By Grant Keddie. Nov 2016.

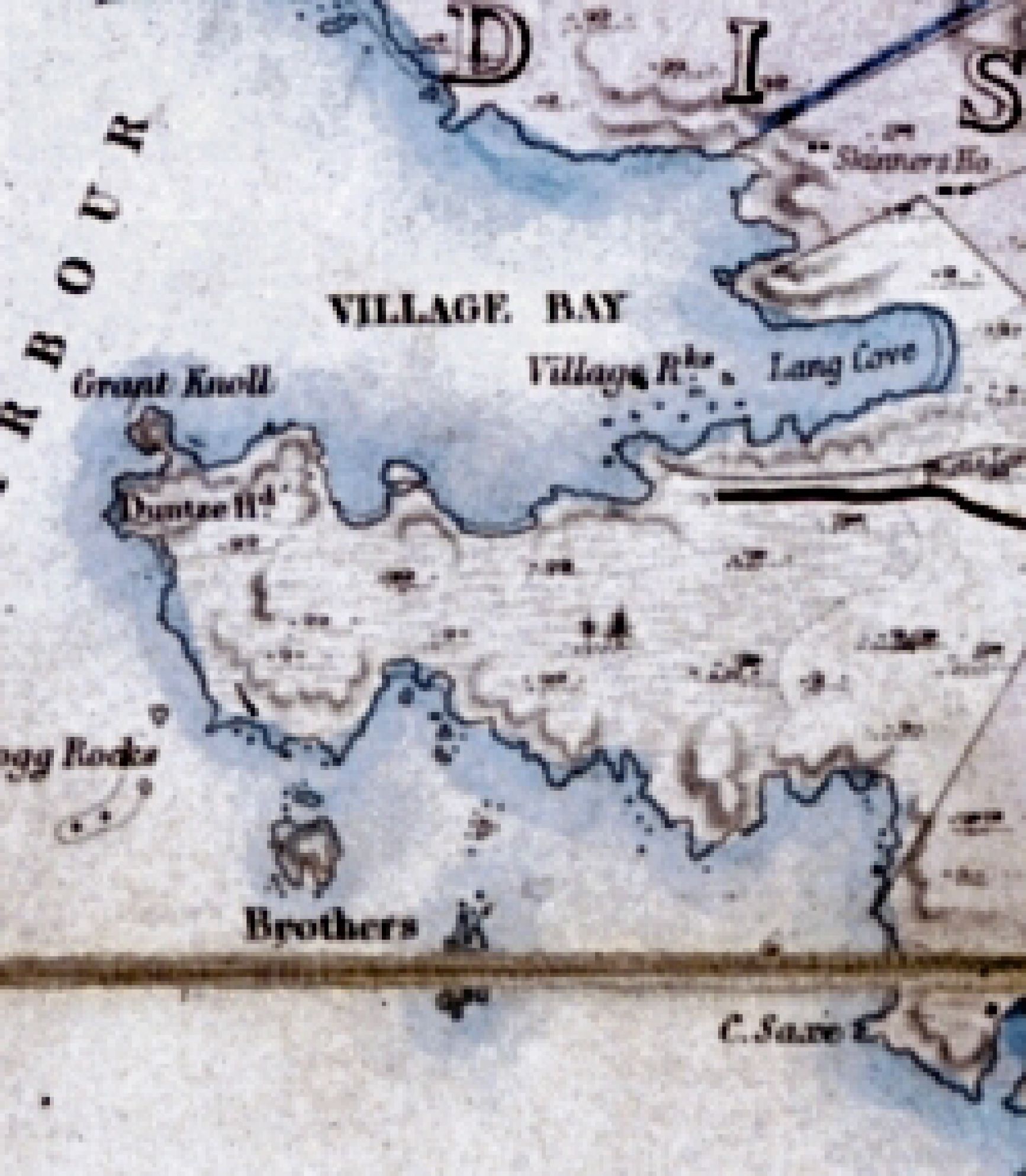

19th century photographic images in the Victoria region that show Lekwungen (Esquimalt and Songhees First Nations) undertaking traditional food gathering practices are rare. The only example of fishing is a photograph, taken in 1868, by Frederick Dally in Esquimalt harbour at the south entrance to Lang Cove (RBCM PN905). Lang Cove is located south of Skinner’s Cove, both of which are within the larger Constance Cove. This is the location of an ancient shellmidden as demonstrated by the scattered white clam shells seen in the image and later observed by the author at this location.

