In 1969, I was part of the Simon Fraser Universities first Archaeological field school camped in the remote Kwatna Inlet. As I read every word of both volumes of Thomas McIlwrath’s classic study of the Nuxalk people of the Bella Coola Region (McIlwraith 1948), I wondered if those large birds mentioned in the mythology could be based on earlier occurrences of the California Condor or even an earlier relative of the Condor.

I knew a few Condors had been sighted in British Columbia in the late 19th century (Fannin 1891; Rhodes 1893), but some biologists had suggested that these were extremely rare migrants from the south. At that time, no Condor bones had been found in British Columbia. But this is no longer the case.

A Bone from Pender Island

On March 16, 2005, an approximately 2,920-year-old tarsometarsus bone of a condor was found in the Archaeological shellmidden site DeRt-4, at Poets Cove on Bedwell Harbour. These are the first California condor (Gymnogyps calilfornianus) remains found in an archaeological site in British Columbia.

The bone was from midden that was bulldozed during a construction project. The bulldozed piles were sifted through to recover faunal remains. This bone was recorded as “1686. Pender Pile A. Monitoring. 16 March 2005” (Wilson et. all. 2006).

Figure 3, shows a Condor tarsometatarsus bone that is more complete than the archaeological example found on Pender Island.

The tarsometatarsus is a foot bone between the intratarsal (ankle) joint and the bones of the toes. In birds, it consists of the distal tarsal bones (the heel in Humans) fused together with the metatarsal bone (the foot bones down to the toes). It is longer than a human foot, which results in it being mistaken as a leg bone rather than a foot bone.

The bone was identified by Becky Wigen, then curator of the bone lab in the University of Victoria Department of Anthropology, during faunal analysis of material from the site.

A radiocarbon date of 2920+/- B.P. (UCIAMS) was obtained from the bone. It is now located in the Royal B.C. Museum Zoology collection repository.

The Condor’s Extirpation

The California Condor (Gymnogyps californianus) with its wingspan of 3 meters, is the largest New World Vulture in North America. It is not closely related to Old World Vultures. The California vulture, whose fossil remains go back 40,000 years, is the only living member of the genus Gymnogyps. Gyps is the Greek word for vulture and Gymno, is Greek for naked or bare (Snyder and Synder 2000; Emslie 1988).

During the late Pleistocene 15,000 years ago, the condor’s range extended across much of Western North America. The radiocarbon data indicate that this species became extinct in the Grand Canyon, and other parts of the inland West by 11,000 years ago, with the disappearance of the megafauna, the condor’s main food source. (Emslie 2024: 1990; 1987; Chamberlain et. al. 2005).

Live Condors in British Columbia

At the time of the arrival of European settlers the condor ranged along the Pacific Coast from British Columbia through Baja California, Mexico.

In British Columbia the biologist John Keats Lord, while in B.C. from July 12, 1858 to February 28, 1860, noted that Condors occurred on the: “Mouth of the Fraser River. Seldom, visit the Interior” (Lord 1866).

John Fannin, Curator of the Provincial Museum, noted: “In September, 1880, I saw two of these birds at Burrard Inlet. It is more than probable they are accidental visitants here.” (Fannin 1891;1898). Later, Fannin observed on September 10th, 1896, in the Bow River valley, “between Calgary and the Rocky Mountains two fine specimens of the California Vulture, …I was not aware that this bird was found east of the Rocky Mountains, or so far north as the point above mentioned” (Fannin 1897).

William F. Tolmie observed groups of condors at a deserted Indigenous village on November 24, 1834, at Fort McLoughlin, near Bella Bella, on the central coast of British Columbia (Tolmie 1963). There are a number of other possible sightings. Pierre-Jean De Smet saw what appeared to be Condors at Canoe River, in the southern Interior of the Province, around September 4, 1845 (De Smet 1978).

Their Disappearance and Recovery

Condors become very rare north of California by 1850. By 1940, the range had been reduced to the coastal mountains of southern California with nesting occurring primarily in the rugged, chaparral-covered mountains, and foraging in the foothills and grasslands of the San Joaquin Valley. The species was last seen in Oregon in 1904 (Koford 1953). They were recognized as an endangered species in California law as late as 1971. They were almost wiped out in the 1980s when their wild population numbers dipped to just 23 individuals. They became extinct in the wild around 1987. Starting in 1992, Zoo bred Condors began to be released back into the wild (Snyder and Snyder. 2000).

