January 17, 2019.

By Grant Keddie

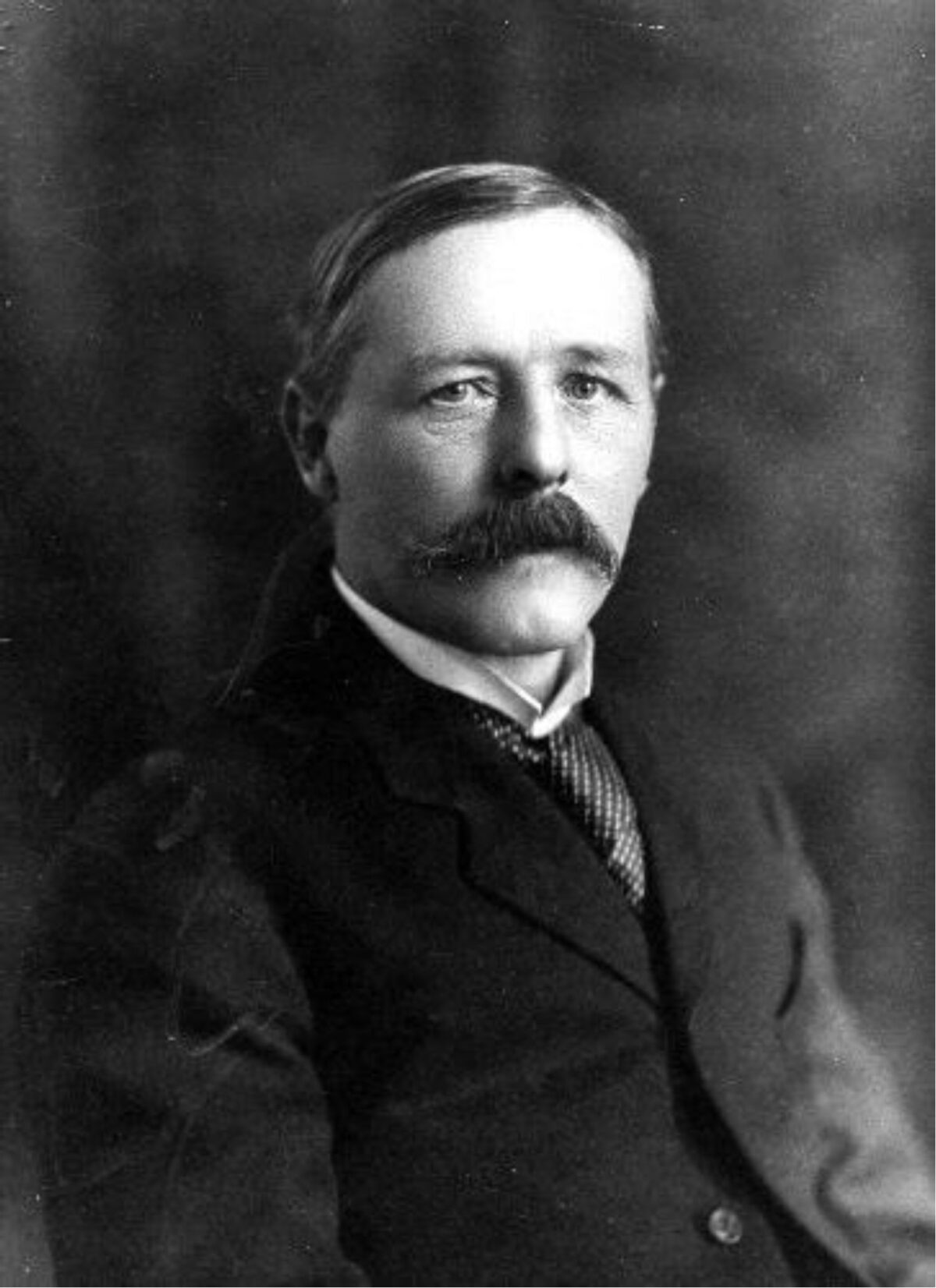

Dr. Charles Newcombe played a major role in the development of the Royal B.C. Museum ethnology and palaeontology collections (figure 1). He left behind four of his own interesting photographs that were missing the details of their context. Here, I present the story behind these images.

