2005.

By Grant Keddie

INTRODUCTION

Kwah was a famous nobleman in the history of the Nak’azdli people of Stuart Lake in central British Columbia. Many of Kwah’s descendants continue to live in the region today.

According to oral histories of the Nak’azdli First Nation, Kwah was the first person in the region to own an iron dagger. Kwah and his dagger figure prominently in a number of significant historical events, particularly in a story surrounding events in the life of a young man named James Douglas – who later became the governor of the Colony of Vancouver Island and the Colony of British Columbia.

The events surrounding Kwah’s dagger forced the movement of Douglas to Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River. This move led to Sir James Douglas playing an important political role at a crucial point in the development of what is now British Columbia.

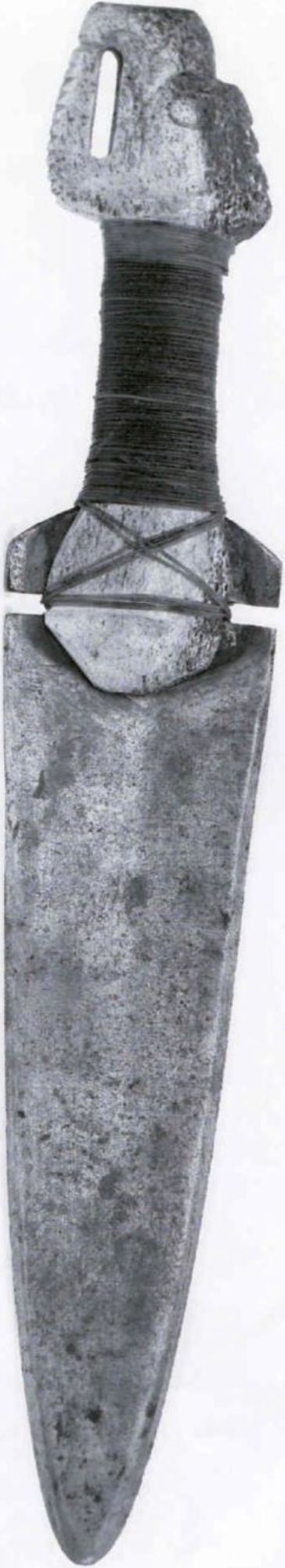

In the anthropology collections of the Royal B.C. Museum is a knife with an iron blade and a carved whalebone handle (RBCM, Ethnology col. #13345). Initially thought to be of Tlingit provenance based upon the handle design, artifact #13345 has now been identified as having belonged to one of Kwah’s descendants, Chief Louis Billy.

Could this dagger be the famous Kwah’s dagger known in the oral history of the Nak’azdli First Nations?

The following is an investigation into the history and analysis of artifact #13345 and the stories surrounding Kwah’s dagger. The process of clarifying the past ownership of artifact #13345 entailed developing an overview of daggers in a number of museum collections as well as historic accounts of knives in general.

In addition, the events associated with Kwah and his dagger span the period of time from both pre-European contact and post-European contact in northern BC (late 1700’s). This provided a unique opportunity to use modern scientific methods to help identify what is, or what is not, likely to be the original Kwah’s dagger and to see if we could find a way to date iron as a means of establishing its early presence in the province.

This research project was to be focused particularly on Kwah’s dagger, but of necessity it developed into an overview of daggers in museum collections (see appendix II) and a summary of the literature pertaining to 18th century trade in iron along the coast of British Columbia; the movement of Iron across Canada from East to west; as well as around the Pacific Rim. This detailed information has been summarized in a separate report, THE EARLY INTRODUCTION OF IRON AMONG FIRST NATIONS OF BRITISH COLUMBIA.

NAK’AZDLI ORAL HISTORY OF THE INTRODUCTION OF IRON

Oral traditions of the Nak’azdli pertaining to the introduction of iron tools were recorded in the late 20th century by Rev. Adrian Morice. It is important to look at the details of this information to gain an understanding of the timing of the introduction of iron utensils into northern British Columbia.

Morice was told that a man named Na’kwoel from Stuart Lake was the first person to acquire an iron blade for a woodworking adze. His grandson Kwah was the first person to acquire an iron knife.

Na’kwoel (c. 1660-1765), obtained his adze about 1730 at the village called Tsechah – located close to what is now Hazelton on the Skeena River. Tsimshian traders – who were said to have received it from ships on the North Pacific – brought the knife up the River. However, there are presently no documented activities of non-aboriginal traders off this part of the coast until the end of the 1700s.

The Nak’azdli told Morice that Na’kwoel’s iron adze blade was acquired at a ceremonial feast, where it was hung from one of the lodge rafters for the guests to view. It’s possession served to enhance Na’kwoel’s prestige among people of the region.

[Iron objects have been found in archaeological excavations at the Chinlac Village site near the confluence of the Stuart and Nechaco Rivers (Borden 1952). Could these objects be the same age as Na’kwoel’s adze?]

Morice was told that Chinlac village was attacked and devastated by the Chilcotin about 1745. The chief of the village Khadintel, was absent during the attack. Khadintel set out on a revenge raid three years later with a few survivors from the old Chinlac village and allied villages at the north end of Stuart Lake, Stony Creek and Fraser Lake.

The Nak’azdli told Morice how they attacked and devastated the Chilcotin village at Anahem. The survivors of the Chinlac massacre later settled among relatives at Tache, at the north end Stuart Lake, and at Lheitl near Fort George (see Note #1).

Kwah and His Dagger

After the Chinlac massacre, about 1780, the Nazko from Blackwater River attacked and killed most of the people at a village above Hay Island on the upper Stuart River. The chief’s 15-year-old brother Nathadlhthoelh (Mal-de-gorge) escaped. Two of his sons on a hunting expedition at the time were Kwah, about 25 years old, and Oehulhtzoen about 22. Kwah’s mother was the daughter of Na’kwoel, the owner of the first iron adze.

The Nak’azdli told Morice that when Kwah became a duneza (nobleman) he chose the title of his maternal uncle A’ke’toes (1st son of Na’kwoel). Kwah was known as the first man to own an iron dagger among the Nak’azdli. Kwah held a potlatch to pay for the dagger, which he received from a duneza living at Hagwilget on the lower Bulkely River about 1775 (Morice, 1904).

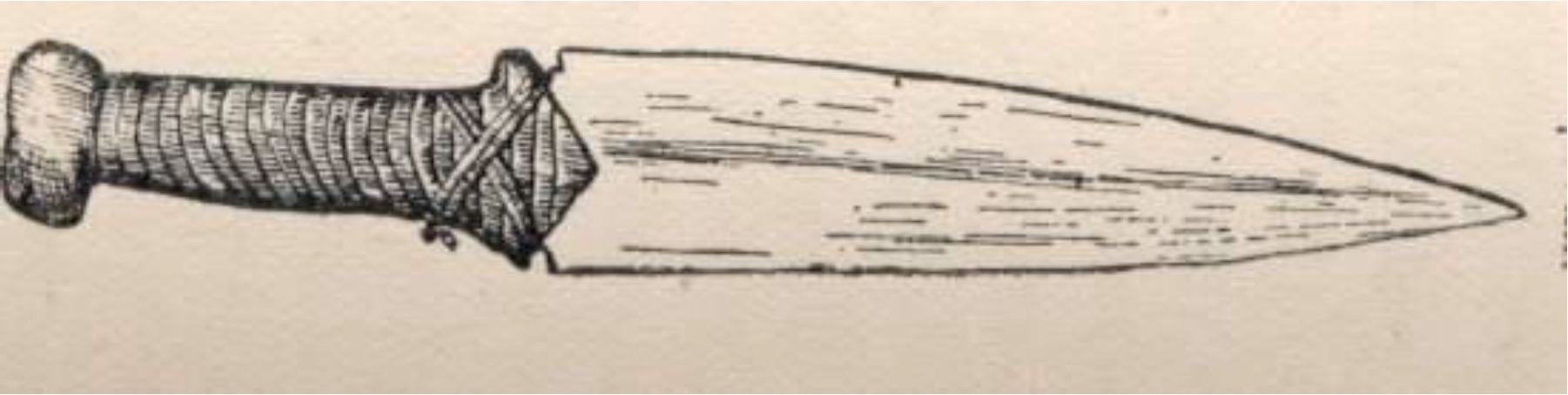

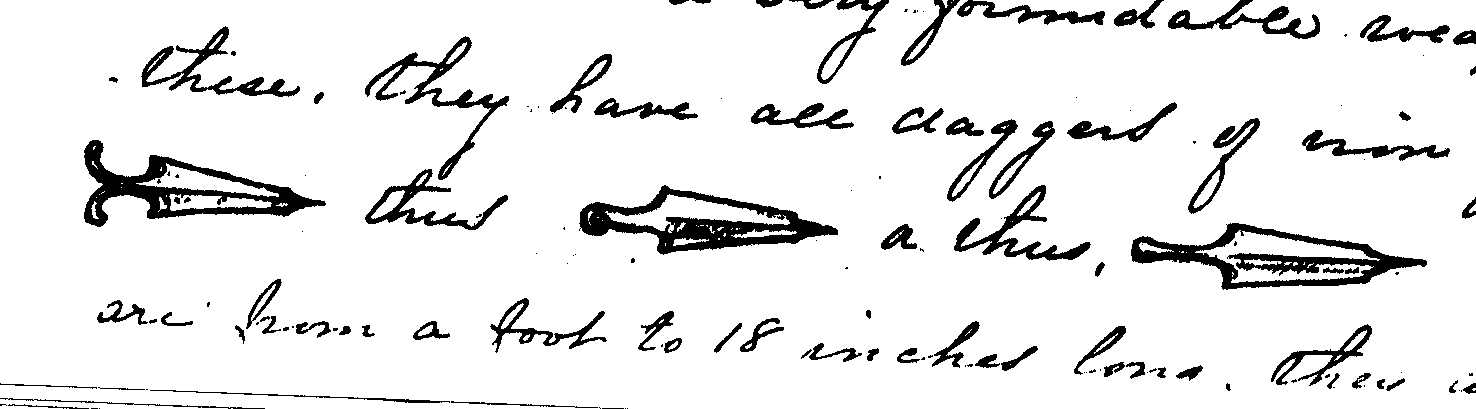

About 1782, Kwah took revenge on a Nazko village. He chased a man named Ts’oh Dai and killed him with his iron dagger. Morice, recording the story in the 1890s, pointed out that the dagger used by Kwah was “still in the possession of one of his sons at Stuart Lake” (Morice 1904:25). Morice has the same drawing of “Kwah’s dagger” in his 1894 (p.142) and 1904 (p.25) publications.

