May 10, 2019.

By Grant Keddie

Introduction

In 2006, the “Spirit bear” was adopted as the provincial mammal of British Columbia. The term “Spirit Bear” has to a large extent been overused as a media hype word. It has often been misinterpreted as a direct aboriginal name of a unique type or species of bear. The circular movement of information between indigenous peoples and popular writers, have created some modern myths such as comments that white bears, also referred to as “ghost bears”, were not traditionally hunted. Today they are referred to as a subspecies of black bear called Ursus americanus kermodei.

The environmental movement of the western world has over-simplified the portrayal of all white coloured black bears by using them as a symbol of political opposition to the destruction of our valuable ecosystems. In a positive way this has produced an expanded awareness of the role of bears in the forest ecosystems of British Columbia and resulted in the protection of some of our valuable habitats. However, we must see the protection of habitats and the genetic diversity of all plants and animals as important. Discussions need to expand beyond what we call “endangered species” to what we think of as “common animals” that have, and continue to be, extirpated from many parts of our Province. Caribou (which are reindeer) once expanded over large areas of the Interior of the Province. It should not be necessary to find ones with red noses to justify saving their habitat.

The Strategic Plan for our planets biodiversity developed by participants to the 2010 Convention on Biological diversity adopted 20 targets. Target 11 involves making 17% of land and inland waters and 10% of coastal and marine areas into conservation areas (Piero et al 2019). By world standards British Columbia is a leader in developing conservation areas like the Great Bear Rain Forest. However, as Piero and colleges emphasize, we cannot use square kilometers as a measure of success but need to document the biodiversity impacts of conservation areas. By placing a focus on protecting white coloured black bears we need to understand what effect are we having on the bigger long-term picture of the genetic diversity of black bears.

What makes a White Coloured Bear

The white fur coloration in bears is caused by a single recessive gene called Mc1r, a melanocortin 1 receptor which is involved in melanin production. Melanin is primarily responsible for the pigmentation of the skin, hair and eyes of humans and other animals. The chemistry involved here is called melanogenesis. The

Mc1r gene produces enzymes such as tyrosinase which play an important role in melanin synthesis. The same chemical process is used today in making tooth whiteners, where chemicals are used to suppress the tyrosinase enzyme and stop the production of colouration (see Reimchen and Klinka 2017; Hedrick and Ritland 2011; Klinka and Reimchen 2009; Marshall and Ritland 2002; Ritland et. al. 2001).

The chemistry produced by this gene causes some bears fur to be white or black. If both a female and male have the recessive Mc1r gene, one of their four offspring will have white hair and two of them will have recessive genes for white hair. A white furred bear mating with a bear with the recessive gene will have two white bears and two with the recessive gene. There are other genes related to thyroid hormone production that create combinations of white and black fur colours in bears (see Crockford 2006; 2003).

There is currently discussion as to how one uses genetics (with or without obviously physical morphology) to define an animal subspecies. It is likely there are genes with currently unrecognized functions that are far more important for the survival of black bears than genes that affect hair colour. Today we could target and edit out the single gene that produces the tyrosinase enzyme thataffects pigmentation, and make all black bears white albinos if we choose to. Responsible people, of course, would not do this, but it emphasizes how such minute genetic differences can affect cultural attitudes and land use policies that affect species diversity and the future of animal and human survival.

The flogging of the name “spirit bear” stems out of activities of the early 1900s when there was an over-abundance of new species and sub-species of bears named on the bases of sometimes flimsy physical evidence (see Merriman 1918; Holzworth 1930). In 1905, we saw the naming and promotion of black bears with the recessive genes for white fur being mistakenly given status as a separate species, Ursus kermodei – after the Provincial Museum director Francis (Frank) Kermode.

White Coloured Bears and the Collection of Specimens

White coloured bears were documented in Northwestern North America as early as 1805, during the Louis and Clark expedition. In the 19th century British Columbia Indigenous people were known to bring in white bear skins to fur traders. Mayor Findlay of Vancouver wrote about his observations of white bear skins: “I have in my possession a skin which I secured in 1896. In Bella Bella in the store of John Clay, five skins at one time, brought there by the Bella Bella Indians of Princes Royal Island. I have at other times seen skins of this bear in Robert Cunningham’s store at Port Essington, as well as one or two in cannery stores in Rivers Inlet” (Daily Colonist Nov. 23, 1912, p. 6).

