By Grant Keddie. May 26, 2023.

This Archaeological site, DcRu-123, is located in the outer portions of Victoria’s Inner Harbour in the traditional territory of the Lək̓ʷəŋən people. It is located on Lime Point – a peninsula that once existed between Lime Bay and Mud Bay to the East of Catherine Street. Part of Lime Bay still exists, but Mud Bay is completely filled in and covered with condominiums. The site was, at least intermittently, occupied from twelve to five hundred years ago (Keddie 1983).

This whole area of eastern Victoria West to the east of Alston Street was an historic Indigenous village and then Reserve of the Songhees from 1844 until they moved to a larger reserve off Esquimalt Harbour in 1911 (Keddie 2003).

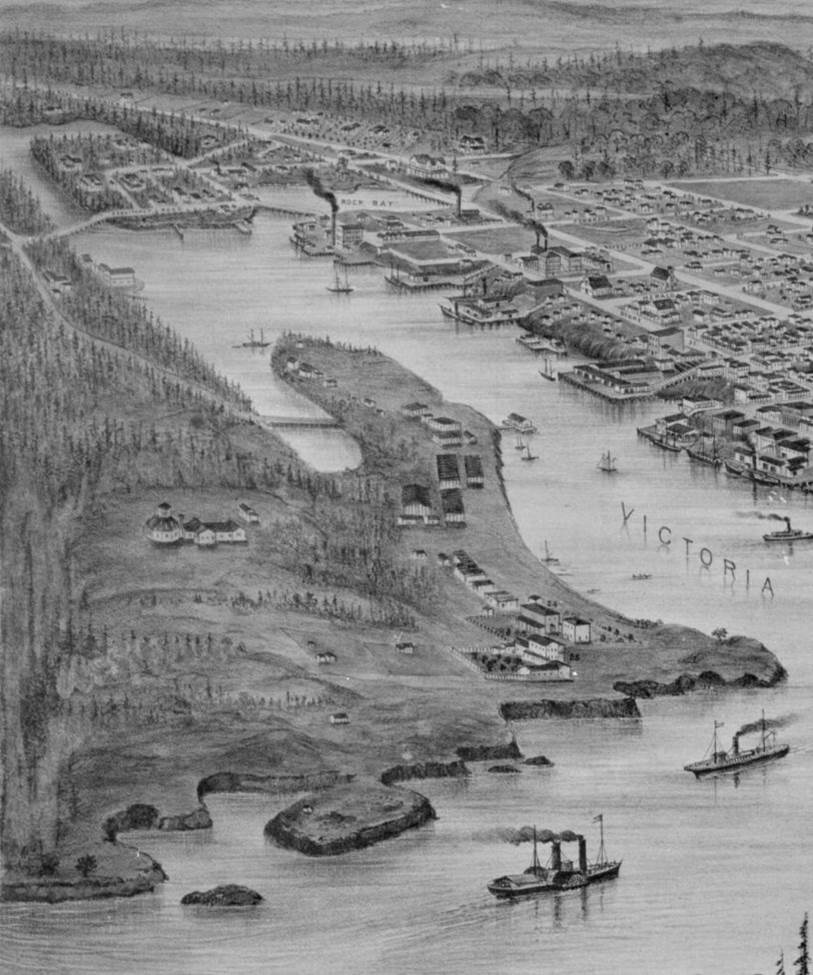

Figure 2 shows Lime Point on a portion of the 1878, Birdseye View of Victoria. It shows the landscape extending east from what is now Mary Street (west of Spinnakers Pub at Lime Bay) to the rocky Songhees Point at the narrows of the Inner harbor. The hill behind the Lime Point became a dumping ground for city street cleaners and then a heliport. It is now a public park and site of high rises.

The Lime Point site is what is called an Indigenous defensive site because it once had a defensive trench dug across the inner narrow part. The trench would have had a wall of posts on the seaward side of the trench to keep out enemies.

Figure 3, shows a portion of the trench which is seen as a foot path at the back of the Lime Point peninsula when this photograph was taken around 1903. The photograph shows Indigenous visitors from the west coast of Vancouver who camped here on a season bases in historic times (Keddie 2003). Figure 4, is a close up of the area shown in figure 3 with the foot path across the trench.

Figure 5, shows, on the right side, a shingle mill with massive layers of sawdust covering the top of the Lime Point peninsula. The Mill building was located on the east side of the Peninsula on the filled in Mud Bay.

The Excavations of the Lime Point Archaeological Site

Most of the upper areas of this site had been destroyed over the years. Although it was recognized by Harlin I. Smith of the National Museum in 1929, passing by in a train, and noted as “The Lime Bay Fort” in 1935, by William Newcombe working for the B.C. Provincial Museum, it was assumed to be destroyed by the 1960s. I suspected that there might be something buried under those piles of shake mill waste and decided to formally record it as an archaeological site in 1976.

