By Grant Keddie. March 2023.

Introduction

The rigid distinction between culture and nature in historic western societies did not exist in Indigenous cultures. Animals were not just sources of food and raw materials but intelligent sentient beings as conscious and capable of understanding as humans and as capable in undertaking planned intentional activities.

Symbolic presentations of animals or supernatural beings in both material artifacts and mythology, such as Thunderbird in his various transformations, are about relationships between what we see as the social world and natural world. In the indigenous cosmologies beings such as Thunderbird play a role as active participants in ecological relationships.

Anthropologist Franz Boas felt that myth adjusts to the world and that it supports existing institutions (Boas 1898:16-17). Designs reflect mythology that has a function in the society that espouses it. Mythology can be adapted from outside and serve a function – with some elements taken out and others added. Mythology: “bringing out those points which are of interest to the people themselves” (Boas 1916:393).

The world of art history has struggled with the problem of how to define art in indigenous societies in relation to that of the western world. There are two aspects of what we call art in the modern world that I will focus on here. One of the important considerations is that art expresses a meaningful system of relationships and is a representation of cultural philosophy.

Here I will not use the term “art” in referring to the subject matter of traditional spindle whorl designs, but the term iconography. Iconography is the subject matter or content of works of art, as opposed to their form and technical function – although these are integrated into the larger picture. When looking at the content. I am not asking the question – what does it mean? I am asking what is the expressive or communication medium. Following the ideas of Gell (1998), it is clear to me that the images on spindle whorls are made to be seen. They are a reflection of social relations. One can undertake an analysis of the patterning of images on objects to understand social purposes.

Gell defines art as: “a specialized form of material culture or technology whose particular purpose is to provoke a socially desired response. Art acts upon people. Imagery can serve many purposes (1998)”.

One, of course, needs to know what the images are. Imagery depicts a subject – often humans and other animals, supernatural spirit creatures, and their states of transformations. In the Northwest Coast cultural area social relations are expressed in the iconography on many material objects. On the southern coast of British Columbia images are on some spindle whorls, some blanket pins, some rattles, some house posts, some bark beaters and shredders, some boxes, some clubs and many other things.

These are not just decoration but images that had social secular and religious meanings. Representations of spirits made the world of supernatural spirits visible in the present.

The imagery of spindle whorls is about the prerogatives of the uses and their connection with the supernatural. A spinning whorl could be conceived as a visual transformation into another world. Anthropologist Wilson Duff speculated that the spinning of the image on the whorl is like the experience of a trance (personal communication). I would speculate that a moving spindle with a Thunderbird motif may be seen like the flight of a bird – and like shooting stars can become seen as a living entity. But we cannot know if these ideas formed the visualizations of indigenous people that were part of that earlier world.

The Sources of the Iconography

In order to understand what underlies imagery on the Northwest Coast we need to understand the nature of animistic cultures from which they have undergone their transformations.

The iconography of the Northwest Coast distinguishes individuals, families or populations as those with a history and those with special powers. I would infer that spinning and weaving are one of the contexts in which these powers are displayed and validated.

Rozwadowski, in giving examples from the animistic cultures of Siberia, notes that much of the imagery reflects ideas about the relationship between the living and the dead. In a focus on “rock art” he points out that rock art can be seen as “a veil beyond which the other world could be encountered”. The images of a rock surface are a reflection of another world that lies beneath (Rozwadowski 2017) .

Similar rock art imagery and practices extend around the Pacific Rim. Although one needs to be leery of making historic connections with distant cultures of the past, concepts such as those surrounding supernatural beings, have some long lasting similarities that transcend regional boundaries.

Petroglyph sites and carved images are often linked to the activities of shamans, but as Hill points out focusing on the role of shamanism “obscures the roles of hunters and their wives. Their thoughts and actions established and maintained relationships with prey animals and may be more productively conceptualized as dynamic social behaviours embedded within the context of daily life than as privileged ritual acts” (Hill 2011).

Carved Images can be seen as integration between humans and what they represent. The images may be seen as a veil into the other world and the owners connected to it – a connection with the other world of the supernatural.

This imagery can be a servant of social class or religion. Crests are social symbols “to make the social system visible by providing emblems to distinguish the different groups and to symbolize their privileges” (Kobrinsky 1980).

As Kobrinsky summarizes in another context:

“Special individuals, successors of animal and human Ancestors, are set apart to carry the diminished aura of mythic quasi-oneness through time by means of supernatural communions. Within the human social order, this is the religious origin of caste: the presumed limitation on the communions of men and spirits diminishes the communions of men; special privilege, in economy as in ceremony, is thus conferred upon the spiritually blessed” Kobrinsky (1979).

Perception varies according to context and culture. Deregowski has shown that: “there are persistent differences in the way pictorial information is interpreted by people of various cultures” and that “perception of pictures” calls for some form of cultural depended learning (Deregowski 1972:82).

There are cultural conventions for depicting the spatial arrangement of three dimensional objects. As Gell puts it: “Looking at images is culturally specific, learned and semantically embedded in concepts of social relationality and power” (Gell 1998).

Thunderbird images are not just decorations but images that had social and religious meanings. The imagery seen on many spindle whorls is that held by selected families. Families that have the powers of the Thunderbird complex – the Thunderbird, the Sisuitl, Haietlik and Sinulkey versions of the Lightning snake, the Thunder and the Wirlwind. As Lane indicates among the Cowichan: “For practical purposes inheritance of power occurs in family lines, although the cultural fiction is that it is not” (Lane 1951).

Those who spin with the power of Thunderbird can create the material for blankets, the material for wealth. If a person finds the bone of a lightning snake cast down by the Thunderbird, the finder: “possesses one of the most powerful of charms” (Boas 1889:596).

The Nature of Coast Salish Iconography and Its Context

Spirit Powers

Salish art is religious iconography that is often based on the personal knowledge of the supernatural gained through the spirit quest. Most carved images come from direct experience of the vision quest by an individual or someone in their family in the distant past. All special skills that a person has are believed to have come as gifts from visions.

Spirit helpers gave power to be good sealers, deer hunters, fishermen or gamblers. Powers were also held as family possessions that were passed down to family members who knew the proper ritual spells and who undertook the proper ritual cleansing activities to be worthy of receiving those powers.

If a family was empowered to use a particular cleansing rite involving fisher skins, its house posts may be decorated with carvings of this animal – it is a public statement of the family’s importance in having a wealth of ritual knowledge.

