Introduction

Interpreting older Indigenous photographs can be a confusing problem for those not familiar with the history of photographers and the history of the collections in which they eventually end up. The same photographs are often given different information in different archives and in different publications. In the early 20th century, a common stereotype of older Indigenous people was for journalists to exaggerate their age. They were sometimes wrapped in blankets when photographed to cover-up the European style clothes they are wearing. They are often mistakenly presented in photographs as being over 100 years of age. I have the advantage over journalists of the past, in having easier access to examine baptism, birth, marriage and death records from church and government sources dating back to the mid-19th century. On a number of occasions, I was able to demonstrate that those labelled as being over a hundred were only in their 80s.

Only sometimes, are anglicized names of Indigenous people provided in early photographs, and even rarer, their indigenous names. The latter are known to change, as a cultural practice, in a person’s lifetime, and when recorded, they are often anglicized in different ways, making it difficult to trace them in written documents.

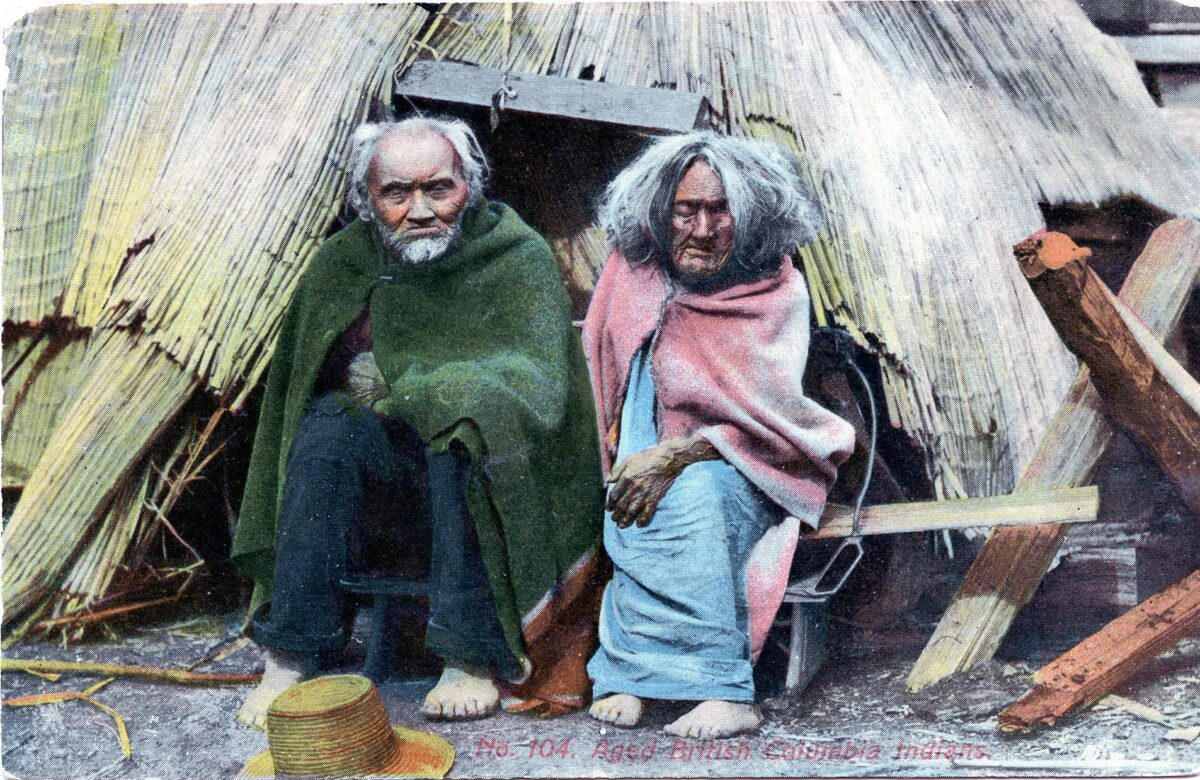

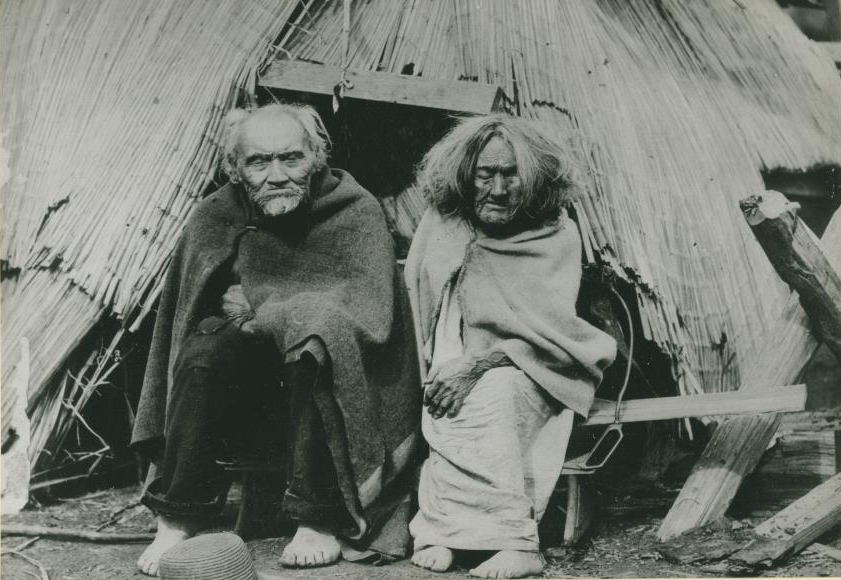

