2003.

by Grant Keddie

In the municipality of Oak Bay, above the western side of Cadboro Bay, part of the uplands drain through a deep ravine now referred to as Mystic Vale. The creek that flows through this vale, or valley, has never been given a legal name but is referred to locally as Mystic Creek or Hobbs Creek. Mystic Creek flows north of Vista Bay Road and between Bermuda Street and Killarney road to the north of Cadboro Bay road. South of Cadboro Bay road the creek flows on the east side of Killarney road. Recently its south end was diverted east to Sinclair road.

To the west of Killarney road is Mystic Lane. Artificial duck ponds have been created above and below this lane. The area between Killarney road and the hill slope below Hibbens Close receives its surface and underground water supply from some of the uplands west of Mystic vale. House and yard construction projects in the 1930’s and especially the development of the Cadboro Bay Auto court property in the 1940’s disrupted the flow and configuration of two small creeks in this area. Three large ponds were dug in the 1940’s to contain the flow of one of the creeks. Later, landfill and house construction altered this area substantially. The present artificial duck pond along Waring road is a remnant of one of these earlier water control ponds. Water coming out of the slopes to the west of Waring road now comes out of a pipe on to the beach. This may have been a small, at least, intermittent creek in the past.

The location mentioned in First Nations tradition is assumed to refer to a secluded pond along Mystic Creek to the north of Cadboro Bay Road – not one of the later artificially created hillside springs and ponds.

From 1938 until the 1950’s a local resident named William Inglis created a spring on his property between Killarney road and Sinclair Street. He fixed it up as a tourist attraction and mistakenly claimed that it was the original Mystic Spring.

The Written Stories

The story of the Mystic Spring gained prominence through the writings of D.W. Higgins – a newspaper editor and politician whose writings were often riddled with misinformation, suggestions of the supernatural and prone to romanticizing.

Higgins wrote an article in the Colonist newspaper on February 7, 1904 entitled: The Mystic Spring – A Legend of Cadboro Bay. He repeated the story the same year in his book THE MYSTIC SPRING AND OTHER TALES OF WESTERN LIFE.

Higgins contributed to making the Mystic Creek area a sort of lovers Niagara Falls of Victoria by combining the remnants of a First Nations oral tradition with later events of the 1860’s surrounding two young women.

Higgins appears to have obtained his information about the First Nations tradition by general talk in the non-First Nations community and not directly from aboriginal informants. However, he references it in quotes as if to assume it was something that might have been said to James Douglas when he first visited Cadboro bay in 1842.

Higgins refers to a very large and old maple tree on the edge of the creek and how the waters of the spring:

“nestled by the great maple tree were as cool as if they had flowed from a glacier. The Indians were proud of the spring and used its water freely. They said is possessed medicinal properties. They also claimed that it was bewitched. Said one of the chiefs in Chinook jargon to the new arrivals: If a woman should look into the water when the moon is at its full she’ll see reflected in it the face of the man who loves her. If a man looks into the water he will see the woman who loves him and will marry him should he ask her. If a woman is childless this water will give her plenty. The tree is a god. It guards the spirit of the spring, and as long as the tree stands the water will creep to its foot for protection and shade; cut down the tree and the spring will be seen no more”.

A person with Higgins in 1862 is quoted as saying: “The moon must be shining and at its full before you can see the spirit”.

When Higgins first visited Cadboro Bay in 1860 he “reached it by means of a narrow and tortuous trail that led down the side of the hill and terminated at the foot of the big maple. I had heard the legend about the Mystic Spring, and rode out to investigate”.

