Originally Published in Discovery. Magazine of the Royal BC Museum. 2007. 35:3:4-6

2007.

By Robert Moyes

Grant Keddie and the Boyhood of Adventure – How the child was father to the archaeologist.

Grant Keddie (left) at age 6 with his older brother Graham.

Grant Keddie (left) at age 6 with his older brother Graham.

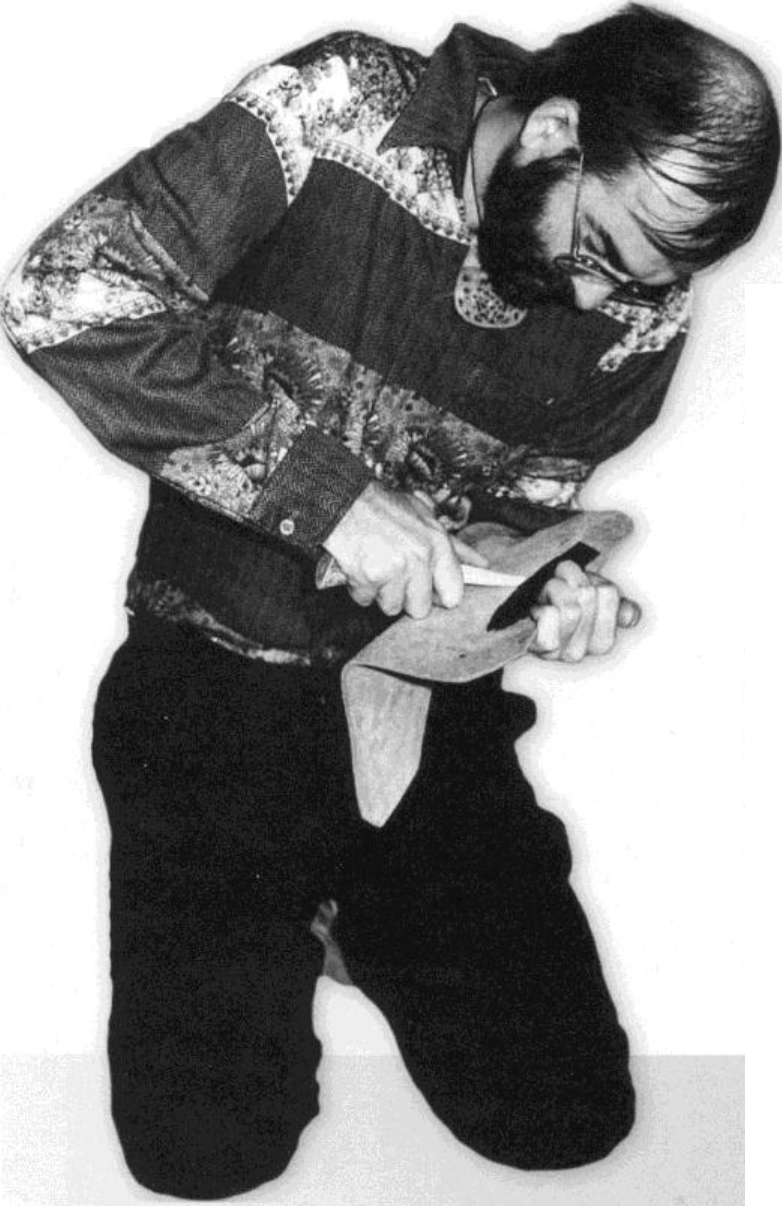

Grant Keddie is proud of being a curious fellow. And up on the 11th floor of the Royal BC Museum’s Fannin Building, this long-time curator of Archaeology uses that curiosity to help him interpret nearly 150,000 artifacts that reflect the pre-contact history, ethnography and cultural development of our many First Nations groups. “I’m one of the few archaeologists who still does experiments on tools,” says Keddie, who pursues many of his so-called “projects” in his spare time. Keddie often makes his own replica tools, speculative attempts to find out, say, what length and width of knife blade will work best to butcher a sea lion carcass (one of many such experiments he has cheerfully undertaken in the name of science).