Morice recorded that Kwah had a friend whose father (Utzi-lla-e’ka) possessed an iron axe which, at the time, was “still exceedingly precious” in the Stuart Lake area. Kwah’s friend lost his father’s iron adze in a gambling game at Tache village. Kwah later killed Utzi-lla-e’ka who blamed him for losing the iron adze. I would suggest that Kwah would be at least 20 years old at this time and lacking his own iron dagger. Utzi-lla-e’ka may have had his iron adze about 1760 – 1770.

Kwah’s Dagger and James Douglas

Kwah’s dagger became famous in the Euro-American community because of an incident that involved Sir James Douglas, when he was a young clerk at the Hudson’s Bay trading post at Stuart Lake.

In 1828 an aboriginal man named Zulth-nolly, who was involved in the killing of two Hudson Bay employees five years earlier, was found visiting the local village while chief Kwah was away. Douglas’s men killed Zulth-nolly. This resulted in Kwah and his men coming into the fort where they disarmed and tied-up James Douglas until he promised to provide trade goods that were required to appease Zulth-nolly’s relatives. Under local custom, Kwah, as the village head, was responsible for protecting Zulth-nolly.

Several exaggerated versions of the incident suggest that Kwah’s dagger was about to be used by one of his men to kill Douglas, but Kwah intervened and saved Douglas’s life. There are a number of versions of the incident between Kwah and Douglas. The history and relationship of these stories is presented in Appendix I.

The Recent History of Kwah’s Dagger

The oral tradition states that Kwah passed the dagger to his fourth son, Daya or Moise, who turned it over to his brother Uts’oolh (also named Gooznal and Augustine). It then came into the possession of chief Louie Billy.

Lizette Hall, daughter of chief Louie Billy, sent a letter to the Royal B.C. Museum on June 22, 1998 explaining the more recent history of the dagger:

“Towards the end of his life Gooznal gave the dagger to my father, with these words. ‘I believe you will be able to look after your grandfather’s dagger, so I am putting it in your hands’. Later, the dagger was loaned, I believe to the Hudson’s Bay Company in Winnipeg. After this, my father became friends with Dr. J. B. Munro the Deputy Minister of Agriculture from Victoria. Dr. Munro helped my father get the dagger back. Sometime later, Mr. Munro came around for a visit. He and my father made a verbal agreement (in my presence) that Mr. Munro take the dagger back to Victoria to guard it. They agreed that if he (Mr. Munro) died first it would be returned to dad, should my dad die first, the dagger would stay in Mr. Munro’s keeping.

Waiting a reasonable length of time after Mr. Munro’s death, and not hearing anything, I wrote for my father to a mutual friend, Mr. Bruce McKelvie about this dagger and the agreement. Mr. McKelvie answered and he presumed it was in safekeeping and sent us Mrs. Munro’s address, and so I wrote for dad to the lady [Lillian Munro] regarding the dagger and the agreement with her late husband. She wrote on January 25, 1957 that everything was in storage. She said the terms of the agreement would be carried out when she got the dagger out of storage. This is the last we heard of K’wah’s dagger”