This image (fig. 1 and close-up fig.2) of a man and woman at a herring fishing site is listed in Frederick Dally’s Miscellaneous Papers, (File 17), as #5 “Indian at Esquimalt, canoes, fish etc.”. A copy of the photograph in the RBCM Archives Dally Album #5 has information along the bottom of the image noting what is in the photograph “herrings drying – rush mat- fish spears – Indian woman cooking – Chinook canoes – Esquimalt Harbour V. Island”.

A copy of this photograph was also in the original photo album of Lieutenant J.C. Eastcott, the surgeon on the ship H.M.S. Reindeer that was on duty at the Esquimalt Royal Naval Dockyard station from 1868-75 (now the Canadian Forces Base Esquimalt).

Dating and Location of the Photograph

The album, in the possession of A.R. Eastcott, was temporarily loaned to the City of Vancouver Archives in 1958 where the information written on it was recorded by archivist Major James Mattews. This album was also loaned to the Provincial Archives in 1978, and the information copied down by Dan Savard of the RBCM ethnology division on November 23, 1978. They recorded the caption on this image as “Woods Landing, Constance Cove, Esquimalt 1868”. The reference to “Woods Landing” likely refers to the place that Sir Charles Wood, the First Lord of the Admiralty came ashore in 1856. It could also refer to a landing place used by Lieutenant James Wood who surveyed Esquimalt Harbour in 1846 under the supervision of Captain Henry Kellet, but James Wood’s name was not officially given to this location.

Dates placed on photographs long after the image was taken, and by someone other than the photographer, are often subject to error. In this case the date of 1868, is likely correct, and it would have been taken in late February to April of that year during the herring runs. Dally was away from Victoria in the Interior from June of that year and did not return to Victoria until to February 25, 1869.

