2018.

By Grant Keddie

Introduction

Wooden and antler wedges are a common tool found in the Northwest Coast cultural area of North America. The purpose of this article is to drive a wedge into our current thinking about wedges and to stimulate further research by making some observations based on Royal B.C. Museum archaeological and ethnological artifacts. I combine this view of collections with my own background experience in working with wedges.

Wedges are commonly known to have been used for splitting fire wood, for the manufacture of posts and planks used in house construction, household items such as boxes and bowls, and for the whole process of canoe making from cutting down trees to splitting the tree trunks and carving out the canoes.

When archaeologists find antler wedges in old shellmidden sites their presence is usually interpreted as evidence of wood working activities. Wedge shaped antler artifacts, however, do have a number of other uses, the most significant is their use in the repairing of canoes and in hide working, as well as the general use of their proximal end as a hammer. This article is intended to bring about the awareness of the need for more experimentation, fine scaled observation and analysis of what we normally call antler wedges.

Canoe Repair Wedges

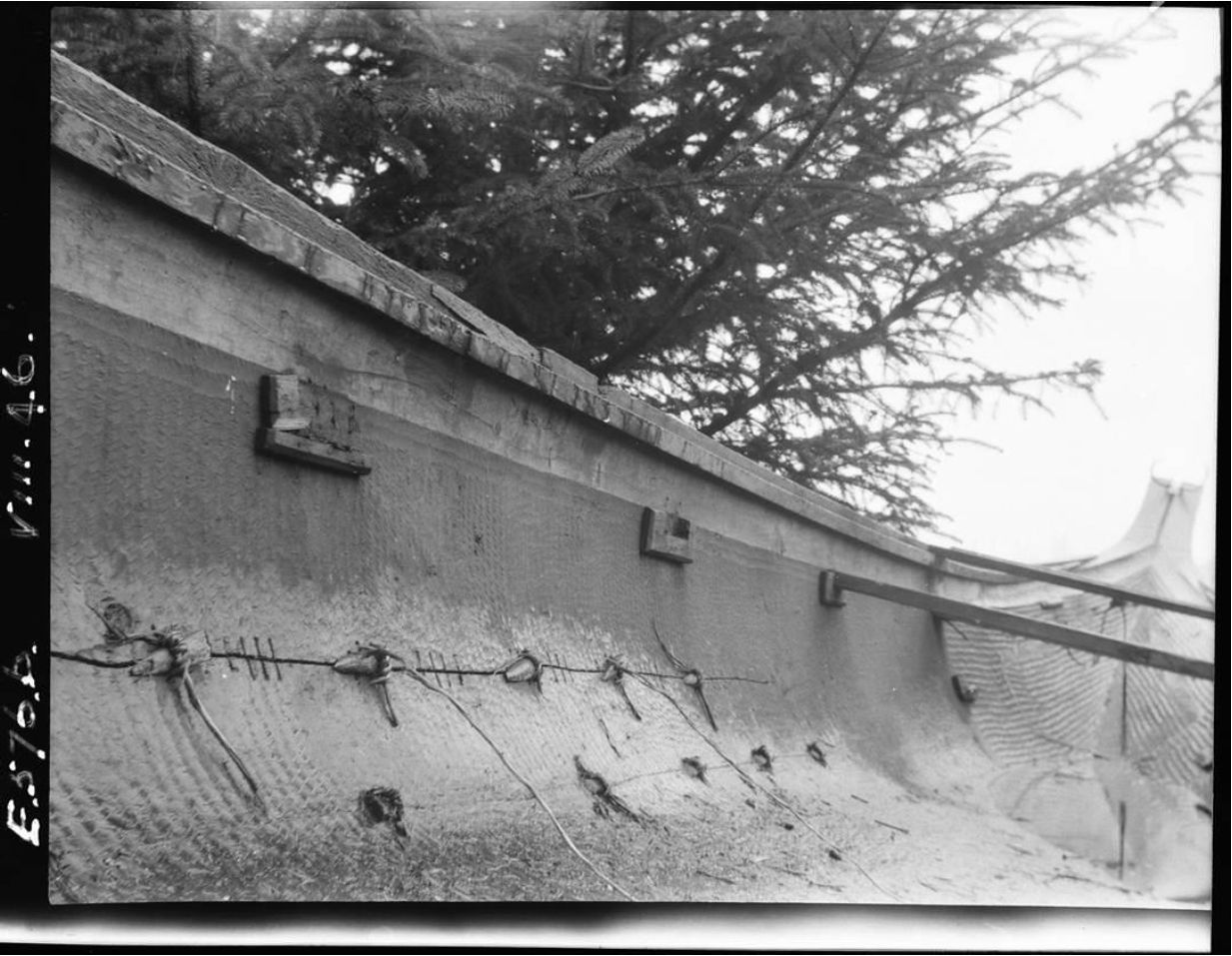

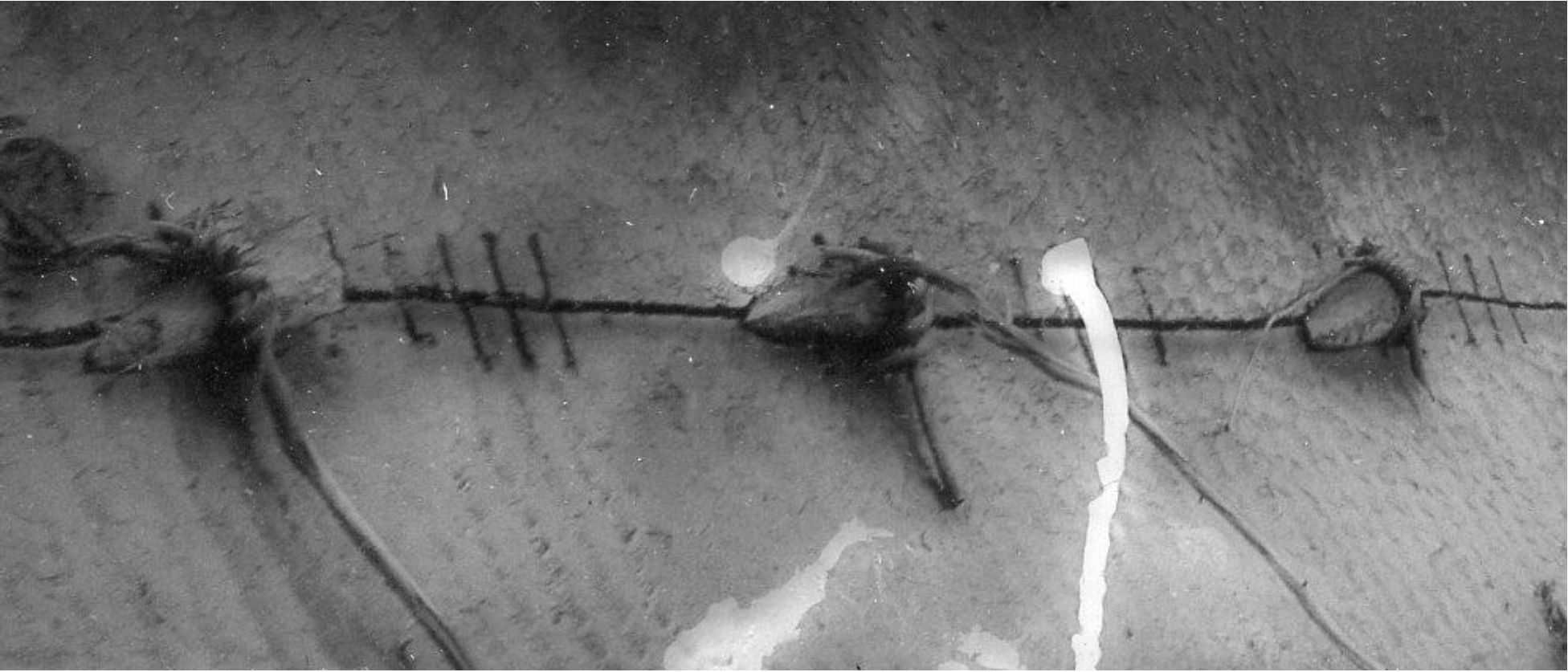

This inside of a canoe (Figure 1&2) was photographed by Charles Newcombe in 1913, at Alert Bay on northern Vancouver Island. Although no commentary was preserved with it, Newcombe obviously took the photograph to show the ten antler wedges being used to repair a major split in the side of the canoe. There are likely, at least several more wedges that cannot be seen in the image.

If this canoe was pulled up from the beach long ago and left to rot on land, a concentration of antler wedges would likely became buried in an archaeological shellmidden site. The presence of all these wedges in close proximity to each other would likely be mistakenly interpreted by archaeologists as the location of extensive woodworking activity.

The use of wooden wedges for canoe repair has been minimally known about, but photograph RBCM PN629 is important in clearly showing small antler wedges in canoe repair as late as the early 20th century.

Why Use Antler Wedges for Canoe Repair?