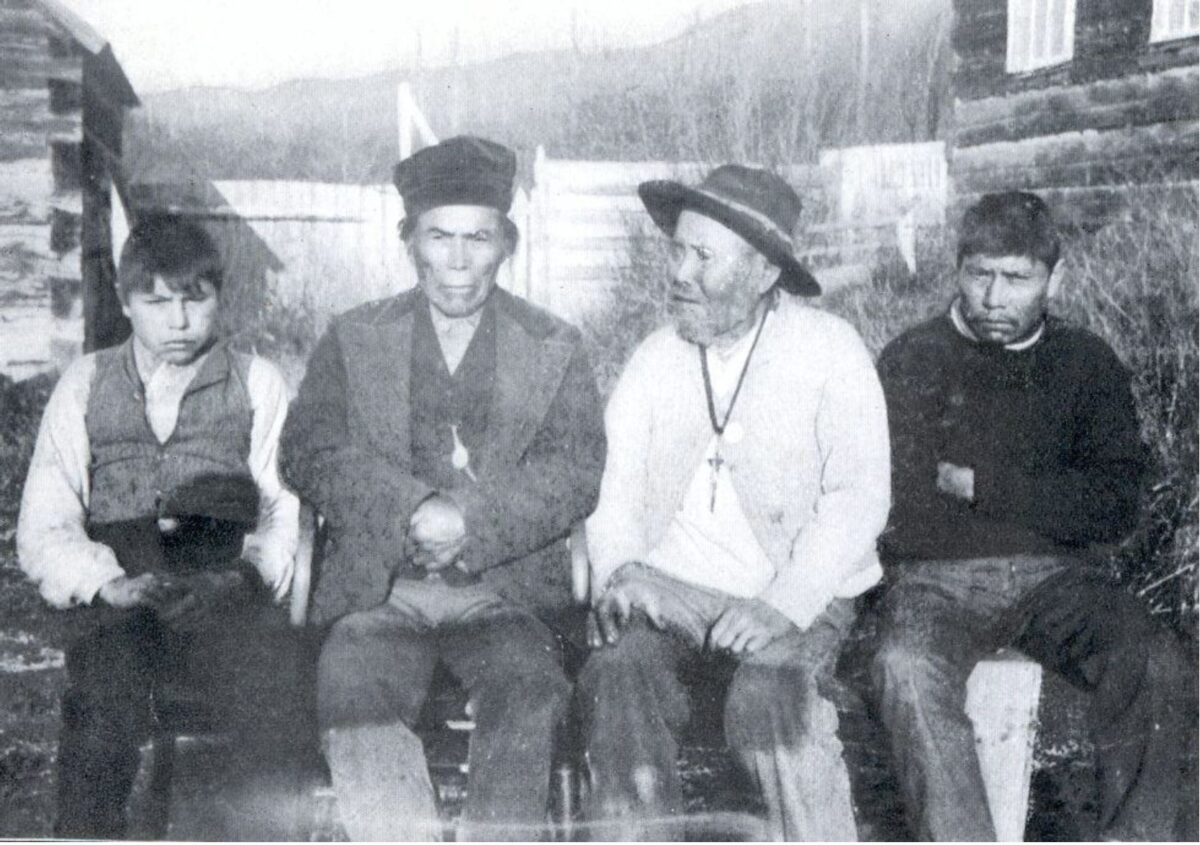

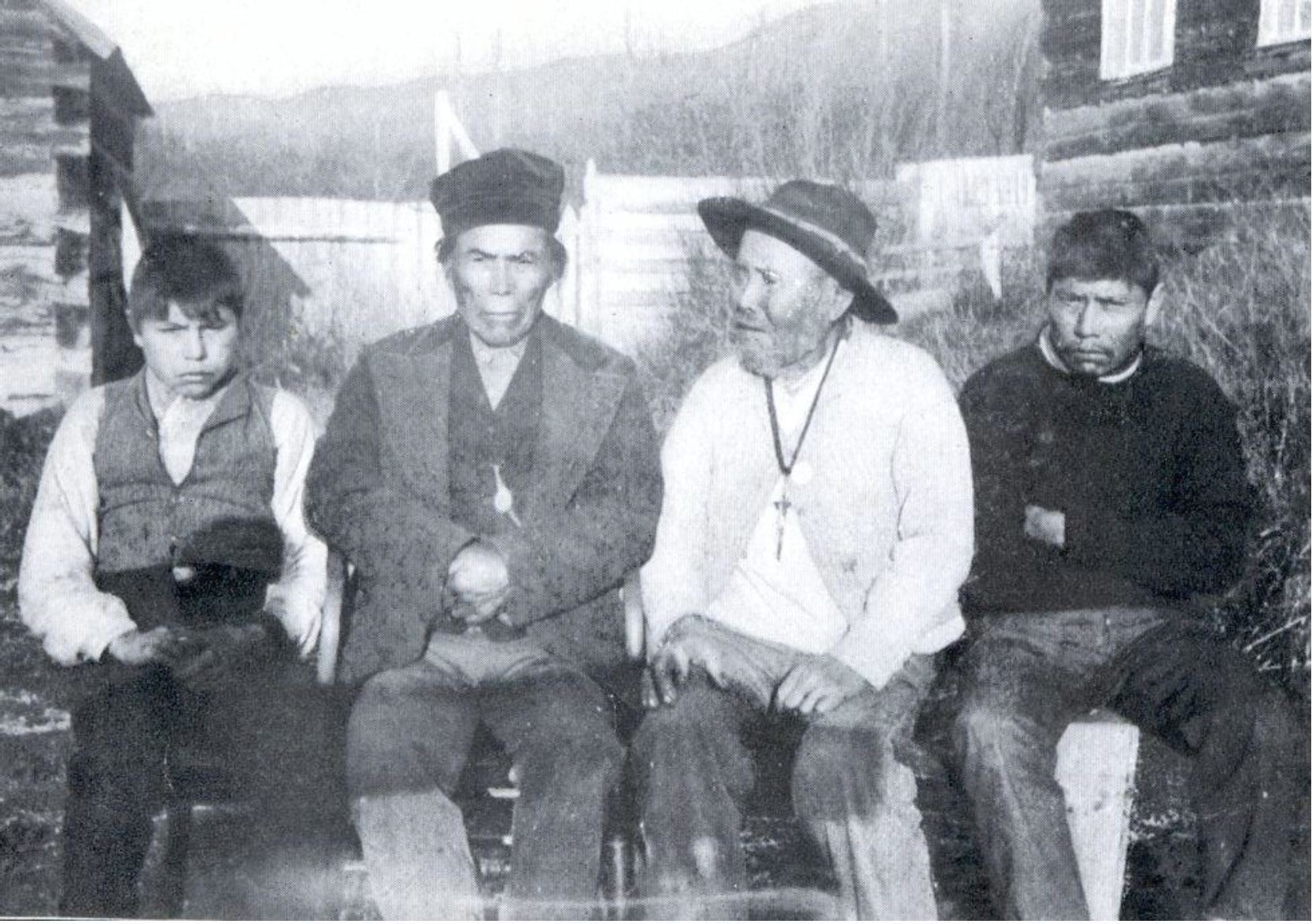

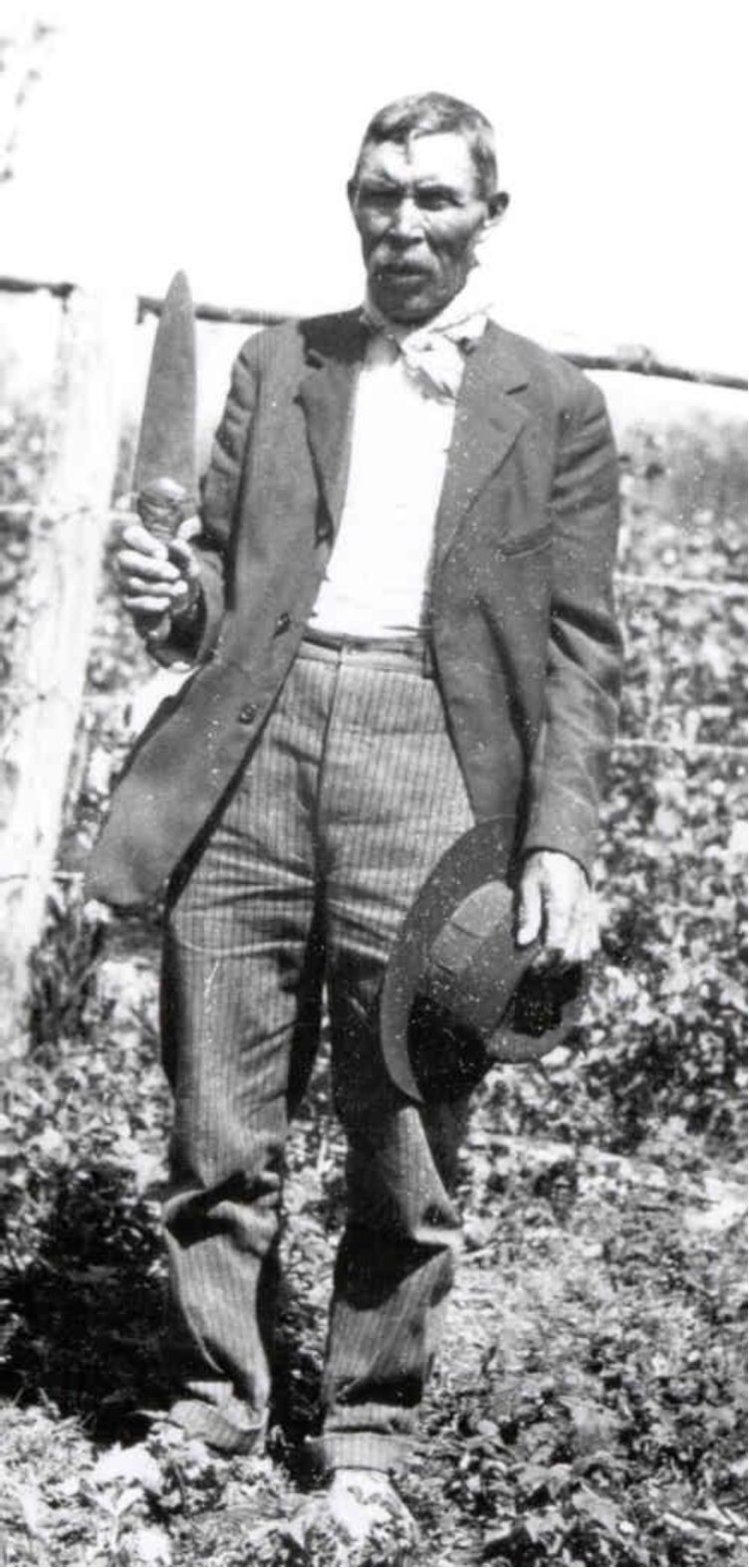

John Munro first met Chief Louie Billie Prince in 1926 and visited him on many occasions. Munro had probably read Morice’s 1904 account of Kwah’s dagger and was interested in seeing it. An anonymous photograph of Chief Louis Billy (RBCM, PN8580) shows him holding Kwah’s Dagger in July of 1926 – possibly this photograph was taken as a result of Munro’s visit.

Chief Louie Billie Prince visited Winnipeg in 1920, when

the Hudson’s Bay Company celebrated the 250th Anniversary of their establishment. A photograph of First Nations chiefs in Winnipeg – that includes Chief Louie Billie Prince – is shown on page 2 in Lizette Hall’s book (1992). I located a related photograph in the Royal B.C. Museum collections (PN11953). It is a copy of an original that has written on the front: “Indian Chiefs from Northern British Columbia visiting Head Office Union Bank of Canada, Winnipeg”. The chiefs from different areas of eastern central B.C. include “Louis Billie” and “George Prince”.

Lizette Hall was correct – the records provided to me by Katherine Pettipas of the Manitoba Museum shows that the dagger was loaned to the Hudson’s Bay Archives in Winnipeg. The information with HBCA accession No. 2283 states:

“The Kwah Dagger borrowed from Robert Watson in June 1928 from Chief Louis Billy Prince for the Company’s Historical Exhibit – returned in 1937”.

I knew that Robert Watson had acquired the dagger because on November 4, 1934, The Daily Colonist of Victoria had a feature article titled “Kwah’s Dagger”. It shows a fanciful First Nations wearing a Plains style ceremonial headdress and holding a dagger. Below this is a drawing labeled “Kwah’s Deadly Dagger”. I knew that the author of the article, Robert Watson, had been to Ft. St. James in September of 1928, because he wrote a first hand account about the Sir George Simpson Centennial held at the Fort. Watson must have visited the Fort earlier in the spring and confirmed his acquiring of the dagger in this article:

“On a visit several years ago to Fort St. James, the writer saw and held is his hand the famous Kwah dagger …and after a persuasive conversation with Chief Louis Billy Prince, who possessed it, he had the satisfaction of bringing it back with him”.

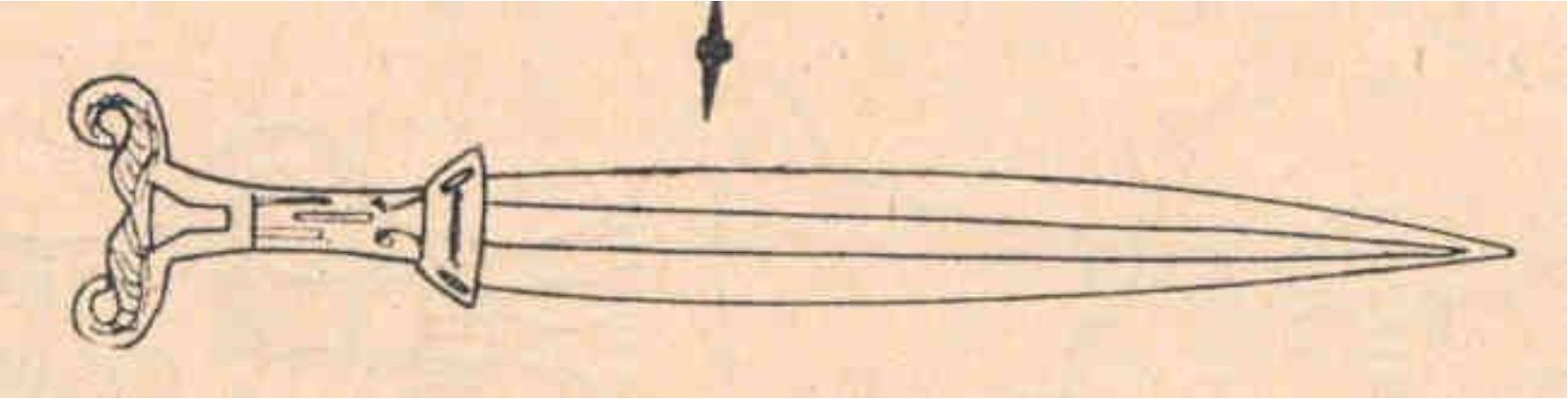

The drawing of the dagger shows a similar shaped blade to the 1894 and 1904 knife drawings in Morice’s publications, and a later photograph of the one once in the possession of John Munro – but the end of the handle in the Morice drawing is knob shaped and the 1934 drawing has a rounded piece at the end of the handle. I would suggest that the drawing in Morice was meant to represent the dagger, as it once was – not as the one then in the possession of one of Kwah’s sons. Morice states:

“Below, the reader will also find figured a steel dagger which came into the possession of the Carriers some 110 or 120 years ago …It was …originally much larger. The handle was also of a different description, the knife being one of a class of steel daggers called in the dialect of the Babines t’jak-nanist’ser, or ‘rounded at the end’ (of the handle). It probably resembled the instrument represented by fig. 108 e of Niblack’s”.

This figure in Niblack shows a round disc-like end on the handle – I think there is an attempt to copy this into the design of the dagger drawn for the 1934 newspaper account.

The Return of the Dagger

In 1938 Bruce A. McKelvie wrote about the return of the dagger:

“Chief Louis Billy Prince, the aged councilor of his people mourns no more and head chief Thomas Julian wears a glad smile. The reason for this happiness in the tribe is in the fact that Chief Quaw’s dagger has been restored to the custody of Chief Louis Billy Prince, its guardian. It was nearly ten years ago that a white man ‘borrowed’ the ancient weapon. It disappeared. Several years ago Chief Louis Billy Prince told his great friend, J. B. Munro, deputy minister of agriculture, of the tribal loss. [Munro] .enlisted the aid of Rev. Father Morice, .and of the Hudson’s Bay Company officials at Winnipeg, and as a result, the bloodstained blade was located .and has been duly restored”.

We can conclude that Robert Watson obtained the dagger from Louie Billie in the spring of 1928 and loaned it for exhibition later that year. It remained in Winnipeg and was not returned until about December of 1937. Dr. John Bunyan Munro, who had visited Louie Billie Prince on several occasions, obtained and returned the dagger to him with the help of Father Morice – who lived in Winnipeg at the time.

At a later date, Louie Billie must have loaned Munro the dagger for safekeeping – under the conditions explained by his daughter Lizette in her letter of 1998.