I did observe midden in small test holes, which resulted in my excavating some of the last remains of the Lime Point defensive site in 1983 (Permit 1983-9). The remains of parts of the site were preserved by being buried under tons of sawdust. The Archaeological site was composed of an accumulation of charcoal-stained soil from fires, broken rocks once used as cooking stones and shells and bones discarded from thousands of dinners. Figure 6, shows Archaeological excavation pits extending from the 1983 surface down to bedrock. The exposed bedrock is a part of the site that was dynamited away. Figure 7, shows the location of the excavation pits just above where my VW Van is parked. The old Mud Bay is filled in and asphalted over. This Bay began to be filled in with City garbage by the late 1930s. Kimta road extends along the back of the bay.

During the preparation of the peninsula location for a City Park in 1987, the disturbed areas near the exposed bedrock surfaces were power washed. During this procedure I observed undisturbed shellmidden features in one of the deeper crevices in the bedrock (figure 9 and 10). Scattered around the area were numerous small round rocks of a uniform size which I surmised must be sling stones used for defensive purposes (figure 8). These stones were not found in any of the local beaches. I was able to extract a good charcoal sample from these deposits that would represent an early occupation on the site. Figure 8, shows a sample of the large number on small round sling stones laying just above the bedrock.

Faunal Remains and Artifacts

Food remains from the site showed that the First Nations who lived here consumed a lot of native oyster, native littleneck and butter clams, as well as bay mussels, crabs, barnacles and whelks. Horse clams and basket cockles were present but rare. The larger clams were not found on local beaches and must have been brought to the site from another location. We found thick concentrations of sea urchin remains and numerous clusters of scales and bones of anchovies and herring fish. The large runs of anchovy no longer come into Victoria Harbour due to over-fishing in the 19th and early 20th century.

Other food remains included Coho salmon, species of rockfish, flatfish and ratfish, several species of ducks and the great blue heron. Small quantities of mammal bone were mostly deer, with a few elk, porpoise and raccoon.

Few artifacts were found at the site. Those recovered include a knife made of the large California mussel shell, various bone tools, antler wedges used mainly in woodworking and a sandstone abrader used to grind bone and shell tools.

Dating the Site

I have received two radio-carbon dates on this site. During the formal excavations in 1983, I received a basal date on charcoal of 540 +_ 80 B.P. (SFU 383). This gives a time range from 1330 A.D. to 1490 A.D. for this part of the site. After this project when the ground surface was being stripped down to bedrock, on what would have been the S.W. corner of this site, I extracted a charcoal sample for dating from the base of these deposits. The new date came back as 1240+_80 (SFU791). The date (calibrated age of 1173 BP or 777A.D.) must represent an early, if not the earliest, occupation of the site given that it was in a deep crevice right above bedrock. We can now estimate that DcRu-123 was occupied at least intermittently from about 1200 to 500 years ago.

Because of the missing or seriously disturbed upper deposits of the site we cannot provide a solid date for site abandonment. However, there was no Indigenous knowledge or tradition about this site and it was not occupied when the first Europeans came into Victoria Harbour in the mid-1800s. This suggests that it was not likely to have been occupied in the last 300 years.

This site was likely occupied mainly on a season basis for acquiring the herring and anchovy runs and oysters found in the Gorge waterway. It is one of a number of defensive locations around Victoria (Keddie 1996;1997). It is one of only three pre-contact sites in Victoria’s Inner harbour – which extends eastward from a line across the Harbour to Shoal Point. The other two sites include the Capital Iron site DcRu116 (Keddie 2018) which is around 400 years older and the undated archaeological site on Raymur Point that is right across the harbour from Lime Point and is also located on a raised peninsula (Keddie 2017).

