By Grant Keddie. August 2013.

Japanese Shipwrecks in British Columbia – Myths and Facts

The Question of Cultural Exchanges with the Northwest Coast of America.

Arguments have been presented by Quimby (1989; 1985; 1948) and other proponents going back 135 years ago (Anderson 1863) that Aboriginal Cultures of the Northwest Coast have been strongly influenced by the effects of Japanese shipwrecks. If iron from Japanese ships was available on a regular basis and ship survivors introduced even the occasional new idea – such as the development of a new fish net technology with a pronounced higher efficiency than pre-existing technology – the influence on aboriginal cultural may have been substantial.

Determining the past existence and frequency of the landing of Japanese vessels along the coast of British Columbia is important in assessing the possible extent of influences by cultures of Japan on the cultural history of local aboriginal populations.

Proponents of this externally induced change were strongly influenced by two factors: (1) the early publications on the subject of shipwrecks by Charles Brooks (1876) and Horace Davis (1872a; 1872b) and (2) the fact that iron goods were commonly observed by the first European explorers to this area.

The second factor has been given more significance by Archaeological evidence of iron being used in at least 42 tool hafts along with 2 pieces of bamboo, in a late 16th to early 17th century archaeological context at the Ozette site in Washington state (Gleeson 1980); the recent finding of an iron adze blade dating to the 15th century from a site on the Columbia River (Ames 1998; 1999); an iron tool associated with 15th century human remains from the Tatshenshini River area of northwestern

British Columbia (Beattie et.al. 2000) and pre-contact evidence of bone and wood working suggestive of the use of metal tools (Keddie 1990).

I have examined the question of metal goods moving by pre-contact trade around the northern Pacific Rim (Keddie 1990). This process may account for some of the metal assumed to be of a shipwreck origin – but I see this trade as an additional source of metal materials to those from Japanese shipwrecks and, after the mid 16th century, from European sources.

I will focus here on the question of the extent and frequency of 19th century shipwrecks – both manned and unmanned. I will not deal here with the few cases of motorized vessels that have come ashore in the 20th century.

Although Japanese shipwrecks may have been frequent, the uncritical examination of historic records has resulted in a highly exaggerated account that clearly biases the documentation in favor of the frequency of both manned and unmanned shipwrecks on the eastern Pacific coast. Most of the early accounts indicate that the Japanese shipwrecks were closer to the Asian coast than to that of North America, or turned toward the Polynesian Islands after heading west across the ocean. Several shipwreck lists contain duplications of the same event; did not happen where they were said to occur; or in a few cases were confused with Spanish or possibly English shipwrecks (Cook 1973) and one Russian shipwreck (Owens 1985).

Numerous articles have been written by both historians and popular writers pertaining to the wrecking of 19th century Japanese vessels on the shores of British Columbia. None of these stories are true. They are all based on misinformation surrounding events of two shipwrecks off the coast of the states of Washington and California and others that occurred off the coast of Japan. There were, however, recorded 19th century visits by Japanese rescued from wrecks off the coast of Japan.

Before examining the British Columbia record I think it is important to provide an overview of the pre 19th century situation regarding relations between Japan and the Spanish Colonies of the New World. An understanding of the events of this time will help give us a base from which to judge both current and future evidence regarding the general question of shipwrecks and cultural contact between Japanese and indigenous Northwest Coast cultures.

THE MANILA/JAPAN NEW WORLD CONNECTION

For 244 years between 1565 and 1815 the trade between South-East Asia and Mexico involved nearly a thousand ship voyages, some of which made landings in present-day California and may have landed further north along the Northwest Coast. Out of these numerous voyages the galleon San Francisco Xavier, commanded by Santiago Zabalburu was the only ship that failed to reach port on its return voyage from Manila in 1705. Others were wrecked but accounted for on the western side of the Pacific (Cook 1973; Cutter 1989). This 1705, wreck was most likely that reported as occurring in Nehelem Bay Oregon and in the past mistakenly assumed to be a Japanese wreck on the bases of the finding of large quantities of bees wax along the shore in this general area. Beeswax has been documented as cargo on Spanish ships coming from Manila as well as on Japanese vessels. Many survivors of this wreck lived on shore and some intermarried with local aboriginal populations (Cook 1973; Keddie 1990 and references).

A large quantity of iron and other European goods from this wreck would have likely been traded to the north. Other pre-contact Northwest Coast iron sources are likely from further European landings and wrecks to the south of this area. The latter would include: the abandoning in 1542, of a vessel of Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo in the San Diego area; the 1579, visit of Francis Drake to unknown locations between Alaska and the San Francisco bay area (Suden 1990); the 1588 visit of Cavendish with his ship Content which disappeared on is way north; the 1587 visit of Pedro de Unamuno to Morro Bay California; and the 1595 running aground of Sebastian Rodriguez de Ceremeno’s ship the San Agustin in Drakes Bay on the return trip from Manila (Heizer 1941; Cutter 1989).

Further research of European documents is necessary to determine if other landings were made along the Northwest Coast. Regular landings might be suggested in the letter of Fray Andres de Aguirre writing to the Archbishop of Mexico in 1584. Andres makes a request for: “the exploration of that coast and region beyond the forty-first degree of latitude, is of great importance and very necessary in connection with the return voyage of vessels from the Philippines and all parts of the west, … Although the ships which come every year from the west to the port of Acapulco make a landfall on that coast and sail within sight of it for more than five hundred leagues [about 1500 miles or 2400 km], to the present time it is not known what harbors or places where repairs can be made it has.”

The Manila galleons usually departed from Acapulco each January and sailed due west near the 13th parallel pushed by steady trade winds. They changed course to reach the Mariana Islands and then headed above 35 degrees N. latitude to get to the Philippines before the contrary winds of the autumn monsoon.

In 1565 the navigator Andre de Urdaneta in the San Pablo and shortly after Miguel Lopez de Legazpi in the San Lucas sailed north from the Philippines parallel to the Japanese coast. They were swept in the Kurosio current and found the westerlies to carry them back across the ocean at about 37 degrees north. This eastern route to Acapulco beyond the East to West trade winds was subsequently used by hundreds of ships returning to Mexico. The first landfall was often near Cape Mendocino in Northern California (Mountfield 1997). It is not known if any of these ships made emergency landings for water, food or repairs to the north of California. If any loss or transfer of goods to aboriginal peoples along the Northern Coast did occur these items could include Chinese artifacts, which were being shipped to Acapulco by 1573, and iron from Spanish ships that was produced in China and Japan.

The Spanish may have found out about this northern route from the Japanese traders whom they met in the Philippines. Maps of the route to North America may have become available to the Japanese near this time as some of them traveled to Mexico. In 1579 Francis Drake obtained maps for the voyage from Panama to the Philippines from a captured Spanish frigate (Irving 1927 p. 178-179). On November 17, 1587 Thomas Cavendish captured two Japanese from the Spanish ship Santa Anna at 23 3/4 degrees N.: “He tooke out of the great shippe two young lads borne in Japan, which could both wright and reade their own language, the eldest being about 20 years olde was named Christopher, the other was called Cosmus, about 17 yeeres of age, both of very good capacitie” (Irving 1927, p. 216).