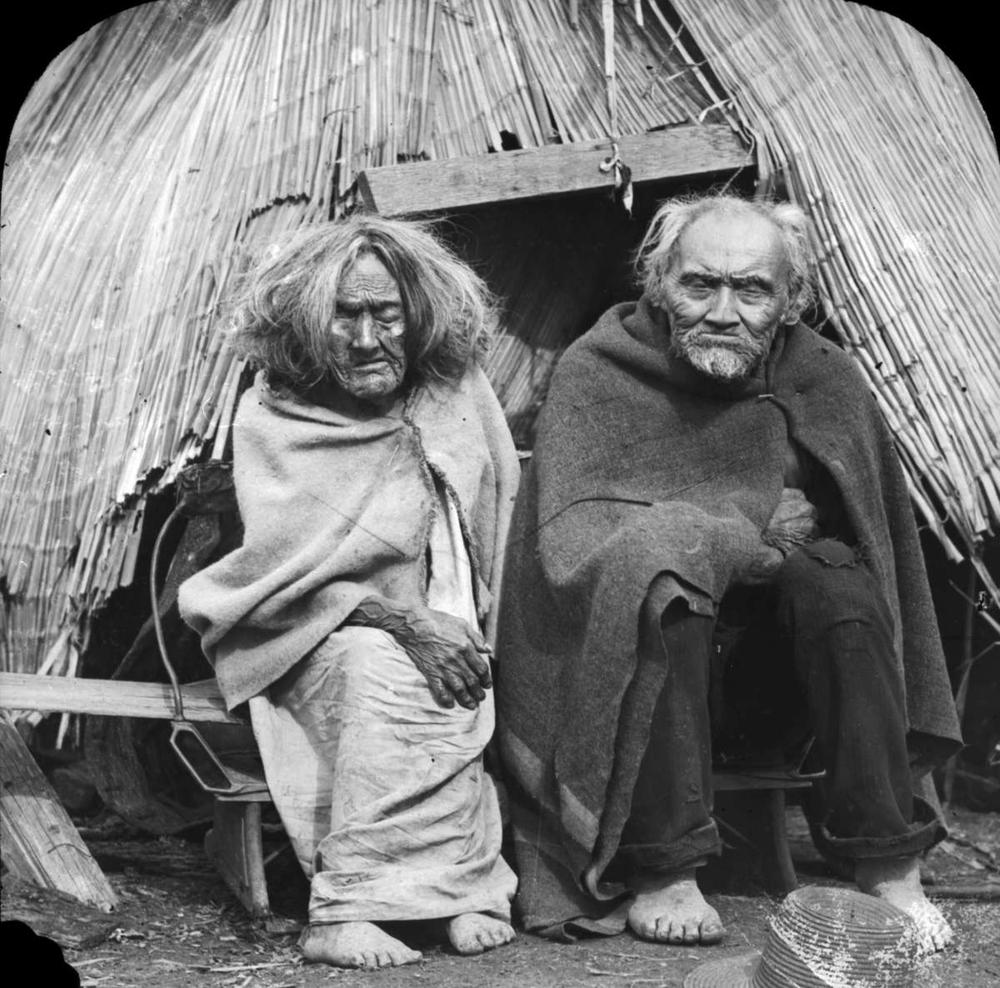

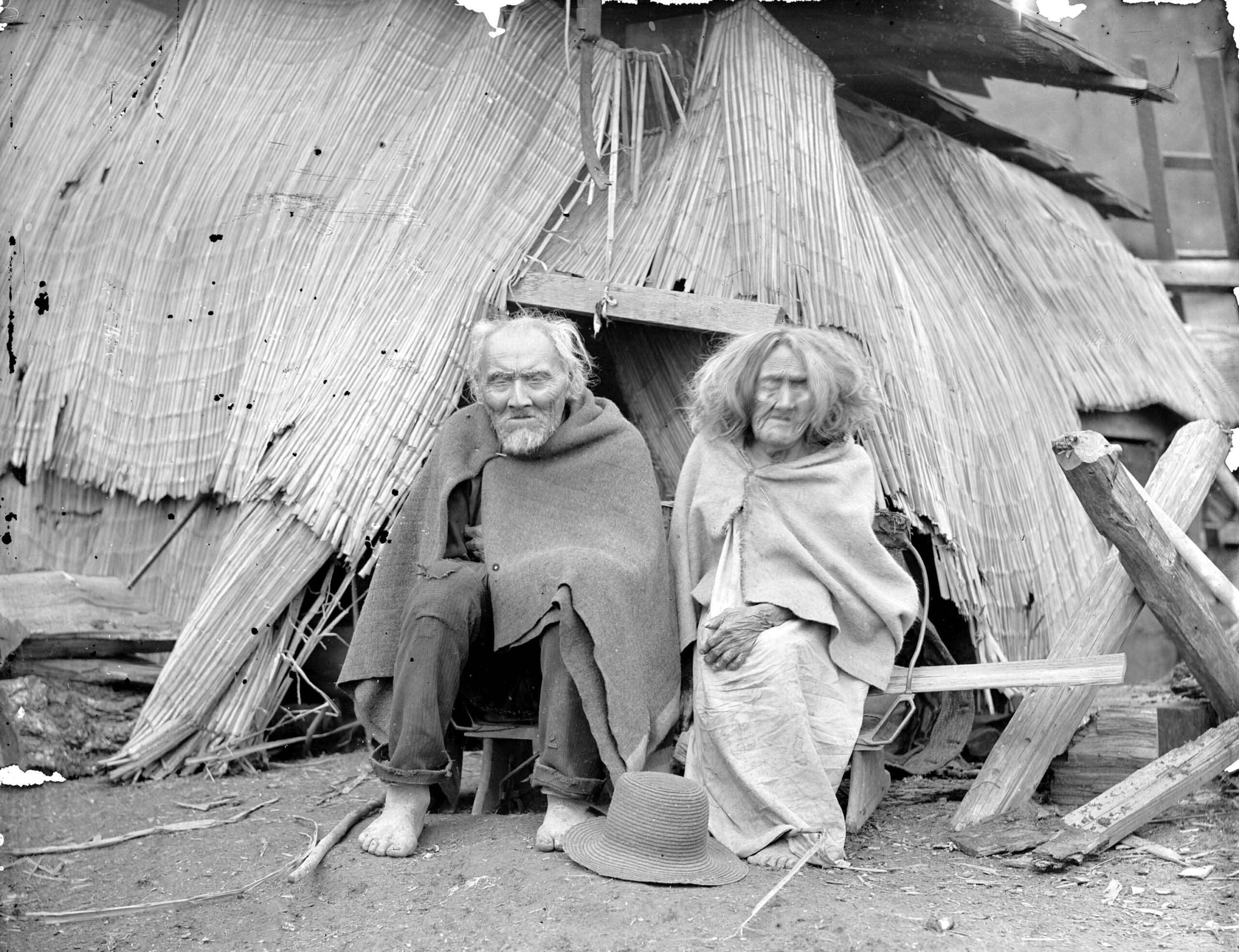

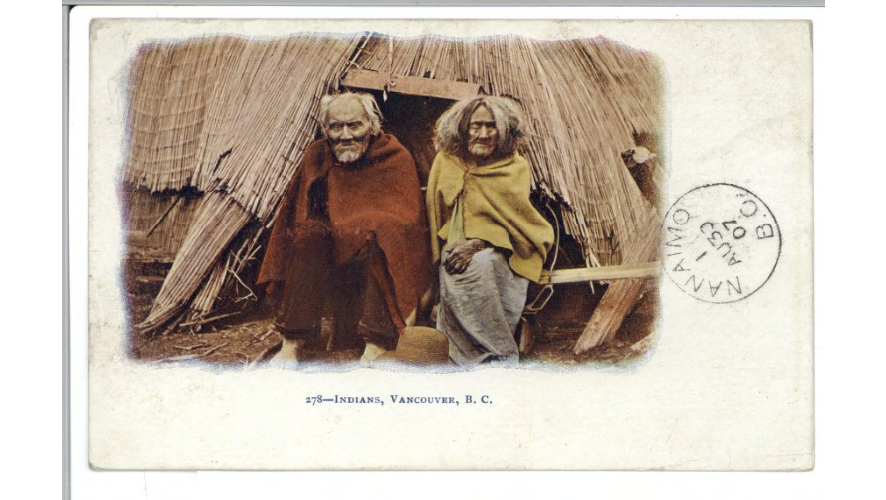

The images here, of two elderly Indigenous people, show an example of confusion that has arisen in documenting old photographs. I was determined to find out the dates of these photographs and find the correct name(s) of the old couple. This particular photograph is of significance as it is linked to a story of an individual and traditional cultural practices told by an Indigenous woman about the man in the photograph referred to as the “Fish Charmer” (see Appendix 1). I discovered that there were two similar, but different, images of this couple sitting in front of a temporary shelter. These images have been mistaken with each other because they are so similar. I will refer to them as View #1 and View #2. There are several versions of both of these that have been cropped or reduced from the full image when published. Some prints have been mistakenly copied from the reverse of View #1. The use of photographs on postcards became prominent from 1900 to 1912 in British Columbia. Because there were so many post cards made, they have often survived while the original glass negative and prints have disappeared.

View #1 Photograph