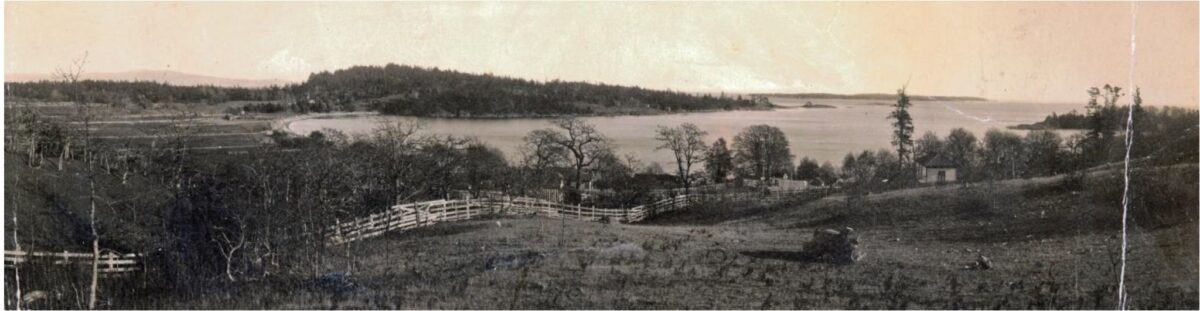

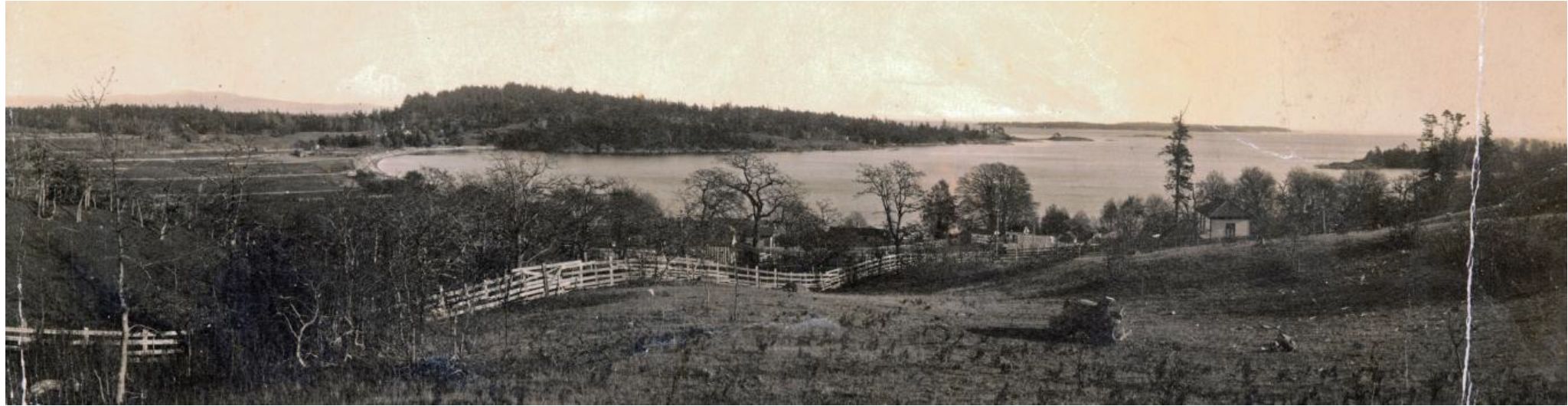

It would appear from this description that the big maple tree was at the foot of a steep hill and therefore in the ravine rather than at the mouth of the creek. Higgins suggests that the big maple tree was cut down about 1888. A photograph taken of Cadboro bay before this time shows Mystic Creek extending across the open fields of Cadboro Bay. No large maple trees are visible in this or later 19th century photographs along the lower creek.

Nellie Shaw (who wrote under the name N. de Bertrand Lugrin) was the daughter of the Colonist editor Charles Lugrin – who came after Higgins editorship. Shaw wrote about a wedding picnic of the nurse of the Crease family that happened at this location in 1860. The picnic was “at Cadboro Bay, near a beautiful spring on the slope of the hill, which bubbled out and ran past a huge maple tree not far from the water”. This location became “a famous picnic place”.

After Higgins’s first visit to Cadboro Bay it:

“became a favorite resort. We put a rude table and a bench at the foot of the maple, which we christened Father Time because of a few sprays of old man’s beard [tree lichen] that hung from a branch. We called the spring Undine, after the famous water sprite of fiction, and nearly every fine Saturday afternoon we formed a small party and rode on Indian ponies to the spot. The fame of Father Time and sweet Undine spread far and wide, and many were the trips made by the lovesick of both sexes to the spring. When the moon was at its full the visitors sought to conjure up their future partners”.

Higgins plays upon an incident in 1862, when a young woman named Annie fainted in the creek. Annie was revived with smelling salts and is quoted as saying that the face she saw was “fearful – the most awful I ever saw. A low-browed, cunning face, deeply lined with wicked thoughts and evil designs, and such awful eyes! He raised his hands to clutch me and I fainted. And he’s to be my future husband! No, I’d sooner die than marry him.”

To this, Higgins adds another incident, which occurred on April 21, 1868, when a women named Julia Booth committed suicide at the same location. Higgins suggests a link to the “spirit” that had “tried to seize” Annie six years earlier.

Another version of the story is presented by Ursula Jupp (1975:27) in her book on the history of the Gordon Head area. She obtained the information from Jack Irvine, a member of pioneer family that came to the Victoria area in 1851. Jack, in turn, had received the information from Ben Evans (1855-1923), who owned property on Cadboro Bay that extended up to the area around Mystic Valley.

Judd notes that Jack’s memoirs include a new and simpler version of the “oft-told story of the haunting of Cadboro Bay’s Mystic Spring”. In Jack’s version the victim was a First Nations girl whose lover had been killed in warfare. Jack indicated that “the spring was the spot where the lovers always met to make love to one another. After he was killed the Indian girl would go to the spot and stand looking into the water and one moonlight night she saw her lover’s face in the water and she threw herself into the spring and was drowned”.