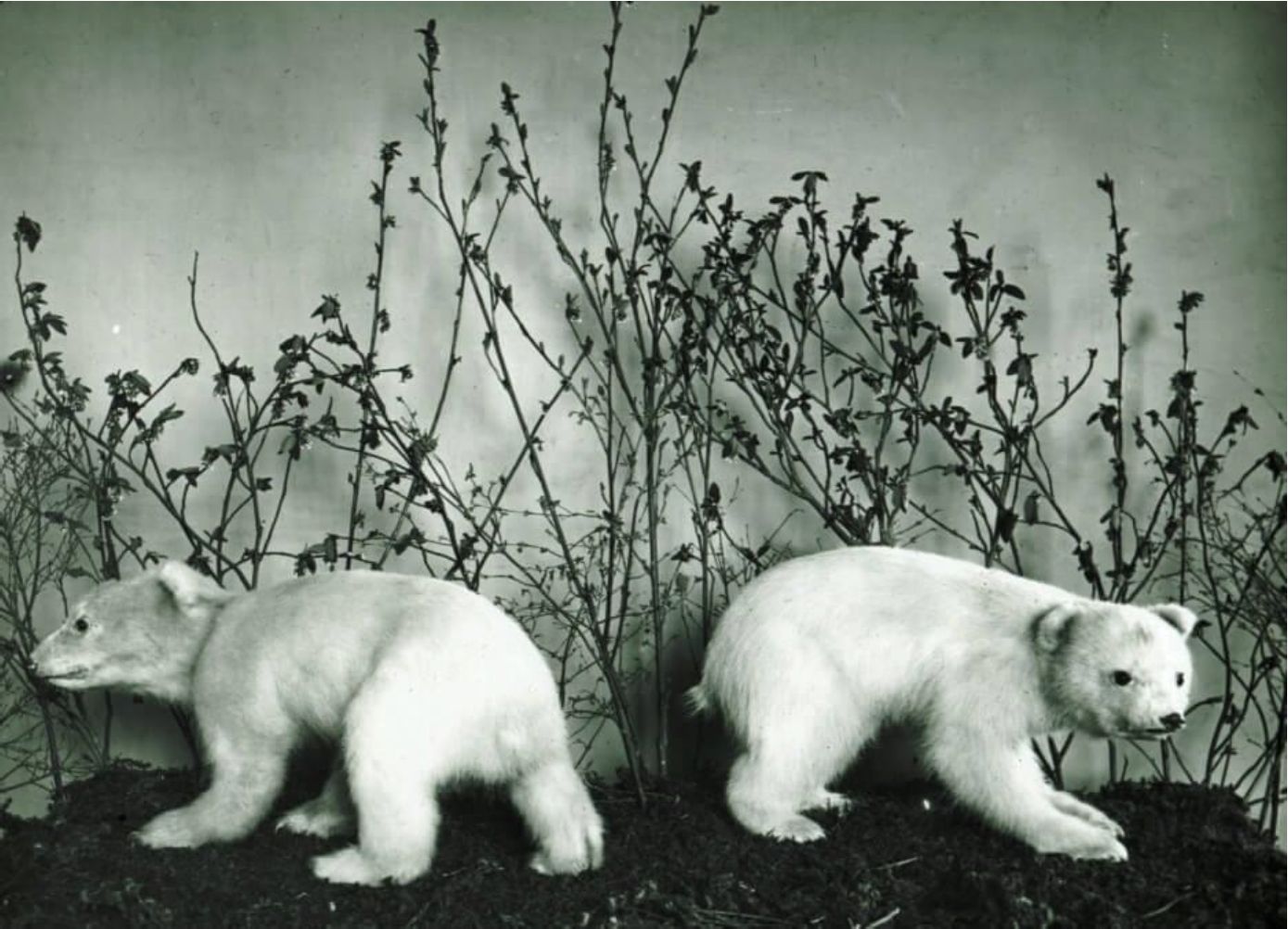

It was Robert Cunningham, of Port Essington, who previous to 1904, provided Francis Kermode of the Provincial Museum with the first white furred bear specimens which included a mother and two cubs. These were mounted at different times in two museum display cases seen in figure 2a&b. It was reported that Kermode was “at a loss to classify it” and sent the skin of a female bear to Dr. W.T. Hornady, the director of the New York Zoo. Hornaday was in Victoria in 1900, where he “was led to believe that such a white bear existed by the discovery of a skin at the premises of J. Boscowitz” (Daily Colonist 1905; 1925). The mother bear and cubs were mounted specimens that were not catalogued into the Museum collection at the time they were received. The Provincial Museum’s 1909 Natural History & Ethnology Catalogue, in referring to the Ursus Kermodei (Hornaday) notes that: “now the species is represented by a group of five specimens” (1909:18). This reference seems to refer only to those five mounted bears shown in the display case in the same publication. At this time only four specimens had received catalogue numbers, which did not seem to include one or two of these mounted bears. The two cubs shown in the exhibit case were later given catalogue numbers RBCM 020317 and RBCM 020318.

The Museum received a male partial skull and white skin of a bear from Gribbell Island in May of 1904 (RBCM 001369). This became the type specimen for what was later seen as a species and then a sub-species. Other specimens of white coloured black bears in the Royal B.C. Museum collection include another two from Gribbell Island. One was the skull of an immature bear (RBCM 001371) collected May 22, 1906 and the other a mandible of a young bear (001638) collected May 28, 1907. Two specimens were later collected from Princess Royal Island, an adult skull (001367) collected on June 1, 1908 and an adult male skull and skin (001370) collected May 22, 1910. Future DNA analysis will be needed to match a few of the skins with the other catalogued remains.

In 1911, “One whole specimen Kermode’s white bear” was shipped to Vienna Austria for an exhibit at the international Sportman’s Show which was reported on by B.C. hunter Warburton Pike (Daily Colonist 1911). This resulted in an international interest in acquiring specimens of the white bear. In 1912, the Victoria Daily Colonist reported that Dr. French of Washington was willing to pay $250 for a live white bear (Daily Colonist 1912b).

The First Live white coloured black Bear Captured

A live six-month old white colored black bear was captured on Prince Royal Island in 1924, by Indigenous people and brought to Ocean Falls where it was sold to a Virginian, O.W. Flowers for $60. Flowers brought the bear to Powel River and then to Vancouver. It was seized by the Game Commission in Vancouver and sent to Kermode in Victoria. It was put into a cage in Beacon Hill Park on July 31, 1924 (figure 3). It remained in the Park until it died in December 1948. The skull and skin where put in the Provincial Museum collection on December 5, 1924 (RBCM 005526).

Much later two specimens came to the RBCM from the Terrace area, an immature male skin and skeleton collected in September 1, 1974 (RBCM 009047) and a skin, skull and hyoid bones collected in May 1985 (RBCM 016007). A specimen from the Penticton Game Farm that died at the age of 19 years was acquired on January 26 1990 (018558).

Current Subspecies Designations

More recent summaries based on morphological studies have defined five subspecies of black bears in British Columbia: ursus americanus altifrontalis, ursus americanus carlottae, ursus americanus cinnamonum, ursus americanus kermodei and ursus americanus vancourveri (Hatler et. al. 2008). Ongoing DNA studies have, so far, identified three subcontinental clusters (lineages or haplogroups), which are further divided into nine geographic regions. The Western genetic population cluster included the region from western Alaska along the Pacific Coast to the American Southwest (Puckett et. al. 2015). More extensive whole genome research will be needed to gain a better understanding of the range of genetic diversity and the extent of the various recessive genes found in black bears in British Columbia.

Traditional Indigenous Beliefs

In traditional societies, indigenous people were very aware of the complex physical and behavioral diversity of animals. The term “Spirit bear” is a little more complex in its meaning than what is generally presented in the media. Indigenous peoples knew that this was a variation of the black bear. If we were to go back in time and observe Indigenous bear hunters we would probably label them all – to use the modern jargon – as “bear whisperers”. Before the introduction of the rifle, bears were hunted in their winter dens and caught in dead fall traps (see appendix 2. Bear Traps and Indigenous Laws Pertaining to

Bear Hunting). Detailed knowledge of bear behavior was crucial for survival. First or second-hand observations about bears by Indigenous peoples are scattered through the ethnographic and historic literature. A selection will be presented here that make reference to the complexity of bear fur colours and the indepth relationship of Indigenous peoples with all bears.

The term Moksgm’ol (different ways of writing it) which can be interpreted as “spirit bear” is used in a Tsimshian Raven creation story. Various Tsimshian and Niska families have held family crests with names translated as “white bear”; “white grizzly”; “robe of white bear”; “hat of white bear”; “grizzly of winter”; “robe of white breast [of bear]”. There are both grizzly and black bears with various degrees of white as well as albino bears (Sapir 1915). Figure 4, shows a person dressed in a bear costume in a theatrical ceremony that demonstrates the alliance of the Fort Wrangell Tlingit chief Shakes with the bear family from whom he traces his descent (Niblack 1888).