In the September 1943, W. P. Johnston noted in a newspaper article that the dagger was “now” in Munro’s possession.

John Munro must have deposited the dagger in the British Columbia Archives between 1939 and 1943. In his 1945, Doctoral thesis Munro indicates:

“Kwah owned the first iron dagger ever to appear among his tribe. It has been in the possession of Kwah and his descendants for two hundred years and is now in safekeeping in the Parliament Buildings at Victoria”.

At this time both the Provincial Archives and Provincial Museum were in the east wing of the Legislative buildings.

In an earlier manuscript version of his thesis [Kindly donated to the RBCM by James Munro on September 25, 1998] Munro indicates that the dagger “is now in the Archives at Victoria”. The fact that Munro had crossed out the statement in his earlier manuscript that the dagger “is still in the possession of Chief Louis Billy Prince” (p. 141), strongly suggests that he had acquired it recently.

Munro went on to say:

“For many years Chief Louie Billie Prince, …was the guardian of this famous weapon, but he found some difficulty in retaining it due to the eagerness of souvenir hunters. He worried over its safe-keeping when absent from his cabin on hunting and trapping expeditions”.

Rediscovering Kwah’s Dagger

A key sentence in John Munro’s thesis caught my attention:

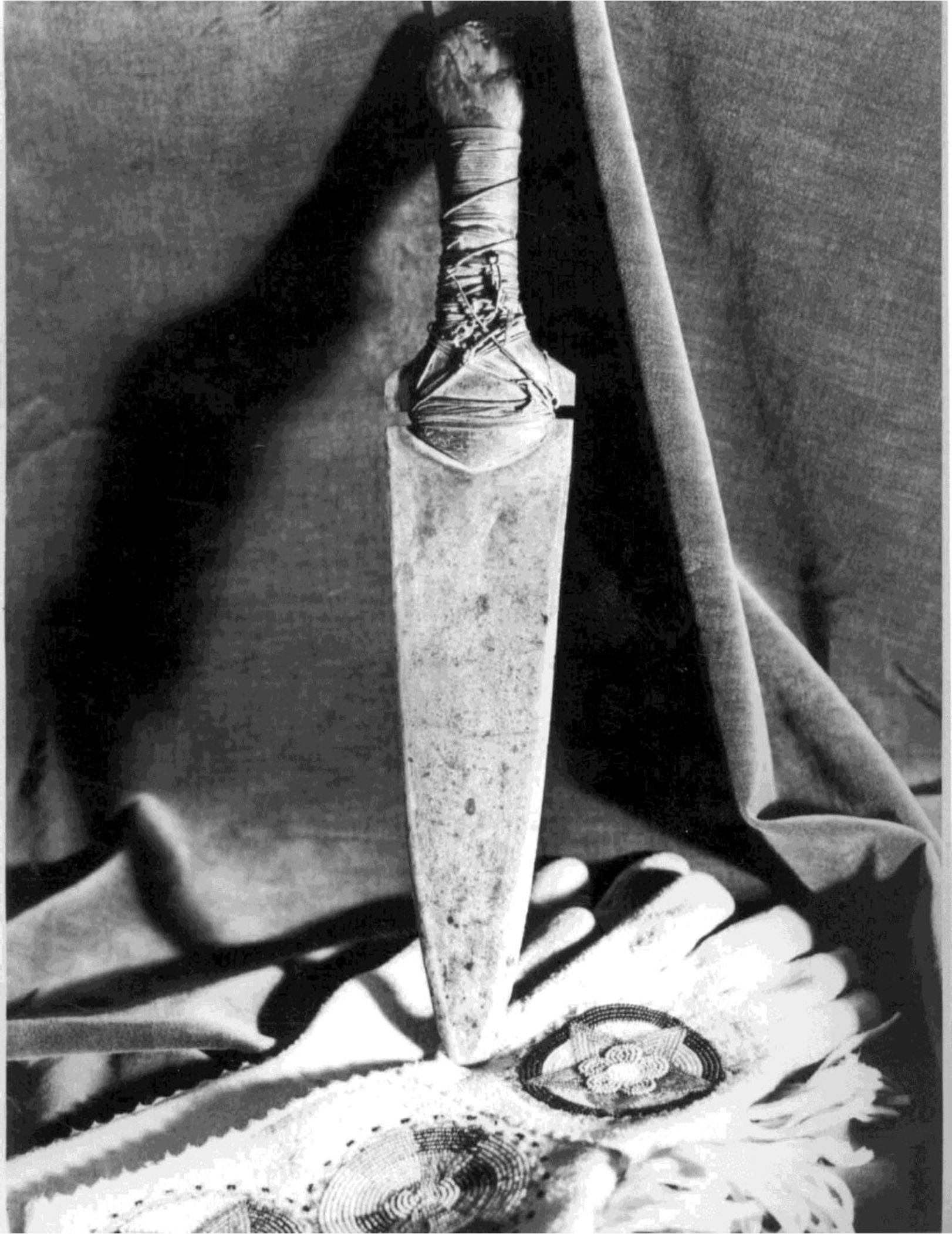

“For many years it served as a knife and was occasionally fitted into a long pole and used as a spear. In later years, it has had an artistically carved whalebone handle”.

After first reading this, it became clear to me that the dagger in the Royal B.C. Museum – #13344, was likely the one once in the possession of Louis Billy Prince.

I contacted the, now elderly, son’s of John Munro – James Munro and G. Eric Munro. They saw the knife with the older plain handle in the old Museum basement in the Parliament buildings and thought it was likely donated before the 1940s. Eric Munro kindly loaned me an original photograph of the dagger. The photograph shows the dagger with its earlier 1920s handle. A comparison of this photo with RBCM specimen #13345 clearly shows in detail that the latter has the same blade as the Louis Billy Prince dagger. The handle on the photograph dagger, however, shows a mark that is either indicative of a loose handle or a mark caused by an even earlier handle? This observation may support Morice’s contention that there was once an even earlier handle on the dagger.

There is some uncertainty as to whether John Munro eventually received permission from Chief Louie Billie to donate the dagger to the Museum. In an essay of Eric Munro, John Munro’s grandson, he states that (shortly after 1945):

“It was at this point in time that Dr. Munro asked the Chiefs permission to present the dagger to the Provincial Museum where it could be on display to the advantage of all to see.”

In 1998, Lizette Hall was sent a xerox of a photo of artifact #13345 – the Louis Billy dagger with the new handle. She said:

“Now the picture of a sword you sent me. That is not the picture of my great grand-father’s sword. …Both my 85 year old brother Solomon and I know what Chief Kw’ah’s dagger looks like. I saw it in the museum in November 1959 under a glass case. There was identification on it. I know it was Kw’ah’s dagger.”

The Royal B.C. Museum accession records indicate that the dagger #13345, was turned over to the Museum July 21, 1972 by the Archives. The information recorded states:

“Presented to Dr. J.B. Munro, B.C. Dept. of Agriculture who presented it to Archives who presented it to Prov. Museum”.

The original Provincial Museum catalogue description was “Tsimshian or Tlingit. Dagger – iron blade, flat, with carved whalebone handle, Blade attached to Handle with gut”. The designation as “Tsimshian or Tlingit” was based solely on the artistic style of the handle.

The new handle of this dagger was put on sometime between its return to Nak’azdli in 1937 and its being brought to Victoria before the end of 1943. The dagger observed in 1959 by Lizette Hall may have been one similar to the older version of the Louis Billy Prince dagger. Specimen 2912 is an iron dagger from Fort St. James that was collected by surveyor Frank Swannell and donated to the RBCM in 1917. The end of the handle on this specimen has a knob similar to that shown in the Morice drawings. The age and history of #2912 is unknown.

The question of the dating of the new handle and its location was resolved with the observation of an original photograph owned by Lillian Sam, of Nakadzli. The photograph clearly shows Lillian’s grandfather, Chief Louie Billie Prince, holding the dagger with the new carved whalebone handle. A Prince George photographer took the picture in the early part of 1943. It was likely just after this photograph was taken that Munro brought the dagger to Victoria.

After all this detective work, I finally found a 1969 letter from G. Clifford Carl, then director of the Provincial Museum, addressed to Clifford Wilson who worked for The Beaver Magazine of the Hudson’s Bay Company. This letter clearly filled in the time gaps in the recent history of the dagger. Carl stated that he consulted with the archivist Willard Ireland who said the dagger was “turned over to the Provincial Archives some years ago by Dr. J. B. Munro … It is now on display in the Forestry Exhibit in the rotunda of the Parliament Buildings”.

Subsequent to this letter, Bob Griffin, the Museum’s manager of human history provided me with a 1964 list of archives “Bayonets, Daggers, Swords, etc.” that was later turned over (except one) to the history collection. The one item on the list, #96, was the dagger “presented to Dr. J.B. Munro” and noted as being “Loaned to Forestry Display”.

So it appears that, when Lizette Hall visited the Legislative Building in 1959, the dagger now catalogued as RBCM #13345, was on display and probably labeled as being Kwah’s dagger. It was not in the Museum exhibit but in a special Forestry display in the Legislative rotunda.

Comparative Analysis of Daggers & Knife Types

We have now established that the RBCM dagger number 13345 is, in fact, the dagger that was once in the possession of Louis Billy prior to the 1940s. But is this the original dagger owned by Kwah? What can we tell about the age of this dagger by its physical structure and chemical composition?

Knives were made by Europeans and Americans in their home countries, and by their own armourers on board their trading ships. Some aboriginal peoples made their own knives from copper and some by modifications to European wrought iron. Things changed substantially when some First Nation individuals leaned to forge iron. Our current knowledge of what types were made by whom is in need of a serious synthesis beyond the scope of this paper.

Ferdinand Von Wrangell, made significant observations when writing in the c. 1830-38 period about the people on the Copper River of S.E. Alaska. The people of Copper River traded with the Tlingit to the south and the Tanaina to the north. They called the Russians ketchetnyai, from ketchi, the word for iron. Before the arrival of Europeans they used the local copper to hammer out hatchets, knives and breastplates for themselves and to sell:

“Nowadays they have become the only blacksmiths who know how to forge iron which they obtain from the Russians; neither the Kolosh [Tlingit] nor other peoples in the colonies know this art”. (VanStone,1970:5).

