Introduction

A period of Destruction and Realignment

The W̱SÁNEĆ, Tommy Paul, referred to an epidemic that devastated his people six generation before him: “That terrible sickness. It is true. It belongs to the story of my Chilangwin” (Lugrin 1931). Elders told the story of “Kwalarhunzit” who began his training as a warrior at 13 years of age after “a terrible epidemic of smallpox had just decimated the Saanich Indians and crippled their resistance to the raids of their enemies. …His first fight was against some southern natives who were visiting relatives at the big settlement near Sidney”. At this time there was a village of people on Mayne Island who invited Kwalarhunzit to a deer hunt but ended up fighting with him (Jenness 1934-36).

This story refers to the Smallpox of 1780, that spread from the eastern United States before Europeans visited the Salish Sea. When the first European came into the area they observed old smallpox scares on people of the age that fit the 1780 epidemic. Kwalarhunzit would be at least 20 years old when involved in his warrior activities. This would suggest that the old village of “Sai’klam” in Tsehum harbour (What I interpret as the “big settlement near Sidney “) was still occupied around 1790, before it moved to Pat Bay.

As the W̱SÁNEĆ would have been realigning themselves from a large population reduction, another major disruption occurred in the early to mid-1800. They were attacked by the Lekwiltok and their alias from the north, and after 1853 from the Haida, when the latter started visiting the Victoria region (see Appendix 2. Late Aggressions). For a review of the Census of Saanich people 1826-1856, see See Appendix 1.

Many W̱SÁNEĆ residents of the Gulf Islands moved to join others on the East side of the Saanich Peninsula, and then some to the west side, to escape the violence. All the speakers of the Coast Salish language family, including those as far south as Seattle, were the target of raids for slaves and plunder (Kennedy and Bouchard 1991; Curtis 1913; Suttles 1954; Boas 1890; Hill-tout 1907).

Saanich oral tradition records that the village of “Sai’klam” in Tsehum Harbour, just north of Sidney, was abandoned and the people established a settlement in Patricia Bay in Saanich Inlet. The previous occupants of Patricia Bay had abandoned it and fled to Marietta, Washington, after a fight with the Mill Bay people (Jenness 1934 1936; Turner and Hebda 1989).

Stories were told that kwe16xwenthet was the “forefather” of all the Tsartlip people. He was said to have moved to Tsartlip from a creek at East Saanich to escape the war attacks. Tommy Paul told Barnett that “the former inhabitants there [at Tsartlip] were all dead” by the time kwe16xwenthet arrived, but he did not identify who these former residents were” (Barnett 1938; 1955).

We know the Tsartlip were on the east side of the Saanich peninsula in 1854 (Pearse 1900) and the next year their village appears spelled as “Chawilp” at the Tsartlip reserve location on Pemberton’s 1855 map.

Jenness was told: “the West Saanich natives attribute the destruction of their old village in Brentwood Bay, about 1850, to either Comox or Kwakiutl Indians (they are uncertain which), who attacked the settlement at a time when nearly all its inhabitants were fishing on the opposite shore of Saanich Inlet near Malahat and burned its three long, shed-roofed houses, as well as several smaller ones.”

The Pauquachin village was said to have been founded by people from the Malahat village. It does not appear on Pemberton’s 1855 map. A possible clue to the identification of some of these earlier residents of Saanich Arm was provided by W̱SÁNEĆ, Chistopher Paul, who noted that several Saanich Arm place names are in the Halkomelem language, rather than in the Northern Straits language.

All of these extended families have now intermarried with each other and outsiders to became the four bands of W̱SÁNEĆ and the Malahat, as we know them today.

The Goldstream River Delta

The Goldstream River has long been an important fishing resource area for the Malahat people who once spoke a Halkomelem language and the W̱SÁNEĆ communities speaking the SENĆOŦEN language.