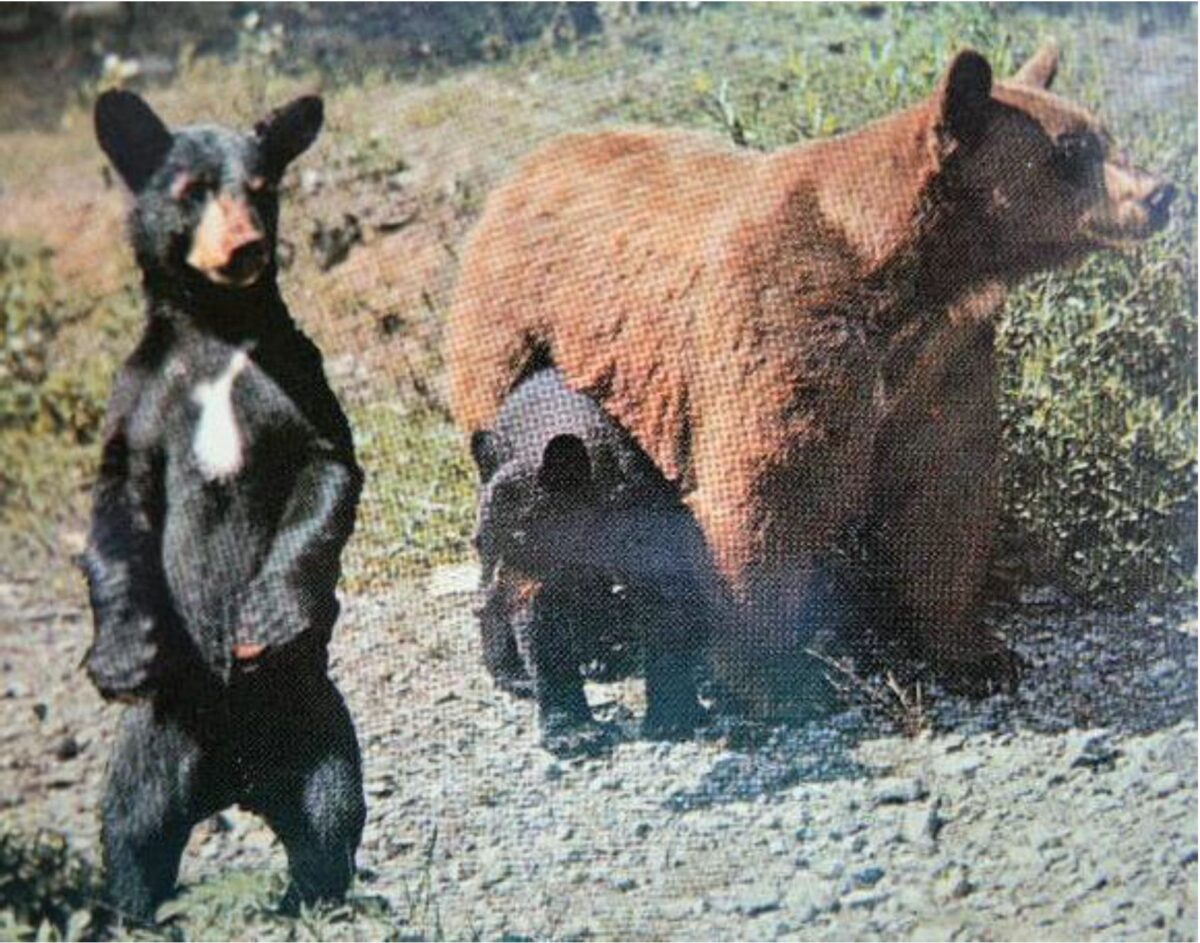

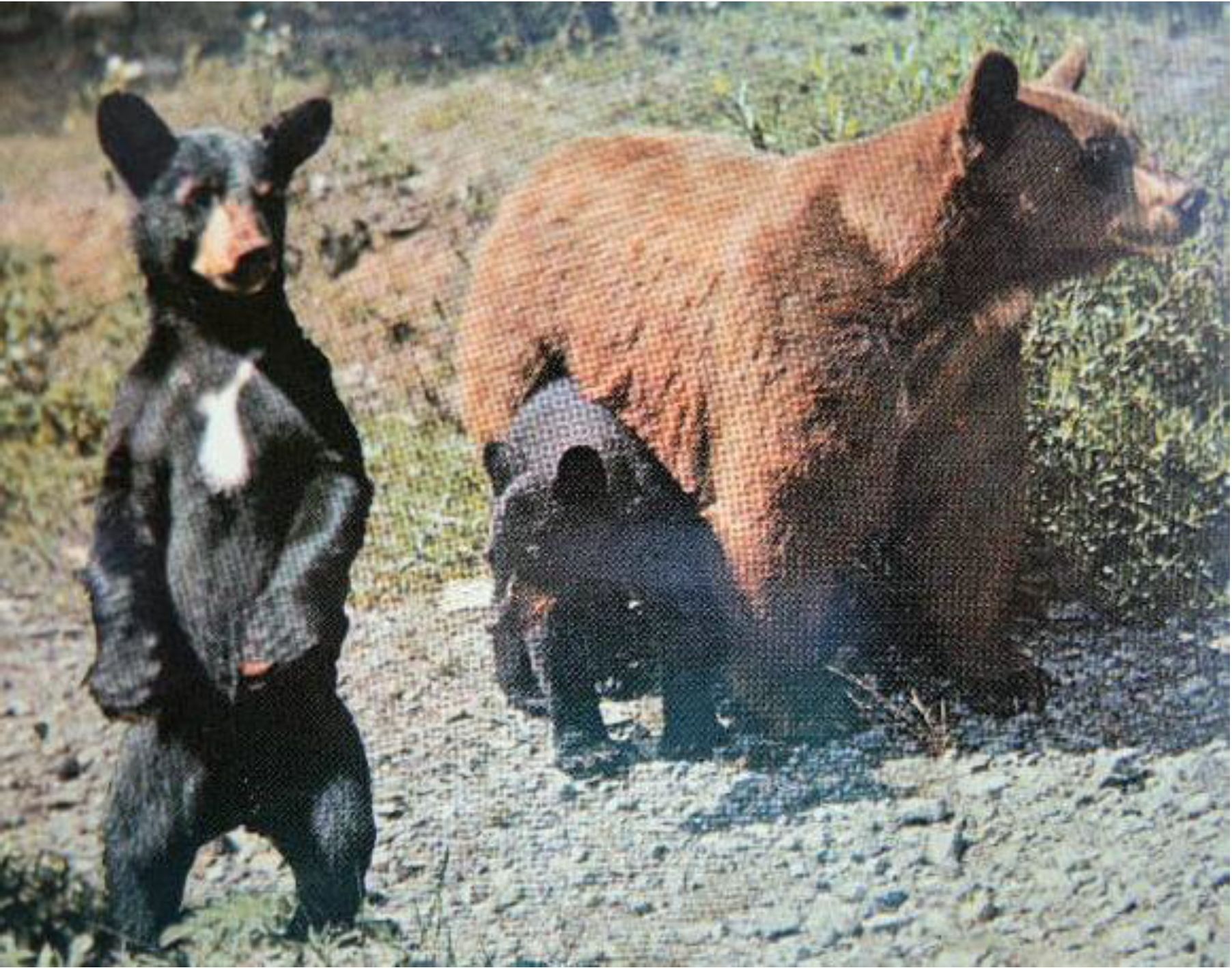

In 1972, I had discussions with the late Leo Taku Jack (1909-1979) of Atlin, who told me about the variations in white markings on the belly, sides and necks of black bears that he hunted along the Nakina and Taku rivers in the 1930s to 1950s period (see figure 5).