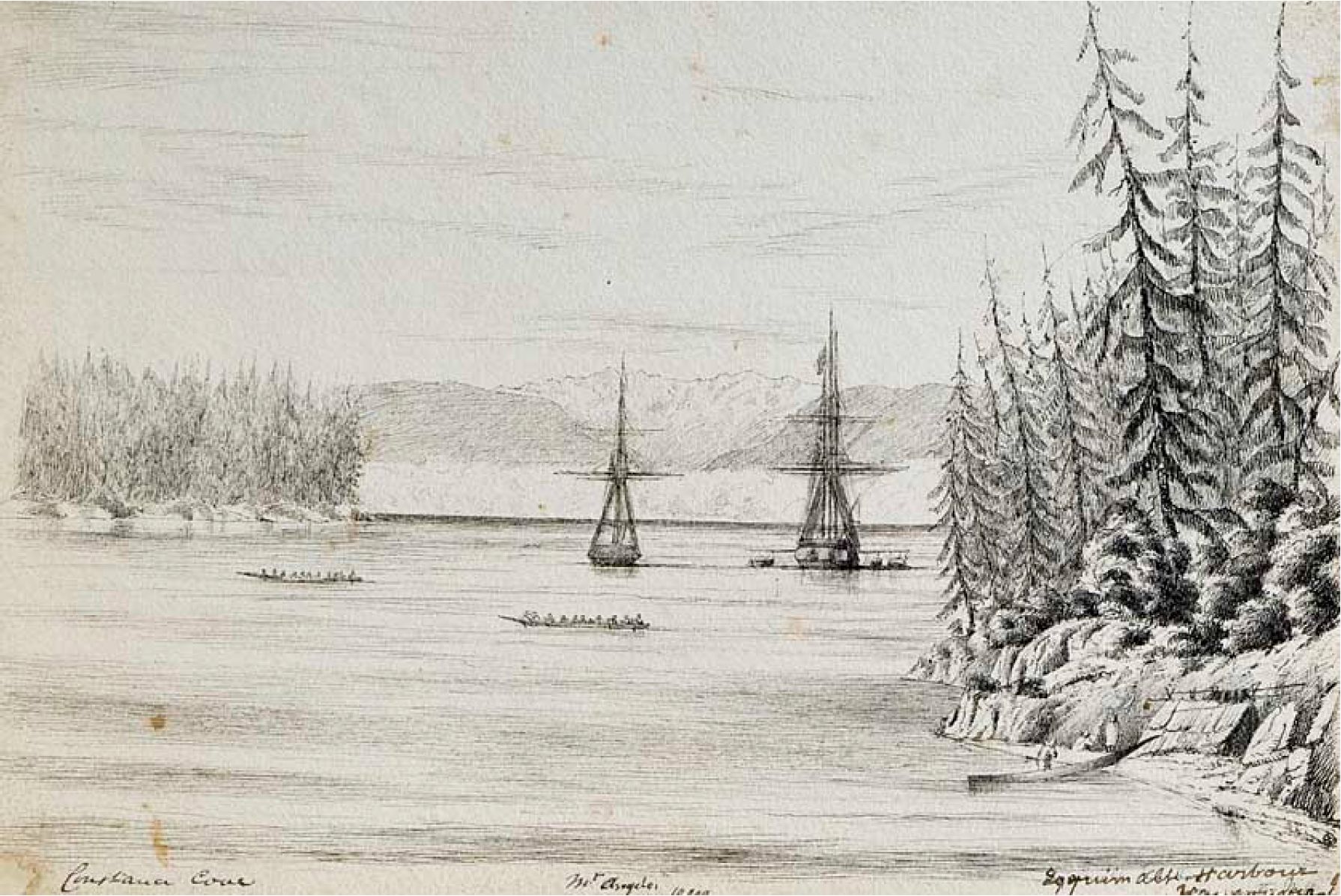

I was able to identify the location where this photograph was taken by observing the same fishing site location in another photograph of Dally’s (RBCM F-08522), that was undated, but one that must have been taken in 1867 (figure 3). There are five ships in this image. The times they were on duty at the Esquimalt naval station allows us to be specific about the time the image was taken. The ships include the Egmont, Sparrowhawk, Alexandra, Malacca, Shearwater and Grappler. As the Shearwater was only on duty in 1867 the photo must date to that year. The vegetation in this image shows similar growth to that in photograph PN905, suggesting the time separation of a year or less is most probable.

In figure 4, the remnants of many fish drying racks can be seen. Note the large number of upright short posts to the left of the photo and the large framework poles just to the right of centre of the photo at the edge of the bank. The fence-like rails in the background are related to Wood’s Landing and the historic naval wooden buildings to the far left of the photo.

Wooden planks that are held by pegs can be seen at the centre. The planks hold back the midden and create a flat platform for a mat lodge location. Barrels can be seen on both sides of this platform. The large pole framework can be seen in the middle against the back in the same location in image PN905 to the right of the tuli mat shelter.

Note the tiny little Island just on the other side of this point. This is part of what was called “Village Rocks” – as seen in figures 5 and 6.

By knowing what naval construction features were in the adjacent areas and by observing the angle of the two above images and what is in their background, the location can be identified as a small hooked piece of land extending into Lang Cove at its southern entrance.

Image PN905 is looking north-east to the North entrance to Lang Cove. Figure 3 (RBCM F-08522) is looking north, with the Officers Club House on Munroe Head visible on the far right and Ashe Head beyond it. Another image, RBCM F-08538, taken in 1866-67 (based on dates of the presence of the boats) and from higher up shows more of the Bay between Munroe Head and Ashe Head.

The small rock Islet (part of “Village rocks”) off the herring fishing site seen in Figure 3 (RBCM F-08522) can be seen on the far left in RBCM Archives image E-01844 – which also shows the rock formation on the north side of the entrance to Lang Cove as seen in the herring fishing camp image.

Adjacent to Wood’s Landing (on the west side of the hooked piece of land in photograph PN905) is a group of rocks in the harbour called “Village Rocks”. This hooked piece of land with the small bay of the campsite photograph can be seen in the detailed map of Esquimalt Harbour produced by Captain Richards in 1859 (see close-up figure 5). Over the years this area has been drastically altered and is no longer visible. The fact that it was named village Rocks suggests that the survey crew mapping Esquimalt harbour may have observe a group of First Nations camped there – even if it was just a seasonal camp site at the time and not what might be called a more permanent winter village site.

The Origin of the name “Village Bay” and “Village Rocks”

The names of some of the bays and coves changed over time. Several maps produced from 1851 to 1855 show “Village Bay” in Lang Cove or where later maps show Constance Cove.