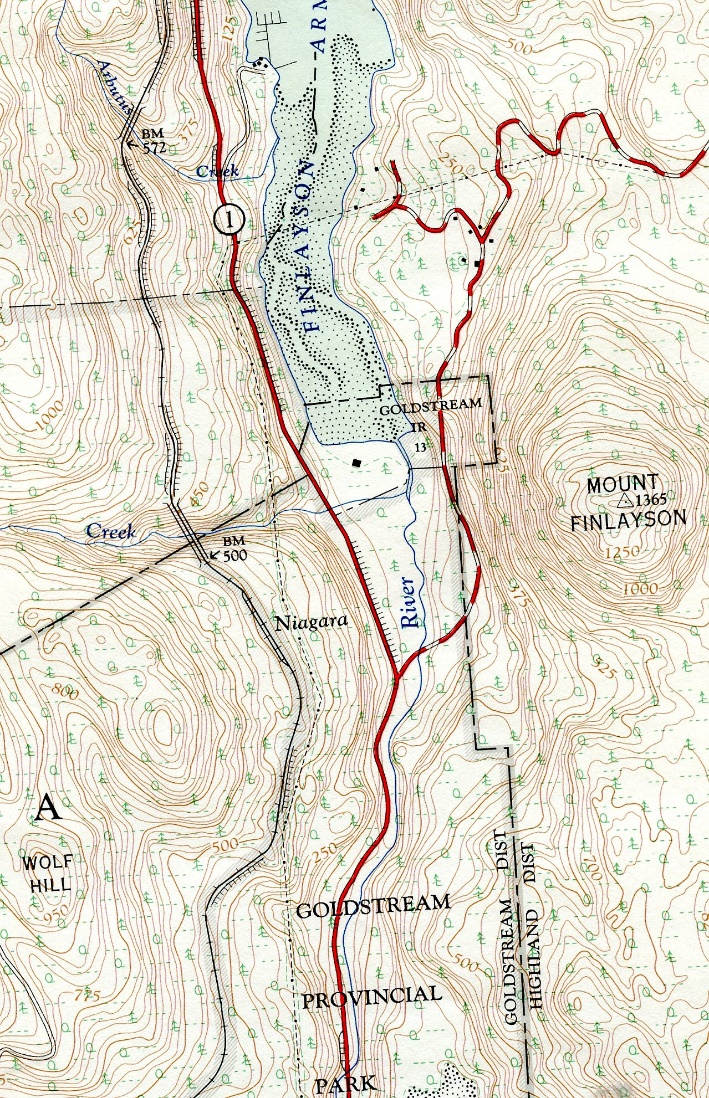

In the fall, Indigenous people fished for chum, coho and pink salmon and steelhead. Spring salmon and trout could be fished there in the spring. In 1877, the Indian Reserve Commission recognised the historic importance of the Goldstream River and allotted a fishing reserve along the east side of the rivers entrance at the south end of Finlayson Arm. This was called Goldstream Reserve no. 13 (Figure 3), and is today, under the jurisdiction of five Indigenous bands, the Malahat, Pauquachin (BOḰEĆEN), Tsartlip (W̱JOȽEȽP), Tsawout (SȾÁUTW̱) and Tseycum (WSÍKEM). (Commission 1877).

19th century images of the activities at the Goldstream River mouth are either rare or almost non-existent. However, a unique oil painting of the Indigenous use of this location was produced by the English painter John Paramor (1858-1920), entitled “Saanich Arm Indian encampment”. He painted it during a visit to Canada in 1885. I was able to acquire a copy when it was in a private collection (Figure 4).

This wonderful painting of people at the fishing site, shows in the left background, a village of several houses. There appears to be two small tradition style cedar plank houses, one European style house and several smaller temporary structures. This location was not recorded as an archaeological site.

