Originally published in The Midden. Publication of the Archaeological Society of British Columbia, 25 (1), 3-5, February 1993.

By Grant Keddie

Prehistoric Dogs of B.C. Wolves in Sheeps’ Clothing?

Throughout the history of North American we see many varieties of native dogs. In British Colombia we find the Bear Dog of the Northern Interior and parts of the northern Coast used for hunting and packing, and a coyote-resembling dog of the southern Interior and Coast used mostly for hunting. On the southern Coast we also find what has become known as the Salish Wool Dog, kept mainly for the production of wool from its thick soft inner coat.

With the use of their hair to make of blankets and capes high in trade value, these dogs made an important contribution to the status of their owners. The origin of the dog is particularly interesting. Where did they come from, and how long ago?

In many parts of the world dogs have undoubtedly played a key role in the development of human hunting strategy and technology over the last 12,000 years. Based on anatomical and genetic studies modern domestic dogs stemmed from ancestors that also gave rise to wolfs, coyotes, jackals and foxes. The dog can interbreed with all but foxes and have fertile offspring.

The Asiatic wolf may be the best candidate as ancestor of the earliest domestic dogs; the other wolf sub-species (especially the northern grey wolf) must have been involved in genetic interchange with domestic dogs on a long-term intermittent process. How do we tell the difference between a wolf and a dog? Early domestic dogs are characterized by an overall reduction in size relative to wolves. Skeletons of dogs indicate shortening of the snout, proportionally wider palates of both the top and bottom of the mouth, the larger inner volume of the cranium of the skull, and some closely spaced or absent teeth.

Remains of what have been identified as domestic dogs occur in the Middle East from Israel to Iran dating between 12,000 and 9,000 years ago. In America the oldest domestic dog remains are found in Danger Cave, Utah dating between 9,000 and 10,000 years ago. Others include complete skeletons of dogs, obviously intentionally buried in a hunting camp at the Koster site in Illinois 8,500 years ago. Measurements of the dog components from the Koster site fall between the norms of modern dogs and coyotes.

One of the early varieties of domestic dogs is the spitz breed. Large spitz dogs ranging across the artic from the Samoyed of northern Europe to the Siberian husky, and Alaskan Malamutes and the Canadian Eskimo Dogs to the east. These northern working-dogs that have contributed to the genetic make up of, not only many modern breeds in Europe and Asia, but also the now-extinct dogs of British Columbia. One characteristic genetic trait of spitz breeds is the tail which curves over its back. This trait is regularly noted in early historic descriptions of the Bear Dog and Salish, Wool Dog in British Columbia.

NATIVE DOGS OF THE GULF OF GEORGIA/PUGET SOUND REGION

Of the two distinct types of native dogs found on parts of the southern coast of British Columbia and Washington State, one is clearly described as resembling a coyote. The other is the Wool Dog which resembles a cross between a small dog and a version of a northern spitz. Avrom Digance, a graduate student at S.F.U., has demonstrated that dog burials from Pender Island dating back about 2,500 to 4,300 years represent a single breed of domestic dog similar in bone structure to both dogs and coyotes today.

The first observations of Wool Dogs on the southern coast appear in 1792. Captain George Vancouver, while anchored near Restoration Point in Puget Sound, described the numerous dogs:

… much resembled those of Pomerania, though in general somewhat larger were all shorn as close to the skin as sheep…and so compact were their fleeces, that large portions could be lifted up by a corner without causing any separation composed of a mixture of a coarse kind of wool, with very fine long hair, capable of being spun into yarn.

In the Gulf of Georgia, other early explorers, Galiano and Valdez concluded that blankets they received from inhabitants of the north end of Gabriola Island were of dog’s hair, partly because when the: “woven hair was compared with that of those animals there was no apparent difference, and partly from the great number of dogs they keep in those villages, most of them being shorn. These animals are of moderate size, resembling those of English breed, with very thick coats, and usually white…”.