Photograph PN905 shows herring fish on wooden drying racks to the left side of the image. A First Nations man, in European style clothes, is standing in front of a tuli (bulrush) mat summer lodge which is located on a built-in flat platform area faced with a board in front. This is the left of the two board faced platforms that can be seen in photograph F-08522. This is an interesting example of the human modification of a shellmidden.

Note the pathway near the right centre that can be seen in both photos. On the right of the mat lodge are poles for fish drying racks. Some of the long ones may be herring rakes (see figures 1 & 2), but the image is not clear enough to identify these. If Dally observed these, his reference to “spears” in his photograph description may have resulted from him seeing the long herring rakes at the site?

Of the three canoes seen in figure 1, the closest one is of a west coast Vancouver Island style, while the outer two canoes with the long pointed bows and sterns are made of the style most common among Salish speaking peoples of the southern Coast of B.C. and northern Washington State. The term “Chinook canoe” used in one caption is now referred to as the “West Coast” style.

The Rediscovery of the Shellmidden

In the 1980s, Ernie Colwood of CFB Esquimalt took me to the Wood’s Landing location during construction activities. Here I observed tons of historic debri from previous projects on top of and mixed in with shellmidden.

A Second herring fishing site in Lang Cove

In 1851, naval surgeon John Palmer Linton, while visiting on board the HMS Portland, drew a view from the back of Lang Cove (Driver 2013; Driver and Jones 2009). In this image (Figure 12) we can observe, on the far right, a tuli mat shelter with fish drying racks like that in figure 1. This fits the general descriptions of the time about temporary shelters around the edges of Esquimalt Harbour, but no specific mention of this location is in Linton’s writings. We cannot be certain that this imagery was not simply added to enhance the drawing as was a common practice at the time. The added-in drawing of First Nations in canoes near European ships was a common practice among artists.

Herring and Anchovy Fishing 1843-1878

In the 19th century, there were both spring and fall runs of herring and anchovy in the Gorge waterway and Esquimalt Harbour. Anchovy bones are common in archaeological sites but overfishing caused their extirpation from this region around the First World War.

