Originally published in Perspectives on the Archaeology of Pipes, Tobacco and other Smoke Plants in the Ancient Americas. Interdisciplinary Contributions to Archaeology. Springer, Cham.

2016.

By Grant Keddie

9.1 Introduction

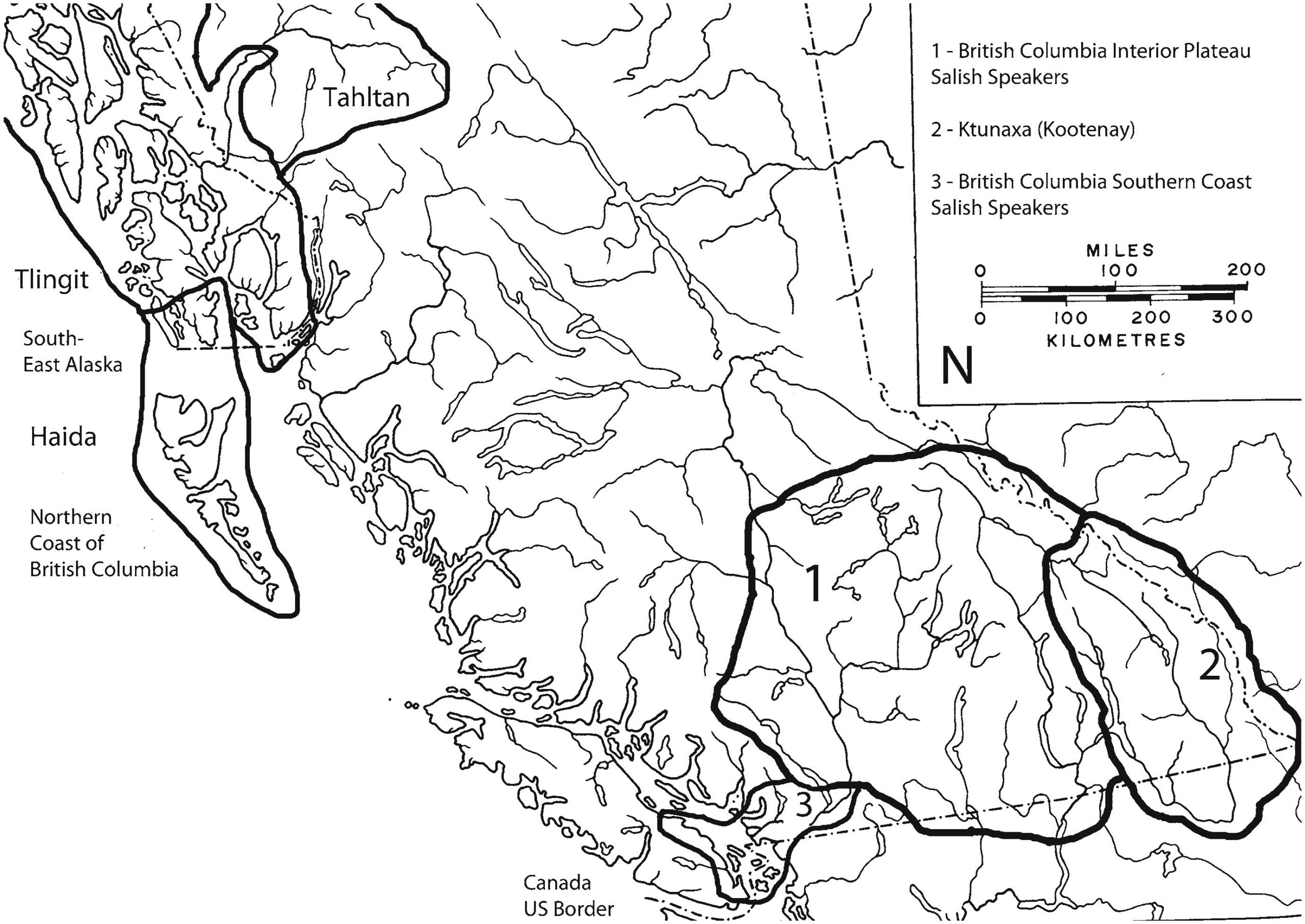

Aboriginal groups in the far northwest of North America were some of most northerly Native peoples throughout the Americas to use tobacco (Turner and Taylor 1972). This chapter provides an overview of tobacco consumption and smoking practices of Native peoples living in British Columbia, Canada, and the Northwest Coast of the United States. The discussion breaks the larger region into three subregions— the Interior Plateau of southern British Columbia, the Northern Coast of Alaska and British Columbia, and the Southern Coast of British Columbia—to compare and contrast the uses of tobacco and pipes between different groups (Fig. 9.1). The main focus of the chapter is on British Columbia, a province that has a diverse range of environments in its 360,000 square miles. Environmental variability can be substantial; the Southern Interior is marked by dry summers and cold winters while the Pacific coastal rainforest has mild winters and is more temperate overall. It was home to Native peoples speaking 32 mutually unintelligible languages belonging to seven different language families. Native peoples throughout the region were hunter-gatherer-fishers, each with their own distinct histories and way of life.

In the Interior Plateau of southern British Columbia, First Nations peoples cultivated or collected the wild Nicotiana attenuata species. The practice of smoking likely goes back to the thirteenth century when stone pipes appeared in the region. Smoking of tobacco does not seem to have been practiced on the coast of British Columbia, southeastern Alaska or among the Dene (Athapaskan) speakers of Northern British Columbia until Europeans introduced it. The Haida and Tlingit

peoples on the northern coast cultivated the Nicotiana quadrivalvis (bigelovii variety) but did not smoke it. Instead, they mixed it with a lime solution and sucked it, a practice similar to that of other cultures far to the south (Barrett and Gifford 1933, p. 195; Heizer and Whipple 1960, p. 24; Kroeber 1941). On the southern coast of British Columbia, the presence of some limited pre-contact smoking practices related to ritual activities is of a speculative nature. The archaeological evidence of mostly fragmentary stone pipes suggests their use as exotic trade items rather than necessarily reflecting evidence of smoking activities.

