Introduction

The Gorge Waterway is a special place in the tradition and economy of the Indigenous Lək̓ʷəŋən people of Greater Victoria. The Gorge reversing falls were the focus a special creation story for the Lək̓ʷəŋən, but also became a special place of celebration for the European populations that infiltrated into their territory.

It is a story of transition between interconnected worlds with a moral that is aimed at bringing about a better world. A theme of preservation that transgresses time.

The legend of this beautiful spot produced the first name “Fort Camosun” used by both the Indigenous Lək̓ʷəŋən peoples and fur traders (see appendix 2). Today it provides the name of Camosun College and Camosun Street.

In the Lək̓ʷəŋən tradition, Camossung was a Spirit Being connected to the area of the reversible falls. At the falls, a little girl named Camossung and her grandfather, Snukaymelt (“diving”), were turned to stone, by a creator/transformer, named Hayls. He had different names, in the various languages, as he travelled along the coast, changing the existing world and creating new features in the world he encountered.

The transformed Camossung stones could be seen under the water facing up the Gorge. Two stone figures were said to rise and fall with the level of the water.

This is a sacred place where people sought spirit powers. On this spirit quest, persons would jump into the water below the falls, holding a rock to take them to the bottom, until Camossung took pity and granted the powers they sought. It was believed that only persons who practised regular spirit-cleaning rituals would gain the powers necessary to acquire success in life. It was believed that garments washed in the foam from the falls protected people from drowning.

In the early nineteenth century, the Lək̓ʷəŋən people were under the constant threat of war raids. They retreated up the Gorge to Portage Inlet in the territory of one of their tribal groups called the Xwsepsum, whose village was once located where the old Craigflower school and the Tillicum school are today. Here, it was believed, Camossung would protect her people from their enemies (Keddie 1992).

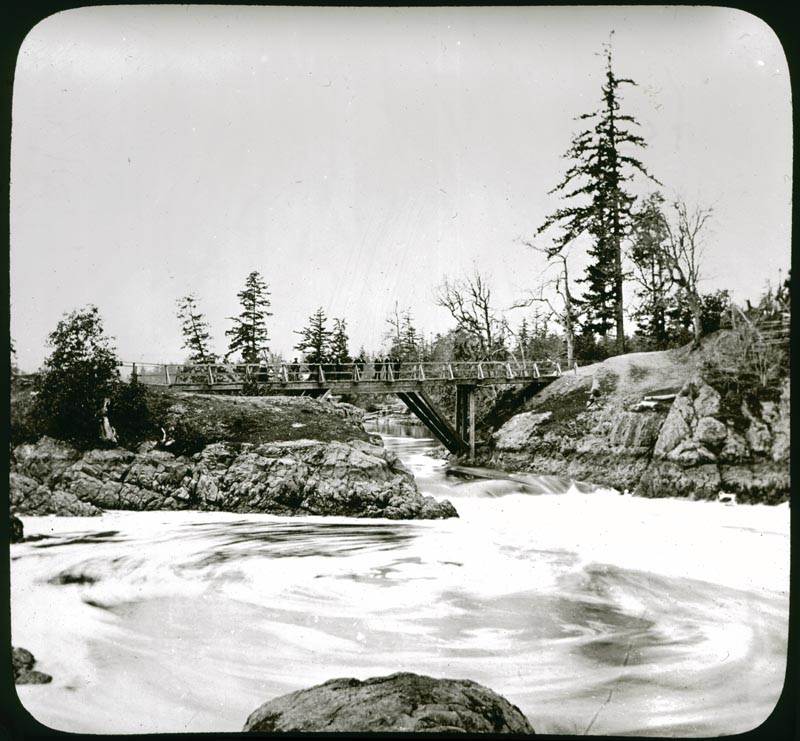

Figure 3, shows the rock of Camossung at the centre of an earlier configuration of the waterfalls at low tide, under the third Gorge Bridge, between 1872-82. It shows the natural foam of the waterway caught in a whirlpool.

