When out of oolachan-grease he sometimes uses sea-lion blubber, but would not go out of his way to get one.

Killing – The easiest way to get them is on the islands where they breed. Could kill any number of young when the mothers are in the water after food. He thinks that some of the young males do not go every year to the islands.

Hair-seals. These breed on low rocks, sometimes on those generally awash, but not in the open sea.

Chief Phillip, of Koskimo, confirms all the above. When seen on the small island in front of the Quatsino Cannery, he and his wife were engaged in trying out the fat of a young sea-lion on the beach. This they had just killed when in search of sea-eggs. The blubber from under the skin had been cut up into chunks and was being boiled down, with a very little water to start the melting, in an iron pot.

Chief Sakius, of Koskimo, says that in former days his people used often to go to Solander island after sea-lions. Their name for the island is Tleixdema, which means the “Place of Sea-lions.” They consider that the island is a whale, which was turned into stone at the time a great flood. The highest point is the back fin of the whale, and there is a small spring of water here. Near this fin is a hole through the rock, and when there is a heavy sea on, spray dashes through it and looks like the stream from a whale blowing. The whale’s head points towards the north-west; near the tail (i.e., to the south-east) is a small canoe harbour. In old days this island was the property of the Nootkan Tribe, called Tseketlisatuq, who are called Checkleset by the whites, but the Kwakiutl Tribe, called Tlaskino, who used to live in Klaskino Inlet, took it away from them after a fight. Sea-lions eat too many salmon, halibut, and black cod, so Sakius would be glad to see their numbers reduced. No Indians are now hunting them or using them, and there is no market for their skins. The best place to kill them is on their breeding islands. In former days, sea-lion bladders, inflated, were sometimes used for floats when hunting for whales, and common seal-bladders for halibut.

Hair-seals. These are bad for fish also. They bear their young, mostly in this locality, on all rocky islands inside Quatsino Sound.

Triangle Island is one of the great breeding-places for sea-lions. It is called Heitlas, and is owned by the Nahwitti. The Haycocks are called Nagoiawitli, or middle islands, and the Lanz Islands, Numasdema, or Old Man’s Island. The last has a fine harbour, and on it in old days the Indians used to drive the sea-lions towards their houses and kill them with clubs. The nearest island of all is called Yutli. There used to be a permanent village here called Yutlinu. The last of this tribe (Yutlinu) still live at Humtaspi. They used to have small totem-poles at their village.

Sakius added that if a bounty were put on sea-lions the young men would go after them with clubs, as in the old days. They could do better this way than with guns, as they would scare them all away.

In the old method the young men ranged themselves along the lanes which the sea-lions followed when hauling out of the water, and were placed in two ranks, one on each side of the lane, but not standing opposite one another. So if a man on one side failed to kill a sea-lion, the next man, who would be on the opposite side, would have a good chance to strike. big sea-lions were seldom killed. They were always at the highest points and it was too hard to kill them with clubs.

When hunting the sea-lion in the water they used harpoons with bladders attached to the lines as floats. These harpoons were thrown clear of the hunter and were not used as lances.

They were two-pronged, with finger notches just like the present fur-seal spear: the only difference being the addition of the seal-bladder float. Mussel-shells were formerly used for the points.

Solander Island.-No one ever stays overnight on this island on account of a huge devil-fish which reaches out of the water with its arms to find if any human being is on the island. 1f it finds any one, it quickly kills and eats him. It has no special name, though the common name for devil-fish is Tekwa. Such man-eating by devil-fish has not been observed anywhere else.

The following is the story about Solander Island: Two Klaskino Indians went halibut-fishing near Cape Cook (Ewala). They went ashore on Solander for devil-fish bait, landing where there was a horizontal fissure in the rock. Then the sea began to boil, and they knew that a sea-monster must be near (iakim). Floating past came a number of Indian boxes, other house- hold property, and a number of kelp-stems. Then they saw something red, which turned out to be the arm of an enormous devil-fish. They hastily hid themselves in a vertical crack in the rock, but the arm kept feeling about, and at last a head came up from the sea and then slowly drew back, followed after a time by the arms. These were long enough to have reached from the sea to the top of Solander Island.

Sagius himself would on no account sleep on the island, on account of this beast. He claims that he once saw six deer on it, and old people say that at one time there was always a small band there.

Rivers Inlet.-Chief Hitlamas, of the Wikeno band, says that there is a very old rookery in the Sea Otter Group of Islands. Some of the oldest traditions of the tribe relate to it. In early times the people used to go to the west side of Calvert Island in the sockeye season to kill sea-lions. In those days clubs were used, and double lines of armed men used to be formed on the rocks, just as reported at Quatsino. The bodies were used both to provide meat and grease for food. Informant and one other man are all that are now left of the old band of hunters. In early days two old sea-lions used to guard the only approach to the summit of the principal rookery, and these used to bite at any hunter getting too close. A man was once picked up by one of these watchmen and thrown into the sea. In a group of islands there are three on which sea-lions breed. On one of these is a small harbour fit for canoes in calm weather. On one of them is also a small lake of salt water, called Ohsta, in which sea-lions hide when chased. In sockeye season these rookeries are covered with red-coloured excrement. A long time ago the Indians used to take sea-lions in pond just mentioned by strong nets made of nettle-fibre string.