9.2 The Canadian Interior Plateau

9.2.1 Tobacco

Nicotiana attenuata, a species of tobacco that grows wild in dry areas of the Great Basin, southern Plains, northern Idaho, Montana and Washington State, extended from the south into the dry southern Interior Plateau of British Columbia, where it was both gathered wild and cultivated in small gardens. Its historic use is well documented for the southern Interior. However, European tobacco had mostly replaced it by 1900 (Teit 1900, p. 300). It is now extremely rare in southern British Columbia and has disappeared from many areas of Washington State. This plant was both cultivated and collected in the wild by the Ktunaxa of the Kootenay Region and the Nlaka’pamux (Thompson) of the lower Thompson/Fraser River Region. The area near the Canada-United States boundary became known as Tobacco Plains. Other groups speaking Interior Salish languages: the Okanagan, Stl’atl’imx, and the Secwepemc, smoked tobacco, either gathered wild or obtained by trade.

Interior peoples used tobacco for many ritual purposes. The Ktunaxa of southeastern BC were famous for sowing and harvesting tobacco for ceremonial smoking. The origins of some of their ceremonies known in historic times were shared with their neighbours to the south and east. The Ktunaxa have many legends that make reference to the use of tobacco (Turney-High 1974). Large tobacco gardens were divided off for different families or groups of people. There was the recognition of a head grower who was often called the tobacco shaman and whose medicine was believed to keep the crop healthy. The Ktunaxa also had large gatherings with sports events that involved prizes of tobacco (Johnson 1969).

Among the Nlaka’pamux, when a death had taken place in the winter house, it was purified with water infused with tobacco and juniper, and widowers abstained from smoking for half a year. One year after the death a ceremony was held in which the male relatives smoked a large pipe. The pipe was constantly passed around in the direction of the sun. An old man had to fill the pipe as soon as it was empty. Warriors smoked facing towards the sun and souls were believed to be brought back on tobacco smoke (Teit 1900, p. 331-334; 357-359). In the Southern Interior, tobacco grew in the warmer valleys. The leaves were dried, greased, and mixed with bearberry-leaves, and then roasted. In historic times, women smoked equally as much as the men, but traditionally only women who claimed to be strong in medicine smoked (Teit 1900, p. 300).

A variety of additives were used with tobacco, but it is difficult to determine whether these are older traditions or ones adopted in the historic period as a result of the introduction of European trade tobacco. In the late 1890s, Chief Salicte of Nicola Lake said that the Native tobacco was used without any mixtures and the bearberry plant was used with European-introduced tobacco (Smith 1900, p. 429).

The dried leaves of Kinnikinnick or bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi) were widely known to have been mixed with introduced tobacco for smoking (Anderson 1925, p. 102) and may have been smoked alone. Interior peoples also used Canby’s Lovage (Ligusticum canbyi) with tobacco to give a pleasant taste and provide a relaxant. It was also held in the mouth as a chewing tobacco. Indian Celery ( Lobatium nudicaule) was used as flavouring (Turner 1997, p. 80). Turner noted that the Nlaka’pamux mixed roots and leaves of Mountain Valerian (Valeriana dio- ica) in a dried and powdered form and the powdered leaves and bark of the Dwarf Wild Rose (Rosa acicularia) with tobacco as flavouring. She also noted that some people smoked the leaves or bark of Red Osier Dogwood ( Cornus sp.), or mixed them with tobacco (Turner 1997, p. 169; 150; 107).

There is historic evidence that some groups prepared tobacco using stone mortars. Flat boulders were provided with a shallow depression on one side, and used to pound tobacco (Teit 1909, p. 474). Stone mortars for grinding tobacco were seldom used for other purposes and were confined mostly to the Kamloops and Bonaparte divisions of the Secwepemc. The anthropologist James Teit found only one old man who was positive that stone mortars, not the flat grinding slabs, were made by contemporary peoples, while all the other band members declared that they were made by Coyote in mythological times (Teit 1909, p. 500).

9.2.2 Stone Pipes

9.2.2.1 Historic and Archaeological Evidence

The practice of smoking is well documented in the archaeological record based on the presence of stone pipes. Straight tubular pipes, sometimes with a trumpet-like end, are an older style found on sites in the Southern Interior of British Columbia dating to around the last 1200-1000 years (Fig. 9.2). Most are found in the midFraser and Thompson River region and southern river valleys such as the Okanagan. Similar pipes are found along the Columbia River of Washington State. Sharpangled elbow pipes replaced the more traditional varieties of tubular pipes (Fig. 9.3) in historic times.

Of the many objects made of steatite, pipes are one of the most common items. Most of these have been found associated with burials. Sanger gives a suggested date of AD 1400-1750 for the Chase burial mound site. The site is located on a ridge-like formation extending into a floodplain of the South Thompson River in south central BC, three miles west of Chase. Much of this site was looted, but a few of the burials were systematically excavated. He shows 11 tubular pipes from the site in a photograph provided by Wilson Duff. All of these are of the tubular/trumpet type—the bowl flares out like a trumpet bell. Five are complete and the others fragmentary. A number of the pipes had an encircling ring at the junction of the bowl

and stem. Several were decorated with incised lines. One has a human head carved in bas-relief (Sanger 1966, p. 25; 1968a, p. 105; 165 Plate IV Fig. B).

The Texas Creek site, EdRk-1, located on the Fraser River 12 miles from the town of Lillooet, is composed of inhumations in pits dug into sandy terraces, promontories, and loose talus slopes. The site is thought to date between AD 1400 and 1600. The site assemblage contained four pieces of tubular pipes (three stems and one bowl fragment). These pipes are very similar to those described in ethnographies as the earlier tubular varieties. The pipe with the longest stem has a raised ring at the bowl junction. The bowl fragments indicate a gently expanding trumpet variety (Sanger 1968b). An example from a non-burial context is illustrated in Fig. 9.10.