Recorded Stories of the Past

We know from many examples of stories recorded around the world, that the interpretation of stories gets altered over time. Sometimes it is a key point in the story and sometimes changes to the names of the characters of the story, that enhance the families of the story tellers.

Biases occur, for example, when people telling a traditional story, and people writing down what has been said, who have been Catholics for five generations, are prone to interpret stories base on the beliefs that they have been exposed to. It is common for Supernatural Creator or transformer Beings to be mistakenly assumed to be the same as the Christian god. This is especially true when the story teller and story recorder do not understand each others language.

Stories that have specific events or plots, such as the European story of Jack in the Bean Stock, or broader stories about events that lead to a row of arrows extending to the sky, are easily past from one culture to another. Indigenous stories from across Canada told during the fur trade period in British Columbia and stories told in Christian churches have filtered into the telling of Indigenous stories.

There were often different versions of stories told by different families. When an anthropologist attempts to record a story in an Indigenous language they are often long, if the teller knowns the whole story. However, newspaper stories written in the past have usually been short and piecemeal, and are written by individuals who have little knowledge of the culture being recorded. Unfortunately, the latter is the only remaining source of many stories. For a very different Indigenous story of Camossung see Appendix 3.

Putting the Camossung Stories Together

The story of the defensive location at Maple Point in the Gorge Waterway was told by Lək̓ʷəŋən born David LaTasse and translated into English during a ceremony at the location on March 30, 1927 (Keddie 1992).

The same year, a written account, mentioning Camossung, was claimed by the author to have been first heard by them in 1887. The newspaper writer, used a pseudonym, Xola-The Chalan. In the article it is not clear where they were getting the information for the story. Another story on “How Deer Came into Being”, in the same article, is attributed to “Mrs. Spenser, a native, of Songhish blood, who resides now at Harty Bay” (Xola 1927).

It is uncertain if the information presented by David LaTasse in the Lək̓ʷəŋən language and interpreted into English at the time was not a source of the information of the reporter “Xola – The Chalan” who records the following:

“Current among the Songhish Indians of forty or fifty years ago [1877-1887] was a tradition which, when told me a year after my arrival [1887], thrilled me. as it was the first aboriginal tradition, I had heard from native lips. Scarcely a remnant of the tradition subsists today, but such as are found substantiate its main tenures.

It is the story of Camosun. the ancient pan god of this tribe. The abode of Camosun was in lake basin lying above the Gorge in and around that placid Inland water now called Portage Inlet, with natural fortification at the Gorge Itself. The legend has it that when the Songish were attacked by hostile tribes from the North they made as gallant and prolonged resistance on the site of their tribal location—the Reserve— as possible, but as this was open to attack from water on three sides, ultimately successful resistance was impracticable.

Power of Taboo. The Songhish, therefore, acting by strategy, moved their entire encampment with all its people into the basin behind the Gorge. Here they were safe, because of a superstitious belief that the Camosun and his satellite gods and goddesses thronged the whole area of rising ground on both sides of the Gorge and made the refugees invulnerable to attack. Their security lay, not in the fact of impregnability of fortress, but because of the safe guarding by Camosun”.

The fortified location mentioned here would be the high mound that was once at the south end of the modern Craigflower school, which was bulldozed away in the 1960s. This was part of a larger archaeological shell midden, site DcRu-4.

The Stories of Jimmy Fraser

Most stories of the recording of the legend of Camossung are those of Lək̓ʷəŋən story teller Jimmy Fraser (Kin-Kay-nun; Unthame, Cheachlacth), born c. 1871 on the old Songhees Reserve (Keddie 2023). Jimmy was the grandson of Chee-al-thluc, or “King Freezy”, the head of a Lək̓ʷəŋən family who was given the title of “chief” by the personnel of the Hudson’s Bay company at the time of the founding of “Fort Camosun”.

