2005.

By Grant Keddie

The Chuchawaytha Rock Shelter Pictographs.

Since reading the Midden article by Darius Kruger (2005), I thought I should add some unique information to his favorite ancestral site – the Chuchawaytha Rock Shelter, DhRa-2. This Similkameen region site has been referred to in earlier literature as the Hedley cave site. There has been some confusion regarding this location perpetuated by non-First Nation stories about early visits by Spaniards.

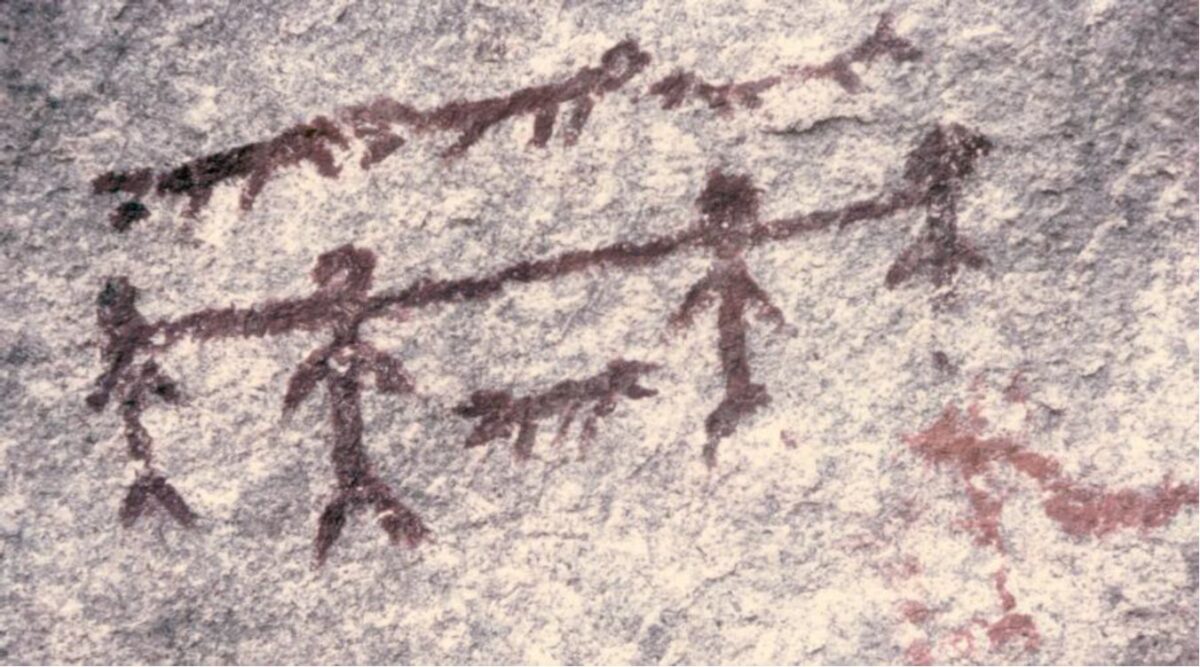

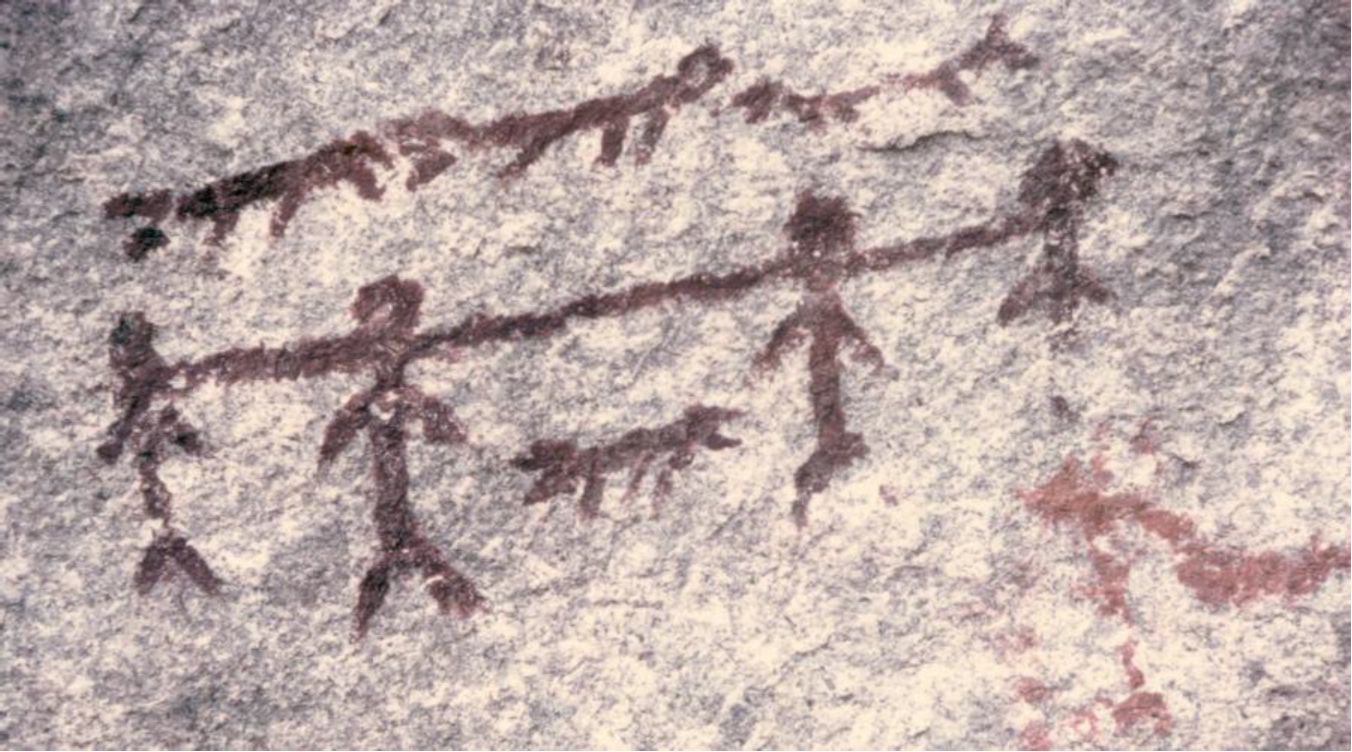

Two clusters of images referred to as “the horseback riders” and “the prisoners” have often been misinterpreted by non-First Nations, as a single unit that represents Spaniards on horseback with ropes tied around the necks of a group of First Nation prisoners. This interpretation is an attempt by non-First Nations to fit these images with a story about Spanish visitors to the area before the 19th century. These two clusters are clearly unrelated – based on both physical appearance and Similkameen oral tradition.