Three partial tubular pipes were found with a burial in the Merritt or lower Nicola River area at site EaRf-6. The artifacts include two trumpet-shaped bowls that expand outward from a raised ring that defines the boundary of the bowl and stem. West (1934, p. 506) shows six pipe examples collected by Emmons from around Lytton, BC. Fifteen pipe fragments also were found at four house pits at the Keatley Creek site, which dates to approximately 1000 years ago (Hayden 2000a, p. 35-40; Hayden 2000b, p. 195-196).

In addition to tubular and elbow pipes, zoomorphic motifs are fairly common, such as the deer head carving and bird bowl illustrated in Fig. 9.4, or the bird head with a hole for a stem at the back and a broken extension above the head in Fig. 9.5. Borden attributes a small, seated human forming a pipe bowl as belonging to the Emery Phase (before 1250 AD), but admits that this Fraser River Canyon Phase is still poorly defined (Borden 1983, p. 156-7; Fig. 8:29a). Some of the pipes and other artifacts may have been imported as trade items, such as that in Fig. 9.6 (top), which was carved from a distinct type of raw material found in the Eastern USA. Other, rarer, examples include the thick wedge-shaped bowl in Fig. 9.6 (bottom right).

9.2.2.2 Historic Observations

Harlan I. Smith described tubular pipes that he observed Native peoples using in Lytton (Smith 1899, p. 154-158) and in Kamloops, BC (Smith 1900, p. 428-29). Teit noted that elders remembered seeing tubular pipes in use but they were not as common as elbow-shaped pipes. One tubular pipe was seen in use in eastern Washington as late as 1896 (Teit 1900, p. 300; see Smith 1913, Plates XIII and XIV).

Teit observed that in the decades leading up to the late 1890s, pipes were made mostly of stone with high, narrow bowls and long stems. He illustrated a variety of types, which included elbow pipes with lead inlay designs (Teit 1900 Fig. 271, Fig. 9.7). The material used was a dark greenish, slightly transparent soapstone and a soft slate, which, when rubbed with grease and smoked, turns a glossy black colour. Teit also noted that some pipes were made of sandstone, white clay, sagebrush-root, and antler. Carved designs in the pipes were once filled with red ochre, but in historic times they were infilled with melted lead or German silver (Teit 1900:300). Verne Ray, who collected information two generations later than Teit, notes that the Secwepemc still used straight tubular-shaped pipes and the Nlaka’pamux also used them along with elbow pipes. The latter group and the Stl’atl’imx used a mortised steatite to carve out pipe bowls (Ray 1942, p. 188).

Some pipes had a square piece at the bottom of the bowl with an attachment hole for a string connecting it with the stem, on which beads were often strung, or in the case of a shaman’s pipe, decorated with eagle feathers (Teit 1900, p. 300). This description may refer to the style of pipe shown in Fig. 9.8. Smith observed people in the Thompson River region winding string around the mouthpieces of their pipes to make them easier to hold in their mouths (Smith 1900, p. 428).

Teit notes that among the Okanagan the older tubular pipes had figures of animals carved along the top and others were carved like an animal’s mouth. There is one case in which a First Nation man named George Lezard from the Penticton Band provided the name Kalkalues for a steatite pipe with a lizard-like creature mounted on top. This appears in the notebook of Atkinson (1937) and is seen here as Fig. 9.9.

Teit’s reference to a “simple pipe bowl” in use may refer to pipes with an extension on the bowl (see Fig. 9.10) that fits into a wooden stem and had a raised ring defining the proximal end of the bowl (Teit 1930, p. 278). He mentions that a few men had small male images that they kept in their medicine bags and these had some connection with guardian spirits. Some of these were tubular pipes with anthropomorphic figures. They were rare and apparently had gone out of use long ago, as Teit could not find any old men who had ever seen them (Teit 1909, p. 603). The author observed one of these in a private collection in the 1970s. It was a full figure of a man with the pipe tube forming the centre of his body, arms and legs angled out to the side, and his head forming the bowl. Others have a human head only as in Fig. 9.11.

9.2.2.3 Manufacturing Techniques

During his ethnographic research in the early-twentieth century, Teit noted the use of scouring rush, and the practice of including “a mixture of grease and pitch of the black pine” to manufacture pipes (Teit 1900, p. 182). Scouring rush (Equisatum

hyemale) or “horsetail” is rough because of silica imbedded in the outer cell walls. This property makes an ideal abrasive for the finishing, smoothing, and polishing of pipe surfaces. Teit also noted that steatite used in pipe manufacture was cut using beaver tooth knives and bored with flaked stone drills (Teit 1909:474).

Decades later, some of these practices were still being used. The late Joseph Harris of the Penticton Museum (personal communication 1974) told the author that

his friend and predecessor Reginald Atkinson obtained information from George Lezard of the Penticton First Nation who was the last of the traditional carvers in British Columbia. Lezard carved soapstone pipes as well as animals and other items for the tourist trade with hacksaw blades, a variety of steel files, and a steel point as late as the 1960s (Sismey 1966).

Atkinson (1937) recorded that black soapstone was carved as it hardened and that pipes varied in size from 2-8 inches. He also noted that tubular pipes with wooden stems were smoked in an upright position. Lezard told him that a plant called mare’s tail (likely E. hyemale) was used as a file to wear off the rough surfaces. It was also used to smooth the bore after it was roughed out with a stone drill bit. The raw material that Lezard used came from a source on the Similkameen River. The author obtained some of this light-green coloured material and experimented with it, grinding with scouring rush and cutting with beaver teeth. These techniques worked well, especially with softer material that was recently dug out. Evidence in the form of distinct parallel lines seen in the primary shaping of the pipe indicates that even some of the old styles of pipes were being made with iron files (see Fig. 9.12). Finally, an example of a later and more angular-shaped soapstone pipe carved by a Stl’atl’imx man in 1908 is seen in Fig. 9.13.

9.2.3 Trade

Exchanges in pipes and raw material, occurring at the Tulameen River forks trade centre, involved people from the Similkameen, Okanagan, and Thompson River regions. Teit notes that pipes and pipestone of red, brown, green, mottled-yellowish, bluish, and grey colors were interchanged. Teit also suggests that the bright-red catlinite came from the east, mostly via the Kalispell people of Idaho, and the green soapstone from the Thompson River (Teit 1930, p. 254). Black soapstone was obtained in the Similkameen Valley, below the village of Keremeous.

