By Grant Keddie 1996.

Part 1: Settlements for Unsettling Times

Over time, glaciers, sea level changes and climate have reshaped our landscape. Around us today is the evidence of how humans have utilized that environment over thousands of years.

By studying types of settlements, archaeologists can get a glimpse of how people related both to the natural world and to other people. In the Victoria area, bounded by Cowichan Head to the north and Metchosin to the west, there are about 100 shoreline shell-midden sites which represent the remains of old aboriginal villages. At least 18 of these have been recorded as defensive sites or villages with large wooden defensive walls and/or defensive ditches.

In spite of the many observations of aboriginal defensive sites along the coast by Europeans from 1774 until the 1860s, authors have persisted in referring to the remains of these as old Spanish forts and claiming they were not here before the coming of Europeans. As we will see in this series of articles, the archaeological remains of these forts show a significant change in the human use of our landscape, beginning before the time of the Norman conquest of England.

The early historic accounts show that these forts were constructed of single and double rows of upright posts sometimes held together by “thin branches interlaced through and through” as well as horizontal boards hung on posts like house boards.

An 1842 map (by Lee Lewes) places an “Indian Fort” with two wooden plank houses at the northeast corner of Cadboro Bay. This village was occupied in 1839 by a group of 127 people called the Samus, one of several extended family groups that later amalgamated on reserves and became known as the Songhees.

In 1843, Jean-Baptiste Bolduc visited this fort:

“Like almost all of the surrounding tribes, this one possesses a stockade fort of about 150 feet square On top of posts in the fort one sees many human heads sculptured and painted in red or black.”

In his writings, Alexander Anderson of the Hudson’s Bay Company describes a voyage down the Fraser River in 1846 that started at the “palisaded fort” of the Tait people near Yale. This account mentions that the Stalo peoples fished in the 3-mile area below the Yale Canyon and then retreated to their “palisaded dwellings.” He further describes: “From point to point as we descend the river, the palisaded villages which I have mentioned appear…” and that due to “local feuds” and to “guard against the incursions of the coast tribes bent on slave-making, the permanent villages are all stockaded.” Even the powerful Cowichans of Vancouver Island had “palisaded villages.”

Anderson also noted that the Cowichan, who under the warrior Tzouhalem attacked Fort Victoria in 1844, had “bullied the other tribes whom they had beaten in war.” Elders have told many stories of how, before the coming of Europeans, the peoples of the American Gulf Islands, Puget Sound and the Olympic Peninsula raided the south end of Vancouver Island and how these people retaliated in kind.

Following the devastating smallpox epidemic of 1782, there had been a period of rapid change in lands surrounding the Strait of Juan de Fuca and the Gulf of Georgia.

The Lekwiltok of Johnstone Strait received guns through trade with peoples on the west coast of Vancouver Island in the 1790s. From the early to mid 1800s, warfare between the Lekwiltok and Salish groups operated on an increasingly larger scale. The Lekwiltok raided far to the south. Salish speaking warriors from as far away as Puget Sound joined forces in retaliatory raids. There were numerous losses on both sides and both sides claimed victories.

When the Hudson’s Bay Company established new fur-trading centres at Fort Langley on the lower Fraser River in 1827 and Fort Nisqually in Puget Sound in 1833, aboriginal alliances began shifting to obtain access to European trade goods. Populations began changing through marriage, migration and warfare. Trading vessels entering the Strait at this time caused further confusion in the trade alliances.

By the late 1830s the Lekwiltok had joined with their northern neighbours and made more frequent raids to Puget Sound and up the Fraser River as far as Yale, causing heavy casualties in both regions. In 1838, a significant alliance was made with the Musqueam, and the Lekwiltok took control over part of the Fort Langley fur trade. Gulf of Georgia groups now found it more profitable to trade their furs northward where they could get twice as much for a beaver skin at Fort Simpson. This change is clearly pointed out in the correspondence of James Douglas:

“The affairs of Fort Langley have not, in all respects, closed so prosperously this season as usual. The Fur trade suffered greatly from the interference of the Colquilts [Lekwiltok]…who have succeeded in opening a friendly intercourse with the Musquiams inhabiting the country at the mouth of Fraser’s river, and have diverted into another channel, the trade formerly derived by Fort Langley, from the Gulf of Georgia. This evil arises from the difference between the Fort Simpson and Fort Langley Fur Tariffs, which in general exceeds 100 per cent.”

In the 1840s, the Lekwiltok began moving south, taking over Comox Salish territory and causing part of the tribes on Vancouver Island to move from their traditional villages in exposed locations to more protected areas up the rivers. Posts were continually maintained to keep the tribes informed of the movements of the Lekwiltok and their allies.

About 1849, the Salish allies caused considerable destruction among several Lekwiltok groups in the Port Neville/Salmon River area to the north of Comox. Around 1850, the combined forces of Cowichan and other Salish warriors defeated the Lekwiltok and their allies in a major battle at Maple Bay, near Duncan.

Many of the raids of the Lekwiltok have been mistakenly attributed to the Haida. It is only in the short period after 1853, when large groups of Haida came to Victoria to trade, that they raided American groups and made a small number of raids on the Cowichan and the Nanaimo. This raiding came to an end with the smallpox epidemic of 1862.

The archaeological evidence for an older pattern of warfare in the Victoria area, the history of its study, the kinds of questions archaeologists are trying to answer and the results of the latest investigations will be described in following issues.

PART 2: Amateur Archaeology Begins

In the Victoria region, a fascination with the archaeological remains of aboriginal “forts” or “trench-embankment sites” started in the 1850s. Many historical documents uncovered in the Provincial Archives show that the sites were well-known by fur traders and early settlers and a keen interest was shown by local members of the Natural History Society (who played a prominent part in founding BC’s provincial museum).

In 1857, Vancouver Island’s first settler, Walter Grant, observed the defensive site above Taylor Beach in Metchosin. He described it as:

…the vestige of some ancient encampment which an antiquary of enthusiastic imagination might call a very proper agger or vallum [rampart of earth], with its…ditch or fossa. The agger is somewhat worn down, but the fossa is clearly discernible some 12 feet in depth and 15 in breadth, extending in an oval from, round three sides the

fourth side is occupied by a steep clay cliff abutting on the sea beach. In 1867, Martha Douglas, the 12-year-old daughter of Governor James Douglas, recorded a visit to her father’s property located in Metchosin mid-way between two defensive sites: the Taylor Beach site and one on the bluff at the west side of Wittie’s Lagoon. We cannot be sure which site Martha refers to in her diary:

Rode all over the property and visited the old Indian fortification. Nobody knows who made it. On asking the Indians about its origin they all say it was made by the old people who inhabited the country before them and they know nothing more about it.

In 1877, George Gibbs reported a site at Dunn’s Nook in Esquimalt Harbour on the estate of Governor Douglas’ sister, Edith Cameron:I noticed a trench, cutting off a small point or rock near the shore,…about six feet deep and eight wide. Governor Douglas informed me that these were not infrequent on the island; that they generally surrounded some defensible place; and that often an escarpment was constructed facing the sea.

Natural History Society members James Deans, Oregon Hastings and Charles Newcombe talked about defensive sites in their lectures and provided information to visiting archaeologists. In 1871, a Victoria Colonist interview with James Deans mentioned the defensive trenches at Finlayson and Clover Points. This newspaper interview was sparked by the excavations of burial cairns by Deans under the instructions of James Richardson of the Geological Survey of Canada, who made a record of the Finlayson Point site. The same year, a quote by Deans was included in a book by historian Herbert Bancroft:

At Beacon Hill…an embankment with a ditch still six feet deep, stretches across on the land side and protects the approach; there are low mounds on the enclosed area, the remnants of ancient dwellings.

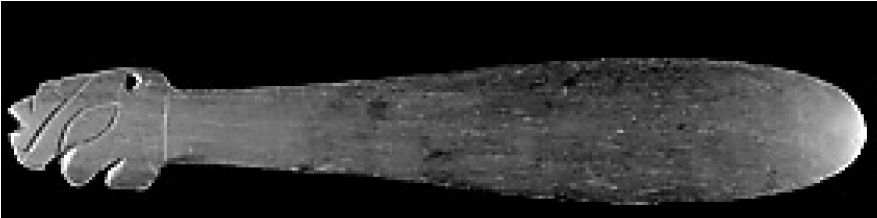

Probably in Uplands Park in Oak Bay. Credit: RBCM collection

In 1891, Deans wrote:

These fortified dwellings are not only found along our coasts, where a point is naturally strong by having its land side protected by a deep moat: but they are also found inland, where they have strengthened themselves behind a bluff or overhanging cliff. Behind all these strong places their burial mounds are found by tens, hundreds and thousands. I have been opening these cairns and studying these facts ever since 1859, so I know pretty well what they are.

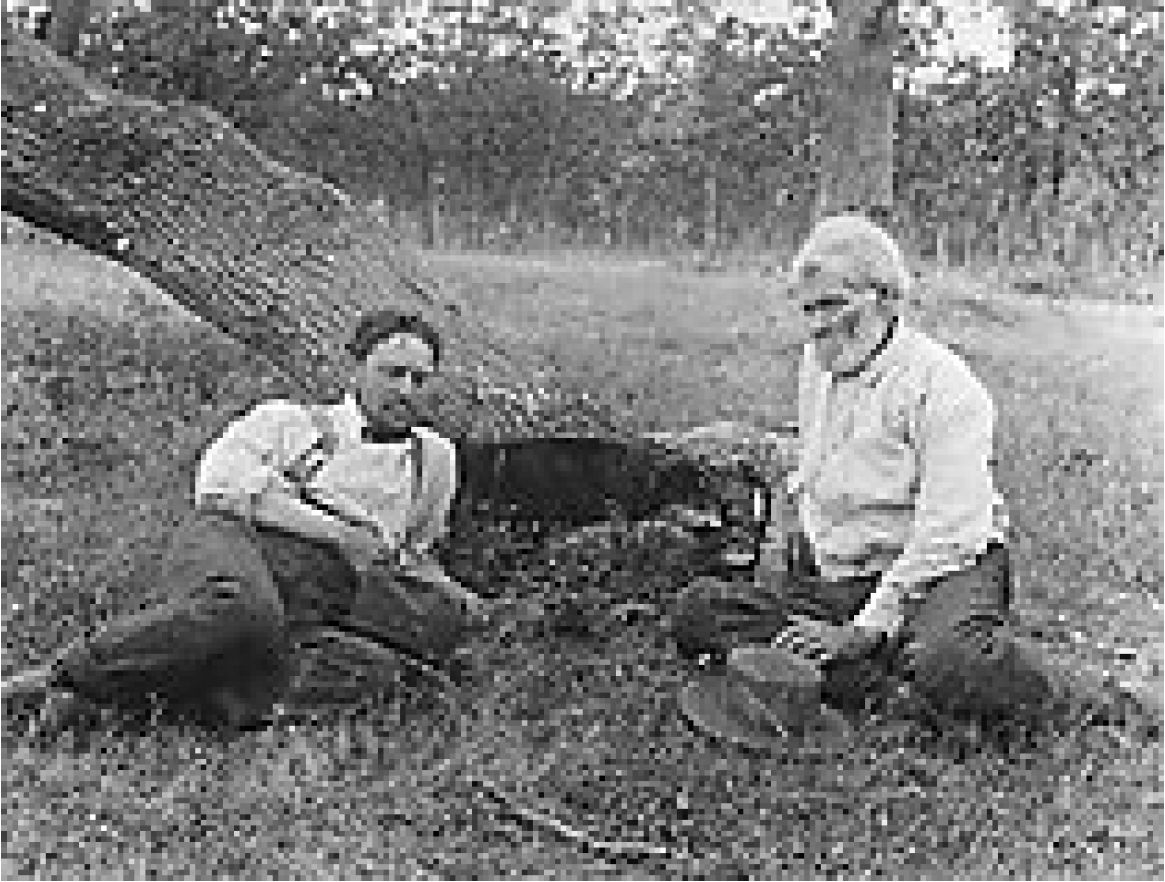

From the 1890s to the 1930s, Dr. Charles Newcombe provided information for Harlan Smith of the American Museum of Natural History and later Dominion archaeologist in the National Museum at Ottawa. Although Smith published information on defensive sites, he only visited one during his work in Victoria. In 1934, William Newcombe developed a list of defensive locations known to his father Charles and himself. Charles Newcombe took the first photographs of two defensive sites in the Cadboro Bay area in 1901. William Newcombe photographed seven others between 1928 and 1935.

Part 3: Modern Archaeologists Collect Evidence

In the Victoria area, there are about 100 shoreline, shell-midden sites which represent the remains of old aboriginal villages. Nineteen of these are defensive sites – villages with wooden palisades and/or defensive ditches.

These unique sites seemed to appear suddenly at a certain time period in the history of local First Peoples. I am interested in understanding the role these kinds of sites played. When and why did aboriginal peoples move to fortified shoreline locations, previously uninhabited? Were existing village sites being fortified at the same time?

The sites of aboriginal defensive villages in the Victoria area have been located by historic observations (see Discovery, Dec. ‘96 and Feb. ‘97) and by modern archaeologists excavating or observing surface features that indicate the presence of deeply dug trenches and embankments. Of the 19 defensive sites, five have remaining observable trenches. Archaeological work has confirmed that six others once had trenches. The rest are known from brief historical accounts.

Modern Excavations

In the 1960s, Donald Mitchell was the first professional archaeologist to excavate a defensive site, demonstrating that two defensive sites dated before the 1780s and therefore proving they were aboriginal and not built as a response to encounters with Europeans. This was confirmed in 1968 by Judy Buxton, a graduate student, who dated a trench feature near Bamfield on the west coast of Vancouver Island and discovered it was 700 years old.

In the 1960s, archaeologist Don Abbott excavated a large midden (midden is refuse such as shells and fire-broken rocks from the occupation of a village) enclosed within a trench on Ash Point in Pedder Bay, to the west of Victoria. The base of this site dated to around 1,700 years ago. Although the trench feature itself was not dated, this period represents the first major occupation of the site and is similar to dates from the bottom layers of many non-defensive sites.

Obtaining a series of dates within the trenched-off area as well as from large adjacent middens outside of the area provides crucial information in determining if a defensive site is a new village or whether it is an old village that was then fortified. Ten of the sites in the Victoria area are separate defensive villages – not found with adjacent shellmiddens. The other nine adjoin or are part of a larger midden, but do not necessarily date to the same time period as the larger midden.

Findings at Finlayson Point

In recent years, I have carbon-dated three defensive sites. One site is on Finlayson Point, part of the exposed shoreline of southern Victoria (located in Beacon Hill Park). At the south end of the Point, one can still see mounds and platforms where houses once stood along the edge of the bluff. Surface house and trench features at the north end, however, are now destroyed.

The defensive trench for the site was once 5 m (16.7 ft) wide, curving across the narrow peninsula in a 75-m (250-ft) semi-circle from cliff to cliff. Through the exposure of an end of the trench by erosion, it was shown to have been over 2 m (6.7 ft) deep.

During an excavation done prior to the construction of a new sidewalk in the park, I located the buried features of a house structure next to a concentration of shell midden at the northwest edge of the site. With help from volunteers from the Archaeological Society of BC, we uncovered multiple post-hole remains, suggesting that a house was rebuilt here several times. A date from charcoal collected from the post hole indicates the house was occupied at least around the time of 1420 A.D. to 1689 A.D.

A landslide in 1990 exposed the midden associated with this house and revealed deposits up to 1.3 m (4.3 ft) deep. Two charcoal samples were used to date the lower portions of the midden to between 974 A.D. and 1066 A.D. The depth of upper deposits would suggest that the midden dump was still being used to about the time of the housepost date.

Oral history indicates that inhabitants of this site were killed off by disease. This could have been during the smallpox epidemic of 1782 or from the spread of earlier epidemics in Siberia in 1769 or Mexico in 1519. Future work is needed to pin-point the time the site was abandoned.

The site is in a storm-exposed locality, yet the remains of food found here and the presence of human burial cairns on Beacon Hill behind the site suggest some degree of permanency in settlement.

Animal bones recovered from the site do not clearly indicate whether people came here on a seasonal basis to procure specific foods. Remains included locally available fish such as ratfish and dogfish, sculpin, greenling and salmon, with only herring being suggestive of a springtime specialization, and local birds such as the grebe and marbled murrelet. Mammal bones included deer, elk, raccoon, domestic dog, seal and porpoise. Mollusc remains were almost all from species not available in the vicinity and must have been obtained from a few miles away. The mollusc evidence could be used to argue for or against seasonal occupation.

One activity of villagers, with no archaeological evidence to support it, would likely have been the collecting of large quantities of the starchy bulbs of the camas plant. Camas once grew in abundance along the local terraces and would have been both an important food and trade item.

Correction: In shortening the text, the author inadvertently introduced an error in Part 2 (Discovery Feb. ‘97). It is recognized that Charles Newcombe took photographs of defensive sites from 1901 to his death in 1924, and William, his son, from 1923 to 1935.

Part 4: Local Sites are Dated. Final Conclusions

In recent years, I have had the opportunity to carbon-date several local defensive sites.

In 1983, I excavated the Lime Bay Defensive Site on the north side of Victoria’s Inner Harbour. Two dates place the earliest occupation between 1,200 and 600 years ago. Historic disturbance of the surface made it impossible to determine when the site was abandoned.

There is a large shell midden at Flemming Beach to the west of Macaulay Point. In 1985, when a housing development exposed an entire cross-section of the main shell midden, I extracted a charcoal sample and dated the deepest deposits of the midden to 4,151 years ago. Below this was deep beach sand in which I found a single pebble chopping tool from an earlier period.

Two defensive sites adjoin this large midden. Near the eastern end of this site, separated only by a rock outcrop and a small area of midden, there was a trench which today is mostly destroyed.

At the western end of the main shell midden is a small peninsula that once had a visible trench across it. Near this trench, I exposed a soil profile where the owner of the property was digging a new flower bed. Charcoal samples from 0.3 to 0.5 m (1 to 1.7 ft ) below the surface dated to the period 1287 to 1333 A.D. The amount of refuse deposits above and below these dates would suggest that the first occupation occurred about 750 to 950 A.D. and lasted until at least 1400. It is clear that this part of the site was used after or at a late time period in the history of the larger shell midden.

In Conclusion

Oral histories and historical documents indicate that aboriginal defensive sites were common in the late 1700s to the mid-19th century in the Gulf of Georgia. Archaeological evidence suggests there was a trend that began around 1,200 to 1,000 years ago to expand defensive sites both through the occupation of new sites and with locations adjacent to existing village sites.

Based on my familiarity with other sites in the Gulf of Georgia, this settlement pattern extends beyond my immediate study area in Victoria. This pattern may also have occurred in other time periods at different locations within the Gulf of Georgia region, as there are sites dating from an earlier period located for defense that are on bluffs several hundred meters back from the shoreline.

The change in settlement is not the result of changes in the landscape or sea level. What situations might have created conditions that lead to increased warfare and the need for defensive structures in settlements? Changes might be due to more competition from either a natural increase of population or decrease of population due to disease or warfare; to changes in the availability or choice of food sources; or to new technology and/or social organizations developing to exploit old or new food resources.

The very nature of a defensive village would demand greater social cooperation for group survival. The need to restrict one’s movements may have made necessary a more specialized focus on some food resources. Possibly reef-netting technology for large-scale salmon fishing was a result of these needs.

The dating of non-defensive sites in the greater Victoria region suggests settlement expanded significantly within existing sites and to new site localities about 1,700 years ago. And artifacts discovered after this time period show a large-scale increase in the kind related to the fishing industry. This may be the result of a population increase and a reduction in other resources that were more easily overexploited.

We need to undertake more detailed dating and analysis of animal remains, features and artifacts at these sites before any final statements can be made about the role of defensive sites in the history of First Peoples on the southern coast and beyond.

|

Between 1420 – 1689 AD |

Carbon-date for house on Finlayson Point Defensive Site. Approximate end of occupation at |

|

1400 AD |

West Flemming Beach Defensive Site. |

|

Between 800 – 1400 AD |

Lime Bay Defensive Site first occupied. |

|

Between 750 – 950 AD |

West Flemming Beach Defensive Site first occupied. |

|

950 AD |

Finlayson Point Defensive Site first occupied. |

|

Between 800 – 1000 AD |

Defensive sites in Gulf of Georgia begin expanding. |

|

300 AD |

Non-defensive sites in Victoria region begin expanding. |