By Grant Keddie,

The legend of the Dragon’s Hole on Kinnoull Hill outside Perth, is about dragons, magic stones, Beltane rituals, Christian appropriation, an echoing hollow, the Scottish hero Wallace’s hide out, Saints and one of my prankster ancestors James Keddie. Through his actions around 1600, James Keddie, a tailor living in Perth, managed to wedge himself into the story. The legend has become a blend of different versions from different times. Changes in names and places in stories take a different focus for new story tellers, as I do here by providing more of a highlight on one of my ancestors and their role in this convoluted story of the Dragon’s Hole.

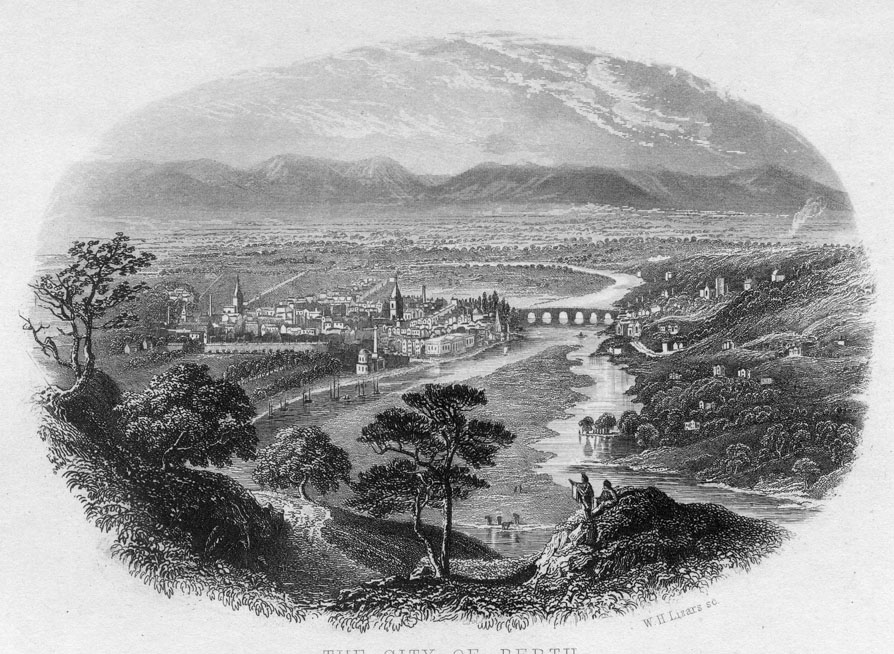

The Setting

The scene of the dragon’s hole and the stories about it are on Kinnoull Hill, a municipal park just outside Perth, in S.E. Perthshire. The wooded top of Kinnoull Hill is above the steep basaltic cliffs over 200 meters above the River Tay below.

Francis Groome, the editor of Scotland’s Ordnance Gazetteer for 1883, provides an overview of Kinnoull Hill:

“From Perth its summit is gained by a winding carriage-road, called Montagu’s walk after the Duke of Montagu, who was in Scotland when it was formed; and that summit commands a magnificent prospect, by Pennant entitled ‘the glory of Scotland’. Near the Windy Goul, a steep and hollow descent betwixt two tops of the hill, is nine-times-repeating echo, and on the hill-face is the Dragon Hole, a cave where Wallace is said to have lain concealed, and where Beltane fires formerly were kindled. The base of the hill has yielded many fine agates; and a diamond is said to have gleamed from its cliffs by night, till a marks-man, firing at it with a ball of chalk, was able next day to find its whereabouts – a tale that is told of a dozen other localities” (Groome, 1883:407).

The Beltane fires refer to the important celebration feast of the start of summer on May 1st, when great bonfires were lit on prominent hilltops across the country. The annual Festival of the Dragon was celebrated on Beltane in honour of St. Serf.

In the 6th century, a dragon was terrorizing the region from its lair overlooking the river. Help came from a Christian monk, St. Serf, who slew the dragon. In recognition of this event the local people started the annual Festival of the Dragon. The dragon of Kinnoull was believed to have had a large diamond-like stone in the middle of its forehead – the source of its power and a highly valued treasure of magical powers, such as giving the power of invisibility to anyone that possessed it.

What are the magic or enchanted stones?

In Scotland adder stones or snake stones were used as protection against snakes or cures for snake bit and a number of diseases. These semi precious stones included crystals, agates or fossils that had the appearance of a snake (Halliday 1924).

Richard Pococke in his visit to the Dragon’s Hole in 1760, refers to these stones: “We returned back opposite to the town, which lies in the parish of Kinoul,…We went on and came to the hills of Kinoul, that abound in Agates and Chrystall, the latter enclosed in hollow stones which fall from these fine high rocks that are opposite to Elcow. We saw Elchow house on the other side, built high in the Castle manner”. (Kemp 1887:259).

A geological explanation of the stones is given in 1784, by De Saint Fond, who came to Kinnoul Hill to collect rocks. The cliff area was “richest in agates”. He describes these in his numbered rock collection: “13. A geode of agate, internally lined with brilliant crystals of violet-coloured quartz, with hexagonal pyramids, enclosed in compact porphyric lava, dark-brown inclining to violet, with some kernels of white calcareous spar, and globules of agate and green steatite. 14. A geode of bright red agate, having in its interior a brilliant crystallization of white quartz of the greatest purity. This geode lies in a black porphyric magnetic lava. 15. Oculated agate of a delicate rose colour, surrounded with dark-brown compact porphyric lava, intermixed with globules of green steatite”. (De Saint Fond 1907:187-192)

What Happened in the Cave?

