Part 1. The changing Landscape and Victoria Harbour to Selkirk Waters.

The Changing Landscape

Twenty-one thousand years ago the Gorge Waterway, Victoria Harbour and all the beaches around Victoria were all deep underwater. This was caused by the glaciers pushing the land down as they approached the Victoria Region (Miskelly 2012; Clague 1983). The land rebounded to 14 meters above the present sea level by Thirteen thousand years ago (Keddie 2019).

By 11.200 years ago the land continued to rebounded and the Gorge appeared for a short period of around 1,000 to 2000 years as an ocean inlet. As the land continued to rebound, the upper Gorge became dry land by 9200 years ago. The Gorge and Victoria Harbour became merely a creek as the rising land expanded to include shorelands beyond present day Victoria that are now underwater up to 45 meters.

The rebounding of the land stopped and the land began to sink in relation to the Ocean. Any Indigenous villages that may have been along the expanded shoreline would be washed away between about 8000 and 4500 years ago as the land sank, allowing the ocean to move back in to near where it is today.

Radio carbon dates show that the ocean had come back into James Bay in the Inner Harbour and to the Gorge Falls under the Tillicum Road bridge by 4200 years ago (Keddie 1991).

Defining the Boundaries

The start of the Gorge Waterway is defined here as starting at Victoria’s inner Harbour. There is the “Outer Harbour” which includes a more exposed area at its south end – that is from Ogden Point to Shoal Point on the east side and on the west side from McLoughlan Point to Work Point. The northern part of the “Outer Harbour” is more protected – that is the area extending into West Bay and along the north shore to Colville Island.

The Inner Harbour is composed of a western section between Lime Point on the north shore and Shoal Point on the south shore, and an eastern section located beyond the narrowing of the Harbour at Laurel and Songhees Points. This area includes what is left of the old James Bay – now much filled in. There is also the “Upper Harbour” which extends from the narrowing of the harbour between Limit Point and Halkett Head, at the Johnston Street Bridge, north to the narrowing at the site of the Point Ellis (Bay Street) Bridge.

The Archaeology of Victoria Harbour

The Lekwungen had large winter village sites around the greater Victoria Region, but not in Victoria harbour itself. Victoria harbour was not a suitable place for large winter village sites. The harbour was rocky and the winds and currents made it a difficult place to get in and out of during bad weather. Victoria Harbour and its extension up the Gorge waterway was primarily a place for important seasonal resources. Winter villages were more likely further up the Gorge Waterway.

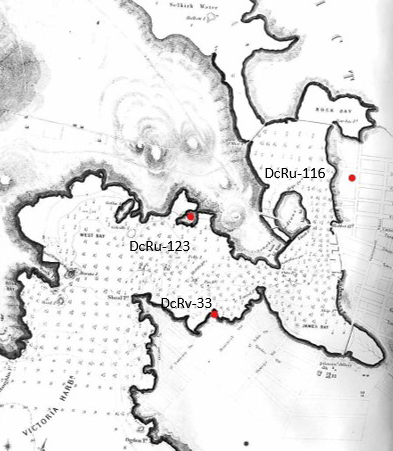

There is evidence of three ancient shellmidden sites in Victoria’s Inner Harbour. The Capital Iron site, DcRu116, was located above a high rocky shore on the east side of the Upper Harbour along Wharf Street between Chatham and Discovery Avenues, just south of Rock Bay. The charcoal sample I extracted from the lower intact deposits of this site was radio-carbon dated to around 1600 years ago. This location was occupied for a few hundred years, starting around 260 to 424 A.D. It was likely occupied on a seasonal basis. Disturbed upper deposits, prevented the ability to determine if the site was occupied in late pre-contact times. For more detail see (Keddie 2018). Figure 2, shows buried shellmidden.

Two seasonal camps were located in the inner harbour outside of the narrow constriction at Laurel and Songhees Points.