My interest was first sparked when I purchased an old postcard in the 1970s (figure 1). On the front of the card is: “No. 104. Aged British Columbia Indians”. It was produced by T. N. Hibben & co., Victoria, B.C., but printed in Saxony, Germany where, at the time, Germany had better quality paper for silver printing. Another matching postcard has a stamp date of April 14, 1907, and has the caption as “Aged B.C. Indians”. I have seen, at least eight similar examples of this View #1. It is important to understand, that inexpensive postcards were acquired by Indigenous peoples, discussed among themselves, and became part of the extended memory of those people that may have been passed on in future stories.

The Oldest Recorded Date 1899

The earliest use of this image I have found, so far, was in an 1899, publication by Joseph William McKay (McKay 1899). This image showed a larger version, from top to bottom and side to side than my 1907, published postcard. Joseph McKay (January 31, 1829 – December 21, 1900), was a fur trader of the Hudson’s Bay Company and later Indian Agent, He came to Victoria in 1849. In 1850 he helped James Douglas negotiate the Victoria Treaties and the next year was sent to explored the Cowichan valley. In 1852-1854 he worked for the Hudson’s Bay Company at Nanaimo where he negotiated a treaty and took charge of the coal mines. His parents were both Metis and his involvement with Indigenous peoples was extensive throughout his life (Mackie 2003).

McKay’s experience would suggest that his information on names would be trustworthy. He was acknowledged by Indigenous people in being fluent in several of the languages in the Salish language family and the Chinook trade language. In his writings, such as in the Fort Nanaimo Journal, he showed that he was aware of the Indigenous names of many individuals. The caption that McKay provides for his published image is: “Chilarin (old man) and Tol Ramault (old woman) of Somenos village – both over 100 years old.” (McKay 1898).

A Different Version of the Same View #1 Image

There is another version of the same image, recorded as PN05920_c, in the Royal B. C. Museum Ethnology photo collection. It is catalogued as N0. X928 – xxI/35, from the Charles Newcombe collection (Figure 2). The date on the photo card is “received 1932 ex Mrs. Cryer”. It is an “Original glass plate positive. Photographer unknown”. It has a reduced extension of the image on the top and bottom. This same image is also printed in reverse in the RBCM Archives as F-05165, HP093310, and has a more restricted view (Figure 4). This photograph view, in some form, was clearly owned at one time by William Henry Lomas, the Indian Agent at Duncan. The associated copy indicates it was: “In frame with groups of photos: Property of a daughter of the late M. W. Lomas, first Indian agent at Duncan”.