In 1608 there were fifteen thousand Japanese residing in the Philippines, “some of whom were probably employed in the Crews of the galleons, eight of which came to

Acapulco each year” (Nuttall 1906, p. 46). Another source of information for the Japanese came after the arrival of the Portuguese in 1543. By 1571 the Portuguese claimed 30,000 Japanese converts to Christianity and 150,000 by 1581 (Smith 1964).

Brooks’s (1876) first account on his shipwreck list of 60 cases refers to Bancroft’s mention of “several Japanese vessels reported in some of the Spanish-American ports on the Pacific. In 1617, a Japanese junk belonging to Magome was at Acapulco.” Brooks seemed to be unaware that intentional voyages were made to Spanish ports during the Manila trade period. In 1598, the Shogun Ieyasu took the first steps towards establishing official relations with Mexico (56 years after the first Portuguese trading vessels visited Japan) by writing to the Spanish Governor of the Philippines. This was an attempt to bypass Manila and open direct trade with Mexico.

The Japanese authorities were well aware of the coast of North America in 1600 as William Adams, one of two Englishmen shipwrecked from a Dutch vessel on April 19 of that year was teaching Geography to the Emperor (Nuttall 1906). Under the guidance of William Adams, the Japanese learned to build ships in the European manner, and undertook voyages to foreign lands – including Spain in 1582(Saito 1912:157).

On August 1, 1610 “twenty three Japanese merchants, who were under the leadership of two noblemen named Tanaka Shosake and Shuya Ryusai accompanied the Spanish to Mexico City where they arrived towards the end of the year”. Vivero, the retiring viceroy of the Philippines introduced them to Don Luis de Velasco the second viceroy of Mexico. A Spanish Ambassador was sent from New Spain to Japan on March 22, 1611 with a Japanese who had been given the name Don Francisco de Velasco and 22 Japanese merchants. They arrived June 10, 1611 and returned to Japan in 1612 Nuttall 1906).

On October 26, 1613 a Japanese built trading vessel, with Spanish as passengers, was sent to Mexico for Masumare, the Japanese Lord of Oxo. It Arrived in Zacatulu Mexico January 22, 1614. The two co-ambassadors in charge of the ship were a nobleman Hasekura Rokuyeman and Friar Luis Sotelo “with a suite of one hundred and eighty Japanese, including sixty Samurai and several merchants. They were provided with letters not only to the Viceroy of Mexico, but also to the King of Spain and to Pope Paul V” (Nutall 1906, p. 40). Part of the embassy stayed in Mexico and the rest went to Spain and to Rome before returning in 1620.

Mercantile relations between Japan and Mexico continued until 1636 when they were brought to an end in part by the foreigner exclusions edict of 1624 and finally by the massacre of Japanese Christian traders in 1637-38.

The Japanese government forbade the construction of deep sea going vessels based on a European design or enlarging the scale of traditional vessels. It has been suggested that this law may have had the effect of increasing the number of disabled ships causing an increase in the number of wrecks that may have drifted across the Pacific Ocean (Brooks 1876). However, the traditional smaller trading and fishing boats continued to be made and would be lost at sea at the same rate as they had in previous centuries before European contact.

The English, French and Dutch continued to prey on the Spanish ships. As late as 1762, the British Commodore George Anson seized a Spanish galleon returning from Manila (Williams 1999).

False Accounts of Shipwrecks on the Coast of British Columbia?

THE EVENT OF 1858

The first known Japanese visitors to British Columbia were a group of twelve men who came to Esquimalt Harbour in 1858. They included the captain, mate and ten seamen being returned to Japan from San Francisco. The men were rescued from a disabled junk 1,600 miles from the coast of Japan where they had been floating helplessly at sea for about five months. The British ship Caribbean, under Captain Winchester, arrived with the men in San Francisco on June 7, 1858. Later in the year Captain Winchester stopped in Victoria on his way to China. The Japanese were transferred to a British war vessel off Japan and landed safely at a Japanese port (Brooks 1964:14).

On March 5, 1859 the Victoria Gazette printed a story from the China Mail of January 6, 1859. It reported that: “The Shipwrecked Japanese Reach Home at Last – About six weeks ago Captain Brooker of the Inflexible, went up to Japan with twelve shipwrecked Japanese, who had been picked up at sea by Captain Winchester, of the Caribbean, taken to California, and then brought over to HongKong that they might be sent back to their own country. Captain Brooker handed over the Japanese to the Government of Nagasaki, and received in return a handsome acknowledgement in the shape of a Japanese table and some velvet as a present for the Admiral and a similar present for the Governor of Hong Kong”.

Captain Wilson mistakenly reports that this vessel was wrecked off Vancouver Island: “as late as 1858 a Japanese vessel was found waterlogged some 200 miles off the coast of Vancouver Island and the crew brought into Esquimalt” (Wilson 1866:275). Joseph Mackay, of the Hudson’s Bay Company, also presents information which mistakenly confuses this 1858 case with an 1834 wreck off the coast of Washington (to be discussed later) and an 1880 visit of a Japanese training ship: “The last wreck of this kind occurred in 1858, when the ‘Caribbean’ an English vessel from San Francisco, consigned to the Hudson’s Bay Company, and laden with provisions, picked up the Japanese crew of a water-logged junk off the coast near Gray’s Harbour. The crew, seven in number, were, at Esquimalt Harbour, made to stand in line with Haidah crew of a canoe on the quarter-deck of the Caribbean, and as they were all costumed alike, there did not appear to be any physical difference between the members of the two races under examination. The Haidahs may be the descendants of Japanese shipwrecked sailors and women of the so-called Tlinkeet race inhabiting Alaska” (Mackay 1899:75). The comparison of Japanese and native peoples referred to here by Mackay is a second hand reminiscence of an event that actually occurred in 1880. Mackay’s statement is in fact a compilation of three separate events. Scholefield (1914:13-14) also mistakes the 1834 wreck as one that occurred in the 1850s).