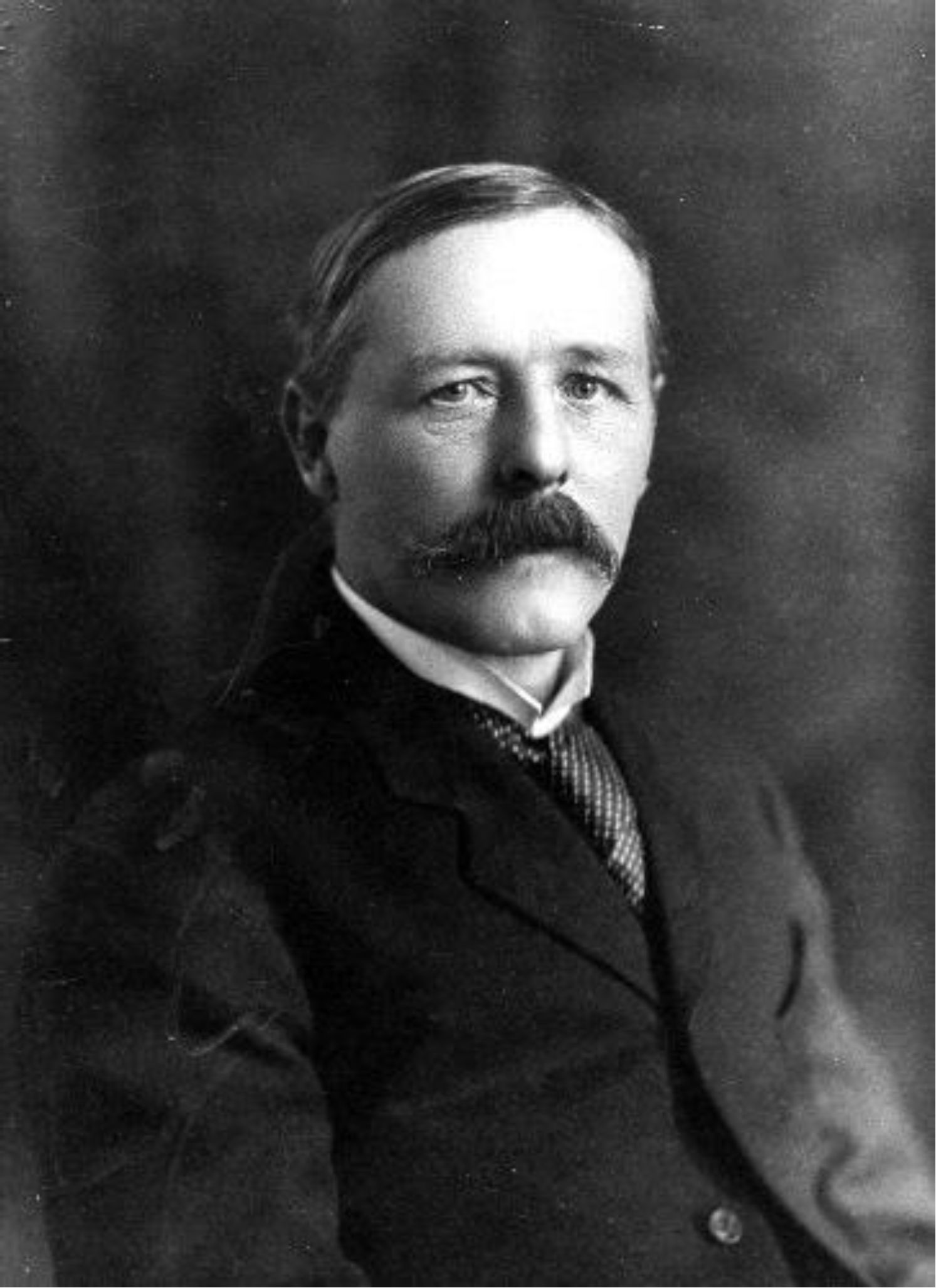

Newcombe was fascinated by the Northwest Coast paintings of the famous Canadian painter Paul Kane. In 1904, Newcombe traveled to the University of Toronto where he photographed some of the Kane paintings from the Sir Edmund Osler private collection that were on loan to the University. Newcombe was keenly interested in Kane’s composite oil painting – then labelled as No. 84 (now ROM912.1.84). This painting was made from several images that Kane sketched in 1847 (see Lister 2010: 292-293). Newcombe had a lantern slide made from some of Kane’s images that he used in public talks (figure 2).