I examined descriptions and drawings in 18th century journals and daggers in museum collections to gain an understanding of the types of trade knives that were extant at various time-periods. I then searched out archaeological examples that where found in a context that suggested they were associated with the early trade contact period or of a possible pre-contact age. I found that knives in Museum collections often tended to be ascribed to time-periods earlier than the evidence allowed.

It was difficult to place many knives in distinct groups with shared characteristics. I have included here (APPENDIX II) an overview of a few general types that have been recognized in the literature. Chief Louie Billy’s dagger is what I define as a later period notched knife.

Metalurgical Analysis

I investigated ways in which it may be possible to date daggers by metallurgical analysis. Could the dagger of Louis Billy (RBCM #13345) be dated before or after a certain time period?

One method of analysis is Metallographic examination. This involves studying the techniques employed in the fabrication of metal artifacts (for details see Appendix III). A polished etched surface of a section, cut from an artifact, is examined under an intense reflected light source to observe grain size and other features. This examination reveals the internal structure of the metal, providing information on the thermal and mechanical treatments to which the metal has been subjected. The surface structure can tell us about chemical composition and serve as a general dating tool.

What I needed was precise data on the composition of a knife that would assist in identifying either specific time-periods or a geographical source for the raw material. Information on both these topics can be obtained more readily from the chemical analysis of the metal artifact.

One purpose of chemical analysis is to determine the concentrations of major elements (greater than 2%), minor elements (2 % to 0.1 %) or trace elements (less than 0.1 %) that can serve as a dating tool or source indicator. In some traditional techniques, element percentages need to be estimated and no one method of analysis will operate over a wide range for all the elements in the periodic table.

Knowing what elements are important in an analysis that can act as a dating tool, usually requires a large existing database that includes a wide range of elements produced from iron and steel of a known production date. A prime consideration in museum specimens that are to undergo metallographic or chemical examination is the amount of damage to the artifact that can be permitted. Taking a thin cross-section or a tapered slice of an artifact are destructive processes.

Dating Louis Billie’s Dagger

In researching the history of metals found in iron, I concluded that one element would be useful as a good time indicator for my purposes – manganese. Manganese was discovered and named as a substance by Carl Wilhelm in 1774. When manganese is added to steel, it forms hard steel that is very resistant to shock. Although some experimentation using manganese occurred as early as 1827, it was not until 1839 that a patent was taken out for the use of manganese in steel production and not until after the mid 1840s that steel production involved the use of manganese in any significant way.

Studies on metals dating from ancient times until the 1840s, and iron dating after the 1840s that did not have manganese as a deliberate additive, consistently show very small trace amounts of manganese, usually in the .04% or less range.

In order to get a precise answer on manganese content, and by minimal destructive means, I went to Kevin Telmer at the University of Victoria’s School of Earth and Ocean Sciences. In his aqueous geochemistry lab, Telmer uses a technique known as laser ablations inductively coupled plasma (ICP) mass spectrometry that can analyze microtargets as small as one-tenth the width of a human hair.

The laser ablation microprobe directed an intense laser beam onto a tiny fragment from the edge of the dagger. The target point gave off a puff of dust, which was then carried away by a stream of argon gas to be analyzed by a mass spectrometer. The results provided information on the content of manganese and many other elements. The dagger owned by Billy Louie was shown to contain 0.3% manganese.

Conclusions

The Royal B.C. Museum dagger #13345,is the dagger once owned by Chief Louis Billy. A new handle of whalebone, carved with a Tlingit-like design, was attached to the dagger sometime between 1937 and 1943. It was presented to the British Columbia Archives about 1943 and later placed on a long-term loan for a forestry display in the Rotunda of the Legislative buildings.

The proportionately large amount of manganese found in the iron blade of Louis Billie’s dagger clearly indicates that the dagger had to be made after 1839, and likely the later part of the 1840s at the earliest. Kwah died in the spring of 1840. The dagger is of the notched blade type, which also fits with a later date for the dagger.

With this evidence we must conclude that the dagger owned by chief Louie Billy was not Kwah’s dagger. It may have been a dagger owned by one or two of Kwah’s sons and then passed on to Louie Billy. It is likely that Kwah had several daggers in his lifetime and some of these may still be around in private or museum collections.

The specific dagger in the Royal B.C. Museum collection that once belonged to Chief Louis Billy has been shown to be a product of the post 1830, trade period. In spite of the results of the study of this particular dagger, it is clear that both direct and circumstantial evidence support the oral traditions of First Nations in the Northern Interior of British Columbia that claim the use of iron tools long before the European fur trade period.

The information presented here is often that of outsiders. The Nakazdli have other versions of the Kwah story – which I will leave for them to tell. The dagger of Louis Billy has an interesting story in itself, and has helped keep alive some of the oral traditions of the Nakazdli people – traditions that weave into the story of Kwah’s dagger. This research demonstrates how artifacts in museum collections may have bigger stories to tell than their current documentation reveals.

It is certainly reasonable to suggest that this story has not come to an end. That somewhere out there, lying in some museum or private collection, and waiting to be found, is the first iron dagger that once belonging to the Nakazdli noble, Kwah.

Note #1. Hudson’s Bay Company records indicate that at least one family was observed camping at the Chinlac village in 1829. Nak’azdli stories talk about a few people living there in the early 1900s.

Elements of the Chinlac story, and the subsequent revenge raid on the village about 1780, appear to be combined in some later telling of the stories (see story by Maxine George, Duff, 1951, and story by Sarah Prince (ed) Sam, 2001, pp. 20-23).

Morice was told about a nephew and son-in-law of Na’kwoel, named Tsaluk’ulyea, who inherited his noble title. Tsaluk’ulyea was born about 1735 and lived at the village of Pinche on Stuart Lake. His brother-in-law and first cousin was Nak’woel’s son A’ke’toes.

In the traditional Nak’azdli society it was the preferred practice for a man to marry his mother’s brother’s daughter, live in his uncles household and inherit his uncles land and title.

Appendix I

Oral and Written History of Incidents Involving Kwah’s Dagger and James Douglas.

In 1845, Alexander Simpson quoted a letter written by Douglas about the incident with Kwah, but fur trader John McLean wrote the first published story of the incident involving Kwah’s dagger in 1849 (McLean 1849). Father Morice indicates that McLean’s information was furnished “long after the event by Waccan, the interpreter”. This was Jean Batiste Boucher [described as a ‘half breed’] who was away at the time of the event. John Tod, who once was in charge of James Douglas when Douglas was at Fort McLeod, wrote about the incident in his memoirs (Tod, 1878; Sproat 1905; Wolfenden 1954)

Morice presents his version of the story which he claims “is a careful digest of all the accounts of the affair by disinterested native and surviving Hudson’s Bay Company parties, and, the writer has no doubt as to its perfect correctness” (1904:137-140).

Another sensationalized account was written by Matthew Macfie in 1865. Father Adrian Morice‘s versions of the Kwah’s dagger story were influenced by Macfie who is listed by Morice as one of the “Authorities Quoted or consulted” (Morice 1904:341-42). On pages 465 – 468, Macfie relates:

“An exciting passage in the experience of Sir James Douglas, …when he served in the capacity of chief trader [clerk] of the Hudson’s Bay Company at one of their posts near Stuart’s Lake. The circumstance was told me by a retired officer of the company, who lived nine years in the country now known as British Columbia.[This would be John Tod, who was stationed for nine years at Fort McLeod in the 1820s – see Belyk 1995] .Two employees of the company had been wantonly killed at a fort, two Indians having been concerned in the deed. One of the perpetrators was caught and shot soon after the crime had been committed. The other escaped detection for six years. There was an Indian encampment in the neighborhood of the fort, commanded by Mr. Douglas, whence came a native one-day, and assured him that the criminal who had been so long at large was secreted in the native lodge. Mr. Douglas with his men armed themselves and hastened to the spot. .All the apartments of the lodge were found vacated, with one exception. The chief of the tribe was giving a potlatch (feast) to friendly tribes who had come from a distance, and the inhabitants of the village had followed him to the place – some way off – where the festivities were being conducted. The only person Mr. Douglas found at home was a woman with a child in arms. After having examined the other divisions of the lodge, their suspicions prompted them to look once more in that room where the squaw was, and they found her still in the same posture. They ventured this time to pull her from the place where she stood. …down fell a bundle of clothes and mats, and out rushed the murderer; the Hudson’s Bay Company’s employees blazed him, but with the nimbleness of an eel he zig-zagged his way out of the house: their shots missed him, and he was about to escape when one of Mr. Douglas’s men leveled the butt end of his gun at him and felled him to the ground. .In the course of the day the chief and his retainers returned to the camp, and in consternation beheld the dead body of the man stretched on the threshold. The squaw informed her Tillicum’s of what had occurred. They instantly covered their faces with black paint, expressive of their belligerent intentions. The war-whoop was raised, and all the male inmates of the lodge, armed to the teeth, ran helter-skelter to the fort. The gates were open as usual. Mr. Douglas, reposing in the security afforded by the consciousness of having done his duty, and made no extraordinary preparation for repelling hostilities. The insensate mob, amidst threatening yells, forced their way into the apartment where the chief trader was, and, without allowing him time for parley, invested his commanding and portly person, threw him on his back, fastened his hands and feet, and bore him in struggling condition to the messroom of the fort, laying him on a long table, where I suppose, he expected to be put to death, with torture exquisite and protracted. Other servants were bound after the same fashion, but a few took refuge in the bastion, which they declared to the Indians was stored with powder. They also swore that if the Siwashes should venture to follow them, they would blow up the powder magazine about their ears. This menace had its desired effect. The old chief guarded Mr. Douglas. The former insisted on knowing the meaning of the strange and deadly assault that had been committed upon one of his guests. The dignified chief trader affected to treat the enquiry with scorn, and while rolling about on the table attempting to burst his bonds, threatened the venerable Tyhee with the most withering pains and penalties of the company. But the old savage, knowing that he had Mr. Douglas in his power, coolly replied that he was in no hurry, and would wait patiently till the chief trader should reason with him. When Mr. Douglas consented to listen to his statement, he sagely remarked: ‘I didn’t know that any murder had smuggled himself under my roof with the tribes who came to the potlatch. If I had known .I should have refused him shelter – I believe he ought to die. But you know that by the laws of hospitality existing among us Indians, any one who entrusts himself to our protection is sacred while under it, whoever he may be, and that we regard it a desecration to touch him while he is our guest’. Mr. Douglas proposed to atone for his proceeding by a present of blankets; and the word of a Hudson’s Bay Company’s servant with the Indians being ‘as good as his bond’, directly the promise was given the chief trader was set at liberty and an end put to pending troubles.”