Alert Bay-April 26th, 1913. A sea-lion was shot by Ned Harris, an Alert Bay Indian, off Pearce Island, about two miles away. To prevent it from sinking he at once made a slit through the skin of its head, passed a line, and towed it to the nearest beach. Being alone in a small fishing-canoe, he then made for Alert Bay for a gasolene-launch to bring it in. They arrived about 6 p.m., where I saw the carcass being hauled out by about twenty men to the tune of an old song used on such occasions. The measurements were as follows:

From tip of snout to end of flippers – 12 feet.

Round the neck, just back of the skull – 4 feet 6 inches.

From the resting-place of one shoulder to same place on the other side – 5 feet.

Averages along the ground, from side to side – 5 feet 4 1/2 inches

Weight measured by courtesy of M. H. Chambers, of Alert

Bay Cannery, with scales-

Meat – 1690 lb.

Blood – 100 lb.

Skin and some of the bones – 450 lb.

Total – 2,240 lb.

The following notes were furnished by Captain C. Spring:

– Nawhitte.-May 1st, 1913. King Tom’s information. King Tom’s information. The Pearl Rocks are the only group in Queen Charlotte Sound on which sea-lions have their young. This is in June, on the islands called Wawis. Some time ago Tom and three other men left Nawhitte at 5 a.m. and returned he same day with fourteen young sea-lions about two weeks old. Most were clubbed, some shot with an old H.B. trade gun, ball being used. On one island is a small basin, with many sea lion whiskers. At high water this basin is connected with the sea. It is a good place to land on south side of largest rock, but only in fine smooth weather.

The Scott Islands.-The East Haycock, or Numasta of the Indians, contains a small boat on the west side. The sea-lions have their young on an outer rock to the north-west side of Haycock. There is an anchorage called Tekal on the south-east side.

Triangle Island contains two breeding-places on detached rocks, one to the east of island, called Khera-mola. On the south side of it is a good gravel beach to land on. On the north-west side is the other rookery, Cla-wis. This is reported to have both sea-lions and wig-seals. Another are said to be white on the forehead, and is called Tsi-kin by the Indians.

From Albert Thompson, of Wikano, re Queen Charlotte Sound rookeries. There is good anchorage at south of Cape Calvert, opposite Sorrow Island, sea-lions have their young any time after June 15th. The mothers stay on the rocks for about three weeks, and then they take to the water, but always return to the rocks. Indians used to club old as well as young sea-lions. Parents are very affectionate and will take the young in mouth when they go into water.

From Johnny Davis, a Skidegate Haida living at China Hat (Indian name Git-cum). On Green Charlotte Islands the only rookery that J. D. knows of is that at Cape St. James. Other places used by them on the mainland side are merely stopping-places.

At Metlakatla, Indians said that there is a rookery outside of Stephens Island where young are brought forth about the middle of June.

From Timothy Tait, of Ninstints Village, Q.C.I. To land on the rookery at Cape St. James the tide should be from west or north-west, and the landing should be made during ebb tide. When a west wind has been blowing for two days, then make a try on the east side of the island. Sea-lions are always afraid of a man and have never been known to attack one. Young are brought forth in July. “

References

Barnett, Homer G. 1955. The Coast Salish of British Columbia. University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon. The University Press.

Boas, Franz.1921 a. Ethnology of the Kwakiutl. Bag of Sea Lion Hide. Twenty-Fifth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology. Part 1. Washington, Government Printing.

Boas, Franz.1921 b. Ethnology of the Kwakiutl. Paintings and House Dishes of the Social Divisions of the KwÃGU£. Twenty-Fifth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology. Part 2. Washington, Government Printing.

Cox, Ross 2004. Adventures on the Columbia River. Six Years ln the Western Side of the Rocky Mountains. The Narrative Press. Number 87. In the Historical Adventure and Exploration Series.

Colten, Roger, Jeanne E. Arnold. 1998. Prehistoric Marine Mammal Hunting on California’s Norther Channel Islands. American Antiquity, 63(4):679-701.

Elliott, Henry W. 1886. An Arctic Province. Alaska and the Seal Islands. Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, London.

Elmendorf, W.W. 1960. The Structure of the Twana Culture. Research Studies. Washington State University. Monographic Supplement No. 2. Pullman Washington.

Egeland, Charles P., Briana L. Pobiner, Stephen Merritt and Suzanne Kunitz. 2024. Actualistic butchery studies in zooarchaeology: Where we’ve been, where we are now, and where we want to go. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. Vol. 73:1-14. 101565.