Franz boas indicated that families “of standing” on the Fraser River Delta possessed their own crest or crests: “These are more or less conventionalized representations, plastic or pictographic to have come down from the founder of the family group. These totems are looked upon as spirit guardians of the house hold, representations or symbols of them being carved or painted on some portion of the family dwelling, usually upon the supporting pillars of the roof, among the Island tribes” (Boas 1906:229). He observed that one of these “totems” were customarily carved on the face of main pillars in high relief and “represented the family or Kin-group totems, – the presiding, protecting spirits of the household” (Boas 1906:232). Not all of the tribes on the lower Fraser River held the same beliefs. In the late 19th century, Hill-Tout observed among the Kwantlen that he was: “unable to discover anything like a developed totemic system among them. As among the Chilliwack, it was customary for everyone to seek personal sulia [spirit power]. They had both personal and family crests” (Maude 1978:71).

Masks and rattles were used in cleansing ceremonies at weddings, funerals, births and changes in name. It was at these times that people were believed to be susceptible to harm from the spirit world. Much of the Coast Salish carving is funerary sculpture. The largest sculptures were posts for the mortuary houses in which the dead were place for the first year or so. Effigies of the dead would be shown at a second year funeral and carved figures placed on family tombs in which the newly cleaned bones would be finally placed. Carvings that involve connections with the supernatural appear on personal items such as rattles, blanket pins, combs, mat creasers and spindle whorls.

In examining these objects, one needs to be aware that the objects or their designs may have originated from places other than where they were collected. The designs on a mountain sheep horn rattle collected in 1778, by James Cook is assumed to be a product of Salishan speakers, but was most likely collected from Yuquot on the west coast of Vancouver Island – as Cook did not visit the territory of any Salish language family speakers (see Figure 7a&7b). This type of rattle was used on the south east coast of Vancouver Island and southwestern mainland as one of the ritual cleansing items used in the Sxwayxwey ceremonies. It has Thunderbird and salmon designs similar to those seen on later spindle whorls from the latter area (figure 8a&b).

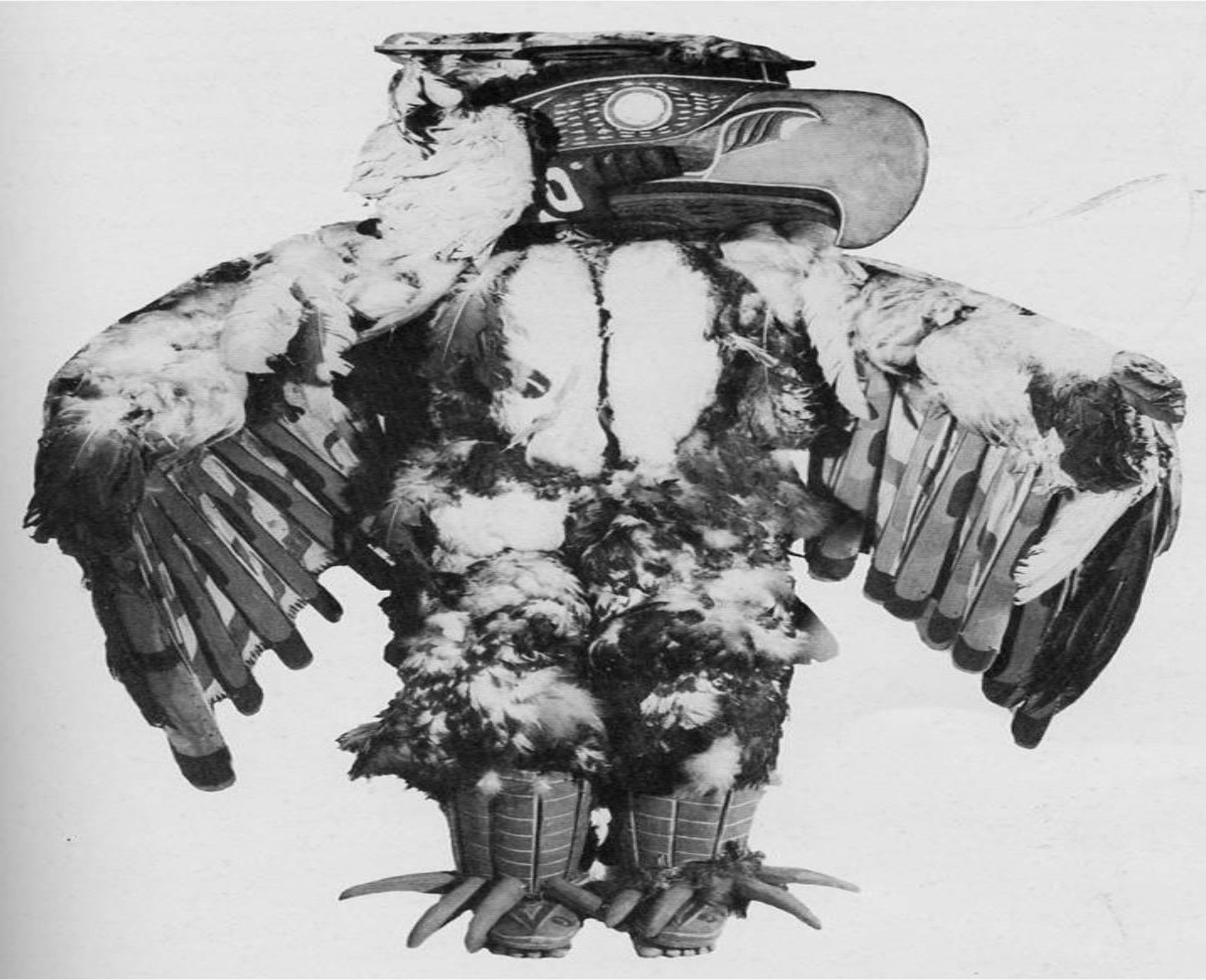

I see much of the iconography on the large spindle whorls of the historic period as being a statement about social organization and associated with what I am calling the Thunderbird Complex – that is iconography that is an expression of the supernatural human who wears a bird costume and is seen in its many forms in transformation and linked to the various forms of dragon-like lightning snakes (Figure 1).

The Thunderbird Complex

What I am referring to here as the thunderbird Complex is all the cultural material that pertains to the large bird/human of Northwest Coast legend that held dominion over the earth, waters and sky. Stories about it are held among First Nations from Alaska to Washington State and beyond to the east and across the Bering Strait.

