By Grant Keddie

Aboriginal peoples, from the central coast of British Columbia to SW Alaska, represent the octopus in their art, myths and ceremonies. All First Nations peoples living along the coast also ate octopuses, which are high in protein. But while there are many historical accounts of skinned octopus arms being used to bait hooks for halibut fishing, there are few descriptions that have been uncovered about where and how octopuses were caught.

Some accounts have been found for the south end of Vancouver Island. In 1951, James Fraser of the Songhees told anthropologist Wilson Duff that the “big rock” in Gonzales Bay was called “devilfish rock” and “If you touch that rock, devilfish come up.” It was also known as a location “where devilfish spawn.”

There are also two early references to hunting octopuses in Esquimalt Harbour. One passage from the 1860s refers to an observation by Eleanor Smyth who lived above the bay east of the steep peninsula at the foot of Stewart Road, from 1861 to 1866:

“One day she saw our Indian handyman in his canoe pushing his spear into the rocks just below the sea level and close to where we lived. Presently he landed his catch, a large octopus, now lifeless, into his canoe, and then took it home to his village opposite.”

Around the same time, in the early 1860s, the British naturalist John Lord was in Esquimalt Harbour and described a hunt:

“The Indians were going after the Octopus, and I felt a strong curiosity to see how they caught him …The Octopus of our own seas is a mere dwarf as compared to the gigantic size he obtains in the land-locked harbours so common to the east side of Vancouver Island. … [Aboriginal Peoples regard] Octopus as we do turtle, and devours him with as much gusto and relish, … roasts his glutinous carcass instead of boiling [it]. The Indian well knows . that were the Octopus to get his huge arms over the side of the canoe, and at the same time a hold-fast on the wrack, he could .easily upset the canoe, .[so] paddling the canoe slowly and quietly amongst the wrack, he steadily looks through the crystal water until his practiced eye detects the Octopus, his great arms stiffened out, patiently biding his prey. Armed with a formidable spear carefully barbed, and about twelve feet in length, …[the hunter] passes it carefully through the water until within an inch or so of his great pear-shaped centre, then sends it in as deep as he can plunge it. Twisting and writhing .. the monster coils his terrible arms round the spear; . [then the hunter,] resting his spear on the side of the canoe, keeps him well away and raises him to

the surface of the water. He must be dealt warily. .[Knowing this, the hunter] has ready another spear, long, smooth, unbarbed, and very sharp, and with this stabs the Octopus where the arms join the body. I imagine the spear must break down the nervous centres giving motive power, for the stabbed arm is at once deprived of its strength and tenacity.”

In the 1930s and 1940s, anthropologists recorded local aboriginal elders saying octopuses were boiled as well as roasted, that some octopuses were captured with a spear having two fixed, barbed points and that they were mainly hunted from a canoe in about one to three m (3 to 10 ft) of water at low tide.

Another record suggests that an adaptation of the European method of poisoning the water with copper sulphate may have been added to the traditional octopus-hunting practices of a Klallam group that was located 35 km (22 mi) from Esquimalt Harbour on the south side of the Strait of Juan de Fuca:

“Bait for halibut fishing was fresh devil-fish. These are caught near Pysht where their rocky lairs were made accessible at low tide. A stick is used as a probe which [is] thrust into the recesses where the octopuses are thought to be. Usually the sand and gravel around the opening was brushed clean and scattered with small shells which were residue from the octopus’ feeding. If the probe struck something soft it was the body of the octopus. Subsequently, a bag …was filled with blue stone (copper sulphate) and introduced in the hole again. This quickly disintegrated and filled the water surrounding the octopus with a solution that irritated it, causing it to emerge from its lair. Immediately it was seized by the hunter, one hand grasping a leg near the body, the other the body so that the beak might be warded off. As soon as the devil-fish was taken its body was torn apart to kill it and release the ink. The remains were washed, then taken to a sandy part of the beach and rolled to remove the slime. After skinning and dismembering the parts were washed again until the flesh was white.

