By Grant Keddie

Introduction

Sling stones were used in warfare and for killing small mammals and birds throughout many parts of the world. Their use in warfare on the Northwest coast has been underemphasized. Figure 1, shows some of the many sling stones I collected at the base of an Indigenous defensive site, DcRu-123, at Lime Point in Victoria Harbour (Keddie 2023).

Sling stones are often difficult to identify in Archaeological sites because they are not intentionally shaped by people and therefore not easy to identified as sling stones. The context in which they are found is important to provide clues that they were used as sling stones. In the case of Lime Point, they were highly concentrated just above the bottom of the site and included a variety of types of uniform rounded stones that were not like bedrock material and not found in any of the local beaches. These were carefully selected for their size from beaches at other locations. I correctly predicted that similar sling stones would be found behind stone wall defensive locations along the Fraser River – that were later excavated.

The authors stone-throwing sling shows how one strap is tied around the middle finger while the loose end. with a knot, is held in the same hand for quick release – after several swings of the sling (Figure 2).

Sling Stones in War

The first observation of the use of slings by Indigenous people in British Columbia occurred in July 1788. John Meares anchored his boat, the 200-ton Nootka, near the entrance to Juan de Fuca Strait and sent his long boat on July 13th with 13 men to survey the Strait for a month.

Where Meares longboat went is a subject of controversy. He claimed to go as far as “30 leagues” up the Strait, but clearly falsified this information. The evidence suggests that his ship did not go further than Port San Juan (at todays Port Renfrew) across from Cape Flattery (see Howay 1969). The longboat may have gone further up the Strait, if it is true that it was gone for a week when it returned.

