Halket or Deadman’s Island

(Please respect this special location and view it only from a distance).

On southern Vancouver Island it was common for, at least some, Indigenous families to place their dead, on small Islands. In historic, or post contact times, burials were placed on these islands in boxes, canoes or small shed-like structures. It is unknown how far back in time this practice extends. Underground burials were common before 1000 years ago.

One of these burial Islands, known to be used in the 19th century, was Halket Island in the Selkirk Waters above Victoria’s upper harbour. It is located north of the Point Ellice Bridge (Bay Street), between the foot bridge (old CN Railway trestle Bridge) on the west and the modern canoe facilities on the eastern shore. No Indigenous name was recorded for the Island.

Figure 1, shows a painting of Halket Island in the 1870s. The image view is looking south to downtown Victoria from west of Cecelia Ravine. The old railway trestle, coming from the Victoria West side and extending to the East of Cecelia Ravine was not here at the time.

Halket Island is first mentioned in the 1850, Vancouver Island treaties, as the “Island of the Dead”, and was believed to form the boundary between the “Kosampson” and “Swengwhung” families of the lək̓ʷəŋən peoples. It is marked on the early maps as Deadman’s Island and in 1851 as Halket Island.

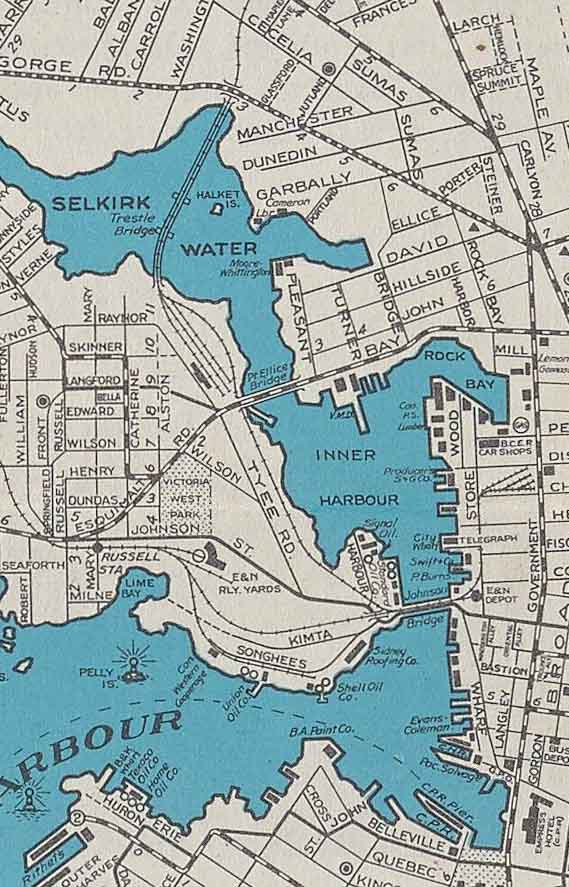

Figure 2, shows a 1938, city map with Halket Island in Selkirk Water. For many years Halkett Island was surrounded by logs waiting to be processed by the Cameron and Moore Whittington lumber mills, that can be seen close by. This undoubtedly perpetuated erosion of the soils and vegetation from the island.

Figure 3, shows a painting of Halket Island on June 26, 1857, by the American artist Lieutenant James Alden. One can see several small burial sheds and a human-like carving next to one of them. On October 5, 1858, the Victoria Gazette writes about Halket Island burial ground:

“The Songish tribe have another much larger repository for their dead, which is used at the present time. It is about three-fourths of mile above the Victoria bridge, on a small island, and only accessible with canoes. Many rude carvings can also be seen there, as well as piles of canoes, fragments of boxes, blankets, and every household article, …the corpse is packed in a box, without regard to length, breadth, or height [flexed burials], and covered down. The nearest friends then carry it to a canoe … which is prepared for the purpose, canoes proceed to the appointed place, which is always a detached spot some distance from the village.

(After the burial is put on the island), “Canoes have been observed to come frequently about twilight to the island named above, where a fire of sticks is kindled, and occasionally gum-wood and other combustible material are thrown on to it so that it burns till after midnight, till which time the Indians keep up an incessant (sound), that can be distinctly heard for a mile. There are other small isolated places where the dead are laid, but they are not greatly reverenced by the Indians, being repositories for the bodies of strangers, slaves, or the poor.”

In 1867, Edgar Fawcett with three other boys were bathing on Deadman’s Island. They lit a fire with broken coffin pieces. The fire got out of control and set the island on fire. The boy’s parents were heavily fined under the Indian Graves Protection Act. Fawcett describes the island as being “opposite Leigh’s mill”. This is James Leigh & Sons Lumber Mill, then at the corner of David and Pleasant streets. The island was covered in trees and shrubs and in the trees were corpses “fastened up in trunks and cracker boxes, but mostly trunks, the bodies being doubled up to make them fit in the trunk. Some were also buried in the shallow soil and surrounded by fences, and “boxes of corpses were piled one on top of the other.” One article reports that a popular coffin for small people was one of “Sam Nesbitt’s cracker boxes” (Fawcett 1912).

On July 2, 1867, the Victoria Colonist notes that the fire: “on Deadman’s Island destroyed the Indians graves and remains”. They indicate that the Island had been used as a burial place by the Songhees for many years. “Carved images, intended to represent departed chiefs, generally appeared at the side of the boxes. The favourite weapons, canoes, trinkets, and occasionally a few blankets, were deposited by the side of the corpse”. According to Fawcett, the Songhees were buried “at two points on the reserve”, but due to a smallpox outbreak, “the authorities insisted on the bodies being buried in soil.” Historic, Christian burial grounds were located on the reserve at Hope Point and Lime Point.

The island has caught fire several times since 1867, the last time being September 18, 1993. The island was formally created as a reserve in 1913, but was “cut off” as a reserve in 1924, by the Federal Indian Reserve Commission. It was formally recorded as an archaeological site, DcRu-55, in 1964 to ensure its protection. It was restored to the lək̓ʷəŋən through legal action, only in August of 1993.

Figure 8. Halket Island in 1990. Cormorant airing its wings on top of mast pole.

Reference: Fawcett Edgar. The Indian Burying Ground. The Victoria Colonist. March 24, 1912.