A large variety of catlinite pipes were also traded into British Columbia in the historic period. The tomahawk pipe, second from right in Fig. 9.14, could be purchased at Hudson Bay Company stores (Teit 1900, p. 300; 1909). When speaking about the Lake and Okanagan First Nations from information obtained in the 1920s, Teit indicated that trade goods had gradually filtered through the larger region, but in some places a few people occasionally made special long distance trading trips across mountain ranges and through uninhabited country to distant trading partners. After the introduction of horses (c. mid-1700s), large parties undertook these trips more regularly.

When routes opened in July and August, the Similkameen and Okanagan sometimes crossed the Cascade Mountains and visited the people of Hope on the lower Fraser River. These visits occurred annually with the regular use of horses. Regular trade also occurred from The Dalles area on the Columbia River to the Okanagan (Teit 1930, p. 250; 254). Simon Fraser observed a pack horse along the lower Fraser in 1808 (Lamb 1960), but an early Spanish account suggests the people from the interior were coming on horseback to the Fraser River Delta area as early as 1791 (Wagner 1933).

9.2.4 Interior Plateau : Ritual Use and Status of Pipes

Pipes described in a traditional story involving the characters Hare and Fox suggest a status difference in the types of pipes. Fox was smoking a fine stone pipe carved and incised with numerous designs, while Hare’s pipe was made of wood (Teit 1909, p. 625). The stems of most stone pipes were made of the preferred Maplewood and were up to a foot and a half in length.

As Teit observed in 1900, the custom of passing the pipe around a circle of men was still being practiced to some extent. This was done before making speeches or discussing business transactions. The pipe was passed around while a person spoke at gatherings. It was customary, when a man or woman wanted to converse with a friend, to prepare a pipe and sit down for a smoke, and everyone would take turns puffing. The pipe was passed around in the direction of the movement of the sun. (Teit 1900, p. 302).

Teit notes that among the Okanagan ceremonial smoking was practiced at the beginning of serious undertakings, such as councils. What is described as a large pipe seems to play a special role in a number of ceremonies. During a Spring Dance at fishing sites, all the middle-aged and elderly men gathered after sunset in the house of the head chief for dances. Here they had a ceremonial smoke that included passing around a large pipe. Pipes smoked at gatherings or councils typically were much larger in size than ordinary ones (Teit 1900, p. 300 and 335; 1930, p. 278). It is possible that the pipe in Fig. 9.8 may be one of these large pipes.

9.2.5 The Social and Regional Context of the Interior Plateau Pipes

Stone pipes from the Interior Plateau of BC were clearly introduced from the Columbia River area to the south. The work of Harlan I. Smith (Smith 1899, 1900, 1910), James Teit (1900, 1906, 1909, 1928, 1930), and others showed the similarities between these areas but explanations for these similarities were not articulated until recent times. Hayden and Schulting (1997) show stone pipes as part of a larger assemblage of what they define as mainly prestige artifacts that provide evidence of an Interior interaction sphere. As this northwestern Plateau interaction sphere transcends language and cultural boundaries, they argue that factors other than common historical origins explain the similarities of artifacts among these Plateau groups. Pipes are seen as part of the prestige items (and I would add ritual activities) acquired by a class of elites who seek to maximize their power and wealth at the tribal level. These individuals gain their status “in part, by establishing trading, marriage, ideological, military, and other ties to elites in other communities and regions. They use these ties to monopolize access in desirable regional prestige goods and to enhance their own socioeconomic positions” (Hayden and Schulting 1997).

Furthermore, Hayden and Schulting (1997) view these traded prestige items as being concentrated in communities that have the greatest potential to produce surplus and to develop socioeconomic inequalities. The extensive examination of pipes discussed here does not change this general conclusion. My study, however, shows a more diffuse distribution of pipes than is shown by Hayden and Schulting.

Distribution centres where most pipes are found may be a product of the intensity of where archaeologists have been undertaking their work or where construction activities have uncovered burials. For example, burials are often located in sandbanks and talus slopes in narrow canyons, where they are frequently uncovered by roads and railway lines.

Although Hayden and Schulting refer to the interaction period as pertaining to what are termed the Plateau and Kamloops horizons in British Columbia (400 BC-1750 AD) pipes only occur in the later part of this time period (between 750 and 950 AD). Prentiss and Kuijt (2012) argue on the basis of dating sequences that people in this region did not have the capacity to accumulate excess material wealth before 750 AD when populations reached their maximum. In the large excavated village sites such as Keatley Creek, Bridge River, and the Bell site, many of the early pipes are fragmentary. For example, a child burial from house pit 19 at the Bell site contained five pipe fragments—all made into pendants. The value of the raw material from which pipes were made is likely the reason that broken pipes were reworked as functional pipes or cut into sections to create other kinds of artifacts. Figure 9.15 shows five steatite bowl fragments from site EeRk-4, near Lillooet, made into pendants. These pendants were associated with obvious trade goods in the form of 246 dentalia shells from the coast. This leads one to be cautious about interpretations of the presence of pipe fragments as evidence of smoking activities.

I argue, as an extension to Hayden and Schulting’s ideas of elite connections, that these connections were enhanced in the late pre-contact period by the long distance effect of European fur trade activities on the eastern portions of the continent. Changes in pipe styles from straight tubular pipes to European angled pipe bowls may be an extended product of European pipe styles found further east and their entry into these more western trade networks before the presence of Europeans in the local region.