Captive breeding programs were able to slowly grow the number of California condors to more than 300 wild birds living in central southern California deserts. In 2003, tribal elders of the Yurok Tribe, who considered this bird as having both cultural and ecological importance, worked with the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service to focus on bringing this species back to the Pacific Northwest (Snyder and Snyder 2000; U.S. Fish and Wildlife Reports 2013).

Indigenous Use of Condors

In the U.S. there is debate as to whether or not condor use for cultural practices depressed their populations before the arrival of Europeans. Ceremonial killings were routine among some Indigenous tribes and were forbidden to be killed in others (D’Elia and Haig 2013). In southern California, Condors were killed in ceremonies to honour the memory of important leaders. Condor dances, used skins and feathers (Figure 4 & 5). The skins were used to make skirts that were retained as important ritual objects by their Indigenous owners (Bates et.al. 1993:41; Bates 1982). Ceremonies were held by the Gabrilieño, Cahuilla, Kumeyaay and Cupeño tribes (Kroeber 1907; 2002).

Figure 4, shows A skirt of California Condor feathers held by Edwin Davis of Mesa Verde (San Diego County, California). After Carl B. Koford 1940. University of California Berkeley, Museum of Vertebrate Zoology. MVZ record #101151.

Condor body parts were used in initiation ceremonies for new shamans and rituals to cure disease. Central Miwok shaman acquired powers from condors that allowed them to suck supernatural poisons from their patients.

Dwight Simons has summarized the occurrence of Pacific coast condor remains in an archaeological context. He reports on 13 sites between Oregon and California spanning a time range between approximately 10,000 years ago and early historic times. The greatest number of individual California condor bones has been recovered at the “Five Mile Rapids” site in Oregon dating to 8,000-9,000 years old. There the unmodified remains of 63 birds were present. They were found at the Dalles site on the Columbia River dating to 4,000 to 8,000 years ago. Flutes made from wing bones have been found in central California archaeological sites. (Sharp 2012; Simons 1983).

Discussion

Brian Sharp documents mid-19th century sources indicating there were many Condors along the Columbia River. They were seen there during the Fall salmon runs eating the dead fish, and around Indigenous villages, eating the offal of fish thrown out around the villages. He argues, based on the historic sources, that the Condor were likely year-round occupants in the Pacific Northwest and nested here (Sharp 2012).

In trying to interpret weather an Indigenous story pertains to a Condor, or a modern Turkey vulture or eagle can be difficult. With the absence of Condors during the recording of Indigenous stories, misinterpretation of which species is referred to may be likely. There is a need for a linguistic study that examines the names and meanings presented by Indigenous people from British Columbia to California.

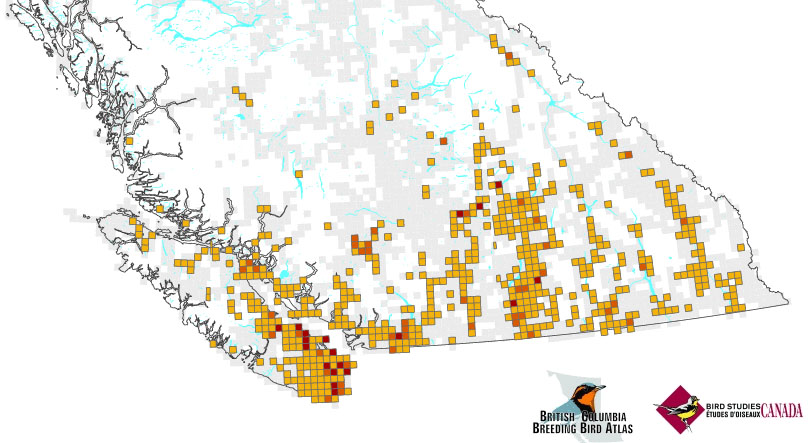

Turkey Vultures, Cathartes aura, (Figure 6) breed across southern British Columbia and Vancouver Island, but they mostly winter well to the south. Their larger presents this far north in more recent years, may be a result of warming climate, the increasing deer populations, and increases in carrion along larger road networks. It is likely than Condors in the past would have occupied a similar range (Figure 7).

References

Bates, Craig T., Janet M. Hamber and Martha J. Lee. 1993 The California Condor and the California Indians. American Indian Art 19 (1): 40-48.

Campbell, R. W., Dawe, N. K., Cooper, J. M., Kaiser, G. W., and McNall, M. C. E. 1990. Birds of British Columbia. University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver.