Indigenous bear hunters were good observers and aware that black bears came in variations of browns and various degrees of creamy white, as well as the white of albinos. When I talked to the Bella Coola bear hunter, Clayton Mack in 1969, he would specify white markings on grizzly bears when telling stories of hunting episodes. This seemed to be a way of remembering events surrounding individual bears.

Individual bears might be noted in stories because of their distinct colour patterns – but they were all recognized as being black bears (Ursus americanus) or grizzly bears (Ursus horribilis) and noted as such in the various indigenous languages. Because of genetic variation there is a greater propensity for certain colour variations to be located in specific regions. Pale blue-grey, coloured individuals of a black bear litter were more common near glaciers in the area from Mount Saint Elias to the Skeena River. Hunters often called these “glacial bears”. George Emmons recorded observations of Tlingit hunters in the 1890s. The Tlingit called all black bears “tseek” but recognized colour phases. They called glacier bears “klate-utardy-seek or klate-ukth-tseek” meaning “snow like black bear” or “tseek noon” meaning “grey black bear” (Emmons 1991:133).

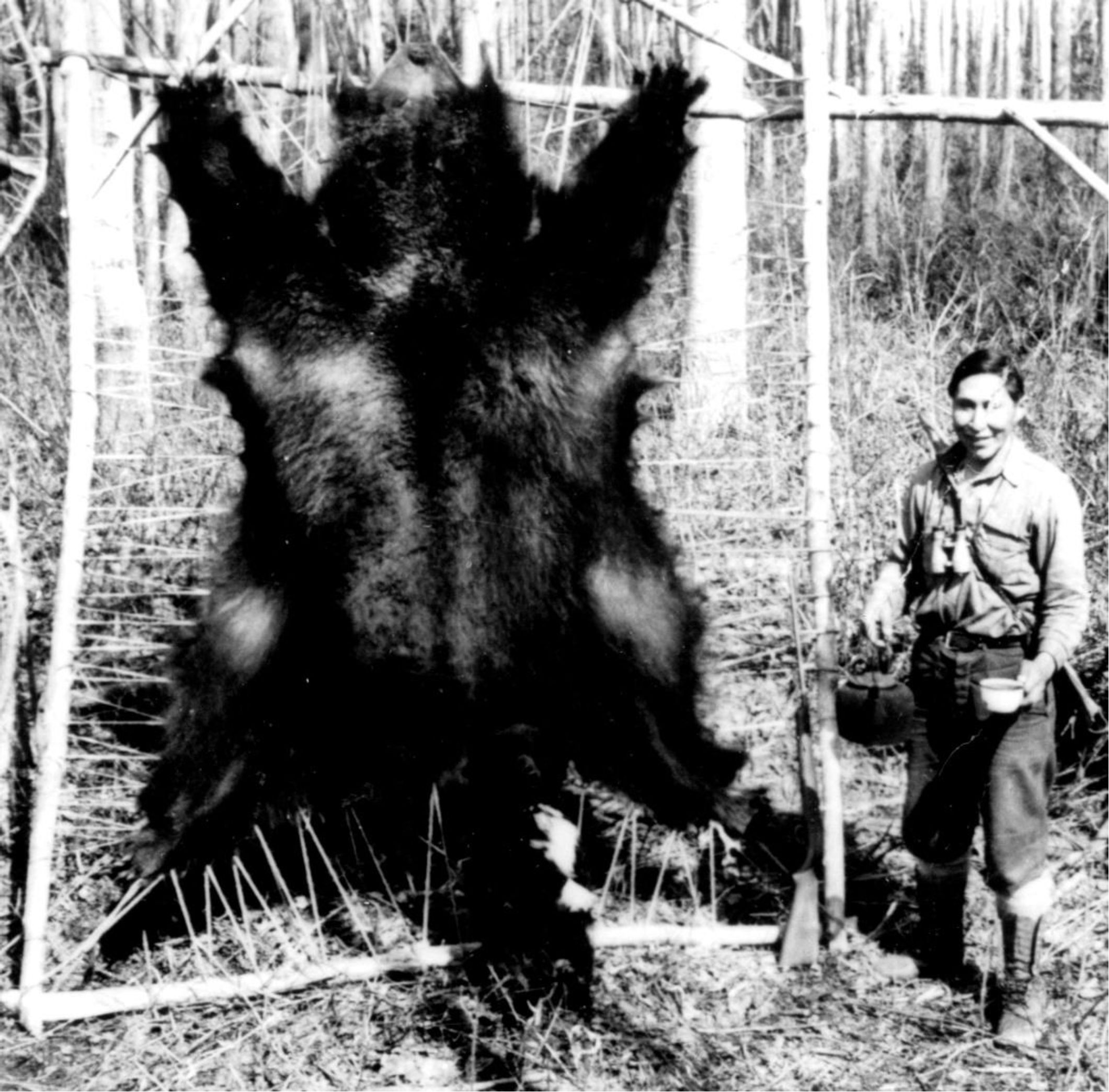

Based on hunter’s accounts and fur trade records, the all white black bears were once more widely distributed along the mountains of the mainland coast from the Skeena River to the Bella Coola regions but have since been extirpated from much of the area. White bear skins were rarer and therefore more highly valued. Cultural selection in the past may have played a role in reducing the gene pool that allowed for the recessive genes to take affect and produce more white furred bears in some areas.

It appears from early written accounts that there were a greater occurrence of regional colour and or size variants of both black and grizzly bears (see appendix I). Over hunting in the last one hundred and fifty years may have exterminated some of these regional genetic variants. In 1909, Richard Pocock presents the state of knowledge of non-indigenous peoples about bears of the northern coast forests: “The White bear (Ursus Kermodei), a few specimens of which have been shot at points along the extreme northern coast, are confined to a very limited area; but a similar variety, ranging in colour from almost pure white to a dirty grey, are seem or shot occasionally in the Western Cascades from Bella Coola north to Taku River, including the lower reaches of the Skeena, Nass and Stikine rivers. These bears are small in size, and called by the various names of white bear, rock bear, white rock bear, blue bear, glacier bear and ice bear” (Pocock 1909).

Pike notes in referring to “Ursus Kermoda” in 1910, that: “this little white bear has so far been found only in that part of the coast range of mountains which lies immediately South of the Skeena River and on the adjacent islands known as Gribbell and Princess Royal Islands, and perhaps a dozen specimens in all are to be seen in the museums of North America. It has lately been classified by American naturalists as an entirely distinct species of bear; but there is still no record of any white man having seen this animal in the flesh, although now and then an Indian brings in a skin to one of the small trading posts of the mouth of the Skeena.” (Pike 1910).. ‘ ‘ ‘

Holzworth, while on Admiralty Island in 1928, noted that an elderly Indigenous person told him of “a very peculiar type of bear, a dark brown with a yellow stripe which runs all the way down its sides from the shoulders to the rump, about four inches either side of the back bone. He saw two or three hides himself, all from the same locality on Admiralty Island. They were killed by Anderson a white man about fifteen years ago, who found them in the interior of the northern section of the island. An Indian had killed two or three similar ones on Chichagof Isle” (Holzworth 1930:73-74). ‘

It was generally believed by indigenous peoples that the spirit of a bear (as with other animals) could be acquired as a guardian spirit. Bear spirits were considered one of the more powerful spirits. Clan crests, with social and economic rights, are linked to these early encounters between humans and bears.