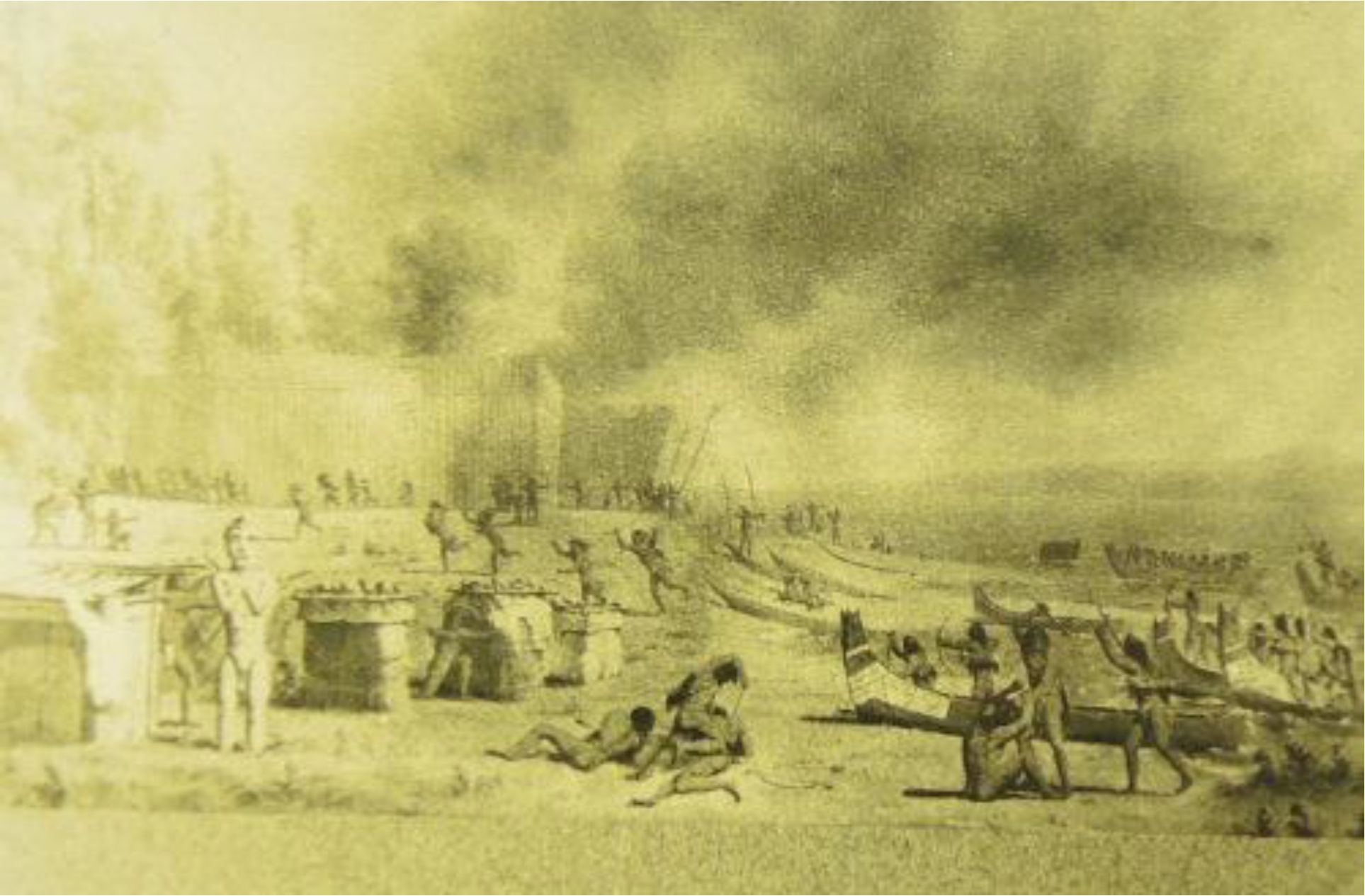

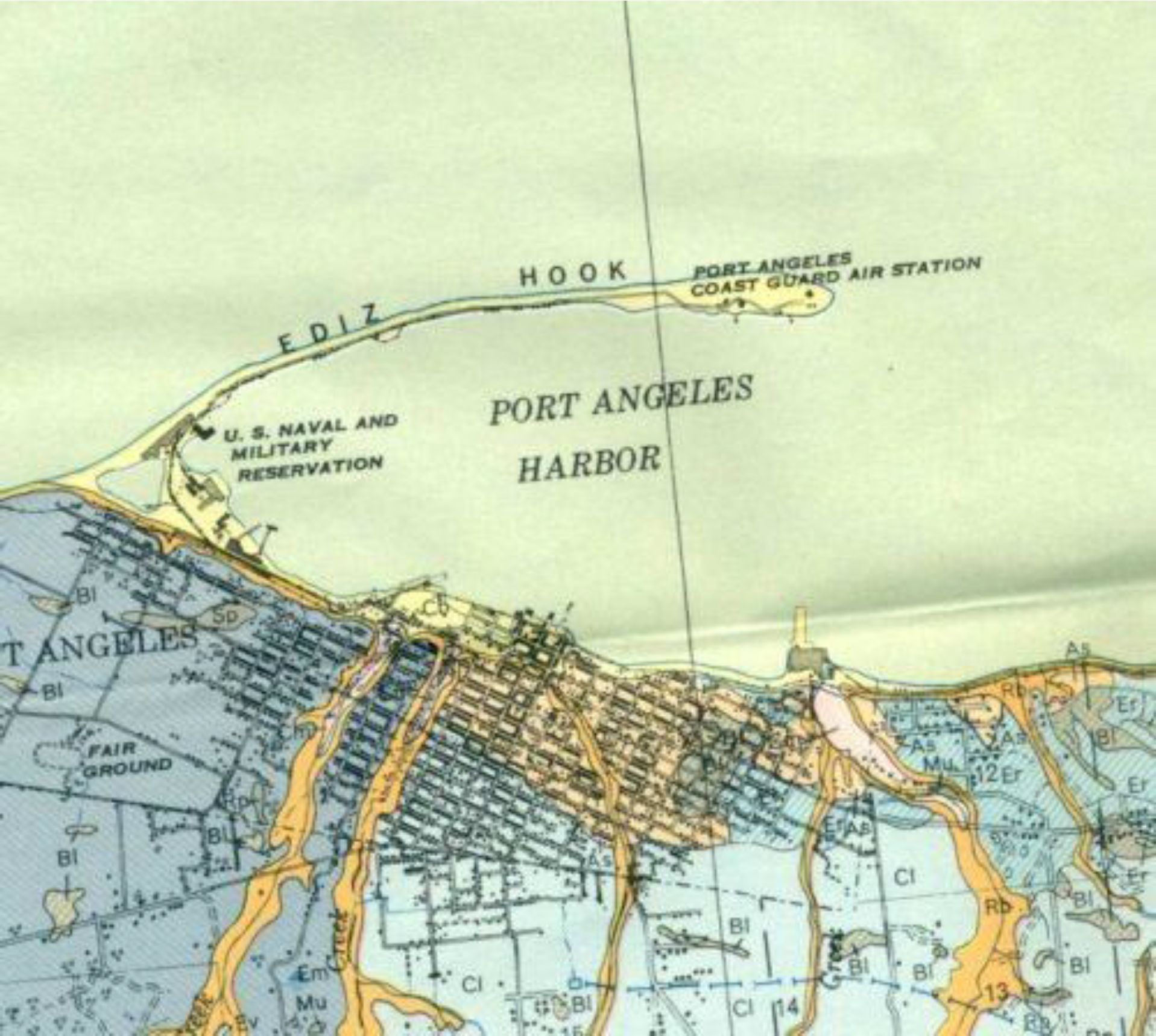

On July 4, 1907, sixty years after Paul Kane’s visit to Fort Victoria, Newcombe went in search of the location of Kane’s painting of I-eh-nus. The site was located near the mouth of Ennis Creek east of Port Angeles on the Olympic Peninsula of Washington State (figure 3).

Newcombe took four photographs (RBCM PN352; PN352B; PN353; PN353B) of the location during his visit but these have remained in the ethnology photo collection without information describing their context (figures 4-6).

Newcombe also left a typed draft manuscript of his trip to Ennis Creek which did not appear among his family papers. In the 1970s, I identified this important draft in an old box piled amongst miscellaneous natural history items in what was then the Museum’s Birds and

Mammals Division. Newcombe had a special interest in Indigenous fortified defensive sites (Keddie 2013). Images of these forts that still existed in the mid-19th century are rare. Kane’s visuals of the Ennis Creek fortified village are the best preserved of all. His interest in archaeology, ethnology, geology and natural history is expressed in his draft article, included here, where he refers to the village as “Inas”. I have corrected