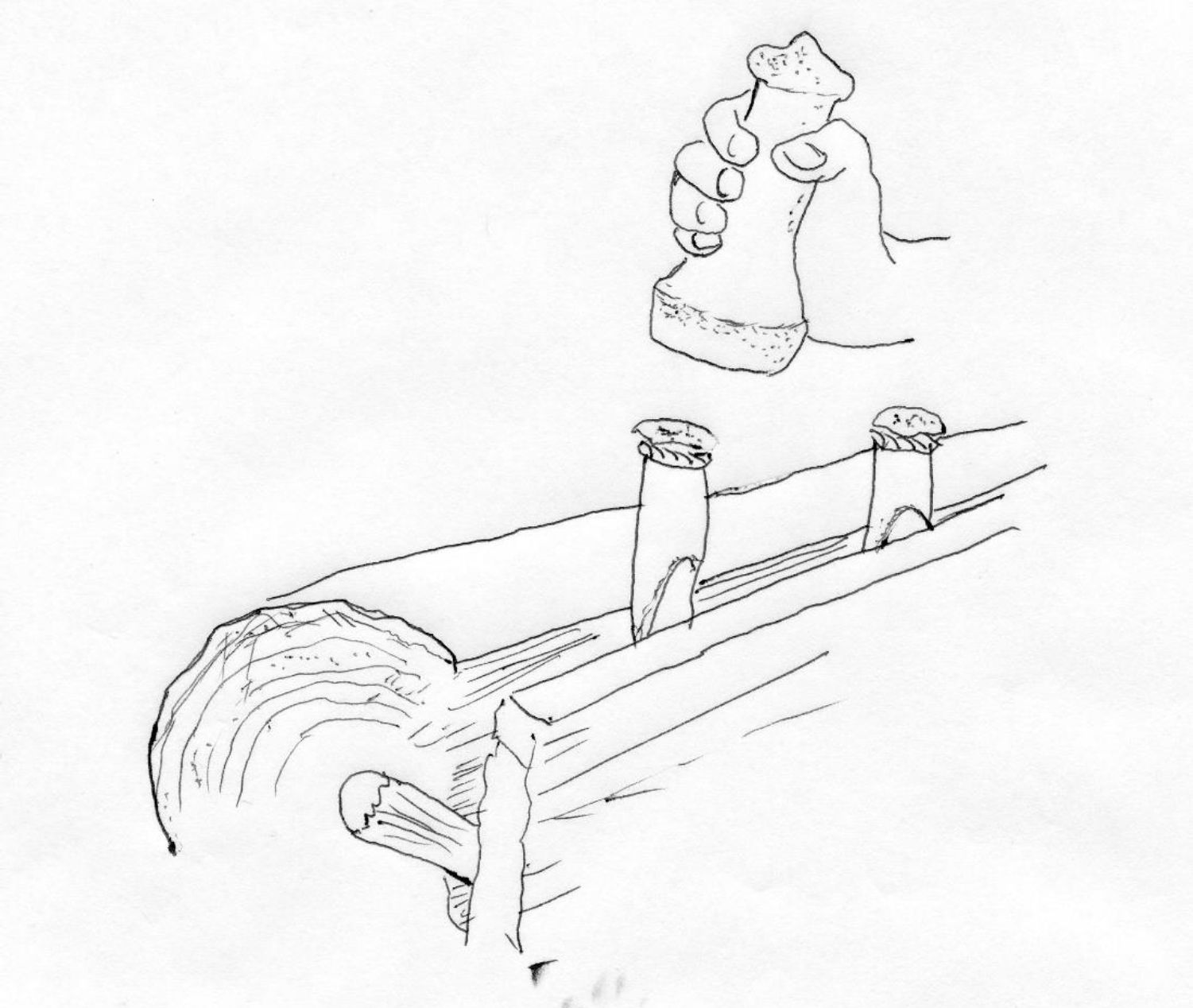

When the canoe sides begin to split, holes are drilled into each side of the crack and twisted bark rope is strung across the crack. In order to firmly tighten or pull the boards together a small antler wedge is pounded between the ropes and the side of the canoe to pull the boards tighter together than can be done by simply pulling and tying the rope by hand.

A significant statement was provided by First Nations consultants of Waterman about wedges used in Puget Sound (Waterman 1973). He noted that: “They were made of yew, or of hemlock knots, or of elk antler, the last named being the best”. Waterman worked with Indigenousadvisors in the 1919-1921 period – their experiences would go back to the 1850s. Although he does not mention why antler is best, I would surmise that one of the benefits of antler is the fact that it does not shrink and expand as much as wood – making it better for long term canoe repair jobs. From my own experience in using antler wedges for splitting wood, antler can keep a tougher distal end than wood and not split as easily as some types of medium to hard woods.