The bear hunter had to purify himself by bathing and fasting. It was important for the hunter to refrain from announcing that he was going bear hunting for it was believed that a bear could hear and understand everything that humans said and be forewarned of its approaching death. When a man killed a bear he and those with him painted their faces and sang a bear song or prayed to the bear as a way of appeasing or thanking it for allowing itself to be killed. When being butchered it was believed that the bear could sing through the body of the hunter.

Sometimes certain parts of the black bear would be ritually burned during a prayer ceremony (see Swanton 1908:228-229; Swanton 1905:94-95).

In 1970, I was told by the late Jack Koster of Canoe Creek a story of an experience of his father in the 1920s when he went hunting with an Indigenous uncle who was an old bear hunter from the Canoe Creek Reserve. After the bear was killed, the old hunter chanted a prayer and “cut off the tip of th e nose and tongue and took out the bear’s eyes and eardrums to bury together. They believed that a bear’s spirit would return in the form of a bad man to seek revenge. This was necessary to eliminate the senses so the bear – as the Indians said – ‘ will not find me again’.”

Summary

The importance of bears in the cultures of Siberia and their similarity to those of cultures of the New World was brought to the forefront of academic discourse by the publication of A.I. Hallowell on Bear Ceremonialism in the Northern Hemisphere (Hallowell 1926).

On the Eastern Pacific Coast bear imagery can be seen on everything from monumental poles and house screens, to boxes, rattles and combs. These physical objects are a manifestation of a complex way of life that involves Indigenous beliefs and practices. Bears have played a role in the ceremonialism and magico- religous practices of human cultures across the northern forests of the world for thousands of years.

Indigenous traditions suggest that bears are the shamans of the animal world. Skinned bears resemble humans. On the northern coast bears are considered ancestors due to the earlier encounters, and sometimes resulting marriages, between transforming bears and humans. Clan crests, with social and economic rights, are linked to these early encounters between humans and bears (for example see: Swanton 1908:228-229; Swanton 1905:94-95) .

On the west coast of Vancouver Island, the butchered remains of bears are commonly found in cave and rock shelter sites. One recorded site, that was briefly visited, is reported to have contained 22 bear skulls in four piles. Bears appear to have been, at least, partially butchered in these more remote locations away from village sites (Keddie 1994). There are still stories to be told about human-bear relationships waiting to be revealed by archaeology.

Black bears with the genetic variants that produce white or partly white furred bears are believed by indigenous peoples to have special spirit powers – but so do all bears. Bears that have unusual markings and more extensive white in their fur may be seen as being of special significance because they occur more rarely. Indigenous peoples, however, did not see all white bears as a separate and distinct species and give them distinct names meaning “spirit bear”. Older traditions show that white markings allowed individual bears to be identified, and that indigenous understanding was much more complex than that presented in the media.

Non-indigenous people from the cities related to bears in the 1950s in a way that we would find appalling by current standards (see appendix 3). The spotting of white coloured “Spirit bears” or “Ghost bears” is increasingly become a focus of the Tourist industry and sometimes the cause of a romanticized view of the natural world. We need to step back and think about how this behavior will be looked upon 50 years into the future

Appendix 1. Some Accounts of Bear Diversity on the Northwest Coast

David Thompson, while travelling in western Canada in the 1798-1807 time period noted that: “The only bears of this country are the small black Bear, with a chance yellow Bear, this latter has a fine fur and trades for three Beavers inbarter, when full grown” (Thompson 2009:122). He notes that the black furred bears trade for one or two Beaver skins depending on their size. As Thompson discusses the grizzly bear elsewhere, it appears he is referring here to the “yellow Bear” as a variation of the black bear.

Daniel Harmon was an early observer of bears in the Interior of B.C. In 1810, around Ft. St. James, he observes: “The brown and black bear differ little, excepting in their colour. The hair of the former is much finer than that of the latter. They usually flee from a human being. .. .The brown and the black bear, climb trees, which the grey, never does. Their flesh is not considered so pleasant food as the of the moose, buffalo or deer; but their oil is highly valued by the Natives, as it constitutes an article of their feasts, and serves, also, to oil their bodies, and other things. Occasionally, a bear is found, the colour of which is like that of a white sheep, and the hair is much longer than that of the other kinds which have been mentioned; though in other respects, it differs not at all from the black bears.” (Lamb 1957:260).

Black, travelling on a branch of the upper Stikine River on August 3, 1824, with an Indigenous Slave notes bears of a pale white colour. Black explains “there are Bears, Black, blue or Grizzly & brown of different shades & they all appear large, the Old Slave is by no means inclined to attach them, the other day Mr. Manson & the old Slave in Company saw two Bears of a pale white colour, but the old Gentleman would not consent to attach them, such is the Idea of these Indians regarding Bears” (Rich 1955:153).

Crompton, who travelled extensively in B.C. in the mid 19th century stated: “The black bear is subject occasionally to albinism like most for the other animals on this coast thus I have seen white (black) bears, white otters, white racoons, white martins and white minks. The Indians set a great value on the white bear skin & I was shown one which was supposed to be the paternal originator of the Tsimpsean race after the flood for their tradition of the deluge is that only a woman & a bear were saved on a mountain & that from this peculiar miscegenation the Tshimsean race arose.” (Crompton 1879:51).

Frederica De Laguna acquired information from both Indigenous and non- indigenous peoples in the territories of Tlingit peoples in the 1930s to 1950s, which shows the confusion of bear descriptions at the time: “The Yakutat people; face a variety of large brown bears and grizzlies. These have never been classified to the satisfaction of biologists, but for the native all these large species are “the bear” (xuts; Boas, 1917, p. 158, xuts), the prize of the intrepid hunter and an important sib crest. The very large, dark grizzed Dall brown bear, Ursus dalli, lives northeast of Yakutat Bay, especially along the Malaspin Glacier. The forester, Jay Williams (1952:138),

reports this huge bear at Lituya Bay, it may be another variety, or there may be a break in its distribution between Yaktat and Lituya Bays. Apparently confined to the south-eastern side of Yakutat Bay is the Yakutat grizzly, U.nortoni, a large true grizzly with yellowish or golden brown had and dark brown rump and legs, the whole looking whitish from a distance. It seems to range as far south as Lituay Bay (Williams, 1952:138). Also known at Yakutat is the giant brown bear of Kodiak, the Alaska Peninsula and Prince William sound, U. Middendorffi. The Alsek, U. Orgiloides, a cream-coloured medium sized bear with long narrow skull, ranges the foreland east of Yakutat, especially along the Ahrnklin, Italia, and Alsek Rivers. It is not known whether this bear, or the closely related Glacier Bay grizzly, U. Orgilos, is the form found at Lituya Bay. Between Cross Sound and the Alsek delta is the large Townsend grizzly, U. Townsendi, the exact range of which is undefined.

