Originally published in Datum. Newsletter of the heritage Conservation Branch. Ministry of Recreation and Conservation. 1978. 3:2:3-5.

By Grant Keddie. 1978.

Introduction

Early Chinese coins have been used occasionally to date historic burials or associated historical assemblages as well as being used as proof of a pre-contact circum-Pacific movement of trade goods or of proof of actual visitations by early Chinese explorers. By utilizing the direct historic approach it becomes evident that we must exercise caution in using Chinese coins as chronological indicators. I first became aware of the need to examine the reliability of dating with Chinese coins when trying to date a historic burial intrusion at the archaeological site DhRx 6 on Newcastle Island near Nanaimo. B.C. A burial in a wooden coffin nailed together with square-headed nails was associated with three late-style bone buttons, one copper thimble, one half of a round blue bead, and seven Chinese coins. Since two of the coins dated to the K’ang Hsi reign period (1662-1772), four dated to Yung Cheng (1723-35), and only one dated to Chia Ch’ing (1796-1820), it was tempting (in the absence of fixed dates on other objects) to place the burial in the first decades of the 19th century.

Coins of the Historic Period

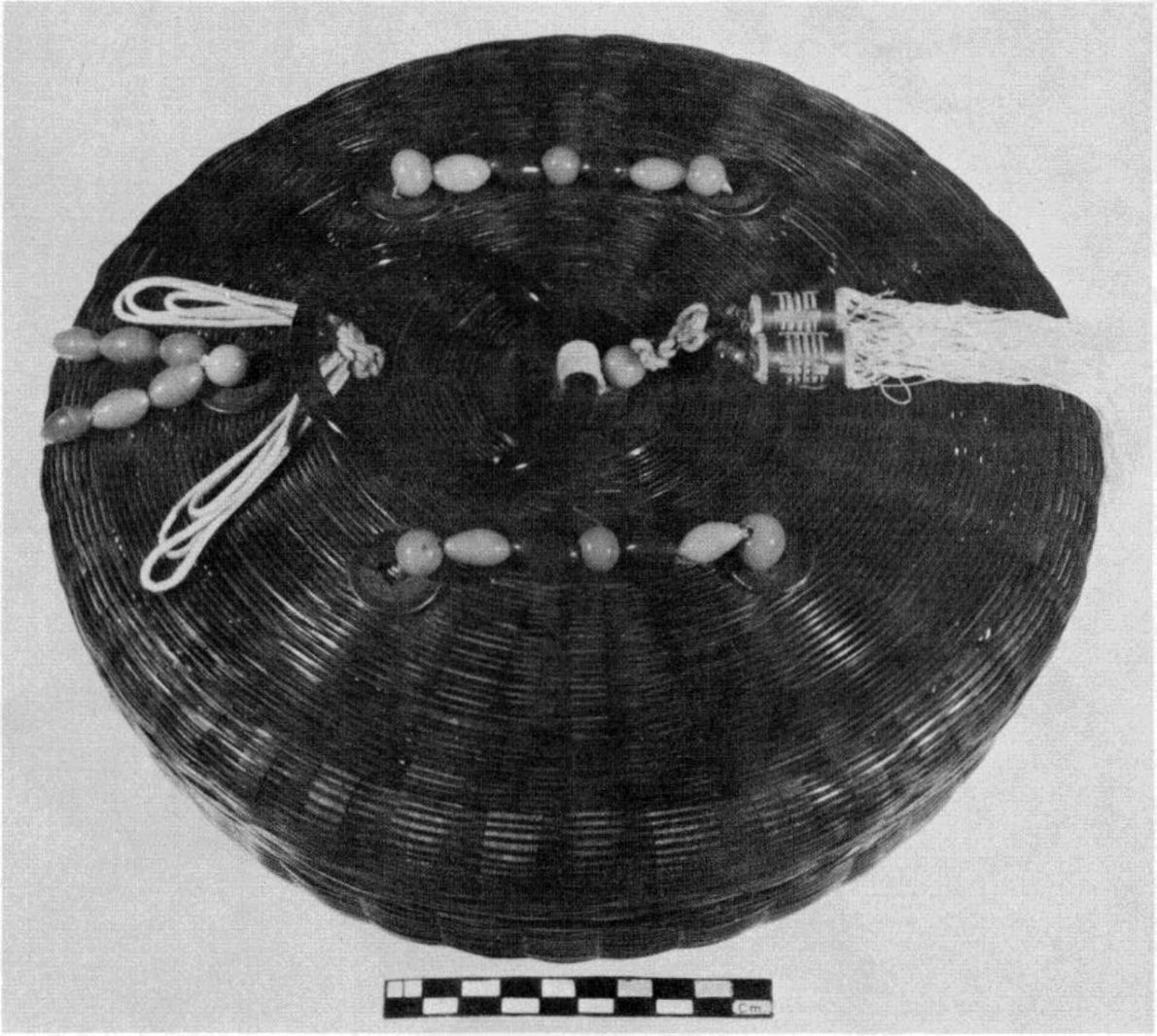

Out of curiosity I examined Chinese coins in museum collections that could be associated with local Chinese populations of the middle 1800’s to early 1900’s. Some of these were loose caches of coins while others were on clothing or part of ceremonial objects. A large number