Introduction

Fishing was a major part of the traditional Lekwungen economy. The availability of some fish resources, however, changed on a decadal basis because of the changing water temperatures (Chevez et. al. 2003) and the intensity of important seasonal fish runs could vary over longer periods of time due to other climatic factors (Finney et. al. 2000 and 2002). There were times when the salmon runs did not arrive or drought conditions prevented them from running up local streams. People then had to refocus on other resources or starve.

Although a few species of fish were often considered the most important, the old village sites reveal the remains of numerous species. Not enough analysis of fish remains from sites has yet been undertaken to get the full details of what fish were eaten and in what proportions. Modern DNA studies are beginning to change this (see McKechnie et. al. 2014; Rodreges et. al. 2018). The bones of smaller fish, especially, were not collected in the past because of screen mesh sizes being too large. Some of the smaller fish species that were around Victoria in the 19th century were eliminated or drastically reduced by commercial overfishing.

The Lekwungen fishers based their activities on their knowledge of the currents, tides, depths of waters and knowing when bait fish were around. It was the type of bait that attracted the salmon and determined the kind of bait that Indigenous people would use in jigging or trolling for larger fish. When birds were observed eating the large balls of needle fish on the greater Victoria water front, Indigenous people would know that the Chinook salmon would be there or coming shortly. In March the herring fish are coming in to spawn from the west coast of the Island, attracting the larger predator fish

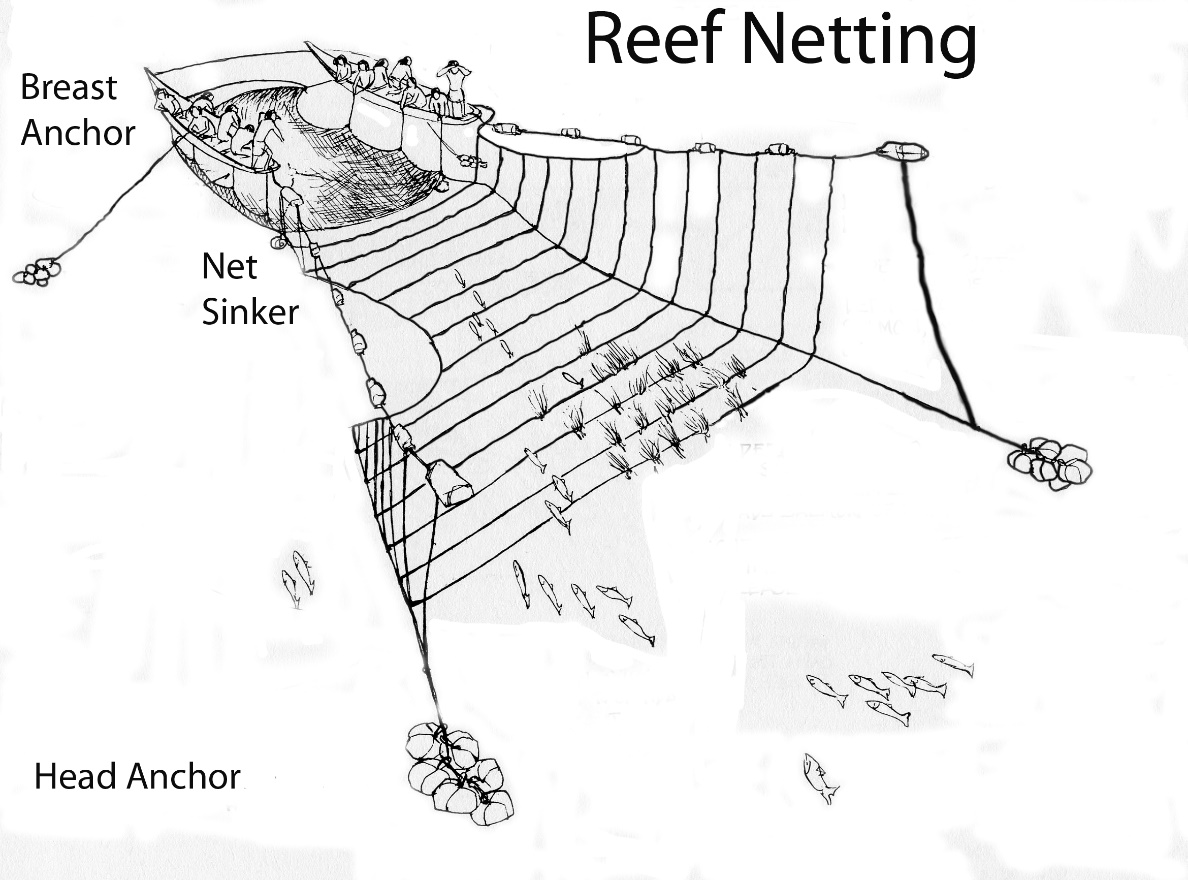

The Lekwungen had more permanent village sites used primarily in the winter time. If the fishing was not nearby, they would travel to small seasonal sites closer to the fishing areas. Some of these tended to be in the more exposed locations along the waterfront. Very few specific traditional locations were provided by Indigenous consultants in the late 19th and early 20th century with the exception of Reef netting locations.

Here I will present a brief overview of the changing landscape, the historic 19th century observations of Indigenous fishing by the Lekwungen and outsiders and blend this with information we know about in regard to modern “sports” fishing. Three Appendix will expand upon Indigenous knowledge by providing an overview of the first Salmon ceremony, a story of the Origin of Salmon and the use of the Swala or Reef net from the ethnographic literature. It is very likely that most of the modern “sports” fishing areas would also be those that were the focus of the Lekwungen peoples in their history.

What is not included here is detail on the San Jaun Island fisheries that were once important to the Lekwungen before they were cut off with the creation of the boundary line of the United States. Anthropologist Wayne Suttles recorded information, mostly from Songhees, Tom James of Discovery Island, regarding 14 reef net locations on San Juan Island and one on Henry Island. Tom James believed that the original home of the Songhees was at the north end of San Juan Island. Louis Pelkie of Saanich believed that the latter location “originally belonged to the Teleqamis tribe” of San Juan Island (see Suttles 1974; 1998).

Resource Changes of long time periods

All of the area identified as Lekwungen territory today went through drastic changes over time in its size due to sea level change, climate change, types of resources available and the location of resources over time.

Gradual climatic warming occurred after the Last Glacial Maximum started receding around 20,000 years ago. This warming period increased during a warmer and dryer climatic period called the Bølling-Allerød dating from 14.69 to 12.89 thousand years ago. This period was followed by an ecological shift called the Younger Dryas, from12,900 to 11,700 years ago, that saw a return to colder glacial conditions.

The long glacial period called the Pleistocene came to an end with the Holocene warm period beginning 11,700 years ago. Over the next 800 years bison roamed the Victoria region with herds of elk. We currently have no knowledge of what kind of fish frequented the Victoria area at this time, but it would have included some species of salmon that we know travelled up the Fraser River by this time.