Shortly after the first part of the above event, on August 3, 1828, James Douglas wrote to William Connolly at Fort Vancouver. Connolly, Douglas’s father-in-law, was in-charge of Fort St. James, but was absent during the incident. Douglas told him that “Zulth-nolly”, one of the persons who killed the Hudson’s Bay men at Fort George in 1823, had been caught and “dispatched on the 1st of this month in the Indian Village …without confusion or any accident happening to any other individual” (Rich 1944:311).

After William Connolly returned to Fort St. James, he wrote the following in the Fort journal on September 17:

“Some days after that affair [the death of Zulth-nolly] had taken place this old Rogue Qua, with as many members of his Tribe as he could muster, entered the Fort and made their way into the House all armed. Mr. Douglas suspecting that they had come with some evil intention immediately seized his arms, as also his men, but neither of them were able, from the crowd which surrounded them, to use them in turning these intruders out of the Fort. It is true that the Indians on their part used no other violence than to endeavour to preserve themselves from injury, and declared that they had no other view in this than to enter into an explanation with Mr. Douglas. But as that could have been done without such a display, the most favourable construction which can be put upon their conduct is that their intentions were by intimidation to extort what they might think proper in compensation for the death of their relation, and nothing but the determination of Mr. Douglas evinced of defending himself to the last, saved him from being pillaged, and perhaps from being killed” (Rich 1944:311-312).

The version told much later by Bancroft in his History of the Northwest, (1884(2):475) was also based on discussions one of his writers had with John Tod. Alexander Begg’s account (1894:135-37) is from reading John McLean and Bancroft.

Madge Wolfenden, of the Provincial Archives, wrote about the John Tod version of the story in her 1954 article: John Tod: ‘Career of a Scotch Boy’. She was influenced at this time by an article written by journalist/historian Bruce McKelvie in his 1949 book: Tales of Conflict. [An edited version of this was published in 1985, by Heritage House publishers that included a drawing of RBCM dagger #13345]. McKelvie produced another version entitled “Quaw Spares

Douglas” in his 1955 publication: Pageant of B.C. McKelvie first wrote about the dagger in a Newspaper Magazine story in 1938 entitled: Chief Quaw’s Historic Dagger. McKelvie’s knowledge of the dagger stories come from reading Morice and from his association with John Munro, the B.C. Deputy Minister of Agriculture, who was considered a friend of Kwah’s grandson, Chief Louis Billie. John Munro discussed Kwah and the dagger in his 1945 Doctoral thesis: Language, Legends and Lore of the Carrier Indians. Much of the information in the thesis paraphrased Morice but some was material obtained directly from Chief Louis Billy.

An article entitled: Chief Kwah’s Revenge, in the Beaver Magazine in 1943, by W. P. Johnson told by Chief Louis Billie and claimed to be “given practically as it was told”. In this earlier history of the Kwah’s dagger Johnson noted: “When I mentioned that some of Louis Billie’s story did not agree with Father Morice’s accounts, the old man was highly indignant and claimed that his were the authentic stories handed down by father to son and therefore bound to be correct.”

In two recent articles Frieda Esau Klippenstein (1994; 1996) discusses some of the earlier versions of the stories surrounding Kwah’s Dagger. She points out differences and biases in the earlier interpretations and some of the different versions of the story as told in recent times by Nak‘azdli band members, who are descendants of Kwah. She emphasizes how “The meaning of historical events and experiences is continually rewritten”, and the problems with labeling literary traditions as history and oral traditions as myths (1994). Arthur Ray has provided an overview of Kwah’s later life (Ray, 1978).

Appendix II

An Overview of the General Types of Daggers

Tlingit Type Daggers

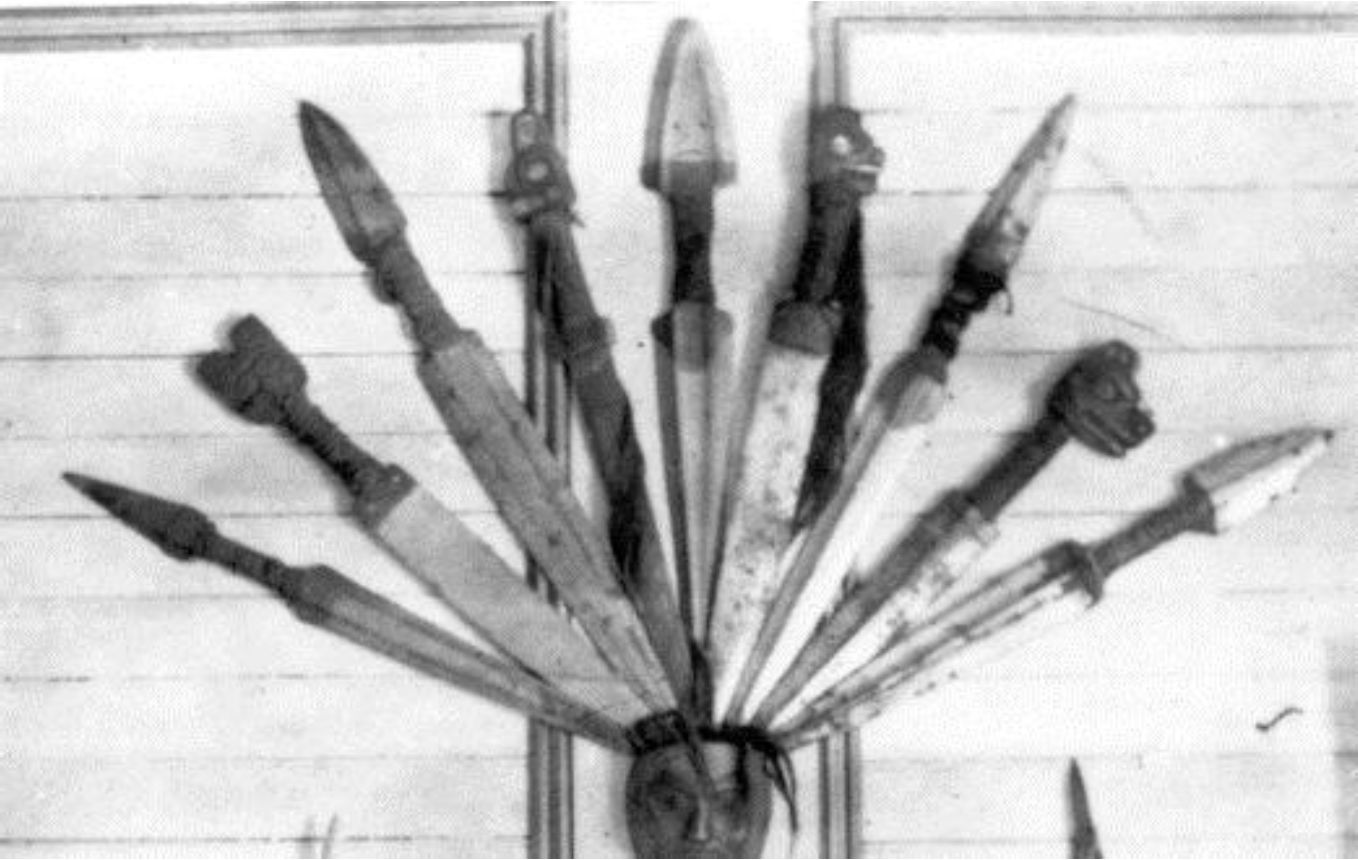

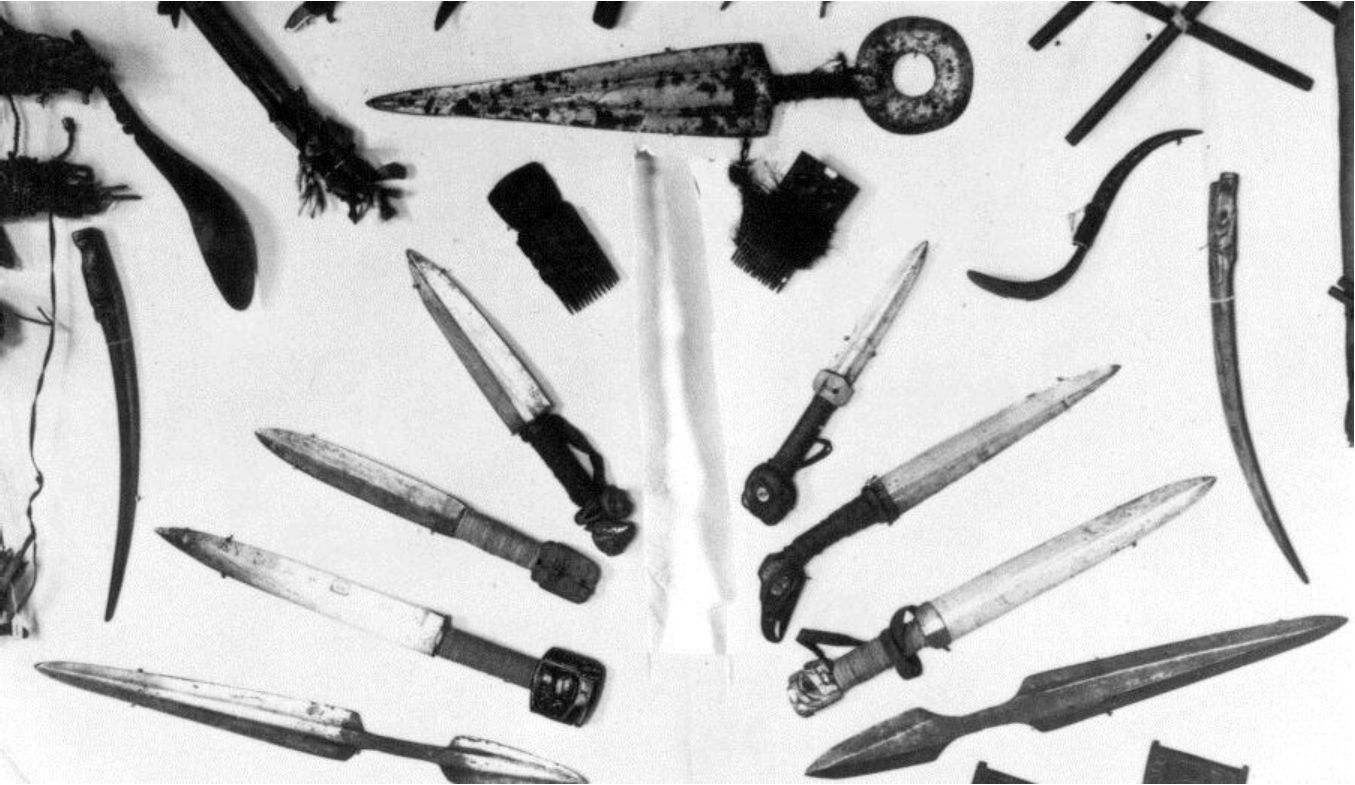

Figures 8A and 8B. Close-ups of two RBCM photographs show the dagger collection of ethnographer George Emmons in 1887. Two of the main dagger types discussed here can be seen. In photograph PN11877 the Tlingit type daggers include five of the nine shown here – two examples at each end. The others are of the type with wood or bone handles. In photograph PN9884, the Tlingit type daggers include the two at the bottom. Six daggers are of the type with wood or bone handles. The dagger at the top with the circular handle end is the one later drawn in Niblack (1890) and mentioned by Adrian Morice.