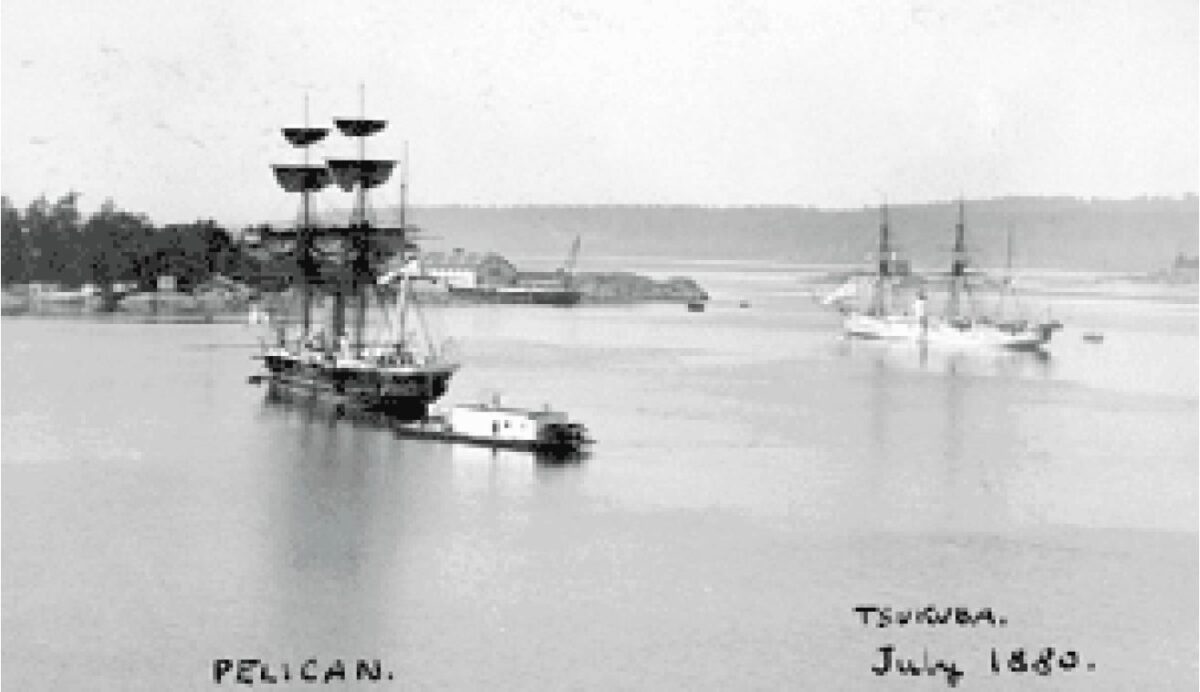

THE EVENT OF 1880

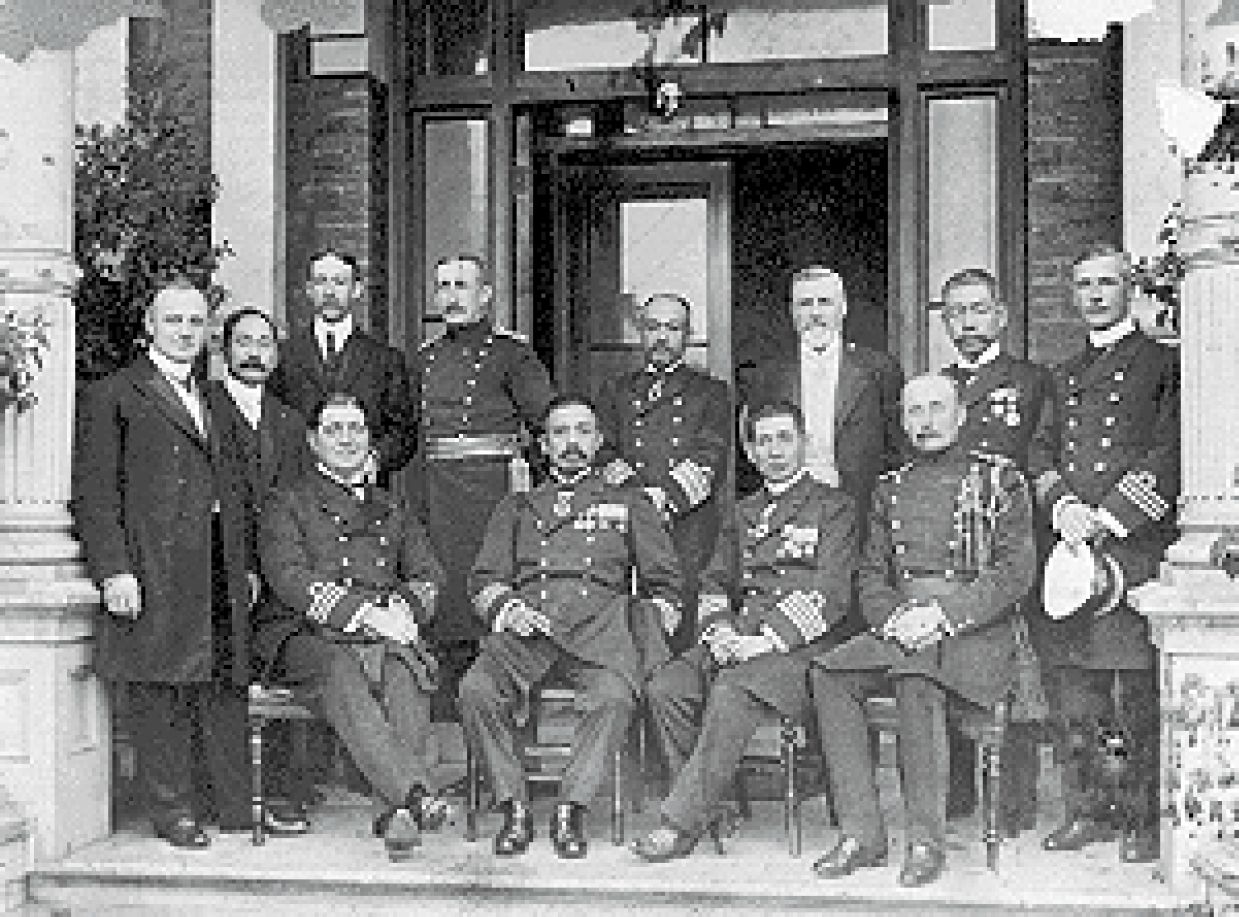

The second visit of Japanese to British Columbia was on June 11, 1880 when the Imperial Japanese naval training vessel Tsukuba 10 with a crew of 338 men and boys and three English advisors visited Esquimalt harbour for three weeks. As reported in the Colonist that day, this vessel was formerly the H. M. corvette Malacca that had visited Esquimalt in 1866 under Captain Oldfield (see Colonist June 22, 1880).

In 1892 Judge Mathew Begbie wrote to Joseph Mackay in response to a letter from the British Consulate in Yokohama inquiring about “information that may throw light on the Ethnological connection between the Japanese and the indigenous races here”. Begbie refers to the 1880 visit of the Japanese training vessel and the viewing of theatrical performances by the sailors on board the ship and how everyone was struck by the similarity between the Japanese “in native costume” and the local native population (Begbie 1892; Colonist June 22, 1880).