14,000 years ago, todays Lekwungen territory was mostly under water (Keddie 2019). As the land rebounded from the sea, more and more land became exposed. It reached near its present level for a brief period around 11,000 years ago but continued to lower. By 8,000 years ago Victoria Harbour, Esquimalt Harbour and the existing bays were dry land. The sea had retreated to locations that are now under, at least, 25 meters of water and possibly as much as 45 meters. As the land settled down the sea slowly rose to near its current location by around 4200 years ago. I dated two Archaeological sites to this time period, one at Fleming beach in Esquimalt and another at the narrow Gorge falls area up the Gorge Waterway. During this time not all of the existing fish resources may have been available and the specific location of various resources would have changed.

A major drought occurred in the region 2800 years ago and at various times after that. 2300 years ago, the Victoria region saw a climatic transition from a relatively warm and moist mesothermic mid Holocene to the cool and wet Holocene (Hebda 1997 and 2022). Major cultural changes may have occurred at this time due to the impact on the landscape and its resources. The growth of Cedar forests was an important resource brought about by a wetter climate.

In addition to the changing landscape, the linkage between Ocean-atmosphere circulation and northern Pacific ecosystems saw major changes in the quantity of fish resources. Major changes in fish populations occurred to the north in Alaska between 2100 hundred and 800 years ago. Much of this was due to water temperature and the upwelling of fish food resources. We do not yet have the details of how these changes affected the Victoria region.

In Alaskan waters there was a greater abundance of Sardines and Anchovies from around 1700 to 800 years ago and an increase of salmon from 1200 to 800 years ago followed by less abundance of Sardines and Anchovies (Finney et. Al. 2002). We know from deep sea coring studies in Saanich Inlet that herring fish were present for 10,000 years, but anchovies only appeared in the inlet after 2000 years ago. Anchovy populations increase during periods of cooler water temperatures and fish like sardines are more common along the coast during periods of warmer waters. We cannot assume that Lekwungen food supplies were always dependable and plentiful.

Historic Documentation of Fish Resources

The Changing Economy

The Indigenous economy was undergoing change throughout the 19th century due to de-population and changes in family movements, marriage patterns, access to resources, and as individuals worked for wages to purchase goods. Indigenous peoples adopted European fishing gear in the 19th century and undertook different fishing practices to supply the non-Indigenous market. This resulted in the loss of knowledge of some of the older methods of fishing.

Before contact with Europeans food resources were likely to have fluctuated over time. Different family groups may have focused more attention on, or only had rights to, certain limited resources. In almost every regional population there were families with a stronger focus on land resources, as opposed to the majority who focused on marine resources.

The Treaty territories of the Lekwungen family groups presented in 1850, were not equal in their resources. The use of common resources and the shifting of individuals between groups may have only modified this imbalance in part. In the late 19th century fish continued as an important food source but the specific ownership rights, social obligations and associated ritual were being eroded away.

The new foreigners had no understanding of the linkage between the local rights, religion and resources. The goals of the European and American religions served to actively erode the system of balance engendered by traditional Lekwungen practices (see appendix 1 and 2).

The Lekwungen increasingly began gathering resources for others. James Bell described the situation in 1858:

“We are indebted to the Indians for a supply of everything in season … at very reasonable rates; They collect great quantities of Berries, …For a back load of Potatoes they charge one shilling …A fine salmon can also be purchased for one shilling; …Cod, Herrings, Flounders &c are always to be had cheap”.

THE FOOD RESOURCES

Oral history and the written record tend to focus on fish that migrate seasonally in large numbers. Modern identification of fish bones from old village sites shows that numerous species of fish were eaten, including many varieties of seaperch, sole, rockfish, sculpin, greenling and ratfish. This great variety likely proved crucial to the long-term survival of local populations when the larger seasonal species did not arrive when expected. Geologist George Dawson observed on April 6, 1876, that Midshipman are found in the Gorge waterway “between the Gorge and Craigflower” (Tillicum road and Admirals road] (Cole and Lockner 1989).

In 1848, James Wood notes that the most common fish taken in the general area of the Strait of Jaun de Fuca were “halibut, flounders, skate, rock cod, sardine, salmon, trout, and several varieties of the herring” (Wood 1848). The latter would likely refer to the Pacific Sardine and the Surf smelt that look like herring.

Flat Fish

Halibut were once very plentiful on the shallow offshore banks from Victoria harbour to Discovery Island. This traditional Lekwungen fishery was mostly practiced in the late spring and early summer fishing with a hook and line. Unidentified Lekwungen noted that the area southwest of Discovery Island, that today we call Oak Bay Flats, was a traditional Halibut fishing location (Suttles 1974).

In 1862, Forbes said herring, flounders, smelt and perch were seen as “important” fish. We know in historic times that Sole and Flounder (figures 4-6) were plentiful in the Royal Roads area off Esquimalt Lagoon where the Lekwungen “would expose flounders on spits to the sun in order to roast them.” (Boas 1916).

Today, March to May is the prime time for halibut fishing. The best fishing areas on underwater pinnacles and banks are Oak Bay Flats, Border Bank, Constance Bank, Albert Head and William Head (Figure 8). In June and July there are still plenty to catch. The best places to catch them in July is the West End of Constance Bank in 180′ of water, the Mud Hole in 300′ of water and Border Bank anywhere from 90′ to 250’. In August, Albert Head, William Head, and Constance Bank will continue to produce halibut. In September and October, they can still be found in deep waters off Race Rocks. Other places for Halibut include Zero Rock and Little Zero Rock off Cordova Bay.

Flat fish, in the family Pleuronectidae, found in archaeological sites around Victoria include: Pacific Halibut (Hippoglossus stenolepis); Rock Sole (Lipidopsette bilineata); English Sole (Parophrys vetulus); Petral Sole (Eopsetta Jordani); Starry flounder (Piatichthys stellatus); Arrowtooth Flounder (Atheresthes stomias). There are likely more flat fish species that could not be identified.