Samuel J.P. Cowan provided an overview of The Story of the Dragon Hole, in 1904:

“In early times the Dragon Hole was a factor in the social life of the people as a resort on various occasions and for various purposes. It is a cave in the rock on Kinnoull Hill, facing the Dundee Road. It was the scene of annual processions of young people on 1st May, a practice which evidently originated in Druid times, connected with Beltane or Bel-fire, the worship of the Sun. The rejoicings continued to be observed in various forms in early Christian times, and the Dragon Hole was known as such from the most remote antiquity. It is extremely difficult of access, is about 10 feet high, and will accommodate a dozen persons. It is said Sir William Wallace frequented it, and hid in it during his military manoeuvres around Perth. Adamson mentions a certain James Keddie, who found in the Dragon Hole a stone which had the power of rendering its possessor invisible. Keddie lost the stone, and though he often searched for it, it was ever afterwards invisible to him. In the Kirk Session Records of 1580 there is the following entry: “Ordain an act to be made by the minister concerning the discharging of all persons passing to the Dragon Hole superstitiously, and the same to be published from the pulpit and thereafter given to the magistrates and proclaimed at the Mercat Cross.” The act was as follows: “Because the assembly of ministers and elders understand that the resort to the Dragon Hole by young men and women with their piping and drums going through the town has caused no small slander to the congregation, not without suspicion of improprieties following thereon, the assembly with consent of the magistrates have ordained that neither man nor woman resort to the Dragon Hole as they have done hitherto on 1st May under a penalty of twenty shillings Scots for each person found guilty, and that they make their repentance on Sunday in presence of the people.”

Cowan mentions the work of the Scottish poet and historian Henry Adamson who produced some poetic notes on his visit to the Dragon’s Hole, published the year after his death in 1638. Unlike others, Cowan did not misinterpret the story. One passage has been misinterpreted by some that James Keddie found a magic ring, when in fact Adamson says a stone “like” Gyes ring.

Adamson climbed up to the Dragon’s hole and also visited the rock where he could hear his echo. The mention of going with Hay, would refer to Sir George Hay who inherited the title of Earl of Kinnoul, Viscount Dupplin in 1633:

With Hay the day now dawnes, then up I got,

And did advance my voice to Elaes note,

I did so sweetlie flat and sharply sing,

While I made all the rocks with Echoes ring.

Meane while our boat, by Freertown hole doth slide,

Our course not stopped with the flowing tide,

We ned nor card, nor crostaffe for our Pole,

But from thence landing clam the Dragon hole,

With crampets on our feet, and clubs in hand,

Where its recorded Jamie Keddie fand

A stone inchanted, like to Gyges ring,

Which made him disappear, a wondrous thing,

If it had been his hap to have retaind it,

But loosing it, againe could never finde it:

VVithin this cove ofttimes did we repose

As being sundred from the citie woes.

From thence we, passing by the Windie gowle,

Did make the hollow rocks with echoes yowle;

And all alongst the mountains of Kinnoule,

The short and popularized version in Sir Walter Scott’s The Fair Maid of Perth broaches this subject and makes the mistake of referring to a ring instead of magic stone: “What”, he continued, in a jocose tone, “thoughtst thou hadst Jamie Keddie’s ring, and couldst walk invisible? But not so, my fairy of the dawning. I there is a tradition that one Keddie, a tailor, found in ancient days a ring, possessing the properties of that of Gyges, in a cavern of the romantic hill of Kinnoul, near Perth” (Scott 1828:87).

References

Adamson, Henry. 1638. The muses threnodie, or, mirthfull mournings, on the death of Master Gall Containing varietie of pleasant poëticall descriptions, morall instructions, historiall narrations, and divine observations, with the most remarkable antiquities of Scotland, especially at Perth. Printed by George Anderson, King James College, Edinburgh.

Blackwood, William. 1844. Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 56, Number 347, September, 1844, EDINBURGH: WILLIAM BLACKWOOD AND SONS, 45, GEORGE STREET; AND 22, PALL-MALL, LONDON.

Cowan, Samuel J.P. 1904. Perth, the Ancient Capital of Scotland. The Story of Perth from the Invasion of Agricola to the Passing of the Reform Bill in 2 volumes. The story of the Dragon Hole from chapter III.

De Saint Fond, B. Faujas. 1907. A Journey Through England and Scotland to the Hebrides in 1784. Revised Edition of the English Translation. Edited with Notes and a Memoir of the Author by Sir Archibald Geikie. Volume Two. Hugh Hopkins, Glasgow.

Groome, Francis H. (editor), 1883. Ordnance Gazetteer of Scotland: A Survey of Scottish Topography, Statistical, Biographical, and Historical, Vol. IV, Thomas C. Jack, Grange Publishing Works, Edinburgh.

Halliday, W.R. 1924. Folklore Studies. Ancient and Modern. Methuen & C. Ltd. London.

McHardy, Stuart. 2012. Kinnoull Hill, a diamond, and the cloak of invisibility. Strange Secrets of Ancient Scotland. Electric Scotland.

Kemp, Daniel William. 1887. Tours In Scotland 1747, 1750, 1760 By Richard Pococke. Bishop of Meath.(edited with a Biographical Sketch of the Author).From the Original Ms. and Drawings in the British Museum. Edinburgh. University Press by T. and A. Constable, for the Scottish Historical Society. Pp.375.

Pocock’s Tours in Scotland. Publication of the Scottish History Society. Volume 1. October 1887.

Scott, Walter.1828. The Fair Maid of Perth. Perthshire Sayings. Chronicles of the Canongate, Second Series. Cadell and Co., Edinburgh.