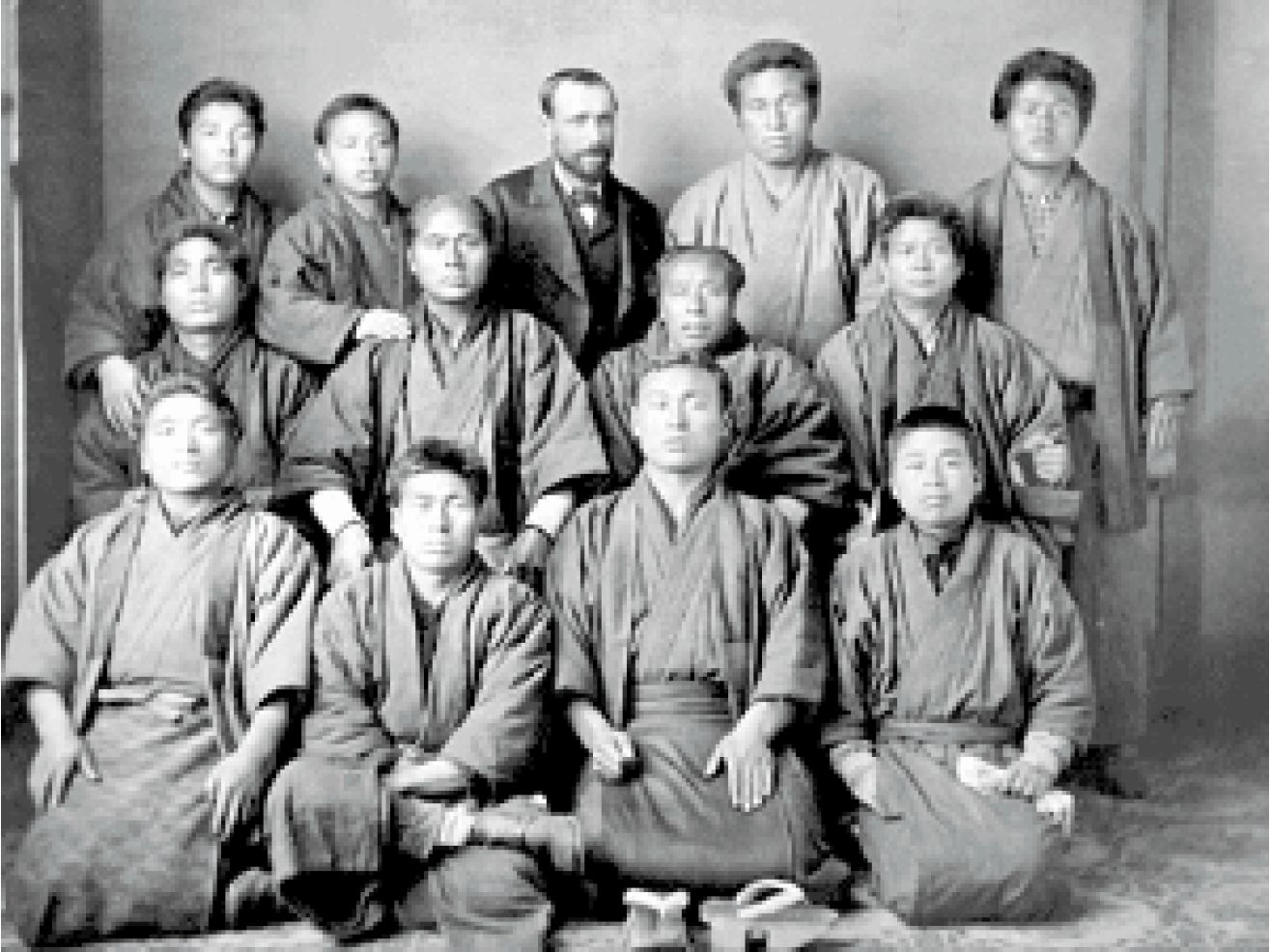

THE EVENT OF 1883

In 1883 another incident occurred whereby Japanese fishermen were wrecked off the coast of Japan, brought first to the United States, and then, on the journey home, were brought to Victoria. On April 11, 1883 the Victoria Colonist reported: “Adrift – Picked up at Sea and Brought to Victoria – The barque Tiber [Tiger], Captain Newby, just arrived in the Royal Roads, reports that one night when about 200 miles off the Loo Choo islands. A cry was heard by the lookout, … As far as he could make out they had been eighty days on short allowance, drifting”. Another short note stated that the shipwrecked men would come ashore on April 12. On April 13 the Colonist states: “The Ship wrecked Japs – The twelve ship wrecked Japanese are still on board the barque Tiger. Captain Newby, who had secured them for forty days, yesterday brought the captain and mate to the office of Findlay, Durham & Brodie, where Mr. Gabrielle, who is an accomplished linguist, conversed with the poor fellows and ascertained that the vessel in what they were cast away was carried from a small

harbor near Hakodadi about four days sail. When Captain Newby took them off they had 120 days at sea in a dismasted hulk the cargo of fish”.

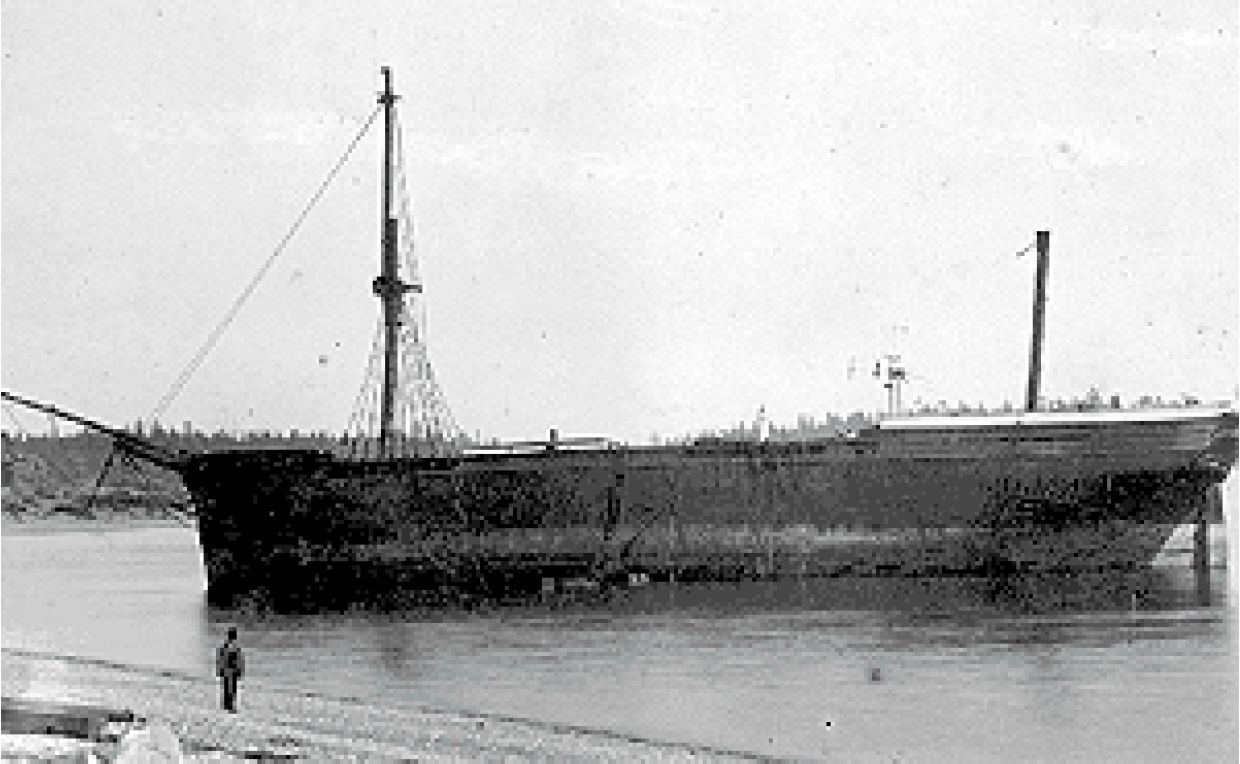

On April 17 the Colonist reports that while waiting in Parry Bay, a storm damaged and grounded the barque Tiger between the Fisgard lighthouse and the entrance to Esquimalt Lagoon.