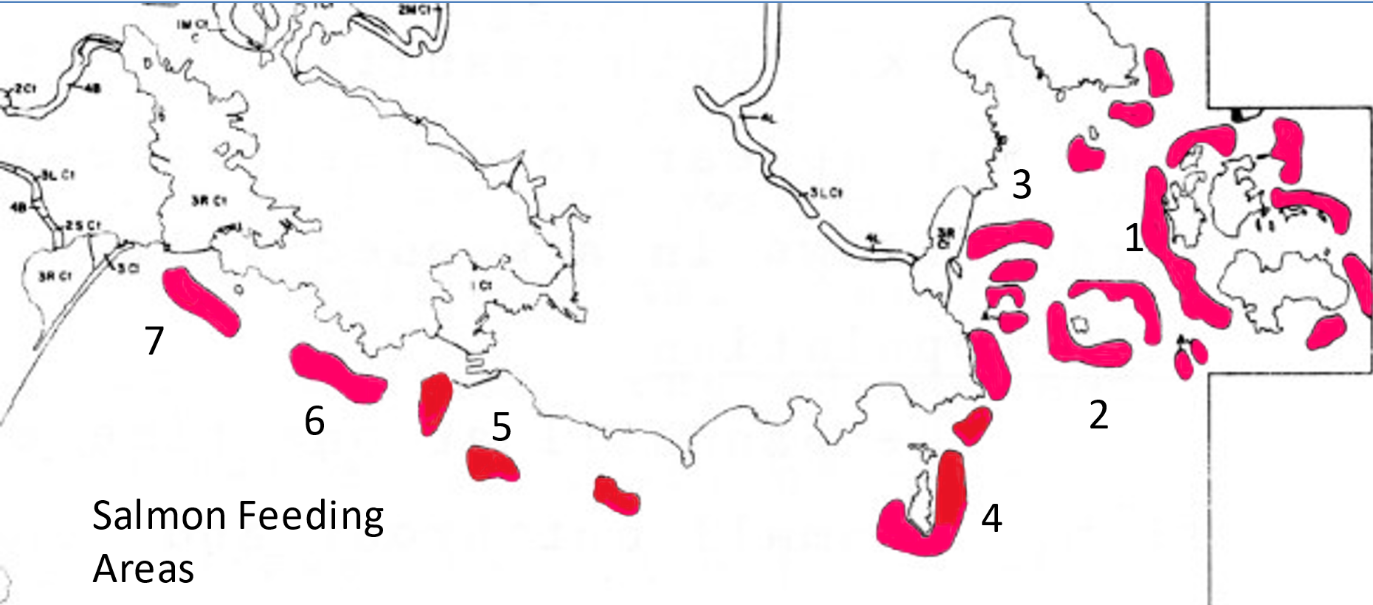

1. The Gap. 2. The Flats. 3. Cattle Point. 4. Trial Island. 5. Victoria Waterfront. 6. Macauley Point. 7. Royal Roads.

HERRING, SARDINES, ANCHOVY and SURF SMELT

The Pacific herring, noted James Douglas in 1843, arrive in April and are “taken in great abundance” in Victoria harbour. Frederick Dally describes this two-month Indigenous fishery in Esquimalt Harbour in 1865; when temporary shelters sprang up “along the edges of the bays and harbours”. When dried the herring were packed in 50-pound bales made of rush mats tightly lashed with bark ropes. Horses were used to carry the loads back to the “winter quarters”. Some of the fish were used “as lamps for lighting their lodges”. The six-to-eight-foot herring rakes had barbs “usually” of bone but “preferably” of nails. Figure10 shows the distal end of a full-size model of a herring rake made by the late John Smyly of the Royal B.C. Museum. Figure 11 shows herring rakes leaning next to a temporary mat lodge made of tuli reeds (see Keddie 2016).

Edward Bogg describes this Lekwungen fishing technique in 1867, with the “Herrings and Whiting [Pacific Hake (Merluccius productus)]”. A pole (14′ X 3″ X 3/4″) has one edge with “very sharp spikes, made of hard wood, and about two inches long”. The fisherman paddles quickly into a shoal of fish “drops his paddle, picks up his rake”, and “makes a sweep through the shoal” impaling 5 or 6 fish which are dropped into the canoe “by striking the rake forcibly on the gunwale”.

Bayley, in 1878, notes the “immense amount” of herring spawn or eggs preserved for winter use. The spawn is deposited on Cedar boughs placed “at low water”, then gathered and taken to camp and “stripped after being dried and put into boxes”. Paul Kane, in 1847, describes their preparation for immediate use. After the branches are “sunk to the bottom of the river in shallow places” with “heavy stones”. The branches “are all covered by the next morning with the spawn, which is washed off into their waterproof baskets by the hand into small balls and dried, and is very palatable.”

Geologist George Dawson in 1876: “Saw this evening in passing through the Indian village a large quantity of Herring spawn in process of drying. The Cedar and Spruce branches on which it has been deposited are hung up on poles like the herrings themselves” (see Figure 41). On August 28, 1876, Dawson: ”Saw a women today going about the streets today with a basket of fresh herring spawn for sale. It was attached thickly like small shot (but transparent and colourless) to filaments of sea weed” (Cole and Lockner 1989).

Captain Wilson observed in 1858-1859 that during October, and November, “herrings and a species of anchovy appear in great numbers”. Rev. Owens, after mentioning on September 30, 1869, that the Reserve had been nearly deserted over the past three months, due to the Songhees being away fishing, noted: “The abundance of salmon & anchovies has been extraordinary & unless actually seen would appear incredible”.

The B.C. Guide for 1877-78 says that during the autumn the anchovy “abounds in the harbours and inlets” and is easily taken. Anchovy bones have been found in large numbers in archaeological sites in the inner harbour and Gorge waterway. As noted earlier, Anchovy may have only been in this area for the last two thousand years.

Pacific Sardine or Pilchard (Sardinops sagax)

The larger Pacific Sardine (Figure 13) once came to the south end of Vancouver Island in large numbers but was devasted by historic overfishing.

Surf Smelt (Osmerus mordax) (Figure 14) were once common but heavily reduced by historic commercial fishing.

Pacific Hake or Whiting (Figure 15) is a true cod. It is currently the most abundant groundfish population. Edward Bogg describes how they were caught with a Herring rake in 1867. After spawning further north in deep waters from March to May, many adults aggregate on the Vancouver side of the Strait of Georgia where they form dense schools.

SALMON AND TROUT

James Douglas noted in 1843, that the salmon “ascends the straits in August, and are caught in great quantities” and “continue to yield well until September”. The “bad salmon until November” and “excellent Salmon” by trolling until the middle of February. The Spring salmon entered Victoria harbour all winter and Coho and Chum salmon ran up the gorge waterway in greatest numbers in June, when the Pink and Sockeye were available in the outer waters.

The Lekwungen resources included seven species in the family Oncorhynchus or salmonids as they were called collectively. These included Chinook, Coho, Chum and Sockeye salmon as well as Cutthroat and Steelhead trout. Sockeye and Pinks were mostly caught at seasonal reef netting stations on San Juan Island.