The Reworking of Antler wedges

Both antler and wooden wedges vary enormously in size. It appears that most of the antler wedge-like artifacts we find in Archaeological sites are the broken fragments and re-purposed portions of previously larger examples (figure 3). When longer antler wedges are broken or weathered down by use, they usually break near the tip and become too small to use as wood splitting wedges. They then can be more appropriately used as canoe repair wedges (figure 4). Many short broken wedge tips show post breakage pounding or compression on their proximal end – which demonstrate that they were reused. Archaeological collections contain many broken wedge tips that also show evidence of being graved into smaller pieces to be used for making other objects such as antler projectile points (figure 5).

Observations of Wedge Use

During his travels along the lower Columbia River in 1824, George Simpson of the Hudson’s Bay Company observed: “Our Iron Works are not as yet come in to general use among them; they have no occasion for Hatchets to fell timber as their shores are covered with Driftwood which they split with wedges” (Merk 1931:103).

When reading the ethnographic literature on the use of wedges, it helps to have a bit of personal experience with the subject matter in order to judge or interpret what is being reported.

Starting when I was six years old, I often used an axe to cut down trees and split wood for the stove in our cabin at Skeleton Lake Alberta. This wood splitting experience was helpful when I later had to root out 300-year-old tree stumps. When I was 13, I was given a specific job of splitting 120 ten foot poles of hemlock and cedar to make 240 fence posts to enclose our new property in Surrey, British Columbia.

I started off with two steel wedges which I soon lost inside partially split logs. I was forced by necessity to make an increasing number of wooden wedges. I soon remembered the importance of the width and thickness of the wedge in relation to the splitting edge and how multiple wedges were needed to be used in concert with each other. A series of wedges that are flat in relation to the cutting edge could be used on cedar with near perfect grain structure, but thicker wedges on both the top and sides were usually required for controlling the split.

Anthropologist Franz Boas reports that seven sizes of wedges were being used to split boards among the Indigenous peoples on the north end of Vancouver Island (1909:253&324). See figure 7 for the distal end shapes shown by Boas. Anthropologist Phillip Drucker (1951:80) notes the practice of using eight to a dozen small wedges across the top of a split tree trunk to remove a large board. These are used to get the split started and then they are replaced with larger wedges

