Preface

The Territory shared by Indigenous People in British Columbia, and far beyond, is the sky. A sky filled with sentient beings on the move and stories to tell. The sky is an interactive map that is constantly on the move. It is a domain of cultural knowledge.

For much of human existence people have seen the world of the sky as a reflection of their life on earth. It is obvious that the brightest stars and planets, and their movements, would become noticed. It is however, culture that blends them together, creating names and stories about what they are, and their relationships to each other. Celestial phenomena were incorporated into ritual, iconography, myth and shamanic activity. It is through cultures, the lights in the sky became the catalysts for the creation of philosophy, ethics and supernatural religions.

Humans have always patterned their world by observing the interaction of objects in the sky. We attribute cyclical renewal of birth, growth and death on earth to the celestial objects we observe in the sky. This has long been a key component of our process of adaptation and survival on this planet. When a musician today says “I want to be a star”, we tend to miss the hidden analogy.

Introduction

“The repeated cycles of the sun, moon, and stars helped to regulate human activity as people strove to make sense of their world and to keep their actions in harmony with the cosmos as they perceived it. In some cases, this was simply in order to maintain seasonal subsistence cycles; in others it helped to support dominant ideologies and complex social hierarchies” (Ruggles 2015).

As Haydon and Villeneuve’s study of 79 populations observed, almost all hunter-gatherers have some kind of astronomical system, but “simple foraging groups” do not usually determine precise specific days of solstices or equinoxes or hold special ceremonies to celebrate the solstices. With hunter-gatherers, it was the winter solstice that played an important role for ceremonies and feasting (Haydon and Villeneuve 2011:336).

In British Columbia, knowledge of astronomy appears to have once been more precise among Indigenous cultures than is usually reflected in the literature. Movements in the sky and movements on the earth were part of the same system of life. The order and events in the sky – seasonal cycles of the constellations, daily cycles of the sun and moon, and regular events such as the appearance of the Milky Way, rainbows, and meteorites brought about order on the lower levels of earth and could be appealed to for gaining special powers over the lives of individuals.

Everyone made observations of the skies to guide their seasonal and daily activities, and some cultures had specialists who made regular observations of particular constellations, stars and planets, as well as the dominance of the Sun and Moon. Regional differences in naming and stories about features of the sky suggest both long-distance connections as well as different traditions with separate origins.

Indigenous peoples believed that humans regularly interacted with the visible cosmos above. The sun, moon and stars were powerful supernatural agents of cyclical changes. Among speakers of the Salish languages of the southern coast, the “transformer” Hayls (Qäls with other names), and as Raven in the north, made most of the constellations. He transformed people and animals and placed them in the sky.

Stars are the spirits of all the people and animals that have ever lived on the earth. Comets and meteors are animate objects that can interact with people and are themselves seen as the spirits of important people.

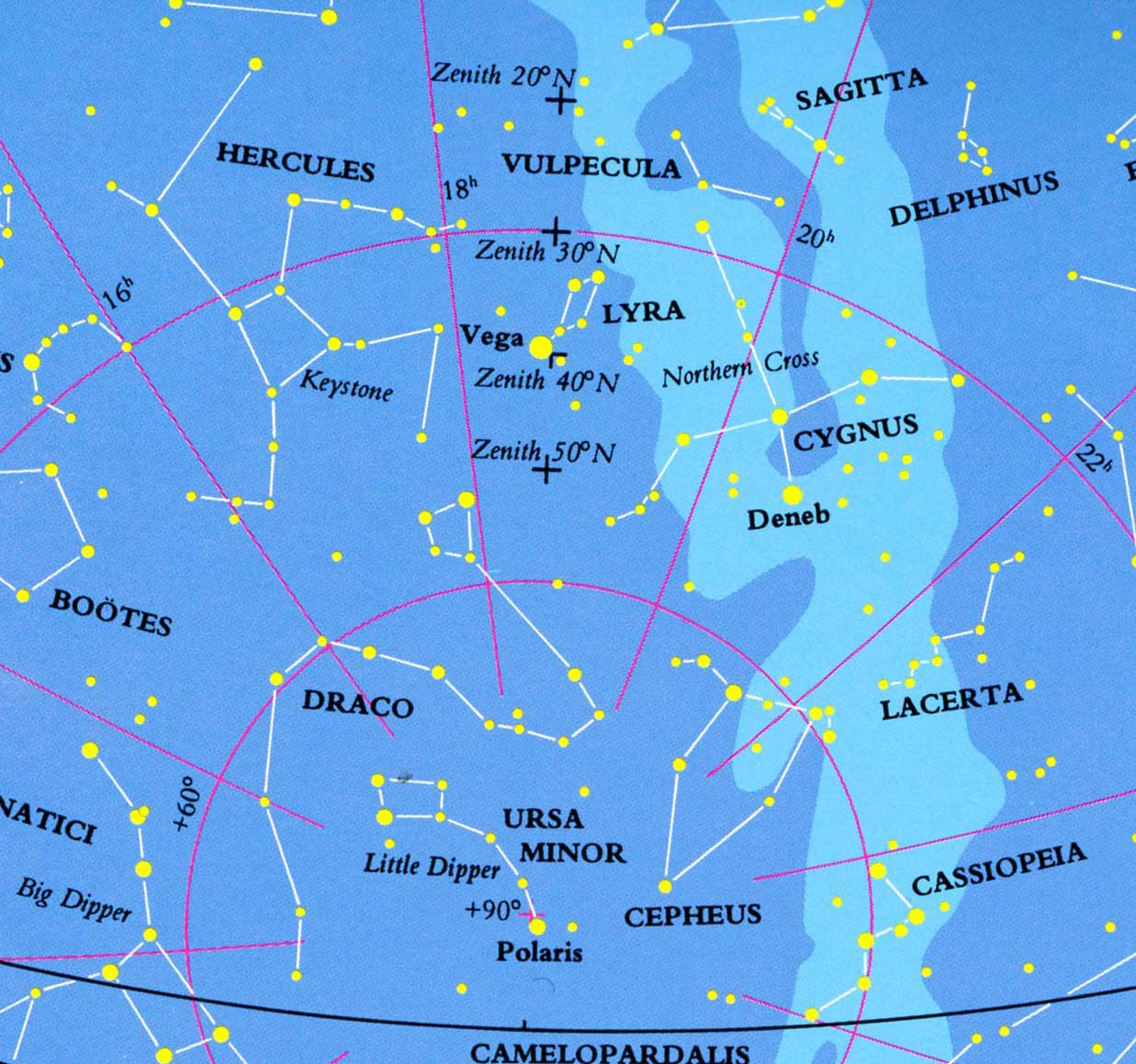

On the coast, the first rising of the Pleiades (Fig.1) after sunset marked the beginning of winter festivals. The Milky Way was seen as the place where the two parts of the sky meet – where the sun goes. It was the road of the dead; the upper portions being the place where those killed in battle went. Ursus Major or its small component, the Big Dipper, was the constellation of the northern sky – on the southern coast it was a transformed elk pursued by two men and a dog and in the southern Interior it was a grizzly or black bear pursued by three hunters. Ursus Major was linked with the world axis and the north celestial pole around which it turns.

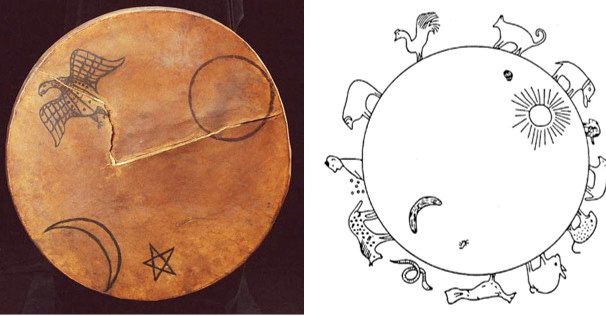

Images of the Milky Way, moon, sun and stars are represented on special dance regalia used in winter dance ceremonies on parts of the coast.

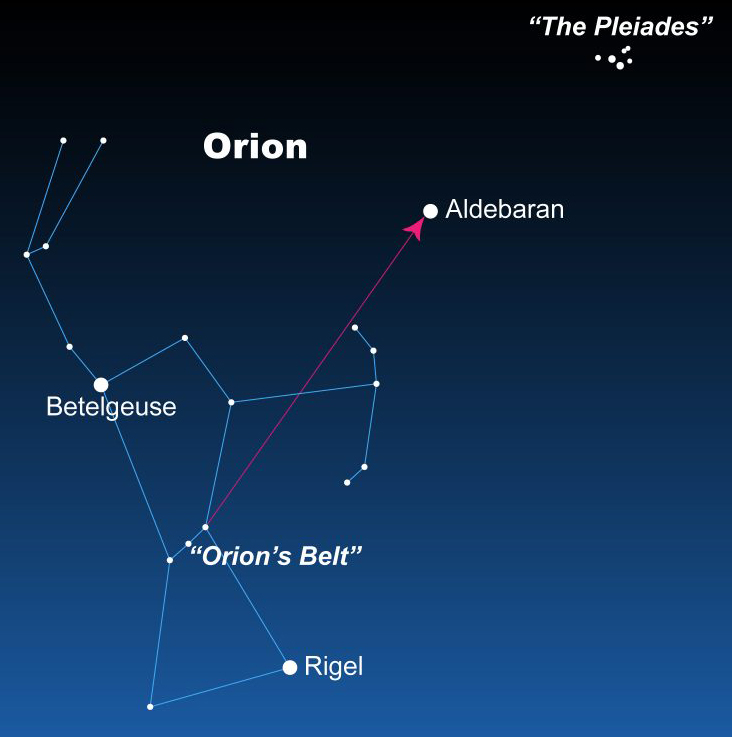

Aldebaran, the bright red star in Taurus is found in the widely distributed star husband stories, about two sisters who marry star men. Aldebaran first appears in the pre-dawn near the summer solstice. This star is called the sculpin or “little bullhead” – it comes in the morning telling fishermen that the fish are close to shore and can now be speared.

The Pleiades (Fig. 1) were seen on the southern coast as a group of children transformed by Hayls, the supernatural Transformer Being, when he found them crying for their absent parents or a group of seven women who were sitting round a pot of boiling grease. Orion was seen as big game hunters, or duck hunters, sea mammal hunters or fisherman in a canoe. Its bar of three stars was called “the bow”.

Only fragments of these once complex belief systems have been documented, but enough to show that Indigenous peoples of British Columbia had a much greater understanding of astronomy in the past than is usually attributed to them.

Images of what I see as stars and constellations on some ancient rock carvings remain to be studied to enhance our knowledge of Indigenous people and astronomy in British Columbia. The latter will include dating the astronomical inscriptions of star positioning on the rocks, that can now be reconstructed into the past based on the changing position of the Polar North star.

Constellation patterns changed in the past in relation to the polar star. Indigenous people saw different sky patterns 4000 years ago. The polar star was then seen as the star Thuban, in the constellation of Draco. Because the earth is not a perfect sphere, it bulges at the equator when the Sun and Moon exert a pull causing the earth to wobble on its axis. The Earth’s axial tilt is 23.4 degrees. The effect of this precession is seen in the change in the position of the pole star in relation to constellations.

The solstices, especially the winter solstice, were important for timing ceremonial events and the appearance of food resources. The solstice is the time at which the sun reaches its maximum or minimum height in the sky and is marked by the longest or shortest days of the year – About June 21 and December 22.

The winter solstice is the point when the sun, traveling across the sky, reaches its most northerly or highest point in the Northern Hemisphere, where it appears to “stand still” before beginning its slow shift southward.

Northwest coast cultures recognize the solstices, and have intercalary, ”between months” periods, to adjust for the months of the year and divide the year count in to a winter and summer series of months. Different tribal cultures carefully observe the solstices. The Kwakuitl, for example, name for the winter solstice means “split both ways” (Boas 1909:413).