There are regional differences, but one can generalize from the numerous stories that the thunderbird lived on the top of various high mountains. He swept down and picked up a whale from the sea, carrying it to his nest. His outspread wings shadowed the heavens and caused by their flapping the rolling of the thunder. The flashing tongue or eye of the Thunder Bird created lightning, and his feathers spread the rain from a lake on his back. Lightning was caused by ruffling feathers or throwing down the lightning snake which he tied as a belt around his waist or tucked under his feathers. Lightning snakes could transform into salmon.

In the iconography of the Nuu-chan-nulth people on the west coast of Vancouver Island, the trilogy of the Thunderbird, lightning snake (Haietlik) and whale form prominent figures on house fronts, screens, boxes and other cultural artifacts (figure 9) and similar Kwakwaka’wakw themes (figure 10).

The man who could overcome fear and, by watching the heavens in storm, observe the Thunderbird in flight, would rise to great distinction among his people. While he who by courage would climb the difficult slope to the mountain home of the Thunder Bird would achieve fabulous wealth (Boas 1910; 1921; 1935; 1938; Newcombe 1931; Adamson 1934; Ravenhill 1944).

The symbolism of the Thunderbird complex was the prerogative of those people whose ancestors gained the rights to use their supernatural powers and the right to tell the stories of how those powers were obtained.

In the story of The Thunders, John Swanton records about four brothers looking for their lost sister. They left their village and “they became the Thunders. When they move their wings you hear the Thunder, and, when they wink, you see the lightning”. People at the village were starving, so they flew out and “caught a whale and brought it to the town that it might be found next morning.” (Swanton 1909).

In a description of a Thunderbird mask, the field notes of Samuel Barrett indicate that: “There are said to be several kinds of thunderbirds, of which this is one. …He came down from the sky to gamble with humans and brought gaming stones” (1915:93). This connection with gambling and wealth is seen in the story of Thunderbird among the Ma’maleleqala Kwakwaka’wakwa where Thunderbird as the chief of Thunderbird Place, said: “Let us play with the people at Crooked Beach with my rainbow gambling stone and mist- covered gambling stone” (Boas 1902:295). The people of the village were “blown away with the wind made by the lightning of Thunderbird” (Boas 1902:299). In reference to another Thunderbird mask it was said: “this is a Thunderbird mask, but does not actually represent the bird as does a regular mask used in ceremonies. This one is worn, simply to show that the wearer’s ancestor came from the Thunderbirds” (Barrett 1915:52).

Among some speakers of Salish languages, stories of Thunderbird revolve around the negative aspects of the powers of individuals and their being overcome by others. One story was told by Songhees Tom James (“Whyuctan Swalamesett”) pertaining to the region around ‘Taatka’ where his family came from. This story was translated by Martha Douglas Harris (a daughter of James Douglas). In her, Scallighan: Or, The Thunder and Lightning Bird. Indian Legends, the story was told about a young man on Valdez Island who grew up to have special powers. He appeared to people at night as “shining light”. He had a house built of bullrush mats on top of Mount Tuam on Salt Spring Island:

“He said that the last day he wandered by himself in the forest, a monster bird, or Thunder, had carried him away, and that the bird had taken his eyes out and changed them, and had called him ‘Scallighan’, which means ‘I am a great man – I have great powers and rule the spirits.’ If he opened his eyes lightning would strike and kill people and if he took off his hat thunder would come”. He forced others to give him their daughters until he acquired 200 wives. Two brothers who lived in Cowichan attacked Scallighan and killed him with magic swords made out of elk antler. Scallighan’s spirit then “flew off as a great bird” and those who killed him released all the wives from this huge lodge, so they could all go back to their old homes (Harris 1901).

Another Cowichan version of this story was told later by Mary Rice (Tzea Mnteaht) in The Origin of the Thunder Bird. In this story a boy was born with special powers of having burning eyes. He saw a “great bird” in a dream who instructed him how to use his special powers. By removing his hat he could create thunder and shoot lightning from his eyes.

When the boy with the lightning eyes grew up he used his powers to abuse other people until his own people killed him. When he was killed: “as the last breath went from his body a great bird flew from the house, carrying his spirit away in to the skies. And that is how the thunder and lightning bird came to our land.” (Cryer 1936).

Some spindle whorls are representations of only Thunderbird(s) in their bird form. Figure 11a, collected at Cowichan by Colliard in 1927 (RBCM10270); Figure 11b. Eye of Thunderbird has an abalone inlay. Collected by John Humphreys of Chemainus before 1903. (FM A108064c); Figure 11c. Thunderbird. (Smithsonian 221179-B).

Figures 12a&b, shows similar whorls with pairs of Thunderbirds facing each other and circling: Collected at Quamichan in 1917 (RBCM2906) and Squamish collected before 1944 (Burke Museum 1-276; Dia: 19.5-20.2cm).

Interpreting the Thunderbird Complex Iconography through Myth.

In the languages of indigenous peoples of the Northwest Coast there were words that made a distinction between stories and myths. Myths referred to a pre-existing world that was different than the one we live in now. Myths explain how this already existing world was changed into the world of the present.

Collectors of spindle whorls often referred to the images as “bird” or “man and unidentified animals” or guessed what the animals were as real animals rather than gaining the indigenous name of various supernatural beings.

There are few direct indigenous interpretations of the large spindle whorl images other than occasionally giving them an English name such as “Thunderbird” or making general statements such as man and various animals – but, explanations are present in the rich mythology.

Myth can guide us to conclusions about symbols – they can be seen as interpretations of symbols. Myths can inform us about: (1) What the images are. (2) What the images mean. Oral histories, especially family legends where the story teller has the rights and knowledge to tell the story are the most valuable sources. Boas notes that myth provides: “a picture of their way of thinking and feeling will appear that renders their ideas as free from the bias of the European observers as is possible” (Boas 1935). The framework I am using to come to my interpretations is the blending of mythology and traditions with images. The patterns are reflected in the images.

An image on a spindle whorl of Thunderbird with a human face on its wing is likely a reflection of the stories that tell of how the owner’s ancestors first encounter with Thunderbird involved him being tucked under the large bird’s wing and flew them up into the sky. The alternative would be to show the human element of the transformer bird (see figures 2 & 3). The images are the stories of the ancestors encounters with thunderbird and how they gained their special powers.

As Cove explains “Symbols are central to how most people come to understand their being in the world … recognizing that the problem is in our relation to symbols, and not in symbols themselves” (Cove 1987:26-27).

Symbolism on objects such as spindle whorls, rattles and clubs reflect powers of owners. The stories linked to them connect the owners with their ancestors and how those powers were obtained in the distant past. An obvious example is the use by warriors of Thunderbird images on war clubs among those families whose had acquired the Thunderbird power. As Cove points out: “the past is used to define the present or a transformation from an earlier state of affairs” (Cove 1987:29).