The Historic Burial Site

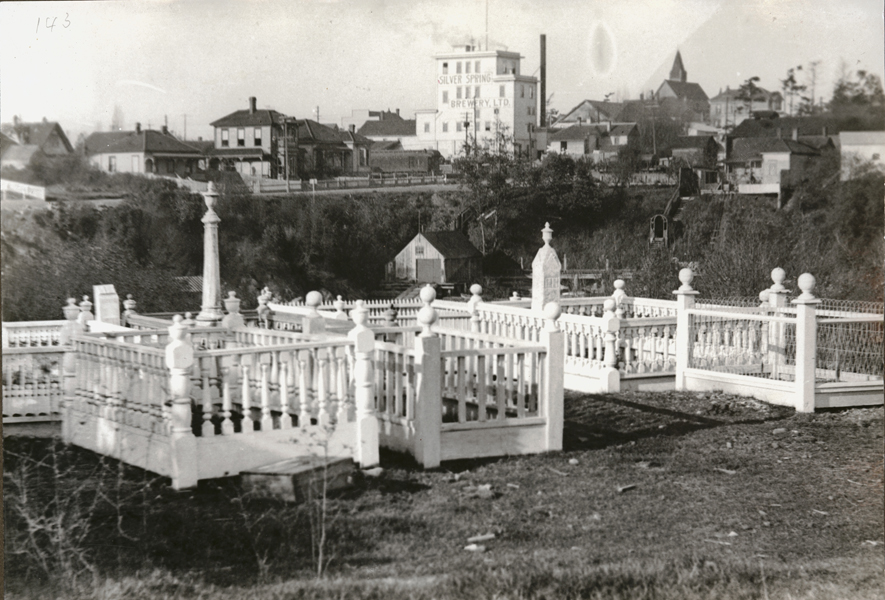

In historic times the peninsula was on the Old Songhees reserve and used as a Christian burial ground. There were no burials in the older pre-contact deposits.When the Old Songhees Reserve was moved in 1911, arrangements were undertaken to move the Indigenous burials to a new location on the Songhees reserve. Some, however, were unmarked, buried deeper than the others and were missed. These were uncovered during various construction projects and eventually returned to the new Songhees cemetery. The old cemetery can be seen in figure 12, with houses on Catherine Street above the steeper northern portion of Lime Bay. The Silver Springs brewery can be seen on the Northwest Corner of Esquimalt and Catherine Streets.

The Lime Point Site Today

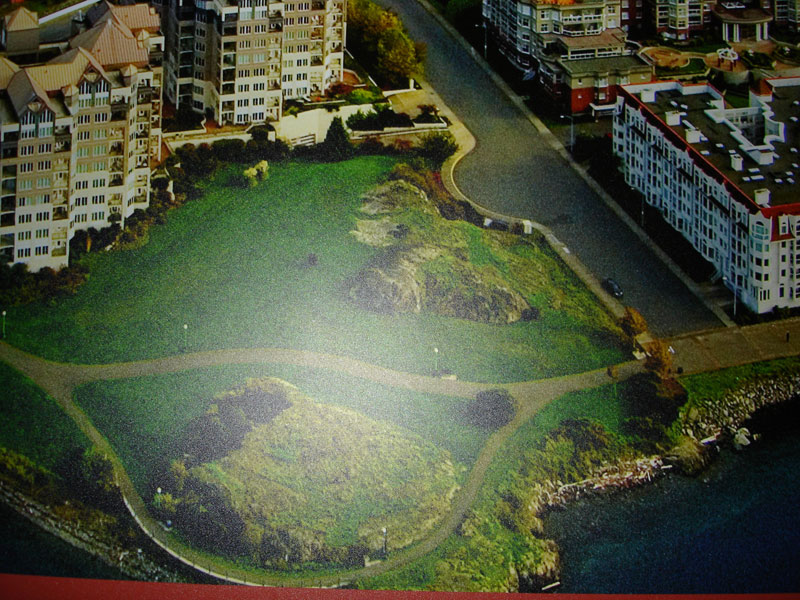

Today, along the waterfront to the east of Lime Bay, one can still see a rock mound with a light scattering of shellmidden – all that is visible of the old Lime Point peninsula village. Although there will be pockets of midden buried below. Figure 13, shows part of the filled in portion of Lime Bay on the left, now joined to the old Lime Point Peninsula. The original Lime Bay went north past what is now Kimta Road. Figure 14, shows the rocky remnants of Lime Point from the East. The road in the foreground (Cooperage Place) was part of the old Mud Bay.

Figure 15 shows the eastern portions of the site from above. Figure 16 shows the site from the water and figure 17 shows the whole site from above.

References

Keddie, Grant. 2018. The Capital Iron Site, DcRu-16. Victoria Harbour. On-line Royal B.C. Museum web site, Research. January 25. (And web site grankeddie.com).

Keddie, Grant. 2017. A First Nations Shell Midden on Raymur Point, Victoria Harbour. On-line Royal B.C, Museum web site, Curators Profile, Research. September 11. (And web site grankeddie.com).

Keddie, Grant. 2003. Songhees Pictorial. A History of the Songhees People as seen by Outsiders, 1790-1912, Royal B.C. Museum, Victoria.

Keddie, Grant. 1997. Aboriginal Defensive Sites. Part 4: Local Sites are Dated; Final Conclusions. Discovery. Royal B.C. Museum News and Events, 25 (2):5. (And web site grankeddie.com).

Keddie, Grant. 1997. Aboriginal Defensive Sites. Part 3: Modern Archaeologists Collect Evidence. Discovery. Royal B.C. Museum News and Events, 25 (1):4-5. (And web site grankeddie.com).

Keddie, Grant. 1997. Aboriginal Defensive Sites. Part 2: Amateur Archaeology Begins. Discovery. Royal B.C. Museum News and Events, 24 (9):5. (And web site grankeddie.com).

Keddie, Grant. 1996. Aboriginal Defensive Sites. Part 1: Settlements for Unsettling Times. Discovery. Royal B.C. Museum News and Events, 24 (8):7-8. (And web site grankeddie.com).

Keddie, Grant. 1983. The Victoria Songhees Development Area Survey and the Excavation of the Lime Bay Fortification Site, DcRu l23. A Report to the Heritage Conservation Branch of the Ministry of the Provincial Secretary and Government Services pertaining to Permit No. l983‑9.