A piece of the Camossung story was recorded in 1950, from Jimmy Fraser by anthropologist Wilson Duff as follows:

“After the Flood when Raven, Mink and the Transformer Hayls were travelling around teaching the people how things were to be done, they came to this place, and found a young girl and her grandfather. The girl, Camossung, was sitting in the water, crying. ‘Why are you crying?’ asked Hayls. ‘My father is angry with me, and won’t give me anything to eat.’ ‘What would you like?’ he asked. ‘Sturgeon?’ ‘No.’ ‘Berries?’ ‘No.’ She refused a lot of things, and that is why they are not found along the Gorge. ‘Duck? Herrings? Coho? Oysters?’ These she accepted, and that is why they are plentiful here. ‘You will control all of these things for your people,’ said Hayls. Then he turned her into stone sitting there under the water, looking up the narrows. Her grandfather’s name was Snukaymelt (snek’c’melt) ‘diving’. Since she liked her grandfather to be with her, he was also turned to stone, as if jumping in carrying a rock to take him to the bottom. The two figures, he said, are just below the bridge and rise and fall with the level of the water, staying just beneath the surface.

The Gorge has captured the imagination of all who have seen it. To the Indians it was a sacred place. On spirit quests they would jump in here, holding a rock to take them to the bottom, until Camossung took pity and granted them the powers they were seeking” (Duff 1969).

Five years later in a newspaper interview, Jimmy Fraser is paraphrased as saying: “Camosun, with the welfare of her people in mind, asked Kalis for trees which would ‘clutch the sky’, flowers to cover the rocks, a good harbour to protect the canoes of the tribe and for milder and warmer winds.

Kalis promptly changed some of her people into trees known today as Garry Oaks. He transformed others into flowers, such as blue camas and the Easter Lily, and bade the northwest wind warrior spirit not to deal too harshly with the land of Camosun. He made the harbour and the Gorge inland waterway next.

Indian women believed garments washed in the foam from the falls protected them from drowning. As they worked, they crooned a mournful tribal chant to appease the god of water…. Superstition among them was that if a man was sick, when the water was flowing inland, he would recover. But if the current was seaward, he would die.” (Smith 1955).