In examining Indigenous images some appear as humans and some as other animals, but many linked in relation to these are beings in transformation. On the northern coast of British Columbia there are known stories associated with the acquisition of many symbolic crests. Every family or house crest once commemorated a history describing experiences such as an encounter with a member of a non-human species or supernatural being. On the southern coast, where the Iconography is more often lacking a known detailed history, one can see that much of the imagery is highly suggestive of human interaction or transformation with a non-human or supernatural beings. As Gell indicates: “Looking at images is culturally specific, learned and semantically embedded in concepts of social relationality and power” (Gell 2018). In trying to identify the content of whorl images the place to look is the knowledge imbedded in the Indigenous Mythology.

Thunderbird is a Man/Bird Transformer

Thunderbird is a man: Kwakwaka’wakw Dan Cranmer told a Nimkish story of a man that transformed from a salmon to a man. This man was building a house when Thunderbird came and helped him lift a house beam. The man said: “Oh, indeed, supernatural spirit, I have you for a treasure”. The Thunderbird “lifted his mask and spoke, …took off his Thunderbird dress” and made it: “fly away and it returned to where it came from above” (Boas 1938:85).

A long version of this story is told in the family histories recorded by Boas. A man found his “treasure” or spirit guide in a Thunderbird that was sitting on a rock nearby. The Thunderbird spoke to him: “O friend! Why do you come here walking?” The man replied: “I came to obtain you, Great Supernatural- One, as a treasure”. The Thunder bird said: “Come sit among the feathers of my wings, that we may go and see our world”. The man went up to the wings and sat among the feathers at the base of the wings; …when seated among the feathers the Thunderbird flew up”. After the Thunderbird flew back to the rock where he was first seen (Boas 1921:1129-1130).

George Hunt makes reference to a version of this story when providing information on a Thunderbird mask, number 1952, in the RBCM collection (figure 14). When building his house a man looked at the Thunderbird sitting near and said: “I wish you were a man so that you could help me”. The Thunderbird threw up his beak and said “What am I? I am a man”. He then sent his bird costume up into the sky and stayed behind as a man (Hunt 1922:2).

Acquiring Thunderbird as a spirit power

Boas recorded a Pentlach story of two brothers that climbed up to the mountain home of the “Thundergod”. The Thunderbirds took off their double headed snake belts and assumed human form. The descendants of the men gained the Thunderbird mask dance and the ability to see the Thunderbird (Bouchard and Kennedy 2002:239).

Whales are the salmon of the Thunderbird

The iconography of some spindle whorls show the Thunderbird man with salmon instead of whales. They are, however, the same entity. Whales are the salmon of the Thunderbird and the lightning snake can become salmon. This is made clear in the Mythology. Thunderbird dropped the double headed serpent on the ground and it became a salmon. It is noted: “the pole from which the Thunderbird watches for his salmon – whales and serpents” (Boas and Hunt 1902:189; 282-283).

Figure 15, shows what I interpret as the Thunderbirds catching their whales in the form of salmon. Lightning snakes can be seen at the base on the two left whorls. All of these whorls came from Cowichan on Vancouver Island and where all collected around the same time in the 1920s. They may have been then contemporary items made by Indigenous people to sell to collectors. Two of these were collected by George Emmons and three of these from the Newcome collection purchased from two earlier private collections.

Upper row: RBCM10692. Collected by Punnett pre-1961; RBCM10352 collected by Colliard 1927. Lower row: AMNH. 161_1865 Collected by Emmons 1929; Cowichan – Emmons 1929; CA 1954.130; RBCM10503 Collected by Colliard 1927.

Salmon are the dominant designs on all six spindle whorls shown in figure 16. These were all collected from Cowichan on Vancouver Island. A lightning snake can be seen hiding in the one at the lower right. Lightning snakes are known to disguise themselves as salmon.

An individual may recognize an image as Thunderbird, but not know the story of Thunderbird, the telling of which would be the prerogative of those families with the Thunderbird crest and that have special powers related to the Thunderbird and its associated powers of the Sisiult, Thunder or the Whirl Wind.

Designs related to person power acquired by spirit encounters effect a basic belief in gaining powers to control the world around them. It may be the power to be a skilled weaver or the power to bring in fish.

The Thunderbird as Whale Hunter

The content of stories about thunderbird among speakers of Salish languages does not usually include whale hunting. An exception is in the mythology of a Thunder story of the Lower Chehalis of Greys Harbour, Washington, where five Thunder brothers were chased by “dangerous being”. Although the Chehalis were not whale hunters in post contact times they mixed on reserves with their northern neighbours the Quinalt who were the most southern whale hunters in historic times (Adamson 1934).

However, Archaeological evidence has now show that whale hunting was once practiced on the Oregon coast at the Par-Tee site between about 1300 to 1600 years ago. A bone point made of an elk bone was found lodged in the skeleton of a humpback whale ( Losey and Yang 2007).

Another exception is a Cowichan story, told by Able Joe. This story does not involve the Thunderbird but his “younger brother” a Sinulkey – a creature who among the Salish language family speakers refers to a flying lightning snake who lived mostly in lakes and sloughs. This being flew down from his cave on mount Tsohalem and picked up a whale and took it back to his cave. As a result, all the salmon then began to travel up the Cowichan River providing food for the Cowichan people forever (Rosen 1978:26). In later times the Cowichan had what they called a “whale dance”.

The Sinulkey version of the Lightning Snake

On the southern coast among speakers of Salish languages there was a doubleheaded and a single headed “snake-like”, “lizard-like” or “dragon-like animal. These were given different names and a variety of characteristics by different populations. The former was called Sinulhkey or Seel-kee by some and Aix by others. The latter was known as Tcinakwa in the south and Tcinko or Stsinga in the north. Both were “whizzing, whining, flying beasts” that lived mostly in lakes and sloughs and sometimes appeared on land. Both of these “serpents” had scales.

Some First Nations consultants described them as having small feet; others said that they had wings; still others described them as having horns or a mane. One form was associated with lightning. When it was pursued by the Thunderbird it split rocks and trees when it struck them and left scales and bark lying about. This was referred to as the serpents trail. The scales and bark left by it were dangerous for the layman to touch.

If a ritually unprepared person saw a lightning snake or even crossed its trail on land, his arms, legs, and neck contorted in spasms and he died. The creature was usually seen when a person was in voluntary seclusion in the woods, searching for a “power” which would become their “guardian spirit”. This mythical serpent gave power almost exclusively to shamans who undertook special training and knew the rituals to overpower it. (Barnett 1955:147-153; Mathews 1955:15-16; Well 1970:25-31; Marshall 1999:15-21).

A Saanich man, Christopher Paul, told how the thunder over Saanich Inlet was the result of the fights between the thunderbird and the Sinulhkey. The local Malahat Mountian named Ya.s: “was the home of the legendary rainmaker, sinulkey, a four-legged serpent-like creature. To bring rain, one had only to point at ya.s” (Hudson 1970:2-3).

The Widespread Tradition

Flying reptilian-like creatures are wide spread in the stories of Indigenous peoples on the Northwest Coast. Lightning snakes are linked with Thunderbirds as their lightning bolts for killing whales in some regions and as lake monsters in other regions – the latter especially among some Salish language family speakers. These have often been misrepresented in interpretations of the iconography. There are distinct differences in the context of the presentation of other animals such as otters, fishers, minks or lizards but often these different names have been given by different collectors for the same image.

There are many snake-like creatures found in the mythology of peoples around the Pacific Rim and beyond. These vary in characteristics but are usually associated with a belief in supernatural powers and shamanic practices. They are not seen as “real” animals as they are described in the western scientific tradition.

Information collected by Boas indicated that the Sisiutl or lightning snake might appear in the guise of a fish; shape shifting could bring great wealth – especially to warriors. A Sisiutl could transform itself into a canoe (Boas 1897).

A man speared a “bright salmon” that was actually a “double headed serpent”. The story was given to explain why the double headed serpent was on the front of a house: “a salmon of bright color which they were trying to spear in the river”. It was difficult but the owner of the house succeeded. On this painting the wolf stood on the head of the man in the middle of the double headed serpent (Boas 1921:1117-1119).

In a house of a chief with a double headed serpent across the front he had two large house dishes of double headed serpents obtained in marriage. On the house painting, a Thunderbird sat on the head of the man in the middle of the double headed serpent (Boas 1921:806). A man whose ancestor was a whale obtained through marriage a house with a double headed serpent on the front. Whale was sitting between the eyes of the double headed serpent (Boas 1921:815-816).

The human-like creature seen in the middle of a double headed serpent on soul catchers has not been identified. I propose that it represents Thunderbird man in the middle of two lightning snakes or Sisiutl. His identity can be seen in this rare figure that shows his body with wings (figure 17).

There are changes in how these creatures are portrayed over time in different cultures. For example, the ancient Chinese Fei-yi is presented as a snake with one head and two bodies somewhat like the soul catcher design of the Northwest coast. The Chinese K’uei is a “divine spirit” that is portrayed like a dragon with a plume on the back of its head and a single foot, much like the Haietliks among the Nuu-chan-nulth of Vancouver Island (figure 19). It has the voice of thunder, shines like the sun or moon and brings windstorms. The lung is an early form of the (later) more complex dragon that is portrayed with two or four legs. It also has a plume on the back of its head. These animals were seen as helpers of shamans in communicating between the living and the dead (Chang 1963).

The dragon of Chinese cultures was found in the sky and in the water and had the voice of thunder. Its image was the combination of different animals. It grew to be the symbol of divinity and authority. This was a constant theme of the iconography of China in traditional culture but its artistic forms were different from region to region. Through time the iconography of the dragon appeared on different cultural features with different explanations as to why it occurred there. Locations included the top of bells, the screws of fiddles, stone tablets and monuments, the eaves of temples, sword hilts and prison gates (Williams 1941).

In figure 20 this spindle whorl design is reminiscent of the Ouroboros (in Greek meaning “tail devourer”) of the Old World which shows a snake or dragon-like creature trying to bit or swallow its tail. The creature is perceived as enveloping itself, where the tail representing the past, appears to disappear into an inner domain of reality. This is seen as symbolizing the cyclic nature of the Universe. The ouroboros eats its own tail to sustain its life, in an eternal cycle of renewal.

The great feathered or plumed serpents, Kukulcan of the Maya or Quetzalcoatl of the Aztecs share characteristics with the serpent like supernatural beings of the Northwest coast in their association with shamanism, the earth, sky, lakes, lightning, thunder, wind storms and their physical appearance (Spinden 1975 (1913) ; Freidel, Schele and Parker 1993) .

One of the interesting features of cultures is how iconography changes through time and makes its appearance on different forms of material culture. This is the case on the Northwest Coast where representations of mythical beings may occur on many things or on a limited number objects that may reflect regional differences. It is import to observe what these things are and how the iconography may shift across objects, space and time.

Sisuitls and Haietliks

Among the Kwakwala speaking peoples of Northern Vancouver Island and the adjacent mainland, the Sisiutl is one of the most powerful and important beings in their cosmology. It is often shown as “serpents” with a humanoid face in the center of its body. It is the double-headed serpent used on house fronts and many smaller ceremonial items. Its help was obtained by the ancestors who obtained it as a crest of the clan. The creature had a human head in the middle, knobbed horns, a curled or raised snout, a large mouth and often an extended tongue. This is seen as a creature of transcendence and transformation. It travels through land, sea and sky transforming itself at will. It can take the form of a canoe and leaves behind a trail of slime. It has skin that cannot be pierced. Its glance was believed to kill, or petrify the unwary, who are swallowed whole.

Sisiutl played an important part in the ritual of Winalagis, the war spirit. Any warrior who can acquire the Sisiutl will be given great powers. The blood of the Sisiutl, rubbed on the body of a warrior, makes him invulnerable (Boas 1895:514-515). Stories tell of how the Sisiutl’s scales can be used as arrowheads and his eyeballs used as sling stones can destroy anything. Boas was told that: “The clan Haa’naLino have the tradition that their ancestors used the fabulous double- headed snake for his belt and bow. In their potlatches the chief of the gens appears, therefore, dancing with a belt of this description and with a bow carved in the shape of the double-headed snake” (Boas 1895:358).

Boas was told a story by Neg’e’ of the tradition of clan Ts!o’ts!ena of the A’waiLela of how the Sisuitl has the power to assume the shape of a fish. In the story of The Blind Man who recovered his Eyesight: “Ten Ts!o’na put on his thunder-bird dress, and said, ‘Stay here while I go hunting and looking for fish.’ While he was away, his guests were sitting there. They heard the thunder four times when he was catching his salmon. He carried it home; it was the double-headed serpent. He put it before his guests.” (Boas 1910:44752).

Among the Nuu-chah-nulth of the west coast of Vancouver Island the Haietlik, the mountain or lightning snake, has similar characteristics to the Sisiutl. Its head is sharp and its tongue shoots like lightning bolts. It dwells among the feathers of the Thunderbird. Lightning is caused by the Thunderbird casting down the Haietlik as a harpoon. Thunderbird is a supernatural human being who lives in the mountains. He puts on an outfit of a large bird and puts on his lightning snake belt. Thunderbird shoots bolts of lightning to capture whales – the bolts being lightning snakes. As Sapir notes he wears the haietlik as a belt: “a serpent-like being who causes lightning as he darts through the air or coils around a tree” (Sapir 1919; Sapir and Swadesh 1939; Drucker 1951).

Thunderbirds Harpoon and the Haietlik

The iconography of the Haietlik is seen on the antler or sea mammal bone valves or barbs of some whaling harpoons. In a letter from “Atliyu” of Clayoquot to Charles Newcombe on October 19, 1905, he describes a harpoon he is sending:

“You are getting a relic indeed not one of the common kind but such as carried the charm to win ten whale in one year. These the Indian do not care to sell only you are as a father to me and I want to be a good boy a while I am at it. …The harpoon has a particular name – Too toots yuk soolth – meaning the spear of the Thunder Bird (Atliyu 1905).

Charles Newcombe acquired additional information from Atliyu regarding an example of a harpoon with etched values sent to the St. Louis Exposition of 1904. The Haietlik: “as sketched on harpoon’s barbs. Only used by men who have been successful; on their first hunt and when the whales are inshore. In fine weather, when whales are outside they use the Thunderbird etching”.

Newcombe also received information from Rev. Charles Moser that was provided by Chief Joseph or Wikaninish on the origin of Haietlik: “The Clayoqouts have a tradition that the second ancestral Wikininish was a very successful hunter of whales and that he used to go up a high mountain on the darkest nights to pray for help in his occupation. Once when at the top of the mountain he was inspired by a certain spirit to kill and skin a supernatural being in the form of a snake. When whaling he took with him concealed in a locked box this magic skin and used it as a charm” (Newcombe family papers).

The Movement of Cultural Features

Much of the history of humanity is the history of the blending of cultures. On the Northwest Coast the transformation between humans, other animals and supernatural beings is well ingrained in all cultures. Thunderbird is a transforming being that is linked to the lightning snake almost as a composite entity among the Nuu-chan-nulth and Kwakwala speakers. Some of the Salish language speakers had a long tradition of the Sunulkey or “lake monsters” or giant “supernatural snakes” that had some similar characteristics to the Sisuitl and Haietlik. The Sunulkey lived mostly in lakes and bogs, but could also be inherited as special spirit powers. I see the blending of the Nuu-ch-nulth Thunderbird complex with the pre-existing Sunulkey, supernatural snake of some Salish speakers. The transformers of both cultures transforming to syncretise and consolidate two traditions to suit the changing social relationships.

On the end of one of the Thunderbird whale bone clubs of the Nuu-chan-nulth in the British Museum is a Haietlik design very similar to the designs of some Cowichan spindle whorls (figure 24).

I see the late period introduction of some aspects of the Thunderbird Complex Iconography on spindle whorls, such as the Thunderbird catching a whale, as coming from a late pre-contact or early historic time period from the whale hunting Nuu-chan-nulth of the West Coast of Vancouver Island where the Thunderbird Iconography of the whale hunt is more prominent.

As many recorded oral histories indicate, the diffusion of ritual and associated material objects is part of an ongoing process among cultures of the Northwest Coast. Boundaries are transgressed when the social and environment setting is right for their movement. Secret societies have moved in early historic times from Nuu-chan-nulth cultures into the territory of speakers of languages of the Salish language family. Anthropologist Wayne Suttles best explains the complexity of the diffusion of ritual and material objects in the region:

“The secret society had almost certainly spread from the Makah to the Clallam and on to the Skokomish and from the Nitinat to the Songhees. The sxwayxwey is believed to have spread within the Halkomelem area (though traditions do not agree on the direction) and it seems to have been spreading recently into the

Northern Straits area. The mechanism has been intermarriage and the transfer of ceremonial privileges to sons-in-law and grandchildren. Thus we find not only that the distributions of culture traits or complexes – trait or complex boundaries – do not come in neat bundles that allow us to draw boundaries of societies, but we also find that the trait or complex boundaries can move. It seems likely that ceremonial activities move more readily than some other kinds of culture complexes. But it would be unwise to suppose that any but the most environment-bound are altogether stable. Language boundaries also shifted, probably less often through migration or invasion than through the gradual substitution of one language for another in villages at boundaries.” (Suttles 1987:248).

There is a relationship between people and images. In the absence of writing, communications are expressed not just in oral history, but in all visible forms of iconography from still objects on buildings to moving images on canoes and those used during theatrical performances. There is a reciprocal relationship between oral history providing the context or explanation for the iconography and iconography providing the context for guiding the oral history.

The iconography of the Thunderbird complex serves to visually bring to life the present with the past, to distinguish individuals and families that have a history, that have the rights and special powers to control the resources within their territories.

Imagery on Spindle whorls is part of a socially defined network. They are images of power and connections. We may be enthralled by the aesthetic appeal of the iconography of the Thunderbird complex, but we cannot view the images in the same way as we view “high art” in modern western society.

The mythology – the recorded oral history – is the key to viewing and understanding what the images are and set a framework for potential interpretations of how they relate to the culture of which they are an essential part.

Just as petroglyphs are imprints on a landscape that extends beyond the surface of the rock and involves exchanges between worlds of what we might call dimensions – spaces of being – evidence of connections with other worlds or worlds of the past.

In the modern Western view the expressive medium of an artist tends to illicit a focus on a goal of conveying the individual artist’s values and meanings.

There are at least two people involved in the expression of whorl imagery – the artist who made it and the individual or family that puts it on public view in the context of their history and social relations. When viewing indigenous iconography this broader context needs to be considered.

The message in the imagery of the spindle whorl is: I have the power of the Thunderbird or its associated thunder, lightning snake or whirlwind. The Thunderbird man in his human-bird transformation is the subject of the imagery. The whorl spins like a whirlwind and makes the Thunderbird and lightning snakes fly. What the images do rather than what they mean can only be interpreted in the broader context of the social system of which it is part.

Spindle whorl images have less to do with weaving and more to do with the actions and social context of the weaver and their family. The imagery grows out of specific historical traditions. The thunderbird context can move from one culture to another – such as via female weavers.

The object – The round shape plays a role in dictating the style of the imagery and how it is expressed. Some small whorls appear to have had geometric designs first and then a different kind of supernatural relational iconography late in time after the introduction of large whorls.

Experiences referred to in mythology are often related to interactions with other cultures. Elements would be borrowed or retained if they fitted existing interests and realities or could be modified to suit them. One can have Thunderbird power, without having Thunderbird masks.

Why were whorls and designs on them introduced?

When the small spindle whorls were introduced they were likely an adaptation to a changing world – the need to produce nettle string for a more massive scale fisheries to feed the increasing populations. Later the production of wealth through the weaving of items such as blankets and capes became important and led to the adoption of iconography that expressed that wealth and the social relations of the weavers. Larger whorls appeared to serve the needs of these new elements of production. The archaeological evidence for more intense dog breeding and collection of mountain goat wool and other plant materials will provide a better picture of this in the future. Designs appeared on large spindle whorls only among some of the fifteen populations whose languages are part of the larger Salish language family. In some cases the designs were a product of developing social relations – the blending of peoples with different cultural traditions. Future archaeology may show that designs on small whorls developed late in time after the introduction of larger whorls. Designs on some smaller whorls were early but of geometric styles. Some designs on larger whorls and shapes of whorls are clearly inspired by historic western designs or concepts.

The circular structure of the whorl helps define the likely-hood of interpretive uses. In the design of the Thunderbird in various transformations the hole for the spindle goes through the mouth or the solar-plexus as it does on other cultural devises elsewhere. One could conceive that the spindle transporting through the solar-plexus would be seen like a Worm Hole to an inner dimension connecting people to their ancestors.

Conclusion

People throughout the world have long tried to maintain their identity through belonging to ethnic groups, nationalism, religion, traditional foods or items of material culture and their related behaviors. Just as some of my Scottish ancestors have reconfigured ideas about clan kilts, bagpipes and haggis, so have some indigenous peoples of the Northwest Coast reconfigured the function of the spindle whorl and its iconography as a form of group identity that captures and engulfs a broader audience.

The topic of contemporary use of spindle whorl iconography has been covered by Diane Keighley who was concerned with the social relations that stimulate the recent production and use of spindle whorls and how they reinforce notions of cultural continuity and strengthen the position of central coast Salish peoples within current circumstances (Keighley 2000). In my examination of Indigenous spindle whorls in museums around the world I have chose not to deal with the many modern examples of whorls made as models or works of Art.

My interest is in examining the iconography of older whorls, their regional or time sensitive design topics and how indigenous mythology and other documentation can inform us to gain an understanding of the subject matter, and social relations expressed in these artifacts.

In traditional indigenous societies individuals gained special spiritual powers due to the encounters of their ancestors with supernatural beings. The family prerogatives gained from these encounters provided descendants with a sense of identifying who they were and their role in society. These beliefs and rights moved through and across societies, usually through marriage. The constant blending of cultures is a long standing human trait. The spindle whorl and its iconography is an important cultural devise for creatively going into the future with a sense of identity. Like the maintenance of drumming and language it is a connection with the past that will unite people and continue to express itself into the future.

Many of us, both indigenous and not, who have operated in the cultural spheres of society have played a role as agents of change. The divisions of the past, that we have been aware of for so long, have now come into the forefront of the consciousness of modern Canadian society. Now we are moving from the old idea of indigenous peoples blending into the so called “dominate culture” and are seeing our being in the world together in a collaborative manner. To use a partial phrase from the current pandemic of covid-19, we can now begin to level out the curve of power.

References

Adamson, Thelma. Thunder. 1934. In: Folk Tales of the Coast Salish. Collected and Edited by Thelma Adamson. Memoirs of the American Folklore Society, Vo. XXVII, Published by the American Folk-Lore Society, G.E. Stechert and Co., New York, Pp. 315-324.

Atliyu. 1905. Letter of October 19, 1905 to Charles Newcombe. Newcombe Family Papers. RBCM Archives Add Mss 1077, Vol. 1, file 9.

Barnett, Homer. 1955. The Coast Salish Indians. University of Oregon, Eugene.

Barrett, Samuel. 1915. The Samuel Barrett Collection. Collected in 1915. Information from his field notes. Publications in Primitive Art 2. Milwaukee Museum. 1966. Ed. Robert Ritzenthaler and Lee A. Parsons. Text by Marion Johnson Machan.

Beckham, S.D. 1977. The Indians of Western Oregon. This Land was theirs. Arago Books. Coos Bay Oregon.

Boas, Franz. 1897. The Social Organization and the Secret Societies of the Kwakiutl Indians. British Association for the Advancement of Science Report for the Year 1895:311-738.

Boas, Franz. 1889. British Association for the Advancement of Science. Report for the Year 1886-1889.

Boas, Franz. 1891. Second General Report on the Indian of British Columbia. Report of the sixtieth meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science held at Leeds in September 1890, p. 582-604. London: John Murray.

Boas Franz and George Hunt. 1902. Kwakiutl Texts. Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History, Vol. V. Part I; Anthropology Vol. 4. Jessup North Pacific Expedition.

Boas Franz and George Hunt. 1906. Kwakiutl Texts. Second Series. Vol. X. Part I. Jessup North Pacific Expedition. Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History. Pp. 2-256. G.E. Stechert, New York.

Boas, Franz. 1906. The Tribes of the North Pacific Coast. Annual Archaeological report 1905. Being Part of Appendix to the Report of the Minister of Education Ontario, Toronto, pp. 235-249. L.K. Cameron, King’s Printer.

Boas, Franz. 1916. Tsimshian Mythology. Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, 1909-1910. Government Printing Office, Washington.

Boas, Franz. 1921. Ethnology of the Kwakiutl. Thirty-fifth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology. Part 2. 1913-1914.

Boas, Franz. 1935. Kwakiutl Culture as Reflected in Mythology. American Folklore Society, Memoirs No.28, G.E. Stechert, New York.

Boas, Franz. 1938. Kwakiutl Tales. New Series. Part 1. Translations. Columbia University Contributions to Anthropology. Vol XXVI. AMD Press, New York.

Boas, Franz , 1910. Kwakiutl Tales. Volume II. Columbia University Contributions to Anthropology. Edited by Franz Boas. AMS Press New York.

Bouchard, Randy and Dorothy Kennedy. 2002. (Editors and Annotators).Indian Myths & Legends from the North Pacific Coast of America. A translation of Franz Boas’ 1895 edition of Indianische Sagen von der Nord-Pacifischen Kuste Amerikas.