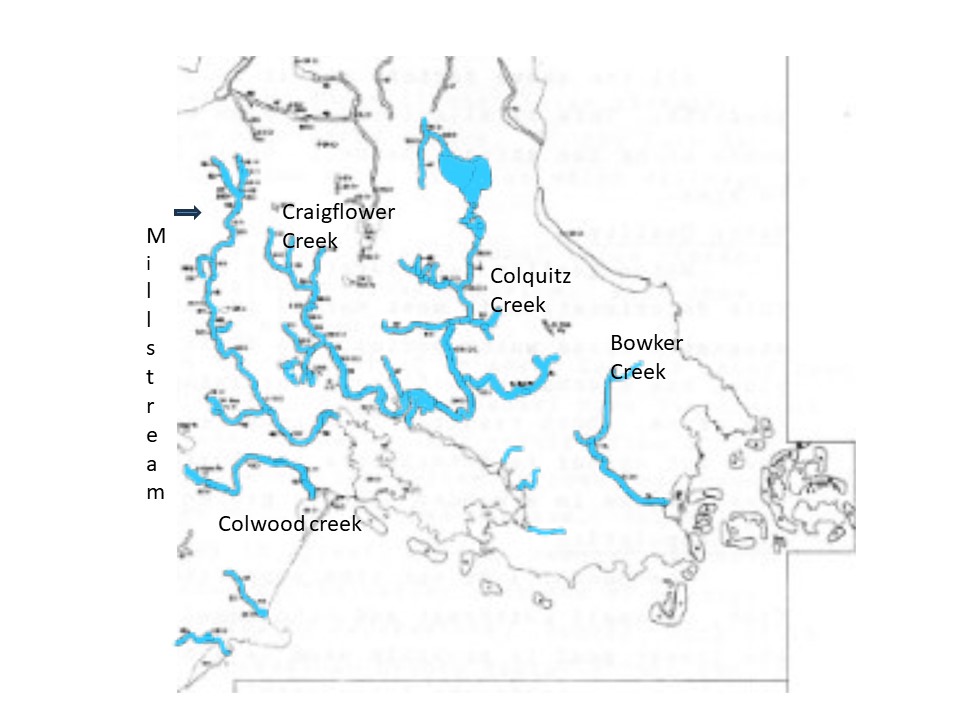

Chinook and Coho Salmon once ran up most of the local small creeks. In the early 1970s, I talked to a number of older people who grew up on these creeks. I learned that, as late as the 1920s, Coho went up Bowker creek past Haultain Street and trout as far as the tributaries past Hillside and Shellbourne Streets. Coho and Chum salmon ran up Colquitz creek, which emptied into Portage Inlet, and its tributaries to the north of West Saanich Road. Lekwungen individuals identified this as a traditional fishing location for Chinook and Coho (Suttles 1974).

Further up the Craigflower Creek basin, on May 27, 1987, I observed trout in the unnamed creek that ran north of Pike Lake as far as Blue Valley Road. Rainbow trout were regularly fished in the lower waters of this creek unto the 1950s. Steelhead trout are migratory and went up the streams in late fall at the same times as the Chum Salmon.

The three creeks that flow into Esquimalt Lagoon, Selleck, Bee and Colwood Creeks would have likely had salmon runs in the past based on their gradients. Millsteam has reintroduced Coho and would have had Steelhead in the past.

In 1862, Forbes said trout “some of them 4-6 lbs” are found “in all the streams and lakes”. In 1878, Bayley said there were no fish in Langford Lake but “others in the neighbourhood are full of fine speckled fish [rainbow and steelhead trout]”. Bass and other fish have been introduced into Langford Lake in historic times.

Fish were caught by a using a variety of equipment. Trolling and jigging with a single fish hook attached to a long kelp line was practiced in both deep and shallow waters off shore (see Keddie 2005). Wooden weirs of woven branches tied to posts were built across small streams to catch salmon and trout. The fish were either speared from the weirs or caught in wooden traps attached to them. In 1843, James Douglas reports the winter use of the basket trap on the Gorge waterway for catching trout. Likely places for these would be at the Gorge falls near the Tillicum bridge, other narrow areas on the Gorge, and at the mouths of streams exiting into Portage Inlet, such as Colquitz and Craigflower creeks and the mouth of Millstream creek in Esquimalt Harbour.

On December 23, 1858, the Victoria Gazette reports: “The Indians, many of whom have collected at this place, …have left this region, the locality of their summer homes, and gone across to the Gulf where they can procure fish and other marine products.”

Edward Bogg wrote an overview of the old Reserve and Songhees fishing practices as he observed them shortly before 1867:

“This village …is composed of long, low shed-like buildings, with the front higher than the back, … The uprights of these huts are posts, …These posts are never taken away; but the rough-hewn planks, which form the sides and roof of the dwelling, and which are fastened to the posts by ropes of seaweed, are always carried about, by the owners, in their migrations. When fishing season comes on, then the Indian takes down the planks, places them in his canoe, puts in, his baskets full of birch bark [wild cherry?], his collection of dried salmon-roe, and some bladders of fish-oil, and departs to the fishing grounds. Adjacent to these fishing grounds is the site of the summer village of the tribe, which, for six months out of the year, is only indicated by the posts I have already alluded to. But when spring comes, with it come the fish, the salmon, the rock-cod, the skate, and the shoals of Herring and Whiting [Hake]. Then the Indians come to the village, unload their canoes, tie their planks together, fasten them to the posts, put up bunks round the sides to form their sleeping places, clear away the enormous nettle-beds, which are the constant accompaniment and sure sign of an Indian encampment”.

In 1861, Forbes also notes how: “Hemp nettle grows wild around Indian lodges, and is used … to make a capital twine, which is manufactured into nets.”

Bogg notes the “ingenuity” that is shown “in the numerous contrivances and the untiring skill” of the Lekwungen:

“When the salmon comes in season, the men go out trolling in a very fast canoe, …They tow a long line astern made of seaweed, very tough and strong, and to this is attached, by slips of deer-hide, an oval piece of granite, perfectly smooth, and the size and shape of a goose-egg. This acts as a sinker, and it spins the bait. The salmon-hook is a piece of strong whalebone, at one end of which is a loop, and at the other, a piece of very hard wood, which is pointed, and lashed on to the whalebone at an acute angle. These hooks are very strong, and will hold the largest salmon. The bait is very often a red berry… but at other times it is a bit of dried salmon-roe.”