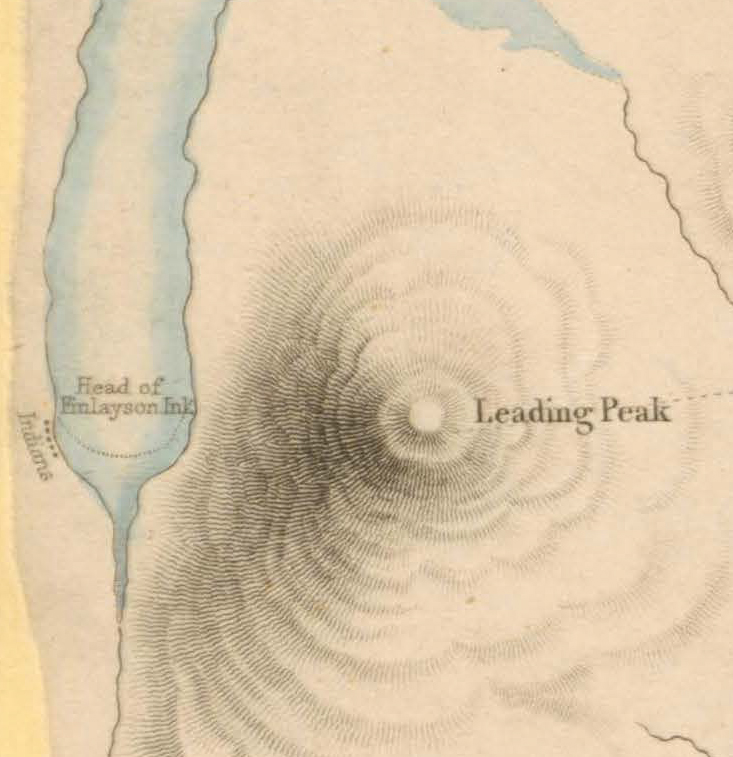

Houses at the same location as seen in figure 4, are marked on the Arrowsmith map of 1854 (Figure 5). Other locations on the Arrowsmith map show small squares representing houses. There are five houses on the west side of the mouth of Goldstream River. Above the houses is the word “Indians”. Words printed across near by say “Head of Finlayson Inlet”. The script in the middle of the Inlet is: “Finlayson or Saanich Inlet. The Entrance to this Inlet is 17 Miles N.N.E. from the Head”.

Figure 5. Small portion of Map of the Districts of Victoria and Esquimalt in Vancouver Island by J. Arrowsmith, 1854. Hudsons’s Bay Company Archives map collection, G.3/96.

The closest recorded archaeological site to this location, is a shellmidden site of unknown age, further up the inlet on the west side near Arbutus Creek. The site DcRv-44, is 20-30 meters north of the mouth of Arbutus Creek, 2 to 3 meters above the highwater mark. It is 6 by 8 meters in dimension and about one meter deep.

There are a few recorded SENĆOŦEN language place names in this area, but it is difficult to pin down to specific locations. One name SELECTEL is interpreted as “The People downstream” and at the “Goldstream end of Finlayson arm, southwest side”. Another name is TQELNEL, interpreted as “to expire” and referring to the: “Area at mouth of Goldstream, including Island”. Another word, MI,YO,EN “becoming less”, is at the same location as the last name ” (Montler 2018; 1981; Elliott and Poth 1984; Paul 1995; Hudson 1970).

Appendix 1. Census of Saanich people 1826-1856

1826-27. The Archibald McDonald “Report on Fort Langley” 1830 with data collected about 1826-27 lists “Sanutch” with 60 “men” and “Chief” named “Tcheenuk”.

1829. The Fort Langley Hudson’s Bay Journal reports on July 11, 1829: “Cheenuck – one of our best traders from the South end of the island is in with only 5 skins”. Earlier on January 17, his name is spelled as “Chinuck”, who “came in today with 18 Land otters & 2 beaver skins”. But he is miss-identified as “One of the Sandish Indians”. Sandish was a head man of one of the Kwantlen peoples. Sandish’s followers were sometimes referred to as “the Sandish Tribe”. The name Sandish, should not be confused as referring to the name Saanich.

1839. In 1839 a “Population of Indians at Fraser’s river” (Hudson’s Bay Company Archives B.223/2/1) lists the “Eusanich” – “East side Vancouver Island in Canal de Arro” with 12 heads of Families, 50 canoes, 15 guns, 30 women, 21 Sons, 13 Daughters, 107 Male and Female Followers. Total 183.

1841. An 1841 list in the possession of William Tolmie lists “Sanetch” – “500 souls, inhabiting N. E. [of Island] 10 miles N.W. of Mt. D’g’s [Douglas].”

1848. A census know to be in the possession of Roderick Finlayson of the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1848 lists 4 groups under “Sanetch”. This part of the census was probably taken in 1845 because the total of 445 people is also given in the Warre and Vavasour census shown in a report of October 26, 1845. It is known that Finlayson undertook a count of the Clallam in 1845 who are also on the 1848 list and show the same total on the 1845 Warre and Vavasour list.

The Finlayson 1845 “Census of the following tribes of Indians inhabiting the Straits of Juan De. Fuca” is found with other census in the “James Douglas Private Papers”. “Census of Indian Population in Vancouver Island and B.C.” Provincial Archives and Government Records Branch B 20/1853.

The Finlayson list is as follows (not including individual numbers of men, women and children):

Names of Tribes. Names of Chief’s. Total: (All 445).

Sei Chum Squoil-tun 154

Mala-chult Selp-queinum 151

Tsolulp Muk-muka-tun 111

Semi-ama Squsa-letse 29

The “Tsolulp”, or as called later “Tsartlip”, lived on the East side of the Saanich peninsula in 1853 when the land surveyor Benjamin W. Pearse visited, but had moved to the west side where they are shown at their village, spelt as “Chawilp”, at the Tsartlip reserve on Pemberton’s 1855 map. “Muk-muka-tun” of the 1845 census is the same person as “Mook mook-tan” mentioned below by Pearce. He was chief of the Tsartlip.