In the 1840s, while Alexander Anderson, passing the many palisaded villages on the lower Fraser River, also observed:

“ whole hosts of white quadrupeds, some shorn like sheep, others sweltering under a crop of flowing fleece The dogs in question are of a breed peculiar to the lower parts of Fraser’s River, and the southern portion of Vancouver’s Island and the Gulf of Georgia. White with long woolly hair and bushy tail, they differ materially in aspect from the common Indian cur, possessing however the same vulpine cast of countenance”.

John Keast Lord, the naturalist, suggested that these Wool Dogs:

“differing in every specific detail from all the other breeds of dogs belonging to either coast or inland Indians”, were kept on islands to prevent their escaping. He recorded that the Chinook of the Columbia River were the “first possessors of these white dogs…as far as it is possible to trace it”. Besides the dog “…used by the Skagit, Klallam, and others of the lower part of the Sound and Gulf of Georgia, which is shorn for its fleece…pretty good size, and generally white, with much longer and softer hair…but having the same sharp muzzle and curling tail…”.

Historian George Gibbs referred to a second type of dog which resembled a coyote and was used for hunting. In 1833, among the Nusqually in Puget Sound, William Tolmie purchased “a large woolly dog”, which his party killed and ate, as well as a “short haired Indian wolf dog breed”

Gibbs provided the native names “sko-mai” and “ska-ha” for the two types of dogs. Approximations of these names were given to James Teit by Cowlitz elders who described the “Kaha” as a “sort of grey wooly or thick haired dog straight ears, tail curled slightly used for hunting,” and the “Kimia” which is “about same size various colors browns and spotted whites they had finer longer hair and were sheared”.

In Spuzzum the woolly dogs, altogether different from the common dog of the Thompsons, were called by the special name of x lit silken. An elderly weaver told James Teit that the pure breed of Wool Dogs was totally extinct around Spuzzum from before she could remember, but that she had heard from the old people they were medium-sized dogs with long, very fine, thick hair. They were mostly white but some it is claimed were black. Though mostly white, some were black and their hair was also used for making blankets. Paul Kane had also described the Wool Dog as a peculiar breed of small dog with long hair of a brownish-black and a pure white hair. A distinct species, Wool Dogs were introduced from the Lower Fraser according to tradition, and found nearly as far east as Lytton. They were favoured around Spuzzum and were kept from interbreeding with the “real” Interior hunting dog. The skaxaoe (viz “real” dog) resembled the Husky and also bore some similarity to coyotes and wolves with which they occasionally interbreed.

There was a distinction in most central Coast Salish languages of at least two types of dogs – the common hunting dog and the woolly dog. In some areas the Wool Dog may also have been used for hunting, but such information was usually collected well after the extinction of the Wool dog. The names most commonly used for the two types are variations on sko-mai and ki-mia for the woolly dog and ska-ha or ka-ha for the common dog.

THE USE OF THE HAIR

Out on Vancouver Island Diamond Jenness recorded in the mid-1930s that:

“…Dog’s wool was not mixed with cedar bark or with goat’s wool; it was used for clothing – the women’s underskirt, and…a cape for a man. Not mixed with goat’s wool because this wool was not procurable until mainland Indians got guns and could shoot many goats”.

Yet Makah elders informed Erna Gunther at about the same time that Mountain goat wool was bought in Victoria through the Klallam, but that finished blankets were bought more often than the raw wool. James Teit, after the turn of the century, explained that at Spuzzum dog hair used in blanket-weaving was

“generally mixed with the wool of the goat. People who did not have any of these dogs used only goat’s wool. The using of dog’s hair it is said made the blankets of a softer texture and further more they supplied a source of wool right at hand, whereas the goats had to be hunted and their wool thus cost -considerable labor”.

Historical documentation notes that dog’s “wool” was mixed with many different materials for weaving. Along the coast in Bellingham Bay in 1857, E.C. Fitzhugh referred to people dressing in blankets made of dog’s hair and feathers.

John K. Lord noted that the long white hair of the dogs was annually shorn and then mixed with mountain goat wool, duck feathers or hemp. At Qualicum on Vancouver Island Aylmer mentioned winter garments consisting of blankets woven from various things, among them bark and dog’s hair.

The Quinault and Skokomish also mixed duck feathers and seed fluff to make blankets. Ethnobotanist Nancy Turner and ethnohistorian Randy Bouchard have recorded that the seed fluff of the Fireweed (Epilobium angustifolium) was mixed with dog hair by the Saanich, and with both dog and goat wool by the Squamish and most Puget Sound groups.

In 1847 Paul Kane described the process among peoples on the south end of Vancouver Island where in winter the men wear a blanket:

“made either of dog’s hair alone, or dog’s hair and goose down mixed, frayed cedar bark, or wild goose skin…dogs are bred for clothing purposes. The hair is cut off with a knife and mixed with goose down and a little white earth, with a view to curing the feathers. This is then beaten together with sticks, and twisted into threads by rubbing it down the thigh with the palm of the hand…after which it undergoes a second twisting on a distaff to increase its firmness. The cedar bark is frayed and twisted into thread in a similar manner. These threads are then woven into blankets by a very simple loom of their own contrivance”.

Bernard Stern, an ethnographer in the 1930’s among the Lummi, also recorded that the down of the swan and the eagle is worked into the coarse dog wool while it is being spun serving as a fleece. The finished blankets are of three kinds: the common blanket generally used as a garment, called sweqetl, measuring about one fathom wide and one and one-quarter long, the second used for bedding, called xwlaqas, measuring about one fathom wide and two or three fathoms long, and the third, qetsenang which is very long and made especially to be used as a medium of exchange or to serve as gifts during festivals, at which time also the other two types are sometimes distributed.

A pioneer in Washington in 1849, Samuel Hancock noted “a great many” dogs at Neah Bay, which the Klallam “regularly shear and weave the hair into blankets in a way peculiar to themselves, quite heavy; and very coarse”.

Not only Lord and Charles Bayley refer to the dying of the dog hair. Other reports as well indicate colouring of the wool. In 1825 John Scouler observed among the Makah on the Olympic Peninsula that people of Tatooch show much ingenuity in manufacturing blankets from the hair of their dogs. On a little island a few miles from the coast they have a great number of white dogs, which they feed regularly every day. From the wool of their dogs and the fibres of the Cypress [cedar] they make a very strong blanket. They have also some method of making red and blue stripes in their blankets in imitation of European ones.

Near Agassiz on the Fraser River, early in the 1800s Simon Fraser observed newly shorn dogs from whose hair were made rugs with stripes of different colours, crossing at right angles and resembling at a distance, Highland plaid. As late as 1862 the Makah made “blankets from dogs hair and cedar bark”, but by 1846 we begin to see the demise of the use of dog’s wool. At Port Townsend, Washington, Berthold Seemann observed:

“… They keep dogs, the hair of which is manufactured into a kind of coverlet or blanket, which in addition to the skins of bears, wolves, and deer, afford them abundance of clothing. Since the Hudson’s Bay Company have established themselves…English blankets have been so much in request that the dog’s hair manufacture has been rather at a discount, eight or ten blankets being given for one sea-otter skin”.

James Anderson noted that Wool Dogs

“…were regularly bred for the hair they furnished and were quite numerous even as late as 1849. With the increasing facilities for obtaining blankets & materials of European manufacture so the necessity for keeping up the breed disappeared resulting in the course of time in its total extinction”.