9.3 Northern Coast of British Columbia and S.E. Alaska

9.3.1 Tobacco: Its Origin, Use, and Preparation

The Nicotiana quadrivalvis (bigelovii variety) is the type of tobacco cultivated on the Island of Haida Gwai (Queen Charlotte Islands) and some islands in southern Alaska in Tlingit territory. The Tlingit and Haida were cultivating N. quadrivalvis before the European trade period of the 1770s and traded it to the Nisga’a, Coast Tsimshian, and Tahltan groups on the mainland. Although popular among the people of the Northern Coast, N. quadrivalvis (bigelovii variety) is Native to California and southern Oregon where it was sometimes cultivated (Linton 1924; Harrington 1932; Heizer 1940; Kroeber 1941). Quadrivalvis was introduced from the West through Idaho and into the northern Plains of Montana and North Dakota as a cultivated plant. It was also cultivated in the Columbia River rapids area of Washington State. This eastern variety is known as the sub-variety quadrivalvis (Haberman 1984). The same aboriginal term for this plant “op” or “ope,” is used throughout much of its geographic range despite the fact that a number of different language groups are represented (Dixon 1921, 1933; Driver 1969). There is no known historic connection with this plant on the northern coast and the area of its origin much further to the south.

In the 1880s, Niblack’s (1890, p. 333) First Nation consultants indicated that the origin of the pre-European tobacco plant in this region was Haida Gwai (Queen Charlotte Islands). Captain Vancouver observed the cultivation of tobacco at Kootznahoo or Admiralty Island [near Point Caution] in 1783. He noted that small square garden patches of a species of tobacco, which he understood to be commonly cultivated on the Queen Charlotte’s Islands (Vancouver 1798), could be found in the vicinity of houses. Over 100 years later, Charles Harrison recorded a Haida story he called The Tobacco Legend. The story indicates that the Haida obtained tobacco from a tree that was safeguarded by a powerful deity who lived far inland on a mountain in the Stickeen country. They went to this location on top of a mountain and shot seeds down from the tree, took them home, and planted them (Harrison 1925, p. 141). The importance of tobacco is also revealed in the Story of Those Born at Skedans. When many killer whales lay in Canoe Cove in a threatening manner, they caused the whales to leave by laying out tobacco and lime for them, which was taken up by a mythical creature resembling a porpoise who “took it into its mouth.” (Swanton 1905, p. 88).

Native inhabitants of the Northern Coast did not smoke N. quadrivalvis. Rather, they mixed it with a lime solution and sucked the substance, as was common in several regions from Central America to California (Dawson 1880; Chittenden 1884; Deans 1890; Kroeber 1941; Newcombe 1897; Turner and Taylor 1972). The leaves were cured by drying and crushed in a stone mortar. A separate mixture of lime was made by heating up abalone or clam shells, putting them in cold water, and then crushing them into a fine white powder. The tobacco was put in the mouth and the finger dipped in the pasty lime and put into the centre of the tobacco. The Tlingit also made it into pellets with spruce or cedar gum to be sucked.

Similar to the Interior Plateau, some groups in northern British Columbia also used stone tobacco mortars to process tobacco. In the 1880s, Niblack described an Alaskan raven-shaped stone pestle for preparing tobacco and observed stone tobacco mortars in old houses (Niblack 1890, Plate 63). Large stone tobacco mortars have been collected from historic house ruins and disturbed surface areas of archaeological sites on the northern and central coast of British Columbia. As none have been found in a systematic excavation project, we can only speculate from current evidence that these mortars are confined to the later pre-contact or early historic time period. The example seen in Fig. 9.16 is engraved with a scene of men in a canoe hunting sea otters.

9.3.2 Smoking Pipes

In the sixteenth century, European colonists acquired domesticated species of tobacco in the West Indies. Through Russian trade, it diffused across Siberia to Alaska by, at least, the late 1700s (Khlebnikov 1976). When Russian leaf tobacco and pipes were introduced to the area in the late-eighteenth century, northern groups turned readily to smoking and the making of elaborate carved pipes for smoking at feasts and funerals. Many of the Tlingit pipes resemble those used in Siberia and China, with bowls often composed of a straight piece of metal or stone stuck into a hole at the end of a long curved stem made out of wood, bone, or other materials. The Tlingit held a smoking feast in which tobacco was offered via the fire to all the dead of the clan hosting the feast. At these events clan mourning songs were sung and the clan history recalled.

Khlebnikov, who was at Sitka Alaska from 1817 to 1832, noted that “Virginia tobacco” was being traded to the Tlingit for eight mink skins in 1825. He also described the Tlingit making slate pipes with carved representations of bird eyes and beaks (Khlebnikov 1976, p. 39, 69). After the historic introduction of smoking numerous carved pipes appear with elaborate animal shapes being the most common among the Tlingit and Tahltan peoples (Fig. 9.17). A copper or iron pipe was often inserted inside the bowl or a metal cap placed on top (Fig. 9.17, right). It is known that chlorite, serpentine, and talc are found in the Sitka region and were used in pre-contact times to make labrets. It is likely that this already known indigenous technology was later used for pipe making.

9.3.2.1 Haida Argillite Pipes

Among the Haida, there were two varieties of pipes, one for ordinary use copied from commercial styles and another, which involved more elaborate animal designs, used for ceremonial occasions. Tobacco and pipes were provided for all guests at funerals after the wailing period (Harrison 1925, p. 79). Argillite pipes were made in the “ceremonial pipe form” beginning about 1829, and represented combinations of humans and animals. More elaborately carved “Haida-motif panel” (Fig. 9.18) and “ship panel” pipes (Fig. 9.19) developed later (Macnair and Hoover 2002). European clay pipes became common and were being copied by the Haida in argillite by at least 1847. Trade pipes from the mid-nineteenth century had both Haida and European figures and sometimes the addition of ivory pieces. Late period pipes (post-1880s) change in style with more traditional Haida figures (Macnair and Hoover 2002, p. 119). Many of these were purely decorative for the European market. In contrast, the Tlingit pipes from the early 1800s “in almost every instance represent the family crest” (Emmons 1911, p. 64) of their owners and were often made of exotic woods from the stocks of trade guns. The bowls of wooden pipes were lined with metal, such as a section of musket barrel and, in later times, stems were extended using a section of brass shell cartridge.