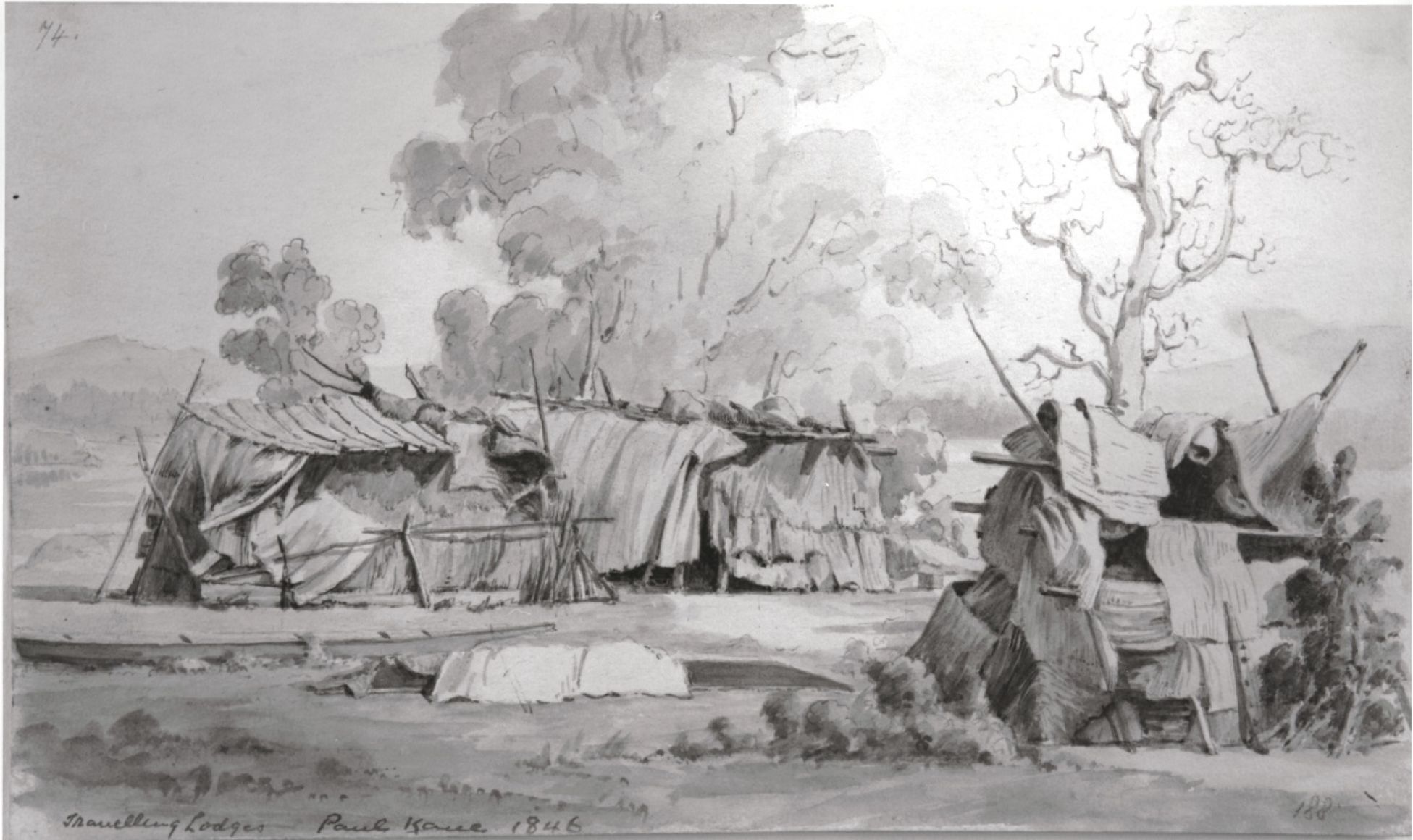

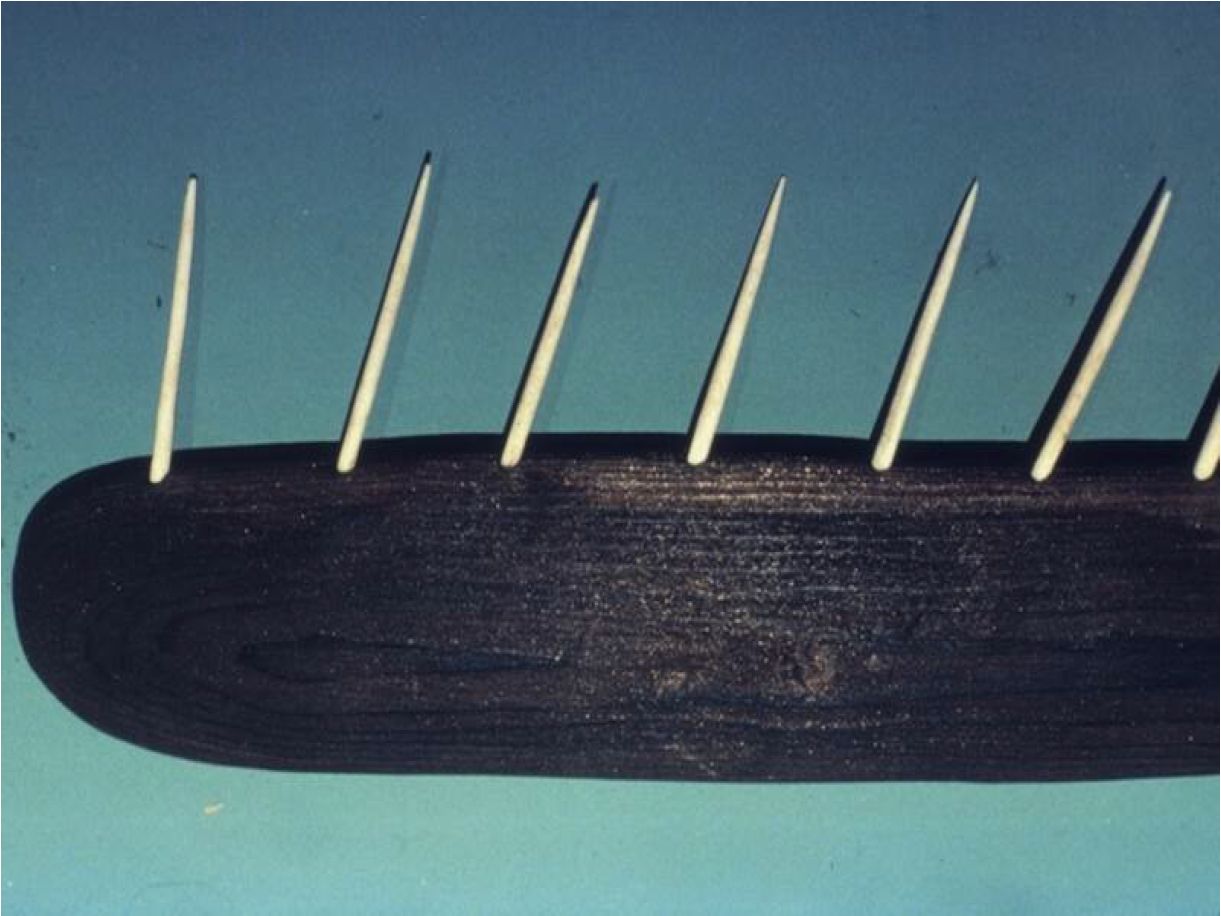

In 1865, Frederick Dally described the spring herring fishery in Esquimalt Harbour. During the fishing season: “lodges spring up like mushrooms along the edges of the bays and harbours …When thoroughly dried the fish are packed in bales made of rush mats, each bale weighing about fifty pounds, the bales being tightly lashed with bark-ropes” and carried by horses back to the “winter quarters”. Some of the fish were used “as lamps forlighting their lodges”. The 6 to 8-foot herring rakes had barbs “usually” of bone but “preferably” of nails. They sometimes catch two to three herring on each tooth. (Dally 1865).

The first written observation of the Pacific herring in this region was by James Douglas in 1843. He notes that they arrive in April and are “taken in great abundance” in Victoria harbour. In April of 1847, the visiting artist Paul Kane observed:

“The Indians are extremely fond of herring-roe, …Cedar branches are sunk to the bottom of the river in shallow places by placing upon them a few heavy stones, taking care not to cover the green foliage, as the fish prefer spawning on everything green. The branches are all covered by the next morning with the spawn, which is washed off into their waterproof baskets, to the bottom of which it sinks; it is then squeezed by the hand into small balls and dried, and is very palatable.” (Kane 1925:148). A similar description is given by Bayley in 1878. He notes the “immense amount” of herring eggs preserved for winter use. The spawn is deposited on Cedar boughs placed “at low water”, then gathered and taken to camp and “stripped after being dried and put into boxes”.