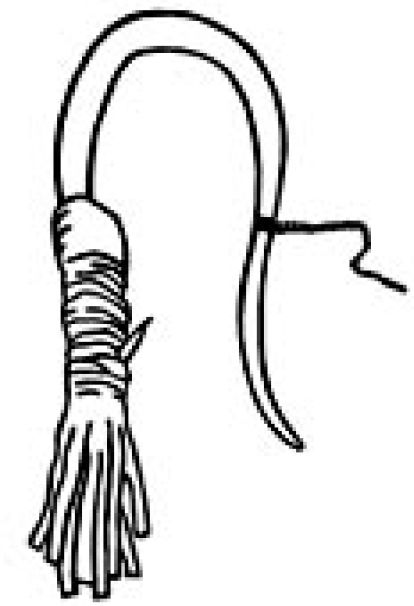

“The tentacles [arms] were chosen for bait and prepared by splitting lengthwise, tearing out the central nerve; then cut into lengths of about 3 to 4 inches [7.5 to 10 cm]. Each small section was fringed at one end. .^Baiting a hook was accomplished by wrapping the piece of flesh around the lower end and over the barb so that it was concealed. The fringe was allowed to play out from the hook resembling a baby octopus. The bait roll was secured by several rounds of white string tied with half-hitch knots.”

An account by ethnologist Phillip Drucker also describes how the northern Nuu-chah-nulth hunted octopuses for use as bait during the halibut fishing season:

“The fisherman searched along rocky stretches of the shore which were exposed at low tide, looking for cracks and caves in which devilfish might be hiding. He had two long, sharpened poles, one with a backward projecting barb. He poked about under the rocks until he felt a devil-fish, then stabbed it with the barbed pole. Then he inserted the other pole, stabbing at the creature, whose movements were indicated by the first rod. Sometimes it was possible to kill the devil-fish in its den and drag it out; more often it was worried until it emerged of itself, when it was killed by biting it on the head. The animal could not be pulled out while it lived. When he killed it, the fisherman tied the devil-fish on a withe and carried or dragged it home. There he skinned the tentacles and hung it outside the house on the wall. The meat would keep for several days this way… To bait the hook, a piece of devil-fish tentacle was split lengthwise and carefully tied over the back of the shank of the hook from the leader to the end of the barbed arm. Some men preferred to put it over the hook from the inside, covering the tip to the barb with a separate piece.”

Among the stories about octopuses, there is an interesting one that shows that they also were able to recognize a good protein source. The Victoria Daily Colonist of December 24, 1888, reports in “In the Grasp of a Devil Fish” that the body of T. J. Hughes, who had “evidently drown,” was found floating in Puget Sound “clasped in the embrace of a huge octopus.”

Bibliography

Drucker, Philip. 1951. The Northern and Central Nootkan Tribes.

Bulletin 144, pp. 480. Washington: Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology. (ref. pp. 43-44)

Duff, Wilson. 1951. Field Note Book #11. (on microfilm, BC Archives) Jenness, Diamond. c. 1938. The Saanich Indians of Vancouver Island. Manuscript 1103-6. New York: American Museum of Natural History. (ref.p. 65)

Lord, John Keats. 1866. Gossip About Man-Suckers. Hardwicke’s Science Gossip:An Illustrated Medium of Interchange and Gossip for Students and Lovers of Nature, ed. Robert Hardwicke. London.

Lugrin, N. de Bertrand. 1928. The Pioneer Women of Vancouver Island, 1843-1866, ed. John Hosie. Victoria: The Women’s Canadian Club of Victoria.

Suttles, Wayne. 1974. The Economic Life of the Coast Salish of Haro and Rosario Straits. Coast Salish and Western Washington Indians 1. New York: Garland Publishing Inc. (refs. pp. 116 and 132)

Washington Archaeological Society (author unknown). 1961.

Washington Archaeologist. Vol. 5, no.10. Seattle: Washington Archaeological Society, Washington State Museum.