Smoking tobacco was traded inland to the Tahltan after it was introduced by Europeans in the early-nineteenth century. The Tahltan made elaborate versions of European style elbow pipes and used them as ceremonial pipes during feast occasions. Prior to the time of smoking, the coastal practice of mixing burnt shell, charred tree bark, and tobacco involved the reduction of these ingredients to the form of a paste that was rolled into pea-sized pellets. A pellet “was placed between the lower lip and the gum and sucked, necessitating constant expectoration.” Emmons recorded that this “nicotine plant” cultivated by the Tlingit, was “said to have been brought up the Stikine River and planted in small garden patches at the old village of Tutchararone, near the mouth of the Tahltan river” (Emmons 1911, p. 63).

9.4 Pipes on the Southern Coast of British Columbia

Archaeological and ethnographic investigations of indigenous groups of the Southern Coast of BC and Northern Coast of Washington indicate that these communities did not smoke at the time of the coming of the first Europeans (Drucker 1965, p. 45). However, small numbers of stone pipes, mostly fragmentary, have been found on the Southern Coast of BC. Unfortunately, most are not from dated contexts and no residue analysis has been undertaken on any of these pipes. We cannot rule out that some smoking activities were practiced for short periods of time in some areas, but the limited number of pipes and the absence of sufficiently dated pipes suggests that trade in valued raw materials may be the explanation for the occurrence of pipes in this region.

In very early historic times, some Coast Salish speaking peoples in the southern part of Puget Sound smoked tobacco, which they obtained in trade, along with stone elbow pipes, from east of the Cascades. In the early 1800s, Alexander Ross noted an Okanagan chief had formally been in the habit of going on trading excursions to the coast (Ross 1956, p. 37). No pipes are mentioned in regard to this early trade, but we may speculate that European pipe styles were introduced at this time. Smoking in the Puget Sound area in early historic times seemed to be associated mostly with Shamanistic ritual activities (Spier and Sapir 1930, p. 269).

Local plants were used in the historic period to bulk up or give flavour to the tobacco introduced by Europeans. In western Washington State, yew ( Taxus brevifolia) needles were pulverized and used in place of tobacco for smoking. The Snohomish mixed them with kinnikinnick and later with tobacco. Gunther’s First Nations consultants suggested that before the introduction of European tobacco, the leaves of kinnikinnick were pulverized and smoked alone. Later, they were used to stretch the small supplies of tobacco available. The Chehalis say that if one swallows the smoke of kinnikinnick, it produces a drunken feeling. A Klallam consultant said that either kinnikinnick or yew leaves were mixed with tobacco, but kinnikinnick was never mixed with yew because it was too strong (Gunther 1945, p. 16, 44).

9.4.1 The Lower Fraser River Area

Stone elbow style pipes are found in historic period sites on the lower Fraser River. Only fragmentary portions of older style tubular pipes have been found in this region, such as those at Port Hammond (Smith 1903, p. 180-181). The undated rattle-snake-man pipe seen in Fig. 9.20 was found in a site near the junction of the Fraser and Harrison Rivers. This could be a product of some ritual activity involving smoking but could just as likely be a trade item from the neighbouring Interior. Two pipe bowl pieces shown in Fig. 9.21, from the same general area, are in the process of being sectioned—probably for use as ornaments.

9.4.2 Vancouver Island

Only one complete pipe bowl of a unique type (Fig. 9.22) has been found at the False Narrows site, DgRw-4, on Gabriola Island off the east coast of the Vancouver Island (Burley 1988). Although portions of this site date to over 2000 years ago, the context of this artifact is not known. The fact that it has two small holes drilled on both sides just below the rim suggest that it was used for ornamental purposes, and it is different from other Southern Coastal styles.

Small numbers of fragmentary pipes have been found from the Saanich peninsula (Smith 1903, p. 181) and at the Pedder Bay site, west of Victoria, where five tubular pipe bowl fragments and one stem fragment were found (Fig. 9.23). It is significant that four of the five bowls have cut marks that indicate they were to be sectioned. These sites date after about 800 years ago. It is uncertain as to whether these were used for smoking or are raw material trade items from the Interior Plateau.

9.5 Discussion

The type of tobacco used in the far northern areas of northwestern North America has been the subject of much discussion. It is often thought that one of the southern species of tobacco (e.g., West 1934, p. 102). However, it is more likely that the

tobacco used in this region is a species with a natural range from central Oregon to the Mexican border that spread as a result of human cultivation from an area extending eastward to the Missouri River and northward to the Columbia River (Turner and Taylor 1972, p. 255). I suggest that such varieties of cultivated tobacco had a much wider distribution in the past, and that distribution patterns changed through time along the Pacific Coast of North America. Tobacco was possibly grown for ritual uses in the warmer regions of the Southern Coast of BC. The historic tobacco industry was successful in the warmer parts of the Southern Coast (Lewis 1980). At present, there is only minimal archaeological evidence of the use of stone pipes for smoking.

If pipes were used on the Southern Coast, we cannot yet rule out that both pipes and tobacco could have been traded from outside and used in a limited way by ritual specialists. The existence of N. quadrivalvis (bigelovii variety) on the Queen Charlotte Islands further north may simply be the northern extent of what was once a longer coastal continuum of the species from California to the islands of southwest Alaska. Botanist David Douglas found specimens of N. quadrivalis near the mouth of the Columbia River in 1829, suggesting that the distribution of the species may have been more extensive in the late pre-contact period (Douglas 1914). However, the species subsequently disappeared from the area. Botanist B.A. Meilleur suggests the Haida acquired the tobacco seeds in trade from the Columbia River (Meilleur 1979).

9.6 Conclusions

The archaeological evidence clearly places the introduction of smoking pipes on the Southern Plateau of British Columbia by the start of the Kamloops Horizon around 1250 AD and possibly 200 years earlier. This practice continued into historic times with a change to more European-style pipes. Traditional tubular pipes with more elaborate carved depictions of humans and animals were more common before the early nineteenth century.

Although it is known that sharp-angled elbow pipes replace the more traditional varieties of tubular pipes in the historic times, there is some suggestion that the type transition may have begun more gradually in proto-historic times as a result of First Nations peoples copying old European styles from eastern North America. Elbow pipes began replacing the older tubular forms by the 1830s and the placing of lead inlays in designs was well established by the 1890s. Increasingly during the fur trade period more exotic varieties of pipes from eastern North America began to filter into British Columbia. Catlinite pipes were being purchased for use by the 1840s.