Salmon Fishing in 1863

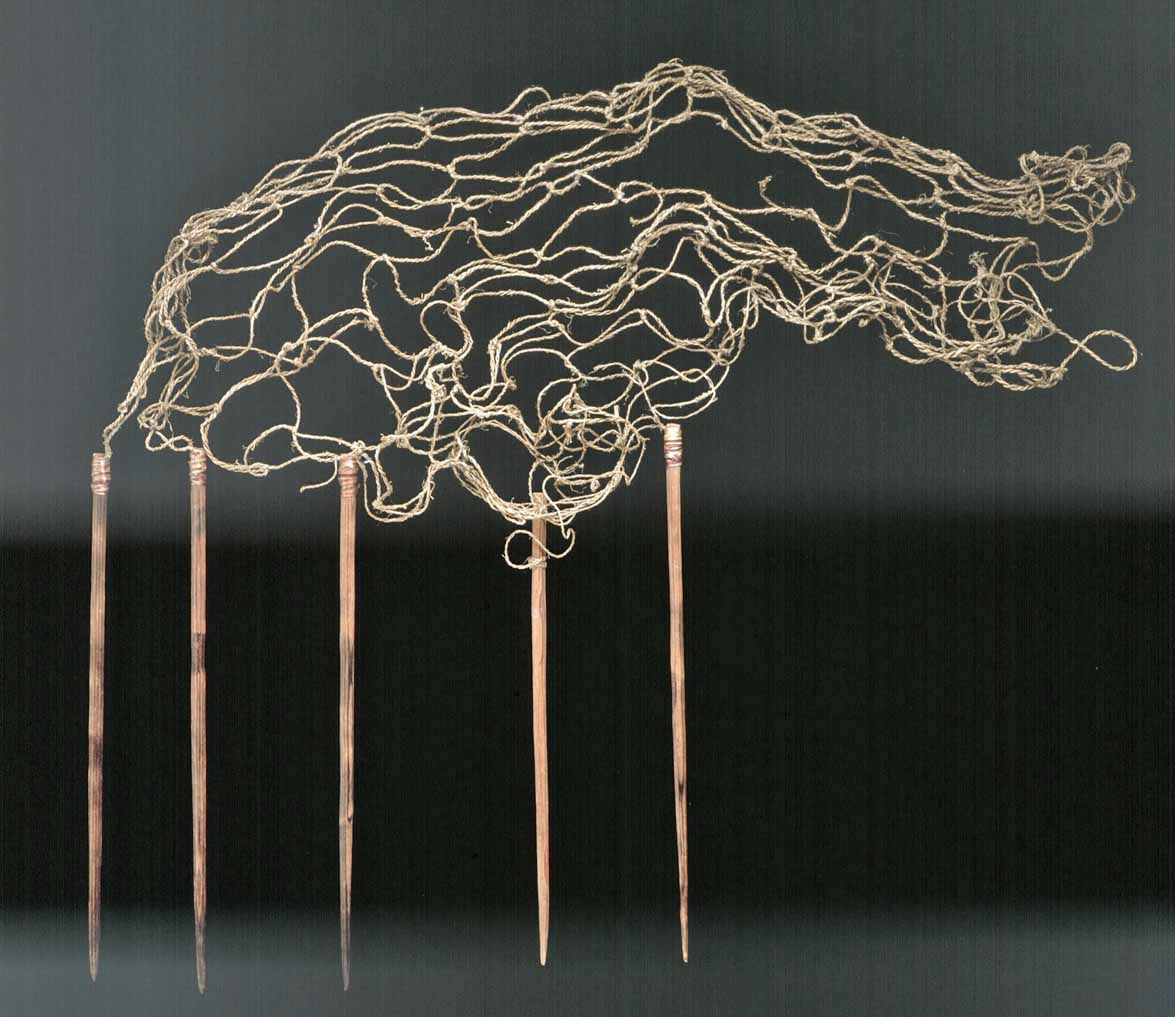

The naturalist John Lord described the use of a salmon gill net in Victoria in 1863:

“The Indians have rather a clever contrivance for catching them in the spring and autumn months in the bays and harbours. They use a sort of gill-net (a net of about 40 feet long and 8 feet wide), with very wide meshes; the upper edge is buoyed up by bits of dry cedar wood as floats, and kept stretched tight by small pebbles [at] four-foot distances along the lower margin as sinkers”.

This net was stretched across the mouth of a small bay or inlet while the person fishing sat in their canoe watching. As the shoals of anchovies and herrings escaped through the nets to the inner bays the pursuing salmon caught their heads in the net causing the floats to bob. The fisherman pulls up part of the net, clubs the salmon and drops it into the canoe, and waits for the next fish.

“With this kind of net immense numbers of spring and fall salmon are taken. All their nets are made from cord made from a native hemp … This the Indians pick about a week before the flowering time, soak it, and then beat into fibre. This fibre is picked carefully over and arranged in regular lengths [by the women] and then made into little bundles. The Indians … using only his naked thigh and hand, twists these little bundles of fibre into cord, and he lays it up …symmetrically as a ropemaker could with his revolving spindles”.

By the late 19th century, the Lekwungen were using European style fishing equipment and increasingly focused on the commercial aspects of the fishing industry. The late Chief John Albany (1916-96) told me that as a young boy in the 1920s, he went fishing with his uncles exclusively off Albert Head with gas powered boats. Individual Lekwungen people have, on occasion, continued to fish for trout and herring in the Gorge Waterway until recent times.

Dog fish and Skate

Two fish of the Sqaulidae family (Figure 21 and 22) found in archaeological sites include Spiny Dogfish (Squalus acabthias) and the big skate (Raja binoculata). Dogfish were easy to catch in later summer and fall. There are a lot of skate around the Victoria area in March and April. The skate are found near sandbars and shallow areas around river mouths. These fish could be speared when they were in shallow water or trolled fir in deeper waters. A commercial fishery for Dog fish began in 1870.

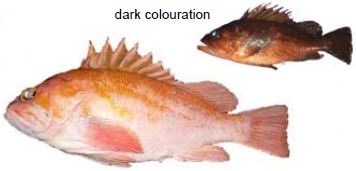

Rockfish Sebastes

Rockfish are a common fish in nearshore and deeper waters (Figures 23-29). A number of species of rockfish are found in this region but their bones are sometimes difficult to identify as to species in the archaeological sites. Those in the Sebastidae family that have been identified include the Redbanded rockfish (Sebastes babcocki); Shortraker rockfish (Sebastes borealis) and Redstriped rockfish (Sebastes proriger). Some in this family are mistakenly referred to as cod, but are not true cod.

Hexagrammidae

The family Hexagrammidae, found in local Archaeological sites include: Lingcod (Ophiodon elongatus), which is not a true cod. It is a non-migratory fish which can grow up to five feet; Rock Greenling (Hexagraminas supersiliosus) and Kelp Greenling (Hexagrammos decagrammus). The larger species would be harpooned in shallower waters at low tide.

Gadidae Family

The Gadidae Family includes the true Pacific cod (Gadus macrocephalus).

Cottidei

The sub-order Cottidei found in Archaeological sites include: Red Irish Lord (Hemilepidotus Hemilepidotus); Cabezon (Scorpaenichthys marmoratus); Great Sculpin (Myoxocepalus polyacanthocephalus); Pacific Staghorn Sculpin (Leptocottus armatus) and the Buffalo Sculpin (Enophrys bison).

Accipenseridae family

Of the Accipenseridae family, only the Green Sturgeon (Acipenser medirostris) is found in the Greater Victoria region in historic times. They are fairly rare in recent times but occasionally wash up on Victoria beaches. Sturgeon are mostly a cartilaginous fish and have only a few hard bones. This makes it difficult to find and identify as to species in archaeological sites. It is likely, however, that these fish, which could grow to a very large size were harpooned by Lekwungen when available.