Another opinion as to the location of Mystic Springs was given by Charles H. French, as presented in a newspaper article of 1922 (Editor). The anonymous writer of the article claims that the original Mystic Spring is now under the road just above Loon Bay to the southwest of the Victoria Yacht Club or near the junction of Exeter Street and Beach Drive.

The writer notes that:

“Regarding the Mystic Spring fallacy: At one time there possibly was a spring which gained considerable renown for the alleged magic quality of the water it yielded, but the water hole which now passes for the Mystic Spring has really no connection whatever with the spring of the old-timers and Indians.

That, at any rate, is the contention of Mr. Charles H. French, probably better posted than anyone else in the Province regarding old Indian customs in this district.

Mr. George I, Warren, managing secretary of the committee, of the Chamber of Commerce, wrote to Mr. French recently, asking him to point out the location of the Mystic Spring made famous by the books of the late D.W. Higgins”.

“As a matter of fact, there is not, nor has there ever been, a mystic spring such as you appear to have in mind.” Replied Mr. French, who stated further that it would be unwise, in the interest of accuracy, for the Chamber of Commerce to mark a spot and call it the Mystic Spring.

“The Spring Mr. Higgins had in mind was likely located close to a small house on the beach adjoining the Uplands Farm, owned, I believe, by Mr. Hibben, but the spring of real importance to the Indians and conceded by old Hudson’s Bay men to be the mystic spring was situated in the middle of the asphalt road, just east of the Yacht Club.”

Mr. H. N. Fynn, assistant secretary of the Chamber, visited the spot a few days ago with Mr. French and says that traces of the old spring are still to be found. He dug in the ground only a few feet and found an abundance of fresh water, and he also traced the water-course to the sea by the crude stonework erected by the Indians.”

What exactly Fynn observed in the form of stone structures is uncertain. There were once many hundreds of burial cairns, composed of piles of stones, in the uplands above this location. Some of these existed across the street from the location mentioned by Flynn as late as the 1970s – when I last observed them.

Could Flynn have been mistaken these pulled apart cairns as part of some old water works structure?

An Element of Fact?

In spite of the added fantasies of Higgins and others, given what is known today about aboriginal traditions and beliefs, it is likely that the aboriginal part of the story paraphrased has, at least, some semblance of accuracy. There was a similar pond on top of Smith Hill where First Nations women could go to see the reflection of their future husbands.

In local aboriginal cultures there was no clear distinction between what we perceive today as animate and inanimate objects. There were places on the landscape where spirit beings provided both good and bad influences. These special places were seen in such things as unusual looking rocks, rip tides, whirlpools near waterfalls, isolated ponds and exceptionally old trees. The spirit beings could ascribe powers to those who were ritually clean or create misfortune to those who did not show respect for the place or abused its resources.

The archaeological remains of two large village sites exist at the back of Cadboro bay. One dating to 1800 years ago is located between Waring road and the properties inside the entrance to the Uplands. The other site is 1900 years old and extends from Gyro Park to the east end of the bay. A group of 57 people called the “Samus” and their 70 “followers” lived in a village here in 1839. They were one of the families later known collectively as the Songhees.

Partial Bibliography of Stories and News on The Mystic Spring

Higgins, D.W. 1904. The Mystic Spring and Other Tales of Western Life, Briggs, Toronto, (second edition Broadway Publishing Co. New York, 1908).

Judd, Ursula. 1975. From Cordwood to Campus in Gordon head. 1852-1959. Morris Printing Company Ltd., Victoria, B.C.

Lugrin, Nancy de Bertrand. 1928. Pioneer Women of Vancouver Island, 1843-1866. Edited by John Hosie. The Women’s Canadian Club of Victoria, Vancouver Island.

McKelvie, B.ruce A. 1949. Cadboro Bay’s Mystic Spring is gushing again. The Province, Jan. 29, Magazine Section, p. 8.

Nichols, R. H. 1953. The Mystic Spring Of Cadboro Bay. Its waters allegedly heal sick and foretell future of lovers. The Vancouver Sun, August 8, p. 24.

Paterson, T.W. 1968. Gone, But Not Forgotten. Cadboro Bay’s Mystic Spring. Times Colonist, May 5, Magazine Section, p.10.

Saanich Peninsula & Gulf Island Review. 1962. Mystic Spring mirrored future husbands and wives …and Horror. October 3, p.9.

Smith, Bill. 1978. UVic fails in bid for Mystic Vale property. The Daily Colonist, Feb. 17.

The Daily Colonist. 1978. Cadboro Bay’s lost tribe, July 30, magazine section, p.10.

Times Colonist. 1993. Mystic Vale subdivision plans go to public hearing March 16., Sunday, March 7, Marketplace Section, A3.

Tomlinson, Alice. 1979. Mystic Springs. The Daily Colonist, Nov. 11, magazine section, p. 16.

Victoria Daily Times. 1938. Mystic Spring. Victorian Says Legendary Indian Water Bubbles Out of His Garden., March 26, Magazine section, p.6.