Speakers of Salishshan languages with similar cultural practices, such as the Guardian Spirit and Dance Complex, extended from southern British Columbia into the Middle Columbia River region (Ray 1939). These cultural relations likely extended back in time and account for the similarity of pipe styles throughout the region. Tobacco cultivation and pipe smoking appear to have occurred slightly earlier in the middle Columbia River region, which suggests the practices spread to the north.

The Haida and Tlingit practice of sticking burnt abalone shell paste (lime) into rolled tobacco balls that were sucked was also practiced by the Central and Southern Miwok and Yokuts, Tubatulabal, Kitanemuk, and Costanoans of California (Barrett and Gifford 1933, p. 195; Heizer and Whipple 1960, p. 24; Kroeber 1941). The shared practice strongly indicates the likelihood of previous contacts and connections between peoples of these areas or the previous existence of intermediate groups with the same practice. It should be noted that Heizer and Whipple (1960) mistakenly use the terms chewing and eating, rather than the more correct term of sucking, when referring to tobacco use in these areas.

Current archaeological and historical information suggests that Europeans introduced pipe smoking in the late-eighteenth to early-nineteenth centuries in Alaska and Northern British Columbia. First Nations adapted this new practice with the production of a wide range of elaborately carved wood, bone, ivory, and slate pipes representing both European and traditional subject matters. Sproat observed in the 1860s that many First Nations communities on the southern coast of British Columbia were using what he called the blue-stone or Tsimshian pipes traded from the northern coast (Sproat 1868).

Stone elbow pipes as well as clay pipes were used on the southern coast in early historic times, as a result of the adoption of the European smoking habit. Pipe fragments are found scattered throughout the region, but in very small numbers. It is common to see pipe fragments being used as raw material for making other artifacts—such as pendants. Some may have been part of a ritual-related smoking complex that is not well defined or dated. Unlike the Interior Plateau, we cannot make a connection with ancient and historic pipe smoking. People on the southern coast apparently did not smoke according to early European accounts. Thus, further work needs to be done on the southern coast to determine if pipe smoking did occur in pre-contact times.

References

Anderson, J. R. (1925). Trees and shrubs. Food, medicinal, and poisonous plants of British Columbia. Victoria, British Columbia, Canada: King’s Printer/Department of Education.

Atkinson, R. N. (1937). Reginald N. Atkinson. 1937 notebook. Penticton, British Columbia, Canada: Penticton Museum.

Barrett, S. A., & Gifford, E. W. (1933). Miwok material culture. Bulletin of the Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee, 2(4), 117-376.

Borden, C. E. (1983). Prehistoric art of the lower Fraser region. In Indian art traditions of the Northwest Coast (pp. 131-165). Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada: Archaeology Press/ Simon Fraser University.

Burley, D. V. (1988). Senewelets. Culture history of the Nanaimo Coast Salish and the false Narrows Midden. Memoir No. 2. Victoria, British Columbia, Canada: Royal British Columbia Museum.

Chittenden, N. H. (1884). Hyda land and people: Offi cial report of the exploration of the Queen Charlotte Islands for the Government of British Columbia. Victoria, British Columbia, Canada: King’s Printer.

Dawson, G. M. (1880). Report on the Queen Charlotte Islands, 1878. Geological Survey of Canada, 5, 239; plate xiv. Montreal, Quebec.

Deans, J. (1890). The Haida Kwul-ra or Native tobacco on the Queen Charlotte Islands. American Antiquarian, 12, 48-50.

Dixon, R. B. (1921). Words for tobacco in American Indian languages. American Anthropologist, 23, 19-49.

Dixon, R. B. (1933). Tobacco Chewing on the Northwest Coast. American Anthropologist, 35(2), 146-150.

Douglas, David (1914). Journal kept by David Douglas during his travels in North America 18231827, together with a particular description of thirty-three species ofAmerican oaks and eighteen species of Pinus, with appendices containing a list of the plants introduced by Douglas and an account of his death in 1834. Published under the direction of the Royal Horticultural Society.

Driver, H. C. (1969). Indians of North America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Drucker, P. (1965). Cultures of the North Pacific Coast. Scranton, PA: Chandler.

Emmons, G. T. (1911). The Tahltan Indians. University of Pennsylvania. The Museum. Anthropological Publications, 4(1), 1-120. Philadelphia, PA: The University Museum.

Gunther, E. (1945). Ethnobotany of Western Washington. University of Washington Publications in Anthropology, 10(1), 1-62. Seattle.

Haberman, T. W. (1984). Evidence for aboriginal tobaccos in eastern North America. American Antiquity, 49(2), 269-287.

Harrington, J. P. (1932). Tobacco among the Karuk Indians (Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 94). Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institute.

Harrison, C. (1925). Ancient warriors of the North Pacific: The Haidas. Their laws, customs and legends, with some historical account of the history of the Queen Charlotte Islands. London: H.F. & G. Witherby.

Hayden, B. (2000a). Dating deposits at Keatley Creek. In B. Hayden (Ed.), The ancient past of Keatley Creek (Taphonomy, Vol. I, pp. 35-40). Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada: Archaeology Press/Simon Fraser University.

Hayden, B. (2000b). Prestige Artifacts at Keatley Creek. In B. Hayden (Ed.), The Ancient Past of Keatley Creek (Socioeconomy, Vol. II, pp. 189-202). Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada: Archaeology Press/Simon Fraser University.

Hayden, B., & Schulting, R. (1997). The Plateau Interaction Sphere and Late Prehistoric Cultural Complexity. American Antiquity, 62(1), 51-85.

Heizer, R. F. (1940). The botanical identification of Northwest Coast tobacco. American Anthropologist, 42(4), 704-706.

Heizer, R. F., & Whipple, M. A. (1960). The California Indians. A source book. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Johnson, O. W. (1969). Flathead and Kootenay. The rivers, the tribes and the region’s traders. Glendale, CA: Arthur H. Clark.