Ratfish

A common fish resource of the Lekwungen, found in archaeological sites, is the Rat fish (Hydrolagus colliel) of the Chimaeridae Family.

Embiotocidae. Surf Perches

Family Pholidae

Of the Family Pholidae, the saddleback gunnel or saddled blenny (Pholis ornata) would have been available to the Lekwungen. They have not been identified in Archaeological sites, but given they can grow up to a foot long and are easy to collect by hand during spanning times, as I have done, it is most likely that they would have been a minor resource of the Lekwungen.

Figure 41. Fish Drying Stagings on the Esquimalt Reserve c. 1870.

Appendix 1.

BRINGING THE SALMON AND THE FIRST SALMON CEREMONY

On August 9, 1859, the Gazette newspaper of Victoria describes a Lekwungen ritual undertaken when the salmon did not appear at their usual time. The spirits were appealed to by placing a young girl in a “cage of wicker work” and “with fasting and prayers” she “tries to cajole the delectable fish” with the assistance of two old women. Note is made of the “devotional manner in which the Indians cross themselves after making a haul, but only when the salmon caught prove of extraordinary size is this done.” This making the sign of the cross was a practice adapted from the Catholic church for use in the continuance of some of their tradition prayer rituals.

In the 1930s, elders said the First Salmon rites were celebrated locally only for the sockeye and pink salmon. It was believed that these salmon were human beings from some far-away land that transformed themselves into fish during the migration season. At this season they never referred to any species by its common name, but called it selewa which means “rich man” or ceas meaning “elder brother”. The Songhees honoured the dead bodies of the fish by cutting them up on ferns which were then thrown into the water. When drying the fish in their houses or special smoking places they burned the seeds of the consumption plant (Lomatium nudicaule). The smoke of this plant was considered to be the food to the salmon people.

The Songhees celebrated over the sockeye, which they netted at their reef net locations off San Juan Island:

“They considered their net to represent a human being with head, body, arms and legs, …unless it was set in a certain definite way the leading sockeye would turn back disapprovingly and warn those behind. Since only a few priests knew how to set it, one always superintended the fishing, apportioned the catch, and directed the ceremonies. In their ceremony over the first salmon that were brought in women and girls, not boys and girls, carried up the fish, men and women as well as children ate them, and the boys and girls who gathered up the bones lined up along the beach before marching into the water at a given signal and dropping them. They dried their second haul of fish on logs, the third and all subsequent ones on stagings [fish drying racks]. There was a ceremony at the first utilization of the stagings. All the people lined up with painted faces and feathered heads, and after the priest had chanted a prayer, made three feints as hanging up their fish before completing the operation. [at seasons end] the priest chanted a prayer and threw consumption plant seeds into the flames while the people piled all the refuse into the bonfire”.

Appendix 2

THE ORIGIN OF SALMON

Elders told a story focusing on Discovery Island:

“Once there were no seals and the people were starving; they lived on elk and whatever other game they could kill. Two brave youths said to each other ‘Let us go and see if we can find any salmon”.

They headed out to sea and after travelling for 3 1/2 months reached shore in a strange country. A man welcomed them and asked them to look outside where they saw smoke from qathmin plant [Lomatium nudicaule]: “that the steelhead, sockeye, spring and other varieties of salmon were burning, each for itself, in their houses. …[after a month their hosts said]… The salmon that you were looking for will muster at your home and start off on their journey. You must follow them’. So the two youths followed the salmon; for 3 1/2 months [which explains why they are absent for that period today]… Every night they took qathmin and burned it that the salmon might feed on its smoke and sustain themselves”.

They reached Discovery Island where they burned qathmin all along the beach as their hosts had said “to feed the salmon well” so “you will always have them in abundance”. But since they had no way of catching salmon:

“The leaders of the salmon, a real man and women, taught them how to make sxwala (purse nets), and how to use qathmin. …how their people should dress when they caught salmon, and that they should start to use their purse net in July, when the berries were ripe.”