some of the spelling or typos from the draft, added annotations in brackets, a few notes (*) for the Appendix 1 and interspersed some images relevant to Newcombe’s commentary. Following this I have added the commentary that appeared in Paul Kane’s 1859 publication regarding his visit to the Ennis Creek village.

Newcombe’s Manuscript

Battle. Between Cllam [Clallam] & Macaw Indians, at I-eh-nus, a Clallam Fort in the Strats [Straits] of Fuca

“Directed by the nephew of the late “King George” (*1) of New Dungeness, who unlike his relative, bound to abstinence from alcohol & tobacco by his affiliation with the sect of Shaker [the Shaker Church (*2)], the writer found the site of the old village of Inas, on a point of land about a mile & a quarter to the east of the steamboat wharves at Port Angeles.

It is a wide sandy flat full of rounded pebbles of all sizes which have been washed down from the bluff of boulder clay & glacial material which forms part of the coast line along the southern shore of the Strait of Fuca.

To the west of this village site is bounded by a small pebbly creek which cuts through the bluff at this point & afforded an unfailing supply of water to the village and, no doubt both salmon& trout at certain seasons. The Bluff itself, covered with cedar, & all the common trees of this region, protected the back of the fort which fronted on the sea, & the 4th side had no natural cover.

The site is full of signs of Indian occupation, consisting of shell mound material, burnt stones, fragments of whetstones & hammers and the lines of the house places are still marked by long rounded mounds formed by the rubbish thrown out from time to time.

This is especially noticeable in the case of a carved board, the face of which is rounded & show traces of red paint on the carved surface. The west face is flat & roughly hewn. The fragment is of cedar & covered with a bright yellow lichen. [It is surprising that Newcombe does not mention the pole that he photographed (figure 6). His photo catalogue only says “Inez pole and stream”. It is likely that the large pole remnant was a major support for the corner of the old Fort].

The parallelogram occupies the portion of the sandy flat shown by Kane as fortified. Some very old Indians seen at Port Angeles will remember the incident of the burning of the fort by the Macas [Macaws] & confirm many of the details related by Kane.

Sheltered by Ediz Hook, a spit of sandy shingle which runs in a curve for nearly three miles from shore, this village occupied an ideal situation.