“You find out by doing things,” explains Keddie, who also makes tools in order to use them in the manner that archaeologists think they were employed. “Afterwards, I do a comparison of microscopic edge damage between my tool and an original. If the damage is identical, then I know that the theory about how the tool was used is probably correct.”

Towering over Keddie’s worktable are dozens of sliding, nine-foot-high cabinets filled with what can often look like little more than chunks of stone and bone. But to someone with Keddie’s knowledge and power of imagination, each artifact – ranging from broken tools to tiny obsidian micro-blades and elegant spearheads painstakingly fashioned by aboriginal craftsmen 2000 years ago – tells a story. And rather than what they were used for, Keddie follows his restless curiosity until he comes up with field-tested results … and possibly some new theory that can add a further chip of knowledge to the early human history of this province.

Suddenly pulling out a ceremonial bowl shaped like a curled-up rattlesnake, Keddie asks rhetorically why this bowl would be found in an area where no such snakes existed. “One of my wilder theories is that the bowl was used to pulverize dried snake venom. It makes a bit of sense if you remember that shamans were supposed to be able to cast spells and kill people,” he adds. “There are so many mysteries about artifacts that have yet to be solved.”

It’s an ongoing challenge, one the man obviously relishes.

Wearing an extravagant paisley shirt and sporting a custom-designed amulet around his neck that comprises an 18th century Japanese ivory netsuke, antique hand-carved olive pits from China and a jade whale’s tale from BC – what Keddie laughingly calls his “corporate tie” – this is one archaeologist whose wide-ranging intellect never collects dust. And what’s striking is how little Keddie has changed since he was a six-year-old growing up in Edmonton. “We lived in a new development at what was then the outskirts of town, so I spent a lot of time out in the bush, where I collected frogs and tadpoles, watched birds and generally studied the wild world,” he says.

This young lad also made his own bows and arrows – and his experiments to find out which wood made the strongest bows were his first experience with what has become a lifelong belief in the virtues of trial and error. “I was also fascinated by astronomy, and the ideas of time and space,” he adds. “I was interested in absolutely everything – and I still am,” he smiles. “I could live several more lifetimes and still have many things I wanted to do.”

Aside from spending whole days roaming the woods and fields, Keddie passed a lot of time at the family cabin on the prophetically named Skeleton Lake (a cabin he helped build with his dad). “Mine was a childhood full of adventure and a great love for nature,” he recalls. “I found rare lizards, had encounters with Grizzly Bears, and learned how to imitate bird calls,” notes