First Nations Canoe Wedges

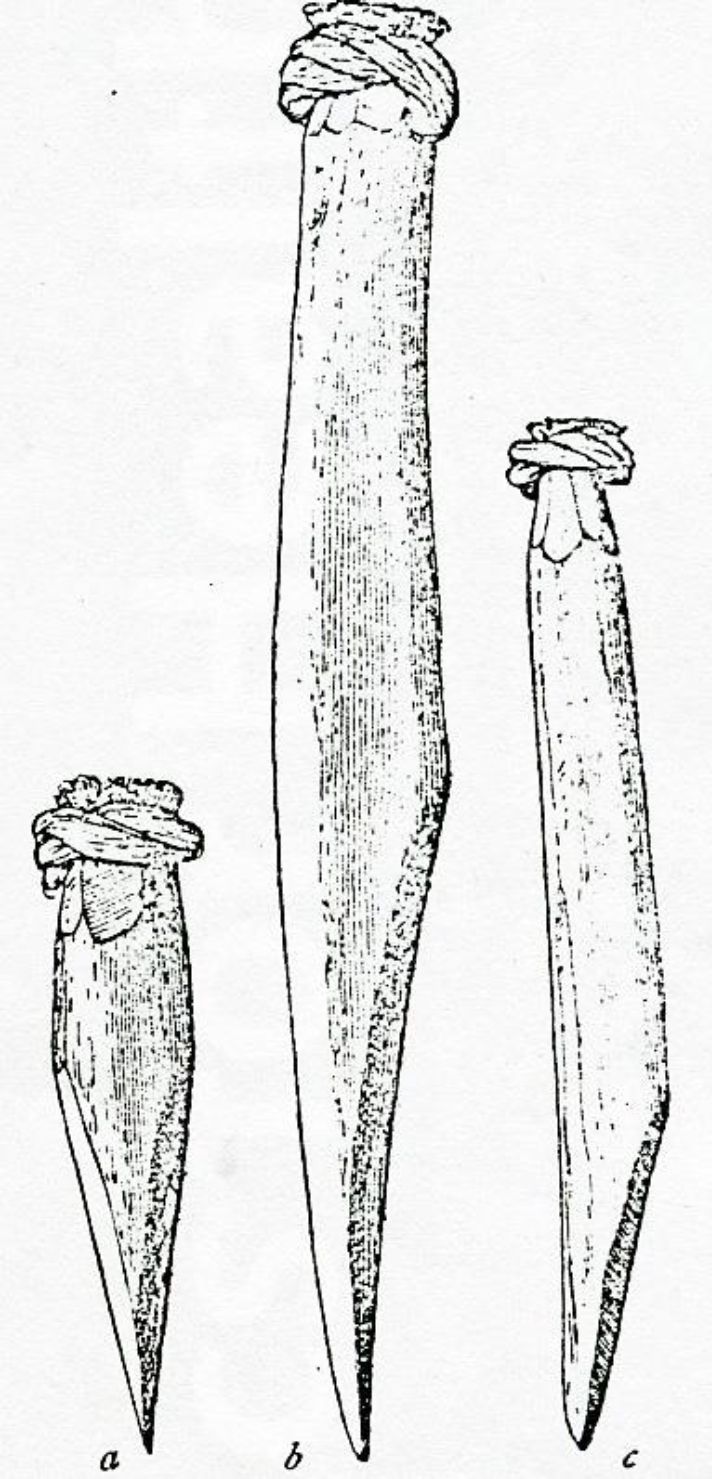

We are fortunate in having a detailed description by Boas (1909:323-324) in the making of wooden canoe wedges (figure 7). Indigenous advisors told him that one should cut four pieces of yew wood to different lengths. What is significant here, is that even the smallest wooden wedges described are much bigger than what appear to be complete antler wedges found in Archaeological sites. I have only seen (in a private collection) two elk antler wedges of an archaeological nature that are over the 30cm size mentioned below. These were found together just below the surface in a rocky bush area above the N.W. corner of Bay and Cook Streets in Victoria.

Boas gives the measurements in spans-distance from the tip of the thumb to the tip of the middle finger. I will use 9 inches or 0.2286m for the usually accepted English standard for a spam. For fingers, I will use 19mm or 3/4 inch. I will record these to the nearest cm. Given these standards, Boas’s seven canoe wedges of six different sizes (the last two being the same size)would be: (1) 76cm (2) 69cm (3) 53cm (4) 46cm (5) 30cm (6) 23cm (7) 23cm. Unfortunately, a description of how the various sizes of wedges are used in the production of a canoe is not explained. Wooden wedges generally had twisted plant fibre grommets on the end to prevent splitting (See figure 8a&8b).

Alter wedges used as an axe head

Sproat, from observations made in the 1860s, indicates that, in canoe making among the Nuu- chan-nulth of the West Coast of Vancouver Island, the tree trunk was split in half with wedges and the best half used for making a canoe. An “axe used formerly in falling the largest tree …was made of elkhorn [antler], and was shaped like a chisel. .. .This chisel-shaped axe, as well as large wooden wedges, was also used in hollowing the canoe” (Sproat 1868:86). It is uncertain here if Sproat is referring to a wedge hafted in the mid section like a modern axe head or an antler chisel-like wedge pounded with a stone hammer.

When Drucker visited the same area in the 1940s, he pointed out that none of his indigenous consultants knew of the elk antler chisels described by Sproat (Drucker 1951:78).

Antler wedge shaped hide processing tools.

The most common land mammal remains found in archaeological sites in British Columbia are those of deer, with elk and other ungulates being prevalent in some areas. The preparation and wearing of animal hides by coastal peoples is downplayed in reports in favour of the wearing of woven clothing. This, in part, is due to a lack of knowledge as to what artifacts were used in the processing of hides on the coast – in some areas this information is lacking in the ethnographic literature – especially on the southern coast.

Boas reports on the use of yew wood wedges in the processing of the hides of large animals such as elk and bear. It is likely that antler wedge-like artifacts would serve the same purpose (figure 9). After elk hides have been soaked and hung up in preparation for further work: “the woman takes a scraper, consisting of a wedge of yew-wood, and scrapes it downward on the hair side. Thus all the water is squeezed out. Then the flesh side is scraped with the back of a cockle-shell which is fastened to a long handle. When all the fat and tissue have been scraped off and all the water has been pressed out, it is scraped down once more with the shell scraper (figure 10). Next the whole hair side is rubbed thoroughly with a little oil of the silver perch, and is scraped once more with the yew-wood wedge until the oil has been pressed out again. The skin is put in the sun; after this, it is scraped once more until it is quite dry” (Boas 1909:400-401).

Examples from the RBCM Archaeology Collection

Some antler artifacts described as “wedges” have sharply turned angles which would make it unlikely that they were used for splitting wood. Others with slight curving distal ends (figure 11) would be suitable for the removal of wood in shaping the sides on the inside of a canoe. Some of the longer “wedges” with long tapering and flatter distal ends would function effectively as hide stretchers (figure 9).