In 1848, James Wood notes that the most common fish taken in the general area of the Strait of Juan de Fuca were “halibut, flounders, skate, rockcod, sardine [anchovy], salmon, trout, and several varieties of the herring.” Sole and flounder were plentiful in the Royal Roads area off Esquimalt Lagoon where the Songhees “would expose flounders on spits to the sun in order to roast them.” Halibut were once very plentiful on the shallow offshore banks from Victoria harbour to Discovery Island.

The Lekwungen increasingly began gathering resources for others. James Bell described the situation in 1858:

“we are indebted to the Indians for a supply of everything in season .at very reasonable rates; They collect great quantities of Berries,.For a back load of Potatoes they charge one shilling; these they cultivate by simply burying the seed under the green turf; A fine salmon can also be purchased for one shilling; .Cod, Herrings, Flounders &c are always to be had cheap; A large Basket of Oysters one shilling; The market is also supplied with plenty of venison, Deer are quite plentiful, until the arrival of the American Hunters”.

A second seasonal herring run was observed by Captain Wilson in 1858-1859. He noted that during October, and November, “herrings and a species of anchovy appear in great numbers”. In 1867, Edward Bogg describes the fishing technique with the “Herrings and whiting [anchovy]”. A pole (14′ X 3″ X 3/4″) has one edge with “very sharp spikes, made of hard wood, and about two inches long”. The fisherman paddles quickly into a shoal of fish “drops his paddle, picks up his rake”, and “makes a sweep through the shoal” impaling 5 or 6 fish which are dropped into the canoe “by striking the rake forcibly on the gunwale”.

Rev. Owens, after mentioning on September 30, 1869 that the Reserve had been nearly deserted over the past three months, due to the Songhees being away fishing, noted: “The abundance of salmon & anchovies (the latter generally but incorrectly named Sardines) has been extraordinary & unless actually seen would appear incredible”.