of these coins proved to be from the four oldest Ching Dynasty reign period (1644- 1795), as well as a small number from the previous Ming Dynasty. It was common, even for items dating to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, to be associated with many early dating coins and with few or no coins dating to the period in which the object was made. For example, two Chinese “sewing baskets” decorated with a total of 21 Chinese coins (B.C.P.M. Modern History Division Nos. 971.61, 2078.1, and 971.612- 077.1) of a type that were popular during the early 1900’s, have coins from the following reign periods: Fourteen Ch’ien Lung (1736-95), five Chia Ch’ing (1796-1820), and two Tao Kuang (1821-50). This same pattern of conservatism in circulating old coins appears even today in Victoria coin stores. According to store operators the small numbers of coins they do get filter in mostly from the local Chinese population and are generally not purchased from outside markets.

It is evident that coins circulating in China during the Ming and Ch’ing dynasties represented a considerable variation in manufacturing dates at any one time period. This is probably due in part, as Dr. Charles Borden (pers. comm., 1977) was told by Dr. Ping-Ti Ho, to the known practice of taking coins out of circulation, storing them for long periods of time, and then reintroducing them, as well as the practice, as told to me by the late Dr. Ching-Chang Chuang (pers. comm., 1974), of keeping coins of certain reign periods as tokens of good fortune and passing them on to the next generation at the time of marriage.