Khlebnikov, K. (1976). Colonial Russian America. Kyrill T. Khlebnikov’s reports, 1817-1832. Translation with introduction and notes by Basil Dmytryshym and E.A.P Crownhart-Vaughan. Portland, OR: Oregon Historical Society.

Kroeber, A. L. (1941). Culture element distributions: XV, Salt, Dogs, Tobacco. University of California Archaeological Reports, 6(1), 1-20.

Lamb, K. (1960). The letters and journals of Simon Fraser, 1806-1808. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Macmillan.

Lewis, Zane. (1980). Up in smoke: The British Columbia tobacco industry. Unpublished manuscript (pp. 40). History Division, Royal BC Museum, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada.

Linton, R. (1924). Use of tobacco among North American Indians (Anthropological Leaflet 15) (pp. 27). Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History.

Macnair, P., & Hoover, A. L. (2002). The magic leaves. A history of Haida argillite carving. Victoria, British Columbia, Canada: Royal British Columbia Museum.

Meilleur, B. A. (1979). Speculations on the Diffusion of Nicotiana Quadrivalis Pursh to the Queen Charlotte Islands and Adjacent Alaskan Mainland (Syesis, Vol. 12, pp. 101-104). Victoria, British Columbia, Canada: The British Columbia Provincial Museum.

Newcombe, C. F. (1897). Diary of 1897. Newcombe Family Papers. Royal B.C. Museum Archives, Additional Manuscript 1077, Vol. 33, file 5.

Niblack, A. P. (1890). The Coast Indians of Southern Alaska and Northern British Columbia; based on the collections in the United States National Museum and on personal observations of the writer in connection with a survey of Alaska in the seasons of 1885, 1886 and 1887. Annual Report of the United States National Museum for the Year Ending June 30, 1888 (pp. 225386). Washington, DC

Prentiss, A. M., & Kuijt, I. (2012). People of the Middle Fraser Canyon. An archaeological history. Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada: UBC Press.

Ray, F. V. (1939). Cultural relations in the Plateau of Northwestern America (Publications of the Frederick Webb Hodge Anniversary Publication Fund, Vol. III). Los Angeles: The Southwest Museum Administrator of the Fund.

Ray, V. F. (1942). Culture Element Distributions: XXII, Plateau (Anthropological Records 2nd ed., Vol. 8). Berkeley, CA: University of California.

Ross, A. (1956). The fur hunters of the far west. In Spalding K. A. (Ed). Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Sanger, D. (1966). Indian graves provide clues to the past. The Beaver, Spring (pp. 22-27).

Sanger, D. (1968a). The Chase Burial Site EeQw-1, British Columbia. In National Museums of Canada, Bulletin 224. Contributions to Anthropology VI: Archaeology. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Sanger, D. (1968b). The Texas Creek Burial Site Assemblage, British Columbia. In National Museum of Canada, Anthropological Papers Vol. 17, No. 1 (pp. 23). Department of the Secretary of State, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Sismey, E. D. (1966, September 4). Slate carving—A fading art. The Seattle Times. Sunday.

Smith, H. I. (1899). Archaeology of Lytton, British Columbia. Jessup North Pacific Expedition Memoir. American Museum of Natural History, 1(3), 129-163.

Smith, H. I. (1900). Archaeology of the Thompson River Region, British Columbia. Jessup North Pacifi c Expedition Memoir. American Museum of Natural History., 1(3), 401-442.

Smith, H. I. (1903). Shell-heaps of the lower Fraser River, British Columbia. The Jessup North Pacifi c Expedition. Memoir of the American Museum of Natural History, 2(4). New York.

Smith, H. I. (1910). The archaeology of the Yakima Valley. Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History (Vol. 6). New York: AMNH Trustees.

Smith, H. I. (1913).The archaeological collection from the Southern Interior of British Columbia. Museum of the Geological Survey, Canada. Department of Mines. Geological Survey. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Government Printing Press.

Spier, L., & Sapir, E. (1930). Wishram ethnography. University of Washington Publications in Anthropology, 3(3), 151-300.

Sproat, G. M. (1868). Scenes and studies of savage life. London: Smith, Elder.

Swanton, J. R. (1905). Haida texts and myths: Skidegate Dialect, Smithsonian Institute. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin No. 29. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Teit, J. (1900). The Thompson Indians of British Columbia. In Franz Boas (Ed) The Jessup North Pacific Expedition. Memoir of the American Museum of Natural History Vol. 1, No. 4. New York.

Teit, J. (1906). The Lillooet Indians. In F. Boas (Ed), The Jessup North Pacifi c Expedition. Memoir of the American Museum of Natural History, Vol 2, No. 5. New York.

Teit, J. (1909). The Shuswap. In F. Boas (Ed.), The Jessup North Pacifi c Expedition. Memoir of the American Museum of Natural History Vol. 1, No.7. New York.

Teit, J. (1928). The Middle Columbia Salish. University of Washington Publications in Anthropology 2(4)83-128.

Teit, J. (1930). The Salishan tribes of the Western Plateaus. In F. Boas (Ed). Forty-fifth annual report of the Bureau of American Ethnology: To the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1927-1928, United States. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Turner, N. J. (1997). Food plants of interior first peoples (Royal British Columbia Museum handbook). Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada: UBC Press.

Turner, N. J., & Taylor, R. L. (1972). A review of the Northwest Tobacco Mystery. Syesis, 5, 249-257.

Turney-High, H.H. (1974). Ethnology of the Kutenai. In Memoirs of the American anthropological association, No.56. Millwoods, NY: Kraus Reprint.

Vancouver, G. (1798). A voyage of discovery to the North Pacifi c Ocean and round the world in the years 1790-95 (Vol. 3). London: Robinson.

Wagner, H. R. (1933). Spanish explorations in the strait of Juan de Fuca. Santa Anna, CA: Fine Arts Press.

West, G. A. (1934). Tobacco, pipes and smoking customs of the American Indians: Part 1, text. In S. A. Barrett (Ed.), Bulletin of the public museum of the city of Milwaukee (Vol. 17, pp. 1-994). Milwaukee, WI: Trustees of the Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee.