Oct 19, 1999.

By Grant Keddie

Places are like magnetic beacons on the runway of life.

Humans are a product of the symbiotic interaction between mental and biological structures. Humans have developed a network continuum of symbolic features which some call “history”. History in this sense is like an umbilical cord to the world around us. Places provide attachments for the cord.

Animals perceive place from the perspective of maintaining their species or individual existence. This involves: (1) a sense of security from injury (physical and psychological); (2) getting food; (3) reproducing (passing on genetic or other information believed to be of value to genetic survival). [One or a combination of the above may supersede the others at any given time].

What are perceived by humans as higher forms of life, put out more complex “feelers” to the world around them, and move out over space accordingly. Some animals feed off the signals/experience of others of their species or different species (e.g. monkeys responding to bird warning signals). The social network extends the feelers of the individual, but this memory network is limited in animals that have not developed complex speech memory banks based on abstract thought.

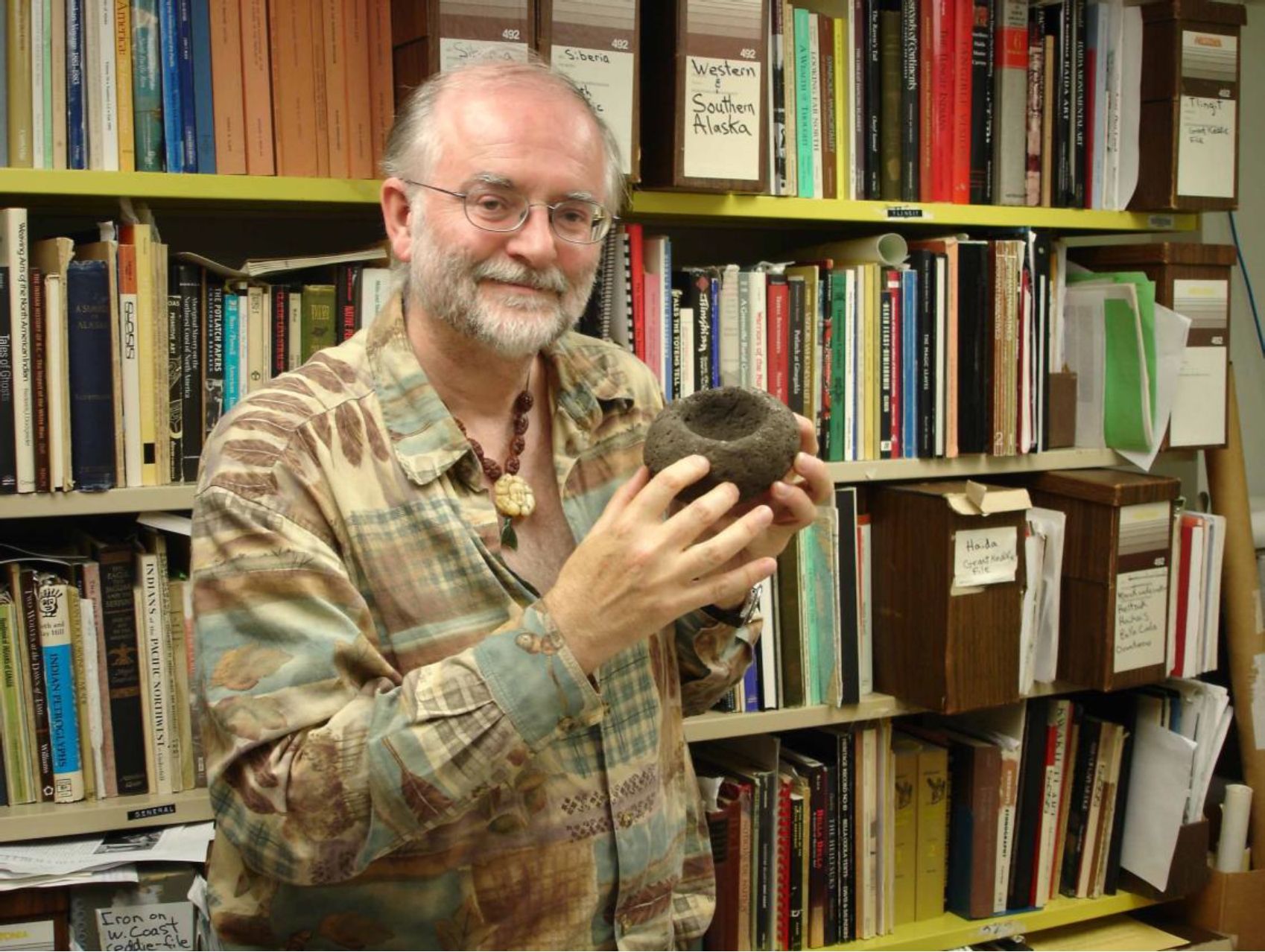

Humans, with more developed symbolic thought and its extension into writing, have developed histories of an oral and written nature that allow the extenuation of feelers operating from a larger data base of information and sometimes a diverse range of information.

Organisms not capable of abstract symbolism have sensing that depend on energy wave or chemical connections to the landscape around them. Some species can leave a signal (e.g. smell) on a place as an extended piece of information that defines what is happening in a larger area.

Humans can project inner abstract creations on the landscape or a place, giving it specific symbolic meaning. By modifying a place or maintaining reference to a location in oral or written history humans can assign a more complex meaning to the location to be taken up by future generations. This meaning may be similar to that of a urine stain or something more complex.

Symbolic histories allow humans to link places with a complex range of other (live or dead) people’s experiences, both “real experiences” and experiences that involve a verbally transmitted component of abstract symbolism.

It is likely through the synchronism of events that humans have assumed a cause and effect relationship linking human presence or human behavior (“physical” and “psychological”) to changes in the “external” world.

Humans learn to avoid or to control unexplained forces. Things seen as normal or common do not need explanation as much as things that do not seem normal – such as a large glacial erratic boulder on a flat plain or a whirl pool in a long placid stream.

Human cultures have always viewed the world in a scientific manner within the limits of their knowledge base. In traditional gatherer societies the observation of recurrent patterns would correctly tell where fish would be in relation to the tide line or where elk would be in relation to the sequence of the day.

When these normal patterns did not occur intervention that involved human behavior of both a “physical” and “psychological” nature (e.g. a ritual song with “magical” words) were implemented to bring things back on schedule.

Symbolic histories that have developed as survival techniques for humans may work for or against their survival in the same way as a chemical response in a “lower” organism. The effect of symbolic abstraction has allowed humans to diversify their environment (in the

larger sense of that word) and thereby promote the survival of the species on, at least, a short term bases. [The destruction of the Earth’s ecosystems and resources may reduce diversity before the expansion of radically new kinds of energy transfers that allow greater diversity].

The human development of a concept of the self (or more correctly, what H.G. Wells called the “illusion of the self”) has promoted greater diversity in the survival data banks of the species. This concept of the self can work both for and against the survival of the individual and the species, buthas tended to promote diversity for greater survival in the short term.

History is a high level of abstract thought that allows the species to go beyond its immediate experience in the quest for survival.

In humans there is a symbiotic relationship between biology and symbolic abstraction. The abstract symbolism thought process is as important to genetic survival as the human biological component. Because of the interactive relationship of biological and social experience we can saythat there is an interactive relationship between Place defining who you are and who you are defining place.

Human emotional (feeling; excited mental state) response to place: Individuals respond differently to levels of abstraction on the landscape – a city landscape may contain too much symbolism, creating stress – as opposed to an ocean shoreline landscape or a skyscape. The level of understanding and learned responses (related to security, etc.) determines the emotional response. [“Ignorance is bliss”]. The beach can be seen as a place to form close relationships between people or as a place to find food and fuel. [A woman from a fishing family who has lost her father, husband and sons to the sea, will have a very different experience gazing over the ocean waters than most land based people].

A place can create an emotional experience based on the combination of: (1) preconceived symbolism and emotional response or (2) A physical experience to do with human/place interaction. Factors such as openness, coziness or barometric pressure will play a role here. A state of “wonder” or an “aesthetic experience” may relate to less symbolism or more depending on its nature and its prescribed cultural associations (e.g. rainbows are good, eclipses are bad). Ones range of view (“physically” or “psychologically”) on perceiving a landscape affects one feelings of security. Being on a mountaintop can be viewed as safe or dangerous.

How we define ourselves and our perception (knowledge) of the world around us determines how we define place. Our emotional perception of place is based in part on our cultural experience or cultural symbolism associated with that place.

The view, or range of view, we have of the landscape affects are emotional state. Convolutions of the landscape define a level of security. You are safer where you can see dangers, or where dangers can’t see you. To some people lawns are safer than forests.

The more definable (understandable) the environment, the safer one may feel in the short term or less secure in the long term depending on the level of perceived control over the situation. One’s “defining” is based on the interplay between the direct physical senses and on symbolic projection.

Language defines landscape according to our use of it and defines levels of security. The imprints of the language then define how we respond to the place. You do not need to define a place you do not use – only in a general sense. The language of place may presuppose these names with good or bad connotations – “out there”, “outer limits”, “heaven”, “hell”.

Our concept of purpose defines how we respond to place. For some it is short-term physical survival – for others long term symbolic survival. Unique places – seen as “powerful” places can also be seen as places to gain control by directing that “power”.

Places become imbued with significance by repetitive ritual activity at a specific location. Places where significant events occurred bring feelings to the surface. The repeated references to those events at a particular place imprint the location with special significance. Places can bring people with common past or common beliefs together or to bring individuals together who perceive more emotional connections. Just as humans are drawn to empathy with other human beings they can project their personality into a Place as an object of contemplation when that place is “scented” with the same feelings. Over time the information about the place often changes to suit the power structures or beliefs of the current users.

The embodied knowledge of culture is lost when we alter the landscape around us. The discontinuities with places of the past places are ways of knowing at risk. Knowing our place allows us better placement of the magnetic beacons on the runway of life.