Chang, Kwang-Chih. 1978. The Archaeology of Ancient China. Third Edition. Revised and Enlarged. Yale University Press. New Haven.

Chen, Maa-ling. The Cultural Construction of Space and Migration in Paiwan, Taiwan. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 29(3):393-406.

Cove, John. 1987. Shattered Images. Dialogues and Meditations on Tsimshian Narratives. Carleton Library Series., Carleton University Press, Ottawa.

Cryer B.M. 1936. Origin of the Thunderbird. The Daily Colonist, Victoria, B.C., Sunday, August 9, 1936.

Deregowski, Jan B. 1972. Pictorial Perception and Culture. Scientific American. 227:5:82-88.

Drucker, Philip. 1951. The Northern and Central Nootkan Tribes. Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology. Bulletin 144. United States Government Printing Office,Washington.

Gell, Alford. 1998. Art and Agency: An Anthropological theory. New York. Clarendon Press.

Harris, Martha Douglas. 1901. Scallighan: Or, The Thunder and Lightning Bird. Indian Legends. Translated by Martha Douglas Harris, Victoria, B.C. (Redone as History and Folklore of the Cowichan Indians. Cover and Illustrations by Margaret C. Maclure. Victoria, B.C.).

Hill, Erica. 2011. Animals as Agents: Hunting Ritual and Relational Ontologies in Prehistoric Alaska and Chuckotka. Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 21(3)405-426.

Hudson, Douglas. 1970. Some Geographical Terms of the Saanich Indians of Southern Vancouver Island, B.C. Unpublished paper. Department of Anthropology, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario.

Hobler, Phillip M. Edited by Roy L. Carlson. Publication Number 30,

Archaeology Press, Simon Fraser University. pp. 165-174.

Hunt, George. 1922. Notes on the Anthropoloogy Collection in the Provincial Museum. George Hunt, September 1922. Documented by Charles Newcombe.

Keddie, Grant. 2018. Spindle Whorls of British Columbia: Part 2. Small Spindle Whorls in the Ethnology Collection of the Royal BC Museum. Royal B.C. Museum web site Staff Profiles.

Keddie, Grant . 2016. Spindle Whorls in British Columbia. Part 1. On-line Royal B.C. Museum web site, Curators Profile, December 6.

Keddie, Grant. 2003. A New Look at Northwest Coast Stone Bowls. In: Archaeology of Coastal British Columbia. Essays in Honour of Professor

Keighley, Diane Elizabeth. 2000. “Almost Lost but not Forgotten”: Contemporary Social Uses of Central Coast Salish Whorls. Master of Arts. Department of Anthropology and Sociology, University of British Columbia.

Kobrinsky, Vernon. 1980:15. Symbolic Immortality. The Tlingit Potlatch of the Nineteenth Century

Kobrinsky, Vernon. 1979. The mouths of earth: The dialectical allegories of the Kwakiutl Indians. Dialectical Anthropology . 4, 163-177.

Lane, Barbara. 1951. The Cowichan Knitting Industry. Anthropology in British Columbia. No. 2:14-27. British Columbia Provincial Museum. Department of Education. Victoria, B.C.

Locher, G.W. 1932. The Serpent in Kwakiutl Religion. A Study in Primitive Culture. Late E.J. Brill Ltd. Publishers and Printers, Leyden.

Losey, Robert J. And Dongya Y. Yang. 2007. Opportunistic Whale Hunting on the Southern Northwest Coast: Ancient DNA, Artifact, and Ethnographic Evidence. American Antiquity. Vol. 72, No. 4.

Machan, Marion Johnson. 1966. Masks of the Northwest Coast, Publications in Primitive Art. Milwaukee Museum. Edited by Robert Ritzenthaler and Lee A. Parsons.

Mathews, J.S. 1955. Conversations with Khahtsahlano. 1932-1954. Compiled by the City Archivist, Vancouver, British Columbia.

Marshall, Daniel. 1999. Those Who Fell From the Sky. A History of the Cowichan People. Cultural & Educational Centre Cowichan Tribes.

Maude, Ralph 1978. (editor). The Salish People. The Local Contribution of Charles Hill-Tout. Volume III: The Mainland Halkomelem. Edited with an Introduction by Ralph Maud. Talon Books, Vancouver.

Newcombe, William A. 1931. Thunderbird and Whale. Report of the Provincial Museum for 1929. King’s Printer, Victoria. P. 10-11.

Newcombe, Charles . Newcombe Family Papers. RBCM Archives. Add Ms 1077.2 Vol. 56, file 2, # 721 &766.

Ravenhill, Alice 1944. A Cornerstone of Canadian Culture. An Outline of the Arts and Crafts of the Indian Tribes of British Columbia. Occasional Papers of the British Columbia Provincial Museum. King’s Printer, Victoria.

Robb, John. 2017. “Art” in Archaeology and Anthropology: An Overview of the Concept. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 27:4:587-597.

Rozen, L. David. 1978. The Ethnozoology of the Cowichan Indian People of British Columbia. Vol. 1. Fish, Beach Foods and Marine Mammals. Unpublished Manuscript.

Rozwadowski, Andrzej 2017. Travelling Through the Rock to the Otherworld: The Shamanic ‘Grammar of Minde’ Within the Rock Art of Siberia.

Sapir, Edward. 1919. A Flood Legend of the Nootka Indians of Vancouver Island. Journal of American Folklore, 32:351-355.

Sapir, Edward and Morris Swadesh (1939). Nootka texts: tales and ethnological narratives, with grammatical notes and lexical material. Philadelphia, Linguistic society of America, University of Pennsylvania.

Suttles, Wayne. 1987. Cultural Diversity within the Coast Salish Continuum. Pp. 243-249. In: Ethnology and Culture. Reginald Auger, Margaret F. Glas, Scott MacEachearn, and Peter H. McCartney (editors), University of Calgary, Alberta.

Swanton, John R. 1909. Tlingit Myths and Texts. Smithsonian Institution. Bureau of American Ethnology. Bulletin 39. Washington Government Printing Office.

Wells, Oliver N. 1970. Myths and Legends. Staw-loh Indians of South Western British Columbia. Compiled by the late Oliver N. Wells. Sardis, B.C.

Abbreviations for Institutions

American Museum of Natural History. AMNH.

British Museum. BM.

Burke Museum. BurM.

Miwaukee Museum. MM.

Rotterdam.

Royal B.C. Museum. RBCM.