Some shellmiddens on the south-eastern coast of B.C. contain large numbers of whole or portions of antler wedge-like artifacts. Figure 3 is an example of antler wedges from archaeological site DcRt-16 in McNeil Bay, Victoria dating between about 500 and 200 years ago.

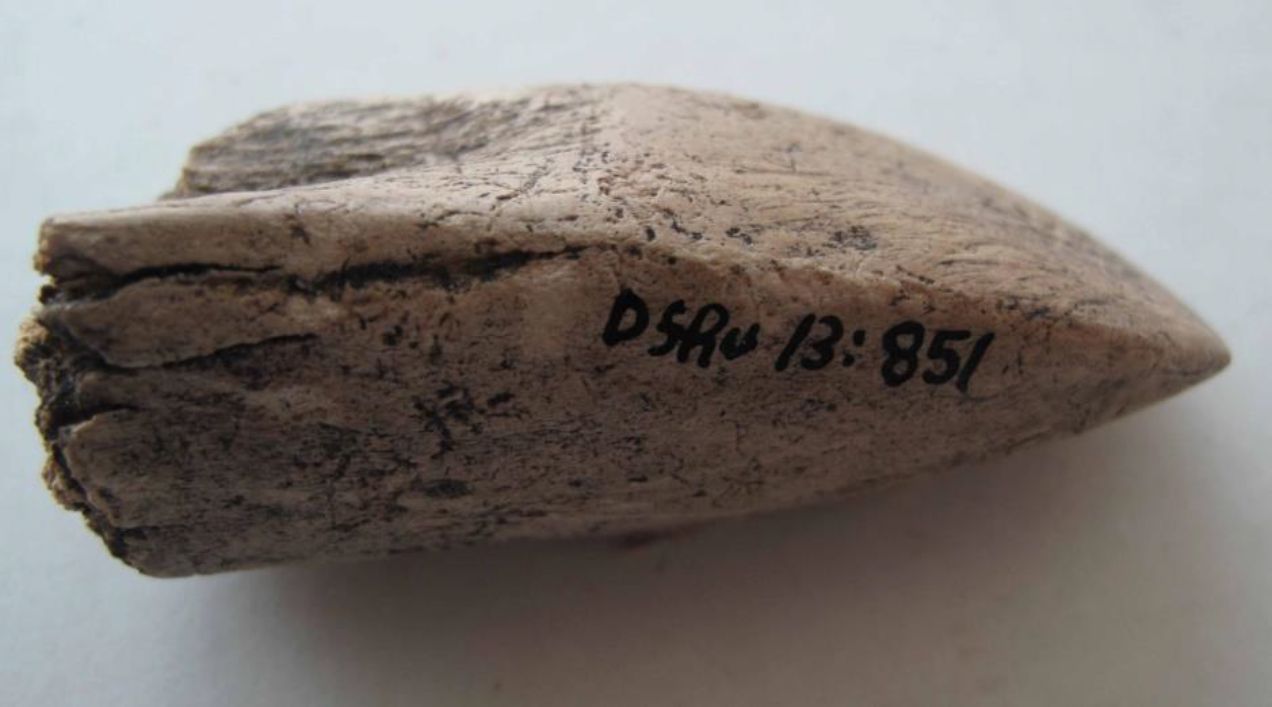

Figure 12,shows a common example of a short stubby elk antler artifact that has been broken off a large wedge and re-used – judging by the evidence of pounding on the proximal end (DcRt- Y:102; Length 152mm; width at mid-section 30mm;18mm wide at a distance of 10mm from the distal end and 37X40mm at the proximal end). This is a likely example of a wedge re-used as a canoe repair wedge. Figure 16 shows very different distal ends on two small antler wedges. The wedge with a pointed end (DcRt-15:4202) would have had a specialized purpose. Figure 17 shows three wooden wedges from water-logged sites. The two on the left are shaped from both sides to form the triangular point. Both are over 2000 years old. DcRu-74:88 has been burnt on the tip to harden it – as was known in historic times.

There is one example of a large wedge made of a whale rib bone (14250) in the ethnology collection like those found at the Ozette Village site (Figure 18). Based on the condition of this artifact, I suspect is actually from an archaeological site and has recent material tied around the neck.