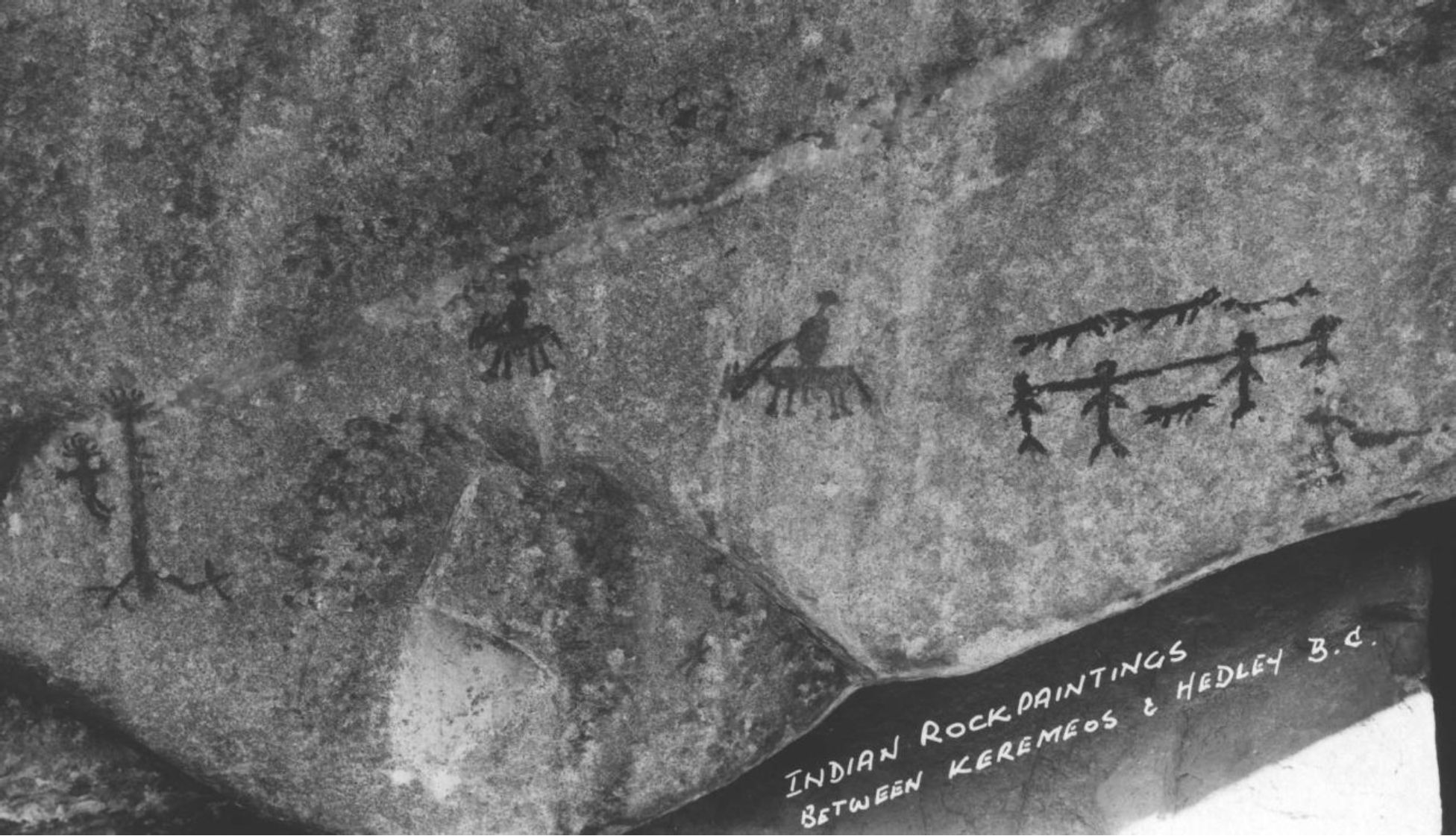

Information on this site was provided to me by Joseph (Joe) Harris of Penticton in 1974. Joe lived in the Okanagon area since 1917. He was an active member of the Okanagan Historical Society and had a keen interest in Pictograph sites. Joe photographed sites in the 1930s, and in 1949, published: “Indian Pictographs in South Central British Columbia”.

Joe received information from longtime residence Duncan Woods of Penticton (Died 1936, Age 76). Woods told Joe that he was provided with information about the Hedley cave site by a Similkameen First Nation named Francois Tomoican. I assume that the person referred to is Francois Tomar who died May 16, 1917 at the age of 60 on the Lower Similkameen Skemeoskuankin Reserve.

Francois told Woods that he was one of the people who painted pictographs in Hedley cave, while on a spirit quest as a youth. The figures he painted included the group of four people with dog-like animals and the line behind the people – possibly the latter could be an “earthline” as described at other sites?