The black bear (sik), found along the coastal glaciers form Lituya Bay (or Cross Sound) northward to the eastern edge of Prince William Sound or Cape Saint Elias, is very much smaller than the ordinary American black bear. Furthermore, in addition to the usual black and brownish colors, many from the same litter are blue-gray or maltese. These are called glacier bears, U. Americanus emmonsii, formerly Euarctos emmon see or Ursus glacialis. The Indians make no distinctions, as far as I know, between the color variants, unless what Boas (1891:174) recorded as the “polar bear” (caq, i.e., cax) is really the blueish glacier bear. A few bones of the black bear were found in the site of Knight Island.” (Laguna 1972:36-37).

Appendix 2. Bear Traps and Indigenous Laws

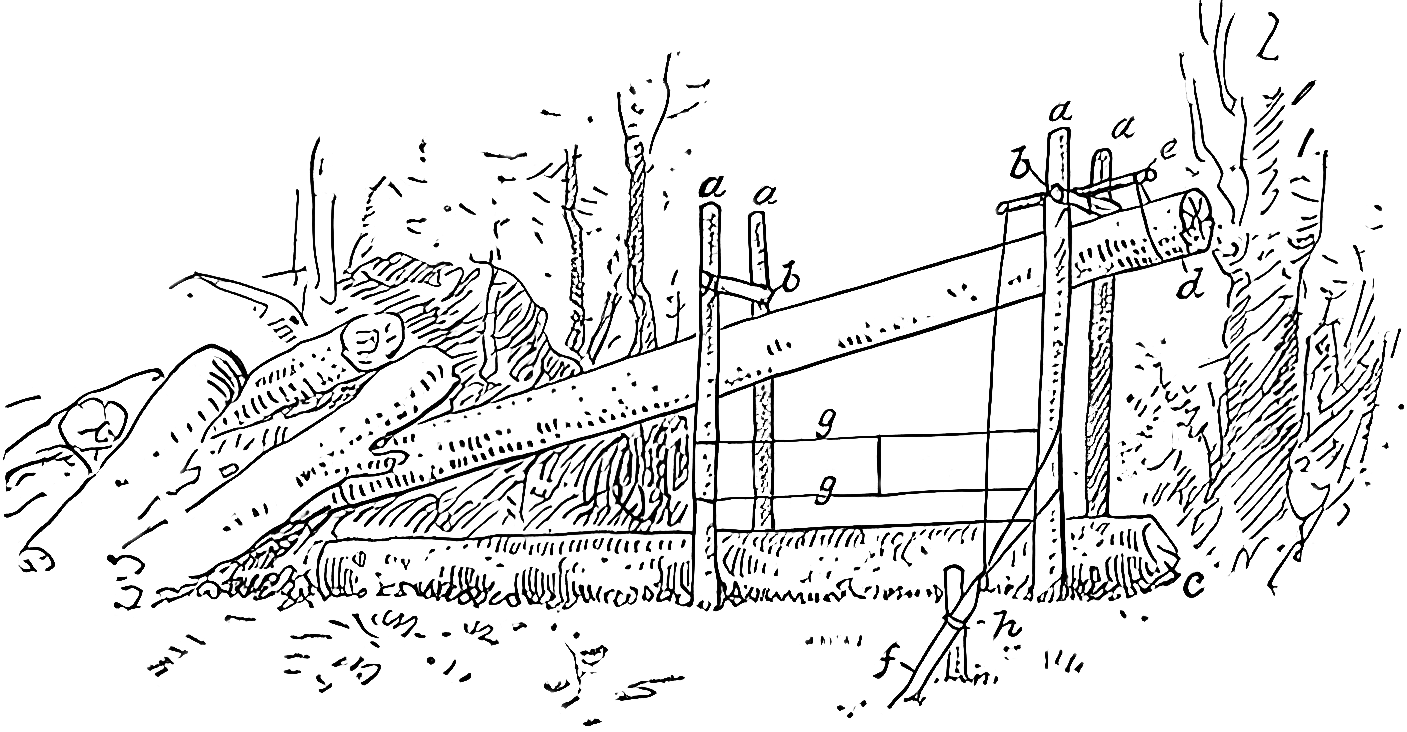

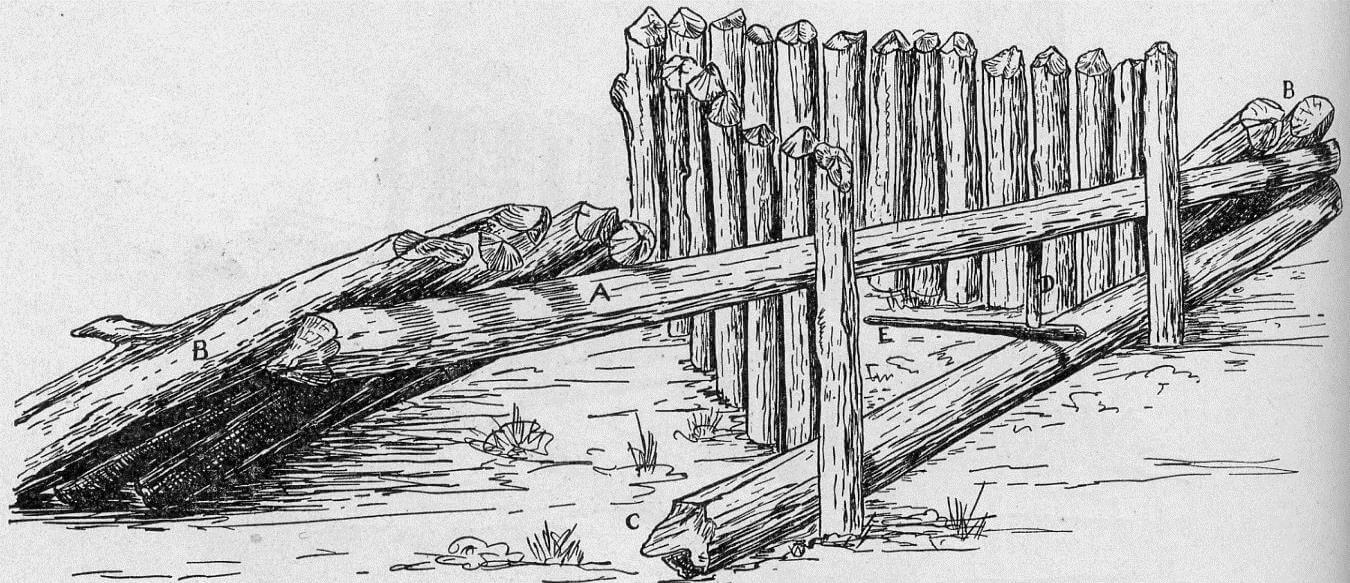

Swanton (1905:58-69) was told the story of a bear hunter and his traps by Haida, Jimmy Sterling. In telling the story he gets a detailed description of how the traps are constructed. Haida names were provided for each part of the deadfall trap.