It is listed by the RBCM Archives as: “Part of A.H. Maynard collections” and Maynard is listed as the “creator”. This is Albert Hatherly Maynard (1857-1934]. We know that Albert Maynard had many photographs in his collection that came from other photographers, including his father, Richard Maynard. We cannot be certain who took this photograph.

Comments on the ethnology photo collection card for the same image view, notes that F-05165 is: “Tow-kau-ahl, the fish charmer, and his sister Taul’kun, Duncan.” This information is from the manuscript of Beryl Cryer: “The Fish Charmer”. In: The Indian Legends of Vancouver Island. [BCARS F8.2/C88] and her publication from this, in The Victoria Daily Colonist of March 20, 1931 (see Appendix 1).

The PN05920 back card, has a penciled note from W.H. Olsen, Nov. 17, 1980. “My copy of this photo was sent to me by Mrs. Beryl Cryer from Ontario 20 years ago. Her notation on the back reads” ‘Tow-kau-ahl, the fish charmer, and his sister Taul-kun’. It is my understanding at this time that the photo was taken at the head of Chemainus Bay. This seemed likely, since her older brother, Frank Halhed, took a large number of glass plate photos in the immediate area pre-1900. With this picture came several other photos, now in B.C. Archives, collected by Mr. Lomas, the former Indian Agent for the Duncan area. Most of these had been taken at the various reserves of Duncan to Cowichan Bay. This probably accounts for the confusion, but of course, does not resolve it. It seems to me that only Mrs. Cryer could set the record straight but, since she was elderly 20 years ago, she may not be living.”. Given we know the image was taken earlier (before 1899), than thought at the time of this note, this will not be a Frank Halhed photograph.

Also, on the back of the Ethnology photo card is a confusion of both typed text, and later, different sets of hand written commentary. It mistakenly gives the photographer as “M. McLomas”, ? Cryer Coll’n”. Typed: “Left to right: Towauahl and his sister Taul-kun of the Someeno [Somenos] band. He was the fish charmer People”. Hand written : (1) “Mrs Cryer was told by Mary Rice” (2) “In Mr. Lomas photo coll.” – from print in file envelope.” (3) See. Same photo, Vancouver Public Archives, In P178, here it is listed as ‘Kamloops, circa 1900’. “ (4) “according to J. Elliot, Aug. 13/76, this was taken opposite Sands Funeral Parlour, Duncan”. (5) see catalogue sheet for further info. Collected by David L. Rozen, May/June, 1977”. This B/W print also has: “Original property of Mr. Lomas, Duncan”. Copy from Mrs. Cryer”.

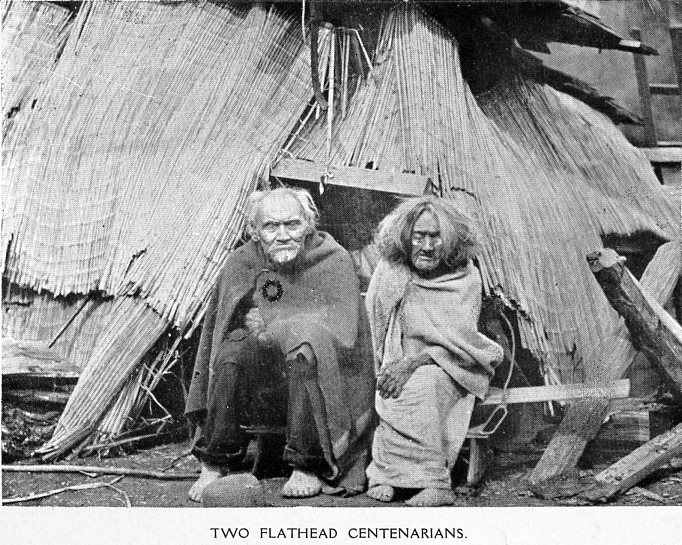

A slightly larger view of RBCM PN05920, was used in the 1907, publication of missionary Thomas Crosby, with the caption: “Two Flathead Centenarians” (Crosby 1907). It has the upper portions of the image more like the 1898, published image but is reduced on the bottom portions (Figure 3).

A different version of view #1 (Figure 4), was mistakenly printed in reverse and given a different catalogue number. RBCM Archive F-05165_141.