Benjamin Pearse wrote: “In 1853 we went to examine the coals reported to exist at Saanich , travelling thither in a canoe with five French-Canadian voyageurs as crew . On arrival at the Saikum village , we obtained the assistance of the chief , who showed us the black stone , but it proved to be only lignite. Whilst we were having lunch the [written in by someone else? – ‘Pen-al-ahut Indians’], under their old chief, Mook-mook – tan , having sighted us, and being always in those days on the lookout for enemies , began to get excited and to yell and fire guns , whereupon our men, more experienced than we were with Indians, advised us to get away quietly , fearing mischief . This we endeavored to do, but the Indians mustered in force and gave chase, firing and shouting at us for miles. We had, however, seven paddlers, five of whom were very perfect, and we gave them “leg-bail” arriving in safety at Cordova Bay, where we encamped for the night. This old Saanich Chief was for years afterwards one of our most faithful friends and servants”. (Pearce 1893).

In 1931, Nancy deBertrand Lugrin interviewed Mary Seaultanat, the 85-year-old daughter of “Mook mooktin”, on the Tsartlip Reserve:

“Her father was Mook Mooktin and her grandfather was Quilawshokitwa. The grandfather and father were, in succession, chiefs of the Tsaultups, the tribe living on the West Road”.

One of the Saanich “Tribes” of 29 people is listed by Tolmie in 1845, is “Semi-ana” with the chief known as Squsa-letse. Where they were located is not known. Although the name may be related to an individual rather than what one might assume being linked to the Semi-amoo of the Campbell Creek area on the mainland.

Mary Seaultanat, of the Tsartlip Reserve, was married at age 14 “to Chislut, who was a Tsout Indian. Tsout is the Indian name for the East Saanich Reserve. His mother was a Simiana Indian from Port Angeles and white people used to call Chislut Simiana Jam” (Lugrin 1931). This would suggest that the Semi-ama” tribe listed by Finlayson in 1845, is the Tsawout First Nation of today.

1852. Douglas Treaties of 1852 lists “South Saanich” “between Mount Douglas and Cowitchen Head” and “North Saanich” – 117 men of 3 villages.

1855. Pemberton map of 1855 shows three Saanich villages and one Malahat village:

“Tetaihit” at the present Tsawout Reserve; Siakum at the present Pat Bay reserve; Chawilp” at the Tsartlip reserve and “Malahalh” at the present Malahat reserve.

1856. In the Douglas Papers is an 1856, list on the Saanich. The “Original Indian Population” lists “Sanitch” – “Mount Douglas” as having 10 men with beards, 12 women, 16 boys, and 18 girls for a total of 56. And “Sanitch” – “Sanitch Arm” as having 118 men with beards, 130 women, 210 boys and 225 girls for a total of 683.

Appendix 2. Late Aggressions

Walter B. Anderson told a story that relates to the experience of his father, Alexander Caulfield Anerson, who was assigned local judicial powers in Saanich in the early 1860s. Alexander C. Anderson and family moved to Saanich on Rosebank farm, next to the Tseycum (WSÍKEM) Reserve. In the Fall of 1861. Walter Anderson noted: “The Say-ah-Coom tribe (Sayak meaning clay, in allusion to the clayey nature of the soil there, hence Say-ah-Coom, the place of clay). These Indians soon became good neighbours, as finding my father sympathetic and kindly disposed toward them, they in time came to look upon him as a sort of guardian”.

Walter Anderson indicates that the Haida: “were at this time the terror of all the southern coast tribes”. He tells: “a story of a massacre which took place a few years after our homesteading at Saanich”. It is titled “Indian Family Slain”:

“The then chief of the Say-ak-Coon tribe was a man named Kalalukhwa, a tall, immensely powerful Indian. If I remember aright, he was close to seven feet tall, with immense limbs well clothed with great masses of thews and sinews. In passing through an ordinary doorway he had to stoop to ensure head clearance.

One fine Spring day the chief, his wife, with several young girl relatives took canoe to the island “Thlalatchin” (Moresby) in order to fish and to gather certain roots for food. They were to be gone several days, but when the time had elapsed and they did not appear, some men relatives of the tribe went in search and found the beheaded corpses of six of the party in their camp on the island, where they had apparently been stolen upon in the night by a band of Hydahs. One girl, the eldest of the younger people, was missing and could not be found. The bodies were brought back to the village and word was sent to my father of the crime. He, as Justice of the Peace, went down and viewed the six headless corpses as they had been laid in a row on the beach, a truly gruesome sight.

Though signs pointed to Hydah work, it was found impossible to take any steps toward apprehending the murderers. In those days water travel was slow. The coast north of Comox was entirely unpopulated by whites and doubtless by the time any force could have been sent in pursuit the perpetrators would have been beyond overtaking.