In the Haida bear path deadfall trap shown in figure 9b, the letters indicate: A- Four posts, two on each side of the bear trail. B-Short cross posts tying each set of vertical posts together. C- Between the posts lays a post on the ground. D- The deadfall log that drops on the bear. E- The suspended end of the deadfall post is held by a loop which passes over a short stick E. Stick E is supported by post B. A rope is fastened to the inner end of stick E and carried down to a notched in stick F which is tied to a stake pounded into the ground on one side of the bear trail. Other cords G are fastened across the two front posts and down to the same loop. The bear steps over the log and comes against these latter cords causing the rope to slip out of the notch and the deadfall log to fall (Swanton 1905:6).

Koppert gives one of the better explanations of the use, design and traditional laws around the subject of bear traps or “Chim mis yek ”. Koppert was informed that, if one eats “bear meat or venison, one must abstain for two months from eating fish, especially salmon and halibut”.

In regard to the hunting grounds of bears: “There are no special districts set aside for hunting. Traps are set in places frequented by the animals. An Indian has full right to an animal trail as long as his traps are there. Once he removes his trap, any other Indian may put his trap there and claim all the animals on the trail. An exception to this law is made with regard to the bear trails. The bears are a very valuable animal to the Indians, and the trail is, therefore, owned by the individual whether he has his trap set or not. No one may hunt on such ‘roads’, even though no trap is set. Such bear trails, as well as creeks in which certain Indians have the sole right to fish with trap-boxes, are called ha-how- thle, meaning: belonging to so and so”. These (ha- how- thle) are inherited in the same manner as “house grounds”. They may, however, be ‘leased’, or given away and be lost forever to the family and descendants. A traveller may not take or capture an animal if traps are set in the vicinity.

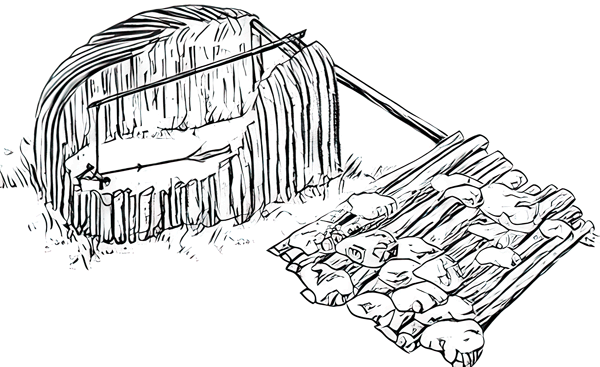

Koppert describes how bears are trapped in the following manner: “poles driven closely together into the ground near a stream where the bears follow the creek. These poles are about four feet high and arranged in a semi-circle with a diameter of about three feet [See Fig. 10]. The top and sides are covered with branches and sod to make the trap and ‘cave’ appear natural and to make the interior dark. The entrance, at the center of the semi-circle, is just large enough to admit the head and shoulders of the bear. Over the entrance are erected two uprights and a crosspiece. Resting on this cross-piece and projecting about six inches, is a pole reaching back to the farther end of the ‘cave’. A strong string is tied to the inner end of the pole and let down into the ‘cave’; three stakes are driven into the ground at the back of the ‘cave’; to the tops of these stakes and lashed to cross – pieces forming a V …the V is closed by a stick held in place by the pull on the cord which in turn is tied on the ‘tripper’; the ‘tripper’ suspends the weighted log at the entrance of the ‘cave’. To the same stick, a stout string is tied at the end of which is the bait of salmon. Above the entrance, a log is suspended by a thong from the end of the pole resting on the cross-piece. The log at the other end has a dozen or more other logs resting on the top of it as well as heavy stones. When the bear snatches the fish he releases the string that suspends the weighted log over the entrance, and is crushed under the weight of the fallen log. This effective dead-fall is still commonly used. It either kills the bear outright or so cripples him that he cannot run away.” (Koppert 1910:78-80).

In the type of trap shown in figure 10, the bear sticks its head into the cave-like structure and pulls the bait on the rope. The rope pulls a short post out from the edge of a rectangular structure that is holding down, by a rope, one end of a long pole that extends across the cave and over a post across the entrance to the cave. The other end of this post is tied to the large heavy deadfall log. The release of distant end of the long post causes it to flip up over the entrance post causing the deadfall log to come crashing down on the bear.

Father Morice wrote how the Carrier of the Interior began to ritually prepare “a full month previous to the settling of his snares. During all that time he could not drink from the same vessel as his wife, but had to use a special birch bark drinking cup. The second half of the penitential month was employed in preparing his snares. The omission of these observances was believed to cause the escape of the game after it had been snared. To further allure it into the snares he was making, the hunter used to eat the root o f a species of heracleum (tse’le’p in Carrier) of which the black bear is said to be especially fond. Sometimes he would chew and squirt it up with water exclaiming at the same time: Nyustluh! May I snare you! Once a bear, or indeed any animal, had been secured, it was never allowed to pass a night in its entirety, but must have some limb, hind or fore paws, cut off, as a means of pacifying its fellows irritated by its killing.

… The skulls of bears whose flesh had been eaten up are even to-day invariably stuck on a stick or broken branch of a tree. But the aboriginals fail to give any reason for this practice (Morice 1893:107-108).

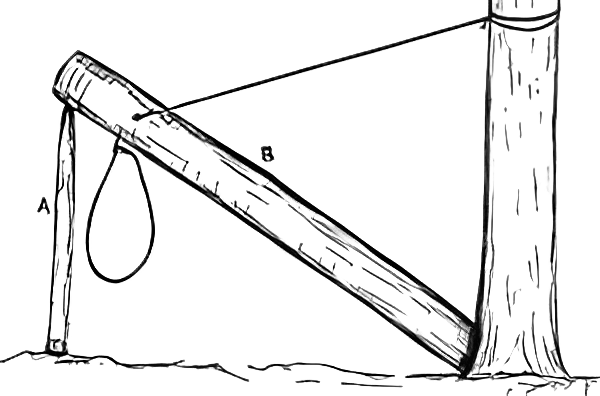

In the type of deadfall trap in figure 12, the bear crawls part way into the wooden structure to get the bait on the inner end of a bait stick. The outer end of this bait stick has resting on it a short post holding up the deadfall log. This upright support post is in a notch on the bait post. When the bear swings the bait post around the short upright support post slips out of its notch and causes the deadfall log to crash down.

Appendix 3. Humans and Bears of the 1950s

In the 1950s bears were often seen as entertainment animals with little understanding of their relationship to their natural habitat. As bears lost their fear of humans they mingled together (see figure 13). When I camped in Banff and Jasper as a child it was common to see large line-ups of cars on the highway feeding bears. Ice cream cones were their favorite treat. My father would drive us to the local open garbage dumps where large number of bears came at dusk (figure 14a&b). In one incident a large bear climbed up onto the front of our car and looked at us through the windshield. My father (not a “bear whisperer”) blasted his car horn causing him to be required to explain later how his company car received some very large scrape marks down its entire front. We know today that feeding of wild bears usually ends in them having to be shot. We need to continually educate people not to do this.