View #2 photograph

The image referred to earlier on the back of PN05920, as being in the “Vancouver Public Archives”, is in fact, not the same image of View #1, but an original version of another different, but similar image, taken at the same time. It is Vancouver City Archives (Reference code: AM54-54-: LGN 633. Old Photo Number: In P178.2N121.2. Item 189-7). It is a large B/W glass negative (20X 26cm). It was acquired from the collection of James Skitt Matthews (1878-1970), Vancouver’s City archivist, who started his job in 1933. It is stated: “J.S, Matthews notes with print or negative in Archives”. The description has “[Elderly Native Indian couple seated in front of rough shelter]”. It is listed as a photograph of Norman Caple (1866-May 13, 1911).

The differences of the two images includes the location of the man’s hat on the ground in a different position: the sticks on ground are in different positions or absent; the man’s hand and head position has slightly changed and the woman’s feet position are different. The glass negative of the View #1 image would have been taken by the same photographer as this view #2. This view #2 photograph was also used in the production of post cards. One from the Simon Fraser University Library, Philip Frances Collection, MSC130-1553-01, is dated August 30, 1907, and labeled “Old man and woman in front of tepee” (Figure 6).

A later image of the same people?

There is another photograph that appears to be the same couple (Figure 7). This shows them sitting together on the grass. RBCM Archives H-07045. (Accession number: 198904-002). The caption on the image is: “Casper Kapiel & wife: centenarians of Cowichan I.R.” Under the line for name of creator is: “Royal Commission of Indian Affairs for the Province of British Columbia (1913-1916). Page 5. At the commissions first meeting with Indians.” This date would be May 25, 1913. From Royal Commission on Indian Affairs photograph album. However, we need to consider that the Commission album may have included older photographs. This looks like the same couple in the other images, who are now wearing hats. The man in this image is wearing the same style of hat as can be seen on the ground in the other images. This is a subject that needs further investigation.

Discussion

Photographer Norman Caple did start taking B.C. images after 1892 and later joined with R.H. Trueman and Company to become Trueman and Caple of Vancouver. However, I would suggest that the Vancouver City Archive image LGN633, may not be a Norman Caple photograph. As he did almost all of his photographing around Vancouver and other parts of the Mainland of B.C. and only one or two when visiting Victoria, and no others further up Vancouver Island.

Mary Rice (“Tzea-Mntenaht” or “Siamtunaat”), the story teller, was born in 1855 and would be about 40 to 45 years old when the elderly couple in the images were alive, but she said she never saw them, and only heard about them from her mother when telling the story of the Fish Charmer. The photographic print or post card that Beryl Cryer showed Mary Rice was earlier in the possession of Indian Agent William Lomas, but how Cryer received it is unknown. The census of Indigenous Cowichan tribes (Kwa’mutsun, Qwum’yiqun’, Xwulqw’selu, S’amunu Lhumlhumuluts’, Xinupsum, Tl’ulpalus), for 1881, includes mostly anglicized versions of Indigenous names, but none of these, even remotely, match the names recorded by Cryer. If the older couple were “both over 100 years of age” in 1899, they would have likely died in the next five years. There does not appear to be anyone that would fit their description on the death records around this time. In the 1900 to 1905 time period, there were only a few people that died at age 80, in the general region. Possibly Mary Rice’s mother gave names from a much earlier times to tell the story of the Fish Charmer, and there was the assumption that the people in the image were those mentioned by her mother.

The name Casper Kapiel, linked to the image of figure 7, has a similar sounding name with a first name “Ka pel” recorded for a person in the 1881, Kwa’mutsun census.

Appendix 1. The Fish Charmer Story

Preface to Appendix

This story was written for a newspaper article by Beryl Cryer from interviews with May Rice of Kuper Island. For writing her article called The Fish Charmer. Beryl Cryer showed the View #1, image shown here, to Mary Rice before March 20, 1931, when she had her article published (Cryer 1931). How much artistic license was used in writing this story is difficult to tell. Cryer’s interjection of questions likely altered the nature of the story and some of her additions may have been part of a need to include a longer version of the story. For a more detailed analysis of Beryl Cryer’s writings and the context of this story, see the book on Cryer compiled and edited by Chris Arnett, Two Houses. Half Buried in Sand (Cryer 2007).