Useful trees, shrubs & plants noted. Cedar, Douglas fir, balsam fir, hemlock, spiraea, dogwood, willows, crab apple, thorn, goose b., current, thimble b., straw b., claytonia, onion, cherry, salal, rushes. Woods abounded in bear, elk, deer, birds of many kinds as ducks, geese (?), grouse, eagles, woodpeckers, &c.

Lighthouse at end of hook in line with cedar hill gives location of bluff above flat on west side of creek. Spanish map of Eliza, 1791, shows houses a little to east of Inas ”. (*3). [Newcombe includes on his draft a simple sketch of the top of the hill that notes on each sloping east-west sides a “bank of shell” and at the N. W. corner a “carved board with no paint”].

Paul Kane’s Visit to Ennis Creek

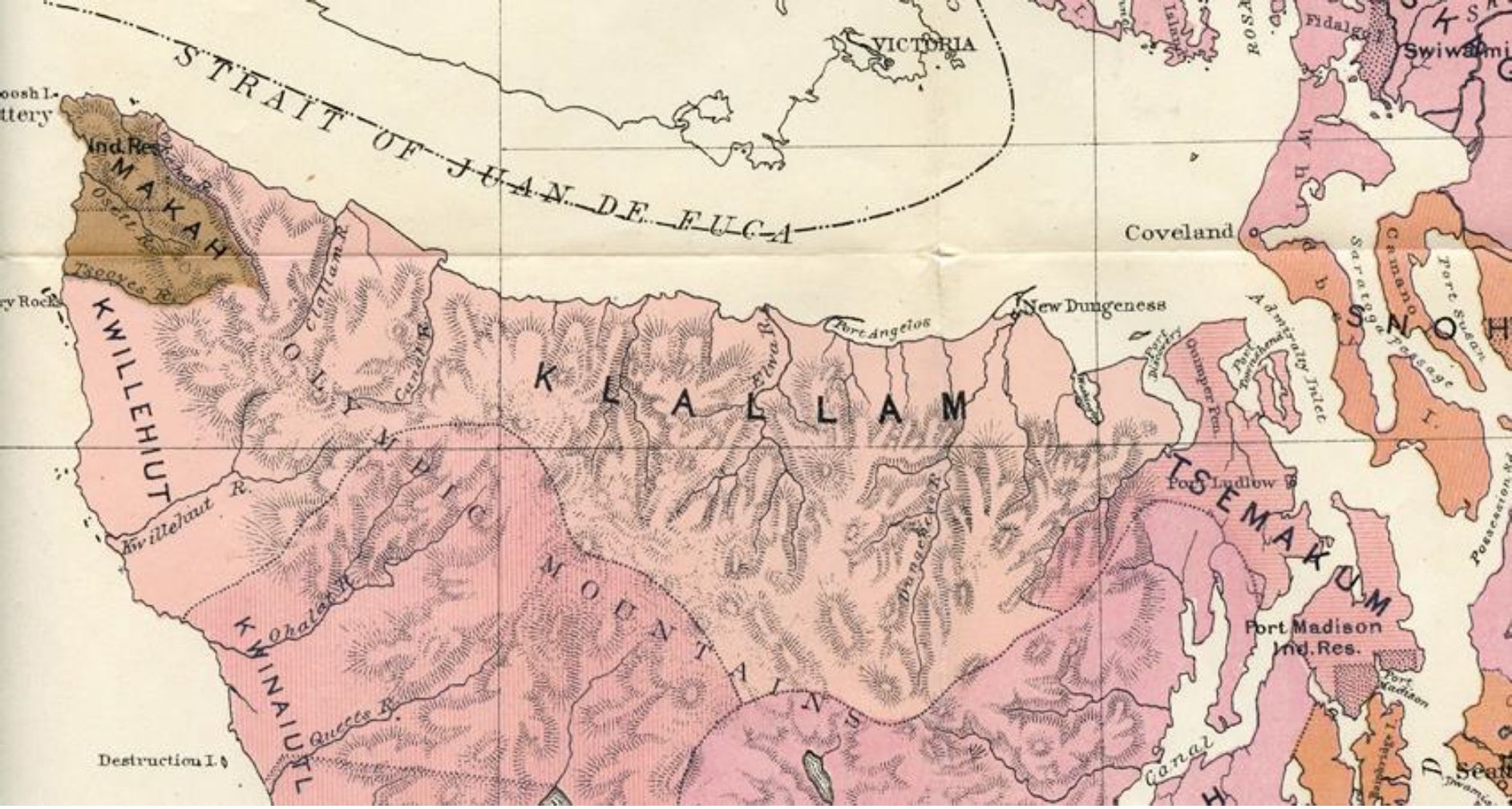

Paul Kane’s description of this Fortified site and the battle between the Makah and Klallam (see figure 8) was presented in his 1859 publication. He visited the village site of I-eh-nis from May 9 to 11, 1847. His description is as follows:

“Made a portage across the spit, and by the evening reached I-eh-nus, a Clallam village or fort. It was composed of a double row of strong pickets, the outer ones about twenty feet high, and the inner row about five feet, enclosing a space of 150 feet square. The whole of this inner space is roofed in, and divided into small compartments, or pens, for the use of each separate family. There were about 200 of the tribe in the fort at the time of my arrival. Their chief, Yates-sut-soot, received me with great cordiality. … A few months before my arrival a great battle had been fought with the Macaws, in which the Clallums had suffered very severely. It originated in the Clallums having taken possession of the body of a whale which had been killed by the Macaws, but had got away, and was drifted by the current to the village. The Macaws demanded a share of the spoils, and also the return of their spears, some fifteen or twenty in number; which were sticking in the carcase; both demands were refused, and a feeling of animosity sprang up between the tribes.”