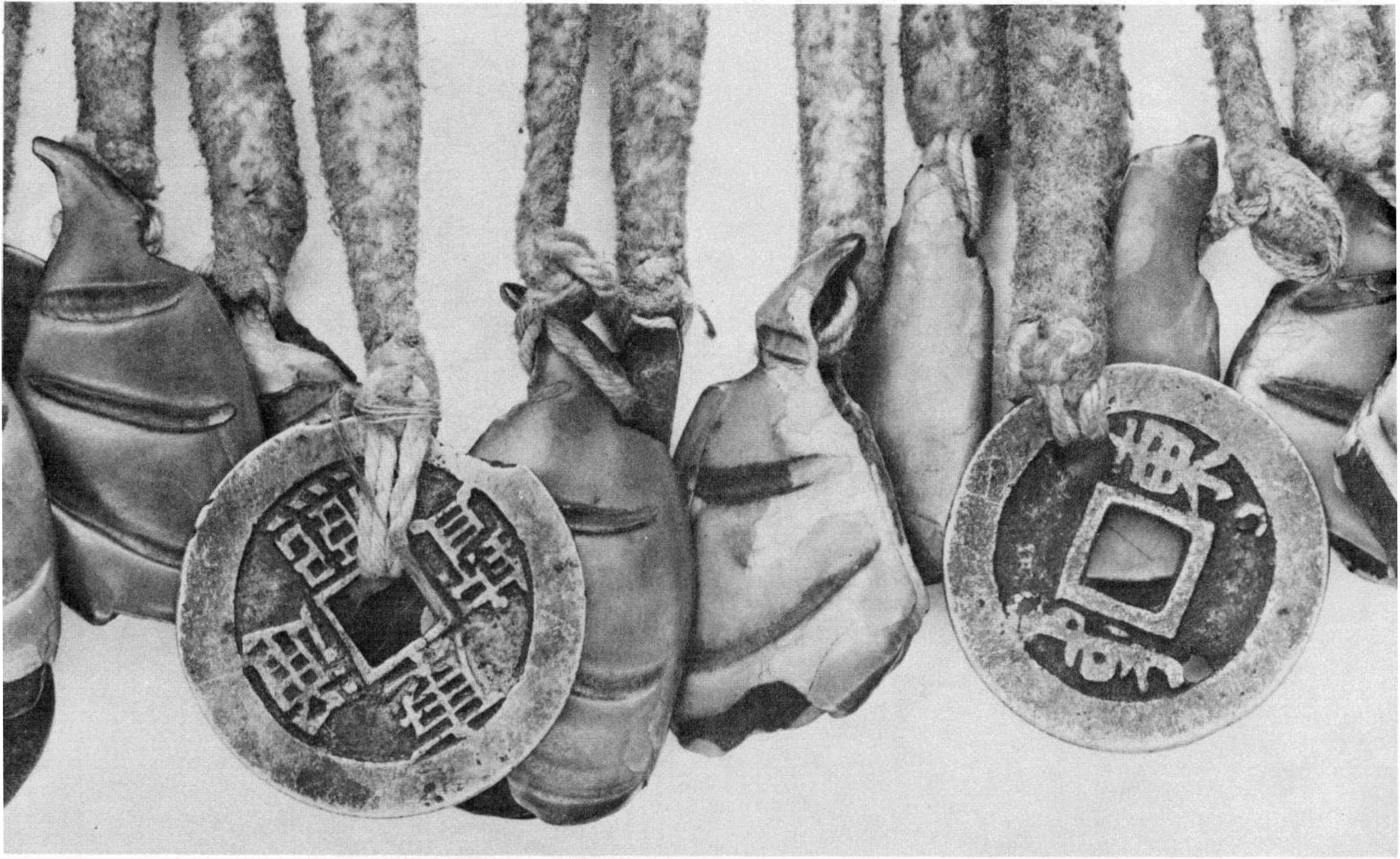

In addition to Chinese conservatism in circulating older coins, one must also take into account Amerindian conservatism. Such conservatism appears to be evident in regard to ethnographic specimens. For example, a Niska Dance apron from Kincolith (B.C.P.M., Ethnology Division, Cat. No. 14293) has a fringe of rawhide strips decorated with 26 Chinese coins (also attached are 25 copper tinklers. 44 ungulate hoofs, and 47 puffin beaks). Nineteen of these are from the K’ang Hsi reign period (1662— 1722), three are from the Yung Cheng period (1723-35), and four from the Ch’ien Lung period (1736-95). It is not known when the apron was made but it is known to have been worn by shaman Frank Bolton in 1928 when performing on a patient at Kincolith. This event was filmed at the time (B.C.P.M. Film Cat. No. TSI-F-007). A dating sequence has not been established for the introduction of the materials (cottoncloth, felt, satin) from which the apron is made, but given their excellent condition it would seem unlikely that the apron was made in the late 18th century as the coin-dating sequence would tend to indicate. Whether the coins had been on several aprons before or not, the point can be made that their dates of manufacture do not reflect the immediate time period in which the item was last used.

Given this apparent conservatism in the age-distribution of a “living” population of coins it would be reasonable to suggest that many of the coins brought to trade with Amerindian peoples in the 1790’s (the most intensive trade period with China) would be of considerable age at the time they were traded. It can be concluded that archaeologists should expect to find early dates on Chinese coins that they find in recent levels of archaeological sites in British Columbia. Coins dating back to the early 18th century can be expected to be common, and it is not unlikely that coins dating as far back as the 11th or 12th century would be found in sites that post-date the mid- 18th century. The earliest Chinese coin found to date in an archaeological context in British Columbia is, in fact, a Sung Dynasty coin dating to circa 1125 a.d. from a late 18th century context at the Chinlac Village site in the Central Interior of the Province (Borden 1952).

References

Borden, C. E, (1952) Results of Archaeological Investigations in Central B.C. Anthropology in B.C. 3:31-43.