Additional Uses of Antler Wedges

Boas recorded several other uses of antler wedges. The proximal or flat ends were used as hammers for breaking open Sea Urchins – often referred to as sea eggs (figure 13). Boas notes this activity among the people of northern Vancouver Island: “His wife often carries a yewwedge to break the sea eggs” with a grommet of cedar twigs at the upper end to prevent splitting (Boas, 1921:491). He also indicates that the wedge was used as a beater in fish preparation (Boas 1921:387-394), and as a hammer in the preparation of octopi tentacles to use as bait on fishing hooks. After the pieces of octopi tentacles are dried they are placed on a board and pounded flat with a short wedge. A man in: “His left hand holds the piece of devil-fish, and with his right hand he holds the flat point of the wedge; and he pounds the devil-fish with the other end of the short wedge” Boas (1909:483).

Wedges found in museum ethnographic collections rarely have associated information on their use. In the collection of the Royal B.C. Museum RBCM a Hemlock wedge (87843-2) is described by Charles Newcombe as having been “used by women with a small stone hammer for splitting wood for household purposes”. It was collected in 1904, on the north end of Vancouver Island. Newcombe gives the Kwakiutl name as “TlEmkyaia”.

An Ethnographic Example of a Wedge Set

A bark bag of an open twilled weave for holding wedges was collected with 6 yew wood wedges – four large and two small examples (RBCM2237A-g). It was collected by Charles Newcombe in 1912, from the northern Moachaht on the west coast of Vancouver Island (figure 14&15). Drucker later makes reference to a special woven bag to carry wedges (Drucker 1951:78).

Boas records that after chopping a small yew tree in pieces, the points or distal ends of these are “burned off to harden them, and are rubbed down with water on a large slab of sandstone. The burning of the wood prevents it from warping. When the point is ground down, the lower side of the wedge is given a steeper slant than the upper one; so that when driven into a horizontal log, the wedge is ground down on one side only (Fig. 51,b,c) [Examples are 47cm and 57cm long], and the sides are flattened down by chopping with an adze or by grinding. The tip of the wedge also generally tapers down from the sides. The butt-end is tapered down slightly, and is then provided with a ring made of cedar-withes. After the ring has been fastened on to the wedge, the butt-end is sometimes rubbed against a wetted grindstone until it is quite flat. Generally, however, it is battered down on a stone slab. Wedges for splitting boards are always made in sets of seven pieces, the longest of which is four spans long, while the others decrease in length to about two spans and a half or less” (Boas 1909:323).

Boas specifically mentions wedges made for hollowing out canoes: “These are made of crooked pieces of yew-wood, which are bent so as to conform to the inner curvature of the canoe. They are ground down to a point on the concave side.

Drucker (1950) lists wooden wedges as element #420 and includes element #421 as a “symmetrically tapered” wedge and element #422 as a “curved” wedge. He notes: “There are apparently two forms of curved wedges, used particularly in canoe making, but it was not possible to differentiate between them consistently” (Drucker 1950:255).

Boas indicates that small wedges are “used for work in the house, particularly for splitting firewood. These are only about 20cm long, and are generally ground down evenly from both sides, the point of the wedge being rounded.” The example he shows in his Figure 51a is 24cm long (Boas 1909:323).

Wedges from the Ozette Site

The excavation of the famous Ozette site on the Olympic Peninsula, buried in a mud slide about 400 years ago, resulted in the recovery of 1100 wooden wedges. This site provides us with the largest comparative sample. Wedges at this site were grouped into seven sub-types on the basis of morphology, cross section size, and length. There were 42 preforms (unfinished examples) at the site. Gleeson notes that “both wedge fragments and complete wedges with evidence of repair indicate steps used to maintain the wedges” (Gleeson 1980:67).

The Ozette wedges were made primarily from compressed spruce wood (Friedman 1975:121). Compression wood is cut from the underside of a leaning branch. Because of the stress on the moving branches, this wood has very thick cell walls and round cells in cross section. It is important to have the compression parallel to the grain to take heavy pounding.

The Ozette collection has a much wider range of wedge types than is reported in the ethnographic literature. Gleeson indicates: “it is supposed that the majority of the large cross section oval wedges were used for heavy duty splitting such as removing large blocks from standing trees or fallen trees, the rectangular wedges represent somewhat different approach. Because the oval wedges have their bit in the same plane as the thickness dimension, their lifting height is therefore equal to their width and not their thickness”. He refers to thickness as “lift” (Gleeson 1980:67).

Gleeson observes that oval wedges are symmetrical; the rectangular wedges are asymmetrical on the width axis, one side being straight and the other convex. This characteristic could work to advantage when splitting wide thin pieces of cedar that would be likely to develop secondary splits or fractures.

The “rod” wood wedges do not fit into the above descriptions: “The rod wedge is a long slender wedge almost circular in cross section. The proximal ends of these wedges are not grommeted and the distal end has more of a point than the convex margin of the other wedges” (Gleeson 1980:67).

The Ozette whole wedges and fragments were subdivided into large, medium, small, and marking (extra small) wedges. The four most numerous categories were large rectangular wedges, large oval wedges, rod wedges and preforms (Gleeson 1980:68).

Drucker indicates that the short wedges “are seen to be those that may have been cycled out of use, while the medium to long wedges are probably still usable. The groups of wedges are assumed to reflect the splitting of both different shapes and sizes of wood”. Length ranges three feet to several inches (Drucker 1951:78).

The Ozette sizes are as follows: Short large Oval: L. 10.0-25.8cm. Mean 17.4 SD 3.34. Width: 2.2-5.8cm Mean 4.0 SD.52. Thickness “lift”: 1.9-5.5. mean 3.1.SD .58cm

Medium to long. Large oval wedges; L. 26.1-64.5 Mean 37.2. SD 9.68. Width 3.5-5.5. Mean 4.6. SD.52. Lift 1.9-4.6 Mean 3.5 SD.77.

Gleeson indicated that 114 of the Ozette wedges still had grommets and the other 304 have battered ends Gleeson 1980). Although wooden wedges have a variety of shapes the antler wedges of Ozette have only one morphological variety. They are low angled dense short wedges that Gleeson believes were mostly likely used for starting splits. Whale bone rib wedges include one variety of broad flat wedges possibly used to split and support wide thin boards such as would be used for boxes (Gleeson 1980:62).

Gleeson inventoried 54 antler and two bone wedges: Elk base (1) whole beam (19) split beam (17) joint as proximal end (1) tine (1); and indeterminate tip fragment (16). Antler and bone L: 6.9-26.6 Mean 16.0 W: 2.1-7.2; Th: 1.3-5.6; bit angle 12-31 mean 20 degrees (Gleeson 1980:65).

Stern describes the use of wedges in processing a cedar tree. It is felled: “by cutting all around it with a sledge and an elk horn blade. … the tree is then trimmed and when the boughs are removed, it is split into halves by means of large stone hammers: both halves are used as material for canoes. Small bone wedges start the split at one end and after the crack is begun, wooden spruce knots are inserted as gluts. As the wedges open, short timbers catch all the slack and the working wedge is placed at the smallest part of the spit until the other end is reached.” After fires have burned holes at intervals inside the canoe, the section between the holes are hewn out with an antler wedge and hammer (Stern 1934:95).

Conclusions

An examination of Museum collections and descriptions in the ethno-historic literature indicate there is a wide variety of artifacts often labeled as wedges that have specialized uses as wedges as well as uses for purposes other than wood working wedges. What are the differences in the use of wooden wedges and wedge-like antler artifacts? A more finite description of those objects we find in archaeological sites and controlled experimentation with replicas in their use is needed to gain a better understanding of the more complex behavior behind these important processing tools.

References

Boas, Franz. 1909. The Kwakuitl of Vancouver Island. Jessup North Pacific Expedition. 5(2) 301 -522.

Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History, 8(2).

Boas, Franz. 1921. Ethnology of the Kwakiutl Indians. Thirty-Fifth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution 1913-1914. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC.

Drucker, Philip. 1950. Anthropological Records. 9:3. Culture Element Distribution: XXVI. Northwest Coast. University of California Press, Berkley and Los Angeles.

Drucker, Philip. 1951. The Northern and Central Nootkan Tribes. Smithsonian Institution. Bureau of American Ethnology. Bulletin 144. United States Printing Office, Washington.

Friedman, Janet Patterson. 1976. Wood Identification – An Introduction. In: Gerald H. Grosso (ed), Pacific Northwest Wet Site Wood Conservation Conference. September 19-22, 1976. Volume 2, Neah Bay, Washington, pp. 41-46.

Gleeson, Paul F. 1980. Ozette Woodworking Technology. Project Reports No. 3. Laboratory of Archaeology and History. Washington State University, Pullman.

Newcombe, Charles. 1904. Newcombe Family File. RBCM Archives manuscript 1077, Vol. 59, F14-1.

Sproat, Gilbert Malcolm. 1868. Scenes and Studies of Savage Life. London: Smith, Elder and Co.

Stern, Bernhard J. 1934. The Lummi Indians of Northwest Washington. Columbia University Press, New York: Morningside Heights.

Waterman. T. T. 1973. Indian Notes and Monographs No. 59. Notes on the Ethnology of the Indians of Puget Sound. Museum of the American Indian. Heye Foundation. Printed in Germany by J.J. Augustin, Gluckstadt.