… A few months after the quarrel about the whale, the brother of Yellow-cum, the head chief of the Macaws, went to Fort Victoria to trade for ammunition and other necessities, and on his return was attached by the Clallums. He and one of his men were killed, but three others escaped, and succeeded in getting to Cape Flattery, where Yellow-cum resided. Immediately upon hearing of the death of his brother, Yellow-cum fitted out twelve of his largest canoes, with twenty warriors in each, and made a sudden descent upon I-eh-nus; – after fire was set to the grass and wood – the Clallam were forced to run out and fight – Yellow-cum took prisoners, mostly females, who were made slaves, and he had eight heads stuck on poles in the bows of the canoes on his return. These heads were carried to the village, and placed in front of the lodge of the warriors who had killed them as trophies” (Lister 2016).

During the same year as Paul Kane’s visit, the region around the Ennis Creek village was surveyed between July 22-28, by Captain Henry Kellet (Kellet 1847). He showed three

“Indian village” places west of Ediz Hook. The furthest village east below the tip of Ediz Hook is the Ennis Creek village. This survey information formed a portion of the George Richards map of 1859 (Figure 9).

Charles Newcombe’s notes and his photographs in the Royal B.C. Museum collection, taken on his 1907 journey, have contributed to providing a better understanding of the physical landscape and context of Paul Kane’s unique imagery.

Appendix 1. Notes on Charles Newcombe’s Draft article

(1) It is likely that the person who guided Newcombe was Lah-ka-nim called “Prince of Wales”, who was still living in the 1930s. It was common for high ranking Klallam peoples to take on names of high-ranking Europeans. The “King George” mentioned was S’Hai-ak, the brother of Chits-a-mah-han or Chetzemoka [c.1808 -1888], who was also called the “Duke of York” and recognized by Europeans as a “chief”. Chetzemoka was the leader of a mixed group of about 200 Chemakum and Clallam peoples living at Port Townsend, Washington. He had two wives Chil-lil or Jenny Lind and See-hem-itza or “Queen Victoria”. The latter was the mother of Newcombe’s guide Lah-ka-nim. His uncle S’Hai-ak or King George was the older brother of Chetzemoka and was recognized as the “chief” of the Port Townsend peoples before him. Lahka-nim or the Prince of Wales, was named after his grandfather who was present at the time of Captain Vancouver’s visit in 1792 (McDonald 1972; Castile 1985). S’Hai -ak is seen in a drawing done during his 1848 visit to Victoria one year after Kane’s visit (see Keddie 2003).