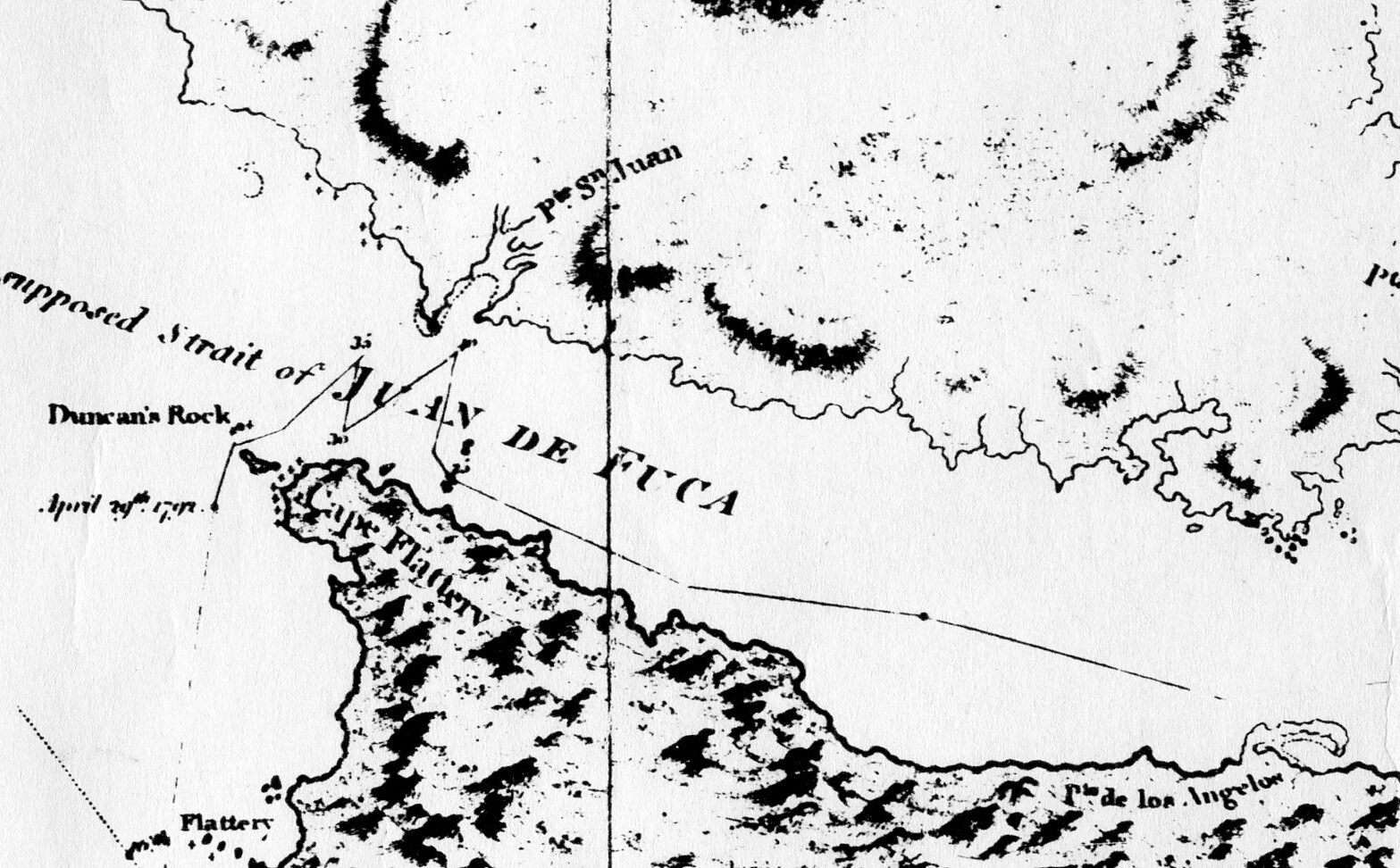

The map of Captain Vancouver’s crew surveyed after he entered the Strait in 1792 ( Figure 3) shows Port San Juan on the north side of the entrance. The map features on the north side of the Strait are a product of information from earlier Spanish surveys. Sooke Inlet can be seen to the right on the north side of the Strait.

Meares Story

Meares wrote: “the boat had advanced a considerable way up the Straits of Juan de Fuca and entered a bay or harbour, when our people were preparing to land for the purposes of examining it, they were attacked by the natives” (Meares 1790).

“They boarded the boat, with the design of taking her, in two canoes, containing between forty and fifty men, who were most probably some of their choice warriors. Several other canoes also remained at a small distance, to assist in the attempt; and the shore was everywhere lined with people who discharged at our vessel continuous showers of rocks and arrows. A chief in one of the canoes, who encouraged the advance of the others, was more fortunately shot in the head with a single ball, while in the vary act throwing a spear of a most enormous length at the cockswain. This circumstance caused the canoes to draw back, and deprive the natives who were already engaged, of that support which must have ensured them the victory.

Indeed, as it was, when we consider that the boats company consisted only of thirteen men, who were attacked with the most courageous fury be superior numbers, and galled as they were, at the same moment, by the numerous weapons constantly discharged from the shore, their escape is to be numbered among those favourable events in life”.

Meares noted, after the boat returned on July 20, from this “very violent conflict”, that Robert Duffin, the first officer in charge, was wounded with an arrow in his head and others had an arrow in the breast and calf of the leg:

“The rest of the people were bruised in a terrible manner by the stones and clubs of the enemy; even the boat itself was pierced in a thousand places by arrows, many of which remained in the awning that covered the back part of it; and which by receiving the arrows, and breaking the fall of large stones thrown from slings, in a great measure saved our party from inevitable destruction” (Meares 1790).

Slings in the Mythology

Anthropologist Franz Boas noted that in the Tsimshian story of the supernatural Prince Tsauda there “was a sling-throwing contest with his slave Halus who married into the same high-ranking family. Halus married the daughter who was originally to marry Tsauda.

Tsauda blew water out of his mouth and caused Halus’s sling-stone to pass through his mother-in-law’s lip hole. The mother-in-law was ashamed, not solely because of the violation of her body but because metaphorically the removal of the labret represents the ultimate insult to her lineage by the marriage of her daughter to a slave. The labret protects the orifice to her spiritual being which gives her the inherent status represented by the labret. The removal of the labret is the symbolic removal of her status.