Appendix 3

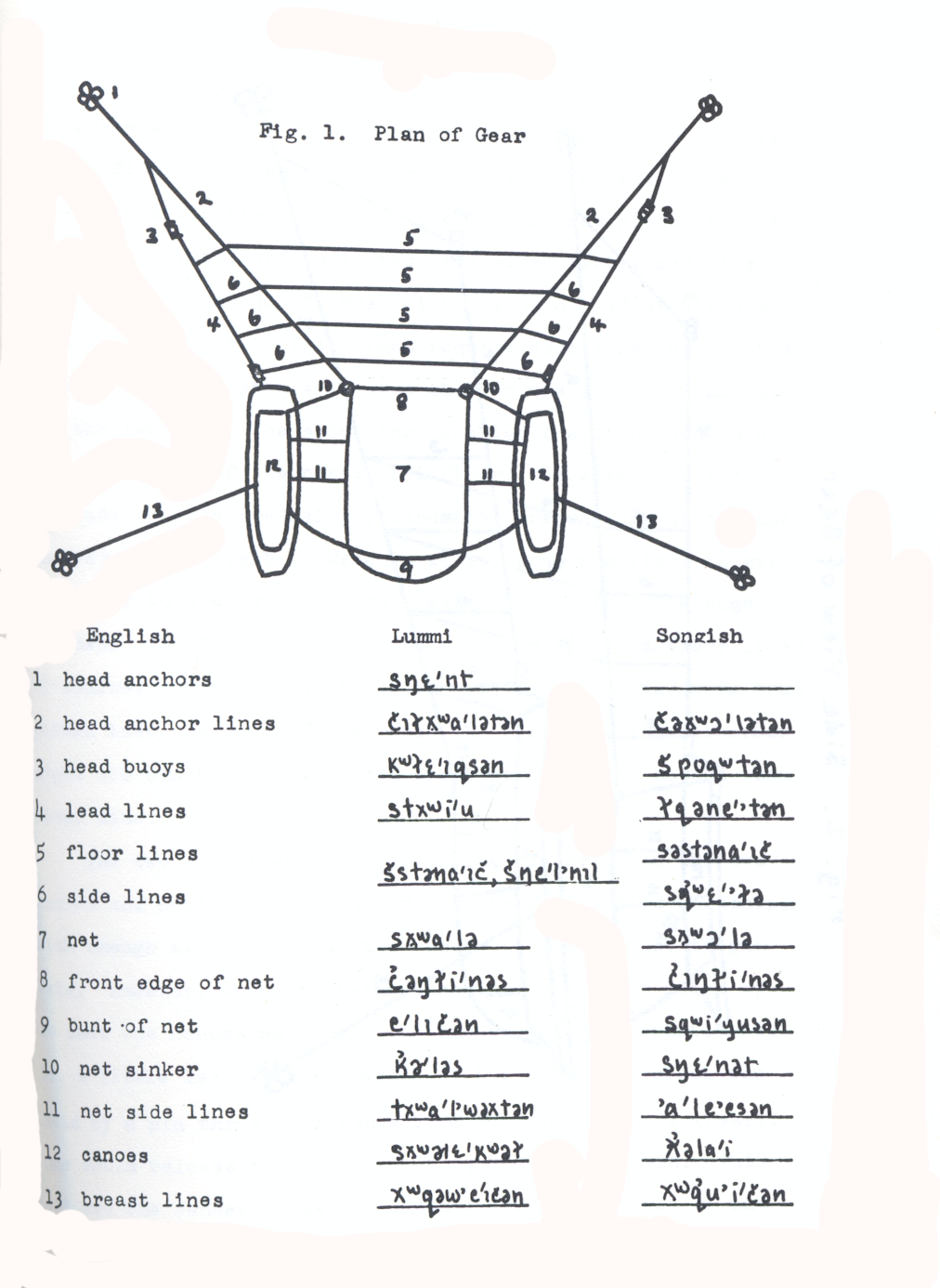

THE SXWALA (Sxole) or REEF NET

XEMŦOLTW̱ Nick Claxton of the W̱SÁNEĆ people has led the way to re-establish the practice of reef netting (see Claxton 2003; Claxton and de France 2018). In the 1930s to 1950s, Anthropologists worked with Lekwungen, W̱SÁNEĆ and Lummi people with reef netting experience to document their knowledge of the practice (Suttles 1951; Jenness 1934-35). Songhees, Tom James of Discovery Island could remember names of ten Lekwungen reef netting stations on San Juan Island that existed in the 19th century. In later times Archaeologists collected information from some of these reef netting locations (Moore 2012; Boxberger 1985; Moore 2012; Easton 1985 and 1990).

A large purse net called a sxwala or reef net was used for sockeye and pink salmon. The top and bottom ropes of this net were generally made from twisted cedar boughs, and the meshes from willow, gathered in May or June, peeled, and split into thin strands that were then twisted together to form a long rope. Blocks of light cedar held the net up and large rocks held the net in place. Several families cooperated by making sections of the net that could be later joined together at the fishing-grounds:

“The leader of the group then supervised the fishing, appointed one man to watch, with painted face and feathered head, which way the shoals were running, and apportioned the catch equally among the several families, without regard to their social rank. Each family then dried its share on its own rack. Not until all their requirements were satisfied did the leader provide for himself; but thereafter he appropriated the entire catch, which his followers cut up and dried for him.”.

Origin of the Willow Fish Net

A Story called the “Origin of the Willow Fish Net” was told by elder David Latess whose father was Songhees and mother was Tsartlip W̱SÁNEĆ (Saanich):

“A Saanich couple and their daughter joined some relatives on a fishing excursion to Blaine, Washington where the girl used to wander outside. One night while her parents were sleeping someone approached her and saw her again night after night”.

Wanting to know who it was, the girl smeared red ochre on her hands and rubbed it on the back of his clothing, which allowed her to identify him the next day.

Her suitor “urged her to go away with him, but she refused unless he first spoke to her parents”. Her father consented to their marriage only if “they remained for a time with her family”.

Soon after “fish became very scare, and the community was threatened by famine”. The youth asked his new wife to:

“Tell your father and his people to bring me a lot of sgwala. No one knew what he meant by sgwala; all the names… he gave to the various plants and animals were strange. They brought him bundles of one plant after another… until they brought him bunches of willow. From its bark he made a net sgwala, showed them how to use it and taught them the expressions that should accompany its handling. Then they were able to catch plenty of fish again”.

They became “prosperous once more” and the youth proposed to take his wife to his home. They embarked in a canoe “toward a very deep place in the sea not far from shore”, where they “vanished from view… Not many days later the girl reappeared above the surface of the water, showed herself to her people, and vanished again. … she never returned to them because she had married the fish-spirit sgwala.” (Jenness 1934-35).

References

Anderson, Alexander C. (1877). Indians. In: Guide to the Province of British Columbia for 1877-8, pp. 214-221, T.N. Hibben & Co.,

Bayley, Charles 1878. Early Life on Vancouver Island. Manuscript prepared for H.H. Bancroft, pp. 28-31. BCARS, E/B/B34.2.

Bancroft, Hubert H. 1887. History of British Columbia. 1792-1887. Vol. 32. The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft, San Francisco, The History Co. Pub.

Barnett, Homer G. The Coast Salish of Canada. American Anthropologist, Vol. 40, pp. 118-141, 1938.

Barnett, Homer G. Culture Element Distribution: IX Gulf of Georgia Salish. Anthropology Records, Vol. 1, No. 5. University of California Press, 1939.

Boas, Franz. 1916. Tsimshian Mythology. In: Thirty-first Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, 1909 – 1910, Washington D.C.

Boas, Franz. 1890. Second General Report on the Indians of British Columbia. Report of the Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, 1886-1889, 1890, pp.562-583. Reprinted in Northwest Anthropological Research Notes, Fall\Spring 1974, Vol. 8, No. 1\2.

Bogg, Edward B. 1867. The Fishing Indians of Vancouver’s Island. Memoirs of the Anthropological Society of London, Vol. 3, 1867-8-9, pp. 260-265.

Boxberger, D., 1985, A preliminary underwater survey of Legoe Bay, Lummi Island, Washington, IJNA 14.3, 211–16.

Canada. 1902. Department of Fisheries, (1902/02/04). Commission on the Salmon Fishing Industry in B.C. Evidence Session 15. George Cooper testimony, Feb. 4, 1902 and June 19,1904. RBCM Archives, GR213, file 1

Cannon, Aubrey and Dongya Y. Yang. Early Storage and Sedentism on the Pacific Northwest Coast: Ancient DNA Analysis of Salomon Remains from Namu, British Columbia.

Chavez, Francisco P., John Ryan, Salvador Lluch-Cota, M. Niquen. 2003. From anchovies to sardines and back: Multidecadal change in the Pacific Ocean. Science. 299. 217-221.

Claxton, XEMŦOLTW̱, Nick (2003) “The Douglas Treaty and WSÁNEC traditional fisheries: A model for Saanich Peoples Governance,” unpublished MA thesis, IGOV, UVIC.

Claxton and de France. 2018. With Roots in the Water. evitalizing Straits Salish Reef Net Fishing as Education for Well-Being and Sustainability. In: Indigenous and Decolonizing Studies in Education Mapping the Long View. Edited By Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Eve Tuck, K. Wayne Yang 2019. Routledge.

Cole, Douglas and Bradley Lockner. 1989. (editors) The Journals of George M. Dawson: British Columbia, 1875-1878. Volume 1, 1875-1876. Volume II, 1877-1878. University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver.

Colman, Mary Elizabeth. 1951. School boy at Fort Victoria. The Beaver. December 1951. Outfit 282:18-22. (Memoirs of Robert James Anderson.

Curtis, Edward S. Salish Tribes of the Coast. The North American Indian. Vol. 9, pp.175, Norwood, Mass., 1913.