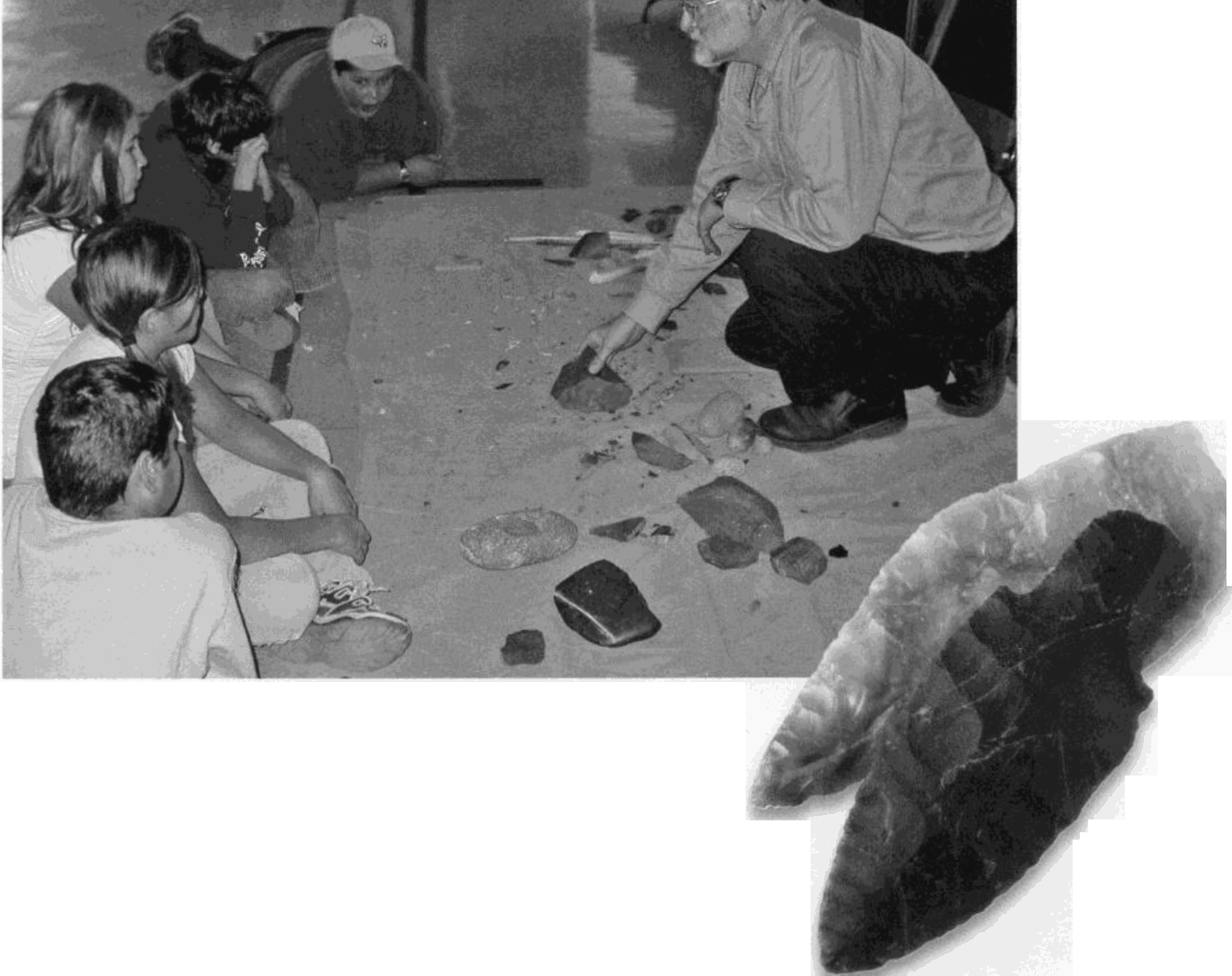

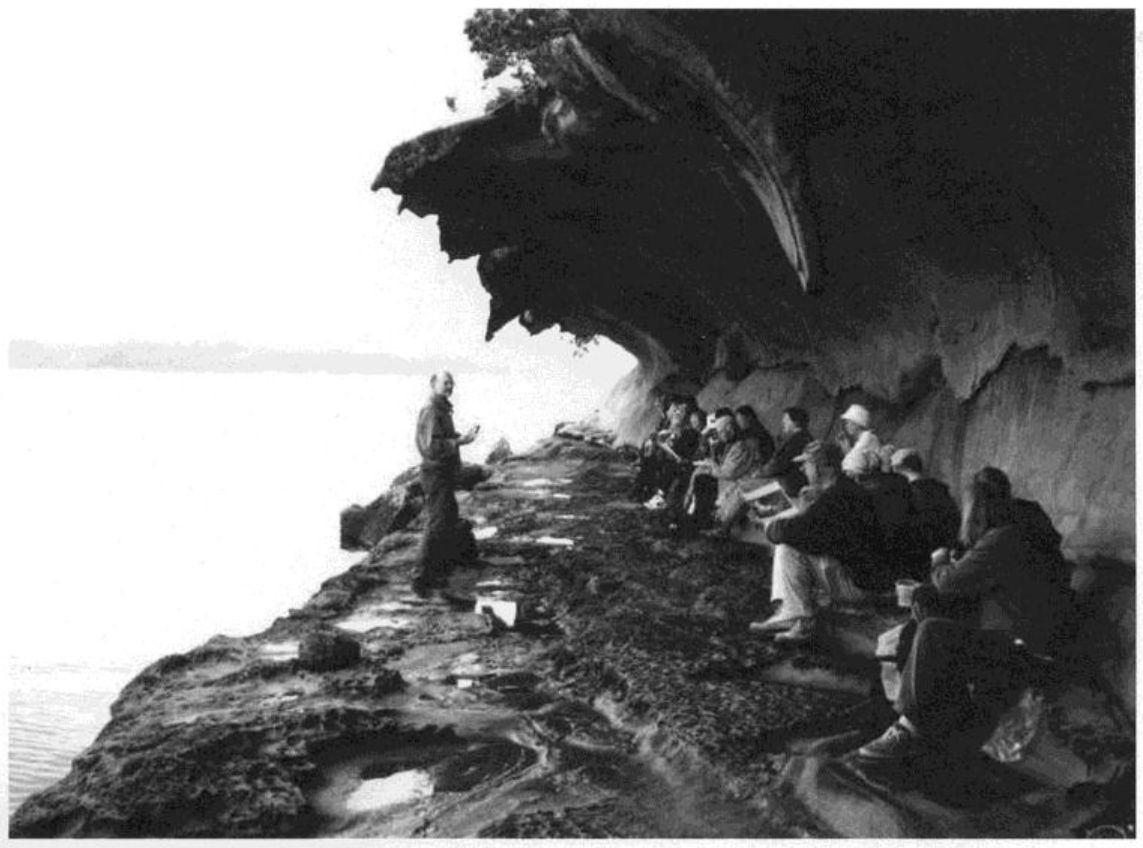

left Keddie demonstrates the making of stone tools to students from the Peace River region. Brian Apland photo. below Projective points from the RBCM archaeology collection which Keddie uses as reference when making his own.Keddie, who often snuck out of the cabin at midnight just to listen to the screech owls.

When he wasn’t observing tadpoles and dragonflies undergoing metamorphosis at a nearby swamp, the young Keddie was reading books on animals, fossils and the history of the ancient world. Once when his dad was splitting cobbles for a rock garden, one cracked open to reveal what looked like a fossilized egg inside. “My dad was always interested in having us learn things, so he went with me to show the rock to a local paleontologist,” recalls Keddie. As it turns out, the rock wasn’t a fossil: the dark, egg-like shape was caused by a differential chemical reaction within the parent rock. “That rock never made it into the garden – and I still have it in my library,” says Keddie. Two years later, when he was eight, the budding scientist went to Drumheller where he collected real fossilized dinosaur bones.

Most of the young Keddie’s interests directly or indirectly supported his passion for archaeology, and he had soon run through all the relevant books in his elementary school’s library. “That’s when I started going to museums, especially if there was some special exhibit on.” Rather than waste a popsicle’s-worth of money on bus fare Keddie would cheerfully walk almost 20 km to the University of Alberta when they hosted displays of Egyptian mummies or other archaeological exotica. After the family moved to BC the teenaged Keddie attended high school in Surrey, where he fed his appetite for information with books and specialty magazines. “I never read fiction – it was always topics like the early history of Africa and the Middle East,” he recalls. “If I had stayed in Alberta I’m sure I would have become a paleontologist,” adds Keddie. “As it was, it was a 15-minute drive to Simon Fraser University, where I majored in anthropology and archaeology.” Hired right out of university by the RBCM in 1972, Keddie has continued his lifelong pursuit of knowledge with boundless enthusiasm. Even a brief chat with the man finds you galloping off on unexpected tangents: an anecdote that starts at the famed First Nations midden on Gabriola Island can segue into a scholarly aside on the history of Chinese coins in BC, before leading to an account of how Keddie paid to have his own DNA analyzed so that he could trace his ancestors as they slowly migrated from Africa to the Middle East before ending up as Scottish Celts.

“I think it is important to have a curiosity for everything,” insists Keddie, who has a sign outside his office that reads: Reality Is For People Who Lack Imagination. (A more thoughtful sign affixed to the door adds, Each Of Us Has Something Good And Beautiful to Give To The Generations That Follow.) “Pursuing knowledge about the world around you improves our chance for survival as both individuals and as a species,” he sums up. “And that’s especially crucial on what has become an increasingly vulnerable planet.”