As Cope indicates: “The general similarity in complicated ceremonialism, the means of sustenance, and other phases of culture throughout the Pacific coast, indicate that in the entire area economic conditions coupled with magico-religious beliefs are fundamental to the importance of the solstices.” (Cope 1919:142).

Problems with Recording the Information

There are numerous short descriptive comments on sky features, but only a limited number of these linked to stories on cosmology, obtained from Indigenous people in the last 150 years. The accuracy of what is being referred to in the sky by Indigenous consultants depends not just on their individual knowledge, but on the knowledge of Astronomy and the Indigenous language of the person recording the information, or the translator interpreting the language. Also, whether they were being instructed during the day or under the stars.

A European may ask an indigenous person about a specific constellation with which they are familiar, but in Indigenous tradition that constellation, as is the case in European and Asian tradition, may only be part of a larger set of stars that tell a different story. An excellent example of this is shown in the Northern Dene Constellations (Cannon 2025; Cannon et. al. 2020).

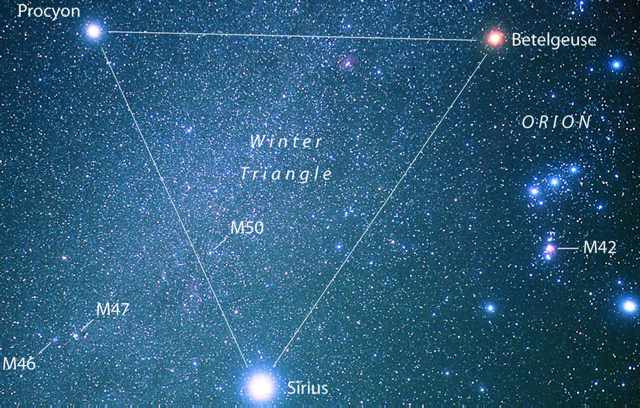

Most constellations we know today come from a second century catalog with 48 constellations. Many recent star clusters are called asterisms and are not officially constellations. Examples include the Big Dipper (called The Plough in Europe) and what is called the Winter Triangle. The Winter Triangle (Fig. 3) is an asterism formed from three of the brightest stars in the winter sky, that form an isosceles triangle. The defining stars are Sirius, Betelgeuse and Procyon the primary stars in the three constellations of Canus Major, Canus minor and Orion.

This could be confused with The Kite, a large asterism in the constellation of Boötes, visible in the northern hemisphere sky. The latter contains Arcturus, one of the brightest stars in the sky.

Sometimes the source of the Indigenous information is referenced as coming from, or pertaining to, a geographical region, a larger cultural community, language family or a specific population or family. Here, I may be specific where I can, but otherwise use the broader terms for a larger population. I have not taken the time here to get the Indigenous constellation names in their proper orthography. That will be better done by linguists working with Indigenous speakers.

Stories of astronomical features often extend beyond the boundaries of language and cultures. Some stories are ancient and have a basic theme that may be related to the economy, such as seeing Orion, Ursus major or Ursus minor (The Dippers) as relating to hunting activities during the hunting season. The animals hunted will be caribou, elk, deer or bear, depending on where those animals are an important part of the economy.

George Hunt’s Star Story.

Throughout human history the events of the sky are believed by many cultures to have a direct effect on their lives, and in some cases that humans can intervene to gain special powers, such as in the example, of the story below, told by Kwakwaka’wakw George Hunt.

The star clusters referred to in the story told by Hunt includes “a line of fire going from the kite to the seven stars”. The reference to the seven stars could be either Ursus Major (The Big Dipper) or the Pleiades. I have observed on several occasions, the Perseid meteor shower shoot like arrows across the bow of Orion toward the Pleiades.

The importance of this story is to show connections between the interlinked sky and earth. George Hunt dictated the story, when observing the Royal B.C. Museum artifact #1982 (Fig.4), which he referred to as: “Slave Killer used in Cannibal Dance”:

“Star Story of Quatsinox. Wahenox, a chief of the Quatsenox tribe, was out hunting sea-otter at the same time the Indians was expecting the star to spear at the seven stars, and as the night came on the Hunters camped at G’wal-emdres for the night of June and Wahenox kept awake and about past middle of the night he heard a sound as though the Heaven’s was splitting, and he looked up there, he saw a line of fire going from the kite to the seven stars, then he, Wahenox got up in a hurry and he took up his spear and he went and speared at a dead hair seal he had on the beach, and then he went up the beach and he lie down and went to sleep and while he slept he dreamt a man came to me and said ‘Wahenox, my friend you have done well, for you went and spear at that dead seal the same time I speared at the seven stars and now I give you my spear that never misses, and it will make you a wealthy chief and this my stone club whose name is lall-a-nala, this you will club the sea-otter with and also I will give you my name. Your name will be Elexweldzewe or ‘Stealthy Hunter of the Sky’ and then the star man disappeared and Wahenox waked up. He began to get an old man to hammer out a stone and made a Lak-anala like this and after this stone was finished Wahenox went out spearing and clubbing sea-otter and he came home with his canoe piled with sea otter.” (George Hunt, Sept. 1922:4)

Indigenous Astronomy

Here, I will put together a selection of the mostly European known stars, asterisms and constellations, and where possible, Indigenous meanings to the more commonly recognised objects in the sky, as recorded from Indigenous people in British Columbia and Northern Washington State. There are parallels to these beyond in all directions that would fill volumes. A few of these are mentioned.

“Most of the constellations were made by Qäls, who transformed men and transferred them to the sky” (Boas 1894:463). These usually involved individual or small clusters of stars. “There are very few transformations into constellations. These seem to be confined to the Upper Fraser River Delta. They are characteristic of the southeastern Salish tribes of the Columbia River, where they occur in the folk-lore of the Coeur d’ Alene” (Boas 1916).

Aboriginal Observers

There are many accounts of individuals such as: “Kookoo Sint, the man who studied the stars” among the Ktunaxa (Graham 1945:203) or a shaman who “predicts a lunar eclipse” among the Tlingit (Swanton 1909:66).

A more extensive account is provided by William Pierce who tells the story of Indigenous “astronomers”, in his recording of the Tradition of Andancaul:

“Andancaul is situated on the right bank of the Skeena River, almost five miles below Kitzeguela village. It was formerly a large fishing camp belonging to the Kit-wun-gah tribe. Behind this camp is a very high hill—the highest on the Skeena.

The name of this hill is Andimaul, meaning the “Seat of Native Astronomers.” The top of this hill was a specially selected place for the astronomers belonging to the different tribes to gather together on an evening watching the sun sinking away on the mountains.

By watching the sun in the spring of the year, and again in the fall, they claimed to be capable of discerning just what the coming season would bring forth. In the spring, they could tell whether berries were going to be plentiful or scarce, and whether there would be a good run of salmon or otherwise. Also, whether the summer would be hot or cold, wet or dry. In the fall, they knew what kind of winter to expect, whether severe or mild and whether a light or heavy fall of snow, also whether any epidemic would be prevalent.

One branch of the ‘Grease Trail’, extending from the Naas, led right past this seat on the hill, and along this route travelers were continually passing and repassing. Today any traveler passing by may see several little spots, here and there, which it is claimed to have been worn away from constant use as seats by these astronomers in the olden days. When sitting there in consultation and each one agreed, then a messenger was sent to all the different tribes warning the people and telling them what they might expect to happen.” (Pierce 1933:152-153).

McIlwraith also makes reference to a designated group of astronomer specialists:

“Moon, stars, and above all the sun, were, and still are to a certain extent, used by the Bella Coola in computing the passage of time. There are no individuals with the definite prerogative of keeping count of time, but formerly wise old men used to do so”. A Kimsquit consultant “stated that there were professional calendrical experts in his home when he was a young lad although members of the Kusiut Society sometimes attended to this mater” (McIlwraith 1948:1:27). The Kusiut Society’s designation is “The Supernatural” or “Learned,”. The word siut has both meanings. Members of the Society have names that are only used during special ceremonies (McIlwraith 1948:2:1).

McIlwraith wrote that: “The chief difficulty experienced by the Bella Coola in computing time rests on the fact that each month is judged by the moon, where as the main periods of the year depend upon the solstices. One old man, from whom much of the information was obtained, stated that trouble always came at the winter solstice when the month was divided into two sections” (McIlwraith 1948:1:26).

In describing a pictograph, ‘Nlaka’pamux, Annie Zedco York said: “Down below, you can see the Indian astronomers. They go to sleep outside and watch the stars. That the way they learn the moving of the stars. The arrow shows the evening star. That’s the star that can tell you the earth quake too. I relate everything with it. If I see that star, and the moon over there, racing with her, and she has a slight rainbow colour on her ring. I know there is going to be an earthquake. The bad weather the moon tells too” (York, Daly and Arnett 1993:186-7).

Olson recorded that in Quinault culture, that old men of the secret klokwalle society monitored the solstice by observing the sunrise and sunset, using a pole placed in the ground (Olson 1936:177).

Nuu-chah-nulth, Muchalat Harry, told anthropologist Phillip Drucker: “The men had places marked – they watched for star solstice in Dec. – axhumit yats kwistäs a’tic hüpat’s – it’s starting back. They watched for summer solstice ‘in hisit kamt’ too ”. He gave a name which referred to both the winter and summer solstice interpreted to mean “stops where always stops the sun”. Ahousaht consultant “aLiy û” gave the name “Te as simit” to the solstice moon (Drucker 1933).

Anthropologist Wayne Suttles indicated: “At Cowichan old men determined the winter solstice by lining up a stick or a tree with a distant mountain peak and observing the position of the rising sun” (Suttles 1955:87). James Point of the Musqueam said there was a: “weatherman who watched progression of the sun along the horizon at sunset and observed the solstices when the sun appeared to stand still or waver in the point at which it rises”. Suttle suggested that the name given to Mt. Baker that means “measure fish’ or “measure season”, “Seems to imply its use as a marker of the seasons”. The Musqueam noted in particular the constellation called bullhead, “probably the Plieades just before dawn” – to which Suttles adds, “The fish is probably the cabezon, a large species of sculpin. The constellation is often called ‘Little dipper’ in English” (Suttles 2004:518).

The Constellations and Asterisms

Pleiades

The appearance of the Pleiades (Fig. 1) was recognized as a main season indicator throughout North America. There is an element of confusion in which this constellation is referred to, as the “seven stars”. The name is used for both the Pleiades and Ursus Major (Big Dipper).

In Greek mythology, the Pleiades were the seven daughters of Atlas, a Titan who held up the sky, and the nymph Pleione, protectress of sailing.

In the old Druid rite of Britian, the Pleiades reaching its highest point in the sky at midnight, was believed to be the time where the thin veil dividing the living from the dead is thinnest. The modern-day festival of Halloween originates from an old Druid rite that coincided with the midnight culmination of the Pleiades cluster.

The Pleiades are located in what the Europeans call the constellation of Tauras, and are visible from almost every part of the globe. Aldebaran, called “the giant red star”. Is the “eye of Taurus”. There are over a thousand stars in the cluster, but only a small number can be seen with the naked eye. These are winter stars, visible in the Northern Hemisphere between October and April. Europeans referred to the cluster as the Seven Sisters.

The Nebra Sky Disc is believed to be an Early Bronze Age (c. 1800–1600 BC) artifact. It is one of the earliest European depictions of astronomical phenomena attributed to the Únětice culture. It features gold inlays for the sun or full moon, the crescent moon, among the 29 stars is a cluster of 7 that likely represent the Pleiades. Two arcs are suggested as representing solstices.

In Eastern Siberia this constellation is referred to as “the sieve” by three Koryak sub-groups, but one called it “wild reindeer” as was the same for Ursa major (Bogoras 1917:105).

On southern Vancouver Island, Lək̓ʷəŋən, James Fraser, told anthropologist Wilson Duff that the Pleiades were “7 stars” called “elk, kweaeis, boss of the deers up there” (Duff, 1952). Olson recorded the Pleiades as “Dipping Dipper” among the Quinault of Washington State. This could be viewed as being something similar to the term “sieve”. He added: “If a person can only see 4 or 5 stars, they will remain poor, but if they see 9 they will be rich and powerful” (Olson 1936:177).