Francois did not give any meaning to the glyphs other than saying he painted this group, and not the paintings of the men on horseback. The people-dog panel is a distinct dark red color different than the lighter red of the nearby painting of men on horseback. If Francois Tomar is the same person as Francois Tomoican, the painting would date to about 1871, when he was around 14 years old.

When James Teit visited the Similkameen in 1907, he provided First Nation interpretations of the figures at Hedley cave. One of those described as “men on horseback” was shown with two head feathers, suggesting they were First Nation riders. The group I attribute to Tomoican was described as “people” and “dogs or other animals with open mouths” (1930:285, fig.22). These two groups were not described as related or having associated stories.

In his 1949, publication Joe Harris comments of the Hedley Cave pictographs: “This group of paintings depicts men on horseback, with two reins extending from the horse’s head. They are of fairly recent origin. A story has been handed down by word of mouth to the effect that this group was done by a mature native and depicts an incident connected with the coming of the first white men”.

Joe Harris also attributed the story about the “Place where Justice was administered” as part of the above story which refers to non-First Nations men being killed for insulting a First Nations woman. But earlier, John Goodfellow (1928), attributed the latter story to a different location, now recorded as DiRa-3, and what he called “The Justice pictograph”. Goodfellow stated: “This is the place pointed out as the ‘Place where Justice was administered’”. In a second statement he specified that: “It is known locally (among the Indians) as the Place where Justice was administered”.

John Corner (1968) identified this other site (DiRa-3), based on Goodfellow’s glyph designs, and called it the “Stepping Stones” site – Corner’s site no. 29.

It appears that Goodfellow obtained the Justice Story from local band member Ashnola John. It was Ashnola John’s eldest brother who was the “hero of the tale”. Estimating that the elder brother was not born before 1820, would place the events of the story after the 1840s or 1850s when he was in his early adulthood.

Conclusions

Although there is a First Nations story about some Euro Americans being killed in the 19th century, the interpretation that the story is earlier and applies to Spaniards is a non-First Nation development. Part of the Spanish story came out of the use of Spanish names in the area, which is most likely a result of Mexican mule drivers living in the area during the Gold Rush period.

Spanish objects supposedly found in the region appear a bit elusive. One artifact was described as “a piece of Spanish armor”. I examined this artifact in the Princeton Museum in 1981. I recognized that it was a small piece of an early 20th century Chinese brass table with parts of engraved dragon motifs – just like the one I had at home.

Although there might appear to be some confusion on which site is the “Place where Justice was administered”, the earlier and more direct associations with First Nations consultants on the subject by Goodfellow, would suggest that Hedley cave was not the location pertaining to the older tradition, but that of site DiRa-3.

The fact that no stories were elicited by First Nations consulted by Teit on the specific meanings of the glyphs at both DhRa-2 and DiRa-3 does not help us here.

It was likely, the presence of the images of horseback riders at this site that caused non-First Nations, including Joe Harris, to associate the location with both the traditional story and the later developed story about the involvement of Spaniards.

The pictograph images associated with this rock shelter undoubtedly represent the spirit quest activities of a number of Similkameen First Nations; we may now be able to put a name to one of those individuals – Francois Tomoican.

References

Corner, John. 1968. Pictographs (Indian Rock Paintings) of in the Interior of British Columbia, Wayside Press Ltd., Vernon, B.C.

Goodfellow, J. C. 1928. Pictographs of the Similkameen Valley of B.C. Museum Notes, 3:2:14-16&23-24. Art, Historical and Scientific Association of Vancouver, B.C.

Harris. Joseph G. 1949. Indian Pictographs in South Central British Columbia. Okanagon Historical Society Report #13, pp. 22-23.

Kruger, Darius. 2005. Pictographs in the Upper Similkameen Traditional Territory. A Guided Tour. The Midden 37(4)5-8.

Teit, James 1930. Salishan Tribes of the Plateaus. 45th Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1927-1928.