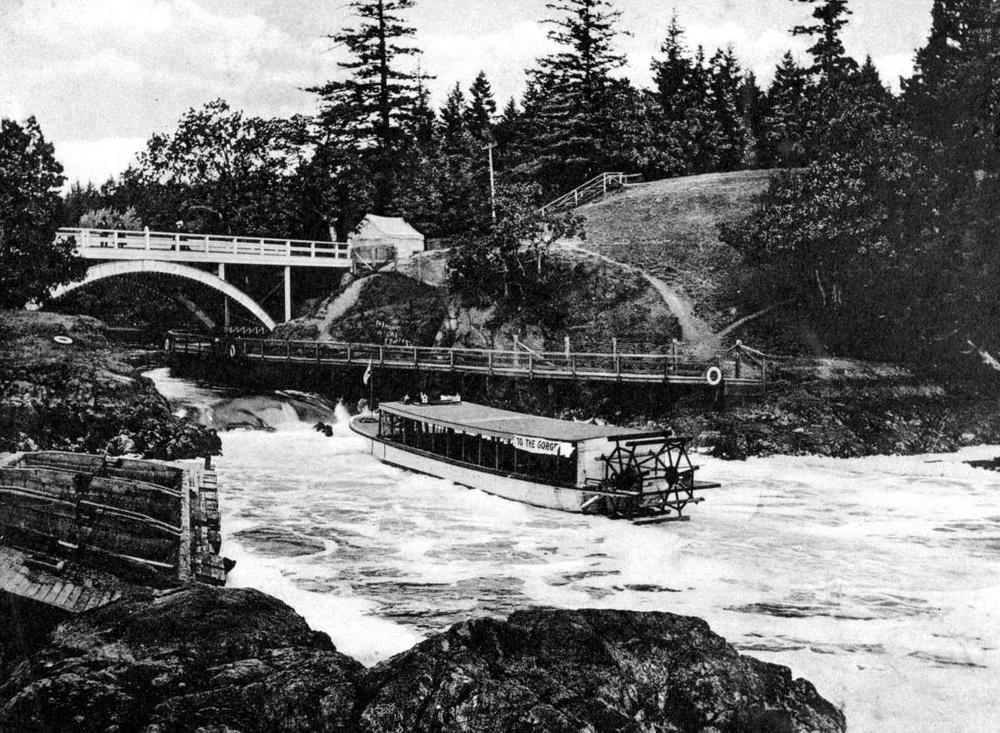

Figure 4, shows Camossung Rock to the left of centre under the fourth Gorge Bridge at low tide. The configuration of the water flow on the right side is different now because this is where rock was removed in 1960.

The same year, in another interview, by Judy Graham, for an article in the Daily Colonist, was entitled: The Songhees God was Angered. Under the Old Gorge Bridge Are Rocks with a Strange Legend. The use of the term “god” here is not the same as the Christian God. The spirit being Hayls, is one who came into an existing world in the distant past, in various human disguises. He changed humans into animals and plants and re-modelled landscapes. He is more appropriately considered a creator/transformer being. The anglicized spelling of the name Camossung, preferred by linguists, is different in this article. She wrote:

“Jimmy Fraser, 86, the oldest full blooded Songhess left in the tribe, is perhaps the only person who knows the legend of the young girl who was too greedy.

Karmossen was the girl’s name and she lived with her grandfather on a site near the old Craigflower school. A flood came and destroyed their home site and left them starving. They wandered along the banks of the Gorge looking for food but could find none. Karmossen pleaded to the Songhees god, the sun, to provide her with food, and the kindly god responded to her pleadings.

The god leaned down and offered sturgeon. The girl said she did not like fish, so the god gave it a mighty heave and it landed somewhere on the mainland. Then the god offered cranberries and again she refused, so the god threw them to an area around Shawnigan Lake. The girl did not want the preferred oysters, crab or duck. In fact, the god decided, she wanted too much. Karmossen received punishment for her greed where she stood. the god took, with her grandfather beside her, a handful of water from the Gorge, sprinkled it on Karmossen, turning her to stone. Her grandfather standing too close to her, was also turned to stone.

Anyone who swims near the Gorge Bridge or has taken a boat under it at low tide is familiar with the two large rocks forming the narrow passage.

According to Jimmy Fraser, the head of the grandfather was removed during the construction of the present Gorge Bridge. The wise man of the tribe said two men died because they touched the grandfathers head while paddling their boats through the passage in the early days.

Karmossen was angered when the men struck her aged grandfather and created dangerous whirlpools which turned the boats over, drowning the men. That is the reason there are whirlpools there still.

Jimmy Fraser says that the Gorge area, once abounded in crabs, herring, duck and oysters before the white men moved in.

The Songhees god who offered Karmossen this bounty did not approve of the white men and took away his gifts, leaving little in the Gorge for the white settlers.” See Appendix 1 for a discussion on the Camossung Rocks.

Figure 5, shows the fifth Gorge Bridge falls during low tide in 1908. The Camossung Rock appears like two rocks in this image.

Appendix 1. The Rocks of Camossung

What Happened to the Rocks of Camossung

What is important in the description that Jimmy Fraser gave to Duff is that:

“The two figures, he said, are just below the bridge and rise and fall with the level of the water, staying just beneath the surface”.

I have observed on a number of occasions, what I considered the Camossung Rock, when below the surface, just east of the main part of the falls. Due to the force of the water during the tide change there is an illusion that gives the appearance that the Rock is moving up and down under water, like they are alive. I would suggest that this is what Jimmy Fraser was referring to in talking about the “rise and fall” of the Rock. This is inline with the beliefs of Jimmy Fraser that the rocks had special spirit power and could communicate with humans. Jimmy was “famous as a mystic” who could “talk to animals” and “forces of nature, including the spirit world” (Province 1953; Davy 1953; 1955; 1957; 1967; Loughman 1953; Newton 1950).

Jimmy Fraser is quoted as saying: “the head of the grandfather was removed during construction of the present Gorge bridge”. The bridge of that time was built in October 1934. There is no mention of this incident at the time. Graham’s (1955) paraphrasing from Fraser explaining that “two men died because they touched the grandfather’s head while paddling their boats through the passage in earlier days”, may pertain to historic deaths that occurred. We know that there are reports of two people dying after striking the rocks not too long before this interview. It may be that it was this incident that was referred to by Jimmy Fraser.

The late Chief John Albany, told me in 1974, that Jimmy Fraser was often confused in his old age about events of the past. When reporter Barry Johnston interviewed Fraser in an old age home in 1963, he observed that:

“He is nearly deaf and often now speaks indistinctly, and more often than before slips into abstract terms of lament about the white man and the loss of the coho and sockeye and destruction of Indian medicine by bull dozers crushing the spirit stones”.

Figure 6, shows the pre-1960 water flow as seen on this oldest photograph of the Gorge Falls. The rocks removed in 1960, are those on the far right. The Camossung Rock is just below the falls. Where the falls are turning down on the north side, one can see rocks that are influencing the direction of the water.

This can also be seen in the same location in figure 4. The Camossung rock can be seen as a slight dark streak just forward of the falls, just below the surface.

Rock Removal in 1960

Rocks were removed by drilling and dynamiting in 1960, but it is my opinion that these were not the rock figures representing Camossung. The stones of the cultural tradition are those still visible today at low water.

When the tide changed and the water above the bridge flowed downstream it is the rocks forward of the main falls area that were hiding and a danger to canoes breaking on them, because they often could not be easily seen when traveling from west to east. I discovered this by my own canoe experience. The extent to which these rocks are visible has changed since the opening of the flow on the north side of the falls.

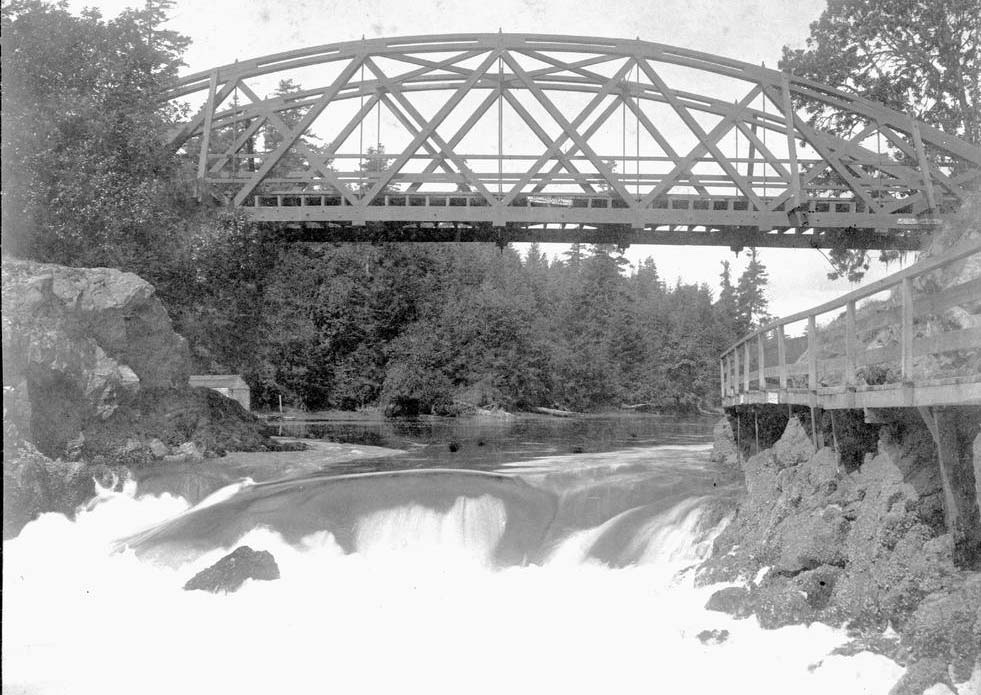

Figure 7, shows the high flow across the falls under the fourth bridge in 1895. The left side in the image turned down toward the north when the chunk of rock was removed in 1960. The Camossung Rock, forward of the falls, can be seen just emerging from the surface.

On June 14, 1960, the Victoria Daily Colonist produced an article “Gorge Bridge Blasted for Rocks”:

“A pinnacle of rock which prevented large boats entering the Gorge past the Gorge bridge was blasted into a hole in the bed of the waterway Sunday. The privately financed operation has made safe a channel some 2 1/2 feet deep on the east side of the Gorge which will float boats up to 30 feet in length.

Robert Southwell, operator of the Gorge Boathouse, paid for the work. An attempt to drill into the pinnacle of rock Saturday failed when workers and equipment were tipped into the water from a raft by the tide current. The drilling was successfully completed Sunday afternoon from a 33-foot cruiser, owned by Jack Lord.

The demolition of the rock came too late to save a boat which was badly damaged by the hidden pinnacle of rock Saturday. The pinnacle was part of the huge rock which formed a natural dam for the northern part of the Gorge waterway. The blast toppled the pinnacle into a 20-feet-deep hole beside the rock dam”.

A Victoria Times article of June 13, 1960 (page 15) indicated that the people that did the drilling and blasting included Jack Lord and Jim Gillespie. On June 12, they dynamited off a 76 cm (c. 26 inches) chunk of rock. In the 1970s I talked to two people who observed the rock removal in 1960. They said the rock piece removed was on the northern part of the falls, which opened the channel on the north side. This allowed people to pull boats through that side by walking along the raised walkway. Small boats, canoes and kayaks coming from the west could pass through the north side at high water and avoid hitting the rock near the middle.

Appendix 2.

Camossung. Naming in 1843.

A letter of April 14, 1843, from John McLoughlin to Archibald McKinlay of the Hudson’s Bay Company, refers to the fort area as “named Camoosan, by the natives, and which we have named Fort Victoria as the Council directs.” (McLoughlin’s Fort Vancouver letters, First Series, Vol. 1:136; add. Mss. 1917).

The log of the Hudson’s Bay Company ship Cadboro begins on June 25, 1843. The entry for July 4 mentions Charles Ross as being “In Charge of Cammoosan”. The next entry notes, in “Charge of Camosun” as well as to three “men from Fort Camosun” assisting in discharging cargo. The July 29 entry records outfits being taken out of the ship Columbia for “Camosun, Langley & Nisqually”. Aug.6 “proceeded for Camosun”. “Noon anchored in Camosun Harbour abreast of Fort Albert..”. [several refs. to Fort Albert after this]. last ref. as “Camosun” Sept. 24, 1843. Entry – Nov. 27 “Towards Fort Albert”. Dec. 4, last ref. to “Fort Albert”. Dec. 12-18 entry “At Fort Victoria Camosun Harbour”. Jan 16, 1844 “Fort Victoria”. (RBCM Archives C.1/221)

Roderick Finlayson in a letter to Bancroft of Oct. 18, 1879: “Songheis is the name of the Tribe of Indians here, when Fort Victoria was founded” …“place first named ‘Camosun’ that being its Indian name, taken from the rush of natives {waters} at the Gorge.”. (in History of Vancouver Island and the North West Coast, A/B/30/F49.1). Also see Biography of Roderick Finlayson. (Archives of B.C. NW 971.1vi F 512)

In 1837, Capt. McNeil in the steamer Beaver, visited the harbour which the Lək̓ʷəŋən called “Camosun or ‘The place of Rushing Water’. [Not the literal translation]. “In a letter to Governor Simpson, Capt. McNeil described Camosun as very suitable for such an establishment as Fort Vancouver, except that there did not seem to be water enough to turn mills.”. (Editor. J.H.S. Matson. Victoria City and the Island of Vancouver. Story of the Founding of Fort Victoria by Officers of the Hudson’s Bay Company – Some interesting Historical Data. The Daily Colonist. 1908. March 8:21).

Appendix 3. Another Story of Camosun.

In a newspaper article of July 14, 1911, reporter C.L. Armstrong, received a story from a Songhees ”old” man while sitting in front of the Old Songhees Reserve in Victoria Harbour, just before the Songhees moved to the New Reserve on Esquimalt Harbour. This story implied that the name Camosun referred to sea creatures that lived under the Gorge waterfalls. The story tellers English name was not provided. He was referred to as: “Fish-Tail, the son of Many Tongues”.

“Fish-Tail turned slowly to the white man who was his friend. Perhaps it was the mood induced by his reverie that made him open his heart; perhaps it was the realization of the close of an epoch. After a pause he swung his arm slowly toward the city where the tall white street lights now shone brilliantly. “You white men,” he said, in fluent English, “call Victoria Camosun because the old fort of the King George Men …was called Camosun. It is wrong. I will tell you a true story”:

“Have you ever noticed the masses of white foam that sometimes drift down the harbour from the narrow place above? It comes from what you call The Gorge. Well, that foam was made by the Camosun. They are animals formed like huge fish and they live in the sea. Their home is at the bottom of that narrow place you call The Gorge. Many years ago, there were great numbers of these, but they are few now. I know that by the small patches of foam that drift down when the tide ebbs. Once, the whole harbour was covered with the froth; now there is very little and I know the Camosun are passing away. In the old days the roaring they made when the waters rushed swiftly through the little passage was fearful and made men draw back: now one can scarcely hear them.

“It was the Camosun that used to guard the narrow place and the shores above where the banks were covered with the lodges of our tribe. Over there where your great town is now no one lived. There we hunted and the hunting was good. Our young men made nets of rawhide and snared the deer and the elk on the grounds where Senator Macdonald now has his home. The young men stretched the nets between two leaning poles across the runways of the foolish deer. The deer ran against the net and the poles fell, tangling the unwary victims so that the hunters killed them easily”.

“Yes, it was thus that the Camosun guarded The Gorge and they guarded it well. Who was there of all the tribe in those days who could dare to face the narrow place in a canoe? One day when almost all of our men were away hunting and fishing, a war party of enemies stole up the arm from the sea. They hid themselves below our village and waited until darkness came. Then they manned their war canoes and paddled almost to The Gorge and waited there until the new sun began to streak the east. The waters were as a sheet of glass, for the Camosun slept. The invaders paddled quietly through and stopped below our village. They kept close in the shadows of the dark woods and waited, for no smoke arose from the lodges. After a time. our women appeared, fetching water and firewood. Columns of blue smoke rose from the lodges and there was a noise of a new day in the village. And yet the invaders remained hidden. Soon our young women were setting about the day’s work, some going for the night’s wood, some for roots and herbs, others for oysters, of which there were great quantities in those days. These oysters, in fact, were the food of the Camosun. Soon a party of girls were working along the banks, gathering the camas in baskets. They sang as they worked. They thought of the young men who were afar at the fishing and hunting. They had no thought of danger; but as they worked, they drew nearer and nearer the canoes hidden in the shore bushes. Suddenly there was a rush of feet, and a quick, sharp scuffle, and the maidens were born swiftly to the canoes.

“Out from the lodges ran the crippled old men, the women, and the children. No young man was there to raise a hand in defense; there was none who could pursue. Those on the bank wrung their hands and raised a wail for the young women who were now destined for slavery. But wait! – the triumphant cowards approach The Gorge in their swift flight. The waters are no longer still. What is this? They leap and swirl and twist and turn. The roaring is as a thousand thunders in one. The Camosun are awake and rushing to defend their passage. On rushes the long war canoe with the captive girls and the enemies of our people. The Camosun leap into the air and lash the waters into an awful fury. The canoe, drawn by unseen arms, moves faster and faster, now it is in the mad waters and the Camosun, spring high and dash themselves against its sides.