(2) The Indian Shaker Church is a blend of Christian and indigenous religion that originated in lower Puget Sound in the 1820s. It was founded by John Slocum, a Puget Sound Squaxin man in his 40s who, it is claimed, died and came back to life.

(3) I agree with Newcombe here that the Elisa 1791 map, Carta que comprehende, that shows two houses to the east of Port Angeles are likely too far east to be at the location of Ennis. Erna Gunther (1927:174), mistakenly shows I’e’ nis west of Tciwi’tsen near the base of Ediz Hook. This location is too far west. Gibbs (1855:22) description is not specific and is only given as “Yennis, at Port Angeles or False Dungeness”. A map that clearly shows a village at Ennis Creek is the 1853 map of Lieutenant James Alden (Alan 1853). Henry Kellet’s information shown in figure 9 is also shown on a second 1859 map (America N.W. Coast. Strait of JUAN De FUCA. Surveyed by Captain Kellett, R.N. 1847. Haro & Rosario Straits. By Captain G.H. Richards, R.N. 1858. Admiralty Inlet and Puget Sound. By the United States Exploring Expedition, 1841. Coast South of C. Flattery by the same in 1853).

References

Alden, James. 1853. (KNo.5) U.S. Coast Survey. Reconnaissance of False Dungeness Harbour, Washington. Lieutenant James Alden. U.S.N. Assistant.

Castile, George (editor). 1985. The Indians of Puget Sound. The Notebooks of Myron Eells. University of Washington Press.

Eells, Myron. 1886. Indian Shakers. Ten Years of Missionary Work among the Indians at Skokomish, Washington Territory 1874-1884. The Post Treaty Years.

Gibbs, George. 1855. Pacific Railway Reports. Vol. 434. Report of Mr. George Gibbs to Captain Mc’Clellan, on the Indian Tribes of the Territory of Washington. Olympia, Washington Territory, March 4, 1854. Washington.

Gibbs, George. 1877. Tribes of Western Washington and Northwestern Oregon. Part II. In: Department of the Interior. U.S. Geographical and Geological Survey of the Rocky Mountain Region. J.W. Powell. Contributions to North American Ethnology, Vol. I. Washington: Government Printing Office.

Gunther, Erna. 1927. Kallam Ethnography. University Publications in Anthropology, 1(5)171-314. University of Washington Press. Seattle, Washington.

Keddie , Grant. 2013. Aboriginal Defensive Sites. Four part series was published in Royal British Columbia Discovery. News and Events: Part 1: Dec. 1996/Jan.

1997 Vol. 24 (8):7-8; Feb. Part 2: 1997, Vol. 24(9):5; Part 3: Apr. 1997, Vol. 25(1):4-5; Part 4: June 1997, Vol. 25(2):5.

Keddie, Grant. 2003. Songhees Pictorial. A History of the Songhees People as seen by Outsiders, 1790-1912. Royal B.C. Museum, Victoria, Canada.

Kellett, Captain Henry. 1847. Victoria Harbour. Hydrographic Office. America N. W. Coast. Vancouver Island. RBCM Archives CM A215/149.

Lister, Kenneth R. 2016. (Editor) Wonderings of an Artist Among the Indians of North America by Paul Kane. Royal Ontario Museum.

Lister, Kenneth R. 2010. Paul Kane. The Artist. Wilderness to Studio. Royal Ontario Museum Press, Toronto. Pages 292-293.

McDonald, Lucile. 1972. Swan among the Indians. Life of James G. Swan, 18181900. Binfords & Mort, Portland, Oregon.

Richards, George. 1859. Haro & Rosario Straits. Surveyed by Captain G.H. Richards and Officers of the H.M.S. Plumper. 1858-9. (see Kellet 1847 for relevant portions of this map).