The Raymur Point shellmidden site, DcRu-33, is located on a raised bedrock peninsula on the south side of the harbour. The mostly flaked stone artifactual material found at DcRu-33, and the few diagnostic styles indicate that the site is an old one – likely pre-dating 1000 years ago. One human burial was recovered from the site (later reburied). The limited number of artifact types and the lack of faunal remains do not allow us to say anything about seasonality at this site. For more detail see (Keddie 2017).

Another shellmidden is found on the Lime Bay Peninsula at the north entrance to the inner harbour just East of Catherine Street. The latter is a defensive site – defined by the presence of a deep trench around the back of the peninsula. I radio-carbon dated this shellmidden site to the period between at least 1200 to 600 years ago. It was occupied, at least intermittently, during this time period. The limited number of artifact types and the preponderance of anchovy and native oyster shells in the faunal assemblage, suggests that this site is more likely a seasonal site and not a winter village site. Anchovies once came into this area in greatest numbers during the month of July. For more detail see (Keddie 2023a & 2023b). Figure 4, shows the Lime Bay Site, DcRu-123, once extending along the waterfront at the mid-centre of the photo and underneath the large condominium at centre. The building on the right is located in what was once part of mud Bay.

There are no pre-contact shellmiddens in the Inner Harbour East of Laurel Point. One site, DcRu154, was earlier recorded, but now rejected as a site. It was located up a creek that once drained into the east end of the old, now filled in, James Bay. This site was recorded on the bases of a loose scatter of clam shell and dark soil in a flower bed near the front entrance of St. Anne’s Academy. When the site was recorded, I did not observe the usual Fire-broken rocks. Later, when extensive remodeling of the landscape was undertaken in this area, I observed that a large quantity of fill had been brought to this location and there was no evidence of an underlying shellmidden. Old water pipes were seen below the loose shell scatter. It was clear that soil containing shell was brought from somewhere else for the flower beds.

Figure 5, shows the location of the three sites mentioned above, placed on an 1862 map. DcRu-123 can be seen on a Peninsula, that is now mostly filled in on both sides. The historic Old Songhees Reserve, on the east side of Victoria Harbour, can be seen to the right of this. It shows where an inlet came into the reserve that is now filled-in along Harbour Road.

Historic Settlements

After the establishment of Fort Victoria in 1843, some of the Lekwungen, who had temporarily camped to the north of the Fort near the Johnson Street Ravine, were assisted in moving across the harbour in 1844, and later joined by many others. This settlement became a Songhees Reserve until it was exchanged for a location in Esquimalt Harbour in 1911, next to the Xwsepsum reserve. Another small village of four houses located just east of Laurel Point, was established and occupied by a mixture of local Xwsepsum, Lekwungun and Klallam people from Washington State (Keddie 2003; 2020)

The location on the historic Songhees village (the Old Songhees Reserve) above and west of Songhees Point was recorded as archaeological site DcRu-25. It has shellmidden that is very scattered, sporadic and mixed with historic refuse such as cow bones, iron fragments, glass and ceramic ware. In one location above the original rocky shoreline, where the shell seemed more concentrated, I found gun flints and older styles of pottery. Although I suspected the more concentrated shell layers are likely associated with the early 1840s occupation of the village, I collected charcoal for radio-carbon dating to determine if there may have been an older occupation of this area of the site.

I collected two charcoal samples from the same lower deposits that were exposed in a large bulldozer cut. The samples were one meter apart and .5m below the surface in similar looking deposits. The dated samples were 540+-75 years B.P. (SFU784) with a calibrated date of 543 B.P. or 1407 A.D. and 180+-75 years B.P. (SFU785) with a calibrated date of 197 B.P. or 1753 A.D. The considerable difference in the range of dates makes the results unreliable. I would interpret the more recent date to be closer to being accurate. However, both of the samples are likely from wood that was of considerable age when burnt. This area was heavily forested when occupied in 1844, and it is likely that older trees were consumed for fire wood at that time. Oil storage tanks were once stored at this location. Ground contamination of oil, which I observed, would have given an older date to a carbon sample.There are no artifacts from the site that would confirm a pre-1844 date. The few tradition tool forms of bone found at the site all show clear evidence of being manufactured with an iron rasp file and were found in contexts with European manufactured goods. Sandstone abrading stone were found, but would continue to be used to sharpen steel knives.