Flenniken, J. Jefferey. 1980. Systems Analysis of the Lithic Artifacts. In: Hoko River: A 2500 Year Old Fishing Camp on the Northwest Coast of North America. Edited by Dale R. Croes and Eric Blinman. Washington State University Laboratory of Anthropology Reports of Investigations No. 58:290-307.

Guiguet, Charles J. 1971. An apparent increase in California sea lion, Zalophus californianus (Lessen), and elephant seal, Mirounga angustirostris (Gill), on the coast of British Columbia. Syesis Vol. 4:263-264.

Hall, Roberta I. 2001. Nah-so-mah Village Viewed Through Its Fauna. Department of Anthropology, Oregon State University, Cornvallis, Oregon.

Huelsbeck, David R. 1984. Mammals and Fish in the Subsistence Economy of Ozette. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, Washington State University, Pullman, Washington. University Microfilms, Ann Arbor.

Huelsbeck, David R. 1988. The Surplus Economy of the Central Northwest Coast. In: Prehistoric Economies of the Pacific Northwest Coast, edited by Barry Isaac, Supplement 3 of Research in Economic Anthropology pp. 149‑177. JAI Press, Greenwich, Connecticut.

Keddie, Grant. 2023. The Human and Natural Modification of Bone Assemblages From Mountain Caves And Rock Shelters On Vancouver Island. Grantkeddie.com

Keddie, Grant. 2006. The Early Introduction of Iron Among First Nations in British Columbia. Living Landscapes Project. Upper Fraser River Basin. Royal B.C. Museum Web Site Publication.

Kennett, Douglas J. and James P. Kennett. 2000. Competitive and Cooperative Responses to Climate Instibility in Coastal Southern California. American Antiquity. 65(2):379-395.

Krober, A.L.1960. Comparative Notes on the Structure of Yurok Culture. Research Studies. Washington State University. Monographic Suppliment No. 2. Pullman Washington.

Lyman, R. L. 1995. On the Evolution of Marine Mammal Hunting on the Northwest Coast of North America. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 14:45-77,

Lyman, R. L. 1989. Seal and Sea Lion Hunting: A Zooarchaeological Study from the Southern Northwest Coast of North America. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 8:68-99.

McKechnie, Iain and Rebecca Wigen 1911. Toward a Historical Ecology of Pinniped and Sea Otter Hunting Traditions on the Coast of Southern British Columbia. In: Todd Braje and Torben C. Rick (eds) Human Impacts on Seals, Sea Lions, and sea Otters. University of California Press, Berkeley. Pp. 129-166.

Nagorsen, David W., Grant Keddie and Tanya Luszcz. 1996. Vancouver Island Marmot Bones from Subalpine Caves: Archaeological and Biological Significance. Occasional Paper No. 4. Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks.

Newcombe, C.F., W.H. Greenwood, and C.M. Fraser. 1918. Part 1. Preliminary report of the Commission on the sea lion question, 1915. Part 2. Report and conclusion of the sea lion investigation, 1916. Contributions to Canadian Biology p. 1-19.

Newcombe, C.F. and W.A. Newcombe. 1914. Sea lions on the coast of British Columbia. Annual Report of the British Columbia Commission for Fisheries for 1913 p. 131-145.

Olesiuk, P.F. 2008. Abundance of Steller sea lions (Eumetopias jubatus) in British Columbia. DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Res. Doc. 2008/63. iv + 29 p.

Olesiuk, Peter F. 2018. Recent Trends in Abundance of Steller Sea Lions (Eumetopias jubatus) in British Columbia. DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Res. Doc. 2018/006. v + 67

Porcasi, Judith F., Tery L. Jones and I. Mark Raab. 2000. Journal of Anthropological Anthropology 19, 200-220.

Pope, Saxton T. 1923. The Study of Bows and Arrows. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology. Vol. 13. No. 9. Pp. 329-414. Plates 45-64. University of California Press, Berkeley, California.

Rozen, David L. 1978. The Ethnozoology of the Cowichan Indian People of British Columbia. Volume I. Fish, Beach Foods, and Marine Mammals.

Scheffer, Victor B. 1958. Seals Sea Lions and Walruses. A View of the Pinnipedian. Standford University Press. Standford California.

Scheffer, Victor B. 1948. Use of fur seal carcasses by Natives of the Pribilov Islands, Alaska. Pacific Northwest Quarterly. 39:131-133.

Suttles, Wayne. 1987. Notes on Coast Salish Sea Mammal Hunting. In: Coast Salish Essays. University of Washington, Talon Books. Pp.233-247. (From Anthropology in British Columbia. 3:10. 1952).

Swan, James G. 1992. The Northwest Coast. Or, Three Years’ Residence in Washington Territory.