This type of dagger is often double bladed or having an iron/steel pommel shaped with an (often pointed) animal or human head. When double bladed, it has a short blade at one end and a much longer blade at the other end. One side is often concave with a fluting pattern across its surface and the other side is slightly concave.

Dixon collected one of these among the Tlingit in 1789(King 1981, Pl.38; Niblack 1890, Pl.28). Kyrill Khlebnikov made an observation among the Sitka Island Tlingit, probably in the later part of the time period that he was there (c.1817 to 1832). He said the Tlingit made a dagger “which resembled an English dirk and in beauty of craftsmanship was in no way inferior to the original. They make the common two-edged daggers from iron and decorate them with colorful shells” (Dmytryshyn, 1976:33). As mentioned, Wrangell had stated in the 1830s that the Eyak of Cooper River were the only metal workers who know how to forge iron at that time (Dmytryshyn et. al. 1989).

The Tlingit were clearly heating and hammering iron at this time. We cannot be certain from the information provided as to weather this forging activity was only done at moderately low temperatures – and with no knowledge of how to temper iron to produce a higher grade steel. Georg Erman (1841-1866 period), had the opinion that the native cooper was worked “without any smelting through mechanical means and that iron was used in the same way, patience replacing the technical knowledge” (Krause 1956:148).

By the 1830s it does appear that a small number of aboriginal people were using more advanced European iron working techniques. Tlingit metal smiths excelled at the making of highly refined steel daggers decorated with crest designs. These often have multiple tapering flutes down the center of the blade and overlay sheet copper at each end of the grip area. These were often made from steel files. John Dunn described these in the early 1840s as “beautifully fluted daggers … as highly finished as if they had been turned out of a first rate maker’s in London” (Dunn, 1844).

Alexander Mackenzie (Hudson’s Bay Co. agent), while on the Queen Charlotte Islands in 1884, obtained information on one of these daggers [Canadian Museum of Civilization – CMC VII-B-948]. The steel dagger was designed to represent a dogfish. The Haida told McKenzie that the knife was: “said to have been carved and tempered by a women who came from northern Alaska. Its history is known for two or three generations, it having passed from one chief to another, but its true origin is lost in obscurity” (Dawson, 1891). The information provided suggests this dagger dates back to at least, the 1850s. Similar daggers were being made in Alaska by this time.

Six of these Tlingit-style daggers, five made from ferrous metal (wrought iron or steel) and one of copper were part of a group of 14 daggers from the Northwest studied by Wayman, King and Craddock (1992). Their study included a re-examination of the two knives previously examined by Lang and Meeks (1981).

These previous studies of early iron from B.C. involved x-ray fluorescence analysis using a scanning electron microscope and x-radiography studies that can reveal information about the material and technologies used to produce the knives. The x-ray fluorescence analysis is limited because it can only accurately detect most elements at around 0.1%. X-radiography can define weather the basic material of the knife is made from an older or more modern technique and weather it has been re-forged by high temperature techniques not practiced in Northern North America by First Peoples prior to the early 19th century. It can also show that forging occurred at low temperatures and therefore – with other information – suggest which iron/steel knives could have been or were likely to have been modified or finished by First Nations smiths.

The Wayman, King, Craddock study concluded that “of the six daggers, at least five have been shown to have been made using the materials and technologies expected from the contact period which followed the onset of the maritime th (sea otter) fur trade in the last two decades of the 18t century. No speculation was possible with regard to the origin of the ferrous materials. …The forging of the blades to their final shapes seems to have been carried out at a surprisingly low temperature, consistent with this being the work of local smiths”.

Although the Tlingit type of dagger was around in the 1780s, the more artistic specimens seem to have been collected and donated to Museums around the world in the period between the late 1860s and 1890s. These daggers were likely made in small numbers in the 1840s period. Larger numbers and many of the more artistically designed specimens were likely made in the 1850s to 1880s period. Earlier, less artistic knives collected in the late 1700s – such as dagger # 1596 in the Spanish, Museo de America, collected as part of the Malaspina expeditions of 1776 to 1792 – may be proto-types for these later “Tlingit” daggers.

Y-Handled or Athapaskan Knives

An early form of dagger has a Y-shaped pommel or proximal end. The two extensions are cut off square. The blade is flat on one side and beveled on both edges on the other side. This type exists in drawings and collections from the 1780s to 1790s period and is found in archaeological sites in the Fraser River Basin. These latter specimens may be from the late 1700s or belong to an earlier pre-contact period. Some of these have a very large spiral and others a small spiral on the end of a straight or curving proximal end of the handle. One of these is illustrated by Dixon (1789) and referred to by Leroi-Gourhan (1946) as one of his “antenne” types (1946:298, fig. 489). Another (No.1596) in the Museo de America was collected during the Malaspina expeditions of 1776-1792 (Wayman, King and Craddock 1992:19-20). One specimen (de Laguna 1964, fig. 13) was found at an archaeological site in Yakutat Bay. According to de Laguna the site was used after the Russians were expelled in 1805 (de Laguna, 1964:126).

One of the best descriptions of the varieties of this type comes from the diary of Joseph Ingraham who drew sketches of the three types he observed on the Queen Charlotte Islands in September of 1791 (Ingraham 1791:2).

Later, more refined, versions of this general type are the ones referred to as athapaskan knives (see Rogers 1965). These later versions include the Y-shaped proximal end and a single extension of the Y that is tightly curved or spiraled.

These have been called athapaskan knives because they were common among Dene speakers of the Interior of Alaska and northern B.C. Many of these exist in Museum collections and many are represented on drawings on Dene people in the mid 1800s.

Museum specimens are often poorly documented. One of these, however (CMC VII-A-261) collected on the Chitena River, a branch of the Copper River in Alaska, was made by “Chief Escalada of the Chitena band”. Escalada noted that the proximal end was “split to represent the horn of the mountain sheep” (Rogers 1965:3,Pl.3G).

Many of this style are made of copper as well as Iron/steel. A specimen from the Canadian Museum of Civilization (CMC945; old #1331) is of “tempered copper, the mode of its manufacture being said to have been possessed by the ‘ancients’, who could hammer out native copper and give it a keen edge.” (Dawson 1891).

The Wayman, King, and Craddock study analyzed four specimens of this type. Two steel specimens (1944-Am-2- 178; 1944-Am-2-179) were possibly collected around 1828, when George Simpson visited what is now northern British Columbia. Two other specimens collected in 1888-9 (1890.98.77; 1890.9-8.78) from the Kutchin of Interior Alaska have their tang or proximal forged into a Y shape, but the tips of the Y have been cut and rolled around into tight spirals. It was concluded that the latter two “are likely to have been fabricated from files, probably by native smiths” (Wayman et. al. 1992).

Iron Bladed Daggers With Wood or Bone Handles

A common type of dagger or knife has a raised center or flute on one side of the blade and a hide-wrapped wooden or bone handle fastened to the tang or proximal end. Sometimes the blade is flat on both sides or is a piece of a European manufactured sword blade. The handle has zoomorphic features. The carved end in the form of a bear, raven or human head are common. These often have eyes, ears or teeth decorated with inlaid abalone shell. This diverse type seems to be mostly collected in the 1870s to 1890s and made mostly in the 1840s to 1860s period. Modern imitations of some of these were made in the 1960s-70s and are often sold on the market as older specimens.

Notched Knives

This knife is flat with a long straight tang and distinct side notches near the base of a beveled edged blade. This type was most typical of those mass produced by European and American manufacturers for the North American fur trade and based on a similar military “pike”. These have been found in 19th century archaeological contexts across North America. Many of these are stamped with manufacturer’s marks.

The RBCM dagger # 13345 once belonging to chief Louie Billy is one of these notched varieties and does not appear like the 18th century daggers made from a piece of wrought iron.

Ring Handled Daggers

One type of dagger usually dating to the last half of the 19th century have bone handles with an open metal circle at the proximal end of the handle. The bone part is often carved with a circle and dot motif. Some of these were made from the broken halves of steel bear traps. The trap part was composed of a folded piece of steel with a circular hole in each end that came together when. A frilled design was often carved around the proximal end. When not made from a bear trap part, a separate brass end was added in imitation of the latter type. This iron or brass proximal end of the handle was usually notched to give it an overall frill design.

Appendix III

Metalurgical Analysis

Metallographic examination. This method of surface analysis can be used to distinguish older and newer manufacturing methods and therefore identify metal produced after a general time-period. But often these time-periods are too general and vary from area to area.

In Europe, carburization of wrought iron, to produce harder steel was employed during the Iron Age. Since it was only possible to carburize a thin surface layer, the technique of forge-welding together a number of thin strips of carburized iron, to produce a piled or laminated structure, was also developed during the Iron Age (c. 1100 B.C.).