THE EVENT OF 1815

Many of the confusing references to a supposed shipwreck off the Queen Charlotte Islands had their source in an article written in 1839 by Alexander Forbes who described the following event:

In the year 1813, the British brig Forrester, bound from London to the River Columbia, and commanded by Mr. John Jennings, fell in with a Japanese junk of about 700 tons burden, 150 miles off the north?west coast of America, and abreast of Queen Charlotte’s Island, about 49o of north latitude. There were only three persons alive on board, one of whom was the captain. By the best accounts Captain Jennings could get from them, they had been tossing about at sea for nearly eighteen months; they had been twice in sight of the land of America, and driven off. Some beans still remained, on which they had been maintaining themselves, and they had caught rain?water for their drink.”

In 1876 Charles Brooks refers to the Forbes article without mentioning the “Queen Charlotte’s Island”. Like Forbes he mentions the 49o north latitude but adds the “longitude 128 W.” as the locations of the wreck, which is marked on his map as a location off central Vancouver Island. He also adds that 32 people died of hunger.

The location of the wreck given by Brooks would place the vessel off the West Coast of Vancouver Island about 72 km from Ucluelet. Forbes may have been confusing

Vancouver Island with the Queen Charlottes or may have meant the Queen Charlottes but was guessing at the “about 49o of north latitude”. Brooks, assuming the reference to be off Vancouver Island, approximated the “Longitude 128o W” to be the location “150 miles off shore”.

In fact, this shipwreck occurred “about 300 miles W. S. W. from Point Conception”, California. A written account of this voyage was published in Japanese as told by the shipwrecked sailors themselves. Plummer (1984:117-126) documents this story. The Brig Forester under Captain John Jennings and owned by the American John Jacob Astor, sailed from London in 1813. Due to a mutiny Jennings relinquished command of the ship to William J. Pigot after it reached Honolulu. Pigot was wintering in California and later wrote a letter about the incident on January 7, 1816. Pigot was returning from Cape San Lucas California when he fell in with the Japanese wreck, the Tokujo-maru, on March 24, 1815. It had been drifting for 18 months and had 3 survivors of a crew of 14. The location would be about 470 miles west of the coast of Northern Mexico.

The sailing master of the Brig Forester was Alexander Adams who later related that the wreck was seen “the 24th of March, 1815, at sea near the Coast of California in latitude 32o 45′ North and longitude 126o 57′ West” (Davidson 1869). Brooks documents this report (his number 10) as a separate wreck from that of 1813 (his number 11) but it is clearly the same one. Brooks appears to have extracted this report from Davis (1872:355) who quotes Forbes. As Dall (1886) points out, it is Horace Davis’s paper to which “Brooks is indebted for many of his facts”.

These Japanese survivors did not reach the shores of North America. They were taken from the disabled ship to the Russian settlement of Sitka Alaska. Whether their abandoned ship reached shore or sank at sea is unknown.

The placing of these shipwrecked sailors at Sitka appears to have led to another false claim of a Japanese shipwreck near Sitka [see Brooks, 1876, #8 and Davis 1872b:355]. The men were stationed for the winter on an Island in Sitka harbor that became known as Japonski Island. Later writers assumed the Japanese were shipwrecked on this Island. For example, Schwatka, who was in the area in 1878, stated: “On one of the large islands in Sitka harbour, called Japanese Island, an Old Niphon junk was cast, early in the present century, and her small crew of Japanese were rescued by the Russians” (1894:31).

Washington State – The 1834 Wreck of the Hojun-Maru

The one legitimate northwest coast shipwreck that has caused much confusion in the literature and has lead to the placing of shipwrecks off the coast of British Columbia is the wreck of the Hojun-maru near Point Grenville, south of Cape Flattery on the Olympic Peninsula, in the state of Washington. Drury (1945), Kohl (1982) and Plummer (1984) have documented the case of the Hojun-maru in part, in more recent times. Due to the confusion in the literature regarding this wreck I will deal here in more detail with some of the early references on the topic.

The Hojun-maru left the Japanese port of Toba on October 11, 1832 carrying a load of rice and some special gifts of ceramics as the Owari clan’s tribute to the Shogun. The ship was disabled in a typhoon and carried across the Pacific by the Kuroshio Current. It landed on shore between about February to May 1834 with three survivors – Iwakichi 28, Kyukichi 15 and Otokichi 14. [Recorded as passengers to England on the ship Eagle on November 15, 1834 as Youakeeche, Qukeeche and Otakeeche (HBCA 1834). The survivors were taken as slaves by the local native peoples until personnel of the Hudson’s Bay Company rescued them.

An entry in the Fort Nisqually journal for June 9, 1834 states: “About 2 P.M., we heard a couple of cannon shot; soon after I started in a canoe with six men, and went on board the Llama, with the pleasure of taking tea with McNeil, who pointed out two Chinese he picked up from the natives near Cape Flattery, where a vessel of that nation had been wrecked not long since. There is one still amongst the Indians, inland, but a promise was made of getting the poor fellow on the Coast by the time the Llama gets there.” (Bagley, 1915:16). As Bagley points out: “As a matter of fact, these were Japanese, and the third man was rescued later.” (Bagley, 1915:16).

John McLoughlin mentions this wreck November 18, 1834 in a letter to Hudson’s Bay Company officials: “A Japanese junk was wrecked last winter in the vicinity of Cape Flattery and out of the crew of fourteen men only three were saved and redeemed from the Indians by Captain McNeill on his voyage this summer to Fort Langley. The Japanese entrusted the letter No.- to the natives and it was forwarded from tribe to tribe until it came to us. I also send a piece of carved wood with Chinese characters on it, and if I understand the Japanese correctly it is the name of the vessel, that she was from Yahougari and bound to Yiddo the Capital of Japan with a cargo of rice nankeens and porcelain ware. They were first driven from their course by a Typhoon and subsequently a sea unshipped their rudder or broke their rudder irons, when the vessel became unmanageable, and that they were about a year from the date they left their home when they were wrecked, at which time they had plenty of rice and water yet on board but that a sickness had broke out among the crew which carried off all except these three. A little after the vessel grounded and before the natives could get anything worth while out of her a storm arose and broke her up” (McLoughlin 1834). The next day McLoughlin wrote “N. B. I have opened my letter to inform you that I send the compass the Japanese had on board the Junk lost at Cape Flattery, their honors may consider it a curiosity” (McLoughlin 1834a).