Douglas, James. 1843. Diary of a trip to Victoria, March 1-2. RBCM Archives

Easton, N. A., 1985, The Underwater Archaeology of Straits Salish Reef-netting, unpublished thesis, Dept of Anthropology, University of Victoria.

Easton, N. A., 1990, The Archaeology of Straits Salish Reef-netting: Past and Future Research Strategies, Northwest Anthropological Research Notes 24.2, 161–77.

Finney, Bruce P., Marianne S. V. Douglas, Irene Gregory-Eaves, John P. Smol. 2002. Fisheries productivity in the northeastern Pacific Ocean over the past 2,200 years. Nature 416(6882):729-33

Finney, Bruce P., Irene Gregory-Eaves, Jon Sweetman, Marianne S. V. Douglas and John P. Smol. Impacts of Climatic Change and Fishing on Pacific Salmon Abundance Over the Past 300 Years. 2000. Science 290(5492):795-9.

Forbes, Charles. 1864. Notes on the Physical Geography of Vancouver Island, The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society, Vol. 34, pp. 154-171, J. Murray, London. (BCARS, NW910.6/R888/V.34).

Forbes, Charles. 1862. Prize Essay. Vancouver Island, Its Resources and Capabilities, as a Colony, Published by the Colonial Government, Victoria. (BCARS NW 971.IV/F692).

Grant, Walter C. “Reporting on Vancouver’s Island. Oct. 25, 1849. To James Douglas Acting Governor Ft. Victoria”. (BCARS A/B/20/G76).

Hebda Christopher F.G., Duncan McLaren, Quentin Mackie, Daryl Fedje, Mikkel Winther Pedersen, Eske Willerslev, Kendrick J. Brown, Richard J. Hebda.2022. Late Pleistocene palaeoenvironments and a possible glacial refugium on northern Vancouver Island, Canada: Evidence for the viability of early human settlement on the northwest coast of North America. Quaternary Science Reviews 279(1):107388

Hebda, Richard 2022.The story of Coastal Douglas-fir forests: An ancient legacy, a critical future. Raincoast. June 20.

Hebda, Richard J. 1997. Impact of climate change on biogeoclimatic zones of British Columbia. In Taylor, E. and B. Taylor. Responding to Global Climate Change in British Columbia and Yukon: Volume 1 of the Canada Country Study: Climate Impacts and Adaptation. Environment Canada and British Columbia Min. of Environment, Lands and Parks. Vancouver and Victoria. pp 13:1-15.

Hill-Tout, Charles. 1907. Report on the ethnology of the southeastern tribes of Vancouver Island, British Columbia. Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. vol. 37, pp. 306-374.

Jenness, Diamond. c.1934-35. The Saanich Indians of Vancouver Island. Unpublished manuscript #1103.6. Field Notes. Canadian Museum of Civilisation, Ms # 1103.6.

Lord, John Keats. 1866. Gossip About Man-Suckers. Hardwicke’s Science Gossip: An illustrated Medium of Interchange and Gossip for students and Lovers of Nature. London, Robert Hardwicke, 1866.

Keddie, Grant. 2003. Songhees Pictorial. A History of Songhees People as Seen by Outsiders. 1790 to 1912.

Keddie, Grant. 2019a. The Haultain Valley 14 Meter Ocean Standstill. grantkeddie.com

Keddie, Grant. 2019b. Wooden self-armed Fish Hooks from the Salish Sea. In: Waterlogged: Examples and Procedures for Northwest Coast Archaeologists. Washington State University Press, Pullman, Washington, 2019. Edted by Kathryn N. Bernick.

Keddie, Grant. 2016. A Lekwungen Herring Fishing site in Esquimalt Harbour. A Unique photograph in the Collection of the Royal B.C. Museum. RBCM Web Site.

Keddie, Grant. 2005. Fish Hook Shanks in the Archaeology Collection of the Royal British Columbia Museum from Southern Vancouver Island. RBCM Website.

Macfie, M. Vancouver Island and British Columbia, Their History, Resources and Prospects, 1865, p.430.

Mackay, John. 1899. The Indians of British Columbia. The B.C. Mining Record, Supplement.

McKechnie, Ian, Dana Lepofsky, Madonna L. Moss, V.L. Butler, T. J Orchard, and Gary Coupland. 2014. Archaeological data provide alternate hypotheses on Pacific herring (Clupea pallasii) distribution, abundance, and variability. Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences 111 (9). E807-E816.

Moore, Charles and Andrew Mason. 2012. Demonstration Survey of Prehistoric Reef-Net Sites with Sidescan Sonar, near Becher Bay, British Columbia, Canada. The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 41(1):179-189.

Price, John and Nick Claxton. “Whose Land Is It? Rethinking Sovereignty in British Columbia,” in BC Studies, 204 (Winter 2019/20). 89-113.

Rodrigues, Antonia T, Iain McKechnie, Donya Y Yang. 2018. Ancient DNA analysis of Indigenous rockfish use on the Pacific Coast: Implications for marine conservation areas and fisheries management. PLoS ONE 13(2): e0192716.

Stern, Bernhard J. 1934. The Lummi Indians of Northwest Washington. Columbia University Press, New York: Morningside Heights.

Stewart. Hilary. 1977. Indian Fishing. Early Methods on the Northwest Coast. J. J. Douglas Ltd., Vancouver.

Suttles, Wayne P. 1974. Coast Salish and Western Washington Indians I. The Economic Life of the Coast Salish of Haro and Rosario Straits, Garland Pub., New York, 1974.

Suttles, Wayne. 1998. Historic and Early Historic Fisheries in the San Juan Archipelago. Prepared for the National Park Service. May 1998.

Suttles, Wayne. 2001. Some Questions About Northern Straits. In: The Thirty-Sixth International Conference on Salish and Neighbouring Languages. Chillilwack British Columbia, Canada, August 8-10, 2001. Hosted by the Sta:lo Nation, Chilliwack B.C. in Conjunction with the University of British Columbia Department of Linguistics. The University of British Columbia Working Papers in Linguistics. Vol. 6:291 – 310.

Swan James G. 1857. The Northwest Coast. Reprinted by Ye Galleon Press. 1989, with an introduction by W.A. Katz.

Wilson, Captain Report on the Indian Tribes Inhabiting the Country in the Vicinity of the Forty-Nineth Parallel of North Latitude. Transactions of the Ethnological Society of London, Vol. IV, New Series, pp. 275-332, London, 1866.

Wood, James. 1851. Description of Juan de Fuca Strait. The Nautical Magazine and Naval Chronicle. A Journal of Papers on Subjects Connected with Maritime Affairs, January, London.

Whymper, Frederick. 1876. The Countries of the World: Being a Popular Description of the Various Continents, Islands, Rivers, Seas, and Peoples of the Globe, vol. 1, London: Cassel, Petter, & Galpin.