Chamberlain, C. P., J. R. Waldbauer, K. Fox-Dobbs, S. D. Newsome, P. L. Koch, D. R. Smith, M. E. Church, K. L. Sorenson, and R. Risebrough. 2005. Pleistocene to recent dietary shifts in California condors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102(46):16707-16711.

D’Elia, Jesse and Susan M. Haig. 2013. California Condors in the Pacific Northwest. Oregon State University.

Davidson, P.J.A. 2015. Turkey Vulture in Davidson, P.J.A., R.J. Cannings, A.R. Couturier, D. Lepage, and C.M. Di Corrado (eds.). The Atlas of the Breeding Birds of British Columbia, 2008-2012. Bird Studies Canada. Delta, B.C.

Demers, M., Blanchet, F. N, Bolduc, J. B. Z, and Langlois, A. 1856. Notices and Voyages of the Famed Quebec Mission to the Pacific Northwest (C. Landerholm, translator). Ore. Hist. Soc., Portland, OR.

De Smet, Pierre-Jean. 1978. Oregon Missions and Travels over the Rocky Mountains in 1845–46. Reprint of 1847 edition. Ye Galleon Press, Fairfield, WA.

Douglas, David. 1904. Sketch of a journey to the northwestern parts of the continent of North America during the years 1824–25–26–27. Ore. Hist. Quarterly 5:230–271, 325–369.

Douglas, David. 1959. Journal Kept by David Douglas during his Travels in North America, 1823–1827. Antiquarian Press, New York

Emslie, Steven D. 2024. An Early Condor-Like Vulture from North America. The Auk. Vol. 105, Issue 3. Article 17.

Emslie, Steven D. 2024. A late Pleistocene nest cave of Gymnogyps californianus (California Condor) in Texas: New radiocarbon and stable isotope analyses. Ornithology Vol. 141, Issue 4.

Emslie, Steven D. 1987. Age and Diet of Fossil California Condors in Grand Canyon, Arizona. Science. Vol. 237. Issue 4816:768-770.

Emslie, Steven D. 1990. Additional Carbon 14 dates on fossil California condors. National Geographic Research 6(2):134-135.

Fannin, John. 1891. Check list of British Columbia birds. Queen’s Printer, Victoria, B.C.

Fannin, John. 1897. The California Vulture in Alberta. Auk. Vol. 14, Issue 1. Article 19:89.

Fannin, John. 1898. A Preliminary Catalogue of the Collections of Natural History and Ethnology in the Provincial Museum, Printed by Richard Wolfenden, Printer to the Queen’s Most Excellent Majesty, Victoria, British Columbia. Page 33.

Koford, C. B. 1953. The California Condor. National Audubon Research Report. 4, 1–154 (1953).

Kroeber, Alfred L. 1907 Indian Myths of South-Central California. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 4 (4). p. 220.

Lord, John Keast. 1866. The Naturalist in Vancouver Island and British Columbia, vol. 2. Richard Bentley, London.

McIlwraith, Thomas F. 1948. The Bella Coola Indians. Vol. 1 & 2. University of Toronto Press Incorporated. Toronto.

Rhodes, S.N. 1893. Birds Observed in British Columbia and Washington State in the Spring and Summer of 1892. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 45:21-65.

Simons, Dwight D. 1983. Interactions between California Condors and Humans in Far Western North America. Pages 470-494. In: Vulture Biology and Management, Sanford R. Wilbur and Jerome A Jackson, (eds). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Sharp, Brian E. 2012. The Condor in Northwestern North America. Western Birds. Vol. 43, No. 2:54-89.

Snyder, Noel F and Amadeo M. Rea. 1998. California Condor. In: The Raptors of Arizona, Richard L. Glinski, ed. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Snyder, Noel and Helen Snyder. 2000. The California Condor: A Saga of Natural History and Conservation. San Francisco: Academic Press.

Tolmie, William Fraser. 1963. William Frasier Tolmie, Physician and Fur Trader. Mitchell Press, Vancouver, BC. Page 185.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Reports. 2013. The California Condor (Gymnogyps californianus). 5-Year Review.

Wilson, et. al. 2006. Archaeological Studies. DeRt 4, Poets Cove at Bedwell Harbour. Pender Island, B.C. Heritage Conservation Act Site Alteration Permit 2002-388. Prepared for Poets Cove at Bedwell Harbour Limited Partnership. 9801 Spalding Road. Pender Island, B.C. VON 2M3. Prepared by Ian R. Wilson, Becky Wigen, Ian Streeter, Andrew Hickok, Erin Willows and Jenny Storey, May 2006. I.R. Wilson Consultants Ltd.