References:

Anderson, Walter B. 1937. Chronicles of Old North Saanich. The Daily Colonist, Victoria, B.C. June 6, Page 3.

Barnett, Homer G. The Coast Salish of Canada. American Anthropologist, Vol. 40, pp. 118-141, 1938.

Barnett, Homer G. 1955. The Coast Salish of British Columbia. University of Oregon.

Barnett, Homer G. 1935-1936. Coast Salish Field Notes. University of British Columbia Library, Special Collections Division, Vancouver. Homer Barnett Papers, Box 1.

Boas, Franz. 1890. Second General Report on the Indians of British Columbia. Report of the Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, 1886-1889, 1890, pp.562-583. Reprinted in Northwest Anthropological Research Notes, Fall\Spring 1974, Vol. 8, No. 1\2.

Curtis, Edward S. 1913. Salish Tribes of the Coast. The North American Indian. Vol. 9, pp.175, Norwood, Mass.

Duff, Wilson. 1969. The Fort Victoria Treaties. B.C. Studies, no.3, Fall, pp. 3-57.

Elliott, Dave Sr. and Janet Poth (Editor) 1984. Salt Water People. A Resource Book for the Saanich Native Studies Program. Native Education, School District 63. Saanich.

Hill-Tout, Charles. 1907. Report on the ethnology of the southeastern tribes of Vancouver Island, British Columbia. Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. vol. 37, pp. 306-374.

Hudson, Douglas. 1970. Some Geographical Terms of the Saanich Indians of British Columbia. With information from: Mr. Richard Harry, East Saanich; Mr. Ernie Olsen, Brentwood Bay; Mr. Christopher Paul, Brentwood Bay; Mr. Louis Pelke, East Saanich. Compiled by Douglas Hudson, Department of Anthropology, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario.

Kennedy, Dorothy and Randy Bouchard. 1991. Traditional Territories of the Saanich Indians. Prepared for: Treaties and Historical Research Centre. Comprehensive Claims Branch. Indian and Northern Affairs. Ottawa.

Jenness, Diamond. C.1934-36. Coast Salish Field Notes. Ethnology Archives,Canadian Museum of Civilization, Hull, Quebec. Ms #1103.6. (pp.146).

Jenness, Diamond. C. 1938. The Saanitch Indians of Vancouver Island. Unpublished manuscript. Ethnology Archives, Canadian Museum of Civilization, Hull, Quebec. Ms #1103.6 (pp.111, plus Appendices).

Lugrin, Nancy de Bertrand. 1931a. Soliloquies in Victoria’s Suburbia. No. XI. Victoria Daily Colonist May 5, 1931.

Lugrin, Nancy de Bertrand. 1931b. Soliloquies in Victoria’s Suburbia. The Victoria Daily Colonist. September 20, 1931.

Montler, Timothy. 2018. SENĆOŦEN A Dictionary of the Saanich Language. University of Washington Press.

Montler, Timothy. 1981. Saanich, North Straits Salish. Classified Word List. Canadian Ethnology Service. Paper No. 119 Mercury Series. Canadian Museum of Civilization. Hull, Quebec.

Paul, Philip Christopher. With Philip Christopher Paul, Eddy Carmack and Robie MacDonald. 1995. The Care Takers. The Re-Emergence pf the Saanich Map.

Paramor, John. 1885. “Saanich Arm Indian encampment”. Oil on Canvas 24” by 36” by John Paramor (1858-1920). Born in England. Travelled to Canada as a young man. Studied in London in 1878. returned to Canada in the h1880s. The painting was once sold by Gary Spratt Fine Art. Later owned by Uno Langmann Limited fine art.

Pearse, Benjamin W., Early Settlement on Vancouver Island, manuscript dated 1900 (BCARS – E/B/P31), p. 11.

Pearse, Benjamin W. 1893. IN MEMORIAM. British Colonist 1893, Nov 14, p. 6.

Commission 1877. Report of the Proceedings of the Joint Commission for the Settlement of the Indian Reserves in the Province of British Columbia, 21st March 1877. National Archives of Canada, RG 10. Vol. 3,645, File 7,936.

Suttles, Wayne P. 1974. Coast Salish and Western Washington Indians I. The Economic Life of the Coast Salish of Haro and Rosario Straits, Garland Pub., New York, 1974.

Suttles, Wayne P. 1954. Post-Contact Culture Changes among the Lummi Indians. The British Columbia Historical Quarterly, Vol. XVIII, Nos. 1 and 2, pp. 29-102.

Turner, Nancy J. and Richard J. Hebda. 2012 Saanich Ethnobotany. Culturally Important Plants of the W̱SÁNEĆ People. Royal B.C. Museum Publications.