CONCLUSIONS

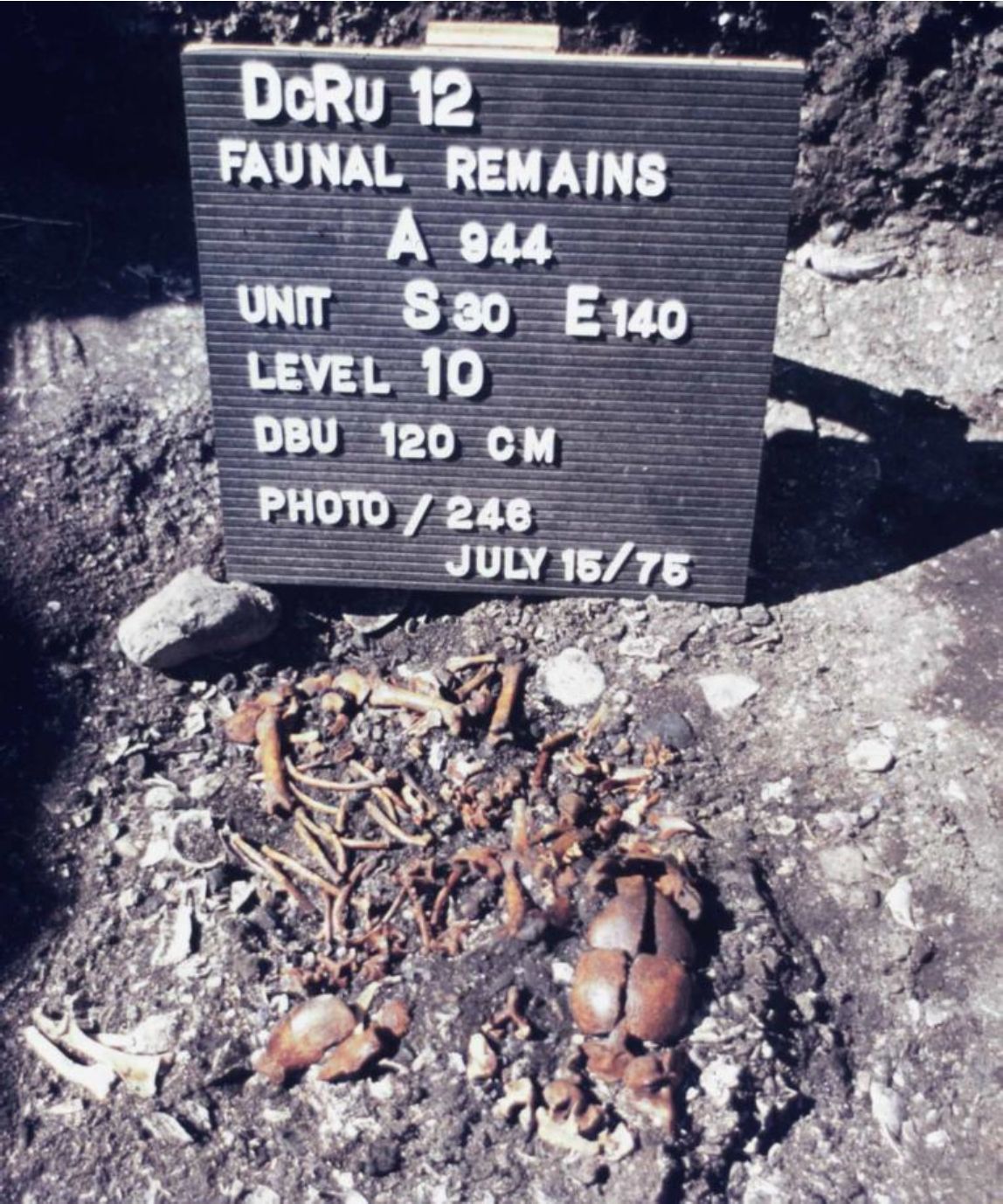

Much evidence exists in the historic record for the breeding of large numbers of wool dogs and their role in the weaving industry. But what about the prehistoric record? On southern Vancouver Island I have dated midden layers containing what I think are small wool dogs to a period beginning after 1500 years ago. In the same layers we find the first antler combs that may have been used as weaving tools, and the first spindle whorls and antler blanket pins. Is there a correlation between the introduction of the weaving industry and Wool Dogs?

This is just one of the questions that the fascinating study of the archaeological remains of native dogs might help answer. Undoubtedly the work of several researchers who are currently studying dog remains in British Columbia will help direct us.