References

Cove, John J. and George F. McDonad (eds). 1987. Tricksters, Shamans and Heroes. Tsimshian Narratives I. Canadian Museum of Civilization. Mercury Series. Directorate. Paper No. 3.

Crockford, Susan J. 2006. Ryths of Life: Thyroid Hormone and the Origin of Species. Trafford Publishing.

Crockford, Susan J. 2003. Thyroid hormone phenotypes and hominid evolution: a new paradigm implicates pulsatile thyroid hormone secretion in speciation and adaptation changes. International Journal of Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A 135(1):105-129. ‘

Crompton, Pym Nevins. 1879. RBCM Archives Additional Manuscript 2778.

Natural History, pages 50-52.

Daily Colonist. 1911. Reports on Game Exhibit at Vienna. March 9:15.

Daily Colonist. 1912a. Ursus Kermodei. November 23:6.

Daily Colonist. 1912b. Will Pay $250 For A Kermode Cream Bear. Nov. 17.

Daily Colonist. 1905. Museum Curator Gets High Honors. February 1:9.

Daily Colonist. 1925. White Bears Capture Ends Savants Dispute. January 14:5.

De Laguna, Frederica 1972. Yakutat. Land and It Peoples. Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology. Vol. 7 part 1.

Emmons, George Thornton. 1991. The Tlingit Indians. Edited with additions by Frederica de Laguna and a biography by Jean Low. Douglas & MacIntrye, Vancovuer/Toronto. American Museum of Natural History, New York.

Emmons, George Thornton. 1911. The Tahltan Indians. University of Pennsylvania. The Museum Anthropological Publications, Vol. IV, No.1. Philadelphia.

Golder, F. A. 1907. A Kadiak Island Story: The White-Faced Bear. Journal of American Folk-Lore. Vol. XX. No. LXXIX, Oct. to Dec. pp. 296-299.

Hatler, David F. David W. Nagorson and Alison M. Beal. 2008. Carnivores of British Columbia. Royal B.C. Museum Handbook. Vol. 5. The Mammals of British Columiba. Royal B.C. Museum Victoria, Canada.

Hallowell. A. Irving. 1926. Bear Ceremonialism in the Northern Hemisphere. American Anthropologist. New Series 28:1-175.

Hedrick, Philip W and Kermit Ritland. 2011. “Population Genetics of the White – Phased ‘Spirit’ Black Bear of British Columbia,” Evolution vol. 66, no. 2.

Holzworth, John M. 1930. The Wild Grizzlies of Alaska. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, The Knickerbocker Press, New York.

Klinka, Dan R. and Thomas E. Reimchen. 2009. “Adaptive Coat Colour Polymorphism in the Kermode Bear of Coastal British Columbia,” Biological Journal of the Linnean Society vol. 98, no. 3.

Koppert, Vincent. 1910. Contributions to Clayoquot Ethnology. The Catholic University of America. Anthropological Series. No. 1. Washington, D.C.

Lamb, W. Kaye ed. 1957. Sixteen Years in the Indian Country. The Journal of Daniel Williams Harmon. 1800-1816. Edited with Introduction by W. Kaye Lamb. The MacMillan Company of Canada Limited.

Marshall, H.D. and Kermit Ritland. 2002. “Genetic Diversity and Differentiation of Kermode Bear Populations,” Molecular Ecology vol. 11, no. 4.

Maud, Ralph. 1993. The Girl Who Married the Bear and The history of Kbi’shount, pages 30-41. In: The Porcupine Hunter and other Stories: The Original Tsimshian Text of Henry W. Tate. Newly translated from the original manuscripts and annotated by Ralf Maud. Talon Books.

Merriam, C. Hart. 1918. Review of the Grizzly and Big Brown Bears of North America (Genus ursus) with Description of a New Genus, Vetlarctos. North American Fauna: February 1918, Number 41: pp. 1 – 137. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Bureau of Biological Survey. Government Printing Press, Washington.

Morice, A.G. 1893. Notes archaeological, industrial and sociological on the Western Denes: with an ethnographical sketch of the same. Transactions of the Canadian Institute, Vol. IV, part 1, no.7, 1892-93.

Niblack, A. P. 1889. “Ethnology of the Coast Indian tribes of

Alaska.” Proceedings of the United States National Museum. 11 (718):328.

Pocock, Richard J. 1909. Hunting and Fishing, Here and Elsewhere. Victoria Daily Colonist December 12, 1909.

Piero, Viscounti, Stewart H. M. Butchart, Thomas M. Brookes, Penny F. Langhammer, Daniel Marnewick, Sheila Vergara, Allberto Yanosky and James E.M. Watson. 2019. Science Vol. 364. Issue 6437:239-241.

Pike, Warburton Pike. 1910. The Big Game of British Columbia. The Victoria Colonist, Nov 13, 1910, p.6.

Puckett, Emily E., Paul D. Etter, Eric A. Johnson, Lori S. Eggert. 2015. Phylogeographic Analyses of American Black Bears (Ursus americanus) Suggest Four Glacial Refugia and Complex Patterns of Postglacial Admixture. Molecular Biology and Evolution, Vol. 32, Issue 9, 1 September 2015:2338-2350.

Rich, E.E. (ed), 1955. Black’s Rocky Mountain Journal. 1824. The Publication of the Hudson’s Bay Company Record Society, XVIII, London.

Reimchen, Thomas E. and Dan R. Klinka. 2017. “Niche Differentiation between Coat Colour Morphs in the Kermode Bear (Ursidae) of Coastal British Columbia,” Biological Journal of the Linnean Society.

Ritland, K, C. Newton and H.D. Marshall. 2001. “Inheritance and Population Structure of the White-phased ‘Kermode’ black Bear,” Current Biology vol. 11, no. 18.

Provincial Museum. 1909. Provincial Museum of Natural History and Ethnology. Victoria, British Columbia. Printed by Authority of the Legislative Assembly.

Printed by Richard Wolfenden, L.S.O., V.D, Printer to the King’s Most Excellent Majesty, Victoria.

Sapir, Edward 1915. A Sketch of the Social Organization of the Nass River Indians. Canada Department of Mines. Geological Survey. Museum Bulletin No.19. Anthropological Series, No.7. October 15, 1915. Ottawa. Government Printing Bureau.

Swanton, John R. 1908. The Story of the Grizzly- Bear Crest of the Te’qoedi. Tlingit Myths and Text. Smithsonian Institution. Bureau of American Ethnology. Bulletin 39. Washington D.C.

Swanton, John R. 1905. A Story Told to Accompany Bear Songs. Haida Myths and Text. Skidegate Dialect. Smithsonian Institution. Bureau of American Ethnology. Bulletin 29, Washington D.C.