The B.C. Guide for 1877-78 says that during the autumn the anchovy “abounds in the harbours and inlets” and is easily taken. Recent studies indicate that the Anchovy may have only been in this area for the last two thousand years. Deep sea drilling in Saanich inlet revealed yearly layers with herring remains over the last 10,000 years, but anchovies only appear in the last 2000 years. Weather this is a pattern that pertains to the larger region, will require further research.

Paul Kane, in 1847, observed many of the temporary tuli mat shelters seen if figure 8. He referred to this image as “Clallum travelling lodges”. Although there were Klallam people from the Port Angeles area visiting the Victoria region during Kane’s stay, he sometimes referred to the local Songhees people in the new village across from Fort Victoria as “Clallum”. Kane may have drawn these tuli reed shelters in Esquimalt harbour, but we cannot be certain if he drew this image at that time of his stay here or later during his stay in what became Washington State. Kane noted in his Landscape log # 74, that “These are only used when they go fishing for a short time” (Harper 1971:314; also see Lister 2010:284-285).It is unfortunate that both Harper (1971) and Lister (2010) miss-identify images of the Village on the Old Songhees Reserve in Victoria Harbour as being in Esquimalt harbour. This was a result of Kane ans others referring to the Victoria West area of Victoria’s inner harbour as being “on the Esquimalt” which was in reference to the Esquimalt Peninsula and not Esquimalt harbour.

References

Bayley, Charles 1878. Early Life on Vancouver Island. Manuscript prepared for H.H. Bancroft, pp. 28-31. BCARS, E/B/B34.2.

Ireland, Willard (ed). 1948. A Letter from James Bell. In: British Columbia Historical Quarterly, Vol. XII, No.3, July.

Bogg, Edward B. The Fishing Indians of Vancouver’s Island. Memoirs of the Anthropological Society of London, Vol. 3, 18678-9, pp. 260-265. Paper Read April 30, 1867.

Dally, Frederick. 1865.BCARS, Add. Mss.2443. Misc paper, Box 1, File 14, E/B/D16m.

Douglas, James. 1843. Diary of a Trip to Victoria, March 1 – 2, 1843. RBCM Archives, Ms A/B/40/D75.4.

Driver, Felix 2013, ‘Hidden histories made visible? Reflections on a geographical exhibition’, Transactions, Institute of British Geographers 38: 420-435.

Driver, Felix and Lowri Jones. 2009. Hidden Histories of Exploration: Researching Geographical Collections, Royal Holloway, University of London, and Royal Geographical Society (with IBG), London.

Elliott, Henry W. 1886. An Artic Province. Alaska and the Seal Islands. London. Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Riverington.

Harper, J. Russell. 1971. Paul Kane’s Frontier. Including Wanderings of an Artist among the Indians of North America by Paul Kane. Edited with a Bibliographical Introduction and a Catalogue Raisonne by J. Russel Harper. Published for the Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, and the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, by the University of Toronto Press, Toronto.

Kane, Paul 1925. Wanderings of An Artist Amoung the Indians of North America. From Canada to Vancouver’s Island and Oregon Throught the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Territory and Back Again. The Radisson society of Canada Limited.

Lewis, Adolphus Lee. 1842. Ground Plan of Portion of Vancouvers Island Selected For New Establishment. Taken by James Douglas Esqr. Drawn by A. Lee Lewes L.S. Hudson’s Bay Company archives, Provincial Archives of Manitoba G.2/25 (8359).

Lister, Kenneth R. 2010. Paul Kane/The Artist/Wilderness to Studio. Royal Ontario Press.

Owen, H. B. 1868-69. Reports of Rev. H. B. Owen, Missionary at the Indian Reserve, Victoria, to the United Society for the Propagation of the Gospel. Nov. 1 to Dec. 31, 1868 and April 1 to June 30th, 1869, Vol. E26a, pp.833-849 and pp. 851 – 859, Rhodes House Library, Oxford.

Wilson, Captain. 1866. Report on the Indian Tribes Inhabiting the Country in the Vicinity of the Forty-Ninth Parallel of North Latitude. Transactions of the Ethnological Society of London, New Series 4:275-332, London.

Wood, James. 1851. Description of Juan de Fuca Strait. The Nautical Magazine and Naval Chronicle. A Journal of Papers on Subjects Connected with Maritime Affairs, January, London.