Boas recorded that the Pleiades: “were children whom Qals (or Häls) met when they were crying for their absent parents.” The transformer Hayls, threw them into the sky (Boas 1894:463; Boas 1916:604; Bouchard and Kennedy 2002:95). Their importance can be seen in the recordings of Leslie Spier among the Klallam: “The Pleiades called End-ando’ksai, are a group of little children who announce the dawn when they first appear on the morning horizon” (Spier 1930:231).

On the lower Fraser River, the Sardis, saw the Pleiades as: “7 women were sitting round a pot of boiling grease were changed to these stars.” (Jenness 1934-36).

Klallam saw: “The Pleiades, s’ho’-dai, represent toad-fish” (Gibbs 1877). This fish is the Plain fin midshipman (Porichthys notatus). Tomo, Brown’s main Indigenous consultants for southern Vancouver Island referred to the Pleiades as a “collection of fishes” which fits with him calling the handle of the Big Dipper as “two men in a canoe” – as they were likely fishing. The four stars of the upper Dipper are “elk”, which suggests that some Indigenous people saw two components of what Europeans called the Dipper.

On the northern coast, among the Tlingit, the Pleiades is the: “Principal Sculpin”. (Swanton 1909:107). In a Tlingit story of “an encounter between Sculpin and “Yulth (Crow)” about who was the oldest, Yulth said: “I want you to be next to me. There will be many sculpins, but you will be the head one. So mighty crow threw sculpin up into the sky, where he is now seen (the Pleiades or the big dipper).” It is most likely this is Pleiades that represents a cluster of fish.”

The Haida saw the Pleiades as a canoe “water bailor” (Hill-Tout, 1903:57). Among the Kwakuitl, Pleiades is the: “Sea Otter which is dragging the Orion hunters” or “a sea hunter with Orion, chasing a sea otter with a fire-ball on its head (Boas 1935:94).

In the Interior the: “Pleiades: – sem-il-nu. The word for Pleiades means star island, and the il in its connecting part is merely euphonic, the sequence of three consonantal sounds such as those expressed by min being something unheard of in the Carrier language.” (Morice, 1932:94). “The Sta-tlum-ooh (Lillooets) [St’ãt’imc] call the Pleiades in-mox, meaning the “bunch” or “cluster” (Dawson 1892:89). With the Nlaka’pamux, the Pleiades are also “called ‘bunch’ or ‘cluster.’ They are the friends of the Moon. The Indians used to tell the time of night by them, reckoning by their position in the sky. The star that follows the Pleiades is called ‘the dog following on their trail’.” (Teit 1900:340-341).

I would suggest that the latter “dog” star is Aldebaran, a bright red giant star representing the eye of Taurus in the neighbouring constellation. The name Aldebaran is from the Arabic for “the follower”. Usually perceived as following a herd of animals, as represented in the Pleiades cluster.

In the Francois Lake area of Fort Fraser, caribou “called Sum-ni-tan-li” are the animals of the Pleiades cluster (Dawson 1876:185). Jenness records “Caribou” for the general name of the Pleiades among the Carrier People (Jenness 1934:140).

Among the Secwépemc: “The Pleiades are called by the Shoo-wha-pa-mooh “hu-ha-oos”, or “the bunch”, and also kul-kul-sta-lim, or “people roasting”. The last name is given from a story of their origin, which relates that a number of women who were baking roots in a hole in the ground, as is their fashion, became changed into this group of stars” (Dawson 1892:39). After referring to the bears and hunters of the Ursa Major, among the Nlaka’pamux (Thompson), Teit adds a reference to other stars called: “women engaged in roasting roots” (Teit, 1900:341-342). It is likely that this is similar to the story recorded by Dawson.

Among the “Athapaskan” the Pleiades are “five racoon children, the small red one being Coyote’s child” (Barbeau 1915:221).

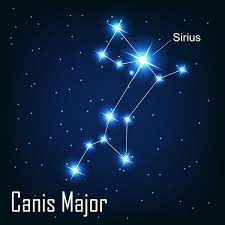

Orion

The constellation of Orion is made up of three dominant stars, Anitak, Alnilam and Mintaka, often called the hunter’s belt (Fig.6). This set of stars is prominent during winter in the northern hemisphere. In European and Asian myths, Orion was a powerful hunter placed in the sky, hunting animals, with his dogs represented by Canis Major in the constellation Sirius, the brightest in the night sky, and the star Procyon, in the small constellation of Canis Minor, located a little to the north east of Canis Major.

Among the Sami of Finland they believed they were “descendants of the Sun. The Sun’s daughter gave the Sami their reindeer, allowing them to wonder along the Sun beams down to earth”. The Sun’s son married a Giants daughter to create the Gallabartnit people “who were such accomplished hunters and skiers that, when they died, the Sami raised them to heaven instead of burying them in the traditional way. Today they form the constellation Orion’s belt (The skiers)”. (Gaski 2004)

Like some Indigenous stories, in British Columba, Orion represents hunters or a hunters bow and the animals hunted are represented by the nearby Pleiades star cluster. Sometimes fishers are represented instead of hunters and the Pleiades as fish.

On the southern coast Orion is connected with stories of duck hunting and fishing, Among the Saanich, Orion was “a bow and arrow”. “Orion’s belt, which they imagined were six men in two canoes hunting duck was papayahtil” (Jenness c. 1934-36). Lekwungen, James Fraser saw Orion as: “3 stars straight. 3 Indians hunting ducks. Bow man spearing. Other 2 paddle” (Duff, 1952). Among the Sooke: “They have names for several of the principal constellations calling the belt of Orion “The bow” (Grant 1849).

Gibbs, working in northern Washington State, referred to the “Salish” in general notes: “The belt and sword of Orion, le-li’-yi-was. They represent three men taking fish.” (Gibbs 1877). Quinault, Lucullus McWhorter, told a story from the Hood River area, about Orion, in which Clark summarised the stars configuration: “In the sky are two canoes pointing toward a small star, which is a fish. Each canoe is made up of three canoes. The three stars above, closer to the snow land, are the cold wind brothers. The three stars below, closer to the warm land, are the chinook Wind brothers. The little star is a salmon floating in a Big River. The canoe men are racing for it. The Chinook Wind brothers are winning the race.” (Clark 1957:156).

Orion in the Interior

Among the Secwepemc: “The stars of Orion’s belt are named kut-a-kekl’-la, or fishing” (Dawson 1892:890 & 39).

To the Nlaka’pamux (Thompson) Orion’s belt is: “Bark Canoe” and “Canoe with men in it” (Teit 1930:179). After referring to the bears and hunters of the Ursa Major, Teit adds: Another star is called the ‘swan’. Others behind it are called the ‘canoe’. The latter was said to be filled with hunters in pursuit of the swan. Still others are called ‘women engaged in roasting roots’, ‘fisherman fishing with hook and line’, ‘weasel’s tracks’, ‘arrows slung on the body’. These are said to have been a hunter carrying his bows and arrows” (Teit, 1900:341-342). It is likely that the hunters and fishers referred to here are in reference to the three stars of Orion.

The “constellation of Orion – Enite. As to the expression by which Orion is designated, it refers to a beautiful legend according to which three brother huntsmen were raised up to the sky while pursuing (enitel) a flock of caribou, later changed into a cluster of stars (semilnu) the Pleiades” (Morice, 1932:64-65).

Orion on the Central and Northern Coast

The Haida see the: “Belt of Orion is the “roasting stick: of upset canoe” (Swanton 1905:12). The Kwakuitl saw the: “Sea Otter hunter(s) being dragged by the Pleiades Sea Otter (Boas 1935); A seal hunter with his crew (Boas and Hunt 1905:383-4).’ Linked to a story involving Orion men and village (Boas 1910) and referred to as

“Harpooner of Heaven”, “Place of paddling” or looks like a ladder (Boas 1905:383).

To the Tlingit, a story refers to how Raven transformed men to the stars who won’t ferry him into “the halibut Fishers”. (Swanton 1908:107).

Among the Chukehee and Kamchatcan Peninsula Koryak, Orion is mostly “the crooked star” or “crocked one”, but among the Koryak of Qare’nin it is also named “crosswise-bow carrier”. In the latter populations the belt of Orion can have separate names. Two sub groups naming the belt “crosswise-bow carrier”. One Koryak group calling it “handle of scrapper” and the Kamchadal naming it “long scraper”. (Bogoras 1917:105).

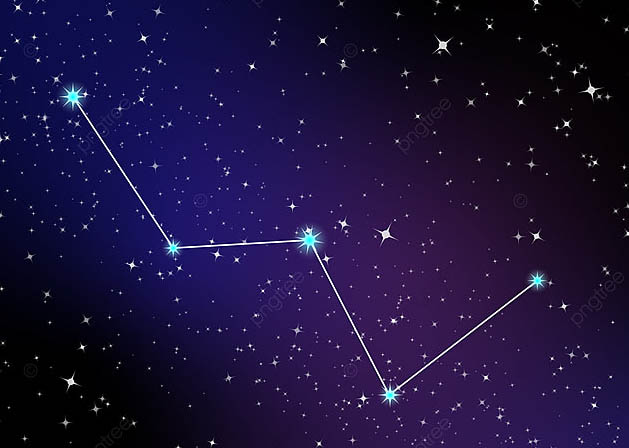

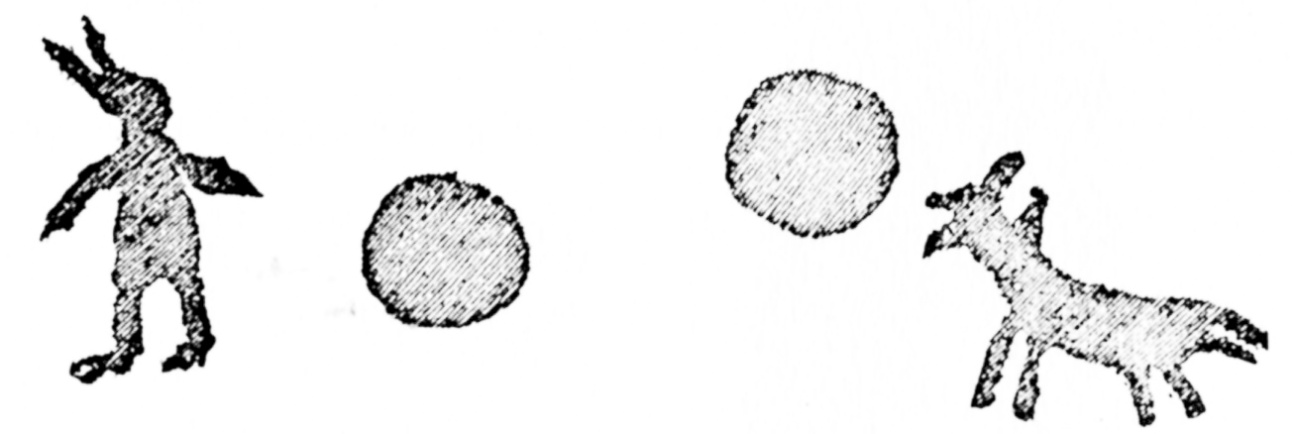

Ursa Major or the Big Dipper

In the southern Interior Ursa Major (Fig.2 and Fig.7) is most closely related to stories of hunters with dogs pursuing bears. The four stars of the bowl of the dipper are bears and the handle of the dipper the hunters or their dogs. The hunter’s theme is also used by the Koryak and Kamchadal of Eastern Siberia, however, as expected, they have various names that refer to “wild reindeer star” or Wild reindeer bucks” (Bogoras 1917:104).