Carburization and the making of steel:

The microstructure of wrought iron, as seen in polished etched sections, consists of grains of iron, known as ferrite, crossed by fibrous inclusions of slag. Such iron is too soft for knives and needs to be hardened by heating in glowing charcoal at temperatures above 900 degrees C.

This process, known as carburization, converts the wrought iron into steel by allowing it to absorb carbon, the concentration of carbon in the iron-carbon alloy (i.e. steel) being in the range of 0.5 to 2%. The carbon combines chemically with some of the iron to form iron carbide, which results initially in a microstructure that is a mixture of ferrite and pearlite grains. With increasing concentrations of carbon (i.e. greater than 0.85 percent), the microstructure converts to a pealite and cementite mixture (Tite 1972).

Temporing:

The steel produced by carburization possesses an additional important property in that it can be hardened still further by heating to a temperature above 750 degrees C in a reducing atmosphere and then quenching rapidly in cold water. This process eliminates the pearlitic structure and in its place a new phase, martensite, which is a supersaturated solution of carbon in iron and has a needlelike structure, if formed. The quenched steel, although very hard, is distinctly brittle and liable to fracture.

However, the brittleness can be reduced, with some loss of hardness, by reheating to a lower temperature (around 450 degrees). This process, referred to as tempering, converts the martensite into a new phase, sorbite, which is a fine dispersion of cementite in ferrite.

Identification of the various phases in iron-carbon alloys (i.e. ferrite, cementite, pearlite, martensite, sorbite) is possible through the examination of polished etched sections under reflected light. Consequently the processes (i.e. carbonization, quenching, tempering) used in the manufacture of iron and steel artifacts can be ascertained (Tite 1972).

References

Bancroft, Herbert Howe. 1884. History of the Northwest Coast, 1800-1846, San Fransico: A.L. Bancroft.

Bishop, Charles. 1978. Kwah: A Carrier Chief. In: Old Trails and New Directions: Papers of the Third North American Fur Trade Conference, edited by Carol M. Judd and Arthur J. Ray, pp. 191-202, University of Toronto Press.

Borden, Charles. 1952. Results of Archaeological Investigations in Central British Columbia. In: Anthropology in British Columbia, (3):31-43, British Columbia Provincial Museum, Department of Education, Victoria, (ed) Wilson Duff.

Borden, Charles. 1952. An Archaeological Reconnaissance of Tweedsmuir Park, B.C. Museum 7, Art Notes, 2(2), April.

Campbell, Walter Neil. 1947. Kwah; a historic incident in which Sir James Douglas and Chief Kwah play the Leading Roles. In Cariboo and N.W. digest, 3(1)14, 86-87, 94-95.

Campbell, Walter Neil. “Kwah chief”. Manuscripts, magazines, newspapers. BCARS, MS-2280. (Campbell 1889-1964) File 1 – photo of grave board. “Snap taken by myself in 1933”.

Carl, Clifford. 1969. Letter to Clifford P. Wilson of January 9. Royal B.C. Museum Archives, GR0111, B45, F18.

Daily Colonist, Victoria. 1934. May 20. “Honor Done Memory of Famous Native”. Illustration of Kwah burial plaque. [“Here lie the remains of Great Chief Kwah. Born about 1755, died spring of 1840. He once had in his hands the life of future Sir James Douglas by was great enough to refrain from taking it”].

Dawson, George. 1891. Descriptive Notes on Certain Implements, Weapons, etc., from Graham Island, Queen Charlotte Islands, B.C. by Mr. Alexander Mackenzie. With an Introductory Note by Dr. G.M. Dawson. Proceedings and Transactions, Vol. IX, Section II, Royal Society of Canada.

De Laguna, Frederica, et al. 1964. Archaeology of the Yakutat Bay Area, Alaska. Smithsonian Institution. Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 192, Washington.

Dmytryshyn, Basil; E.A.P. Crownhart-Vaughan and Thomas Vaughan. 1989. The Russian American Colonies. To Siberia and Russian America. Three Centuries of Russian Eastward Expansion. 1798-1867. Volume Three. A Documentary Record, Oregon Historial Society Press.

Dmytryshyn, Basil and E.A.P. Crowhart-Vaughan. (translators) 1976. Colonial Russian America. Kyrill T. Khlebnikov’s Reports, 1817-1832. Oregon Historical Society, Portland.

Dunn, John. 1844. History of the Oregon Territory and British North American Fur Trade; with an Account of the Habits and Customs of the Principal Native Traits on the Northern Continent. Edwards and Hughes, London.

Hall, Lizette. 1992. The Carrier, My People, Friesen Printers, Cloverdale, B.C. Second printing with additions, Papyrus Printing Ltd, Prince George, B.C.

Heritage House. (Publishers) 1985. New Caledonia Conflict. In: Tales of Conflict. Indian-White Murders and Massacres in Pioneer British Columbia, pp. 36-43.

Ingraham, Joseph. 1791. “Manners and Customs of Indians, Washington Isles – from the Diary of Capt Ingraham on board the ship Hope – September 1791, Vol.3, p.128”, Smithsonian National Museum Archives, Ms # 1034.

Joint Reserve Commission. Minutes 1876-1907. (BCARS,GR- 2982.

Johnston, W.P. 1943. Chief Kwah’s Revenge, The Beaver. Sept, pp. 22-23.

Klippenstein, Frieda Esau. 1996. The Challenge of James Douglas and Carrier Chief Kwah. Reading Beyond Words: Contexts for Native History, edited by Jennifer S.H. Brown and Elizabeth Vibert, pp.124-151, Broadview Press, Peterborough, Ontario.

Klippenstein, Frieda Esau. 1994. Myth-Making At Fort St. James. The Search for Historical ‘truth’, The Beaver, August-September, pp. 22-29.

Krause, Aurel. 1956 (1885). The Tlingit Indians. Results of a Trip to the Northwest Coast of America and the Bering Straits, University of Washington Press, Seattle.

Lang, Janet and Nigel Meeks. 1981. Report of the Examination of Two Iron Knives from the North-West Coast of America. Appendix 5. In: Artificial Curiosities from the Northwest Coast of America. Native American Artefacts in the British Museum collected on the Third Voyage of Captain James Cook and acquired through Sir Joseph Banks, by JCH King, British Museum Publications Ltd.

Macfie, Matthew. 1865. Vancouver Island and British Columbia, Their History, Resources and Prospects, pp. 465468. Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, & Green, London.

McDougall, George. (1822). Fort Chilcotin, BCARS, Ms. C43. McKelvie, Bruce A. Chief Kwah’s Historic Dagger. Vancouver Province, Magazine Section, January 16, 1938.

McKelvie, Bruce A. Chief Kwah’s Historic Dagger. Vancouver Province, Magazine Section, January 15, page 3, 1938.

McKelvie, Bruce A. 1949. New Caledonia Conflict in Tales of Conflict, pp. 26-31. The Vancouver Daily Province, Vancouver.

McKelvie, Bruce A. 1955. Quaw Spares Douglas. In: Pageant of B.C. Glimpses into the Romantic Development of Canada’s Far Western Province, pp. 98-100, Thomas Nelson & Sons (Canada) Limited.

McLean, John. 1849. Notes of a Twenty-five Year’s Service in the Hudson’s Bay Territory, Vol. 2, Richard Bentley, London. [Reprinted, Champlain Society, Toronto, 1932, (Ed) W.S. Wallace].

Morice, Rev. Adrian G. 1894. Notes Archaeological, Industrial and Sociological, on the Western Denes, with an Ethnological Sketch of the Same. Transactions of the Canadian Institute, Session 1892-93, 4:1-222, The Copp, Clark Co. Ltd., Toronto.

Morice, Rev. Adrian G. 1904. The History of the Northern Interior of British Columbia. Formerly New Caledonia. [1660 to 1880]. William Briggs, second edition.

Morice, Rev. Adrian G. 1906. The Great Dene Race. Administration of “Anthrops”, St. Gabrie-Modling, Near Vienna, Austria, The Press of the Mechitharistes.

Munro, John Bunyan. 1945. Language, Legends and Lore of the Carrier Indians. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Ottawa.

Niblack, Albert. 1890. The Coast Indians of Southern Alaska and Northern British Columbia. Based on the Collections in the U.S. National Museum, and on the Personal Observation of the Writer in Connection with the Survey of Alaska in the Seasons of 1885, 1886 and 1887.

Ray, J. Arthur. 1974. Indians in the Fur Trade, Their Role as hunters, trappers and middlemen in the lands southwest of Hudson’s Bay, 1660-1870, Univ. Toronto Press.

Sam, Lillian (ed) 2001. “The Revenge of Ts’ohdai’” compiled by Ann Sam. In: Nak’azdli t’enne Yahulduk. Nak’azdli Elders Speak, Theytus Books Ltd., Penticton, B.C.

Rich, E.E. (ed). 1944. The Letters of John McLoughlin. From Fort Vancouver to the Governor and Committee. Third Series, 1844-46. The Champlain Society for The Hudson’s Bay Record Society.

Rogers, Edward S. An Athapaskan Type of Knife. Anthropological Papers, Number 9, National Museum of Canada.

Sam, Lillian. (Editor). 2001. Nak’azdli t’enne Yahulduk. Nak’azdli Elders Speak, Theytus Books Ltd, Penticton, British Columbia.

Simpson, Alexander. 1845. The Life and Times of Thomas Simpson, London.

Stwertka, Albert. 1998. A Guide to the Elements. Revised Edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Tite, M.S. 1972. Methods of Physical Examination in Archaeology. Seminar Press, London and New York, pp 389.

Tod, John. History of New Caledonia and the Northwest Coast, 1878. Photocopy in British Columbia Archives and Record Services (E/A/T56). Original manuscript in Bancroft Library, Pacific Coast Mss, Series C, No.27, University of California, Berkeley.

Watson, Robert. 1928. Fort St. James, Sir George Simpson Centennial. The Beaver, Dec., 8:101-103, BCARS, NW905B386.

Watson, Robert. 1931. James Douglas and Fort Victoria. The Beaver, Sept., 9(5):271, BCARS, NW905B386.

Watson, Robert. 1934. Kwah’s Dagger. The Daily Colonist, Nov. 4. Magazine Section.

Wolfenden, Madge. 1954. John Tod:’Career of a Scotch Boy’. British Columbia Historical Quarterly, Vol. XVII, July-October, Nos. 3 and 4, pp. 133-(238?).