Historic Burial Sites

Historic burial sites were established at three locations in the Inner Harbor. These were at Laurel Point (Keddie 2019) and on the Coffin Islands and Colville Island (Keddie 2003).

Archaeological Sites of Selkirk Waters

There are three archaeological sites in Selkirk Waters. One is a known historic burial site DcRu-55, which I have described (Keddie 2024).

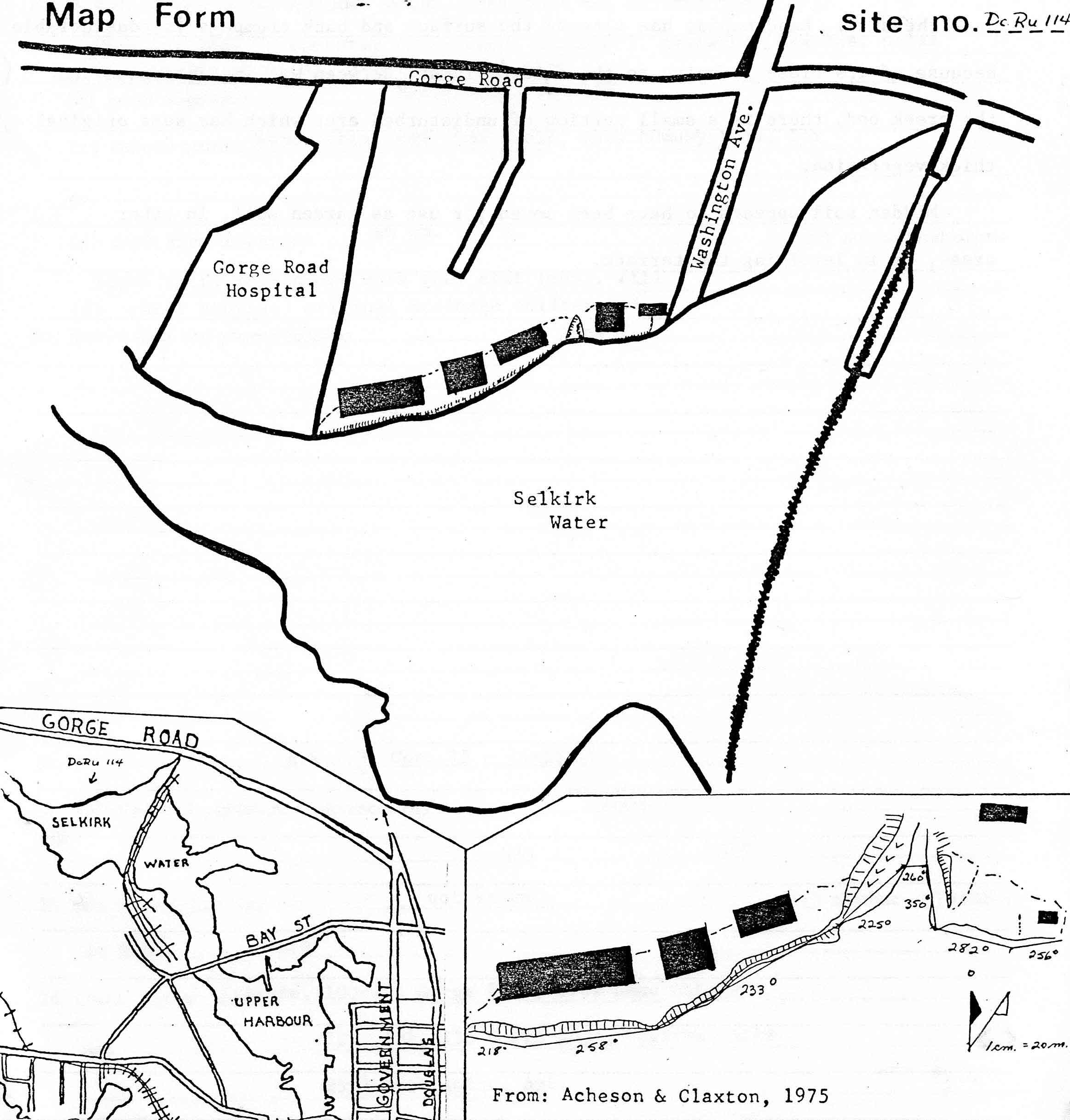

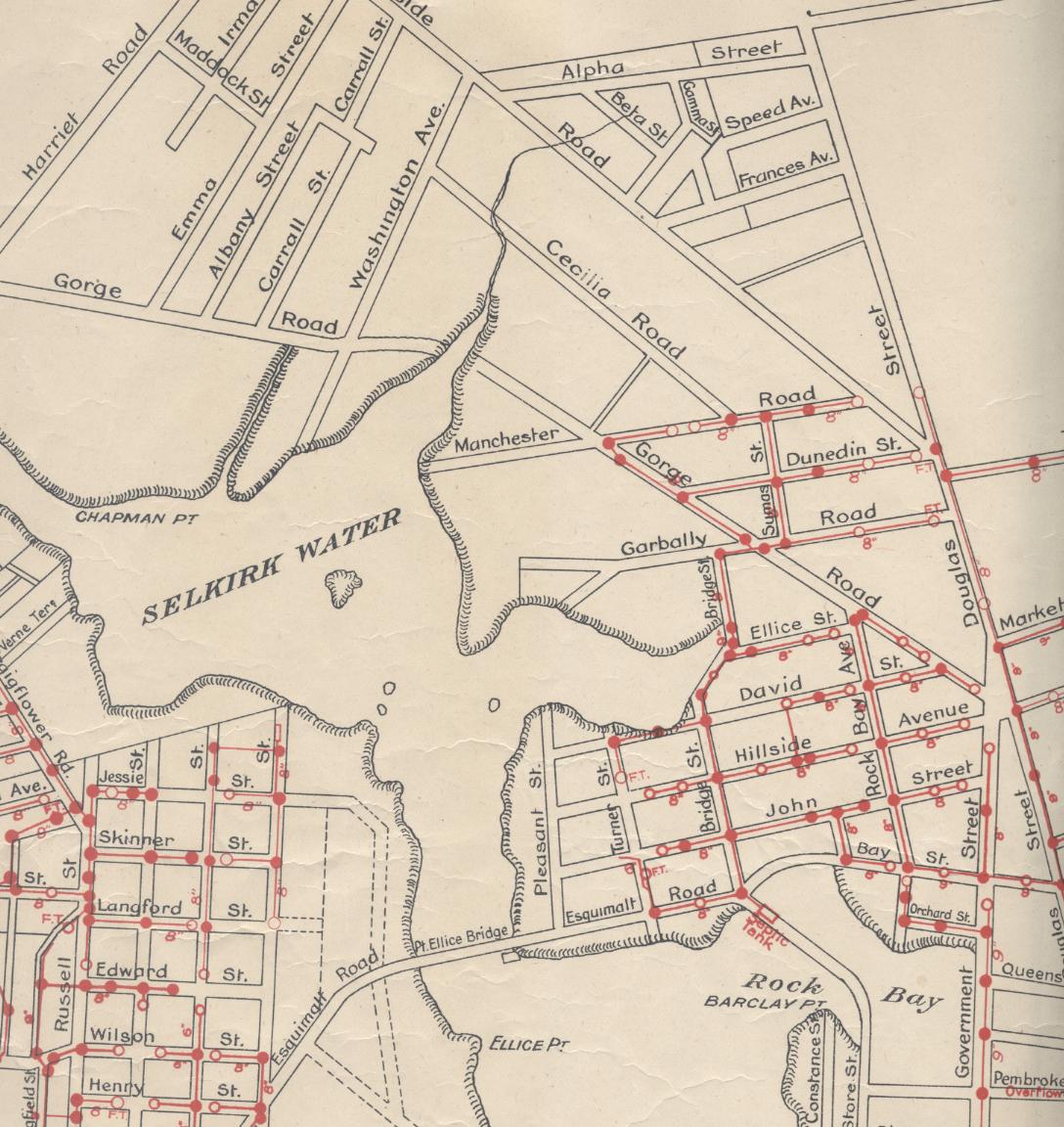

Two of the sites are shellmiddens. On the north side of Selkirk Waters between Cecelia Creek and Chapman Point and to the west of the pedestrian (old Railway) Bridge. is a large shellmidden site, DcRu-114. It extends along the waterfront for 220 meters, from the south end of Washington Street to the east side of the Gorge Hospital property. It once extended up to 22 meters from the shore and varied from 10cm to a maximum of 60cm in depth (Figure 6 & 7).

A small unnamed creek ran through the site, but the site was also on the west side of the Cecelia Creek. Much of it has been destroyed by apartment building. I observed intact midden in the exposed lower layers at the west end of this site. I extracted a charcoal sample from near the exposed bottom, 30cm below the then current surface. The radiocarbon date indicates that, at least, this part of the site was occupied 662 years ago or A.D. 1288. (SFU777. 670-+70; cal.662 B.P.).

There is no Indigenous stories or names that pertain to a Village or resource use at the Cecelia Creek location. There are no excavations that have documented the faunal remains at the site. However, given the size and depth of this site and its location, it may have been a winter village of a few houses at some time in the past as well as a seasonal resource site. Figure 8, shows the front of the site to the west of Washington Street. The old unnamed creek exist would be at the centre of the photo.

The site has a local source of year-round drinking water and fish and bird resources. In addition to seasonal fish runs of Salmon, herring and anchovies, there would be a variety of saltwater fish in Selkirk Waters. These would have included: shiner perch (Cymatogaster aggregata), striped seaperch (Embiotica lateralis), lingcod (Ophiodon elongates), kelp greenling (Hexagrammos decagrammus), saddleback gunnel (Pholis ornata) and various sculpin species.

Cecelia Creek would have had trout and have provided easy access to acquire inland plant and mammal resources in the Cecelia Creek watershed. Some of the local small beaches would have provided suitable sand and mud substrate in quit waters for bent nose clams (Macoma nasuta) and a few locations for the small blue mussel (Mytilus edulis. Although temperature and water salinity conditions are better for oysters (Ostrea lurida), further up the Gorge, there were likely available in a few areas of the lower Gorge waters.

The molluscs I observed in the exposed midden: Native Oyster (Ostrea lurida) were dominant. Native little neck (Protothaca staminea) and butter clams (Saxidomus gigantea) were common. Present, but not common, included Bent nose clam (Macoma nasuta). Horse clam (Tresus nutallii), Bay mussel (Mytilus edulis), California mussel (Mytilus californianus), Cockle (Clinacardium nutalli), Welk (Thias lamelloisa), barnacle and chiton. Live populations of Bent nose clam (Macoma nasuta) were observed on the small beach at the west end of the site and Introduced Japanese oyster were observed on the beach (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Bend nose clam beds on west side of DcRu-114. July 1992.

Crabs would have been common near the mouths of streams. The old James Bay was a location noted by the Songhees Jimmy Fraser as an important crabbing area and I have observed seagulls catching crabs in the upper harbour.

James Bay, now filled in by the Empress Hotel and Crystal Gardens, was a good location for harvesting crabs, but not for molluscs, as has been mistakenly reported in popular articles. During the large holes dug for the Convention Centre I did not observe any clam beds in the buried substrate. The more favourable species of clams, such as butter clam (Saxidomus gigantea) and Littleneck clams (Protothaca staminea), were available further away at places like Cordova and Cadboro Bay. These species are present in the ancient sites, but how common some of these species were in the Gorge Waters of the past is in need of further research. Much of the upper layer of deposits on the Gorge bottom are a result of historic disturbance activities over the last 150 years. The species that can survive in a few places today, may not have done so in the past.

Figure 10, shows the location of the unnamed creek at the site on a 1910 sewer map.

On the south side of the Selkirk Waters, at the Banfield Park Bay, is a small shallow midden, DcRu-109, extending along the bay at the east end of Banfield park, just before the land turns upward into a forested slope that extends below Catherine Street. The site is loosely scattered for about 155 meters along the shore and about 5 meters from the shore. The cultural material is mostly under about 6 cm in depth and contains only small amounts of fragmentary shell remains.

The area was once used as an animal pasture in the early 1900s. I lived close by and observed shore erosion and surface disturbance from tree falls, tree planting and deep tractor tires at this location numerous times over 40 years. I did not observe any pre-contact stone or bone material eroding from the site. I did, however, recover a broken arrowhead on the far west side of the Bay, which was not associated with any cultural deposits. I assigned the arrowhead to this site number, for convenance sake, so its location would not be lost. At that time single artifact finds were not given site designation numbers. This site location may be a temporary camp site used in the mid-19th century by northern Indigenous tribes that were referred to as camping up the Gorge (Keddie 2003).

Figure 11, shows the Bay at Banfield Park. The site, DcRu-109, is on the shore at the left portion of the bay. On the far right is where the Selkirk Waters end and a narrow part of the Gorge extends for 4 or 5 city blocks. The latter does not contain any archaeological sites.

Figure 11. Bamfield Park Bay.

References

Clague, J.J. 1983. Glacio-isostatic effects of the Cordilleran ice sheet, British Columbia, Canada. In Shorelines and Isostasy. Edited by D.E. Smith and A.G. Dawson. Academic Press, London, UK, pp. 321-343.

Keddie, Grant R. 2024. A lək̓ʷəŋən Burial Island. GrantKeddie.com https://grantkeddie.com/?s=Burial+site

Keddie, Grant R. 2019. Victoria Underwater. The Haultain Valley 14 meter Ocean Standstill. On-line Royal B.C, Museum web site, Curators Profile, January 17.

Keddie, Grant R. 2018. The Capital Iron Site, DcRu-116. Victoria Harbour. GrantKeddie.com https://grantkeddie.com/?s=Capital+Iron+site.

Keddie, Grant R. 2023a. The Lime Bay Indigenous Defensive Site. Grant Keddie.com https://grantkeddie.com/?s=Lime+Bay

Keddie, Grant R. 2023b. Indigenous use of Sling Stones in Warfare. Grant Keddie.com https://grantkeddie.com/?s=Sling+stones

Keddie, Grant R. 2017. A First Nations Shellmidden on Raymur Point, Victoria Harbour. GrantKeddie.com https://grantkeddie.com/?s=Raymur+Point

Keddie, Grant R. 2003. Songhees Pictorial. A History of the Songhees People 1791-1912, As Seen by Outsiders. Royal B.C. Museum, Victoria.

Keddie, Grant R. 1991. Spirited Divers and Spirited Diggers. The Midden. Publications of thee Archaeological Society of British Columbia. Vol. 23, No.3 June 1991. Cover & 6-7.

Keddie, Grant R. 2019. The Laurel Point Indigenous Burial Ground. RBCM Web Site, Curators Profile, July 12, 2019

Miskelly, Kristen Rhea. 2012. Vegetation and climate history of the Fraser Glaciation on southeastern Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada. Master of Science Thesis, Department of Biology. University of Victoria.