One of the early accounts of this incident was a personal observation in 1834 by Alexander Caulfield Anderson. Anderson intercepted an aboriginal group at Cape Disappointment at the mouth of the Columbia River after they had acquired goods from the Hojun-maru. Anderson notes that the “Indians boarded our vessel and produced a map with some writing in Japanese characters; a string of the perforated copper coins of that country; and other convincing proofs of a shipwreck It was south of Cape Flattery (at Queen-ha-ilth I believe)” (Anderson, 1863).

Alexander C. Anderson refers again to the Hojun-maru wreck in 1877 after commenting on his belief that native peoples of the Northwest Coast:

“originate from the westward – from Japan, the Kuriles, and elsewhere. There are many points of physical resemblance, with probably remote traces of customs, which indicate the origin of some of them, at least, from Japan. Whether the immigration in the remote past has been voluntary or fortuitous, it is of course vain to conjecture; but the possibility of the latter supposition has been convincingly established, even within the limit of my own experience. For in 1834, in consequence of Indian rumors, which had reached the Columbia River during the preceding winter, a vessel was dispatched from Fort Vancouver to Queen-ha-ilth, south of Cape Flattery, to enquire into the circumstances of a reported wreck. The late Captain McNeill, commander, on arriving there, found the remnants of a Japanese junk, purchased from the natives a quantity of pottery and other articles that had formed portions of her cargo. He likewise brought away three Japanese, the survivors of a crew originally consisting, as we understood, of forty; the rest having perished at sea of hunger.”

The first published misinformation about this shipwreck was perpetuated in 1837 by Washington Irving in an extract of a letter he had “received lately” from Captain Wyeth. Irving mentions that the letter “may be interesting, as throwing light upon the questions as to the manner in which America has been peopled” and quotes Wyeth as follows:

“In the winter of 1833, a Japanese junk was wrecked on the north-west coast, in the neighborhood of Queen Charlotte’s Island, and all but two of the crew, then much reduced by starvation and disease, during a long drift across the Pacific, were killed by the natives? The two fell into the hands of the Hudson’s Bay Company and were sent to England. I saw them on my arrival at Vancouver in 1834.” (Irving 1837:246).

Captain Belcher quoted Irving’s reference later that same year. In 1837 while visiting Fort Vancouver Captain Belcher received from the officers of the Hudson’s Bay several articles of Japanese porcelain, which had been washed on shore from the Hojun-maru. Belcher notes that Mr. Birnie, who was at Fort Vancouver when the wreck occurred, stated that Wyeth was wrong. The wreck did not occur in the Queen Charlottes, but south of Cape Flattery (Pierce and Winslow 1979:68-69).

In another letter written later by Wyeth on May 1, 1848 he does not give the wreck location as being on the Queen Charlottes: “In the winter of 1833 I saw two Japanese who had been wrecked in a junk near the entrance to the straits of de Fuca; and if they had been dressed in the same manner, and placed with the Chinook slaves whose heads are not flattened, I could not have discovered the difference” (Schoolcraft 1851:217).

Wyeth’s initial confusion, or that of someone quoting him as to the location of the wreck, may have been a result of confusing the local native name of the trading village at the mouth of the Quinalt River, referred to at the time as “Queen-al-hilth”, with the Queen Charlotte Islands Dall (1877:240) again published Wyeth’s earlier mistaken information.

Charles Wilkes collected second hand information on the Hyogun Maru wreck in 1841. He refers to the wreck of a junk in 1833 “near Point Grenville”. The Hudson’s Bay Company personnel “received a drawing on a piece of China-paper, in which were depicted three shipwrecked persons, with the junk on the rocks, and the Indians engaged in plundering.” Japanese porcelain was obtained from native people and was in the possession of Mr. Burnie of the Hudson’s Bay Company at Astoria (Wilkes, 1845:295-296).

Rickard (1939:47), after quoting extensively from Brooks and Davis, continues the misrepresentation of the Hogun-maru case by the statement: “Another story says that in 1833 also several Japanese were purchased from the Haidas, at Fort Simpson, and given their freedom.” This story came from a 1929 publication of Marius Barbeau (1929:22 and 1964:831) who repeated Brooks mistake of placing the Hyogun Maru wreck on the Queen Charlottes, and after reading of a rescue by the Hudson’s Bay company must have assumed that it was Port Simpson where the survivors were taken to rather than Fort Vancouver.

Over the years numerous authors have repeated this mistake and have perpetuated the myth of the three Japanese shipwreck survivors landing on the Queen Charlotte Islands. More recently, Takata relied on some of these earlier inaccurate sources in stating: “This is the earliest recorded landing of the Japanese on what was to become Canadian soil. The date was 1833” (Takata, 1983:12).

NOTE #1

(1) “Queen Hithe” is shown on a chart prepared by Lieutenant Roberts under the direction of Captain Cook (Roberts 1784). On April 3, 1814 Alexander Henry mentions in his dairy that a man returning from a trip to Gray’s Harbor reported two ships [one of these is the Brig Forester mentioned earlier] “trading at Queenhithe”. The editor Elliott Coues notes: “This appears to stand for Queniutt, Quinaiutt, Quiniault, or Quinaielt, name of an Indian tribe who lived on the coast of Washington a little N. of Gray’s harbor. A large Indian reservation of this name now occupies the N. W. part of Chehalis Co. Wash., with a lake, a river, and a place on the coast, all called by the same name; and this latter place, between Cape Elizabeth and Point Greenville, seems to be what Henry means by “Queenhithe.” (Coues 1897:864). Horr notes that it was the neighbors of the Quinalt, the Quileute tribe, that had their name corrupted by Euro-Americans to “Kwenaiwitl” and to “Queen Nythe” (Horr, 1974, p.209). According to Olson, however, it was the Quinault (the cultural group south of the Quileute) whose name is a corruption of Kwi’nail which was once the name of the major village at the south entrance of the Quinault River (Olson, 1936, p.11).

Concluding Remarks

Critical reviews of Japanese shipwreck accounts have not been undertaken. Casual acceptance of these accounts has resulted in an exaggerated impression of their frequency.

The earliest documented visit by Japanese to British Columbia is in 1858. Others visited in 1880 and 1883. None of these individuals were from ships wrecked on the coast of British Columbia.

There is presently no evidence of the occurrence of 19th century Japanese shipwrecks anywhere along the coast of British Columbia. All of the written accounts, making such claims, are based on inaccurate information.

In spite of poorly documented cases there is evidence of one Japanese shipwreck with survivors that landed near Point Grenville in Washington State in the first few months of 1834, and another off the coast of southern California in 1815, both with three survivors each. Brooks and Davis list another four potential cases off the northern Mexico/U.S. border area with one of these having 3 survivors. Other cases are vaguely defined with no supporting evidence: Brooks’s # 54 “A junk has been reported as stranded on the coast of Alaska”; # 57 “A Japanese wreck was sighted adrift below San Diego”; # 58 “A junk was wrecked at Nootka Sound”. None of the latter can be taken seriously without more information.

To the north there is substantial documentation for wrecks on the Kamchatcha Peninsula and several wrecks on the Aleutian Islands between the mid 1700s and 1871 (Muller 1761; Burney 1819; Black 1983).