The slave Halus’s wife died and was reincarnated as the daughter of Tsauda. When born, the girl had “four holes in each ear and a hole in her lip and in the septum of the nose, as a sign of her high rank.” Her husband became “the first copper-worker among the natives” and the richest chief (Boas 1916:297-306). The hero of the story kills a double headed dragon and uses his eyeballs as sling stones (Boas 1916).

In another Tsimshian, story told by Philip Moses, called The Stars, a man who shot a string of arrows to the sky hole climbed up to rescue his boy who Star had capture. In the rescue his father carried on him “tobacco, red paint and sling-stones” which he used to bribe a man in the sky to find his son. When making their escape from Star’s tribe these items were thrown in their way to stop them. The father and son climbed down the arrows and made it back to earth (Boas 1902).

The Ethnological Record

There are many ethnological summaries of various weapons used for hunting both humans and other animals, but very few on the subject of sling stones. Many war stories involve the use of guns, where the effectiveness of slings may have been lessened with the ability of warriors to shot from further away. Indigenous knowledge of slings used in warfare seems to have disappeared by the 1860s.

De Laguna, in spite of her extensive documentation of warfare and weapons by Indigenous Tlingit consultants, noted that she “could not discover” whether the sling and sling stone were ever used in war (de Laguna1972).

Slings and their use are mentioned in Indigenous stories, but there are limited observations of their use for other purposes in historic writings. One interesting early observation was made in 1805, regarding the making of slings by women. Von Langsdorff observed women making “slings and fishing hooks” among the people of Kodiak Island (Langsdorff 1968).

Suttles provided an account of Semiahmoo, Julius Charles (born c. 1865) which included the usual general reference to hunting birds, but not for warfare:

“Boys and grown men as well used a sling … for throwing rocks at waterfowl from the shore. It was simply a diamond-shaped pocket of hide with a line at each end. Round beach rocks were chosen because they flew straighter than flat ones. The little snipes (least sandpipers?) could be killed just by throwing a four-foot stick into a flock” (1951).

This author had a similar experience to the latter with prairie grouse as a child around 10 years old. We leaned where the grouse would fly to next when we chased them up from a specific direction. Some of us waited ahead in the grass where they were headed and threw old hardwood chair legs swinging directly into them – knocking them down.

I would suggest that it was likely that both women and older children played an important role in defensive warfare, along with men, by pelting approaching canoes with rocks in the same way as described above in 1788. I would also suggest that throwing of fast rotating hardwood sticks into a crowd of attackers, from a defensive wall, my have been effective in the same way as hunting throwing sticks used by Indigenous peoples of Australia.

References

Boas, Franz. 1916. Tsimshian Mythology. Thirty-First Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology. To the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. 1909-1910., Government Printing Press, Washington.

Boas, Franz. 1902. Tsimshian Text. Smithsonian Institute. Bureau of American Ethnology. Bulletin 27. Government Printing Office, Washington.

De Laguna, Frederica. 1972. Under Mount Saint Elias: The History and Culture of the Yakutat Tlingit. Part Two. Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology, Volume 7.

Howay, Frederick W. (ed). 1969. The Dixon-Meares Controversy. Bibliotheca Australiana Extra Series. N. Israel/Amsterdam, Da Capo Press, New York.

Keddie, Grant 2023. The Lime Bay Indigenous Site. (This web site. grantkeddie.com).

Meares, John 1790. Voyages Make in the Years 1788 and 1789. From China to the North West Coast of America. Logographic Press, London.

Vancouver, George. 1798. A Chart Showing the N. W. Coast of America with the tracks of His Majesty’s sloop Discovery and Armed Tender Catham: Commanded by George Vancouver. May 1, 1798. J. Edwards Pall Mall & G. Robertson, London.

Von Langsdorff, George H. 1968 (1814). Voyages and Travels in Various Parts of the World. Part II. Republished as Bibliothec Austraiana #41, N. Israel and Amsterdam, Da Capo Press, New York.