The strong, seasoned wood crumples beneath the impact like paper. Now the end comes; the boat is split from bow to stern and captives and captors struggle in the white foam. The men quickly disappear, pulled to the depths by the fierce Camosuns. But the women are floated gently ashore, unharmed and they quickly run to the village and tell the news of their wonderful deliverance.

“That my friend is the story of the Camosun and the Land of the Camosun. There are no oysters for the Camosuns’ food any more. The white men have taken them all and the white men have frightened the Camosun away with the puff boats and much noise. The village is gone from the banks above and the white men go there in electric cars and make it a playground. Moreover, they have built a bridge across the Camosuns’ passage and the Camosun are needed no more. Therefore, they have gone away. A few still remain, but they are never seen now, but that is the story of the Land of the Camosun. Many years ago, when Governor Douglas and The Company came, they heard of the land of the Camosun and they thought it meant all the land around here. Therefore, they built a fort and called it Fort Camosun, and then, when the fort was gone, the white men built a great village and called it Victoria. But sometimes, even now, they call it Camosun. That is wrong” (Armstrong 1911).

References

Armstrong, C. L. 1911. A Camosun Story. Victoria Times July 14. From Colliers Weekly.

Daily Colonist. 1908. Victoria City and the Island of Vancouver. Story of the Founding of Fort Victoria by Officers of the Hudson’s Bay Company – Some Interesting Historical Data. The Daily Colonist. March 8, 1908.

Daily Colonist. 1960. Gorge Bridge Blasted for Rocks. The Daily Colonist. June 14:17.

Daily Colonist. 1960. Indians’ Hands Full Fighting Hard Winter. December 22.

Davey, Hunphrey. 1953. Weather Wise. Times Newspaper, January 24.

Davey, Hunphrey. 1955. Ancient Songhees Tribe Sagas Tape-Recorded by Old Indian. Preserved for Posterity. Times Newspaper, June 3:13.

Davey, Hunphrey. 1965. Snow Go, Sun Come Pledges A-Hoo-La. Times Newspaper , Jan. 9:21

Davey, Hunphrey. 1967. A-Hoo-La, Friends Mourn Gentle Jimmy. Gone to Spirit Land. Times Newspaper, December 1:11.

Duff, Wilson. 1969. The Fort Victoria Treaties. B.C. Studies No. 3:3-57.

Graham, Judy. 1955. The Songhees God was Angered. Under the Old Gorge Bridge Are Rocks With a Strange Legend. Johnston, Barry. 1963. Snow, Wind, Not Coming. The Daily Colonist. November 30, 1963.

Keddie, Grant. 1991. The Legend of Camosun. Discovery: Friends of the Royal British Columbia Museum Quarterly Review, 4(5). https://grantkeddie.com/2023/02/18/the-legend-of-camosun-2/. Also, at grantkeddie.com

Keddie, Grant. 1992. Installation of a Songhees Chief. Discovery. Newsletter of the Royal B C. Museum, 20 (1).

Keddie, Grant. 2003. Songhees Pictorial. A History of the Songhees People as Seen by Outsiders, 1790-1912. Royal B.C. Museum.

Loughnan, Brian. 1953. Indian Sign Put on Weather. The Daily Colonist, January 4.

Newton, Betty C. 1950. Notes on Jimmy Fraser. Deposited with the Archives April 12, 1950.

Newton, Betty C. c.1950). Written Straits: A story told to Betty Newton by James Fraser Unthame Cheachlacht, Songhees Indian. RBCM Archives File GR-2809.54.

Smith, Edgar. 1955. Magic Foam. The Vancouver Sun. October 22, 1955.

Xola – The Chalcan. 1927. Songhees Tell Camosun Story. Tribes Moved to Reserve behind Gorge because Gods and goddesses guarded them there. The Daily Colonist, Oct. 2, 1927, p. 5.