It is highly probable that shipwrecks did occur on the coast of British Columbia before the twentieth century but these were never documented. The evidence for such wrecks and any influence that survivors may have had on local native cultures may need to await the research of archaeologists.

How to recognize and interpret potential evidence of early contact with Japanese cultures will be a difficult task. Many archaeologists working in British Columbia have little experience in the kind of Historic Archaeology necessary to examine this topic. Archaeologists would tend to assume than iron goods in an archaeological site represent a time-period after the 1760s, unless the item is of a type that would be something of obvious Japanese origin and found in a deeper undisturbed layer with aboriginal materials.

A database for the identification and comparison of metal artifacts has not been developed for the north Pacific Rim. Determining the cultural context of metal dating to after the 1400s will prove difficult in light of the fact that iron of Japanese and Chinese origin was used in the building of many Spanish ships.

The archaeological record for most areas of the coast of British Columbia remains an unexamined landscape. Evidence of non-indigenous materials will undoubtedly be found to again raise the question of outside cultural influences and the role they played in local indigenous cultures.

Sources Cited

Ames, Kenneth (1998) Chinook Cellars. Ethnohistory and Archaeology on the Northwest Coast: Papers in Honour of Donald H. Mitchell. Presented at the Canadian Archaeological Association, Victoria, B.C.

Ames, Kenneth and Herbert D.G. Maschner. (1999) Peoples of the Northwest Coast. Their Archaeology and Prehistory. Thames and Hudson Ltd., London.

Anderson, Alexander C. (1863). Notes on the Indian Tribes of British North America, and the Northwest Coast. The Historical Magazine, New York Historical Society 7(3):73-81.

Anderson, Alexander C. (1877). Indians. In: Guide to the Province of British Columbia for 1877-8, pp. 214-221, T.N.Hibben & Co., Victoria.

Anderson, Alexander C. (1872). A Brief Description of the Province of British Columbia, Its Climate and Resources. In: The Dominion of the West, pp.101-2, Victoria, Richard Wolfenden.

Bagley, Clarence B. (1916). “Journal of Occurrences at Nisqually House”, In: Washington Historical Quarterly, 6:16 & 276; 7:62.

Bancroft, Hubert H. (1884). History of the Northwest Coast, Vol. 2:533, San Francisco.

Barbeau Marius (1964). Totem Poles. Totem Poles According to Location. Bulletin No. 119, Vol. II, National Museum of Canada, Anthropological Series No. 30.

Barbeau, Marius (1947). Alaska Beckons. Caxton Printers, Ltd, Caldwell, Idaho, The Macmillan Co. of Canada, 1947.

Barbeau, Marius (1929). Totem Poles of the Gitksan, Upper Skeena River, British Columbia. Canada Department of Mines. National Museum of Canada, Bulletin 61, Anthropological series No. 12, Ottawa.

Beattie, Owen. Brian Apland, Erik W. Blake, James A. Cosgrove, Sarah Gaunt, Sheila Greer, Alexander P. Mackie, Kjerstin E. Mackie, Dan Straathof, Valerie Thorp and Peter M. Troffe. (2000). The Kwaday Dan Ts’inchi Discovery from a Glacier in British Columbia. Canadian Journal of Archaeology, 24:1-2:129-147.

Begbie, Mathew. (1892). Letter to Joseph Mackay, Dec. 27, BCARS Additional Manuscript 1917, vol. 1, file 3.

Black, Lydia. (1983). Record of Maritime Disasters in Russian America, Part One: 1741-1799. In: Proceedings of the Alaskan Marine Archeology Workshop. May 17-19, 1983, Sitka, Alaska. (ed) Steve J. Langdon,pp. 43-58, University of Alaska, Fairbanks.

Brooks, Charles W. (1964) [1876]. Japanese wrecks stranded and picked up adrift in the North Pacific Ocean. (Paper presented at the California Academy of Sciences), Fairfield, Washington: Ye Galleon Press.

Burney, James. (1819). A Chronological History of the North-Eastern Voyages of Discovery; and of the Early eastern Navigations of the Russians. Luke Hansard & Sons, London.

Coues, Elliott (1897). New Light on the Early History of the Greater Northwest. The Manuscript Journals of Alexander Henry Fur Trader of the Northwest Company and of David Thompson Official Geographer and Explorer of the same Company, 1799 – 1814. Exploration and Adventure among the Indians on the Red, Saskatchewan, Missouri, and Columbia Rivers. Edited with copious and critical commentary by Elliott Coues. Vol. II, The Saskatchewan and Columbia Rivers, New York, Francis P. Harper.

Cutter, Donald C. Early Spanish-Indian Contacts in the Pacific Northeast. 1541-1795. In: Circum-Pacific Prehistory Conference, Seattle, Washington U.S.A. August 1-6, 1989 Reprint Proceedings, pp.18.

Dall, William H. (ed) (1877). Letter from Captain Wyeth. In: Tribes of the Extreme Northwest, Contributions to North American Ethnology, Department of the Interior, United States Geographical Survey of the Rocky Mountain Region, No.1.

Dall, William H. (1886). Alleged Early Chinese Voyages to America. Science (old series) 8(196)402-403.

Davis, Horace (1872a). Records of Japanese Vessels driven upon the Northwest Coast of North America and its outlying Islands. Worcester, Massachusetts.

Davis, Horace (1872b). Japanese Wrecks in American Waters.Overland Monthly, 9:353-360. San Francisco: John Carmany and Co.

Davison, George (1869). Alaska Coast Pilot. United States Coast Survey.

Drury, Clifford M. (1945). Early American Contacts with the Japanese. Pacific Northwest Quarterly, 36:4:319-330.

Forbes, Alexander (1919) [1839]. California. A History of Upper and Lower California From Their First Discovery to the Present Time. San Francisco, California, Thomas C. Russell (reprinted from original ed. pub. by Smith, Elder & Co., London).

Gleeson, Paul F. (1980). Ozette Woodworking Technology. Project Reports 3. Laboratory of Archaeology and History, Washington University, Pullman.

Griffin, George Butler. Ed. Trans. (1891). Letter of Fray Andres de Aguirre to the Lord Archbishop of Mexico, 1584. In: Documents from the Sutra Collection. Publications of the Historical Society of Southern California, Loas Angeles.

HBCA. (1834). Hudson’s Bay Company Archives, Manitoba, Canada, C.7/177, fo.35.

Heizer, Robert F. 1941. Archaeological Evidence of Sebastian Rodriguez Ceremeno’s California Visit in 1595. California Historical Society Quarterly 20 (4):315-328.

Horr, David Agee (editor) (1974). The Quileute Indians of Puget Sound. Indian Claims Commission, Docket No. 155 and 242. In: Coast Salish and Western Washington Indians II, Garland Publishing Inc., New York and London.

Irving, Washington (1837). The Rocky Mountains; or, Scenes, Incidents, and Adventures in the Far West; Digested from the Journal of Captain B. L. E. Bonneville, of the Army of the United States, and illustrated from Various Other Sources. Volume II. Philadelphia, Carey, Lea, and Blanchard.