In regard to the carrier: “It must be noted that the names of constellations (sem-lge-etli, stars that belong to one another), animals or trees are personified. Therefore, if we speak of Yihta (Ursa major), for instance, as of a human being, as is the case in an apologue well known to the Carriers, we must, when occasion requires it, use the verbs of locomotion with the ending proper to those the subject of which is a person.” (Morice 1932:87;95). Maxine George of Fort Fraser said her people called the Big Dipper “Ya Da” (Duff 1951).

Dawson indicates that: “The four stars which form the quadrilateral of the Great Bear are, singularly enough, known to the Shuswaps as the bear stars, kum-a-koo-sas’-ka. The three following large stars are three brothers in pursuit of the bear. The first hunter is brave and near the bear, the second leads a dog (the small companion star), the third is afraid and hangs far back” (Dawson 1892:89).

A longer version of this story was recorded by Teit among the Nlaka’pamux: “The Great Bear or Dipper is called ‘Grizzly Bear’. The three stars of the handle of the Dipper are said to be three hunters in pursuit of the bear. The first one was brave and fleet of foot, and fast gaining on the bear. The second was slower, and leading a dog, the small companion star. The third was afraid, and not very anxious to overtake the bear. They were all in this position when turned into stars. …The Lower Thompson believe the Dipper to be the Transformers, the children of the Black Bear turned into stars (Teit, 1900:341-342).

In regard to the Tahltan, Teit records: “The Dipper is watched during an eclipse to keep confidence”. If the dipper were to disappear at any time it is a catastrophe.

To the Carrier: “The bowl is four brothers, the bright star between them and the Pleiades is their dog-sister (Capella?)” (Jenness 1934).

Morice suggested that Ursa Major was represented in a Pictograph located halfway between Fort St. James and Pintce: “The Natives are not agreed to the meaning of the large spider-like figure to the left, but the probability is that it is intended to represent Yihta, the Great Bear.” (Morice 1894:206-207).

A Chilcotin story: “Yitai (The Great Bear) and the Hunter. Man goes to hunt. Waits for Yitai, the seven stars to appear, soon dogs start a bear. Hunter pursues, and comes to a man sitting on a log. This man is Yitai, who had taken form of bear, and then of a man. Has blanket of skins of all kinds. Tells hunter to choose skins of whatever animals he most wishes to kill. Hunter chooses bear, marten, and fisher. After that, when he goes to hunt, he always takes a bit of skin with him, and is always successful. Yital returns to sky.” (Farrand 1900).

Older Koyukon people can tell the time of night by observing the Big Dipper’s location in the sky and the handles angle to the horizon. In mid-winter nosikghaltaala’s head points toward the place of sunrise just before twilight begins. Jette heard people announce that it was time to get up by saying, ‘The Big Dipper has turned his head to the light’. He also describes marking time by the course of the moon when it is present and by watching several other stars or constellations, including Altair, Cassiopea, the Pleiades, and Orion’s belt”. (Nelson 1983:39).

The best explanation of the importance of Ursa Major was provided by Koyukon (Ten’a) Indigenous consultants to Frair Julius Jetté. He acquired information from elders that lived a more traditional life. This would be relevant to large areas of British Columbia. Jetté was a Canadian Jesuit priest, missionary, and ethnographer of the Koyukon people. He lived in Alaska working with Indigenous people for 30 years. He was trained in linguistics and was fluent in Dene languages and five others (Laugrand 2003; Jones 2000). See Appendix 2.

On the Time-Reckoning of the Ten’a. From the Notes of Friar Julius Jetté.

In the Interior, the St’át’imc of the Lillooet region noted: “the Great Bear me-hatl, the name of the black bear” (Dawson 1892:89). The Ktunaxa of the Kootenay region saw Ursa major as: “Grizzley bear. Tied to a stake at Polaris, revolving around it and being observed at night to tell the time” (Turney-High 1941)

The Southern Coast Traditions of Orion

On the Gulf of Georgia and Fraser River: “A elk pursued by a man and a dog is transformed into the Dipper” (Boas 1916).

Boas recorded: “In a village below Yale on the lower Fraser River, a boy who constantly tormented his mother for more food had a visit from the sun who came in the shape of a man and said: “I am the sun, the moon is my brother, and the bright star often seen close to the moon is his wife” [Venus]. “Once he went to hunt moose. He led his dog on a rope and went upriver. When he spied a moose, he let loose the dog, who pursued it along the edge of the water. Just then Qals passed by and transformed the young man and the dog into rocks. He took the moose and flung it into the sky, whereupon it was transformed into the four brightest stars of the Big Dipper (Boas 1891-95, In: Bouchard and Kennedy, 2002). It is likely that the term “moose” here is wrong, and the reference was to elk, which is what moose are called by some in Europe. Moose did not come into southern B.C. until after 1908.

“The Great Bear, kwa’-gwitsh (the elk). The four stars which form the animal are followed by three Indians and a dog.” (Gibbs 1877). Swan also refers to this as “Elk” in regard to Puget Sound (Swan 1870). The Couer D’Alene saw “Three brothers’ and their “Bear” brother-in-law (Boas 1898:125).

In a Quinault story of “The Earth People Visit the Sky People”, a group of people, in human and animal form, climbed up a string of arrows to rescue two girls. Skate did not return: “Skate is still up in the sky. He is the big dipper.” (Clark 1953:160). The Quinault saw the stars of the Dipper handle as three hunters (Olson 1936).

To the Klikatats in the Mt. St. Helens area of Washington State, in 1853-4, the Great Bear “Spilyeh” was the wolf. (Gibbs 1967:13).

Jenness notes that among the Sardis on the lower Fraser River the “Dipper: keye’itc: elk.” And among the Saanich “they called the Great Dipper the elk” (Jenness 1934-36).

The Northern Coast Traditions of Orion

The Haida saw the Dipper as: “skin board of upset canoe” (Swanton 1905:12) and “Sea otter [skin] stretcher” (1903:57). Swanton noted: “Ursa Major, the Big Dipper, was by far the most important – even the name (nosikghaltaala), ‘it rotates its body’, refers to the calculable circle it makes in the sky. In the day time nosikghaltaala was a man. After a violent quarrel with Raven, his spirit went up into the sky to become the measure of time. As he appears now, the dipper’s handle is his back, its last star his head, and the two outer stars of its bowl are his buttocks (Swanton (1905:12).

It was noted for both the Tsimshian and Taltan as the “Dipper” (Gibbon 1964).

By the Tlingit as Ursus. “Bear” (Hagar 1900). The Tlingit had the Constellation carved on mortuary Pole (Barbeau 1964). Boas gives the Tsimshian names that include: “Kite”, “Dipper”, “Halibut fishing line”, “Canoe Stern board” and “Old bark box”, but it is unclear if these terms all refer to Ursa Major (Boas 1909:454).

The Ursa Minor (Little Dipper) Constellation

The north star Polaris is at the tip of the Ursa Minor (Fig.7). Most cultures recognized the geomagnetic polar or north star as standing still in relation of its neighbouring sky features. Today, of course, we know that it can move around the general area, in relation to the earth, as much as 700 miles in a century,

In the southern Interior the: “Polar star. sem-lis.al, star that does not move.” (Morice 1932:76). The Quinault believed: “Polaris is a dog who is with three hunters.” (Olson 1936:178). The hunters here would be the stars forming the handle of the little dipper.

Sculpin Constellation

Lekwungun, James Fraser provides: “sxwe’net – bullhead star. This star comes in the morning. That’s the time the fish come close to shore, can spear fish close to shore. Indians wait for that star 2-3 months …This star comes once a year – summertime” (Duff field Notes 1952 – Dec. 18).

This is the same as the SENĆOŦEN name, SX̱ÁNEȽ (the Bullhead Moon), was an annual event recognized by the W̱SÁNEĆ people of Vancouver Island. The event is typically associated with the time of year when large bullheads (a type of sculpin fish) appear along the shore around April (see Montler 1991:12]. Jennes noted the Saanich called: “The little dipper, the bullhead” (Jenness 1934-36).

This asterism is within the head part of the constellation of Taurus, best viewed in in the northern sky in Winter. Included in the Sculpin is the bright red star Aldebaran seen in European tradition as the bull’s eye.

There is no star that comes once a year, so the above statement of Jennes may refer to the helical rising when a star becomes visible in the pre-dawn sky for the first time in a year after becoming obscured by the sun’s glare. This marks the start of the year.

Hyades Constellation

Like the Sculpin asterism, Hyades is also in the head portion of the constellation Taurus. Among some Salish speakers, the Hyades is “a scraper of mats”. The Haida see it as the “sternboard” or “footboard” of a boat (Dawson, George M. 1892:57).

Canis Major Constellation

Sirius is the brightest star in the constellation of Canis Major (Fig. 8). Sirius, among the Dene is the “Sun’s dog” (McKenzie Delta Research Project. Vol. 2:81). In Greek mythology Sirius is often depicted as the bigger of the hunting dogs of Orion the hunter. The constellation of Canis Major was not recognized only the bright Sirius.

Auriga Constellation.

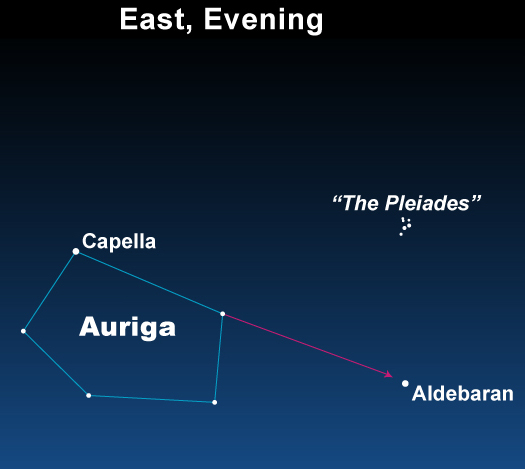

To the Nlaka’pamux (Thompson) Interior Salish speakers, Auriga is: “a group of women cooking roots, a skunk is trying to get among them (Teit 1930:179; Boas 1898:125). To the Klamath of California Auriga, is “followed by Rabbit (Kai)” (Speir 1930:221). The skunk, rabbit or hare. may pertain to The Pleiades or Aldebaran. Capella, is the brightest star in the constellation Auriga and the sixth-brightest star in the night sky, and a prominent sight in the northeastern sky during autumn evenings (Fig.9). This bright star twinkles red and green flashes low in the northeastern part of the sky in the early evening.

Cygnus Constellation

James Teit notes the similar naming of Cygnus (Fig. 10), by the Couer d’alene of Washington State: “A snow goose with spread wings on a lake” and for the Nlapa’pumux: “A lake with a swan on it” (Teit 1930:179). The bright star Deneb is probably the bird.

Cassiopeia Constellation

A prominent constellation in the northern sky in the shape of a “W” or “M” formed by its five brightest stars: Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta and Epsilon Cassiopeiae (Fig.11).

To the Interior Carrier: “Cassiopeia is a frame used to stretch an elk skin. The stars are the stakes”. (Adamson 1933:325). Clark records a story about four brothers that went out elk hunting near Lapush Washington. They were killed by a supernatural man who turned into an elk. A fifth brother, Toscobuk, shot the transformed elk. He skinned it, but found it was too big: “So he threw the elk skin up to the sky. You can see it any clear night. Stars mark the holes where Toscobuk drove the stakes when he was stretching the skin. Other stars mark the elk’s tail.” (Clark 1953:157).

The Koryak sub-groups of Eastern Siberia have names meaning “small reindeer buck” and “group pf women”.

Planets

There are five planets visible with the naked eye. Jupiter, Mars, Saturn, Venus and Mercury. The latter two are morning stars in September.

The stories of two women who come to live with male stars or planets is wide spread in North America. In the Lekwungen story The Wives of the Stars: Two daughters of a “chief” – “lay down among the trees and looked at the stars. The elder sister said, “I wish the big star up there (Jupiter) would be my husband.” And the younger one said, “I wish the red star there (Mars) would be my husband.” Then they fell asleep. When they awoke, they found themselves in a strange land. The stars had taken them into the sky. Now they saw that the stars were men. …The stars became their husbands.” (Bouchard & Kennedy 2002:171). Boas thought the location might be Observatory Hill in Victoria and indicates: “Exactly the same story is told in Nova Scotia”.

Boas, in reference to the Comox, states: “Mars is the younger red star and Jupiter the old bright-eyed star in the Star Husband stories. (Boas 1895:64).

In a similar story recorded in the 1860s, the stars were Aldebaran and Sirius. The story involves the creation of Knochan Hill in Saanich. In the story, two Lekwungun girls: “were gathering gamass, [camass] at Stummas (near Elk Lake. Vancouver Island), and after the manner of the gamass-gatherers they camped on the ground during the season. One night they lay awake, looking up at the bright stars overhead, thinking of their lovers, and such things as girls Indian or English, will talk about. The Indians suppose the stars to be little people, and the region they live in to be much the same as this world down below.

As one of the girls looked up at the little people twinkling overhead, one said to the other looking at Aldebaran, the red eye of the Bull. ‘That’s the little man to my liking; how I would like him for my lover’. ‘No” said the other, ‘I do not think I should; he’s to glaring and angry-looking for me’. ‘I am afraid he would whip me. I would better like, that pale-looking star, not far from him. And so, the gamass-gatherers of Stummas talked until they fell asleep. But as they slumbered under the tall pines, Aldebaran and Sirius took pity on their lovers and came down to earth, and when the girls awoke in the morning it was in Starland, with their lovers by their sides. In the country up in the sky. For a while all went well and happily, until after a while …they wearied to see their friends at Quongsung (‘The Gorge’ in the Victoria Arm) and Cheeulth (Esquimalt) [Esquimalt], and their gentle husbands grew sad at heir melancholy wives” (Brown 1989:179-180).

This long story continues, where the two girls make a large rope to get back home through the sky hole, while their husbands slept. The rope was not quite long enough but the Satitz,, the East wind, “took pity on them, on them and blew them toward the earth where they landed “near the valley of the Colquitz – not far from their home – with the rope lying beside them. So they coiled it up, and Haelse make it into a hill [Knockan Hill] as a monument, to remind the mortals not to weary for what is not their lot. And after this the girls went back to Quonsong, and became great medicine-women, but remained single, all for love of ‘the little people’ above.

The stars, however, are gentle little folks, and were not at all angry with their wandering brides, and used often to visit them on earth again, when Sean Seakum (my lord the sun) has ended his travels over the great plain of the earth, for ‘see ‘seam, my informant, told me, ‘don’t you often see at night the stars coming to earth’ and as he referred to the ‘falling stars’ (Brown 1989:179-180).

The star Aldebaran is the “eye of Taurus” and is called “the giant red star”. This may be confused with the planet of Mars, referred to as “a small red star”. In a Sarcee tale, “The Bride of the Evening Star” a young girl said: “I wish that beautiful star were my husband”. She ended up in the sky. But returned on a rope made of strips of buffalo hides. (Jennes 1956:33-34).

In a Chilcotin story: “The Two Sisters and the Stars. Two sisters sleeping out at night, see two stars. One large one and one small, and wish for them. Toward morning find two men sleeping with them. The men are the two stars. The older sister has the big star, who is an old, blind, and decrepit man, while the younger has the small star, who is young and handsome. They try to escape the old man who follows them. Finally, the sisters, after several adventures, overcome him by strategy” (Farrand 1900).

A similar story was told by the Quinault: “Once Ravens two daughters went out on the prairie to dig roots, and night came on before they knew it, so they had to camp out where they were. And as they lay talking under the open sky, they came to speak of the stars; and the younger girl said, “I wish I were there with that big bright star!” and the older said “I wish I were there with the little star”. Soon they fell asleep, and when they waked they found they found they were up in the sky country, where the stars are; and the younger girl found that her star was a feeble, old man, while the older sister’s star was a young man” (Farrand 1902:107-109). This was a very long story, where the younger girl tried to get to earth on a rope being made by spider. She chose to go when the rope was not long enough and died dangling in the air above her father’s home. The Raven gathered all the people and animals to attack the sky to get back the other daughter

A bird lowered the sky and a special bow was made. Wren shot arrow after arrow which formed a chain to the sky for the attackers to climb. What followed was exchanges between animals that created their attributes. The sky people beat them back, but they escaped with the other daughter of Raven. Some of those that retreated did not make it back and can be seen now in the stars.

Venus. Morning Star/ Evening Star

The planet Venus, due to its exceptional brightness and position in the solar system, is known as both the morning and evening star. It appears on the eastern horizon early in the morning before dawn and in the evening after sunset.

To the Quinalt. “Star of Daylight”. “The evening star is the chief or head tender of all the other stars.” (Olson 1936:177). “The evening star, klah-hil-lal-lus (twilight or dark has come)”. “To be the moon’s youngest brother and always follows it; and the morning star, Le-heh-lel-lus, day light has come to bear the same relation to the Sun”. (Gibbs 1955:318-321; 1877).

Jennes wrote: “Evening (Morning? star): brightest white star in sky, with a very tiny star beside it. Two girls were lying out looking at the stars. One said isn’t that red star beautiful. I would like to have it as my husband. The younger said “I would like to have the brightest star. When they woke up two men were sitting behind them. They said “How would you like to go up to the sky with us?”. The older sister said “I don’t want to go with you”. The younger said “I will go with you”. So now you see the two sisters in the sky.” (Jenness c.1934-36). The tiny red star here is likely Mars.

Venus In the Interior

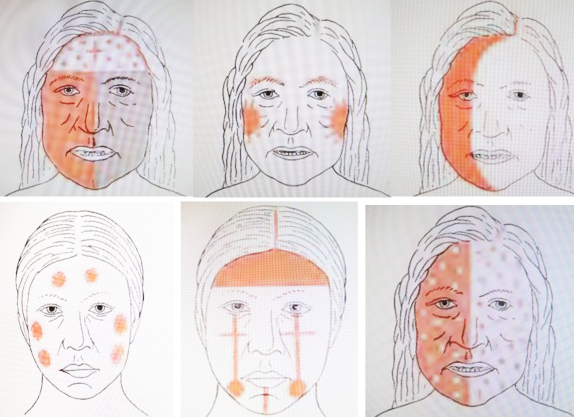

“The Morning Star is called ‘the bright face’ or ‘bringing in the daybreak’ (Teit, 1900:341). Teit shows a tattoo of a Lillooet shaman with “morning star”, in his figure 100h (Fig. 12). To the Secwepemc (Shuswap), “The morning star is named chi-whi-looh-tan’, or “coming with the daylight”. Also, wo-pk-a, or “one with hair standing out round his head.” (Dawson 1892:89).

Among the Ktunaxa (Kutenai), Venus is: “Observed to determine the time before daylight” (Turney-High 1941). The Carrier saw Venus as: “star (morning), ukwe-yelkhaih, on it daylight comes.” (Morice 1932:85). The Dene of the Mckenzie Delta: “Star of the Tall Women”.

Venus on the Northern Coast

With the Tlingit the name for Venus is: “It is becoming daylight” (de Laguna 1947:797). To the Tsimsian, Venus was: “The evening star is the Sun’s daughter” (Boas 1909:454-5), and “The evening star is the white Bear in the ‘Asdiwal’ sky tale” (Boas 1912:109).

Stars in General

The Carrier had a name “sem” which referred to all stars and the word “ya” which referred to the “sky, firmament, ya” (Morice 1932:25).

The Secwepemc said “stars are “holes in the sky roof which let wind in.” To Interior Salish speckers, stars are “transformed myth people” (Teit 1930:178). To the Thompson: “The stars are generally considered as transformed people”. In one legend they are described as roots growing in the upper world (Teit, 1900:341).

On the southern coast: Salish family speakers: “bright stars are old men since their eyes shine with soreness”. (Adamson 1934:356). To the Makah: “The northern lights and creatures of the sky. Stars are the spirits of people and animals that have ever lived on the earth (Clark 1953:160-161).

Stars on the northern coast

To the Tsimshian the stars are: “the tribe of the Sun Chief” (Boas 1909:454), or “people wearing silvery cloaks and living in large houses” (Barbeau 1964:171). The Haida stories of stars tell how: “Raven chews them from pieces of the moon and says to them: “Future people are going to see you there in fragments forever” (Swanton 1905:118; 1908:311). In a Haida tradition: “a great crowd of star people chase some earth people and become coloured when they pick up the paint that is dropped.” (Swanton 1908:451).

Shooting Stars

Like the story above by Henry Hunt, the interaction between the stars and earth people is seen in the information provided from Kyuquat consultant Sarah Olabar in describing falling stars in relation to Orion (“qaqats ts ist – 3 men in canoe”). “He saw one in bow “shooting” – a long streamer (falling star from star in ’bow’), Li etcit qaqats ts ist (Li etcit – shooting) – this is good luck for hunting, especially. (Ordinary falling stars mean nothing except show direction of wind). This always comes toward you – you take your blanket off & let it land on it. (You don’t see anything, but take blanket & keep in box – rub on our, spear or gun – what you shoot is killed in tracks (Drucker Field Notes 1933).

The polar star: “sem-lis.al, star that does not move”, is distinguished from shooting stars. The latter is called: “sem-thelsek, star that used to go off” (Morice 1932:76).

On the southern coast: “Falling stars, meteors, klo’-hi-etl, o-hwet’-lil. They indicate the death of some chief. If the meteor leaves a train, it is a female.” (Gibbs 1877). The Makah see comets and meteors as: “spirits of departed chiefs” (Clark 1953:160-161; Rooth 1962).

To the Tlingit. “Shooting stars are the embers of the ghost’s fires” (Swanton 1904:452). To the Kwakuitl: ”Shooting stars show the direction of the morning wind”. (Boas 1932:219).

The Sun

Applying generally to all Indigenous peoples in B.C., Boas comments: “The sun plays an important part in the beliefs of these tribes. It has been stated that he carries away souls. He is also believed to send dreams and to give the fasting youths revelations. After continued fasting in the solitude of the mountains, the sun revealed to him the supernatural power which was to be his helper …The sun told warriors before the battle if they would be wounded. After having received such a warning they demanded to be buried, with their legs stretched out, as it was believed that the sun might restore them to life.” (Boas 1894:462-3).

Boas indicated a characteristic of the: “southern group are sun-worship”. … “The Kwakiutl have a great number of legends referring to the raven. One of these, …refers to this legend originated among the Tsimshian and was later borrowed by the Kwakiutl. Evidently this legend is an attempt to reconcile the ideas of the Tsimshian and other southern tribes, who worship the sun, with those of the Tlingit, who consider the raven the deity”. (Boas 1888:56-57).

In traditional Lekwungen society there existed the concept of a supernatural entity referred to as the ruler of the animals or certain species of animals. James Fraser described the Sun as the “father of all the animals” and that the word for Sun and the headman of a village were the same. Supernatural experiences as told in stories, often concentrated on animal personages or Transformer beings. It was the Transformer Hayls who came from the north with his friends Raven and Mink to teach people how to live, to teach them language and how to make spears and nets.

The story of the Sun mask is told by Emma Hunt. Emma worked in the Education Division in the, then, Provincial Museum. Emma always said it was important to tell Indigenous stories to the world, to gain a better understanding of her culture:

“Long ago, a boy was teased because he had no father. His mother told him, “Do not be ashamed, you father is no less than the Sun himself.” Determined to meet his father, the lad shot an arrow into the sky. Many arrows followed until he had built a ladder into the heavens. The boy ascended. His father was pleased to see him. “I am old and weak. Tomorrow, you will replace me and journey across the sky.” So, the boy went out, wearing an elaborate costume and carrying the Sun. But he soon became bored because he had to walk slowly. Against strict orders, he began to chase clouds across the sky. Far below, the seas and lakes began to boil and mountains erupted in volcanoes. “Stop him!,” cried his father. The boy was cast from the heavens into the sea where he was rescued by his mother. Since that time, the boy and his descendants have had the right to use the sun mask”.

In the “sky land” a Saanich consultant said: “The most powerful human-like beings in that land were the sun, which was female, and the moon, which was male (Jenness 1934-36). On the Lower Fraser River a: “Woman prays to Sun to take away her loneliness” (Bouchard and Kennedy 2002:108-109). The Carrier call the “sun (and all heavenly bodies other than stars), sa” (Morice 1932:25).

In a story told to Boas at Lytton. A woman married the sun and had a son before returning home. In the story of The Boy and the Sun, the Sun gives the boy a bow to become a successful hunter (Bouchard and Kennedy 2002:83,86). In a similar story the Sun was a great chief who possessed great power and wealth, He lived in Lytton. His daughter married a man from the East who became powerful in magic and was distinguished for bravery. She had two children, but after her husband left her, she headed back home. Her father was displeased with her for not visiting and vowed that: “She shall never find me, nor enter my house”. When the daughter was near home, he turned her into the Sun as it is now. “This is the reason that the sun travels each day from east to west, in search of her father” (Teit 1898a:52-53).

The Secwepmc told how: “The shadow which ascends the mountains as the sun …is said to be a man called Sexkwa’lpen. This was discovered by a lad who had many times at evening climbed the mountains in an endeavour to pass the shadow and reach the receding sunlight. One day he was successful, and was surprised to overtake an old man climbing with the aid of a staff, he said to him, “Ah! You have long wanted to find me. Well, now you see me. I am Sexkwa’lpen, whom you have sought to overtake so often. Tell no one that you saw me”. For many years the lad kept silence, but at last thought he might divulge what he had seen. After he had told the story he expired”, “All the stars have practically the same names as among the Thompson people. Those without names are believed to be members of a war-party of earthly people who were slaughtered by the sky people and transformed into stars” (Teit 1909:597).

Among the Bella Coola, the Sun: “travels on a bridge as wide as the solstices, must be forced to turn back when he gets to the sides” and “The Sun’s rays are his eye lashes” (Boas 1898:32, 36).

The Kwakiutl explained how: “a woman conceives from the Sun’s rays” (Boas 1909:640) and the Sun’s: “halo is his cape, the sun dogs are his abalone earrings” (Boas 1905:382), and: “his daybreak mask is called ‘Abalone-from-One-End-of-the-World-to = the = Other’ (Boas 1905:397).The Kwakiutl note that: “stones turn over at the time of winter solstice” (Barbeau 1915:250).

The Haida also note: “The Sun’s rays are his eyelashes” (Boas 1894:15), the Sun “is made from a piece of the Moon” (Swanton 1905:118), and: “the Sun tramples the stars and the night” (Swan 1870:59).

To the Tsimshian the Sun: “rests in Mid-sky at summer solstice” (Boas 1909:114); “the Sun Chief tells someone all the constellations” (Boas 1909:817): “The stars are the sparks of his fireplace while he sleeps” (Boas 1909:115); “when he paints his face with red ocher there will be good weather” (Boas 1909:727); and “he wears a mask of burning pitchwood” (Boas 1909:113).

The Tlingit told how: “solar halo is a hoop which cuts people” (Swanton 1909:24). The Bella Coola said the Sun’s “daughters are mountain goats” stars (Boas 1998:803). To the Salish the halo is “Sun makes a house” (Teit 1930:178) and: “He is cross-eyed because he sees everywhere” (Adamson 1934:272). To the Dene: “the halo means the Sun is afraid” (McKenzie Delta Research Project vol 2:91).

The Moon

The Nalaka’pamux of the Interior saw “the Moon’s house is so overcrowded with star-people that a woman and a frog sit on her face, making her less bright” (Teit 1900:341).

The Carrier Dene, with regard to the word month, “when speaking absolutely, have for an equivalent sa-nen, sun (or moon) duration, which is, however, constantly shortened to -za when in compounds connoting intimate relation. Original sa means as much moon as sun; but when a distinction becomes necessary, they say ‘the sun of the night’ for the former.” (Morice 1932:58).

Among the Shuswap: “Once the moon was a man. He had two wives” (Bouchard and Kennedy 2002:80), and: “The face of the Moon is said to represent the figure of a man with a basket on his back, and the name of this man is Wha’-la” (Dawson 1892:89); and: “Man in Moon’s face caries a basket” (Dawson 1892:39), and “the Moon’s wife jumps onto his eyes, we see her and a basket” (Boas 1895:13). The Salish see the halo as: “Moon makes a house” (Teit 1930:178).

Moon traditions on the Southern Coast

In Sahaptin Folk Tales of the Sun and the moon: “The Sun had two wives, Frog and another woman. … Coyote decided that Sun should become the night sun (Moon), and that the Moon, and the form is seen over his eye.” (Boas 1917).

Olson notes the Quinault of Washington believed that: “A waxing Moon at the winter solstice means a lean year will follow; a waning one is a sign of a plentiful years”- “The Moon-tide relationship was clearly recognized, and followed by the whalers” (Olson 1936:176-7). Southern Coast Salish say “the Moon has stronger eyes than the Sun, and would burn everyone if it went around in the daytime” (Adamson 1934:272).

Central and Northern Coast

The Kwakiutl indicate that the Moon: “she is consulted to see whether it is herring season yet” (Boas 1905:376). The Nuhalk (Bella Coola) saw: “a woman in the moon’s face has a pail and berries” and was a “daughter of heaven chief” (Boas 1909:864; 800).

The Haida believed the Moon “is chewed to pieces to make the Sun and stars” (Swanton1905:117). The Tsimshian saw the moon as “the jealous brother of the Sun, and is called “Walking about early” (Boas 1909:114).

The Tlingit say the moon “is a great chief who loves to have his slaves paddle him from village to village so he can visit” (de Laguna 1947:848), and “the Lunar halo is a sharp ring which tells the weather” (Swanton 1909:98).

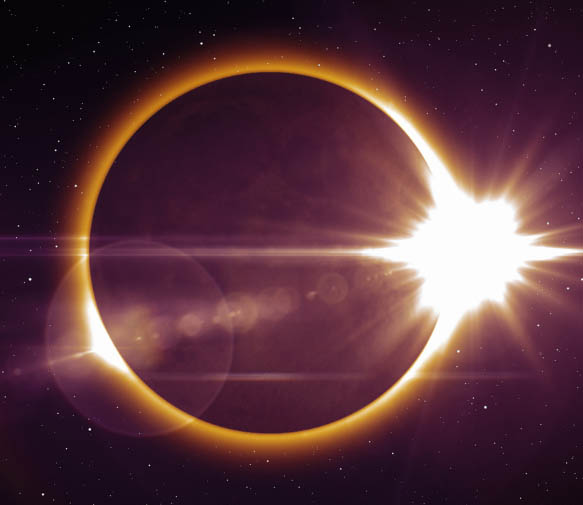

Eclipse of the Sun and Moon

Jimmy Fraser of the Songhees said: “Codfish is the oldest brother” – “Codfish bites the sun (Eclipse)” (Duff 1952). Carmichael recorded stories from the Tseshaht and Opetchesaht of the west coast of Vancouver Island:

“The sun and moon emerge from out the house of Nas-nas-shup. The giant codfish guarding the entrance to the house, attempts to catch them passing. He often fails, but there are times when he succeeds, then there is darkness–an eclipse of the sun or moon the white men say, but that is false, it is the cod. The many stars which sparkle in the skies are Indians, who dwell above the earth. Such things and many more were told by him, and Eut-le-ten was counted as a chief more learned than any that had ever been” (Carmichael 1922).

A Nuu-chan-nulth consultant, Mary Jack (wife of Old Captain Jack).

“They had songs for lunar eclipse. Ma’it (bite) maiea’tîc hüpat. Big codfish – ‘tuckai i am’ (eating). Sometimes go outside – put boards down, drum and sing – to drive Cod away – keep ch. [children] outside, wish pull in fish etc. so will be good fisherman etc. … ‘nasîyû’ma îL’ – solar eclipse – the cod again they sing and drum, yell, to scare away” (Drucker 1933).

The late George Louie of Ahousaht, told me how the names for eclipse included the words for bite and moon and bite and sun. Another version was translated as “Swallowed the sun”. One story talked of the Cod fish swallowing the sun or moon. George said in the stories he interpreted: “There was the belief that the cod fish swallowed the moon or the sun”, and “There is bound to be a storm after eclipse of the moon or the sun”.

To the Tlingit: “An eclipse happens when the Moon is visiting her husband, the Sun”. (Speak 1945:390). Among the Salish: “a Lunar eclipse occurs when the Moon covers her face or eyes in embarrassment” (Boas 1932:178). For the Kwakiutl: “eclipses are caused by a heaven mouth devouring the body; prayers are made to have it vomited out again” (Boas 1950:179). A Quinault story mentions: “Fisher sometimes grabs the sun and moon and eats a piece of them” (Clark 1953:160).

“A very old Saanich (Tsartlip) Indian affirmed that now and then the sun caught an extra, large cod, and only by a desperate struggle succeeded in killing it. During the struggle the sun was eclipsed through the cod passing in front of it, whereupon he and his family summoned to its aid the swiftest of all birds, the hummingbird, chanting ‘Go up, hummingbird; go up, hummingbird’. What caused the eclipse of the moon he did not know, or did he concern himself greatly with the event” (Jenness 1934-36).

The Milky Way

The dominant themes of the Milky Way in British Columbia, is that of a river, trail, tracks or road of the dead, as well as a division point of the sky. In eastern Siberia it is a pebbly, clay or muddy river.

General comments on the Northwest Coast indicate: “Teluwa’met, the Milky Way, is the place where the two parts of the sky meet. It is the road of the dead. (Boas 1894:463). “The river that flowed through sky-land was the Milky Way.” (Jenness 1934-36). Lekwungen, Jimmy Fraser noted: “Milky Way – mark where sun goes. Called sta’lu ‘river’. That’s where fish come from. (same word all Coast Salish languages)” (Duff, 1952).

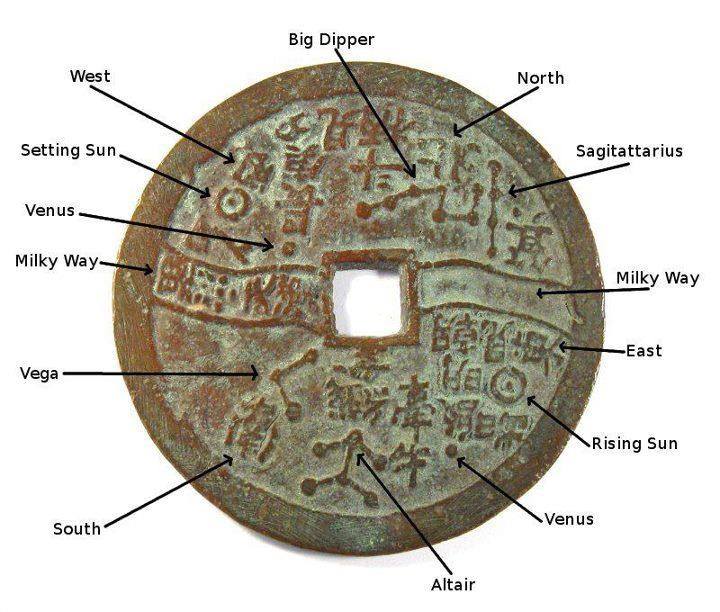

Many Asian cultures also saw the Milky Way as dividing two parts of the sky. Figure 16, shows a example on a Chinese talisman with the Milky Way as a dividing point. It divides the north and west from the south and east sky and divides morning and evening as seen by the examples of the morning and evening Venus in relation to the rising and setting sun.

In the Interior of the Province, among the Secwepemc: “The milky way is named chiw-i-wi-ow’-is, the road or path of the dead.” (Dawson 1892:89). To the Thompson it is a “the trail of Stars” or “what has been emptied on the trail of the star”’. that have “been emptied on the trail”, “the Grey trail” and “Tracks of the dead” (Teit 1900:342). The Milky Way is called: “Dusty Road” (Teit 1930:178).

The stars without names are “believed to be members of a war-party of earthly people who were slaughtered by the sky people and transformed into stars. The Milky way is called “Trail of the dead” and is said to have a dusty trail used by dead people, which was transformed as we see it.” (Teit 1909:597). To the Ktunaxa, it is “Dog’s Trail”. (Dawson, 1892:575).

Among the Kwakiutl of the Kwakwaka’wakwa people, the Milky Way is: “As the sky trail in the Orpheus Myth of the Northwest Coast” (Barbeau 1964:271); “as the cannibal pole of Cannibal-at-the-North-End-of-the-World” The Polaris figure who is central to the Winter Ceremonials. (Boas 1894:446); a “man asks to be transformed into an everlasting and ever-seen river.” (Boas 1906:229); and “Seam of Heaven”, a head ring worn during the winter Ceremonials. (Boas 1905:415).

Kwakiutl, George Hunt wrote: “Notes on a Head Band” in regard to artifact RBCM1945 in the Royal B.C. Museum collection: “This is the ‘Milky Way’. Two side pieces. Double piece on front end shows the shadow mask of No. 1916. It is the sign that he has the mask also. The Spirit met the man who was hunting for mountain goat and the spirit of the Cannibal said ‘Here is my big dog, I will give you it to hunt with’. So he took this dog wrapped it up and put it on behind the head. So this mask carries the Milky Way and the double mask of the dogs. In front are the dogs. ‘Then you see, take the dogs down put them on the ground and they will grow up full size. Then they will go and get the goats for you and every time you finish with it put the dogs back, pick them up from the ground’. This is what the Spirit told the mountain goat hunter. That is all.” (George Hunt, Sept. 1922:4).

“Milky Way. In the hawinalal dance – true war dance – Winalagilis is represented as Milky Way to which the dancer is pulled up. Power of Winalagilis (sisiul) keeps hold of him. Beam represents Milky Way – tied to hawinalal dancer who is pulled up into the air. Wearing sisiul girdle, stabs himself with a knife representing the sisiul. Sisiul connection with moon. Head ring represents the moon. House of Bahbakualanuxsiwae contains cannibal pole representing the Milky Way, but also rainbow, has a cosmic significance. “Centre of the earth” – “Post of our world”.To the Tlingit the Milky Way is a: “Wide trail or beach” (Swanton 1909:251) or “as a forked path of the dead travelled by a shaman” (Boas 1889:843); or “as tracks left after a chase through the sky” (Swanton 1909:102, 297).

The Tlingit consider: “All those having died a violent death go to the sky where Tah’t reigns” – “The souls dwelling with Tah’t cause the northern lights. When it appears blood-red, they prepare for war. The milky way is a long tree trunk lying there, across which the fighting spirits (the rays of the northern lights jump back and forth. Tahi’t is master over men’s destinies. He decides who shall fall in battle. When a child is born, he decides whether it is going to be a boy or girl and whether the mother is going to die in childbirth.” (Bouchard and Kennedy 2002:624-627).

The Rainbow and Aurora Borealis

In the Interior: “The Rainbow is said to have once been a man, a friend of Thunderbird, who was in the habit of frequently painting his face with bright colours (Teit, 1900:342). The Makah saw the rainbow as: “An evil being associated in some way with the thunderbird” (Clark 1953:160-161). “The aurora borealis is named ‘s-s-u-am’, which appears to mean ‘cold wind’, but this is uncertain” (Dawson 1892:89).

The monthly Moon Cycle. The Calendars.

Linguist, Edward Sapir noted in regard to the moon cycle:

“Not all families count alike. One family is sometimes one month ahead, or one month behind another. Sometimes they quarrel about what month it is. The names being well known, but the exact order in which occur and the exact time of the beginning of each month being somewhat open to dispute” (Sapir 1909).

Moons sometimes had individual names, numbered in sequence for summer and winter portions of the year. They might be called: ”big brother”, “elder”, “younger sibling” or “first moon”, but often were named in relation to plant or animal resources that appeared at the time.

Among Indigenous cultures, as in others, time is divided with the sun’s shifting rising on the horizon, A year usually began in summer or at the time of the winter ceremonies. The start of seasons in the northern hemisphere is with the March equinox at the beginning of Spring, the June solstice of summer, the fall equinox of autumn and the winter equinox of December.

A solstice is the time when the sun reaches its most northernly and southernly position in relation to the celestial equator on the celestial sphere. Two solstices occur annual around June 20-22 and December 20-22.

These solstice features of the sky are interwoven with the availability of food resources of game, or the condition of game (i.e. Game are moulting), the ripening of plants and climatic conditions (Leaves falling). However, the names of months may refer to an activity that is not reflected the name but may be linked to it. For example, the Haida word: “SEan gias (“Killer whale month”) – So named because cedar-bark is then stripped from the trees and the noise made in doing it is likened to that of blowing killer whales” (Swanton 1903).

We are all familiar with the different numbers in the days of the months and the intercalary day of February 29, that is inserted into our modern calendar every four years to ensure that the calendar stays aligned with the seasons. Indigenous people also had intercalary days which they coordinated with the moons that may be extended to fit the nature of food resources or ceremonies. There were two different times this was done in Haida culture. Among the Masset Haida: ”Q!e’daq!edas (“Between month”) – This was so named because it is the intercalary month between the summer and spring”. Among the Skedegate, “Ge’tca q!a’-idas (“Between month”) – The name of this month is explained by that of the intercalary month in the Mass series” (Swanton, 1903).

Many accounts of Indigenous calendars have been published. One of the best of the early accounts was collected from the Mowachaht at Nootka Sound in 1792, by Don Francisco Mosino. See Appendix 1 for his full account. Also see Appendix 2 for examples of the naming of modern months.

Lunar months were recognized and divided into 11 to 13 named months. Days are not usually given specific names. As Morice points out: “As to the Carrier, names for the days of the week, they are partly French words ending in -dzin, the exact equivalent of French -di and of English -day, roughly conforming themselves in their computations to the Latin feriea [Festival] of the modern ecclesiastical week.” (Morice 1932:58).

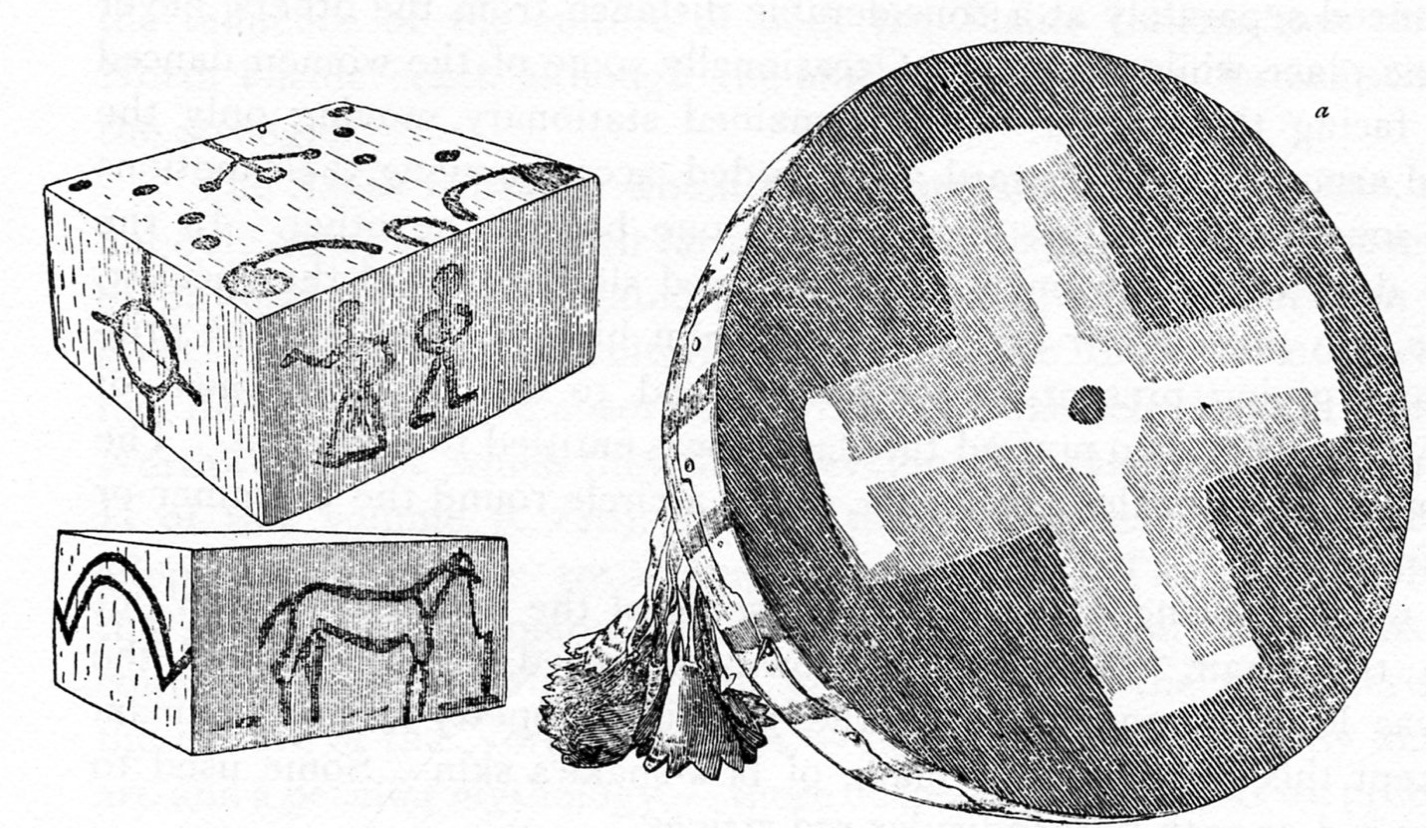

Artifacts and Astronomy

Phenomena of the sky are mainly presented in stories and word lists, but they are also incorporated into artifacts that include everything from small drinking tubes and masks to crests on large memorial poles. An example of the latter is found among the Gitksan on the upper Skeena River (Fig. 18). The memorial pole of Gurhsan at Gitsegyukla, is called Pole-of-the-Moon. In the moon crest is “Skawah, the ancestor of the clan with earthquake (Tsa-urh) charm in her hand”.

The long narrative of the Nation describes how the maidan Sawah, was rescued by “Rays-0f-the-Sun, a sky spirit”. She experienced, “the birth of several children to her in the Sky, their education, their training, and finally their return to earth”. They developed heraldic crests which were “symbolic of their noble origin, in particular, the moon, the stars, the rainbow, and the bird of the sky” (Barbeau 1929:89).

Figure 18, shows a closeup of the crest from plate XIV, figure 2, of Barbeau. The earthquake charm of Skawah was a bucket-like vessel given by Ray-of-the-Sun to has “semi-divine children”. When tilted it caused earthquakes to crush their enemies.

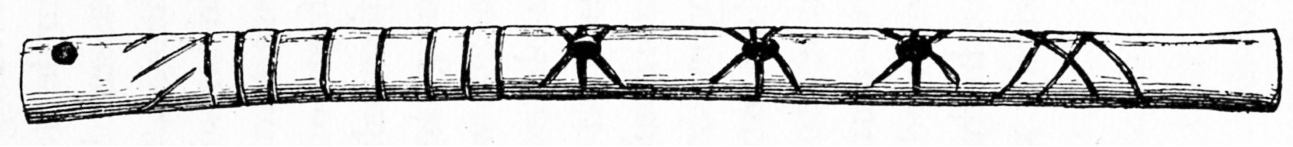

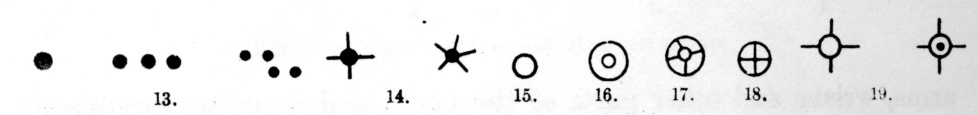

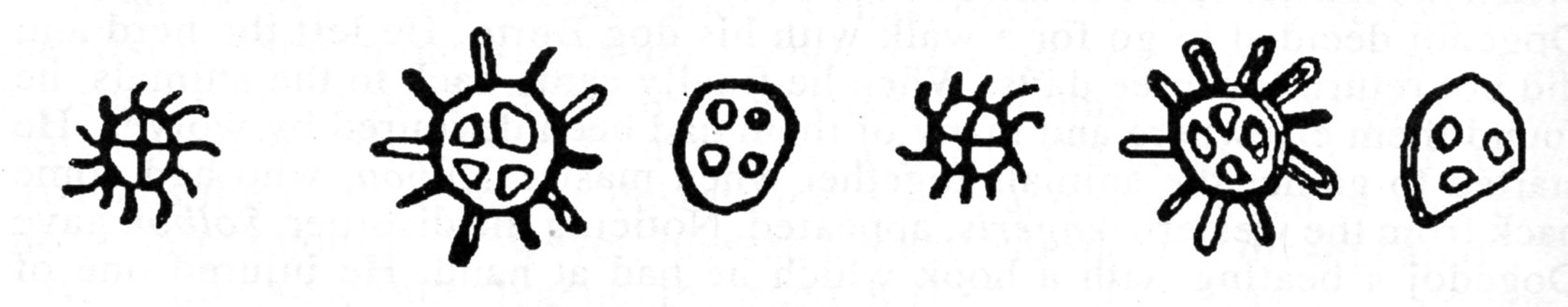

Symbols identified as crossing trails are common but could be misinterpreted as stars. Teit shows the distinction between star patterns and cross-trail patterns in an example of symbols on a drinking tube, used in girls’ puberty ceremonies (Fig.19), The crosses on the holes represent stars and the those at the ends represent crossing of trails. He notes: “Designs representing the guardian spirits and supernatural dreams of the owner are very frequent. These were believed to be the means of endowing the implements with supernatural powers”. He notes: “Designs representing the guardian spirits and supernatural dreams of the owner are very frequent. These were believed to be the means of endowing the implements with supernatural powers.” (Teit 1900:379).

Rock Art and Cosmic Relationships

Examining the evidence of cosmic relationships expressed in Pictographs and petroglyphs is difficult without sound information acquired from knowledgeable Indigenous people who were part of the traditional experience of producing them or obtained information directly from older individuals that were.

Anthropologists working in the late 19th century often expressed how there were only a few older individuals left that had any knowledge of the subject matter. Petroglyphs in particular mostly seem to be older than pictographs and have few stories connected to them. However, because they have been around longer, they may have acquired stories that may or may not be linked to their original creation stories. Like all verbal stories, they change over time.

Harlin Smith sent a note to Charles Newcombe of the Provincial Museum after visiting the petroglyphs near Bella Coola. He noted: “They say that a family had ‘power’ under a large rock nearby, They cut out the pictures in time to songs which were sung in connection with this ‘power’. Not even the oldest Indians know what any of the pictures represent. This family had a ceremonial house immediately south of the largest exposure, and a hunting trail up the valley pasted passed over part of the petroglyphs and through the house” (Smith 1923).

Examining the locations of Rock Art may provide patterns that help provide a better understanding of why they are located where they are and what is represented by, at least, some of the symbolism. We can match symbols with those painted on clothing and other objects of material culture that have trustworthy descriptions, such as items related to gambling, winter dances, or shaman’s offerings.

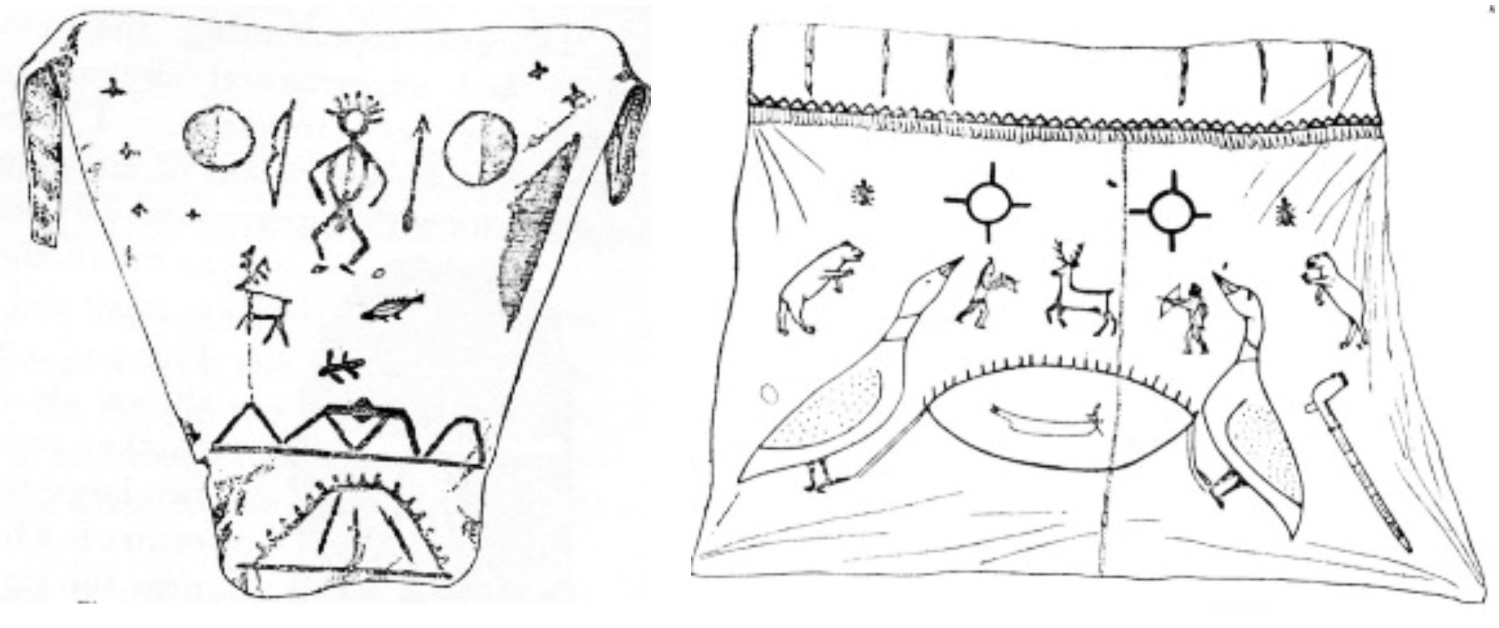

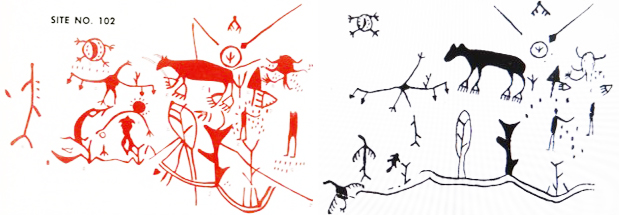

Pictographs and the Cosmos

The imagery of pictographic symbols is not a random factor but a culturally controlled and cultivated phenomena. Among the Interior Salish spirit identity and the power, which a spirit was believed to give, were associated with visible fabricated objects. Some of these in a three-dimensional object form and others in a two dimensional, symbols on object, form. The main social purpose of these objects is to provide a visual social confirmation that the maker or possessor has been empowered through a vision experience and is therefore deserving of a particular social role (Keddie 1982).

Since guardian spirits could be represented by almost any animal, insect, plant, inanimate objects such as rocks or lakes, heavenly bodies or natural phenomena such as thunder or fire, there may seem to be almost limitless possibilities for pictographic representation. However cultural selection plays a role in giving preference to specific sets of spirit representations and it can be expected that these are visible on a regional basis.

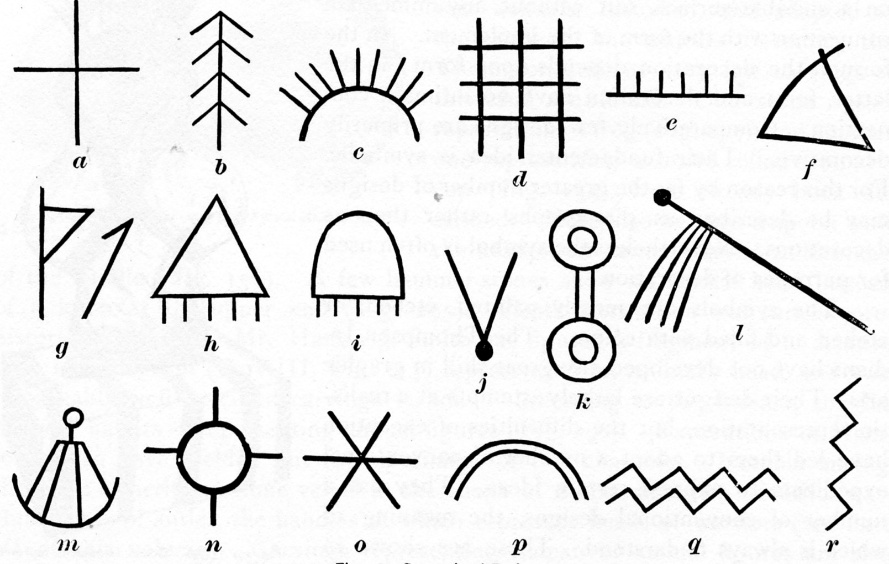

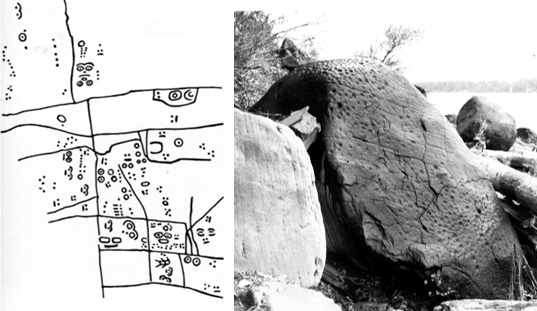

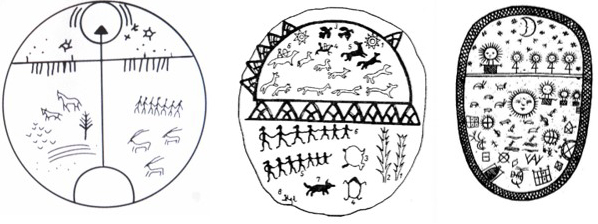

There are designs that Teit indicates are conventional: “They use a number of conventional designs, the meaning of which is always understood”. He shows these, where n, o and p represent sky features (Figure 20).

Pictographs of the Sun and Venus are most likely spirit powers acquired during vision quests. Adolescents prayed mainly to the Day Dawn, when Venus arose, and many warriors prayed principally to the sun. Every morning one of the oldest members of each household went out of the house at the break of day and prayed to the Day Dawn (Teit 1900:344). Everyone made prayers or offerings to named deities or powers inhabiting specific localities (Teit 1930:291)

Numerous animals and plants could become guardian spirits but their powers varied. The favourite guardian spirits of shamans included: “Heavenly bodies: sun, moon (rather rare), stars, Milky Way, Pleiades, Morning star” as well as natural phenomena such as rainbows and mountain tops (Teit 1900:354).

Pictographic images may be individual or part of group scenarios. Many of these, include symbols of the Sun, Moon, stars and rainbow, that connect them to the sky. However, the associated animal imagery is often suggestive of hunting and fishing activities of an earthly nature rather than stories connected to the sky.

James Teit writes in regard to his fig. 252 pictographs: “most of these pictures were representations of objects seen in their dreams, and the painting of them was supposed to hasten the attainment of a person manitou or other desires.” (Teit 1909:590). “Most men had several guardian spirits, but one was much more powerful than the others”. (1909:606).