The Fish Charmer Story

“ ‘Ah! Those people’ she said as she took the photograph. I know about them. ‘There were four in that family, three brothers, and one sister, and I think they never married, just all live in one little house. This man here”, she tapped the photograph with a withered old finger. “He was called Tow-Kau-ahl, and his sister her name was Taul-kun. They were ‘Samuna’ Indians and very, very old. Well, the story I can tell you about Tow-kau-ahl is true because lots of people who knew him saw him do this thing, but I never saw him only ‘remember my mother telling me about him”. This man could do a thing that not many Indians knew about. He had bad eyes, and no one could look at him for long, it made them frightened. Well, you do know this Tow-Kau-ahl never wanted anyone to fish in the Cowichan River”. The fish are all mine he told the Cowichan. ‘No one must fish in this place’. And he would look at the men who wanted to fish and they would go back to their houses and put away their nets and spear, and wait for him to bring fish to trade them.

Do you know what that man did?” She asked me. ‘Well, l’lI tell you. He charmed the fish’.”.

She paused for me to express my astonishment, “How did she charm them?” I asked. “Ah” she laughed, ”now listen. That man had a rattle, it was like a bird made of wood. Oh, it was such a nice one, with pictures cut on it. Early in the morning before the sun came, Tow-kau-ahl would take this rattle and walk through the woods until he came to the river. Here he would sit on the bank where it was high over the water, and he would sing and sing and shake his rattle, calling to the fish, telling them what he wanted to do.”

“What did he say to them?”, I asked.

“Well, I was told he called something like this. ‘Oh!, fish go up the river, do not go down into the sea. But run and go up, go up, go up! When you have gone far up where no people will follow, lie still and wait-I will come for you. Wait until tonight, then I will come! But turn away from the big sea, and go up, go up”.

Siamtunaat recited this in a curiously, toneless sing-song, and I could imagine the old man with his “bad” eyes crouching on the river bank, shaking his rattle and charming the fish.

“Do you think the fish did as he told them Siamtunaat?” I asked. “Why, yes!”. I know they did,”, she answered seriously. When they hear that man Tow-kua-ahl singing to them, they all waited, listened to his voice, then, rounded they turned and up the river they went, swimming hard against the water that was coming down. “All day long he would sit there, making his charm, and, when it was getting cool he would take his fish net and go far, far up the river to a place he knew about, and there he would catch more fish than he could carry.”.

“What net did he use?”, I asked. “Well, in those days my people used a net made of willow bark, or sometime that strong sort of grass, that grew up the Fraser River (Indian Hemp). The net the man had, was about one fathom long, or a little more (curiously enough, Siamtunaat generally gives measurements in fathoms), and it was made like a big sort of bag, with a big hole for the fish to go in. Tow-kau-ahl used to throw his net out into the river, and then he would throw stones as far up river as he could, to frighten all the fish into his net, then quickly he would draw the hole shut with a line fastened to it, pull in he net and take out his big fish. Back to his little house made of rushes he would take them, and there he would smoke and dry them for the winter.

“Now, as I told you, this man did not like any other person to catch the fish, and if he found other men had been fishing in his river, my, he was mad! He wanted to have all the fish for himself, so that he could trade them to the other Indians for blankets, clothes and food.

“When Tow-kau-ahl was very, very old his sister died, and then he and his brothers went to live on an Island near Seymore Narrows, and soon after that they, too, all died, and now there are none of my people who know how to charm the fish!.”

References

Crosby, Reverend Thomas. 1907. Among the An-ko-me-nums or Flathead Indians of the Pacific Coast. Toronto, Williams Briggs.

Cryer, Beryl Mildred. 2007. Compiled and edited by Chris Arnett, Two Houses. Half Bried in Sand. Oral Traditions of the Hul’Q’umi’num’ Coast Salish of Kuper Island and Vancouver Island. Talonbooks.

Cryer, Beryl, c. 1931. The Fish Charmer. In: Indian Legends of Vancouver Island. BCARS F8.2/C88.

Cryer, Beryl, 1931. The Fish Charmer. The Victoria Daily Colonist. March 20, 1931.

Mackay, J. W. The Indians of British Columbia. A Brief Review of Their Probable Origin, History and Customs. The B.C. Mining Record. 1899. Christmas Supplement.

Mackie, Richard. 2003. “McKay (Mackay), Joseph William,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003.