Irving, William. Ed. (1927). A Selection of the Principal Voyages, Traffiques and Discoveries of the English Nation by Richard Hakluyt 1552-1616. Set Out With Many Embellishments and a Preface, William Heinemann Ltd., London.

Keddie, Grant (1994). B.C’s First Japanese Tourists. Royal British Columbia Discovery, News and Events, 23:2:1-2.

Keddie, Grant (1990). The Question of Asiatic Objects on the North Pacific Coast Of America: Historic or Prehistoric? Contributions to Human History, No.3, Royal British Columbia Museum, Victoria.

Kohl, Stephen W. (1982). Strangers in a Strange Land. Japanese Castaways and the Opening of Japan. Pacific Northwest Quarterly, 73(1)20-28.

McLoughlin, John (1834 and 1834a). McLoughlin’s Fort Vancouver Letters. First Series 1825 – 1838. Archives of British Columbia, Victoria. Manuscript NW 979.5 M165.2, Vol. 1, B223/b/10, fos. 33-7 and B223/b/10, fo. 38d.

Mackay, J. W. (1899). The Indians of British Columbia. A Brief Review of Their Probable Origin, History and Customs. The B. C. Mining Record, Christmas Supplement.

Mountfield, David. (1997). The Pacific, Australia and New Zealand. In: Oxford Atlas of Exploration. Pp. 148 – 171. Edited by Jane Edmonds.

Muller, Gerhard. (1761). Voyages From Asia to America, For Completing the Discoveries of the Northwest Coast of America. To Which is prefixed, A Summary of the Voyages Made by the Russian on the Frozen Sea, In Search of a North East Passage. Translated from the High Dutch. Thomas Jefferys Geographer to his Majesty, London.

Nuttall, Zelia. (1906). The Earliest Historical Relations Between Mexico and Japan. From Original Documents Preserved in Spain and Japan. University of California Publications. American Archaeology and Ethnology, Vol. 4, No.1. Berkley, The University Press.

Olson, Ronald. (1936). The Quinalt Indians. University of Washington Press, Seattle.

Owens, Kenneth N. (1985). The Wreck of the Sv. Nikolai. Two Narratives of the First Russian Expedition to the Oregon Country 1808-1810. Edited with introduction by Kenneth N. Owens, Translated by Alton S. Donnelly, Western Imprints. The Press of the Oregon Historicial Society.

Pierce, R.A. and J. H. Winslow (ed) (1979). H.M.S. Sulphur on the North West and California Coasts 1837 and 1839. Materials for the Study of Alaska History, No. 12. The Limestone Press.

Plummer, Katherine. (1984). The Shogun’s Reluctant Ambassadors. Sea Drifters, Lotus Press, Tokyo, Japan.

Quimby, George I. (1989) Consequences of Early Contacts Between Japanese Castaways and Native Americans: A Hundred Year Old Problem Still With Us. In: Circum-Pacific Prehistory Conference, Session VIII Prehistoric Trans-Pacific Contacts. Seattle, Washington U.S.A. August 1-6, 1989 Reprint Proceedings.

Quimby, George I. (1985). Japanese Wrecks, Iron Tools, and Prehistoric Indians of the Northwest Coast. Artic Anthropology 22(2):7-15.

Quimby, George I. (1948). Culture Contact on the Northwest Coast, 1785-1795, American Anthropologist. N.S. Vol. 50, pp. 247-255.

Rich, E.E. (Editor) (1941). The Letters of John McLoughlin from Fort Vancouver to the Governor and Committee, First Series, 1825-38, p.122, Toronto.

Rickard, T. A. (1939). The Use of Iron and Copper by the Indians of British Columbia, British Columbia Historical Quarterly, 3:1:25-50.

Roberts, Luet. Henry. (1784). Chart of the Northwest Coast of America and the Northeast Coast of Asia Explored in the years 1778-79. Published by William Faden, Geographer to the King, July 24, 1784 (2nd edition Jan. 1, 1794), London.

Saito, Hisho. (1912). A History of Japan. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., Ltd, London.

Samuels, Stephen R. and Richard D. Daugherty. (1991). Part I. Introduction to the Ozette Archaeological Project. In: Ozette Archaeological Project Research Reports. Volume 1, House Structure and Floor Midden, edited by Stephan R. Samuels, Reports of Investigations 63, Department of Anthropology, Washington State University, and National Park Service, Pacific Northwest Regional Office, Seattle.

Scholefield, E.O.S. (1914). British Columbia. From the Earliest Times to the Present. Volume 1. The S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, Vancouver.

Schoolcraft, Henry R. (1851). Historical and Statistical Information respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States. Collected and Prepared Under the Direction of the Bureau of Indian Affairs Per Act of Congress of Mar. 3rd 1847. Philadelphia, Lippincott, Grambo & Co.

Schwatka, Frederick. 1894. A Summer in Alaska. A Popular Account of the Travels of an Alaska Exploring Expedition Along the Great Yukon River, From Its Source to its Mouth, in the British North-west Territory, and in the Territory of Alaska, St. Louis, MO, J. W. Henry.

Smith, Bradley. (1964). Japan. A History in Art. Doubleday & Company, Inc., New York.

Sugden, John. (1990). Sir Francis Drake. Simon & Schuster, N. Y.

Takata, Toyo (1983). Nikkei Legacy. The Story of Japanese Canadians from Settlement to Today. NC Press Limited, Toronto.

Tarakanov, Vasilii. (1853). Wreck of Russian American Company Ship St. Nicholas.

In: Golovin, V. M. Descriptions of Remarkable Shipwrecks. Vol. 4. St. Petersburg.

Williams, Glyn. 1999. The Prize of All the Oceans. The Dramatic True Story of Commodore Anson’s Voyage Round the World and How He Seized the Spanish Treasure Galleon, Viking, New York.

Wilson, Captain (1866). Report on the Indian Tribes inhabiting the country in the vicinity of the 49th Parallel of North Latitude. In: Ethnological Society Of London, Transactions, Vol. 6, New Series, Chapter XXIII, pp. 275-332.

Wilkes, Charles (1845). Narrative of the United States Exploring Expedition During the Years 1838, 1839, 1840, 1841 and 1842. Philadelphia: Lea & Blanchard.

Photo Captions

Officers of the Japanese Naval Training Ship Tsukuba Visiting the Esquimalt Naval Base in 1880 (B.C. Archives, A-03129).

The Japanese Naval Training Ship Tsukuba (right) in Esquimalt Harbour in 1880 (B.C. Archives, B-02816).

Japanese crew of shipwrecked fishing junk picked up in the Sea of China and brought to the U.S. They are shown here in Victoria on April 20, 1883, with Captain John Newby of the Barque Tiger. (BC Archives, Maynard Photo, B-08405).

The Barque Tiger that was returning Japanese shipwrecked fishermen was blown ashore near Esquimalt Lagoon in April 1883. (B.C. Archives, C-03693).